Abstract

Gun-related violence is a public health concern. This study synthesizes findings on associations between substance use and gun-related behaviors. Searches through PubMed, Embase, and PsycINFO located 66 studies published in English between 1992 and 2014. Most studies found a significant bivariate association between substance use and increased odds of gun-related behaviors. However, their association after adjustment was mixed, which could be attributed to a number of factors such as variations in definitions of substance use and gun activity, study design, sample demographics, and the specific covariates considered. Fewer studies identified a significant association between substance use and gun access/possession than other gun activities. The significant association between nonsubstance covariates (e.g., demographic covariates and other behavioral risk factors) and gun-related behaviors might have moderated the association between substance use and gun activities. Particularly, the strength of association between substance use and gun activities tended to reduce appreciably or to become nonsignificant after adjustment for mental disorders. Some studies indicated a positive association between the frequency of substance use and the odds of engaging in gun-related behaviors. Overall, the results suggest a need to consider substance use in research and prevention programs for gun-related violence.

Keywords: gun-related behaviors, mental disorders, substance use

INTRODUCTION

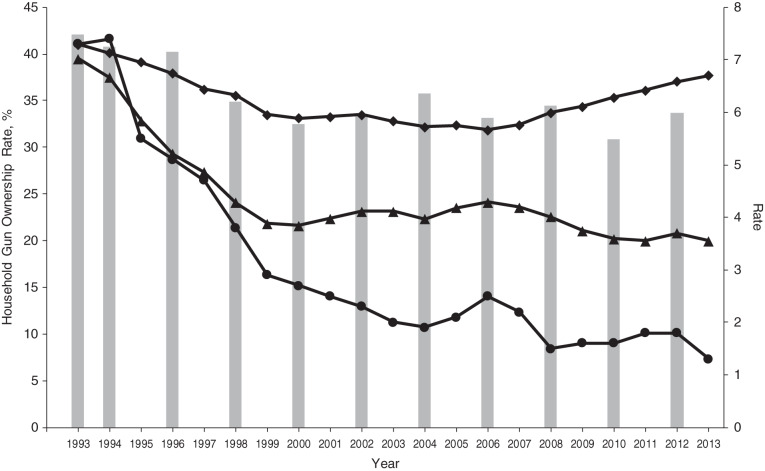

Prior studies suggest that the prevalence of gun-related violence is influenced by substance use behaviors (1, 2). In the past 2 decades, the decline of household firearm ownership rates paralleled the decrease in the rates of firearm homicides and nonfatal firearm victimizations in the United States (Figure 1) (3–7). The most marked decline occurred during the 1990s. The prevalence of household firearm ownership dropped about 10% from 42.67% in 1990 to 32.47% in 2000. The number of firearm homicides decreased from 18,253 (or 7 per 100,000 persons) in 1993 to 10,801 (or 3.8 per 100,000 persons) in 2000. During the 1990s, there was also a decline in firearm-related suicide rates. The number of nonfatal firearm victimizations in 2004 (456,500 or 1.9 per 1,000 persons aged ≥12 years) was less than one third of the number in 1993 (1.53 million or 7.3 per 1,000 persons aged ≥12 years). After the major decline, there were fluctuations in firearm ownership rates and firearm-related homicides and injuries during the 2000s and early 2010s, though they largely followed a downward trend. However, the death rates from firearm suicides have increased since 2006. In 2012, the household firearm ownership rate was about 33.72%. In 2013, nonfatal firearm victimizations, firearm suicides, and homicide deaths totaled 332,950 (or 1.3 per 1,000 persons aged ≥12 years), 21,175 (or 6.7 per 100,000 persons), and 11,208 (or 3.55 per 100,000 persons), respectively.

Figure 1.

Household firearm ownership rate and firearm violence in the United States, 1993–2013. Gray bars show household gun ownership rate; diamonds show firearm suicide deaths per 100,000 persons; triangles show firearm homicide deaths per 100,000 persons; and circles show nonfatal firearm victimizations per 1,000 persons aged ≥12 years. Data were compiled from different sources (3–7).

From a macro perspective, it was suggested that the decline of gun-related homicides in the 1990s was related to the changes in the crack cocaine market (8). During the mid to late 1980s, there was an increase in the demand for crack cocaine. Guns were acquired by drug dealers who used them for the protection of their lucrative businesses and diffused to other people who used them for self-protection in the larger community, potentially leading to escalated gun violence (8, 9). Conversely, the shrinking of the crack cocaine market might be one of the factors that was associated with the decline of gun violence in the 1990s (8). This hypothesis was consistent with a number of ecological studies using data for New York City (1, 2, 10). Specifically, it was found in these studies that cocaine consumption was positively associated with firearm-related homicide rates.

From a micro perspective, psychopharmacological effects of alcohol and drug use may induce or trigger violent behaviors. Compared with less violent forms of death such as poisoning, firearm use is a violent method (11). Acute and chronic alcohol consumption may suppress inhibitions, detect less threat, and produce violent impulses (12). It may impair subjects' executive functioning, leading to incorrect assessment of risks (12). Cocaine and crack cocaine use may trigger paranoid or psychotic symptoms when violence is likely to occur (13). Substance abusers are likely to be involved in more than one type of substances. One study found that, among people who committed suicide, 50% of cocaine users also tested positive for alcohol (14). The joint effects of multiple substances may increase the odds of violent behaviors.

The above explanations are consistent with Goldstein's (15) tripartite framework, which states that the link between substance use and gun violence may be psychopharmacological, economically compulsive (i.e., some drug users engage in crimes to get money for the costly drug), and systematic (i.e., violence arises inherently from the illegal drug market). The General Strain Theory posits that people may engage in deviant behaviors or crimes to alleviate negative emotions brought by stressful experiences (16). Building on the General Strain Theory, previous studies have found that either indirect (e.g., witnessing) or direct (e.g., victimization) exposure to violence is associated with an increased prevalence of substance use among adolescents (17, 18).

In addition to explanations based on a bidirectional causal relationship, the association between substance use and gun activities may also reflect clustering of multiple risk behaviors that may enhance the likelihood of engaging in the violent context (19–22). Previous studies have shown that the correlations among problem behaviors in adolescence and young adulthood may be explained by a common underlying factor, which is hypothesized to reflect “unconventionality in both the personality and the social environment” (23; 24, p. 763).

A growing number of studies have examined the association between various types of substance use/disorder and gun-related behaviors. Their findings, however, are mixed depending on the specific sample, analysis strategy, type of substance use/disorder defined, form of firearm-related outcomes used, and so on. For instance, 4 articles reported different conclusions, although all of them used the 2001–2003 National Comorbidity Survey Replication data set (25–28). Casiano et al. (26) showed that either alcohol abuse/dependence or drug abuse/dependence was associated with threatening others with a gun, after controlling for sociodemographic variables. Conversely, such an association was not significant, after adjustment for both demographics and other mental disorders (25, 26). When individual disorders were grouped into broad categories, any substance use disorder was associated with gun threats, even after adjustment for demographics and other disorder categories (26). Another 2 studies in general didn't find a significant association between alcohol/drug abuse/dependence and access to firearms in the home (27, 28).

Sample demographics such as sex, age, and racial composition may also contribute to mixed findings for the associations between substance use and gun activities. Results stratified by sex differed across studies. Anteghini et al. (29) found that drug use was associated with carrying a gun in the past month for both male and female adolescents. On the other hand, Callanan and Davis (30) didn't find a significant association between drug abuse and suicide by firearm either for men or women. Goldberg et al. (31) suggested that increased alcohol consumption was associated with firearm ownership and storing a loaded firearm for males, but not for females. Although positive blood alcohol content was not associated with suicide by firearm, Conner et al. (11) found significant interactions between positive blood alcohol content and age in determining the method of suicide. Specifically, during young and middle adulthood, positive blood alcohol content was associated with increased odds of suicide by firearm (vs. hanging or poisoning), but in old adulthood, it was associated with decreased odds of firearm suicide.

The association between substance use and psychiatric disorders also complicates the interpretation of findings for substance use and gun-related behaviors (25, 32). One study showed that the strength of the association between antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) and gun carrying was much stronger than the association between alcohol/cocaine dependence and gun carrying (32). Bovasso (25) found that the association between drug abuse and gun threats was suppressed by the introduction of ASPD in the adjusted logistic regression model.

Given the diversity in measures and definitions for substance use behaviors and gun-related activities, the aim of this study is to help synthesize findings from previous studies of associations between substance use and gun-related activities. To help evaluate their associations, we categorized gun-related activities into 4 groups (gun access/possession, gun carrying, unsafe gun handling, and gun violence), and we determined the type of substance use (alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, cocaine/crack, drugs in general, substances in general) with each group of gun-related variable to clarify their associations. We also reviewed the associations between nonsubstance covariates including demographic characteristics (i.e., sex, age, and race/ethnicity), behavioral risk factors (especially mental health status), and gun activities to understand their contributions to heterogeneous findings.

METHODS

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

We searched through PubMed, Embase, and PsycINFO for observational studies investigating the association between substance-related behaviors, including substance use, abuse, and dependence, and gun-related behaviors. The following terms were used to search in each database: “(substance OR drug OR alcohol OR drinking OR cocaine OR crack OR marijuana OR cannabis OR tobacco OR cigarette OR smoking) AND (gun OR firearm).” We restricted studies to “humans,” “English,” and “journal articles” published between January 1, 1990, and December 22, 2014. Additional records were identified through reference lists of relevant articles. Studies were included in the review if they used individual-level data to assess 1) substance or drug use in general or consumption of specific substances including alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and cocaine/crack; 2) gun-related outcomes including gun possession, carrying, handling, and violence (e.g., firearm-related suicide or homicide); and 3) their association. We excluded 1) review articles, 2) studies without a comparison group (e.g., studies involving only suicide victims by firearm), and 3) ecological studies.

Screening procedure and review strategy

Records identified through the 3 databases were initially screened for duplication and then by titles, abstracts, and full texts sequentially. After removing duplicates, we excluded irrelevant titles and abstracts primarily on the basis of the 3 inclusion criteria. Full-text files of the remaining articles were retrieved and reviewed systematically. Studies meeting all 3 inclusion criteria were included in the review and assessed by the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist (33, 34). Data from eligible studies were extracted to a standardized form that contains the following information (if available): geographical location of the study; study period or year of data collection; sample demographics (sample size, mean age, age range, sex, and racial composition); mental health status of subjects; explanations for measures of substance use and gun-related outcome; and primary results regarding the association between these 2 variables. In cases where multiple types of substance use and gun-related behaviors were examined by the study, we recorded all the information. We further grouped estimated adjusted odds ratios for gun-related outcomes from individual studies by each combination of a substance category and a gun-related behavior type to facilitate comparisons across studies.

Classification of measures for substance use and gun-related behaviors

Gun-related behaviors

Largely following the terms used in individual studies, we divided gun-related behaviors into 4 categories in the meta-analysis/regression. Studies examining firearm access (35) or possession (36–43) were grouped into the first category. The second category included studies investigating gun carrying (29, 32, 41, 44–48). Third, gun handling included unsupervised gun handling among adolescents (19, 49) and households with loaded and unlocked firearms (50). Fourth, gun violence contained studies investigating subjects that actually used a gun including child gun use (51), gun threat or assault (25, 26, 40, 41, 52, 53), firearm homicide (54–56), and self-inflicted gun injury or suicide (11, 14, 57–64).

Substance use

Substances were classified into alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, cocaine/crack, drugs in general, and substances in general, depending on the definitions from the original studies. It was impossible to disentangle individual substances used in studies that examined drug use/abuse/dependence in general (25, 26, 29, 42, 46, 56, 57, 60, 64, 65) and substance use/abuse/dependence in general (26, 35, 45, 55, 59, 62, 66). They were included in the analysis as broad categories. Alcohol use was sometimes examined in various forms in one study (39, 40, 42–44, 48, 49, 52, 53, 58), such as light/moderate drinking and heavy/excessive/binge drinking (40, 44, 52, 53, 58). Other studies used different measures such as positive blood alcohol content (54, 57, 64) and alcohol abuse or dependence (25, 32).

RESULTS

Description of included studies

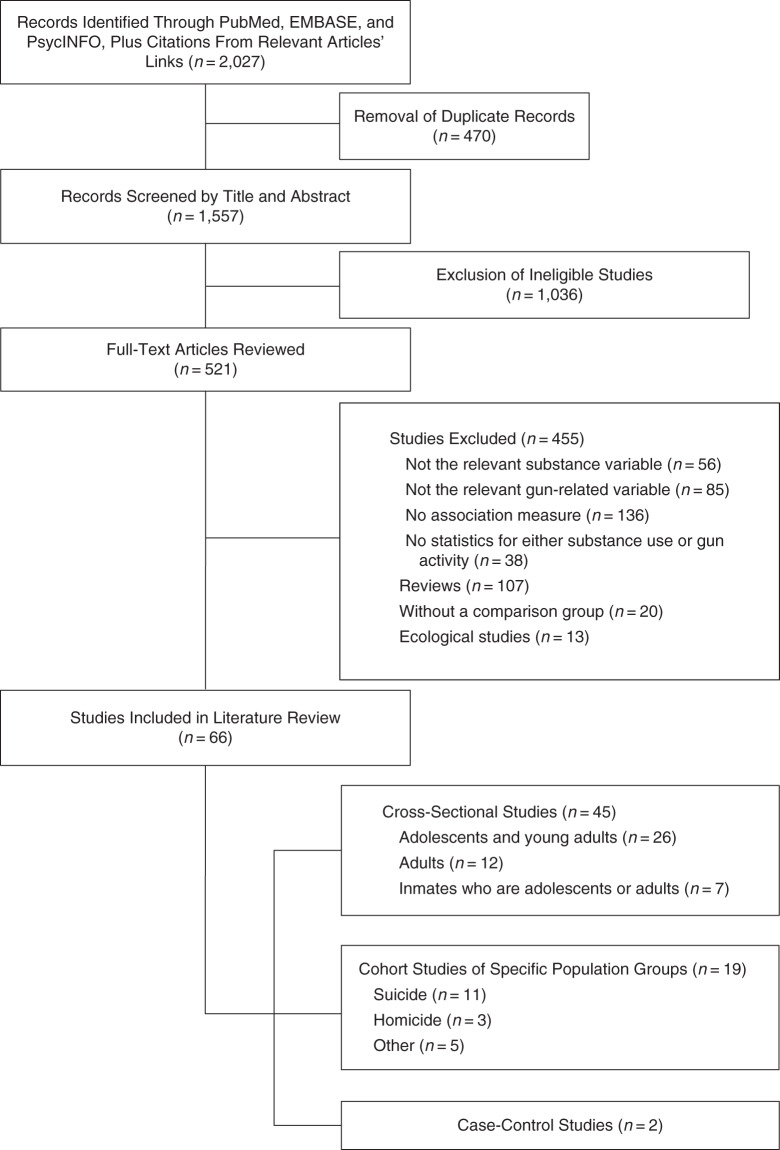

A total number of 2,027 records were retrieved from 3 databases and the reference lists of relevant studies (Figure 2). After removal of 470 duplicate records, there were 1,557 records left for screening. Reading through titles and abstracts identified 1,036 irrelevant records. Out of 521 full-text articles, 455 did not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, 66 studies (including 45 cross-sectional studies, 19 cohort studies, and 2 case-control studies) were included in our review. The overall reporting quality of these studies was moderate to high using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist (Web Table 1 available at http://epirev.oxfordjournals.org/). However, low compliance was found in several items that included using commonly used terms to indicate study design in the title and abstract (item 1a), describing efforts to address potential sources of bias (item 9), sensitivity analyses (item 12e), and so on. The reporting quality, sample characteristics, and relevant results of each study were summarized in Web Table 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of article identification.

Direction of association

With 4 exceptions, almost all of the studies included in this review used substance use as an independent variable for gun activity in a multivariate framework. Markowitz (48) used 2-stage least squares to adjust for the bias associated with the possibility of reverse causality or an unobserved factor contributing to the association. Contrary to most studies, the one by Wintemute (43) used firearm-related behaviors as an independent variable for alcohol consumption and found that people who engaged in firearm-related behaviors were more likely to consume alcohol than those who did not. Marzuk et al. (14) suggested that people who committed suicide by firearm were twice as likely to use cocaine in days prior to death. Using the 2001 California Health Interview Survey, Vittes and Sorenson (42) found that, compared with adolescents who were able to get a handgun within 2 days, those who were unable to get a handgun were less likely to engage in a set of health risk behaviors including various measures of substance use.

Bivariate association without adjustment

The majority of measures for bivariate association without adjustment for potential confounders indicated that there was a significantly positive association between substance use and gun activity. However, there were also findings indicating a nonsignificant relationship even without adjustment (46, 67–70).

Studies comparing the association without and with adjustment

A number of studies compared the results before versus results after controlling for demographic characteristics and other behavioral risk factors. Some found that the association was no longer significant after adjustment (32, 37, 38, 59), while others showed that the odds ratio estimates decreased but remained statistically significant in some cases (22, 64, 71). Both types of studies used multivariate logistic models to control for the covariates. They differed mainly in terms of specific covariates adjusted in the models (the covariates for each study were described in Web Table 2). Studies that found no significant association tended to control for more behavioral risk factors than those that did find a significant association.

Comparison of adjusted odds ratios by substance and gun-related behavior group

Adjusted odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals where available for each combination of a substance category and a gun-related outcome type are presented in ascending order in Table 1. Statistical significance based on P values reported from individual studies was obtained. Where P values were not available, they were calculated by using the formula from Altman and Bland (72). Overall, fewer significant findings after adjustment were observed for gun access/possession than other gun-related outcomes.

Table 1.

Comparison of Adjusted Odds Ratios by Substance and Gun-Related Behavior Group

| First Author, Year (Reference No.) | Gun-Related Behavior Category | Measure of Substance Use as an Independent Variable | Measure of Gun-Related Behavior as the Dependent Variable | AORa | 95% CI | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | ||||||

| Miller, 2009 (28) | Access/possession | Alcohol dependence | Home with firearms | 0.50 | 0.30, 1.00 | |

| Miller, 1999 (39) | Access/possession | At least 5 drinks in a row in past 2 weeks (yes vs. no) | Have a working firearm at college | 0.90 | 0.70, 1.20 | |

| Miller, 2002 (40) | Access/possession | Non-binge drinker vs. nondrinker | Have a working firearm at college | 0.90 | ||

| Miller, 2009 (28) | Access/possession | Alcohol abuse | Home with firearms | 0.90 | 0.60, 1.30 | |

| Miller, 2002 (40) | Access/possession | Binge, do not drive vs. nondrinker | Have a working firearm at college | 1.60 | <0.01 | |

| Loh, 2010 (22) | Access/possession | Binge drinking | Handgun access (could you get a handgun if you wanted to?) | 1.75 | 1.37, 2.27 | <0.001 |

| Miller, 1999 (39) | Access/possession | Need alcoholic drink first thing in the morning (yes vs. no) | Have a working firearm at college | 2.00 | 1.30, 3.10 | <0.001 |

| Miller, 2002 (40) | Access/possession | Binge and drive vs. nondrinker | Have a working firearm at college | 2.30 | <0.001 | |

| Simon, 1998 (74) (female) | Carrying | Lifetime alcohol use, no. of occasions (1–4 vs. 0) | Handgun carrying in 12th grade | 1.06 | 0.45, 2.49 | |

| Nelson, 1996 (102) | Carrying | At least 60 drinks in past month | Carried loaded firearms in past month | 1.10 | 0.40, 3.00 | |

| Simon, 1998 (74) (male) | Carrying | Lifetime alcohol use, no. of occasions (1–4 vs. 0) | Handgun carrying in 12th grade | 1.11 | 0.70, 1.74 | |

| Johnson, 2012 (32) | Carrying | Alcohol dependence | Lifetime gun carrying | 1.25 | 0.87, 1.80 | |

| Nelson, 1996 (102) | Carrying | At least 5 drinks at least 1 time in past month | Carried loaded firearms in past month | 1.50 | 0.90, 2.40 | |

| Cunningham, 2010 (20) | Carrying | Binge drinking in past year | Carrying a gun in the past year | 1.54 | 0.93, 2.56 | <0.1 |

| Bergstein, 1996 (19) | Carrying | At least 4 drinks in at least 1 occasion in the past month | Ever carried a concealed gun | 1.80 | <0.05 | |

| Simon, 1998 (74) (male) | Carrying | Lifetime alcohol use, no. of occasions (5 or more vs. 0) | Handgun carrying in 12th grade | 1.86 | 1.20, 2.88 | <0.01 |

| Carlini-Marlatt, 2003 (44) | Carrying | Public school: drinkers vs. abstainers | Carried a gun | 2.40 | 0.49, 11.89 | |

| Peleg-Oren, 2009 (73) | Carrying | Very early drinkers vs. early drinkers | Carried a handgun in past 30 days | 2.48 | 1.93, 3.18 | <0.001 |

| Simon, 1998 (74) (female) | Carrying | Lifetime alcohol use, no. of occasions (5 or more vs. 0) | Handgun carrying in 12th grade | 3.68 | 1.64, 8.25 | <0.01 |

| Carlini-Marlatt, 2003 (44) | Carrying | Private school: drinkers vs. abstainers | Carried a gun | 3.80 | 0.84, 17.12 | <0.1 |

| DuRant, 1999 (76) | Carrying | Alcohol use | Ever carry a gun on school property | 4.59 | 1.27, 16.58 | <0.05 |

| Peleg-Oren, 2009 (73) | Carrying | Very early drinkers vs. nondrinkers | Carried a handgun in past 30 days | 5.56 | 3.68, 8.40 | <0.001 |

| Peleg-Oren, 2009 (73) | Carrying | Very early drinkers vs. early drinkers | Carried a gun in past 30 days | 5.65 | 3.09, 10.31 | <0.001 |

| Carlini-Marlatt, 2003 (44) | Carrying | Public school: episodic heavy drinking vs. abstainers | Carried a gun | 5.82 | 1.12, 30.30 | <0.05 |

| Carlini-Marlatt, 2003 (44) | Carrying | Private school: episodic heavy drinking vs. abstainers | Carried a gun | 17.00 | 3.86, 74.79 | <0.001 |

| Peleg-Oren, 2009 (73) | Carrying | Very early drinkers vs. nondrinkers | Carried a gun in past 30 days | 29.41 | 6.58, 125.00 | <0.001 |

| Nelson, 1996 (102) | Handling | At least 5 drinks at least 1 time in past month | Live in households with firearms always or sometimes loaded and unlocked | 1.70 | 1.30, 2.30 | <0.001 |

| Nelson, 1996 (102) | Handling | At least 60 drinks in past month | Live in households with firearms always or sometimes loaded and unlocked | 1.80 | 1.20, 2.70 | <0.01 |

| Bergstein, 1996 (19) | Handling | At least 4 drinks in at least 1 occasion in the past month | Ever handled a gun without adult knowledge/supervision | 1.90 | 1.20, 3.00 | <0.01 |

| Miller, 2004 (49) | Handling | Ever drinking | Ever handled a gun without adult knowledge/supervision | 2.90 | 1.70, 4.70 | <0.001 |

| Miller, 2004 (49) | Handling | Binge drinking in past month | Ever handled a gun without adult knowledge/supervision | 7.90 | 4.90, 12.90 | <0.001 |

| Branas, 2009 (52) | Violence | Light drinking vs. no drinking | Fatal gun assault | 0.27 | 0.02, 2.97 | |

| Branas, 2009 (52) | Violence | Drinking vs. no drinking | Fatal gun assault | 0.32 | 0.03, 3.11 | |

| Reid, 2001 (79) | Violence | Got drunk | First criminal gun use | 0.43 | <0.001 | |

| Sevigny, 2015 (80) | Violence | Used alcohol at offense | Gun use/carrying/possession during offense | 0.95 | ||

| Conner, 2014 (11) | Violence | Positive BAC | Firearm vs. hanging | 1.02 | 0.96, 1.08 | |

| Conner, 2014 (11) | Violence | Positive BAC | Firearm vs. poisoning | 1.03 | 0.97, 1.09 | |

| Piper, 2006 (64) | Violence | Alcohol detected | Firearm-related suicide vs. other methods of suicide | 1.09 | 0.94, 1.25 | |

| Hemenway, 2004 (53) | Violence | Drinker but not binge vs. nondrinker | Ever having been threatened with a gun | 1.10 | 0.60, 1.90 | |

| Branas, 2009 (52) | Violence | Light drinking vs. no drinking | Gun assault | 1.16 | 0.42, 3.22 | |

| Conner, 2014 (11) | Violence | Continuous BAC | Firearm vs. hanging | 1.17 | 1.13, 1.22 | <0.001 |

| Bovasso, 2014 (25) | Violence | Alcohol abuse or dependence | Gun threat | 1.19 | ||

| Hemenway, 2004 (53) | Violence | Binge drinker vs. nondrinker | Ever having been threatened with a gun | 1.20 | 0.70, 2.10 | |

| Miller, 2002 (40) | Violence | Non-binge drinker vs. nondrinker | Threatened/otherwise victimized by gun at college | 1.20 | ||

| Branas, 2009 (52) | Violence | Drinking vs. no drinking | Gun assault | 1.33 | 0.54, 3.31 | |

| Conner, 2014 (11) | Violence | Continuous BAC | Firearm vs. poisoning | 1.47 | 1.40, 1.54 | <0.001 |

| Casiano, 2008 (26) | Violence | Alcohol abuse/dependence | Threaten others with a gun in lifetime | 1.62 | 0.98, 2.68 | <0.1 |

| Tewksbury, 2010 (81) | Violence | Alcohol present | Firearm suicide vs. hanging | 1.68 | <0.1 | |

| Lester, 2012 (63) | Violence | Alcohol abuse | Firearm suicide vs. hanging | 1.81 | ||

| Branas, 2011 (58) | Violence | Nonexcessive drinking vs. no drinking | Self-inflicted gun injury | 1.83 | 0.81, 4.13 | |

| Miller, 2002 (40) | Violence | Binge, do not drive vs. nondrinker | Threatened/otherwise victimized by gun at college | 2.10 | ||

| Lester, 2012 (63) | Violence | Alcohol present | Firearm suicide vs. hanging | 2.50 | ||

| Branas, 2011 (58) | Violence | Nonexcessive drinking vs. no drinking | Gun suicides | 2.54 | 1.07, 6.00 | <0.05 |

| Lester, 2012 (63) | Violence | Drunk in prior days | Firearm suicide vs. hanging | 2.64 | ||

| Branas, 2009 (52) | Violence | Heavy drinking vs. no drinking | Gun assault | 2.67 | 0.90, 7.87 | <0.1 |

| Casiano, 2008 (26) | Violence | Alcohol dependence | Threaten others with a gun in lifetime | 2.91 | 1.92, 4.43 | <0.001 |

| Casiano, 2008 (26) | Violence | Alcohol abuse | Threaten others with a gun in lifetime | 3.21 | 2.31, 4.45 | <0.001 |

| Miller, 2002 (40) | Violence | Binge and drive vs. nondrinker | Threatened/otherwise victimized by gun at college | 4.10 | <0.01 | |

| Branas, 2011 (58) | Violence | Drinking vs. no drinking | Self-inflicted gun injury | 4.23 | 2.25, 7.98 | <0.001 |

| Branas, 2011 (58) | Violence | Drinking vs. no drinking | Gun suicides | 5.94 | 2.91, 12.14 | <0.001 |

| Branas, 2009 (52) | Violence | Heavy drinking vs. no drinking | Fatal gun assault | 6.20 | 0.42, 92.47 | |

| Branas, 2011 (58) | Violence | Excessive drinking vs. no drinking | Self-inflicted gun injury | 77.11 | 8.76, 678.38 | <0.001 |

| Branas, 2011 (58) | Violence | Excessive drinking vs. no drinking | Gun suicides | 85.75 | 10.04, 732.27 | <0.001 |

| Tobacco | ||||||

| Miller, 2002 (40) | Access/possession | Cigarettes (yes vs. no in past 30 days) | Have a working firearm at college | 1.30 | ||

| Simon, 1998 (74) (female) | Carrying | No. of cigarettes smoked in lifetime (1–4 vs. 0) | Handgun carrying in 12th grade | 0.99 | 0.49, 2.04 | |

| DuRant, 1999 (76) | Carrying | No. of days smoked in the past month | Ever carry a gun on school property | 1.34 | 1.14, 1.57 | <0.001 |

| Simon, 1998 (74) (male) | Carrying | No. of cigarettes smoked in lifetime (1–4 vs. 0) | Handgun carrying in 12th grade | 1.89 | 1.31, 2.72 | <0.001 |

| Simon, 1998 (74) (male) | Carrying | No. of cigarettes smoked in lifetime (5 or more vs. 0) | Handgun carrying in 12th grade | 2.22 | 1.45, 3.39 | <0.001 |

| Simon, 1998 (74) (female) | Carrying | No. of cigarettes smoked in lifetime (5 or more vs. 0) | Handgun carrying in 12th grade | 5.12 | 2.74, 9.59 | <0.001 |

| Bergstein, 1996 (19) | Carrying | One or more cigarettes smoked last week vs. none | Ever carried a concealed gun | 5.50 | <0.05 | |

| Miller, 2004 (49) | Handling | Ever smoked cigarettes regularly (at least 1 cigarette every day for 30 days) | Ever handled a gun without adult knowledge/supervision | 2.80 | 1.70, 4.70 | <0.001 |

| Bergstein, 1996 (19) | Handling | One or more cigarettes smoked last week vs. none | Ever handled a gun without adult knowledge/supervision | 3.70 | 2.20, 6.30 | <0.001 |

| Miller, 2002 (40) | Violence | Cigarettes (yes vs. no in past 30 days) | Threatened/otherwise victimized by gun at college | 0.90 | ||

| Hemenway, 2004 (53) | Violence | Ever smoked cigarettes regularly (at least 1 cigarette every day for 30 days) | Ever having been threatened with a gun | 6.20 | 3.90, 9.90 | <0.001 |

| Marijuana | ||||||

| Miller, 1999 (39) | Access/possession | Marijuana use since the beginning of the term (yes vs. no) | Have a working firearm at college | 0.90 | 0.70, 1.20 | |

| Miller, 2002 (40) | Access/possession | Marijuana (yes vs. no in past 30 days) | Have a working firearm at college | 0.90 | ||

| Loh, 2010 (22) | Access/possession | Marijuana use (yes vs. no in past year) | Handgun access (could you get a handgun if you wanted to?) | 1.93 | 1.58, 2.36 | <0.001 |

| Steinman, 2003 (75) | Carrying | Marijuana use (continuous index) | Episodic gun carriers vs. noncarrier | 1.03 | 1.01, 1.06 | <0.01 |

| Simon, 1998 (74) (female) | Carrying | Lifetime marijuana use, no. of occasions (1–4 vs. 0) | Handgun carrying in 12th grade | 1.48 | 0.72, 3.03 | |

| Simon, 1998 (74) (male) | Carrying | Lifetime marijuana use, no. of occasions (1–4 vs. 0) | Handgun carrying in 12th grade | 2.11 | 1.37, 3.24 | <0.001 |

| Simon, 1998 (74) (male) | Carrying | Lifetime marijuana use, no. of occasions (5 or more vs. 0) | Handgun carrying in 12th grade | 2.31 | 1.41, 3.80 | <0.001 |

| Cunningham, 2010 (20) | Carrying | Past-year marijuana use | Carrying a gun in the past year | 3.33 | 2.13, 5.26 | <0.001 |

| Simon, 1998 (74) (female) | Carrying | Lifetime marijuana use, no. of occasions (5 or more vs. 0) | Handgun carrying in 12th grade | 3.57 | 1.77, 7.22 | <0.001 |

| DuRant, 1999 (76) | Carrying | Marijuana use | Ever carry a gun on school property | 3.66 | 1.67, 8.06 | <0.001 |

| Vaughn, 2012 (77) | Carrying | Lifetime marijuana use | Handgun carrying | 4.12 | 3.16, 5.37 | <0.001 |

| Reid, 2001 (79) | Violence | Smoked marijuana | First criminal gun use | 0.37 | <0.001 | |

| Miller, 2002 (40) | Violence | Marijuana (yes vs. no in past 30 days) | Threatened/otherwise victimized by gun at college | 1.90 | <0.05 | |

| Cocaine/crack | ||||||

| Miller, 2002 (40) | Access/possession | Cocaine (yes vs. no in past 30 days) | Have a working firearm at college | 0.90 | ||

| Miller, 1999 (39) | Access/possession | Cocaine or crack use since the beginning of the term (yes vs. no) | Have a working firearm at college | 1.30 | 1.00, 1.70 | <0.1 |

| Miller, 2002 (40) | Access/possession | Crack (yes vs. no in past 30 days) | Have a working firearm at college | 2.90 | ||

| Narvaez, 2014 (71) | Access/possession | Lifetime crack cocaine use (yes vs. no) | Firearm possession at home | 5.38 | 1.17, 24.79 | <0.05 |

| Johnson, 2012 (32) | Carrying | Cocaine dependence | Lifetime gun carrying | 0.83 | 0.56, 1.23 | |

| DuRant, 1999 (76) | Carrying | Cocaine use | Ever carry a gun on school property | 2.96 | 1.29, 6.82 | <0.05 |

| Vaughn, 2012 (77) | Carrying | Lifetime cocaine or crack use | Handgun carrying | 7.68 | 5.06, 11.65 | <0.001 |

| Miller, 2002 (40) | Violence | Cocaine (yes vs. no in past 30 days) | Threatened/otherwise victimized by gun at college | 0.90 | ||

| Piper, 2006 (64) | Violence | Cocaine detected | Firearm-related suicide vs. other methods of suicide | 1.09 | 0.90, 1.34 | |

| Piper, 2006 (64) | Violence | Cannabis detected | Firearm-related suicide vs. other methods of suicide | 1.87 | 1.44, 2.44 | <0.001 |

| Miller, 2002 (40) | Violence | Crack (yes vs. no in past 30 days) | Threatened/otherwise victimized by gun at college | 6.40 | <0.001 | |

| Drug | ||||||

| Pelucio, 2011 (78) | Access/possession | Drug use | Ability to access a loaded gun in <3 hours | 0.40 | 0.10, 1.20 | |

| Miller, 2009 (28) | Access/possession | Drug abuse | Home with firearms | 0.80 | 0.50, 1.50 | |

| Miller, 2009 (28) | Access/possession | Drug dependence | Home with firearms | 0.90 | 0.30, 2.70 | |

| Carter, 2013 (65) | Access/possession | Illicit drug use (cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, hallucinogens, marijuana, or street opioids) in past 6 months | Gun carrying or gun ownership within the past 6 months | 1.63 | 1.10, 2.42 | <0.05 |

| Anteghini, 2001 (29) (female) | Carrying | Drug use | Carrying a gun in the past month | 3.54 | <0.01 | |

| Anteghini, 2001 (29) (male) | Carrying | Drug use | Carrying a gun in the past month | 3.91 | <0.001 | |

| Reid, 2001 (79) | Violence | Tried hard drugs | First criminal gun use | 1.34 | <0.001 | |

| Sevigny, 2015 (80) | Violence | Used drugs at offense | Gun use/carrying/possession during offense | 1.56 | <0.05 | |

| Casiano, 2008 (26) | Violence | Drug abuse/dependence | Threaten others with a gun in lifetime | 1.74 | 0.89, 3.40 | |

| Tewksbury, 2010 (81) | Violence | Drugs present | Firearm suicide vs. hanging | 1.76 | <0.1 | |

| Bovasso, 2014 (25) | Violence | Drug abuse or dependence | Gun threat | 1.79 | ||

| Casiano, 2008 (26) | Violence | Drug abuse | Threaten others with a gun in lifetime | 3.84 | 2.65, 5.56 | <0.001 |

| Casiano, 2008 (26) | Violence | Drug dependence | Threaten others with a gun in lifetime | 5.59 | 3.53, 8.85 | <0.001 |

| Substance | ||||||

| Ilgen, 2008 (27) | Access/possession | Drug or alcohol use disorder | Had 1 or more guns in working condition in the home | 0.80 | 0.70, 1.00 | |

| Miller, 2009 (28) | Access/possession | Any of substance use disorders | Home with firearms | 0.90 | 0.60, 1.30 | |

| Kolla, 2011 (35) | Access/possession | Comorbid substance use diagnosis | Access to firearms | 1.05 | 0.43, 2.55 | |

| Kolla, 2011 (35) | Access/possession | Primary substance use disorder | Access to firearms | 3.69 | 0.90, 15.19 | <0.1 |

| Ilgen, 2008 (27) | Carrying | Drug or alcohol use disorder | Carried a gun outside the home in the past 30 days | 0.80 | 0.60, 1.20 | |

| Williams, 2002 (82) | Carrying | 30-day substance use | Ever carried (vs. never carried) | 1.38 | 1.08, 1.76 | <0.01 |

| Hemenway, 2011 (45) | Carrying | Any substance use (past 30 days, including alcohol; tobacco; or marijuana and other illegal drugs) | Ever carried a gun in the past year | 2.40 | <0.01 | |

| Williams, 2002 (82) | Carrying | 30-day substance use | Ever took to school (vs. never took) | 4.30 | 1.62, 11.45 | <0.01 |

| Williams, 2002 (82) | Carrying | 30-day substance use | Ever carried and took to school (vs. never took) | 4.41 | 1.45, 13.43 | <0.01 |

| Ilgen, 2008 (27) | Handling | Drug or alcohol use disorder | Had a gun stored unlocked and loaded | 1.00 | 0.60, 1.60 | |

| de Moore, 1999 (59) | Violence | Drug and alcohol use | Suicide by firearm vs. jumping | 0.05 | 0.00, 6.30 | |

| Hempstead, 2013 (62) | Violence | Substance abuse (including alcohol use) | Firearm suicide vs. other methods | 0.81 | 0.66, 1.01 | <0.1 |

| Callanan, 2012 (30) (mixed sexes) | Violence | History of drug abuse (recently abused alcohol, prescription drug, and illicit drug) | Suicide by firearm vs. other methods | 0.81 | 0.50, 1.30 | |

| Callanan, 2012 (30) (male) | Violence | History of drug abuse (recently abused alcohol, prescription drug, and illicit drug) | Suicide by firearm vs. other methods | 0.84 | 0.49, 1.43 | |

| Callanan, 2012 (30) (female) | Violence | History of drug abuse (recently abused alcohol, prescription drug, and illicit drug) | Suicide by firearm vs. other methods | 0.85 | 0.28, 2.59 | |

| Martone, 2013 (66) | Violence | Substance use disorder | Use of firearm in offense | 2.34 | 0.74, 7.44 | |

| Casiano, 2008 (26) | Violence | Any substance disorder | Threaten others with a gun in lifetime | 3.25 | 2.35, 4.49 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; BAC, blood alcohol content; CI, confidence interval.

a Coefficients from logit regressions were converted to odds ratios.

b Only P values that were less than 0.1 are shown in the table.

Alcohol use

Compared with studies of people who did not consume alcohol heavily, studies among those drinking alcohol heavily indicated that there were increased odds of gun access/possession (22, 40). The majority of studies indicated that there was a significant association between heavy drinking and gun carrying. However, the adjusted odds ratios varied substantially across studies. For example, it was found by Bergstein et al. (19) that consuming more than 4 drinks on at least 1 occasion in the past month was associated with an 80% increase in the odds of ever carrying a concealed gun (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1.8). On the basis of the 2005 Florida Youth Risk Behavior Survey, Peleg-Oren et al. (73) found that the odds for very early drinkers were 29 times the odds for nondrinkers to carry a gun in past 30 days (AOR = 29.41, 95% confidence interval (CI): 6.58, 125.00). All 3 studies included in Table 1 indicated a significant association between alcohol use and unsafe gun handling after adjustment.

Findings regarding the association between alcohol use and gun violence are mixed. Two case-control studies (52, 58) took population-based random samples from people at risk of being shot to match cases who were actually involved in gun assault or self-inflicted gunshot injury in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Branas et al. (52) found that light drinkers were not at significantly higher risk of being shot in an assault than were nondrinkers (AOR = 1.16, 95% CI: 0.42, 3.22), whereas heavy drinkers were (AOR = 2.67, 95% CI: 0.90, 7.87; P < 0.1). The study by Branas et al. (58) identified a stronger association between alcohol use (specifically, excessive drinking) and self-inflicted gun injury/gun suicide than other studies did. Using data for adult suicide decedents from the 2005–2010 National Violent Death Reporting System database, Conner et al. (11) found that positive blood alcohol content (defined as a dichotomous variable) was not associated with suicide by firearm (vs. poisoning or hanging). Further analyses, though, with a subsample of decedents whose blood alcohol content was equal to or greater than 0.01 g/dL suggested that higher blood alcohol content was associated with increased odds of suicide by firearm versus hanging (AOR = 1.17, 95% CI: 1.13, 1.22) and suicide by firearm versus poisoning (AOR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.40, 1.54).

Tobacco use

Miller et al. (40) did not find a significant association between smoking cigarettes and gun ownership at college. Three studies found that smokers had higher odds of carrying a gun than did nonsmokers. For example, Simon et al. (74) examined data from a longitudinal survey of adolescent substance use in San Diego and Los Angeles counties of California and found that students who smoked cigarettes in the ninth grade were more likely to report handgun carrying in the 12th grade, compared with nonsmokers. This association held for boys who smoked 1–4 cigarettes (AOR = 1.89, 95% CI: 1.31, 2.72) and 5 or more cigarettes (AOR = 2.22, 95% CI: 1.45, 3.39) and for girls who smoked 5 or more cigarettes (AOR = 5.12, 95% CI: 2.74, 9.59) in their lifetime. In terms of gun handling, both Miller and Hemenway (49) and Bergstein et al. (19) found that adolescent smokers had higher odds of ever handling a gun without adult knowledge/supervision than did nonsmokers. Hemenway and Miller (53) found that adolescent smokers were associated with higher odds of ever being threatened with a gun, compared with nonsmokers (AOR = 6.2, 95% CI: 3.9, 9.9).

Marijuana use

Using data from the 1997 and 2001 College Alcohol Study, respectively, Miller et al. (39, 40) did not find a significant association between marijuana use and having a working firearm at college. On the other hand, Loh et al. (22) found that teens who used marijuana in the year prior to presenting to an urban emergency department had higher odds of handgun access than did nonusers (AOR = 1.93, 95% CI: 1.58, 2.36).

The majority of studies found that marijuana users had higher odds of gun carrying than did nonusers. Steinman and Zimmerman (75) examined gun-carrying behaviors in a group of urban African-American public high school students and found that an increased frequency of marijuana use was associated with higher odds of episodic gun-carrying (AOR = 1.03, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.06). Similar to findings regarding the association between tobacco use and gun carrying, Simon et al. (74) found that marijuana use in the ninth grade was associated with increased odds of gun carrying in the 12th grade except for when marijuana use was measured as 1–4 occasions versus 0 in lifetime for girls. Another 3 studies (20, 76, 77) suggested that the odds for marijuana users were 3–4 times the odds for nonusers in carrying a gun.

Although Miller et al. (40) did not find a significant association between marijuana use and firearm ownership at college, they found that past-month marijuana use was associated with increased odds of being threatened or victimized by a gun at college (AOR = 1.9; P < 0.05).

Cocaine/crack use

Narvaez et al. (71) examined violent and sexual behaviors and crack cocaine use in a population-based sample of adults aged 18–24 years from Brazil and found that lifetime crack cocaine users were associated with having increased odds of firearm possession at home, compared with nonusers (AOR = 5.38, 95% CI: 1.17, 24.79). Two other studies found only a less significant (39) or insignificant (40) association.

After adjustment for a number of demographics and personal lifestyle risk factors, Johnson et al. (32) found that cocaine dependence was not associated with lifetime gun carrying in an urban sample of female out-of-treatment substance users. DuRant et al. (76) found that cocaine use was associated with increased odds of gun carrying on school property after controlling for sex and race/ethnicity (AOR = 2.96, 95% CI: 1.29, 6.82). Vaughn et al. (77) examined gun carrying behaviors in a population-based sample of adolescents aged 12–17 years and found that the odds for lifetime cocaine or crack users were more than 7 times the odds for nonusers (AOR = 7.68, 95% CI: 5.06, 11.65), even after adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, family income, lifetime depression, and anxiety.

On the basis of all suicide deaths between 1990 and 2000 from New York, New York, Piper et al. (64) found that the odds of using a firearm in suicide for decedents detected with cannabis (but not for those detected with cocaine) were 87% higher than the odds for those not detected with cannabis (AOR = 1.87, 95% CI: 1.44, 2.44). Miller et al. (40) found that crack use (but not cocaine use) was strongly associated with being threatened or victimized by a gun at college (AOR = 6.4; P < 0.001).

Drug use in general

Two of the 3 studies (28, 78) listed in Table 1 did not find a significant association between drug use in general and access to or possession of guns. Anteghini et al. (29) examined the health risk behaviors among a sample of eighth and 10th graders in Brazil and found that the odds of carrying a gun in the past month for drug users were more than 3 times the odds for nonusers (for boys, AOR = 3.91; P < 0.001; for girls, AOR = 3.54; P = 0.007). In contrast to the negative association between alcohol or marijuana use and first criminal gun use, Reid (79) found that trying hard drugs was associated with increased odds of using a gun in a crime for juvenile inmates (AOR = 1.34; P < 0.001). Using data from a nationally representative survey of inmates in the United States, Sevigny and Allen (80) found that offense under the influence of drugs increased the odds of gun use/carrying/possession at offense (AOR = 1.56; P < 0.05). Tewksbury et al. (81) examined the 2003–2008 male suicides from Louisville, Kentucky, and found that presence of drugs in a decedent's body was associated with 76% higher odds of suicide by firearm rather than hanging (AOR = 1.76; P < 0.10).

Substance use in general

Findings on the association between substance use disorder and gun access/ownership were only marginal (27, 35). Two studies (45, 82) found that substance use in the past 30 days was associated with increased odds of gun carrying. Casiano et al. (26) found that the diagnosis of any substance disorder was associated with increased odds of threatening others with a gun (AOR = 3.25, 95% CI: 2.35, 4.49) while controlling for sociodemographic characteristics. Other studies listed in Table 1 did not find a significant association between substance use in general and gun-related behaviors after adjustment.

Association between demographic covariates and gun-related behaviors

Sex

The studies included in this review invariably showed that males were more likely to engage in gun-related behaviors than females were.

Age

The association between age and gun-related behaviors was less consistent across studies. Two studies (22, 53) found that older adolescents were more likely to engage in gun-related behaviors than were younger adolescents. Three studies (25, 66, 80) used adult samples and found a negative association between age and gun-related behaviors. However, age was found to be positively associated with firearm suicide (vs. other methods of suicide) in 2 studies (30, 62).

Race/ethnicity

Findings regarding racial disparities in gun-related behaviors are mixed. It is worth noting that several studies (11, 53, 64, 79) found that blacks had higher odds of involvement in gun-related behaviors than non-Hispanic whites had.

Studies adjusting for mental disorders

The majority of studies reported adjusted measures of association between various types of substance use and gun activity. They differed greatly with respect to the specific mental health conditions adjusted in the models. Mental health conditions, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (32, 60), depression (30, 32, 60, 63, 77), and anxiety (77), identified by prior studies were included in this review. The association between a mental health condition and gun violence tended to depend on model specifications. For instance, post-traumatic stress disorder and depression were associated with gun carrying behaviors in bivariate models, but not in the multivariate model (32). The associations between substance use and gun-related behaviors tended to be less significant or insignificant in most of the studies controlling for mental disorders other than substance use disorders (25, 26, 30, 32, 35, 59, 60, 66). This was particularly true when ASPD was included in a model (25, 26, 32). Compared with substance use disorders, diagnosis of ASPD was much more strongly associated with gun-related behaviors (25, 32).

A dose-response relationship

Many studies examined the association between different levels of alcohol consumption and gun-related behaviors. A unanimous finding indicated that binge or heavy drinking was more likely to be associated with heightened risk of gun activity, compared with nonexcessive or light drinking (40, 44, 52, 58, 74). One study reported a significant association between nonexcessive drinking and gun suicide (58). Most of the studies found a significantly positive association between heavy drinking and gun activity, except for 1 study (53) that didn't find a significant association for either heavy or light drinking.

Simon et al. (74) examined cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use in different frequencies and their association with handgun carrying. The finding generally indicated a positive association between the frequency of substance use and carrying a handgun. Another study (83) also found that more frequent use of hard drugs was associated with a higher frequency of gun-related victimization. Sevigny and Allen (80) divided drug quantity into 4 quartiles and found that only the fourth quartile was associated with increased odds of gun possession during commission of an offense, compared with the first quartile.

Two studies (45, 82) found that 30-day substance use in general was associated with gun carrying. Findings regarding the association between substance abuse/dependence/disorders and gun-related behaviors were mixed (26–28, 59, 60, 62, 66, 67, 70).

DISCUSSION

Without consideration of potential confounders, most of the prior findings indicated that substance use was associated with increased odds of gun-related behaviors. Findings regarding their association were mixed after adjusting for various covariates, such as sociodemographic factors, mental health status, and other behavioral risk factors. The association could hardly be detected, especially when psychiatric conditions were being controlled for. Past studies also suggested a dose-response relationship between substance use and gun activity. It has been found consistently that binge or heavy drinking is more likely to be associated with increased odds of gun activity, compared with nonexcessive or light drinking; and that there is a positive association between the frequency of substance use and gun-related behaviors. The association between substance use and gun access/possession was weaker than other gun-related outcomes. As mentioned at the beginning of this paper, violent behaviors may be promoted by psychopharmacological effects of substance use. Gun possession itself is not a violent outcome in the sense that it does not necessarily lead to gun misuse.

There was substantial heterogeneity in adjusted odds ratios between studies in each substance group and in almost every subgroup of gun activity. The inconsistent findings could be attributed to a number of factors including variations in definitions of substance use and gun activity, differences in study design, and study-specific sample demographics. There was no clear pattern as to which substance was consistently found to have a stronger association with a specific gun-related behavior. This may be related to the fact that there are high co-occurrences between different types of substance use. Compared with other study designs, the 2 case-control studies (52, 58) identified a stronger association between alcohol use and gun violence.

Demographic covariates such as sex, age, and race/ethnicity were found to be associated with gun-related behaviors. The strong association between male sex and gun activity is consistent with existing laboratory evidence that the substance-aggression relationship is stronger for men than women (84–86). The findings that older adolescents and young adults were more likely to be involved in gun-related behaviors are generally consistent with nonfatal and fatal firearm violence prevalence by age in the United States (4). Persons aged 18–24 years almost always had the highest rate of fatal and nonfatal firearm violence from 1993 to 2011. In 2010, the firearm homicide death rate was 10.7 per 100,000 persons among those aged 18–24 years, compared with 0.3, 2.8, 8.1, 3.6, and 1.4 per 100,000 persons for people aged 11 or younger, 12–17, 25–34, 35–49, and 50 or older, respectively. In 2011, the nonfatal firearm violence rate was 5.2 per 1,000 persons among those aged 18–24 years, compared with 1.4, 2.2, 1.4, and 0.7 per 1,000 persons for people aged 12–17, 25–34, 35–49, and 50 years or older, respectively. Historically, adolescents aged 12–17 years had the second highest rate of nonfatal firearm violence from 1994 to 1999, in 2003, 2007, and 2008, among the age groups abovementioned. The findings that blacks were more likely to engage in gun activities are consistent with national statistics, which show that the rates of firearm homicide and nonfatal firearm violence are higher among blacks than the other major racial groups examined (4).

The strong association between nonsubstance covariates and gun activity may have contributed to varied odds ratio estimates after adjustment. For example, Bovasso (25) found that the association between alcohol abuse and gun threats was suppressed after adding sex into the logistic regression model. A spectrum of mental disorders may have attenuated the association between substance use and gun activity. Both studies were based on the samples from the general population (25, 26), and samples from various population subgroups (30, 32, 35, 59, 60, 66) indicated that the association between substance use and gun activity was suppressed when mental disorders, especially ASPD, were included in the adjusted analyses. The 3 studies analyzed in this review (25, 26, 32) all used the criteria for ASPD from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition: DSM-IV. One of the criteria for ASPD is “irritability and aggressiveness, as indicated by repeated physical fights or assaults” (87, p. 706). This inclination toward violence may have contributed to the strong association between ASPD and gun-related behaviors.

In addion to the observational findings on the association between substance use (as well as other psychiatric covariates) and gun activities in this review, there has been experimental evidence showing that successful treatment of substance use and mental disorders is likely to decrease the level of aggression and violence in general. For instance, Zatzick et al. (88) examined the treatment effects of a collaborative care intervention targeting substance use, post-traumatic stress disorder, and depression among adolescents admitted to a US level 1 traumatic center and found that, compared with patients in the control group, those in the intervention group had significantly lower risk of weapon carrying at 12 months after injury. Mauri et al. (89) evaluated the effects of pharmacotherapy on aggression in a sample of adult psychiatric inpatients and suggested that aggression was reduced for all patients upon discharge independent of the type of medication or combination of medications received. Several randomized clinical trials indicated that behavioral interventions on persons with a substance use disorder improved their outcomes in aggression and violence (90–93).

This study had several limitations. First, the study data included in this review were subject to measurement errors, especially for studies relying on self-reported data. Delinquency and crimes were likely to be under- or overreported depending on factors such as sex, race, and frequency of arrests (94). Overreporting of arrests may be more likely to happen among adolescents than adults (94). Second, the substantial heterogeneity in study designs, sample characteristics, measures of substance use, gun-related behaviors, and other covariates limits the use of meta-analysis to identify potential sources of mixed findings. Third, as most of the studies included in this review were cross-sectional and the majority of cohort studies identified were retrospective, causality and the direction of causation cannot be inferred. In addition, the screening of search results and data extraction were done by a single researcher (D.C.), which may have lower reliability than studies done by multiple researchers.

CONCLUSION

It was consistently found that there was a significant bivariate association between substance use and increased odds of gun-related behaviors; however, there was substantial heterogeneity in their associations after adjustment (e.g., adjusted odds ratios). The mixed findings could be attributed to a number of factors, such as differences in definitions of substance use and gun activity, study design, sample demographics, and the specific covariates considered in the analysis. The number of studies showing a significant association between substance use and gun access/possession was smaller than that for other gun activities. The strong association between nonsubstance covariates (such as demographic covariates and other behavioral risk factors, especially psychiatric conditions) and gun-related outcomes might have moderated (or attenuated) the association between substance use and gun activities. Nonetheless, some studies suggested a dose-response relationship between substance use and gun-related behaviors (e.g., 74, 80, 83). The nature of observational designs of the available studies precludes causal inference.

The majority of studies included in this review merely regress gun-related outcomes on a series of independent variables specific to the objectives of the studies, without considering possible interactions between them. There is a need for more in-depth research on evaluating subgroup differences (age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status) in associations between substance use and gun-related behaviors, as well as mechanisms contributing to their differences. Additional research is needed to better characterize substance use patterns (severity, frequency, type) and the level of gun-related violence. Well-designed longitudinal studies are needed to clarify the temporal relationship between substance use and gun-related behaviors. For instance, future research should evaluate the long-term impact of preventing substance use among young people on subsequent gun-related behaviors.

Although federal law prohibits a high-risk individual who is “an unlawful user of or addicted to any controlled substance,” has been “adjudicated as a mental defective,” or “committed to any mental institution” from possessing firearms, only federally licensed firearm sellers are required to conduct background checks for prospective firearm buyers (95, p. 18). Unlicensed private sellers are not legally obliged to verify whether firearm purchasers meet the federal eligibility criteria. This suggests a need to increase compliance inspections on potential violations of gun sales laws and to expand background checks to private sellers. More stringent law enforcement would potentially reduce gun violence by people with a substance use disorder or other serious mental disorders (96). However, there are a number of practical and legal hurdles that may impede the reporting of individuals with a substance use disorder or a severe mental illness to federal databases, such as a lack of technical infrastructure, concerns about data confidentiality, and variations in state policies (97). In order to help improve the reporting of high-risk individuals to federal databases, it may be necessary to establish a better technical infrastructure with enhanced confidentiality protection and to develop policies for removing unnecessary legal barriers to reporting substance use disorders or serious mental illnesses (97). Violence risk assessment could be incorporated into assessments for psychiatric diagnoses to evaluate the risk for future violence (98). Current federal law does not prohibit alcoholics from possessing firearms (95). Given the evidence linking excessive drinking to gun-related behaviors, the severity of problem drinking or alcohol use disorder could be considered as a disqualification criterion. In particular, individuals with multiple convictions of driving under the influence of alcohol or other drugs and who may be at higher risk for violence or injuries should be prohibited from purchasing or possessing firearms (99). Mechanisms for restoring firearm rights should be in place for those under the influence of temporary prohibitions (97, 99). In addition, research is needed to inform whether and how gun restriction policies may stigmatize people with a substance use disorder or mental illness and deter their treatment seeking (97). To date, many states set 18 years as the minimum legal age for firearm purchase. As studies indicate that young adults are more likely than older adults to engage in gun-related behaviors, raising the minimum legal age for gun purchase to 21 years across the country may reduce the rates of gun activities among young adults (100). Moreover, school- and community-based initiatives for gun violence should be implemented to identify high-risk persons and offer treatment options for problem behaviors (101). Integrative prevention and care programs are needed to reduce the co-occurrence of substance misuse/addiction, mental illness, and other behavioral risk factors for gun violence.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas (Danhong Chen); Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, School of Medicine, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina (Li-Tzy Wu); and Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina (Li-Tzy Wu).

This work was made possible by research support from the National Institutes of Health (grants R01MD007658, R01DA019623, R01DA019901, R33DA027503; and UG1DA040317; Principal Investigator, L-T.W.) and by the Duke University Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences (Psychiatry 4416016).

The sponsoring agency had no further role in the study design and analysis, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. The opinions expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cerdá M, Messner SF, Tracy M et al. Investigating the effect of social changes on age-specific gun-related homicide rates in New York City during the 1990s. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(6):1107–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chauhan P, Cerdá M, Messner SF et al. Race/ethnic-specific homicide rates in New York City: evaluating the impact of broken windows policing and crack cocaine markets. Homicide Stud. 2011;15(3):268–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Opinion Research Center. General social survey 1972–2012 cumulative data R6. http://www3.norc.org/GSS+Website/Download/STATA+v8.0+Format/. Accessed February 4, 2015.

- 4.Planty M, Truman JL. Firearm Violence, 1993–2011. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, US Department of Justice; 2013. (GPO no. NCJ 241730). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fatal injury reports, national and regional, 1999–2013. http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate10_us.html. Accessed May 1, 2015.

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fatal injury reports, 1981–1998. http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate9.html. Accessed May 1, 2015.

- 7.Truman JL, Langton L. Criminal Victimization, 2013. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, US Department of Justice; 2014. (GPO no. NCJ 247648). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blumstein A, Rivara FP, Rosenfeld R. The rise and decline of homicide—and why. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:505–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blumstein A. Youth violence, guns, and the illicit-drug industry. J Crim Law Criminol. 1995;86(1):10–36. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Messner SF, Galea S, Tardiff KJ et al. Policing, drugs, and the homicide decline in New York City in the 1990s. Criminology. 2007;45(2):385–414. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conner KR, Huguet N, Caetano R et al. Acute use of alcohol and methods of suicide in a US national sample. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):171–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinz AJ, Beck A, Meyer-Lindenberg A et al. Cognitive and neurobiological mechanisms of alcohol-related aggression. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(7):400–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore TM, Stuart GL. A review of the literature on marijuana and interpersonal violence. Aggress Violent Behav. 2005;10(2):171–192. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marzuk PM, Tardiff K, Leon AC et al. Prevalence of cocaine use among residents of New York City who committed suicide during a one-year period. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(3):371–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein PJ. The drugs/violence nexus: a tripartite conceptual framework. J Drug Issues. 1985;15(4):493–506. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agnew R. Building on the foundation of general strain theory: specifying the types of strain most likely to lead to crime and delinquency. J Res Crime Delinq. 2001;38(4):319–361. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinchevsky GM, Fagan AA, Wright EM. Victimization experiences and adolescent substance use: does the type and degree of victimization matter? J Interpers Violence. 2014;29(2):299–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vermeiren R, Schwab-Stone M, Deboutte D et al. Violence exposure and substance use in adolescents: findings from three countries. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):535–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergstein JM, Hemenway D, Kennedy B et al. Guns in young hands: a survey of urban teenagers’ attitudes and behaviors related to handgun violence. J Trauma. 1996;41(5):794–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunningham RM, Resko SM, Harrison SR et al. Screening adolescents in the emergency department for weapon carriage. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):168–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for understanding and action. J Adolesc Health. 1991;12(8):597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loh K, Walton MA, Harrison SR et al. Prevalence and correlates of handgun access among adolescents seeking care in an urban emergency department. Accid Anal Prev. 2010;42(2):347–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donovan JE, Jessor R. Structure of problem behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53(6):890–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donovan JE, Jessor R, Costa FM. Syndrome of problem behavior in adolescence: a replication. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(5):762–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bovasso G. Assessing the risk of threats with guns in the general population. J Threat Assess Manag. 2014;1(1):27–39. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casiano H, Belik S-L, Cox BJ et al. Mental disorder and threats made by noninstitutionalized people with weapons in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196(6):437–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ilgen MA, Zivin K, McCammon RJ et al. Mental illness, previous suicidality, and access to guns in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(2):198–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller M, Barber C, Azrael D et al. Recent psychopathology, suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts in households with and without firearms: findings from the National Comorbidity Study replication. Inj Prev. 2009;15(3):183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anteghini M, Fonseca H, Ireland M et al. Health risk behaviors and associated risk and protective factors among Brazilian adolescents in Santos, Brazil. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28(4):295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Callanan VJ, Davis MS. Gender differences in suicide methods. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(6):857–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldberg BW, Whitlock E, Greenlick M. Firearm ownership and health care workers. Public Health Rep. 1996;111(3):256–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson SD, Cottler LB, Ben Abdallah A et al. Risk factors for gun-related behaviors among urban out-of-treatment substance using women. Subst Use Misuse. 2012;47(11):1200–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vandenbroucke JP, Von Elm E, Altman DG et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):W163–W194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Prev Med. 2007;45(4):247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kolla BP, O'Connor SS, Lineberry TW. The base rates and factors associated with reported access to firearms in psychiatric inpatients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(2):191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bennett T, Holloway K. Possession and use of illegal guns among offenders in England and Wales. Howard J Crim Justice. 2004;43(3):237–252. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Callahan CM, Rivara FP. Urban high school youth and handguns. A school-based survey. JAMA. 1992;267(22):3038–3042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Callahan CM, Rivara FP, Farrow JA. Youth in detention and handguns. J Adolesc Health. 1993;14(5):350–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller M, Hemenway D, Wechsler H. Guns at college. J Am Coll Health. 1999;48(1):7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller M, Hemenway D, Wechsler H. Guns and gun threats at college. J Am Coll Health. 2002;51(2):57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sheley JF. Drug activity and firearms possession and use by juveniles. J Drug Issues. 1994;24(3):363–382. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vittes KA, Sorenson SB. Risk-taking among adolescents who say they can get a handgun. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(6):929–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wintemute GJ. Association between firearm ownership, firearm-related risk and risk reduction behaviours and alcohol-related risk behaviours. Inj Prev. 2011;17(6):422–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carlini-Marlatt B, Gazal-Carvalho C, Gouveia N et al. Drinking practices and other health-related behaviors among adolescents of São Paulo City, Brazil. Subst Use Misuse. 2003;38(7):905–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hemenway D, Vriniotis M, Johnson RM et al. Gun carrying by high school students in Boston, MA: Does overestimation of peer gun carrying matter? J Adolesc. 2011;34(5):997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kacanek D, Hemenway D. Gun carrying and drug selling among young incarcerated men and women. J Urban Health. 2006;83(2):266–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kingery PM, Pruitt BE, Heuberger G. A profile of rural Texas adolescents who carry handguns to school. J Sch Health. 1996;66(1):18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Markowitz S. The role of alcohol and drug consumption in determining physical fights and weapon carrying by teenagers. East Econ J. 2001;27(4):409–432. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller M, Hemenway D. Unsupervised firearm handling by California adolescents. Inj Prev. 2004;10(3):163–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nordstrom DL, Zwerling C, Stromquist AM et al. Rural population survey of behavioral and demographic risk factors for loaded firearms. Inj Prev. 2001;7(2):112–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stevens MM, Gaffney CA, Tosteson TD et al. Children and guns in a well child cohort. Prev Med. 2001;32(3):201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Branas CC, Elliott MR, Richmond TS et al. Alcohol consumption, alcohol outlets, and the risk of being assaulted with a gun. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(5):906–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hemenway D, Miller M. Gun threats against and self-defense gun use by California adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(4):395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andreuccetti G, de Carvalho HB, de Carvalho Ponce J et al. Alcohol consumption in homicide victims in the city of São Paulo. Addiction. 2009;104(12):1998–2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Menezes S, Oyebode F, Haque M. Victims of mentally disordered offenders in Zimbabwe, 1980–1990. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2009;20(3):427–439. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tardiff K, Marzuk PM, Leon AC et al. Cocaine, opiates, and ethanol in homicides in New York City: 1990 and 1991. J Forensic Sci. 1995;40(3):387–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bittner JG 4th, Hawkins ML, Atteberry LR et al. Impact of traumatic suicide methods on a level I trauma center. Am Surg. 2010;76(2):176–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Branas CC, Richmond TS, Ten Have TR et al. Acute alcohol consumption, alcohol outlets, and gun suicide. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46(13):1592–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Moore GM, Robertson AR. Suicide attempts by firearms and by leaping from heights: a comparative study of survivors. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(9):1425–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Desai RA, Dausey D, Rosenheck RA. Suicide among discharged psychiatric inpatients in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Mil Med. 2008;173(8):721–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haines J, Williams CL, Lester D. Completed suicides: Is there method in their madness? Correlates of choice of method for suicide in an Australian sample of suicides. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2010;7(4-5):133–140. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hempstead K, Nguyen T, David-Rus R et al. Health problems and male firearm suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2013;43(1):1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lester D, Haines J, Williams CL. Firearm suicides among males in Australia: an analysis of Tasmanian coroners’ inquest files. Int J Mens Health. 2012;11(2):170–176. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Piper TM, Tracy M, Bucciarelli A et al. Firearm suicide in New York City in the 1990s. Inj Prev. 2006;12(1):41–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carter PM, Walton MA, Newton MF et al. Firearm possession among adolescents presenting to an urban emergency department for assault. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martone CA, Mulvey EP, Yang S et al. Psychiatric characteristics of homicide defendants. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):994–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chassin L, Piquero AR, Losoya SH et al. Joint consideration of distal and proximal predictors of premature mortality among serious juvenile offenders. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(6):689–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Loeber R, Burke JD, Mutchka J et al. Gun carrying and conduct disorder: a highly combustible combination? Implications for juvenile justice and mental and public health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(2):138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sheley JF, Zhang J, Brody CJ et al. Gang organization, gang criminal activity, and individual gang members’ criminal behavior. Soc Sci Q. 1995;76(1):53–68. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Strom TQ, Leskela J, James LM et al. An exploratory examination of risk-taking behavior and PTSD symptom severity in a veteran sample. Mil Med. 2012;177(4):390–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Narvaez JC, Jansen K, Pinheiro RT et al. Violent and sexual behaviors and lifetime use of crack cocaine: a population-based study in Brazil. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(8):1249–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Altman DG, Bland JM. How to obtain the P value from a confidence interval. BMJ. 2011;343:d2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Peleg-Oren N, Saint-Jean G, Cardenas GA et al. Drinking alcohol before age 13 and negative outcomes in late adolescence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(11):1966–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Simon TR, Richardson JL, Dent CW et al. Prospective psychosocial, interpersonal, and behavioral predictors of handgun carrying among adolescents. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(6):960–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Steinman KJ, Zimmerman MA. Episodic and persistent gun-carrying among urban African-American adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2003;32(5):356–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.DuRant RH, Krowchuk DP, Kreiter S et al. Weapon carrying on school property among middle school students. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(1):21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vaughn MG, Perron BE, Abdon A et al. Correlates of handgun carrying among adolescents in the United States. J Interpers Violence. 2012;27(10):2003–2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pelucio M, Roe G, Fiechtl J et al. Assessing survey methods and firearm exposure among adolescent emergency department patients. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(6):500–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reid LW. The drugs-guns relationship: exploring dynamic and static models. Contemp Drug Probl. 2001;28(4):651–677. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sevigny EL, Allen A. Gun carrying among drug market participants: evidence from incarcerated drug offenders. J Quant Criminol. 2015;31(3):435–458. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tewksbury R, Suresh G, Holmes RM. Factors related to suicide via firearms and hanging and leaving of suicide notes. Int J Mens Health. 2010;9(1):40–49. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Williams SS, Mulhall PF, Reis JS et al. Adolescents carrying handguns and taking them to school: psychosocial correlates among public school students in Illinois. J Adolesc. 2002;25(5):551–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sheley JF, McGee ZT, Wright JD. Gun-related violence in and around inner-city schools. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146(6):677–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fillmore MT, Weafer J. Alcohol impairment of behavior in men and women. Addiction. 2004;99(10):1237–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Giancola PR, Levinson CA, Corman MD et al. Men and women, alcohol and aggression. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;17(3):154–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Giancola PR, Zeichner A. An investigation of gender differences in alcohol-related aggression. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56(5):573–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition: DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zatzick D, Russo J, Lord SP et al. Collaborative care intervention targeting violence risk behaviors, substance use, and posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms in injured adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(6):532–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mauri MC, Rovera C, Paletta S et al. Aggression and psychopharmacological treatments in major psychosis and personality disorders during hospitalisation. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(7):1631–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fals-Stewart W, Kashdan TB, O'Farrell TJ et al. Behavioral couples therapy for drug-abusing patients: effects on partner violence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22(2):87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]