Abstract

Dentures are inert and nonshading surfaces and therefore get easily colonized by Candida species. Subsequent biofilm produced by them lead to denture stomatitis and candidiasis. This study was aimed to understand the prevalence of Candida species among healthy denture and nondenture wearers with respect to their age and hygiene status. Swabs were collected from 50 complete dentures and 50 non-denture wearers and processed on Sabouraud's dextrose agar. Identification of Candida species was done by staining and a battery of biochemical tests. Data obtained was correlated with age & oral hygiene and statistical analysis was performed. Candida was isolated from both denture and nondenture wearers. Prevalence of different Candida species was significantly higher in denture wearers and found predominated by C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. dubliensis and C. glabrata. Among nondenture wearers, C. albicans and C. tropicalis were isolated. Prevalence of Candida increased with increasing age among denture wearers. Men presented declining denture hygiene compared to women with increasing age. In comparison to nondenture wearers, multispecies of Candida colonized the dentures thus presenting higher risk of candidiasis especially with increasing age.

Keywords: Age, Candida spp., denture, gender, hygiene

INTRODUCTION

Human oral cavity is a reservoir of approximately 700 species of microorganisms including 20 species of Candida.[1,2] Candida is not considered harmful in healthy hosts but may cause opportunistic infections resulting in candidiasis.[3] Old age necessitates wearing artificial dentures which results in changes in the oral environment and consequently oral flora. Microbes from the oral environment colonize the denture surface to form adherent biofilm which is dependent on the denture characteristics, species of Candida and oral hygiene practices.[4,5] Dentures made from synthetic polymers like polymethylmethacrylate are micro-porous in nature and, therefore, cause Candida to easily adhere and colonize. In addition, several host factors such as diet, immune competence, surface roughness, denture cleansers, cleaning methods, saliva with food particles, age, hormonal imbalance and other predisposing factors facilitate the adhesion and colonization on the dentures surface.[6] Plaque, stain, and calculus accumulate on the dentures in a manner similar to natural teeth.[7] The subsequent proliferation of oral microbes and the formation of plaque on the nonshading surface may initiate pathogenesis from the oral to the systemic front. A less disturbed and relatively stagnant posterior and the interior region of denture is found to be contaminated by a load of oral microbes.[8]

Among Candida species that colonize the surface in the oral cavity, Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis, Candida stellatoidae, Candida krusei and Candida kefyr are reported to be associated with both clinical and nonclinical conditions.[4,5,6,7,8] C. albicans is frequently isolated from the normal oral cavity; however only a few are associated with Candidiasis.

Adherence, a virulence trait of Candida enables it to resist the flushing action of saliva, and the resultant colonization is, followed by infection. Literature shows normal denture flora is less studied than the flora of denture induced pathologies. Hence, this is an effort to contribute toward the denture microflora and to look at the prevalence of Candida species from healthy denture and nondenture wearers (NDWs). The results generated were correlated with age and oral hygiene of the subjects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

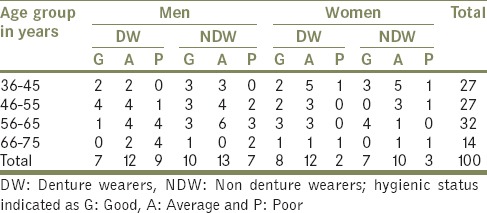

The study was carried out on 100 subjects aged between 35 and 80 years. It included a group comprising 50 denture wearers (DW) and 50 NDWs. The DW group comprised 28 men and 22 women with a mean age of 54.38 ± 10.31, who had been using removable complete dentures for a minimum of 1-year. The NDW comprised 31 men and 20 women with mean age 51.92 ± 9.2. The age, denture hygiene and denture wearing status of subjects are given in listed in Table 1. The DW attended the dental clinics of the Prosthodontic Department of K.V.G. Dental College; Sullia were considered for the study. Prosthodontists examined the patients for any oral infections. DWs having any Candidial infection were rejected from the study. NDW were healthy individuals with no systemic disease and no clinical signs of oral infection including Candidiasis. All the individuals under study, who received or were currently on antibiotics, antifungal, steroids or immunosuppressive drugs in the past 6 months, were excluded from the study. A questionnaire was prepared to document the subject's profile. Denture and oral hygiene were graded as good, average and poor based on the prosthodontist's report. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects of this study.

Table 1.

Age, hygiene and denture wearing status among men and women

The most of the denture plaque occurs on the denture-base of the upper denture[8], and hence the tissue contact surface of the upper denture was considered for isolation of Candida in our study. For NDW sample collection was from their palatal mucosa and in DW the samples were collected from the tissue bearing area of the upper denture by scraping it with a sterile swab. The swabs were processed for microbiological examination by immersing it in 5 ml of physiological saline. This was vortexed to disperse the adhering bacteria. A loopful of the suspension was plated on Sabouraud's dextrose (SD) agar (Hi Media, Mumbai, India) containing gentamycin (2 mg/dL) and chloramphenicol (5 mg/dL) and incubated for 48 h at 37°C. Typical colonies suggestive of Candida spp. were picked up and stained by Gram's and the lactophenol blue to observe their morphology and subjected to a battery of biochemical test. Identification of Candida was done by studying surface growth in SD broth, carbohydrate assimilation test, carbohydrate fermentation test, serum germ tube test and studying chlamydospores formation on Corn meal agar. Results obtained analyzed using Student's t-test and Chi-square test.

RESULTS

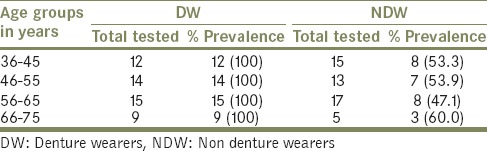

Candida species isolated and identified from both DW and NDW are listed in Table 2. There was a significant difference in the numbers of Candida species isolated from DW and NDW [Table 3]. Candida spp. was isolated from DW among all age groups, while only 52% of the NDW showed the presence of Candida species. Among NDW, although a higher proportion (60%) of Candida was isolated from subjects between the age group 66-75, there existed no significant difference between age and prevalence of Candida species.

Table 2.

Distribution of Candida isolates in denture and nondenture wearers

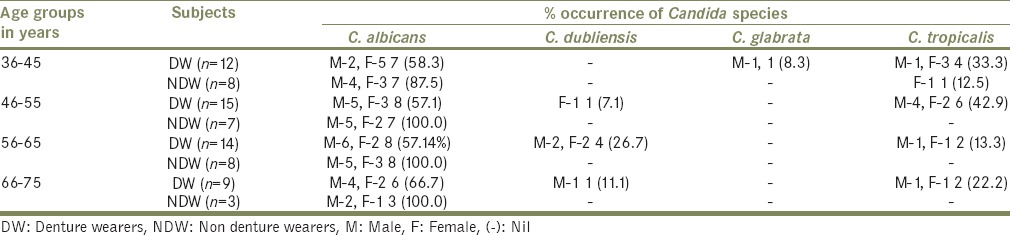

Table 3.

Distribution of different Candida spp. among denture and nondenture wearers

Denture wearers harbored a mixed species of Candida which was predominantly C. albicans (58%), followed by C. tropicalis (28%), Candida dubliensis (12%) and C. glabrata (2%) wherein all the age groups showed more than 2 different Candida species. In contrast, among NDW, C. albicans was observed to be the dominant (96.2%) species. Except for one individual (in the age group 36–45), who was positive for C. tropicalis, rest all other age groups were negative for both C. tropicalis and C. dubliensis [Table 3].

Prevalence of Candida spp. was higher in males than females. Among male DWs prevalence of C. albicans increased with age with, highest seen in the age group 66–75 (66.7%) and lowest between 36 and 45 (58.3%), while in female DWs, it was highest in the age group 36–45 (41.7%) and lowest in subjects of the group 66–75 (22.2%). Oral hygiene had an influence on the prevalence of Candida spp., in both the groups. Males had poor oral hygiene than females.

DISCUSSION

Insertions of the denture bring about changes in the physiology and normal flora of the palate. Tissue contact surface of the denture is less disturbed and enhances the easy colonization of microbes, especially acidogenic bacteria and Candida.[9] Studies on Candida prevalence and colonization with respect to gender and age among DWs with stomatitis have been reported, however, the prevalence and colonization by Candida in healthy denture and NDWs is less studied. This study gives an insight about carriers’ status of the Candida species. There are studies which demonstrated that denture insertion induces plaque formation favoring the increased population of potentially pathogenic bacteria and Candida spp.[10,11] The higher prevalence of different Candida species in DWs in contrast to NDW, confirms the reports on denture insertion inducing plaque formation.

Candida spp. readily forms a biofilm on denture acrylic surfaces and, therefore, are isolated more frequently from denture plaque than from dental plaque.[12] In this study, there was a significant difference (P < 0.001) in the prevalence of Candida spp. between DW and NDW.

Our findings on the prevalence and species diversity of Candida from denture samples are similar to the study of Davenport[13] who demonstrated higher level of Candida spp. on the denture surface compared to the palatal mucosa.

Candida colonization increases with increasing age irrespective of the denture wearing status.[14] Denture insertion accelerates the colonization and biofilm formation. In our study, this trend was seen only in male DWs. The higher prevalence among male DWs in both the groups differ from the study of Arenforf and Walker[2] where females were the frequent carriers of Candida species rather than males. Aging causes a progressive increase in Candida counts in the oral cavity[15] with higher counts being observed among elderly DWs than NDWs.[6]

The predominant Candida spp. among DWs was C. albicans followed by C. tropicalis and C. dubliensis. This is different from an earlier report[16] wherein C. glabrata was the dominant species. Candida was isolated more in males than females in both DW and NDW. Morphological similarities pose a problem in the identification of some species such as C. albicans and C. dubliensis.[17] The isolation of C. dubliensis from denture stomatitis and HIV patients has been reported.[18] In contrast to this, we isolated six C. dubliensis from healthy DWs with no signs of candidiasis. C. dubliensis were confirmed by the abundant chlamydospores formed on corn meal agar and positive germ tube test. To get rid of the denture plaque associated infections and denture malodor, adequate cleaning of the dentures and vigilance is needed.

Thus, it can be concluded that DWs though apparently free from diseases they are asymptomatic carriers of multispecies Candida. This may expose themselves to the risk of candidiasis with predisposing factors like old age and decreasing immunity. Compared to NDWs, diverse and increased prevalence of Candida species is seen among DWs, who are prone to get candidiasis and denture stomatitis. Therefore adequate and regular cleaning of the denture is a prerequisite for better oral and systemic health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The first author would like to thank the HOD and staff of the Department of Prosthodontic, K. V. G. Dental College, Sullia, Karnataka, for their help in the collection of samples. The advice and support rendered by Prof. Subbannayya Kotigadde, Department of Microbiology, and K.V.G. Medical College is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Department of Microbiology, College of Fisheries, Karnataka Veterinary and Fisheries Sciences University, Mangalore - 575 002, India

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aas JA, Paster BJ, Stokes LN, Olsen I, Dewhirst FE. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5721–32. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5721-5732.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ribeiro DG, Pavarina AC, Dovigo LN, Machado AL, Giampaolo ET, Vergani CE. Prevalence of Candida spp. associated with bacteria species on complete dentures. Gerodontology. 2012;29:203–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2011.00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zegarelli DJ. Fungal infections of the oral cavity. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1993;26:1069–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koch C, Bürgers R, Hahnel S. Candida albicans adherence and proliferation on the surface of denture base materials. Gerodontology. 2013;30:309–13. doi: 10.1111/ger.12056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Figueiral MH, Azul A, Pinto E, Fonseca PA, Branco FM, Scully C. Denture-related stomatitis: Identification of aetiological and predisposing factors-A large cohort. J Oral Rehabil. 2007;34:448–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2007.01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Budtz-Jörgensen E. Etiology, pathogenesis, therapy, and prophylaxis of oral yeast infections. Acta Odontol Scand. 1990;48:61–9. doi: 10.3109/00016359009012735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coulthwaite L, Verran J. Potential pathogenic aspects of denture plaque. Br J Biomed Sci. 2007;64:180–9. doi: 10.1080/09674845.2007.11732784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glass RT, Belobraydic KA. Dilemma of denture contamination. J Okla Dent Assoc. 1990;81:30–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verran J. Preliminary studies on denture plaque microbiology and acidogenicity. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 1988;1:51–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coulter WA, Strawbridge JL, Clifford T. Denture induced changes in palatal plaque microflora. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 1990;3:77–85. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sumi Y, Kagami H, Ohtsuka Y, Kakinoki Y, Haruguchi Y, Miyamoto H. High correlation between the bacterial species in denture plaque and pharyngeal microflora. Gerodontology. 2003;20:84–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2003.00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verran J, Maryan CJ. Retention of Candida albicans on acrylic resin and silicone of different surface topography. J Prosthet Dent. 1997;77:535–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(97)70148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davenport JC. The oral distribution of Candida in denture stomatitis. Br Dent J. 1970;129:151–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4802540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaremba ML, Daniluk T, Rozkiewicz D, Cylwik-Rokicka D, Kierklo A, Tokajuk G, et al. Incidence rate of Candida species in the oral cavity of middle-aged and elderly subjects. Adv Med Sci. 2006;51(Suppl 1):233–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lockhart SR, Joly S, Vargas K, Swails-Wenger J, Enger L, Soll DR. Natural defenses against Candida colonization breakdown in the oral cavities of the elderly. J Dent Res. 1999;78:857–68. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780040601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanden Abbeele A, de Meel H, Ahariz M, Perraudin JP, Beyer I, Courtois P. Denture contamination by yeasts in the elderly. Gerodontology. 2008;25:222–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2007.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giammanco GM, Pizzo G, Pecorella S, Distefano S, Pecoraro V, Milici ME. Identification of Candida dubliniensis among oral yeast isolates from an Italian population of human immunodeficiency virus-infected (HIV) subjects. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2002;17:89–94. doi: 10.1046/j.0902-0055.2001.00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faggi E, Pini G, Campisi E, Martinelli C, Difonzo E. Detection of Candida dubliniensis in oropharyngeal samples from human immunodeficiency virus infected and non-infected patients and in a yeast culture collection. Mycoses. 2005;48:211–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2005.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]