Abstract

Objectives

To identify predictive factors of radiological progression in early arthritis patients treated by remission-steered treatment.

Methods

In the IMPROVED study, 610 patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or undifferentiated arthritis (UA) were treated with methotrexate (MTX) and a tapered high dose of prednisone. Patients in early remission (disease activity score (DAS) <1.6 after 4 months) tapered prednisone to zero. Patients not in early remission were randomised to arm 1: MTX plus hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine and prednisone, or to arm 2: MTX plus adalimumab. Predictors of radiological progression (≥0.5 Sharp/van der Heijde score; SHS) after 2 years were assessed using logistic regression analysis.

Results

Median (IQR) SHS progression in 488 patients was 0 (0–0) point, without differences between RA or UA patients or between treatment arms. In only 50/488 patients, the SHS progression was ≥0.5: 33 (66%) were in the early DAS remission group, 9 (18%) in arm 1, 5 (10%) in arm 2, 3 (6%) in the outside of protocol group. Age (OR (95% CI): 1.03 (1.00 to 1.06)) and the combined presence of anticarbamylated protein antibodies (anti-CarP) and anticitrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) (2.54 (1.16 to 5.58)) were independent predictors for SHS progression. Symptom duration <12 weeks showed a trend.

Conclusions

After 2 years of remission steered treatment in early arthritis patients, there was limited SHS progression in only a small group of patients. Numerically, patients who had achieved early DAS remission had more SHS progression than other patients. Positivity for both anti-CarP and ACPA and age were independently associated with SHS progression.

Trial registration numbers

ISRCTN Register number 11916566 and EudraCT number 2006 06186-16.

Keywords: Ant-CCP, Early Rheumatoid Arthritis, Treatment, Autoantibodies

Key messages.

Earlier treatment with combination therapy and a treat-to-target approach have resulted in earlier and better suppression of inflammation, and radiological progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Induction therapy followed by remission-steered treatment results in less Sharp/van der Heijde score (SHS) progression in rheumatoid arthritis and undifferentiated arthritis.

Age is associated with minimal SHS progression, which may represent primary hand osteoarthritis with increasing age causing joint space narrowing.

Combination of anticarbamylated protein antibodies and anticitrullinated protein antibodies positivity is also associated with minimal SHS progression, which represents a phenotype with particularly bad prognosis.

Identifying predictive factors of minimal SHS progression may be relevant for understanding RA phenotypes; however, it is unlikely that limited SHS progression will become clinically relevant in the intermediate future.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) treatment has considerably changed in the past decades. Earlier treatment with combination therapy and a treat-to-target approach have resulted in earlier and better suppression of inflammation and radiological progression.1–7 It is thought that induction of disease activity score (DAS) remission, for which even stricter criteria are defined, will ensure optimal suppression of disease processes.8 With joint destruction becoming a rare outcome, this is mainly of pathophysiological interest, which patients remain most at risk for radiological progression.

Anticitrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) positivity in RA is associated with more radiological joint damage; in undifferentiated arthritis (UA) and arthralgia it predicts progression to RA.9 10 Also, the recently identified anticarbamylated protein antibodies (anti-CarP) are associated with more radiological progression, specifically in ACPA-negative patients.9 The presence of anti-CarP predates clinical disease;11–13 in arthralgia patients it can predict the progression to RA regardless of ACPA status.10

In addition, previous research showed that loss of bone mineral density, as measured with Digital X-ray Radiogrammetry (DXR-BMD) in the metacarpals using standard hand radiographs, in the first 4 months is associated with radiological progression after 1 year.14 Local BMD loss occurs early in the disease course and may be caused by increased osteoclast activity caused by inflammation processes.

In the IMPROVED study, we treated patients with early RA and UA with the aim to induce and maintain clinical remission (DAS<1.6). DAS remission rates were high, and radiological progression low.7 15 Yet, some patients still developed radiological progression, and this provides an opportunity to look for factors associated with and potentially driving radiological progression. Thus, in this post hoc analysis we aimed to determine which baseline characteristics and 4-month outcomes are associated with joint damage after 2 years of remission-steered treatment.

Methods

Subjects and study design

The IMPROVED study is a multicentre, randomised clinical trial with 610 patients ≥18 years having symptom duration ≤2 years, and not treated with previous antirheumatic therapy, diagnosed with early RA (2010 classification criteria16) or UA, defined by at least one inflammatory arthritis and one other painful joint, clinically suspected for early RA according to the treating rheumatologist. Medical Ethics Committees of all participating centres approved the study protocol and all patients gave written informed consent.

All patients started treatment with methotrexate (MTX) 25 mg/week and prednisone tapered from 60 mg/day to 7.5 mg/day in 7 weeks. After 4 months, patients who achieved a DAS<1.6 (early DAS remission) tapered prednisone to 0. If remission was maintained at 8 months, MTX was tapered to 0. Patients who were not in early DAS remission after 4 months were randomised to arm 1: MTX, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), sulfasalazine (SSZ) and prednisone, or to arm 2: MTX+adalimumab. If patients in arm 1 were in remission after 8 months, first prednisone, then SSZ and finally HCQ were tapered to 0. Four months later, MTX could be tapered to 0 if patients achieved remission. In arm 2, after 8 months, adalimumab was tapered to 0 if patients achieved remission and if the remission was maintained 4 months later, MTX was tapered to 0. Treatment adjustments were made every 4 months; medication was tapered and finally stopped in case of remission, but increased or switched in case of no remission. Fifty patients who did not achieve early DAS remission were not randomised as the protocol required; they were treated outside of protocol (OP) according to their rheumatologist based on the DAS. Details about the study protocol were previously published.7 We used data from 488 patients who had full sets of radiographs of hands and feet at baseline and after 2 years. For the other patients either a baseline or 2-year radiograph was missing.

Measurements

Radiological damage was assessed from radiographs of hands and feet annually in random order using the Sharp/van der Heijde score (SHS) as the mean of two independent readers, blinded for patient identity.17 Radiological progression was defined as an increase in SHS≥0.5 point. Since only a small group of patients (50/488) showed progression, reliability could not be measured by intraclass coefficients.18 Consensus scores were reached for radiographs with inter-reader difference of ≥2 points progression. Suitable routine digital X-rays of both hands were used to measure DXR-BMD by DXR online (Sectra, Linköping, Sweden)19 at baseline and 4 months. ‘DXR-BMD loss’ was defined as a loss in DXR-BMD of ≥1.5 mg/cm2/4 months calculated by subtracting DXR-BMD at 4 months with DXR-BMD at baseline.14

Anti-CarP were measured in sera at baseline by ELISA using carbamylated FCS in-house as described before.9 ACPA were determined at baseline using the anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP2) test.

‘Boolean remission’ was defined by the 2011 American College of Rheumatology European League Against Rheumatism (ACR/EULAR) remission criteria8 and was measured after 4 months.

Statistical analysis

For the analysis of continuous data we used the independent t test and for categorical data, the χ2 test. Mann-Whitney test and χ2 test were used for non-Gaussian data.

Clinical and radiological predictors at baseline and 4-month outcomes were put into the univariable logistic regression analysis with SHS progression as binary outcome. Variables with a p value <0.2 were entered into the multivariable model.

Early DXR-BMD loss showed a p value <0.2; however, this was a variable with almost half of the missing values due to unsuitability of the X-rays to measure the DXR-BMD. In order to avoid bias and to increase power, the variable was imputed using multiple imputation in 442 patients who had at least one DXR-BMD measure.

Anti-CarP and ACPA could not be entered into the same model due to multicollinearity. Therefore, a combined variable was entered into the model. Data was analysed by the statistical program SPSS V.20.0.

Results

Clinical characteristics and treatment

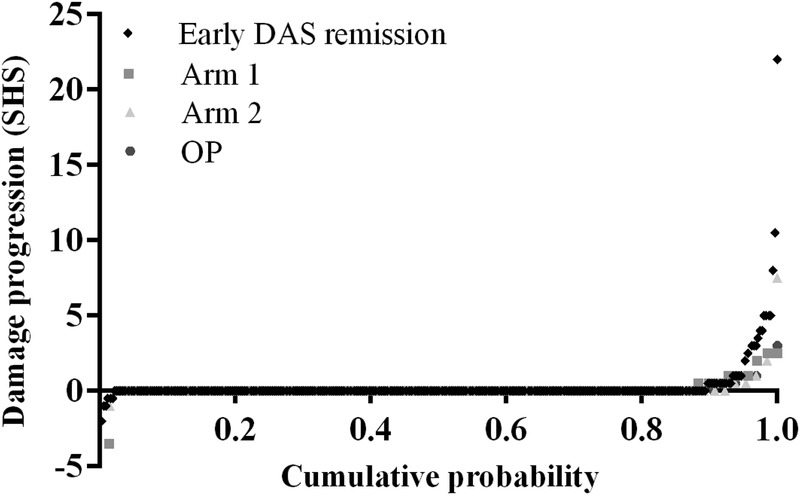

After 2 years, median SHS progression in all groups (early DAS remission, arm 1, arm 2, and OP) and in patients with RA and UA was 0 (range 0–22). Fifty of 488 patients (10%) had SHS progression: 33/387 (9%) in early DAS remission, 9/83 (11%) in arm 1, 5/78 (6%) in arm 2, 3/50 (6%) in the OP group (table 1 and figure 1). JSN progression was seen in 23/33 patients in early DAS remission, 9/9 in arm 1, 4/5 in arm 2, and 2/3 in the OP group. Erosion progression was scored in 17/33 patients in early DAS remission, 0 in arm 1, 2 in arm 2, and 1 in the OP group. Eight of 50 (16%) patients (all RA, 7 in early DAS remission and 1 in arm 2) had ≥5 SHS progression (minimal clinically important difference and smallest detectable difference20) (see online supplementary table S1). Twenty-two of 50 (44%) patients (20 patients with RA and 2 patients with UA, 16 in early DAS remission, 3 in arm 1, 2 in arm 2, and 1 in OP group) had ≥2 SHS progression (smallest detectable change21). Ten of 33 early DAS remission patients with SHS progression were in drug-free remission (DFR) after 2 years. One of 33 patients had ≥5 SHS progression (see online supplementary table S1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes for the total population, SHS progression and no SHS progression

| Total population n=488 | SHS progression n=50 | No SHS progressionn=438 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| Age (years), mean±SD | 51±14 | 56±12 | 51±14 | 0.008 |

| Female, n (%) | 333 (68) | 33 (66) | 300 (68) | 0.720 |

| RA (2010), n (%) | 388 (80) | 41 (82) | 347 (79) | 0.777 |

| DAS, mean±SD | 3.19±0.91 | 3.25±1.08 | 3.19±0.89 | 0.649 |

| HAQ, mean±SD | 1.15±0.67 | 1.09±0.66 | 1.15±0.67 | 0.545 |

| Symptom duration (in weeks), median (IQR) | 18 (9–34) | 25 (16–39) | 17 (9–32) | 0.032 |

| RF positive, n (%) | 273 (56) | 31 (62) | 242 (55) | 0.242 |

| ACPA positive, n (%) | 274 (56) | 35 (70) | 239 (55) | 0.053 |

| Anti-CarP positive,n (%) | 139 (29) | 22 (44) | 117 (27) | 0.012 |

| ESR mm/h(median, IQR) | 24 (11–39) | 31 (19.5–43.5) | 24 (10.8–38.0) | 0.020 |

| SJC, median (IQR) | 5 (3–10) | 5 (2–12) | 5 (3–10) | 0.921 |

| TJC, median (IQR) | 6 (4–10) | 5 (4–9) | 6 (4–10) | 0.263 |

| SHS, median (IQR) | 0 (0–0) | 1.25 (0–4) | 0 (0–0) | <0.001 |

| DXR-BMD* g/cm2, median (IQR) | 0.591 (0.527–0.643) | 0.582 (0.479–0.632) | 0.593 (0.529–0.642) | 0.322 |

| 4 months | ||||

| DAS, mean±SD | 1.49±0.88 | 1.43±0.93 | 1.49±0.87 | 0.607 |

| ACR/EULAR remission, n (%) | 125 (26) | 16 (32) | 109 (25) | 0.264 |

| Early DAS remission, n (%) | 322 (66) | 33 (66) | 289 (66) | 0.998 |

| Arm 1 DMARD combination, n (%) | 69 (14) | 9 (18) | 60 (14) | 0.408 |

| Arm 2 adalimumab,n (%) | 65 (13) | 5 (10) | 60 (14) | 0.466 |

| Outside of Protocol,n (%) | 32 (7) | 3 (6) | 29 (7) | 0.867 |

| DXR-BMD* g/cm2, median (IQR) | 0.588 (0.522–0.631) | 0.579 (0.496–0.646) | 0.590 (0.522–0.631) | 0.747 |

| 2 years | ||||

| DAS, mean±SD | 1.47±0.83 | 1.52±0.85 | 1.47±0.83 | 0.670 |

| HAQ, mean±SD | 0.54±0.60 | 0.58±0.62 | 0.53±0.60 | 0.583 |

| Total SHS, median (IQR) | 0 (0–0.5) | 4 (1.0–6.6) | 0 (0–0) | <0.001 |

| SHS progression, median (IQR) | 0 (0–0) | 1 (0.5–3.0) | 0 (0–0) | <0.001 |

| JSN, n (%) | 111 (23) | 40 (80) | 71 (16) | <0.001 |

| JSN, median (IQR) | 0 (0–0) | 3 (0.9–6.0) | 0 (0–0) | <0.001 |

| JSN progression, n (%) | 38 (78) | 37 (74) | 1 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| JSN progression,median (IQR) | 1.8 (0.9–3.0) | 1.5 (0.8–3.0) | 2 (2–2) | <0.001 |

| Erosive, n (%) | 49 (10) | 26 (52) | 23 (5) | <0.001 |

| Erosion score,median (IQR) | 0 (0–0) | 0.5 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) | <0.001 |

| Erosion progression, n (%) | 20 (41) | 20 (40) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Erosion progression, median (IQR) | 0.5 (0.5–3.0) | 0.5 (0.5–3.0) | 0 (0–0) | <0.001 |

| DAS-remission, n (%) | 285 (58) | 29 (58) | 256 (58) | 0.905 |

| Drug-free remission,n (%) | 123 (25) | 12 (24) | 111 (25) | 0.822 |

*DXR-BMD data imputed in 442 patients.

ACPA, anticitrullinated protein antibodies; anti-CarP, anticarbamylated protein antibodies; ACR, American College of Rheumatology; DAS, disease activity score; DXR-BMD, metacarpal bone mineral density measured by digital X-ray radiogrammetry; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; HAQ, health assessment questionnaire; JSN, joint space narrowing; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RF, rheumatoid factor; SHS, Sharp/van der Heijde score; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count.

Figure 1.

Probability plot of SHS progression over 2 years for the different treatment groups (uploaded as a separate file: figure 1). DAS, disease activity score; OP: outside of protocol group; SHS: Sharp/van der Heijde score.

Treatment steps during 2 years of follow up in patients with SHS progression n=50

rmdopen-2015-000172supp_table.pdf (92.2KB, pdf)

After 4 months, 144 patients (all in early DAS remission) were in ‘Boolean remission’. Mean (SD) age in ‘Boolean remission’ patients was 51.2 (14.3) years, and 51.8 (13.9) years for patients not in ‘Boolean remission’, p=0.662 (table 2). ACPA positivity (86 (60%) vs 223 (53%), p=0.106) and anti-CarP positivity (47 (33%) vs 116 (28%), p=0.166) were similar in both groups. SHS progression was seen in 16/144 (11%) of ‘Boolean remission’ patients and 31/420 (7%) patients not in ‘Boolean remission’ (p=0.264). The other three patients who had SHS progression had missing data to calculate ‘Boolean remission’. Median (IQR) SHS progression was not different in patients in ‘Boolean remission’ 0 (0–0), and patients not in ‘Boolean remission’ 0 (0–0), p=0.357.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes according to ‘Boolean remission’ measured after 4 months

| ‘Boolean remission’ n=144 |

No ‘Boolean remission’ n=420 |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| Age (years), mean±SD | 51.2±14.3 | 51.8±13.9 | 0.662 |

| Female, n (%) | 89 (62) | 290 (69) | 0.110 |

| RA (2010), n (%) | 114 (79) | 327 (78) | 0.707 |

| DAS, mean±SD | 3.05±0.91 | 3.28±0.92 | 0.008 |

| HAQ, mean±SD | 1.04±0.67 | 1.21±0.65 | 0.007 |

| Symptom duration (in weeks), median (IQR) | 17 (8.8–34) | 17.5 (9–32) | 0.784 |

| RF positive, n (%) | 88 (61) | 228 (54) | 0.139 |

| ACPA positive, n (%) | 86 (60) | 223 (53) | 0.106 |

| Anti-CarP, n (%) | 47 (33) | 116 (28) | 0.166 |

| ESR mm/h, median (IQR) | 26.5 (11.5–36.8) | 24 (11–41) | 0.596 |

| SJC, median (IQR) | 5 (2.3–10) | 6 (3–10) | 0.796 |

| TJC, median (IQR) | 5 (4–8) | 7 (4–11) | <0.001 |

| Total SHS, median (IQR) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0.714 |

| Early DAS remission 4 months, n (%) | 144 (100) | 226 (54) | <0.001 |

| Arm 1, n (%) | 0 (0) | 77 (18) | <0.001 |

| Arm 2, n (%) | 0 (0) | 71 (17) | <0.001 |

| OP (%) | 0 (0) | 46 (11) | <0.001 |

| 2 years | |||

| DAS, mean±SD | 1.11±0.75 | 1.61±0.83 | <0.001 |

| HAQ, mean±SD | 0.29±0.44 | 0.64±0.61 | <0.001 |

| Total SHS, median (IQR) | 0 (0–0.5) | 0 (0–0.5) | 0.939 |

| SHS progression, median (IQR) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0.357 |

| SHS progression, n (%) | 16 (11) | 31 (7) | 0.264 |

| DAS remission, n (%) | 103 (72) | 186 (44) | <0.001 |

| Drug-free remission, n (%) | 51 (35) | 72 (17) | <0.001 |

| ACR/EULAR remission, n (%) | 67 (47) | 63 (15) | <0.001 |

ACPA, anticitrullinated protein antibodies; Anti-CarP, anticarbamylated protein antibodies; ACR, American College of Rheumatology; DAS, disease activity score; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; HAQ, health assessment questionnaire; OP, out of protocol group; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RF, rheumatoid factor; SHS, Sharp/van der Heijde score; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count.

SHS progression

Median (IQR) SHS progression in patients with SHS progression was 1.0 (0.5–3.0); joint space narrowing (JSN) progression 1.5 (0.8–3.0), and erosion progression 0.5 (0.0–1.0). Thirty-eight of 488 patients (30 RA and 8 UA, p=0.831) had JSN progression and 20/488 (19 RA and 1 UA, p=0.145) had erosion progression. Patients with SHS progression were older (5/50 patients with SHS progression were <45 years vs 122/438 patients without SHS progression were <45 years, p=0.035), had a longer symptom duration (11/50 symptom duration <12 weeks vs 146/438, p=0.092, respectively), were more often anti-CarP-positive (p=0.012) and numerically also more often ACPA-positive or RF-positive, and had a higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (31/50 ESR >28 mm/hr vs 183/438, p=0.006, respectively) (table 1).

Anti-CarP

One hundred thirty-nine of 488 patients (28%) were anti-CarP-positive; 274/488 (56%) were ACPA-positive; 273/488 (56%) were RF-positive; 122/488 (25%) were double positive for anti-CarP and ACPA; and 107/488 (22%) were positive for all three. Double positivity occurred more in patients with RA than in patients with UA (table 3). In anti-CarP-positive patients there was no difference between ACPA-positive and ACPA-negative patients in SHS progression (median (IQR) 0 (0–0) vs 0 (0–0), p=0.354). Median (IQR) SHS at baseline and 2 years was comparable between anti-CarP-positive and anti-CarP-negative patients (table 3). Besides, median SHS at baseline was comparable between double positive (0 (0–1)) and ACPA-positive but anti-CarP-negative patients (0 (0–2), p=0.088) and also at 2 years this was comparable 0 (0–0) vs 0 (0–0.5), p=0.073.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes according to anti-CarP status

| Anti-CarP-positive n=172 | Anti-CarP-negative n=350 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| Age (years), mean±SD | 52±13 | 52±15 | 0.570 |

| Female, n (%) | 116 (67) | 238 (68) | 0.898 |

| RA (2010), n (%) | 162 (94) | 254 (73) | <0.001 |

| DAS, mean±SD | 3.27±0.91 | 3.22±0.94 | 0.624 |

| HAQ, mean±SD | 1.12±0.66 | 1.19±0.65 | 0.292 |

| Symptom duration (in weeks), median (IQR) | 17 (8–33) | 18 (9–33) | 0.517 |

| Symptom duration <12 weeks, n (%) | 64 (37) | 113 (32) | 0.262 |

| RF positive, n (%) | 143 (83) | 147 (42) | <0.001 |

| ACPA positive, n (%) | 150 (87) | 134 (38) | <0.001 |

| ESR mm/h, median (IQR) | 31 (17–44.8) | 21 (10–38) | 0.001 |

| SJC, median (IQR) | 6 (3–9) | 5 (3–10) | 0.714 |

| TJC, median (IQR) | 6 (4–9) | 7 (4–10) | 0.540 |

| Total SHS, median | 0 (0–0.5) | 0 (0–0) | 0.361 |

| Early DAS remission 4 months, n (%) | 116 (67) | 203 (58) | 0.038 |

| 2 years | |||

| DAS, mean±SD | 1.46±0.87 | 1.51±0.82 | 0.536 |

| HAQ, mean±SD | 0.46±0.57 | 0.58±0.61 | 0.064 |

| Total SHS, median (IQR) | 0 (0–1.4) | 0 (0–0.5) | 0.179 |

| SHS progression, median (IQR) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0.025 |

| SHS progression, n (%)* | 22 (13) | 22 (6) | 0.012 |

| DAS remission, n (%) | 88 (51) | 170 (49) | 0.648 |

| Drug-free remission, n (%) | 32 (19) | 84 (24) | 0.111 |

| ACR/EULAR remission, n (%) | 42 (24) | 75 (21) | 0.489 |

ACPA, anticitrullinated protein antibodies; Anti-CarP, anticarbamylated protein antibodies; ACR, American College of Rheumatology; DAS, disease activity score; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; HAQ, health assessment questionnaire; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RF, rheumatoid factor; SHS, Sharp/van der Heijde score; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count.

*The other 6 patients with SHS progression had missing anti-CarP values.

Predictors of SHS progression

Univariable predictors for SHS progression after 2 years that were entered into the multivariable model showed double positivity for anti-CarP and ACPA (p=0.011), anti-CarP alone (p=0.014) (ACPA alone showed a trend (p=0.056)), age (p=0.009), baseline ESR>28 mm (p=0.007), baseline SHS (p=0.041) and symptom duration <12 weeks (showed a trend p=0.096; table 4). Early DXR-BMD loss was associated with SHS progression (p=0.019); however, the imputed variable was not associated (p=0.100) and therefore, not entered in the model. Only age (OR (95% CI): 1.03 (1.00 to 1.06)) and the combination of anti-CarP and ACPA positivity (2.54 (1.16 to 5.58)) were independent significant predictors (table 4). Symptom duration <12 weeks (0.49 (0.23 to 1.04)), ESR>28 mm (1.90 (0.95 to 3.81)), and SHS (1.04 (0.98 to 1.11)) were not significantly associated, but were entered in the model because of a probable association with SHS progression.

Table 4.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis with SHS progression as binomial outcome variable

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable analysis | |||

| Age | 1.03 | 1.01 to 1.06 | 0.009 |

| Female | 0.89 | 0.48 to 1.66 | 0.720 |

| RA | 1.12 | 0.52 to 2.39 | 0.777 |

| DAS | 1.08 | 0.79 to 1.48 | 0.648 |

| Symptom duration <12 weeks | 0.55 | 0.28 to 1.11 | 0.096 |

| RF | 1.46 | 0.77 to 2.75 | 0.244 |

| Anti-CarP/ACPA | |||

| Both negative | ref | ||

| Anti-CarP−ACPA+ | 1.27 | 0.53 to 3.05 | 0.592 |

| Anti-CarP+ACPA−* | 0.86 | 0.10 to 7.04 | 0.885 |

| Both positive | 2.67 | 1.26 to 5.66 | 0.011 |

| CRP | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 0.646 |

| ESR >28 mm | 2.27 | 1.25 to 4.15 | 0.007 |

| SJC | 1.02 | 0.98 to 1.07 | 0.338 |

| TJC | 0.99 | 0.93 to 1.05 | 0.661 |

| DAS remission 4 months | 0.97 | 0.53 to 1.79 | 0.932 |

| Arm 1† | 1.80 | 0.57 to 5.69 | 0.317 |

| Arm 2‡ | 0.56 | 0.18 to 1.76 | 0.317 |

| Early ACR/EULAR remission | 1.44 | 0.76 to 2.74 | 0.266 |

| SHS | 1.10 | 1.00 to 1.20 | 0.041 |

| Erosion score | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.02 | 0.812 |

| JSN score | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.804 |

| Early DXR-BMD loss | 1.22 | 1.03 to 1.45 | 0.019 |

| Early DXR-BMC loss, imputed§ | 1.18 | 0.97 to 1.45 | 0.100 |

| Multivariable analysis | |||

| Age | 1.03 | 1.00 to 1.06 | 0.049 |

| Anti-CarP/ACPA | |||

| Both negative | ref | ||

| Anti-CarP−ACPA + | 1.41 | 0.57 to 3.46 | 0.457 |

| Anti-CarP+ACPA−* | 1.13 | 0.13 to 9.68 | 0.908 |

| Both positive | 2.54 | 1.16 to 5.58 | 0.020 |

| Symptom duration <12 weeks | 0.49 | 0.23 to 1.04 | 0.063 |

| ESR >28 mm | 1.90 | 0.95 to 3.81 | 0.070 |

| SHS | 1.04 | 0.98 to 1.11 | 0.208 |

*n=16 patients.

†Reference category arm 2.

‡Reference category arm 1.

§DXR-BMD data imputed in 442 patients.

ACPA, anticitrullinated protein antibodies; Anti-CarP, anticarbamylated protein antibodies; ACR, American College of Rheumatology; CRP, C reactive protein; DAS, disease activity score; DXR-BMD, metacarpal bone mineral density measured by digital X-ray radiogrammetry; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; JSN, joint space narrowing; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RF, rheumatoid factor; SHS, Sharp/van der Heijde score; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count; Wks, weeks.

An additional multivariable model including only ACPA and not anti-CarP showed that symptom duration, age and ESR were independent significant predictors (data not shown). A model with anti-CarP instead showed that only anti-CarP was the independent predictor (data not shown). The model with ACPA was a stronger predictor with a R2 of 0.053 compared to 0.047 for the model with anti-CarP.

Discussion

Of 488 early patients with arthritis who were treated with induction therapy followed by remission-steered treatment, only 50/488 (10%) patients showed SHS progression ≥0.5 after 2 years and only 8 patients showed SHS progression ≥5 which is considered to be the minimal clinically important difference in SHS. We looked at potential predictors of radiological progression (after 2 years of treatment) in these patients where disease activity was generally low, and radiological progression was generally effectively suppressed as this allowed us to look for factors associated with radiological progression unconnected to (suppression of) inflammation. This may be relevant for understanding RA phenotypes. It is unlikely that limited SHS progression will become clinically relevant for these patients in the intermediate future.

To determine why this group still shows SHS progression, we investigated associations between baseline characteristics and 4-month outcomes with SHS progression. We found that SHS progression comprised more of progression of JSN than of progression of erosions. Small numbers prevented us from analysing both forms of progression separately. Independent predictors for total SHS progression were higher age and the combination of anti-CarP and ACPA positivity. In a reverse of an association between higher disease activity and more damage progression, we found more SHS progression in patients who had achieved early (4 months after treatment start) DAS remission, or even early ‘Boolean remission’. Although these patients even after drug tapering as required by protocol on average have lower DAS than patients who did not achieve early remission and for whom medication was intensified, it may be possible that there was residual inflammation which triggered the SHS progression. Discontinuation of prednisone may also have removed a drug which even without influencing the DAS may prevent damage progression.22 As online supplementary table S1 suggests, discrepancies in clinical response and radiological damage progression may indicate that in some patients antirheumatic treatment may effectively suppress symptoms of inflammation, while the underlying processes driving joint destruction may still be present.

Although for most patients treated for DAS remission the SHS progression may be a clinically irrelevant finding, for some patients initial SHS progression will still result in later permanent disability23 that will require tailored treatment decisions. In addition, identifying risk factors for SHS progression in this population may point towards underlying mechanisms and possibly to new drug targets.

Small numbers limited our choice of analyses and interpretation of results. Since both ACPA and anti-CarP have been shown to be related with SHS progression in other RA cohorts, it is likely that this combination of risk factors indicate a RA phenotype with a bad prognosis for joint damage. As there were few patients with anti-CarP but with negative ACPA, we could not test which of the antibodies was the stronger predictor. However, it appears that in this early and progressively treated patient group, presence of ACPA is a risk factor for SHS progression only if anti-CarP was also present. Although data in animal studies suggested a direct effect of human ACPA on osteoclastogenesis, several questions remain open regarding the biochemical nature of ACPA and the specificities involved.24 The effects of anti-CarP in joint destruction on such a mechanistic level is currently unknown, but epidemiological studies show a clear association between anti-CarP and joint destruction, especially in the ACPA-negative patients.9 11 Also with regard to double positivity of anti-CarP and ACPA, the diagnostic value was clear with high OR for RA. As ACPA and anti-CarP can bind to different antigens,13 it is possible that especially the combined presence is sufficient to drive bone destruction. However, even though mice can harbour anti-CarP antibodies,25 experimental evidence to indicate a pathological role for anti-CarP is still lacking.

We found age to be a predictor of SHS progression. As we found that SHS progression was dominated by JSN progression rather than erosion progression in these patients, some JSN progression may represent primary hand osteoarthritis. This has been also previously suggested in a study by Khanna et al.26

Short symptom duration showed a trend as a protective factor; however, possibly due to small numbers, this was not statistically significant. It is also possible that the intensive remission steered treatment in all patients obscured potential advantages of early treatment start. Previous research indicates that shorter symptom duration in RA is associated with less SHS progression.27 28 SHS progression occurred numerically more often in patients with RA than in patients with UA. This corroborates the FINRA-Co and NEORA-Co findings that included not UA but only patients with RA, who despite remission-steered treatment showed more SHS progression than the IMPROVED patients. It may also reflect that classification as RA according to the 2010 classification criteria, used in our study, can rest strongly on the presence of ACPA.

It was not possible to calculate progression in 122 patients due to missing radiographs at baseline or at 2 years. Of these 122 patients, 79 were lost to follow-up and 43 patients had missing radiographs while they were in the study. We could not detect systematic errors concerning these missing radiographs and therefore, consider that we have analysed a considerable part of the data.

A threshold for SHS progression of 0.5 seems clinically irrelevant. The majority of our patients had ‘zero progression’. Only a small group had progression within a small range. This damage progression is at least pathophysiologically of interest. JSN that is scored may represent OA mechanisms in our patients; this was also found as a result of our regression analysis.

Finally, SHS progression appeared slightly higher in patients who had achieved early DAS remission. By protocol, patients were required to taper and eventually discontinue all disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) when DAS remission was achieved, but had to restart as soon as DAS remission was lost. Previously, we found no radiological damage progression in patients with RA who had drug-free remission in the BeSt study, regardless of whether drug free remission was lost or not.29 Compared to the IMPROVED patients, however, BeSt patients had tapered medication over a long period of low disease activity and subsequent remission before the last DMARD was stopped. In the current study, initiated in 2007, tapering and drug discontinuation was carried out more quickly as we also included patients with UA, some of whom could have had a self-limiting, non-damaging type of arthritis. It is possible that if DMARDs are discontinued too quickly the RA disease activity is not sufficiently suppressed, allowing SHS progression in some patients. Studies involving imaging techniques in patients who are in clinical remission also suggest that residual inflammation may be present, which can be associated with subsequent damage progression.30–32 In our study we did not perform additional imaging to detect this residual subclinical disease. The 2010 EULAR recommendations advise to taper DMARDs slowly only in patients with stable remission and discontinuation of DMARDs is not encouraged, although it is considered to be an option in some patients. However, we found that DFR was achieved in similar percentages of patients who had achieved early DAS remission with or without SHS progression. To continue treatment when patients are in DAS remission might prevent further SHS progression; however, without clear clinical benefits this probably would entail overtreatment with unnecessary (risks of) side effects.

In conclusion, after 2 years of remission-steered treatment in early arthritis patients who started induction therapy, minimal SHS progression occurs in a small group of patients. Independent predictors for SHS progression were age (associated with JSN possibly related to osteoarthritis), and the combination of anti-CarP and ACPA positivity, which appears to represent a phenotype with particularly bad prognosis even when suppression of inflammatory activity by remission-steered treatment prevents damage in other patients. Further research may show whether previous associations of presence of ACPA with bad outcomes of arthritis rests with mechanisms related to ACPA itself, presence of both ACPA and anti-CarP, or mainly with anti-CarP.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all patients as well as the following rheumatologists (other than the authors) who participated in the IMPROVED study group (all locations are in the Netherlands): WM de Beus (Medical Center Haaglanden, Leidschendam); MHW de Bois (Medical Center Haaglanden, The Hague); M de Buck (Medical Center Haaglanden, Leidschendam); G Collée (Medical Center Haaglanden, The Hague); JAPM Ewals (Haga Hospital, The Hague); RJ Goekoop (Haga Hospital, The Hague); BAM Grillet (Zorgsaam Hospital, Terneuzen); JHLM van Groenendael (Franciscus Hospital, Roosendaal); AL Huidekoper (Bronovo Hospital, The Hague); SM van der Kooij (Haga Hospital, The Hague); ETH Molenaar (Groene Hart Hospital, Gouda); AJ Peeters (Reinier de Graaf Gasthuis, Delft); N Riyazi (Haga hospital, The Hague); HK Ronday (Haga hospital, The Hague); AA Schouffoer (Haga Hospital, The Hague); PBJ de Sonnaville (Admiraal de Ruyter Hospital, Goes); I Speyer (Bronovo Hospital, The Hague); the authors would also like to thank all other rheumatologists and trainee rheumatologists who enrolled patients in this study, and all research nurses for their contributions.

Footnotes

Contributors: GA performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. MKV, LH, KVCW-dB, YPMG-R, MvO, JBH, CB, GMS-B, LRL and LAT contributed to the acquisition of data and revision of the manuscript. TH participated in the study design, contributed to the acquisition of data and was involved in revising the manuscript. CFA participated in the study design, contributed to the acquisition of data, and was involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was financially supported by AbbVie in the first year of the IMPROVED study. Study design, trial management, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and preparation of the manuscript were performed by the authors without input from the sponsor. The work of Dr Trouw was supported by a ZON-MW Vidi grant and a fellowship from Janssen-biologicals.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The medical ethics committees of all participating centres approved the study protocol and all patients gave written informed consent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: GA had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The data is from a full database of the IMPROVED study. Additional unpublished data are not available.

References

- 1.Egsmose C, Lund B, Borg G et al. . Patients with rheumatoid arthritis benefit from early 2nd line therapy: 5 year followup of a prospective double blind placebo controlled study. J Rheumatol 1995;22:2208–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finckh A, Liang MH, van Herckenrode CM et al. . Long-term impact of early treatment on radiographic progression in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2006;55:864–72. 10.1002/art.22353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF et al. . Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3381–90. 10.1002/art.21405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mottonen T, Hannonen P, Leirisalo-Repo M et al. . Comparison of combination therapy with single-drug therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised trial. FIN-RACo trial group. Lancet 1999;353:1568–73. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)08513-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Heide A, Jacobs JW, Bijlsma JW et al. . The effectiveness of early treatment with “second-line” antirheumatic drugs. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:699–707. 10.7326/0003-4819-124-8-199604150-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Dongen H, van Aken J, Lard LR et al. . Efficacy of methotrexate treatment in patients with probable rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:1424–32. 10.1002/art.22525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wevers-de Boer KVC, Visser K, Heimans L et al. . Remission induction therapy with methotrexate and prednisone in patients with early rheumatoid and undifferentiated arthritis (the IMPROVED study). Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1472–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G et al. . American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:573–86. 10.1002/art.30129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi J, Knevel R, Suwannalai P et al. . Autoantibodies recognizing carbamylated proteins are present in sera of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and predict joint damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108:17372–7. 10.1073/pnas.1114465108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi J, van de Stadt LA, Levarht EW et al. . Anti-carbamylated protein antibodies are present in arthralgia patients and predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:911–15. 10.1002/art.37830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brink M, Verheul MK, Ronnelid J et al. . Anti-carbamylated protein antibodies in the pre-symptomatic phase of rheumatoid arthritis, their relationship with multiple anti-citrulline peptide antibodies and association with radiological damage. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:25 10.1186/s13075-015-0536-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gan RW, Trouw LA, Shi J et al. . Anti-carbamylated protein antibodies are present prior to rheumatoid arthritis and are associated with its future diagnosis. J Rheumatol 2015;42:572–9. 10.3899/jrheum.140767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi J, van de Stadt LA, Levarht EW et al. . Anti-carbamylated protein (anti-CarP) antibodies precede the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:780–3. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wevers-de Boer KV, Heimans L, Visser K et al. . Four-month metacarpal bone mineral density loss predicts radiological joint damage progression after 1 year in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: exploratory analyses from the IMPROVED study. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:341–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heimans L, Wevers-de Boer KV, Visser K et al. . A two-step treatment strategy trial in patients with early arthritis aimed at achieving remission: the IMPROVED study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1356–61. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ III et al. . 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:2569–81. 10.1002/art.27584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Heijde D. How to read radiographs according to the Sharp/van der Heijde method. J Rheumatol 2000;27:261–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979;86:420–8. 10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosholm A, Hyldstrup L, Backsgaard L et al. . Estimation of bone mineral density by digital X-ray radiogrammetry: theoretical background and clinical testing. Osteoporos Int 2001;12:961–9. 10.1007/s001980170026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruynesteyn K, van der Heijde D, Boers M et al. . Determination of the minimal clinically important difference in rheumatoid arthritis joint damage of the Sharp/van der Heijde and Larsen/Scott scoring methods by clinical experts and comparison with the smallest detectable difference. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:913–20. 10.1002/art.10190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Navarro-Compan V, van der Heijde D, Ahmad HA et al. . Measurement error in the assessment of radiographic progression in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) clinical trials: the smallest detectable change (SDC) revisited. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1067–70. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boers M, van Tuyl L, van den Broek M et al. . Meta-analysis suggests that intensive non-biological combination therapy with step-down prednisolone (COBRA strategy) may also ‘disconnect’ disease activity and damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:406–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van den Broek M, Dirven L, de Vries-Bouwstra JK et al. . Rapid radiological progression in the first year of early rheumatoid arthritis is predictive of disability and joint damage progression during 8 years of follow-up. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1530–3. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harre U, Georgess D, Bang H et al. . Induction of osteoclastogenesis and bone loss by human autoantibodies against citrullinated vimentin. J Clin Invest 2012;122:1791–802. 10.1172/JCI60975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stoop JN, Liu BS, Shi J et al. . Antibodies specific for carbamylated proteins precede the onset of clinical symptoms in mice with collagen induced arthritis. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e102163 10.1371/journal.pone.0102163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khanna D, Ranganath VK, Fitzgerald J et al. . Increased radiographic damage scores at the onset of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis in older patients are associated with osteoarthritis of the hands, but not with more rapid progression of damage. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:2284–92. 10.1002/art.21221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Linden MP, le Cessie S, Raza K et al. . Long-term impact of delay in assessment of patients with early arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:3537–46. 10.1002/art.27692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Nies JA, Krabben A, Schoones JW et al. . What is the evidence for the presence of a therapeutic window of opportunity in rheumatoid arthritis? A systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:861–70. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klarenbeek NB, van der Kooij SM, Guler-Yuksel M et al. . Discontinuing treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in sustained clinical remission: exploratory analyses from the BeSt study. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:315–19. 10.1136/ard.2010.136556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gartner M, Alasti F, Supp G et al. . Persistence of subclinical sonographic joint activity in rheumatoid arthritis in sustained clinical remission. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:2050–3. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-207212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gent YY, Ter Wee MM, Voskuyl AE,et al. . Subclinical synovitis detected by macrophage PET, but not MRI, is related to short-term flare of clinical disease activity in early RA patients: an exploratory study. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:266 10.1186/s13075-015-0770-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tokai N, Ogasawara M, Gorai M et al. . Predictive value of bone destruction and duration of clinical remission for subclinical synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Mod Rheumatol 2015;25:540–5. 10.3109/14397595.2014.987421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Treatment steps during 2 years of follow up in patients with SHS progression n=50

rmdopen-2015-000172supp_table.pdf (92.2KB, pdf)