Abstract

The all‐phosphorus analogue of benzene, stabilized as middle deck in triple‐decker complexes, is a promising building block for the formation of graphene‐like sheet structures. The reaction of [(CpMo)2(μ,η6:η6‐P6)] (1) with CuX (X=Br, I) leads to self‐assembly into unprecedented 2D networks of [{(CpMo)2P6}(CuBr)4]n (2) and [{(CpMo)2P6}(CuI)2]n (3). X‐ray structural analyses show a unique deformation of the previously planar cyclo‐P6 ligand. This includes bending of one P atom in an envelope conformation as well as a bisallylic distortion. Despite this, 2 and 3 form planar layers. Both polymers were furthermore analyzed by 31P{1H} magic angle spinning (MAS) NMR spectroscopy, revealing signals corresponding to six non‐equivalent phosphorus sites. A peak assignment is achieved by 2D correlation spectra as well as by DFT chemical shift computations.

Keywords: coordination polymers, copper, hexaphosphabenzene, molybdenum, triple-decker complexes

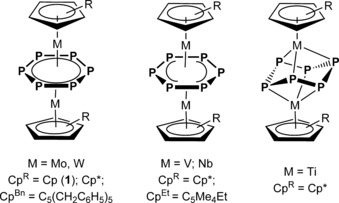

Tailored syntheses of the inorganic analogues of organic molecules, is a fascinating area of fundamental research. Following the so‐called isolobal principle,1 substitution of methine moieties by phosphorus atoms appears quite promising. In fact, 2016 marks the 50th anniversary of the first successful synthesis of a phosphabenzene in which one CH unit is replaced by a P atom,2 which set the stage for the ultimate goal, namely the preparation of carbon‐free hexaphosphabenzene. Since then, many theoretical studies with respect to its aromaticity were reported that outlined the instability of a free cyclo‐P6 unit.3 Nevertheless, its detection in an inert stabilizing matrix at low temperature might be feasible such that the challenge remains. A synthetic approach demonstrated by the Scherer group is the stabilization of the P6 ring by coordination to transition metals, thus affording a triple‐decker complex [(Cp*Mo)2(μ,η6:η6‐P6)] (Cp*=η5‐C5Me5) bearing a planar P6 middle deck for the first time (Figure 1).4 Triple‐decker complexes containing the cyclo‐P6 unit could also be obtained for vanadium,5 tungsten,5 or niobium.6 Quite recently, the sandwich complex [(CpMo)2(μ,η6:η6‐P6)] (1) with the parent Cp ligands was synthesized and characterized.7 In the case of the Mo and W complexes, the cyclo‐P6 ring has a perfect D 6h symmetry, whereas V and Nb derivatives exhibit a slight bisallylic distortion.6a It should be noted that the middle deck in [(Cp*Ti)2(μ,η3:η3‐P6)] has a chair conformation (Figure 1).8

Figure 1.

Triple‐decker complexes containing a cyclo‐P6 middle deck.

In contrast to benzene, the presence of lone pairs at the phosphorus atoms converts these triple‐decker complexes into excellent building blocks for supramolecular chemistry. Particularly intriguing is the possibility of graphene‐like honeycomb networks resulting from reaction with Lewis acidic metal salts, an unmet challenge to date.

We have applied Lewis acidic coinage metal salts for linkage of unsubstituted Pn complexes9 and also for [(CpRMo)2(μ,η6:η6‐P6)] (CpR=Cp*, CpBn=η5‐C5(CH2C6H5)5).10 For example, the coordination of the bare cations Cu+, Ag+, and Tl+ was studied revealing discrete [M{(Cp*Mo)2(μ,η6:η6‐P6)}2]+ (M=Cu, Ag) units as well as a two‐dimensional coordination network for M=Tl.10a In this structure, the positively charged layers are separated by the weakly coordinating anions [Al{OC(CF3)3}4]−, forming an alternating network of cationic and anionic sheets.

Except for rather weak interactions of the P6 unit with a mercury trimer [(o‐C6F4Hg)3] yielding a super‐sandwich structure,7 the corresponding supramolecular chemistry of 1 utilizing its coordination properties is hitherto unknown.

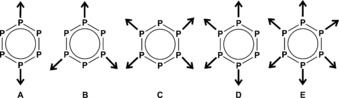

The P6 unit offers competitive coordination sites (Figure 2), which also presents potential problems. A considerable variety of connectivity renders the growth of single crystals suitable for X‐ray analysis challenging. Indeed, twinned or layered crystals may be also encountered but occur in particular in the case of Cp rings. The obtained polymeric products are often insoluble and are sometimes even microcrystalline powders so that X‐ray diffraction analysis is crucial for a determination of the exact coordination pattern. Since modern solid‐state NMR techniques provide complementary information including the number of independent molecules in the unit cell, intermolecular distances or connectivity, the spatial proximity of constituent moieties, and even orientation relations, it is a very powerful tool for structure determination, particularly in case of powdered compounds (“NMR crystallography”).11

Figure 2.

Some possible coordination modes of a cyclo‐P6 ligand.

Herein, we report the coordination properties of the parent triple‐decker complex 1 towards CuX (X=Br, I) revealing unprecedented 2D networks with similarities to graphene‐like monolayers and distortion of the P6 middle deck. All polymers were characterized by X‐ray diffraction analysis as well as 1D 31P{1H} magic‐angle spinning (MAS) NMR spectroscopy where the peak assignment is based on the analysis of 2D 31P‐31P MAS NMR correlation spectra and (split basis set) density functional theory (DFT) 31P chemical shift computations.

When a colorless solution of CuX (X=Br, I) in CH3CN is layered above an orange‐brown solution of 1 in CH2Cl2 or toluene, an immediate color change to gray‐black at the phase boundary occurs. During the diffusion process, a black powder precipitates and small black crystals are formed. The products are insoluble in hexane, toluene, CH2Cl2, CH3CN, or THF, but possess a good solubility in pyridine, though at the cost of some fragmentation of the compounds, as seen by the recorded singlet peak at δ=−351.5 ppm in the corresponding 31P{1H} solution NMR spectra (in [D5]pyridine) of the black microcrystalline solid and precipitate attributed to the starting compound 1.

Therefore, an effort was made to derive suitable crystallization conditions for the coordination products, applying a range of solvent mixtures and dilution conditions (see the Experimental Section).

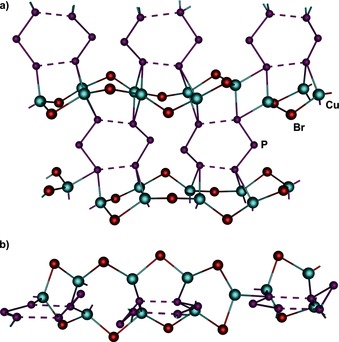

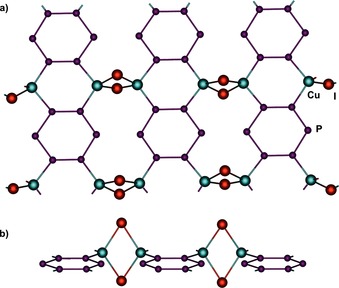

In the presence of CuBr, the polymer [{(CpMo)2(μ,η3:3:1:1:1:1‐P3)(μ,η3:2:1:1:1:1‐P3)}Cu4(μ‐Br)4]n (2) crystallizes as black plates in the centrosymmetric triclinic space group P (no. 2). Its X‐ray structural analysis reveals a two‐dimensional network with a cyclo‐P6 middle deck in a 1,2,4,5‐coordination mode (Figure 2, type C; Figure 3). Each of the four P atoms coordinates two Cu atoms in a η1:η1 fashion (Figure 3 a). These in turn link the triple‐decker complexes by forming {Cu2P2} four‐membered rings. Taking into account the μ‐Br ligands, contorted five‐membered {P2Cu2Br} rings become also visible (Figure 3 a; for bond lengths, see the Supporting Information). A distinctive feature in 2 is the distortion of the cyclo‐P6 middle deck which is no longer planar.

Figure 3.

Section of the 2D polymeric network 2. [CpMo] units and minor disordered fragments are omitted for clarity; a) top view; b) side view.

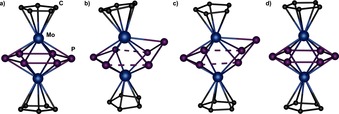

The side view illustrates that one P atom is bent out of the plane by 1.141(3) Å and therefore solely coordinated to one molybdenum atom with a bond length of 2.652(3) Å (Figure 4 b). In comparison to the other Mo−P distances (2.400(2) Å–2.657(3) Å), this bond appears significantly elongated. Furthermore, the P6 ring shows a significant bisallylic distortion where the P3 units are separated by 2.652(3) Å and 2.444(3) Å, respectively. The remaining P−P bond lengths are 2.168(4) Å and 2.162(4) Å for one P3 ligand and 2.138(3) Å and 2.136(5) Å for the other (containing the envelope P atom), thus in between a single and double bond, and even shorter than in complex 1 (P−Paverage 2.177(2) Å).7 The distortion of the whole unit leads the Cp ligands to be inclined by 9.26° compared to a parallel arrangement in 1.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the distortion of the P6 ring in a) 1; b) 2; c) 3 a; d) 3 b.

Notably, the geometry found is unique for P6 middle decks, which most likely results from the coordination to Cu. Though the vanadium5 and niobium6 derivatives as well as the one‐electron oxidation product of 1 10a also show bis‐allylic distortion, the P6‐ring remains planar in all examples (Figure 1). Furthermore, no chair‐like conformation is present in 2, hampering comparison to the titanium complex (Figure 4). Despite the distorted P6‐ring, compound 2 forms planar layers (Figure 5).

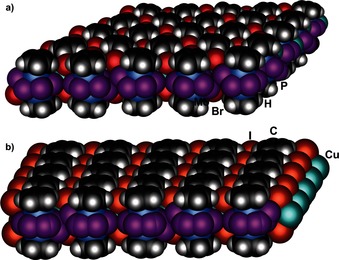

Figure 5.

Space‐filling representation of a section of a) 2 and b) 3 forming a planar layer.

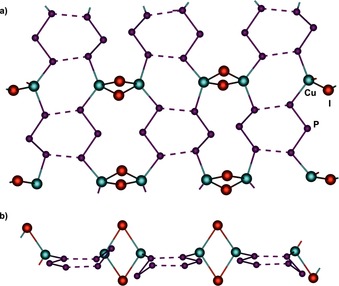

In the presence of CuI, the compound [{(CpMo)2(μ,η3:3:1:1‐P3)(μ,η3:2:1:1‐P3)}0.84{(CpMo)2(μ,η6:6:1:1:1:1‐P6)}0.16Cu2(μ‐I)2]n (3) is obtained, crystallizing as black plates in the monoclinic space group C2/m (no. 12). Its structure is comprised of a two‐dimensional polymer with a 1,2,4,5‐coordination mode of the middle deck (Figure 2, type C; Figure 6, Figure 7), comparable to 2. In this structure, unlike that of the Br derivative, each P atom is bound to one copper atom, which in turn forms {Cu2P4} six‐membered and {Cu(μ‐I)}2 four‐membered rings, resulting in a characteristic tetrahedral environment for Cu (for bond lengths, see the Supporting Information). Hence, the Cu halide framework is much less extended than in 2. The cyclo‐P6 rings, however, prove to be disordered exhibiting two distinct coordination modes: [{(CpMo)2(μ,η3:3:1:1‐P3)(μ,η3:2:1:1‐P3)}Cu2(μ‐I)2]n (3 a; Figure 6) and [{(CpMo)2(μ,η6:6:1:1:1:1‐P6)}Cu2(μ‐I)2] (3 b; Figure 7) with corresponding occupancy factors of 0.84 and 0.16, respectively.

Figure 6.

Section of the 2D polymeric network with all P6 ligands showing the geometry and coordination mode of 3 a (84 %). [CpMo] units are omitted for clarity; a) top view; b) side view.

Figure 7.

Section of the 2D polymeric network with all P6 ligands showing the geometry and coordination mode of 3 b (16 %). [CpMo] units and are omitted for clarity; a) top view; b) side view.

The middle deck in 3 a shows the same bisallylic distortion as in 2 but with more uniform distances of 2.563(8) Å and 2.544(8) Å between the P3 fragments (Figure 4). The bending of one P atom out of the plane by 1.113(9) Å is somewhat less distinctive but in a comparable range as of 2, though the Cp ligands retain their parallel arrangement in 3 a. The bent phosphorus atom is additionally disordered over the mirror plane with an occupancy factor of 0.42 each. The distance between molybdenum and this out‐of‐plane phosphorus atom (2.683(8) Å) is the longest among all of the Mo−P bond lengths (2.434(4) Å–2.598(4) Å), but possible uncertainties caused by the disorder cannot be discounted. Again, the remaining P−P bond lengths (η3:3:1:1‐P3 2.127(7) Å, 2.132(7) Å; η3:2:1:1‐P3 2.151(9), 2.147(10) Å) are shortened compared to those of 1.

Surprisingly, with an occupancy factor of 0.16, the intact cyclo‐P6 middle deck is present (substructure 3 b, Figure 7, Figure 4 d). It is located on a mirror plane and is therefore perfectly planar. The coordination to Cu leads to a shortening of the P−P bond lengths with respect to those of 1, which is consistent with 2 and 3 a and most significant for Pcoord−Pcoord with values of 2.00(3) Å and 2.01(4) Å, respectively (P−Pcoord 2.03(3)–2.132(7) Å).

The question whether the bent (3 a) and planar (3 b) cyclo‐P6 middle decks occur within the same layer or the layers comprising the same middle decks form with different probability cannot be answered solely from structural data. As with 2 absolutely planar sheet‐like structures are also formed in 3 (Figure 5 b).

Compared to the coordination polymer built from [(Cp*Mo)2(μ,η6:η6‐P6)] and Tl[Al{OC(CF3)3}4] that maintains planarity of the middle decks,10 the coordination mode as well as the distortion of the cyclo‐P6 ligand in 2 and 3 are unique.

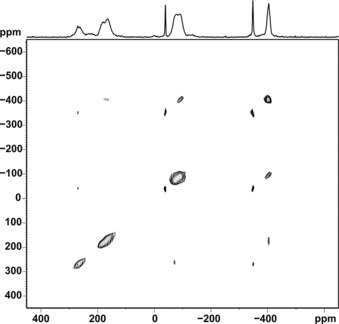

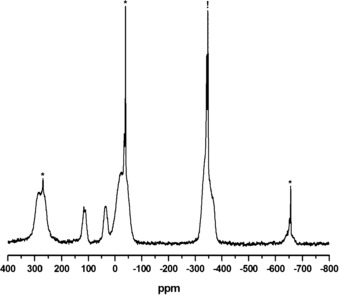

Because the polymer networks are insoluble in common solvents and fragmentation is observed in pyridine, 31P{1H} MAS NMR spectra of both compounds (2 and 3) were recorded. Even though the 31P chemical shifts (with respect to H3PO4) occur over a rather large range of values, the magnitude of the range of observed signals (ca. 700 ppm) is remarkable. To achieve a sufficient spectral resolution while allowing for quantitative interpretation of the acquired spectra, the conflicting demands of the significant 31P chemical shift anisotropy and line‐broadening contributions from 31P–63, 65Cu dipolar couplings have to be considered. Thus, the 31P{1H} MAS NMR spectra of 2 and 3 were recorded at fast MAS and a magnetic field of 4.7 T rather than at 11.7 T.

The 31P{1H} MAS NMR spectrum of 2 (Figure 8) at first glance exhibits four rather broad peaks and a sharp peak at −347.4 ppm with spinning sidebands (marked with asterisks). The latter signal can readily be attributed to the presence of residual 1, whereas assignment of the signals for the P6 unit is not straightforward. The corresponding isotropic chemical shifts however could be unambiguously identified from the diagonal peaks in a 2D 31P–31P correlation spectrum of 2 with radio‐frequency‐driven dipolar recoupling (RFDR) applied during a short mixing time (Figure 9).12

Figure 8.

31P MAS NMR spectrum of 2 (acquired at 81.02 MHz and 25 kHz MAS). A sharp peak (marked with !) at −347.4 ppm indicates residual 1 while the signals marked with asterisks are spinning sidebands.

Figure 9.

2D 31P–31P RFDR MAS NMR spectrum of 2 (acquired at 81.02 MHz and 25 kHz MAS at a short mixing time of 320 μs). The peaks in the diagonal (marked in green) reflect the isotropic chemical shifts of the phosphorus sites that are not readily accessible from the 1D 31P MAS NMR spectrum of 2.

Six independent phosphorus sites were identified in the RFDR spectrum of 2 (Figure 9) with signals at 268.3, 185.6, 164.7, −74.9, −91.4, and −403.8 ppm, respectively, where the subsequent line‐shape analysis revealed a 1:1:1:1:1:1 peak area distribution and an impurity fraction of 5 % (sharp signal of 1). A cutout of 2 (see Figure 10) was subjected to a split basis set for DFT chemical shift computation with PBE1PBE/cc‐pVQZ13 level for 31P and used for assignment. It is apparent that a comparable coordination of the considered phosphorus atoms by copper or molybdenum atoms results in rather similar 31P chemical shifts yielding the following peak assignment [DFT values]: P13 268.3 [337], P15 185.6 [235], P11 164.7 [166], P14 −74.9 [−18], P12 −91.4 [−26], and P16 −403.8 ppm [−480 ppm].10

Figure 10.

Site labeling of the P6 ligands in 2, 3 a, and 3 b as subjected to 31P DFT chemical shift computation.

In contrast, the 31P MAS NMR spectrum of 3 (Figure 11) demonstrates the presence of the different coordination modes of the cyclo‐P6 unit as documented by the larger range of signals compared to 2, which yield Gaussian‐type peaks at 283.4, 270.3, 114.4, 35.9, −22.3, −37.6 ppm as well as −345 and −653 ppm. Though unambiguous spectral fitting could not yet be achieved, in part owing to the presence of residual 1 and further impurities, 31P DFT chemical shift computations at PBE1PBE/cc‐pVQZ level of theory based on representative structure cutouts of 3 a and 3 b (for labeling, see Figure 10) indicated that the constituents of the P6 unit in 3 b resonate between −350 ppm and −520 ppm. Hence, they are significantly shifted towards more negative values [DFT: P2/P7 −353, P1/P8 −394, P5 −455, P6 −519 ppm]. In the case of 3 a, phosphorus sites are computed as: P3 234, P2 234, P8 227, P5 11, P1 −30, and P4 −368 ppm, which is more comparable to those of 2, reflecting a similar distortion of the P6 unit in 3 a (see Figure 4).

Figure 11.

31P MAS NMR spectrum of 3 (acquired at 81.02 MHz and 25 kHz MAS). A sharp peak (marked with !) at −346.7 ppm likely indicates residual 1, while signals marked with asterisks are spinning sidebands; the additional sharp peak at −342.9 ppm may be attributed to a further impurity. The overall signal fraction of the sharp peaks is approximately 12 %.

Nevertheless, further impact of local coordination, including bond lengths, torsion angles, or even the orientation of [CpMo] units on the local electron density distribution at the distinct phosphorus sites in 2 and 3 is evident, rendering 31P MAS NMR a sensitive probe for structure elucidation of such compounds.

In summary, the first coordination polymers 2 and 3 containing the parent triple‐decker complex 1 are obtained by the self‐assembly with CuX (Br, I). Their structures reveal two‐dimensional polymers with the cyclo‐P6 middle deck in a 1,2,4,5‐coordination mode to copper. Resembling graphene‐like sheets, the layers hereby formed are planar. Surprisingly, the coordination profoundly affects the geometry of the P6 unit of 1 as evidenced by a significant bisallylic distortion and unprecedented envelope conformation of one phosphorus atom in both polymers. Owing to insolubility of 2 and 3, they were comprehensively characterized by 1D and 2D 31P{1H} MAS NMR spectroscopy. The obtained signals are spread over a remarkable range of more than 900 ppm and correspond to six independent phosphorus atoms, consistent with the distorted P6 moiety. Furthermore, DFT chemical shift computations allow a reliable assignment of the signals.

Experimental Section

All of the reactions were performed under an inert atmosphere of dry nitrogen or argon with standard vacuum, Schlenk, and glove‐box techniques. Solvents were purified, dried, and degassed prior to use by standard procedures. Complex 1 was synthesized following the reported procedure.7 Commercially available chemicals were used without further purification. Solution NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 300 spectrometer. The corresponding ESI‐MS spectra were acquired on a ThermoQuest Finnigan MAT TSQ 7000 mass spectrometer, whereas elemental analyses were performed on a Vario EL III apparatus.

Synthesis of 2: In a large Schlenk tube, a bright orange‐brown solution of 1 (100 mg, 0.20 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (100 mL) is carefully layered first with a solvent mixture CH2Cl2/CH3CN (2:1, 20 mL), then with a colorless solution of CuBr (186 mg, 1.30 mmol) in CH3CN (50 mL). Already after one day, the formation of small black crystals of 2 at the phase boundary, sometimes in addition to red plates of 1, can be observed. After complete diffusion the mother liquor is decanted, the crystals are washed with CH2Cl2 to remove residues of the starting material 1. Afterwards the crystals are washed with hexane (3×15 mL) and dried in vacuo to yield 105 mg of 2 (0.05 mmol, 53 %). The synthesis of 2 can also be down‐scaled to a few mg of the starting materials and accordingly a few mL of solvents. Crystals suitable for X‐ray structural analysis can be obtained, when a solution of 2 (4 mg, 0.008 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL) is layered first with a solvent mixture CH2Cl2/CH3CN (2:1, 2 mL), afterwards with a solution of CuBr (7 mg, 0.05 mmol) in the same solvent mixture of CH2Cl2/CH3CN (2:1, 5 mL) in a thin Schlenk tube. Analytical data of 2: 1H NMR ([D5]pyridine): δ [ppm]=2.55 (s, (CpMo)2P6); 31P{1H} NMR ([D5]pyridine): δ [ppm]=−351.60 (s, (CpMo)2P6); Positive‐ion ESI‐MS (pyridine): m/z (%)=935.5 [{(CpMo)2P6}Cu3Br2(C5H5N)]+, 899.5 [{(CpMo)2P6}Cu3Br2(CH3CN)]+, 858.5 [{(CpMo)2P6}Cu3Br2]+, 795.6 [{(CpMo)2P6}Cu2Br(C5H5N)]+, 776.9 [{(CpMo)2P6}Cu(C5H5N)2(CH3CN)]+, 729.9 [{(CpMo)2P6}Cu(C5H5N)2]+, 711.9 [{(CpMo)2P6}Cu2Br]+, 649.7 [{(CpMo)2P6}Cu(C5H5N)]+, 508.6 (6) [Cu3Br2(C5H5N)2]+, 364.7 [Cu2Br(C5H5N)2]+, 220.9 (100) [Cu(C5H5N)2]+, 182.9 (60) [Cu(C5H5N)(CH3CN)]+; Negative‐ion ESI‐MS (pyridine): m/z (%)=796.2 (4) [Cu5Br6]−, 654.3 (3) [Cu4Br5]−, 510.4 (4) [Cu3Br4]−, 366.4 (27) [Cu2Br3]−, 222.5 (100) [CuBr2]−; Elemental analysis: Calculated (%) for [{(CpMo)2P6}(CuBr)4] (1082 g mol−1): C 11.10, H 0.93; found: C 11.19, H 0.98.

Synthesis of 3: In a large Schlenk tube, a bright orange‐brown solution of 1 (90 mg, 0.18 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (120 mL) is carefully layered first with a solvent mixture CH2Cl2/CH3CN (2:1, 20 mL), then with a colorless solution of CuI (203 mg, 1.07 mmol) in CH3CN (60 mL). Already after one day, formation of small black crystals of 3 at the phase boundary in addition to red plates of 1 can be observed. After complete diffusion the mother liquor is decanted, the crystals are washed several times with CH2Cl2 to remove 1. When the CH2Cl2 solution is absolutely colorless, the crystals are washed with a toluene/hexane mixture and dried in vacuo to yield 75 mg of 3 (0.084 mmol, 47 %). The synthesis of 3 can also be down‐scaled to a few mg of the starting materials and accordingly a few mL of solvents. Crystals suitable for X‐ray structural analysis can be obtained when a solution of 1 (4 mg, 0.008 mmol) in toluene (5 mL) is layered with a solution of CuI (8 mg, 0.04 mmol) in a solvent mixture of CH2Cl2 (5 mL) and CH3CN (1 mL) in a thin Schlenk tube. Analytical data of 3: 1H NMR ([D5]pyridine): δ [ppm]=2.53 (s, (CpMo)2P6); 31P{1H} NMR ([D5]pyridine): δ [ppm]=−351.51 (s, (CpMo)2P6); Positive‐ion ESI‐MS (pyridine): m/z (%)=952.4 [{(CpMo)2P6}Cu3I2]+, 841.7 [{(CpMo)2P6}Cu2I(C5H5N)]+, 760.9 [{(CpMo)2P6}Cu2I]+, 729.9 [{(CpMo)2P6}Cu(C5H5N)2]+, 649.8 [{(CpMo)2P6}Cu(C5H5N)]+, 410.7 (3) [Cu2I(C5H5N)2]+, 220.9 (100) [Cu(C5H5N)2]+, 182.9 (54) [Cu(C5H5N)(CH3CN)]+; Negative‐ion ESI‐MS (pyridine): m/z (%)=506.5 (5) [Cu2I3]−, 316.6 (100) [CuI2]−, 126.7 (54) [I]−; Elemental analysis: Calculated (%) for [{(CpMo)2P6}(CuI)2] (889 g mol−1): C 13.51, H 1.13; found: C 12.58, H 1.15.

Crystal data for 2:14 C10H10Br4Cu4Mo2P6, M r=1081.68, triclinic, space group P , a=8.1892(4), b=10.3010(5), c=13.5161(6) Å, α=77.009(4), β=86.788(4), γ=67.230(4)°, V=1023.80(9) Å3, Z=2, D calcd=3.509 g cm−3, black plate 0.28×0.07×0.01 mm; Mo Kα radiation, T=123.0(2) K, 13 687 measured, 8496 independent, 6645 observed reflections R int=0.060, μ=13.54 mm−1, refinement (on F 2) with SHELX2014,15 254 parameters, 92 restraints, R 1=0.060 (I>2σ), wR 2=0.165 (all data), GooF=1.04, max/min residual electron density 1.92 and −2.60 e A−3.

Crystal data for 3:14 C10H10Cu2I2Mo2P6, M r=888.76, monoclinic, space group C2/m, a=10.3181(5), b=18.5529(12), c=10.3364(5) Å, β=92.952(5)°, V=1976.08(19) Å3, Z=4, D calcd=2.987 g cm−3, black plate 0.13×0.06×0.10 mm; Cu Kα radiation, T=123.0(2) K, 5332 measured, 1968 independent, 1471 observed reflections, R int=0.073, μ=41.72 mm−1, refinement (on F 2) with SHELX2014,15 124 parameters, 1 restraint, R 1=0.068 (I>2σ), wR 2=0.182 (all data), GooF=1.00, max/min residual electron density 3.25 and −2.06 e A−3.

The 31P{1H} MAS NMR spectra of 2 and 3 were recorded at 4.7 T (31P resonance at 81.02 MHz) and 25 kHz MAS using a Bruker Avance III 200 spectrometer and a Bruker 2.5 mm MAS NMR probe accumulating 2048 scans at a relaxation delay of 90 s and SPINAL64 high power proton decoupling. All pulse lengths were adjusted with respect to a radio‐frequency field strength of 100 kHz (that is, π/2 pulses of 2.5 μs). To avoid severe baseline distortions, the rotor‐synchronized Hahn spin echo sequence was applied (with echo delays of a rotor period (τR=40 μs), corrected for finite pulse durations). The signal (FID of 32k points) was sampled with a dwell time of 0.5 μs and zero‐filled to 128k points prior to processing. Spectral fitting was performed with DMFit.16 All DFT PBE1PBE computations (with 6–311G(d,p) (for H, C, O), cc‐pVQZ (for P), LANL2DZ (for Mo, Cu, Br, I) were done as implemented in the Gaussian 09 software package.17 The obtained 31P chemical shielding σ was “translated” into chemical shifts δ with respect to H3PO4 [δ standard=0 ppm; σ standard(cc‐pVQZ)=349.5809 ppm] using the expression δ sample=σ sample−σ standard+δ standard.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

C.H. is grateful for a PhD fellowship of the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie. The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft supported this work. The European Research Council (ERC) is acknowledged for the support in the SELFPHOS AdG‐2013‐339072 project. G.B. appreciates access to WWU‐PALMA, the High Performance Computing facilities, kindly provided by Prof. A. Heuer (University of Münster).

C. Heindl, E. V. Peresypkina, D. Lüdeker, G. Brunklaus, A. V. Virovets, M. Scheer, Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 2599.

References

- 1. Hoffmann R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012, 124, 10056–10059. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Märkl G., Angew. Chem. 1966, 78, 907–908. [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Minh T. N., Hegarty A. F., J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1986, 383–385; [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Nagase S., Ito K., Chem. Phys. Lett. 1986, 126, 43–47; [Google Scholar]

- 3c. Warren D. S., Gimarc B. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 5378–5385; [Google Scholar]

- 3d. Schleyer P. v. R., Jiao H., Eikema Hommes N. J. R. van, Malkin V. G., Malkina O., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 12669–12670; [Google Scholar]

- 3e. Sakai S., J. Phys. Chem. A 2002, 106, 10370–10373; [Google Scholar]

- 3f. Engelberts J. J., Havenith R. W. A., Van Lenthe J. H., Jenneskens L. W., Fowler P. W., Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 5266–5272; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3g. Pierrefixe S. C. A. H., Bickelhaupt F. M., Aust. J. Chem. 2008, 61, 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scherer O. J., Sitzmann H., Wolmershäuser G., Angew. Chem. 1985, 97, 358–359. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scherer O. J., Schwalb J., Swarowsky H., Wolmershaeuser G., Kaim W., Gross R., Chem. Ber. 1988, 121, 443–449. [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Scherer O. J., Vondung J., Wolmershaeuser G., Angew. Chem. 1989, 101, 1395–1397; [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Reddy A. C., Jemmis E. D., Scherer O. J., Winter R., Heckmann G., Wolmershaeuser G., Organometallics 1992, 11, 3894–3900; for a triphosphaallylic ligand on Ir cf.: [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Mirabello V., Caporali M., Gonsalvi L., Manca G., Ienco A., Peruzzini M., Chem. Asian J. 2013, 8, 3177–3184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fleischmann M., Heindl C., Seidl M., Balázs G., Virovets A. V., Peresypkina E. V., Tsunoda M., Gabbaï F. P., Scheer M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 9918–9921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scherer O. J., Swarowsky H., Wolmershäuser G., Kaim W., Kohlmann S., Angew. Chem. 1987, 99, 1178–1179. [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a. Dielmann F., Heindl C., Hastreiter F., Peresypkina E. V., Virovets A. V., Gschwind R. M., Scheer M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 13605–13608; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 13823–13827; [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Johnson B. P., Dielmann F., Balazs G., Sierka M., Scheer M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 2473–2475; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2006, 118, 2533–2536; [Google Scholar]

- 9c. Scheer M., Gregoriades L., Bai J., Sierka M., Brunklaus G., Eckert H., Chem. Eur. J. 2005, 11, 2163–2169; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9d. Bai J., Virovets A. V., Scheer M., Science 2003, 300, 781–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Fleischmann M., Dielmann F., Gregoriades L. J., Peresypkina E. V., Virovets A. V., Huber S., Timoshkin A. Y., Balazs G., Scheer M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 13110–13115; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 13303–13308; [Google Scholar]

- 10b.F. Dielmann, Dissertation thesis, (Universität Regensburg), 2011;

- 10c.L. Gregoriades, Dissertation thesis, (Universität Regensburg), 2006.

- 11.

- 11a. Lüdeker D., Brunklaus G., Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 2015, 65, 29–40; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Wiegand T., Lüdeker D., Brunklaus G., Bussmann K., Kehr G., Erker G., Eckert H., Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 12639–12647; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11c. Khan M., Enkelmann V., Brunklaus G., J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 2261–2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bennett A. E., Rienstra C. M., Griffiths J. M., Zhen W., Lansbury P. T., Griffin R. G., J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 108, 9463–9479. [Google Scholar]

- 13.

- 13a. Adamo C., Barone V., J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6169; [Google Scholar]

- 13b. Woon D. E., Dunning T. H., J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 1358–1371. [Google Scholar]

- 14. CCDC 1435940 (2) and 1435941 (3) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre.

- 15. Sheldrick G. M., Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Massiot D., Fayon F., Capron M., King I., Le Calvé S., Alonso B., Durand J. O., Bujoli B., Gan Z., Hoatson G., Magn. Reson. Chem. 2002, 40, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaussian 09, Revision A.02., M. J. Frisch, G. W. Trucks, H. B. Schlegel, G. E. Scuseria, M. A. Robb, J. R. Cheeseman, G. Scalmani, V. Barone, B. Mennucci, G. A. Petersson, H. Nakatsuji, M. Caricato, X. Li, H. P. Hratchian, A. F. Izmaylov, J. Bloino, G. Zheng, J. L. Sonnenberg, M. Hada, M. Ehara, K. Toyota, R. Fukuda, J. Hasegawa, M. Ishida, T. Nakajima, Y. Honda, O. Kitao, H. Nakai, T. Vreven, J. A. Montgomery, Jr., J. E. Peralta, F. Ogliaro, M. Bearpark, J. J. Heyd, E. Brothers, K. N. Kudin, V. N. Staroverov, R. Kobayashi, J. Normand, K. Raghavachari, A. Rendell, J. C. Burant, S. S. Iyengar, J. Tomasi, M. Cossi, N. Rega, J. M. Millam, M. Klene, J. E. Knox, J. B. Cross, V. Bakken, C. Adamo, J. Jaramillo, R. Gomperts, R. E. Stratmann, O. Yazyev, A. J. Austin, R. Cammi, C. Pomelli, J. W. Ochterski, R. L. Martin, K. Morokuma, V. G. Zakrzewski, G. A. Voth, P. Salvador, J. J. Dannenberg, S. Dapprich, A. D. Daniels, O. Farkas, J. B. Foresman, J. V. Ortiz, J. Cioslowski, D. J. Fox, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, (2009).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary