Abstract

Purpose:

This study compared the flow rate and pH of resting (unstimulated) and stimulated whole saliva before and after complete denture placement in different age groups.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty healthy, non-medicated edentulous individuals of different age groups requiring complete denture prostheses were selected from the outpatient department. The resting (unstimulated) and stimulated whole saliva and pH were measured at three stages i.e.,

-

i)

Before complete denture placement;

-

ii)

Immediately after complete denture placement; and

-

iii)

After 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement.

Saliva production was stimulated by chewing paraffin wax. pH was determined by using a digital pH meter.

Results:

Statistically significant differences were seen in resting(unstimulated) and stimulated whole salivary flow rate and pH obtained before, immediately after, and after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement. No statistically significant differences were found between the different age groups in resting (unstimulated) as well as stimulated whole salivary flow rate and pH.

Conclusion:

Stimulated whole salivary flow rates and pH were significantly higher than resting (unstimulated) whole salivary flow rates and pH obtained before, immediately after, and after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement. No age related variations in whole salivary flow rate and pH were observed in healthy, non-medicated individuals.

Clinical Implications:

The assessment of salivary flow rate, pH in different age groups is of prognostic value, which is an important aspect to be considered in the practice of removable prosthodontics.

Key Words: pH, resting whole saliva, salivary flow rate, stimulated whole saliva, xerostomia

INTRODUCTION

Saliva plays a major role in local and systemic defense of the oral cavity, the oropharyngeal region, and the upper gastrointestinal tract.[1] Saliva plays an important role in the maintenance of oral health by exhibiting multiple host defense functions.[2] It fosters and protects the integrity of the soft and hard oral tissues and supports important oral functions.[3]

Saliva is the most valuable oral fluid, one of the most important factors regulating oral health.[4] It is an essential component required for maintenance of the ecologic balance in the oral cavity.[5] Saliva contributes to the maintenance of oro-esophageal, mucosal integrity by lubrication, hydration, clearance, buffering as well as repair.[6] Saliva also performs several important functions such as mineralization, facilitating taste, tissue coating, and antimicrobial activity.[7]

A wealth of evidence suggests that saliva plays a profound role in the maintenance of oral health in the denture wearing patient. Indeed, the presence of a thin salivary film layer is essential for the comfort of the mucosa beneath a denture base and for denture retention. The importance of this film is evident from the multitude of problems associated with denture wear in the xerostomic patient.[8]

Saliva is a unique fluid and interest in it as a diagnostic medium has advanced exponentially in the last 15 years.[9] Saliva provides an easily available, noninvasive diagnostic medium for a rapidly widening range of diseases and clinical situations. Historically, this diagnostic value may have been recognized first by the ancient judicial community who employed salivary flow (or its absence) as the basis for a primitive lie detector test. The accused was given a handful of dry rice. If anxiety (and presumably guilt) so inhibited salivation that he or she could not form an adequate bolus to chew and swallow, than off with their head. In more recent times, where the vagaries of the secretory motor system have been replaced by those of the court system, saliva found its widest use at the race track where the saliva test for drugs became the determinant of a fixed horse race. It is interesting to note that both the ancient and modern use of saliva are different forms of lie detection.[10]

Recently, saliva is a promising option for diagnosing certain disorders and monitoring the evolution of certain pathologies or the dosages of medicines or drugs.[11] Quantitative, multianalyte biochemical assays housed with a compact, easy instrumentation improve the prospects for routine use of biochemical markers to augment clinically observed symptoms, disease progression, and near continuous assessment of therapeutic efficacy. A new microfluidic method facilitates hands-free saliva analysis.[12] There is an increasing interest in using micro-RNAs of saliva as biomarkers in autoimmune disease.[13] Saliva has also been used for identification of cytomegalovirus by means of polymerase chain reaction.[14]

Salivary defense properties reside principally in saliva flow rate, pH, and buffer capacity.[15] Healthy flow of saliva is deemed critical for the maintenance of both oral and general health factors that affect the development, function, and state of differentiation of salivary gland cells would have an effect on the health and well-being of the whole organism.[16]

Many workers earlier have studied saliva as a medium, have had concentrated on salivary flow rate and pH individually and their relevance in particular in dentate patients. Hence, an in vivo study was planned from a comprehensive perspective to assess resting (unstimulated) and stimulated whole salivary flow rate and their pH and to correlate them before and after the complete denture placement in different age groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The participants for this study were 50 edentulous individuals aged from 30 to 76 years, requiring complete denture prostheses, selected from the Department of Prosthodontics, including Crown and Bridge and Implantology, Bapuji Dental College and Hospital, Davangere, Karnataka, India.

Each patient was given a detailed oral description of the nature, purpose, and benefits of the proposed treatment procedure and was required to sign a consent-to-treat agreement. Ethical clearance certificate was obtained from Chairman, Ethical Committee.

Edentulous healthy, nonmedicated individuals without any systemic diseases, the habit of smoking and/or chewing tobacco who required complete denture prostheses having no previous experience of wearing complete dentures were included for this study.

The participants were divided into three groups:

Group 1: Individuals aged ≤45 years (n = 15)

Group 2: Individuals aged between 46 and 60 years (n = 17)

Group 3: Individuals aged 61 years and above (n = 18).

Materials and armamentarium used

Materials: [Figure 1]

Figure 1.

Materials used in this study (distilled water, paraffin wax, and CDTA)

Distilled water

Paraffin wax (Qualigens Fine Chemicals, Product No. 19235, Batch No. 2220 6303 SL, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India)

CDTA (Loba Chemicals, No. 3215, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India).

Armamentarium: [Figure 2]

Figure 2.

Armamentarium used in this study (disposable glass, glass funnel, and graduated measuring jar)

Disposable glass

Glass funnel (Borosil-India)

Graduated measuring jar (Borosil-India)

Stopwatch (Diamond Stop Watch, Model 546244, Shanghai, China)

Digital pH meter (Hanna Instruments, Model R10282, Portugal).

The procedure selected for this study was spitting method for collecting resting (unstimulated) and stimulated whole saliva. The participants were asked to chew paraffin wax (mechanical method) for stimulating whole saliva [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

The procedure for spitting method of collecting whole saliva

Whole saliva was collected under clinical conditions between 09:00 and 11:00 h. The participants were instructed not to eat or drink for 2 h preceding the experiment. They were seated comfortably on the dental chair, with eyes open and head tilted forward.

The participants were asked to rinse their mouths for 5 s with 10 mL distilled water. Following the spitting out of the water and initial swallow, whole saliva was collected by spitting into a graduated measuring jar every 30 s.

The experiment was carried out until 5 mL of whole saliva was collected. Collection times were recorded using stopwatch.

The flow rates of whole saliva and pH were measured at three different stages.

Resting (unstimulated) and stimulated whole saliva and pH before complete denture placement;

Resting (unstimulated) and stimulated whole saliva and pH immediately after complete denture placement; and

Resting (unstimulated) and stimulated whole saliva and pH after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement.

Flow rate was calculated as collected volume/collection time. pH was determined using a digital pH meter (Hanna Instruments, Model R10282, Portugal). The pH meter was calibrated using CDTA (Loba Chemie, No. 3215, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India). The accuracy of the pH meter was checked at regular intervals to ensure that the readings were correct [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

pH determination using digital pH meter

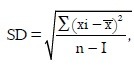

Statistical method employed

Intra and inter group changes were compared by paired t-test

A P < 0.05 was considered for statistical significance

Descriptive statistics are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD)

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for age group comparison.

Formulae used for analysis

Mean,  , I=1, 2, n

, I=1, 2, n

Variance=SD2

Variance=SD2

Standard error, SE=SD/

Paried t-test,

One-way ANOVA,

RESULTS

Individual data obtained with 50 study subjects are shown in Master Graphs 1–3, respectively.

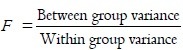

Graph 1.

The mean flow rates (mL/min) of whole saliva at the age group of ≤45 years that is, Group 1 (n = 15)

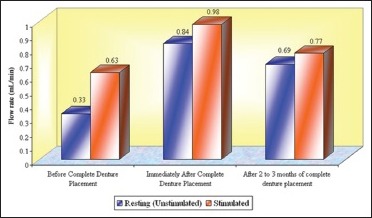

Graph 3.

The mean flow rates (mL/min) of whole saliva at the age group of 61 years and above that is, Group 3 (n = 18)

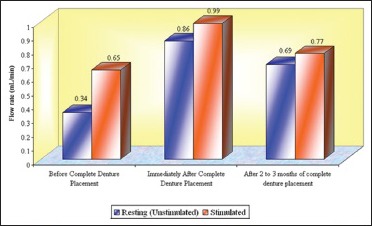

Graph 2.

The mean flow rates (mL/min) of whole saliva at the groups between 46 and 60 years that is, Group 2 (n = 17)

The data were analyzed using the paired comparison t-test. Age group comparison was made using ANOVA [Tables 1–6 and Graphs 1–8].

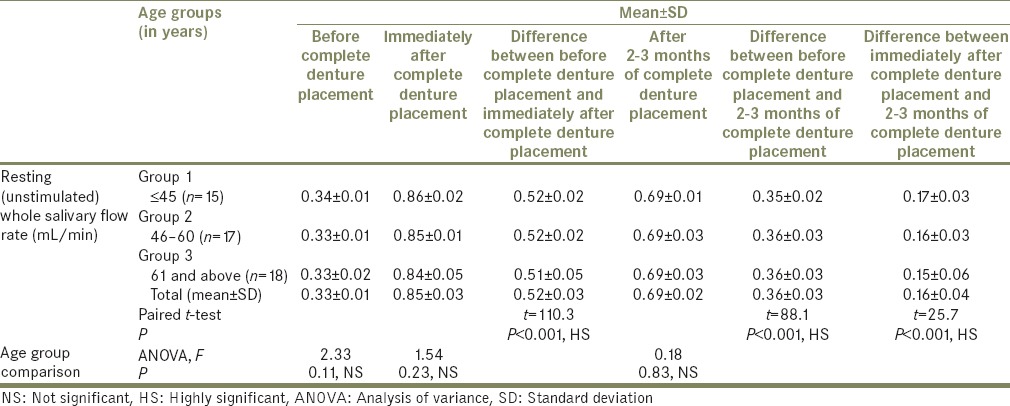

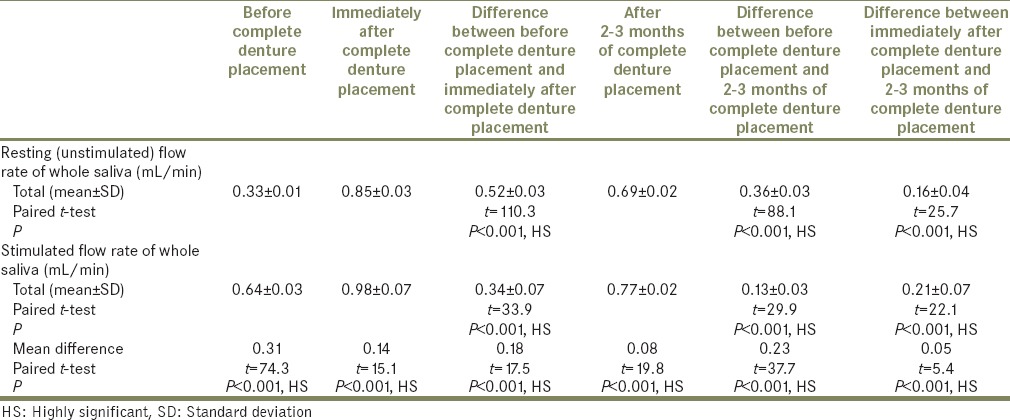

Table 1.

Mean, SD, total mean±SD, ANOVA, paired t-test values, and P values for resting (unstimulated) whole salivary flow rate (mL/min) at different age groups that is., Groups 1, 2, and 3 (n=50) before, immediately after, and after 2-3 months of complete denture placement

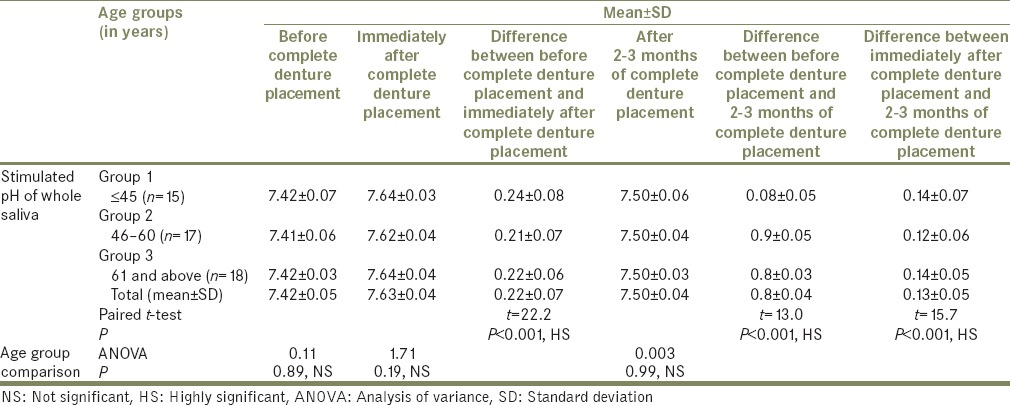

Table 6.

Total mean, SD, mean difference, paired t-test values, and P values for difference between pH of resting (unstimulated) whole saliva and stimulated whole saliva, before, immediately after, and after 2-3 months of complete denture placement

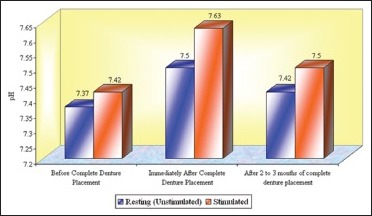

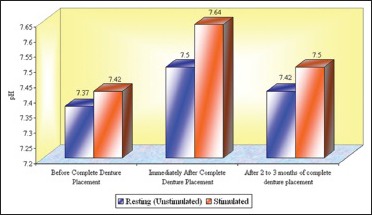

Graph 8.

Total mean pH of whole saliva in different age groups that is, Groups 1, 2, and 3 (n = 50)

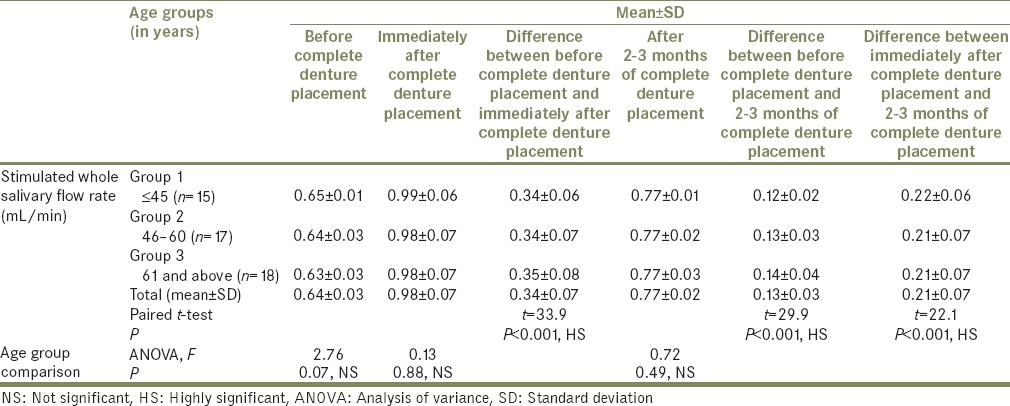

Table 2.

Mean, SD, total mean±SD, ANOVA, paired t-test values, and P values for stimulated whole salivary flow rate (mL/min) at different age groups that is, Groups 1, 2, and 3 (n=50) before, immediately after, and after 2-3 months of complete denture placement

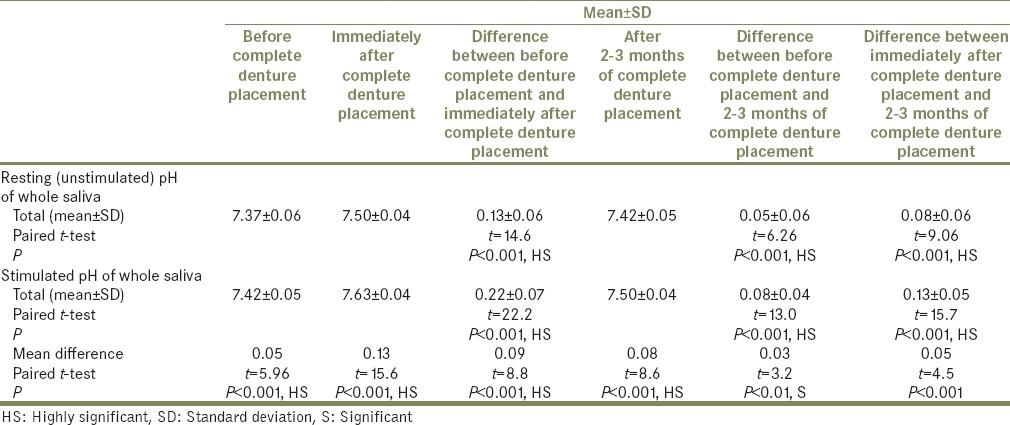

Table 3.

Total mean, SD, mean difference, paired t-test values, and P values for differences between resting (unstimulated) and stimulated whole salivary flow rate (mL/min) before, immediately after, and after 2-3 months of complete denture placement

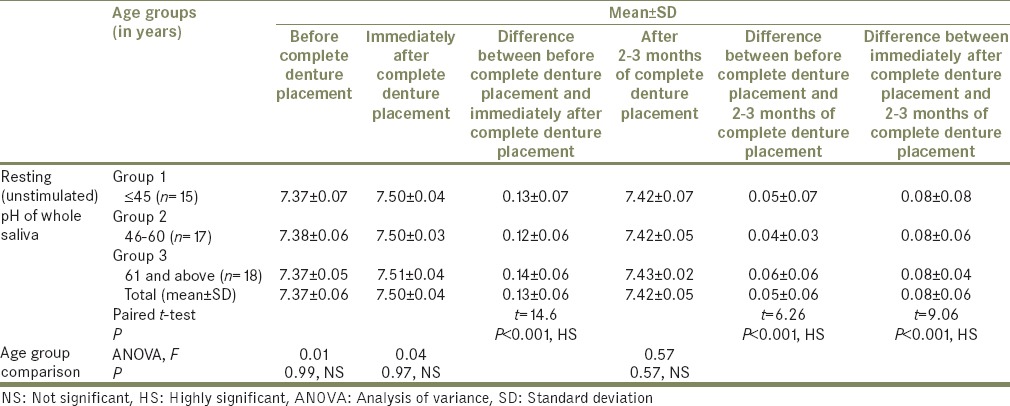

Table 4.

Mean, SD, total mean±SD, ANOVA, paired t-test values, and P values for resting (unstimulated) pH of whole saliva at different age groups that is, Groups 1, 2, and 3 (n=50) before, immediately after, and after 2-3 months of complete denture placement

Table 5.

Mean, SD, total mean±SD, ANOVA, paired t-test values, and P values for stimulated pH of whole saliva at different age groups that is, Groups 1, 2, and 3 (n=50) before, immediately after, and after 2-3 months of complete denture placement

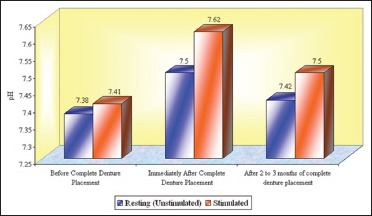

Graph 4.

The mean pH of whole saliva at the age group of ≤45 years that is, Group 1 (n = 15)

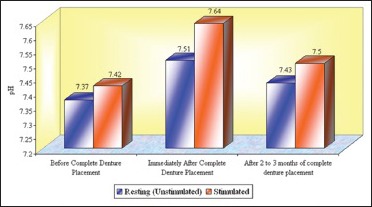

Graph 5.

The mean pH of whole saliva at the age groups between 46 and 60 years that is, Group 2 (n = 17)

Graph 6.

The mean pH of whole saliva at the age group of 61 years and above that is, Group 3 (n = 18)

Graph 7.

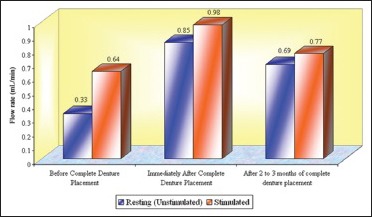

Total mean flow rates (mL/min) of whole saliva in different age groups that is, Groups 1, 2, and 3 (n = 50)

The results are summarized as follows:

Stimulated whole salivary flow rates were significantly higher than the resting (unstimulated) whole salivary flow rates obtained before, immediately after, and after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement (P < 0.001, HS);

There were significant differences in resting (unstimulated) whole salivary flow rates obtained before immediately after, and after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement (P < 0.001, HS);

There were significant differences in stimulated whole salivary flow rates obtained before immediately after, and after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement (P < 0.001, HS);

There were significant differences in pH between resting (unstimulated) and stimulated whole saliva (P < 0.001, HS);

There were also significant differences in pH determined before, immediately after, and after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement (P < 0.001, HS);

No statistically significant age-related variations in the resting (unstimulated) whole salivary flow rates were observed before, immediately after, and after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement (P = 0.11, 0.23; 0.83–NS)

No statistically significant age-related variations in the stimulated whole salivary flow rates were observed before, immediately after, and after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement (P = 0.77, 0.88; 0.49–NS).

DISCUSSION

During recent years, it has become apparent that saliva is critical for the maintenance and function of all tissues in the mouth. Therefore, any situation that disturbs saliva production or its composition will probably have broad negative sequelae in the mouth and may result in systemic complications.[5]

The presence of saliva is essential for the maintenance of healthy oral tissues. Severe reduction of salivary output not only results in a rapid deterioration in oral health but also has a detrimental impact on quality of life for the sufferer. Patients suffering from dry mouth experience difficulty with eating, swallowing, speech, retention of dentures, taste alteration, oral hygiene, trauma and ulceration of the oral mucosa, a burning sensation of the mucosa, candidal infections. Polypharmacy is very common among the older adult population, and many of the commonly prescribed drugs cause a reduction in salivary flow. Xerostomia also occurs in Sjögren's syndrome which is not an uncommon condition. Systemic diseases also have a profound effect on the salivary flow. Clearly, xerostomia is a problem which faces an increasingly large proportion of the population.[17]

Whole saliva is the mixture of secretions which enter the mouth in the absence of exogenous stimuli such as tastants or chewing. It is composed of secretions from the parotid, submandibular, sublingual, and minor mucous glands, but it also contains gingival crevicular fluid, desquamated epithelial cells, bacteria, leukocytes (mainly from the gingival crevice), and possibly food residues, blood, and viruses.[17]

The importance of whole saliva as a better predictor in identifying the persons with high Candida albicans count has been reported in the literature.[18]

Sialometry is the measure of the flow rate of saliva.[17,19]

Salivary flow is termed resting (unstimulated) when no exogenous or pharmacological stimulation is present and is termed (stimulated) when secretion is promoted by mechanical or gustatory stimuli or by pharmacological agents. When the secretion is stimulated mechanically, inert stimuli are used (chewing of paraffin wax or rubber bands) and thus do not add anything to the saliva.[8]

Since several factors can influence salivary secretion and composition, a precise standard for saliva collection must be established.[20]

The methods of collection of saliva include:

The subject bends his/her head forward and, after an initial swallow, allows saliva to drip off the lower lip into a graduated cylinder or preweighed container (draining method)

The patient is comfortably seated with eyes open, head tilted forward, and the patient is asked to spit at regular intervals into a graduated jar (spitting) method

Saliva is sucked continuously from the floor of the mouth with a suction tube and allowed to accumulate in a collection vessel (suction method); and,

Pre-weighed, absorbent swabs are inserted into the mouth and removed for weighing at the end of the collection period (swab method).[8]

The spitting method appeared to be the most reproducible.[8,21]

In the present study, spitting method for collection of whole saliva was used. Chewing paraffin wax (mechanical method) was used to stimulate whole saliva. Different stimuli have an important effect on the salivary composition, mainly because of their effect on the rate of flow. Mechanical stimuli that is, the presence of dentures themselves stimulate salivation but to a lesser degree than combined with the action of chewing inert material like paraffin wax.

In this study, an increase in mean whole salivary flow rate was found to be 0.33 mL/min to 0.85 mL/min in resting (unstimulated) and 0.64 mL/min to 0.98 mL/min in stimulated conditions, respectively, from before complete denture placement to that of immediately after complete denture placement. Hence, the mean difference of salivary flow rate was 0.52 mL/min and 0.34 mL/min in resting (unstimulated) and stimulated conditions, respectively.

The importance of stimulation and the stimulated salivary flow rate has been discussed by different authors.[17,22,23]

The increase in whole salivary flow rate which was found immediately after complete denture placement has a negative effect on the retention. However, some studies have showed a significant increase in maxillary denture retention with increased stimulated parotid gland secretions.[24] In the present study, the mean whole salivary flow rate when compared between 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement to immediately after complete denture placement, it was found to be decreased to 0.69 mL/min from 0.85 and 0.77 mL/min from 0.98 mL/min in resting (unstimulated) and stimulated conditions, respectively, thus indicating that there could be no loss of retention which was caused by the initial increase in the whole salivary flow which was found immediately after complete denture placement. Furthermore, the values for whole salivary flow rate after 2 to 3 months remained significantly high when compared with the baseline values obtained before the complete denture placement, suggesting the importance of stimulation, where the dentures themselves act as mechanical stimulants.

Salivary flow rates exhibit both diurnal and seasonal variations with the peaks in the midafternoon.[17] In our study, whole saliva was collected between clinical conditions 09:00 to 11:00 h. Therefore, it is important to standardize the time of day which saliva is collected.

The determination of a patient's salivary flow rate is a simple, noninvasive procedure. Both resting (unstimulated) and stimulated flow rates can be measured, and changes in flow can be monitored over time. Saliva defense properties reside principally in salivary flow rate, pH, and buffer capacity.[15] Both salivary flow rate and pH were determined in the present study.

Reduced salivary production is thought by some to be related to the aging process. Others, however, have not found any age-associated diminution in salivary output.[17,25,26,27,28,29,30]

Salivary flow rate is unrelated to age above 15 years. For a long time, it was believed that salivary flow decreased with age because such studies had been done on institutionalized, medicated patients. More recent research has shown that aging has little effect on either unstimulated or stimulated flow rate in normal healthy people who are not on medication.[17] However, in the present study, the selected participants were aged 30 years and above.

In this study, it was found that the mean resting (unstimulated) whole salivary flow rates in all the age groups (i.e., Groups 1, 2, and 3) showed no significant age-related variations before complete denture placement (ANOVA, F = 2.33, P = 0.11, NS), immediately after complete denture placement (ANOVA, F = 1.54, P = 0.23, NS), and after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement (ANOVA, F = 0.18, P = 0.83, NS).

The mean stimulated salivary flow rates in all the age groups (i.e., Groups 1, 2, and 3) showed no significant age-related variations before complete denture placement (ANOVA, F = 2.76, P = 0.07, NS), immediately after complete denture placement (ANOVA, F = 0.13, P = 0.88, NS), and after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement (ANOVA, F = 0.72, P = 0.49 NS). This lends to view that salivary flow rate appears to be independent of age in healthy nonmedicated subjects.[17,26,27,29]

Whether the flow rate is high or low is much less important than whether it has changed adversely in a particular individual. Dentists, however do not routinely measure the salivary flow rate, so that when a patient complains of having a dry mouth, it is impossible to judge whether or not a genuine reduction in flow has taken place. It would therefore be very advantageous if dentists included measurement of salivary flow as part of their regular examination which will serve as a yardstick for future measurements.[17]

Salivary secretion is affected by the number of systemic disorders and duration of the potentially xerogenic medications.[17,31] Arguably, the single most common side effect of many drugs is dry mouth. There is certainly evidence that as the number of medications being taken by an individual increase, there is a corresponding decrease in saliva. Decreased salivary flow rates and complaints of oral dryness are related to medication use in the elderly.[32]

The main factor affecting the composition of saliva is the flow rate. As the flow rate increases, the pH and concentration of some constituents rise, among them notably are bicarbonate, protein, sodium, and chloride. Bicarbonates rise dramatically in stimulated saliva, which is an effective buffer system.[33] While those of others fall like magnesium and phosphate.

The bicarbonate is the most important buffering system in saliva. Salivary pH is dependent on the bicarbonate concentration, an increase in which results in an increase in pH.

Importance of stimulation which resulted in the rapid increase in bicarbonate content which eventually increased the pH, contributed to the ability of saliva to counter the acid production locally in the oral cavity.[34]

In the present study, it was found that there was an increase in pH with increased salivary flow rate. The mean resting (unstimulated) pH before complete denture placement was 7.37, immediately after complete denture placement was 7.50, showing the mean increase in pH of 0.13 ± 0.06 (P < 0.001, HS). Determined after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement pH was 7.42. Mean difference from before denture placement was 0.05 ± 0.06 (P < 0.001, HS. The mean difference of 0.08 ± 0.06 decreases in pH from immediately after denture placement to 2 to 3 months of denture placement found was highly significant. However, it was not considered as low as it would have a negative effect on the buffering system.

The mean stimulated pH before complete denture placement was 7.42, immediately after complete denture placement was 7.63, showing the mean increase in pH of 0.22 ± 0.07 (P < 0.001, HS. Determined after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement, it was 7.50, showing mean increase of 0.08 ± 0.04 (P < 0.001, HS). The mean difference of 0.13 ± 0.05 decrease in pH from immediately after placement found was highly significant. However, it was not considered as low as it would have a negative effect on the buffering system. Still the persistent increase in the stimulated pH, in particular, could be beneficial to oral and dental health.[35] The results obtained are consistent with the previous reports.[34]

Individuals with xerostomia will thus have a low salivary pH and a low buffering capacity because of the low bicarbonate content, ultimately leading to sequelae of problems.[17] Low levels of pH indicate a lack of salivary flow and buffering capacity, which leads to hyperacidity of the environment.[35]

In the present study, all the study groups that is, Groups 1, 2, and 3 showed no age-related variations in the mean unstimulated pH of whole saliva before complete denture placement (ANOVA, F = 0.01, P = 0.99, NS), immediately after complete denture placement (ANOVA, F = 0.04, P = 0.97, NS) and after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement (ANOVA, F = 0.57, P = 0.57, NS), respectively. Furthermore, there were no age-related variations found in stimulated pH of whole saliva in all the study groups that is, Groups 1, 2, and 3, before complete denture placement (ANOVA, F = 0.11, P = 0.89, NS), immediately after complete denture placement (ANOVA, F = 1.71, P = 0.19, NS), and after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement (ANOVA, F = 0.003, 0.003, P = 0.99, NS), respectively.

A more detailed study of salivary gland physiology, across the different age spectrum in edentulous individuals and correlation of different salivary factors is required to confirm the age-related changes.

CONCLUSION

The following conclusions were made from this study:

Stimulated whole salivary flow rates were significantly higher than the resting (unstimulated) whole salivary flow rates obtained before, immediately after, and after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement

It was found that there were significant differences in resting (unstimulated) whole salivary flow rates obtained before, immediately after, and after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement

There were also significant differences in stimulated whole salivary flow rates obtained before, immediately after, and after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement

Initial placement of the complete denture significantly increased the whole salivary flow rate, stimulation further enhanced the flow rate

There were significant differences in the pH between resting (unstimulated) and stimulated whole saliva

There were also significant differences in the pH determined before, immediately after, and after 2 to 3 months of complete denture placement

No significant age-related variations in the whole salivary flow rate and pH were observed in healthy nonmedicated individuals.

Therefore, the salivary factors such as salivary flow rate and pH are to be better analyzed for their potential to add benefits to the oral health in particular and overall health in general of an individual.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Enberg N, Alho H, Loimaranta V, Lenander-Lumikari M. Saliva flow rate, amylase activity, and protein and electrolyte concentrations in saliva after acute alcohol consumption. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92:292–8. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.116814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamkin MS, Oppenheim FG. Structural features of salivary function. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1993;4:251–9. doi: 10.1177/10454411930040030101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shern RJ, Fox PC, Cain JL, Li SH. A method for measuring the flow of saliva from the minor salivary glands. J Dent Res. 1990;69:1146–9. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690050501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parvinen T, Larmas M. The relation of stimulated salivary flow rate and pH to Lactobacillus and yeast concentrations in saliva. J Dent Res. 1981;60:1929–35. doi: 10.1177/00220345810600120201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Månsson-Rahemtulla B, Techanitiswad T, Rahemtulla F, McMillan TO, Bradley EL, Wahlin YB. Analyses of salivary components in leukemia patients receiving chemotherapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:35–46. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90151-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pedersen AM, Bardow A, Jensen SB, Nauntofte B. Saliva and gastrointestinal functions of taste, mastication, swallowing and digestion. Oral Dis. 2002;8:117–29. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.02851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samarawickrama DY. Saliva substitutes: How effective and safe are they? Oral Dis. 2002;8:177–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.02848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yurdukoru B, Terzioglu H, Yilmaz T. Assessment of whole saliva flow rate in denture wearing patients. J Oral Rehabil. 2001;28:109–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2001.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Streckfus CF, Bigler LR. Salivary glands and saliva. Oral Dis. 2002;8:69–76. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.1o834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandel ID. The diagnostic uses of saliva. J Oral Pathol Med. 1990;19:119–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1990.tb00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitasako Y, Moritsuka M, Foxton RM, Ikeda M, Tagami J, Nomura S. Simplified and quantitative saliva buffer capacity test using a hand-held pH meter. Am J Dent. 2005;18:147–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodds MW, Johnson DA, Yeh CK. Health benefits of saliva: A review. J Dent. 2005;33:223–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehringer EJ. The saliva as it is related to the wearing of dentures. J Prosthet Dent. 1954;4:312–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandel ID. Relation of saliva and plaque to caries. J Dent Res. 1974;53:246–66. doi: 10.1177/00220345740530021201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baum BJ. Evaluation of stimulated parotid saliva flow rate in different age groups. J Dent Res. 1981;60:1292–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345810600070101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gandara BK, Izutsu KT, Truelove EL, Ensign WY, Sommers EE. Age-related salivary flow rate changes in controls and patients with oral lichen planus. J Dent Res. 1985;64:1149–51. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660110201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ben-Aryeh H, Shalev A, Szargel R, Laor A, Laufer D, Gutman D. The salivary flow rate and composition of whole and parotid resting and stimulated saliva in young and old healthy subjects. Biochem Med Metab Biol. 1986;36:260–5. doi: 10.1016/0885-4505(86)90134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edgerton M, Tabak LA, Levine MJ. Saliva: A significant factor in removable prosthodontic treatment. J Prosthet Dent. 1987;57:57–66. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(87)90117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mandel ID. The functions of saliva. J Dent Res. 1987;66:623–7. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660S203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dawes C. Physiological factors affecting salivary flow rate, oral sugar clearance, and the sensation of dry mouth in man. J Dent Res. 1987;66:648–53. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660S107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tylenda CA, Ship JA, Fox PC, Baum BJ. Evaluation of submandibular salivary flow rate in different age groups. J Dent Res. 1988;67:1225–8. doi: 10.1177/00220345880670091501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niedermeier WH, Krämer R. Salivary secretion and denture retention. J Prosthet Dent. 1992;67:211–6. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(92)90455-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osterberg T, Birkhed D, Johansson C, Svanborg A. Longitudinal study of stimulated whole saliva in an elderly population. Scand J Dent Res. 1992;100:340–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1992.tb01084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edgar WM. Saliva: Its secretion, composition and functions. Br Dent J. 1992;172:305–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4807861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Percival RS, Challacombe SJ, Marsh PD. Flow rates of resting whole and stimulated parotid saliva in relation to age and gender. J Dent Res. 1994;73:1416–20. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730080401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navazesh M, Wood GJ, Brightman VJ. Relationship between salivary flow rates and Candida albicans counts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;80:284–8. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80384-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferguson DB. The flow rate of unstimulated human labial gland saliva. J Dent Res. 1996;75:980–5. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750041301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Navazesh M, Brightman VJ, Pogoda JM. Relationship of medical status, medications, and salivary flow rates in adults of different ages. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:172–6. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(96)80410-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edgar WM, O’Mullane DM. Saliva and Oral Health. 2nd ed. London: British Dental Association; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen JL, Karatsaidis A, Brodin P. Salivary secretion: Stimulatory effects of chewing-gum versus paraffin tablets. Eur J Oral Sci. 1998;106:892–6. doi: 10.1046/j.0909-8836..t01-7-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sreebny LM. Saliva in health and disease: An appraisal and update. Int Dent J. 2000;50:140–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2000.tb00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Humphrey SP, Williamson RT. A review of saliva: Normal composition, flow, and function. J Prosthet Dent. 2001;85:162–9. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2001.113778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaufman E, Lamster IB. The diagnostic applications of saliva – A review. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13:197–212. doi: 10.1177/154411130201300209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diaz-Arnold AM, Marek CA. The impact of saliva on patient care: A literature review. J Prosthet Dent. 2002;88:337–43. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2002.128176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polland KE, Higgins F, Orchardson R. Salivary flow rate and pH during prolonged gum chewing in humans. J Oral Rehabil. 2003;30:861–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2003.01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atkinson JC, Grisius M, Massey W. Salivary hypofunction and xerostomia: Diagnosis and treatment. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49:309–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]