“… it is better to dissect nature, than to reduce her to abstraction”

Francis Bacon, Novum oragnum scientiarum, 1620

Introduction

December 31st, 2014 marked the 500-year anniversary of the birth of Andreas Vesalius. Vesalius, considered as the founder of modern anatomy, had profoundly changed not only human anatomy, but also the intellectual structure of medicine. The impact of his scientific revolution can be recognized even today. In this article we review the life, anatomical work, and achievements of Andreas Vesalius.

The life of Andreas Vesalius

Andreas van Wesel (Figure 1) was born on December 31st, 1514, in Brussels, which was a city of the Duchy of Brabant (the southern portion of Belgium) and the Holy Roman Empire. His surname meant ‘weasel’ and his family's coat of arms, as depicted in Vesalius’ masterpiece (Vesalius 1543a), represented three weasels (Figure 2). He came from a family of renowned physicians and pharmacists; both his father (pharmacist) and grandfather (physician) served the Holy Roman Emperor (for a comprehensive biography of Vesalius, see Cushing 1962). In 1529, he left Brussels to study at the Catholic University of Leuven (Figure 3), where he embarked on the arts courses. As wealthy young man of his time, Vesalius studied rhetoric, philosophy and logic in Latin, Classical Greek, and Hebrew at the Collegium Trilingue. While still in Leuven, Vesalius’ interest focused on medicine. To pursue his medical education, he moved to France from 1533 to 1536 where he studied at the University of Paris.

Figure 1.

Andreas Vesalius portrait in the “Hall of Medicine” at the Bo Palace of the University of Padua.

Figure 2.

Coat of arms of the Vesalius family, showing three weasels, as appears at the top of the frontispiece of his masterpiece: De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (Vesalius 1543a).

Figure 3.

Seal of the Catholic University of Leuven.

Paris had long been the leading medical school north of the Alps. Teaching took the form of lectures on particular texts in Latin, especially Hippocrates, Galen, Avicenna, and Rhazes. At that time, Paris was embracing the Humanistic intellectual movement, which was established almost two centuries previously by Petrarch (1304–1374) in northern Italy and in Padua in particular. As part of Humanism, many classical books and manuscripts were being retranslated ad fontes, i.e., from the original source. Trained in classical languages, Vesalius was strongly influenced by the humanist faculty members in Paris and their retranslations of Galen. However, practical instruction was rare in Paris. Anatomical dissection was a relatively recent and infrequent exercise. Anatomy was primarily learned from a book, especially the Introduction to Anatomy of Mondino de’ Liuzzi (1270–1326), a Bolognese professor who had lived and taught two centuries earlier, and whose anatomy was based on Galen's work (first edition: Mondino 1475/1476).

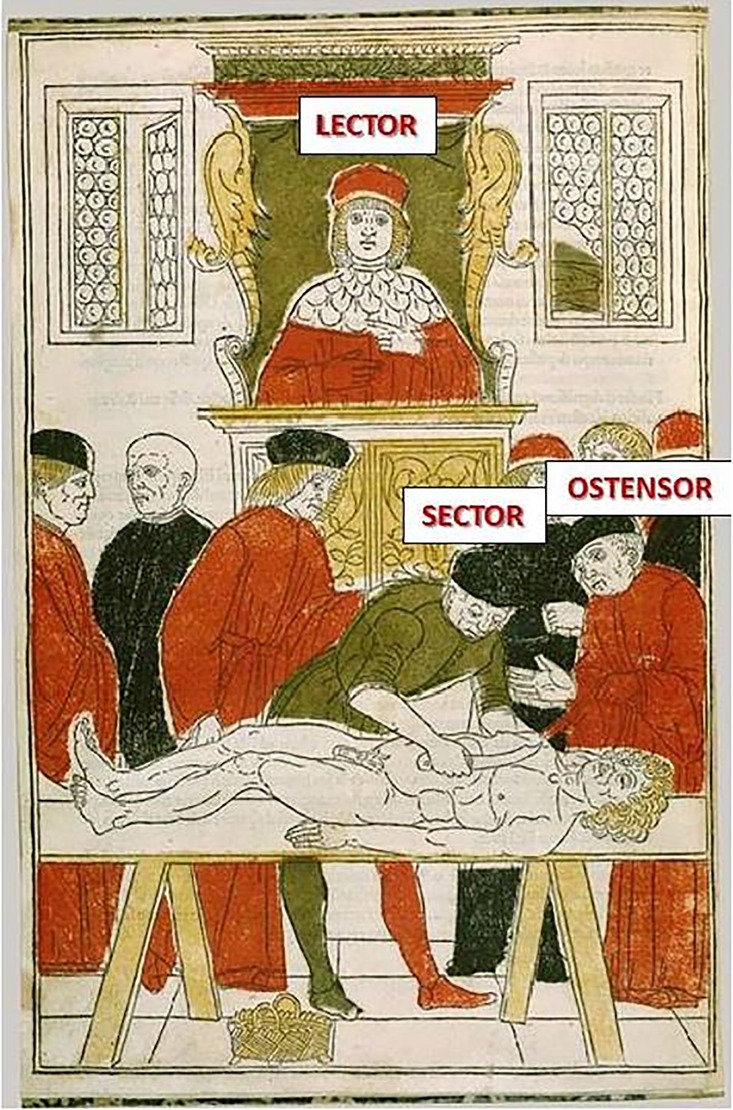

When an anatomy took place, a surgeon or an assistant cut up the body (sector). The professor (lector) read the words of Mondino, attempting to set his instruction into a broad context of medical and philosophical knowledge. He was supported by an assistant (ostensor), who indicated on the cadaver the parts explained from the text (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Lesson of anatomy from the “Fasciculo de medicina” (Ketham 1494) following the medieval method. The professor on the chair is thought to be Mondino de’ Liuzzi. The professor was called lector, the barber dissecting the body was called sector, while the assistant of the professor, in this scene aside the sector, was called ostensor.

The outbreak of war between France and the Emperor put an end to Vesalius’ stay in Paris. In 1536, Vesalius returned to Brabant to spend another year at the Catholic University of Leuven. During that period, he prepared a paraphrase on the work of the 10th-century Arab physician, Rhazes (O'Malley 1964).

In 1537, Vesalius, travelled to north of Italy, where there were the best medical schools, among them Padua, which he referred to as “the most famous gymnasium in the world” (Vesalius 1543a). He graduated in medicine the same year at Padua, and the day after his graduation, he became professor of Anatomy and Surgery until 1543 (Cushing 1962; O'Malley 1964).

It was in Padua where Vesalius made his most important contributions as an anatomist, humanist, and lecturer. The University of Padua enjoyed a long tradition of academic freedom, and anatomical dissections had been part of the medical education for some time (Premuda & Ongaro 1965–1966). Vesalius here introduced artistic drawings and detailed printed sheets to support his anatomical teaching. In 1538, he published the Tabulae anatomicae sex, (Six anatomical plates), which were six sheets drawn by the artist Jan van Calcar (c.1499–1546) (Figure 5), based largely on Vesalius’ own drawings (Vesalius 1538). Jan van Calcar was a Brabant born Italian painter, and one of Titian's (c.1480–1576) apprentices. At least one of these plates, the Tabula II about liver and vena cava, was based on an autopsy done by Vesalius on 6th December 1537 in Padua, on a body of an 18-year-old male. In the National Library of Vienna, in fact, there is a manuscript of Vitus Tritonius Athesinus, friend of Vesalius and student of medicine in Padua, about this autopsy, in which there is a sketch of the liver almost identical to the illustration in the second table of Vesalius’ Tabulae (Figure 6) (O'Malley 1958).

Figure 5.

Portrait of Jan van Calcar.

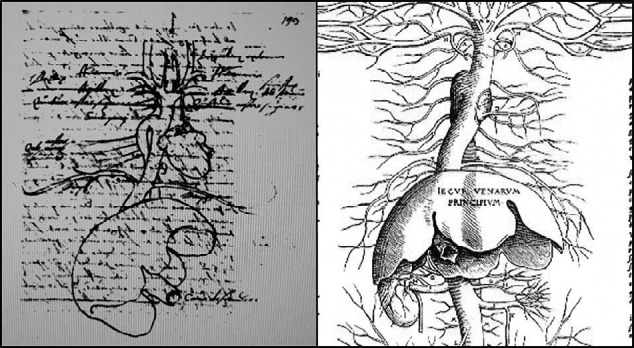

Figure 6.

On the left: drawing of the liver and vena cava made by Vitus Tritonius Athesinus, friend of Vesalius and student of Medicine in Padua, from a manuscript preserved at the National Library of Vienna (O'Malley 1958); on the right: close-up of the Tabula II of Vesalius’ Tabulae anatomicae sex (Vesalius 1538), from which it is possible to appreciate the strict similitude with Vitus’ drawing.

Taking advantage of the intellectual climate of Padua, Vesalius completed his masterpiece, the De humani coporis fabrica libri septem in the summer of 1542 (Figure 7). It was based on his knowledge of Galenic anatomy and physiology, and on the evidence he had gleaned from his many dissections – principally made in Padua – by which he was able to demonstrate that Galen never dissected a human corpse. Once the writing was finished, and the blocks for the illustrations were almost ready to be sent from Venice to his printer, Johannes Oporinus (1507–1568) (Figure 8), in Basle, Vesalius departed to Basle to supervise the printing of his masterpiece. The Venetian Senate and the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V (1500–1558) obtained the copyright, protecting the Fabrica from unauthorized copying (Vesalius 1543a) and the book is considered a masterpiece of Renaissance printing.

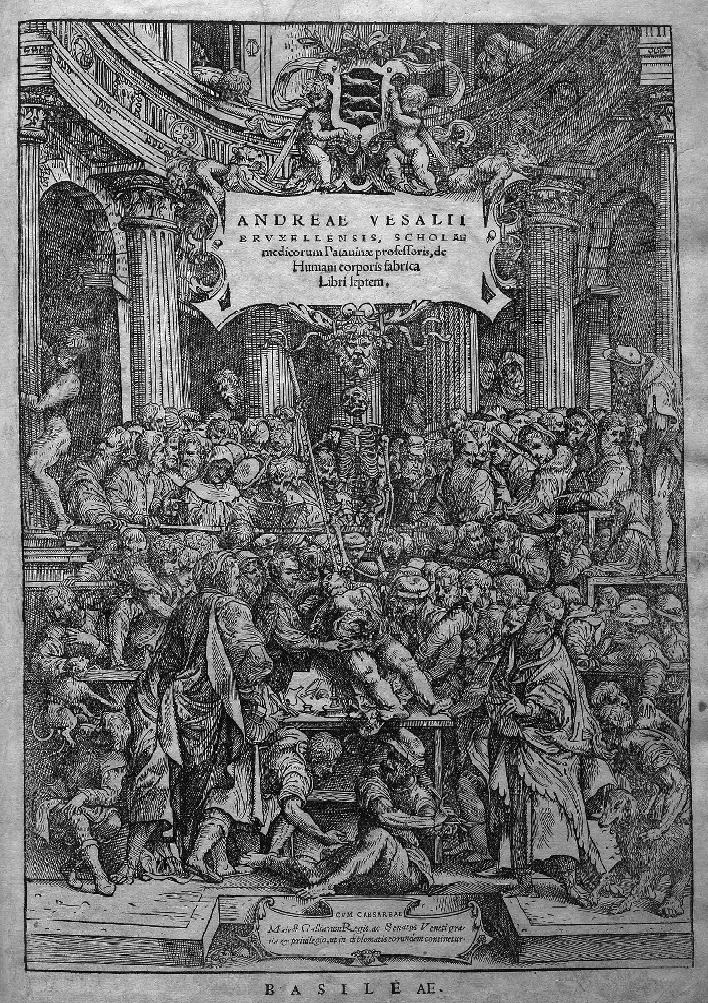

Figure 7.

Frontispiece of the first edition of Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (1543), where Vesalius is making a dissection in a crowded anatomical amphitheater.

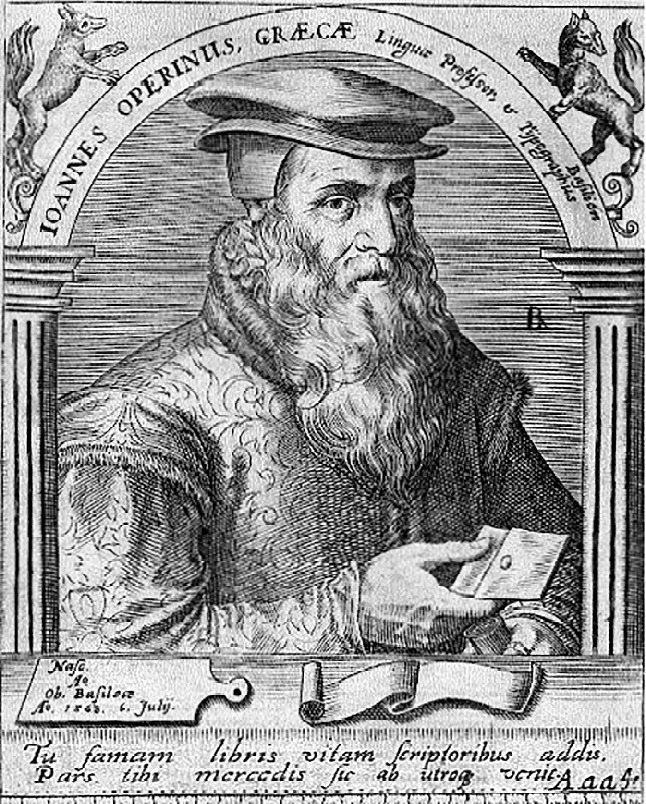

Figure 8.

Engraving depicting Johannes Oporinus, editor of Vesalius’ most important works.

Vesalius arrived in Basle in January 1543, where he continued to dissect. The skeleton he constructed from the bones of an executed criminal, Jacob Karrar, is still preserved in the Anatomy Museum of Basle's University (Olry 1998) (Figure 9). This specimen is estimated to be the oldest anatomical preparation of a skeleton in the world. During his time in Basle, Vesalius also prepared a digest of the Fabrica, the Epitome, for students, a mere six chapters long with nine illustrations, printed on poorer quality paper but of even larger size to make their details clearer (Vesalius 1543b).

Figure 9.

The skeleton prepared by Vesalius still now preserved at the Anatomy Museum of the Institute of Anatomy of the University of Basel.

Later, Vesalius presented the Fabrica to Charles V and was enrolled at once as one of the Emperor's household physicians. In 1544, he married Anne van Hamme, the daughter of a rich counsellor of Brussels, who bore him a daughter, also named Anne, in 1545. He continued to dissect, but he was increasingly called in to act as a physician and surgeon, proving how his anatomical knowledge could be useful also to practice medicine (Suy & Forneau 2015).

By 1555, Vesalius finished a revised edition of the Fabrica (Vesalius 1555) (Figure 10). The revised edition of the Fabrica can be considered as a novel major contribution, rather than a mere update of the earlier version. The revised Fabrica was based even more on Vesalius’ own observations and departed more markedly from traditional Galenism. It gave a strong and uncompromising message that the human body could only be understood by a clear and careful anatomical investigation into human corpses. Notable examples to this message are his description of the anatomy of the uterus and the fetus, and his criticism of Galenic views regarding the permeability of the interventricular septum (see later) (Zampieri et al. 2014).

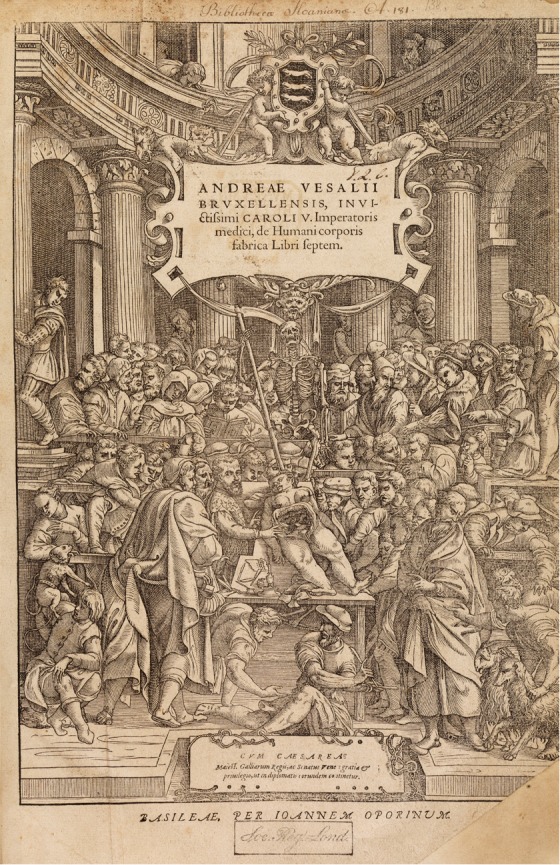

Figure 10.

Frontispiece of the second edition of Vesalius’ Fabrica (1555).

Recently, it has been discovered that Vesalius was preparing a third edition of the Fabrica, the great majority of corrections being stylistic, altering the Latin words but not the overall meaning. This work, however, never saw the light of day (Nutton 2012).

In 1556, Charles V abdicated his throne and retired in Spain. Vesalius remained in Brussels, and the new King Phillip II (1527–1598) recruited him again. In the spring of 1559, the French King, Henri II (1519–1559), received a wooden lance in his right orbit and temple during a tournament in Paris. Vesalius was immediately called for, joining Ambroise Paré (1510–1590) and other leading surgeons from France in an attempt to save the king (Figure 11) (Eftekhari et al. 2015).

Figure 11.

Engraving from the collection Quarante Tableaux, published in France between 1569 and 1570 by the engravers Jean Perrissin and Jacques Tortorel, showing where Henri II was cured and died, where also Andreas Vesalius and Antoine Parè were present. Vesalius and Parè are probably the two physicians discussing together at the center of the room, in front of the table.

Eleven days later, the King finally died after suffering meningismus, fever, left-sided paralysis, and difficulty in respiration. Vesalius conducted the autopsy and wrote a detailed medical report, which included both clinical history and autopsy findings on the way in which the lance had penetrated the skull, but without causing a fracture. This again shows the important relationship between anatomy and clinics, an aspect that has been probably underestimated by historians of medicine, because they focused too heavily on his anatomical research.

Following a brief return home, Vesalius moved with Philip II to Spain, where he composed his last anatomical essay, a critique of the Anatomical observations of Gabriele Falloppia (1523–1562) (Figure 12). In 1564, Vesalius left Spain with his family. His wife and daughter returned to Brussels, while Vesalius made his way for a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. The reasons of this trip have never been completely clarified. He first stopped at Venice, where it was said that the Venetian senate appointed him once more to the Chair of Anatomy at Padua, in succession to Falloppia, who had died in 1562. However, the return journey from the Holy Land was a catastrophe. The boat on which he set sail was allegedly driven before a storm for forty days without landfall, provisions ran short, and Vesalius fell ill. The ship finally made land on the island of Zante (now Zakynthos) off the west coast of Greece, and Vesalius came ashore, only to die almost immediately (O'Malley 1964).

Figure 12.

Gabriele Falloppia's portrait in the “Hall of Medicine” at the Bo Palace of the University of Padua.

Vesalius’ scientific achievements

The most important scientific achievements of Vesalius were favored by the intellectual environment of the University of Padua, which was, in fact, one of the most advanced cultural centers of Europe since the 14th century. The Republic of Venice, of which Padua was a part from 1405, guaranteed tolerance and freedom of researching and teaching at the University, attracted the best professors from foreign countries, and allowed the circulation of classic rare books and manuscripts (Zampieri et al. 2013). Venice became one of the principal European centers of printing, and Padua had access to new editions of classic science and medicine texts, such as the opera omnia of Aristotle's and Galen's works. Moreover, in Padua, between the 14th and 16th centuries, Aristotelian methodology became the core of research for different disciplines, from physics to medicine. In sharp contrast to the medieval thoughts, the Aristotelian methodology was focused on the study of physics and biological nature with their own principles and laws and without recurring to external, metaphysical forces (Telesio 1586). Compared to other European centers, Padua had older anatomical traditions and anatomy was considered a “noble” science. Anatomy was practiced, for medico-legal cases, from the beginning of 14th century (Premuda & Ongaro 1965–1966).

Vesalius’ stay in Padua was fundamental to his scientific achievements, and his first publication, the Tabulae anatomicae sex (Vesalius 1538), where Vesalius highlighted some fundamental anatomical errors in Galen's physiology. By the time of the publication of the Fabrica (Vesalius 1543a), at the end of his professorship in Padua, Vesalius understood that Galen's anatomy was largely wrong. The Tabulae were six anatomical tables published by Vesalius in the year following his appointment as professor of Surgery and Anatomy at the University of Padua in 1537 (Singer & Rabin 1946). They were edited and illustrated by Jan van Calcar (Figure 13), who is supposed to be also the author of the illustrations of the Fabrica. The book was innovative because it was based on illustrations, rather than verbal descriptions of human anatomy, as almost all previous anatomical treatises had been, but these illustrations were still strictly related by Galen's orthodoxy. Vesalius, for instance, in the Tabula III about the arteria magna (aorta) and heart, depicted the “rete mirabile”, a network of vessels at the base of brain that Galen supposed existed in humans, while in fact it exists only in other mammals such as cow and ox.

Figure 13.

Close-up of the sixth table of the Tabulae anatomicae sex, where von Calcar is attributed as editor of the publication.

In the same table, Vesalius indicated the heart such as the “source of vital spirit and the principle of arteries” (cor vitalis facultatis fomes et arte princ) (Figure 14). According to Galenian anatomy and physiology, the liver was the source of venous system, while the heart was the source of the arterial one. The left ventricle of the heart was the source of the “vital spirit” by the mixture of blood (“natural spirit”), coming from the right to left ventricle through invisible pores, and air, coming from pulmonary vein. Vital spirit was the carrier of the “natural heat” through the arteries, without which the body would have been cold.

Figure 14.

Close-up of the III table on Arteria magna (the aorta) of Vesalius’ Tabulae anatomicae sex (Vesalius 1538). The heart is defined as “source of vital spirit and the arterial system”; the pulmonary vein is the structure which “brings air from lungs to the left ventricle” (letter “Q” of the caption on the left). All of these ideas were strictly Galenic.

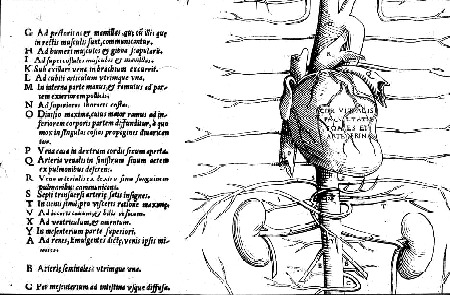

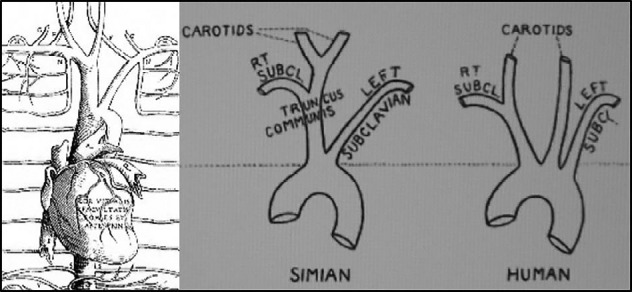

Vesalius also followed the part of Galen physiology describing the “pulmonary vein bringing air from lungs to left atrium” (arteria venalis in sinistrum sinum aerem ex pulmonibus deferens) (Vesalius 1538; Zampieri et al. 2014) (Figure 14). Finally, another of Galen's anatomical errors regards the structure of human carotids (Singer & Rabin 1946; Pagel 1964). Vesalius represented left and right carotids emerging from the “truncus communis”, while in humans the left carotid emerges separately from aortic arch. The “truncus communis” structure exists in simians, which proves once again that Galen did not dissect humans, only primates and other mammals (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

On the left: close-up from the Tabula III of Vesalius’ Tabulae anatomicae sex (Vesalius 1538), showing the heart and the structure of the carotids; on the right: structure of the carotids in human and simian, demonstrating that Vesalius represented in man the structure typical of simian, following Galen's anatomy (picture taken from: Singer & Rabin 1946).

The publication of his masterpiece, both in its first and second editions (Vesalius 1543a; 1555), is considered a turning point not only for human anatomy, but also for medicine in general, because this wonderful work contained not only seminal discoveries in this discipline, but also a new method in medical science compared to medieval theory and practice.

The Preface to the first edition, dedicated to Charles V, is the most significant text from a methodological point of view (Premuda 1964). Vesalius complained of the disaggregation of medical art in what we would now call different specialties, and more particularly the fact that physicians have opposed “the use of the work of hands” and relegated it to inexperienced and ignorant surgeons and barbers (Vesalius 1543a).

On the contrary, Vesalius strongly supported that surgery was an ancient and useful part of medicine itself, not a separate discipline, which was explicitly based on the “investigation of nature”. All the Preface of the Fabrica can be seen as a defense of the “hand” in its contribution to the knowledge of the body and medicine (Premuda 1964): “[…] when the hand is used, medicine flourishes; when it is neglected, medicine languishes; when it is restored to use, medicine can flourish again” (Vesalius 1543a). This is even more significant because medieval medicine was speculative and adverse toward practical knowledge (Murdoch 1982).

In contrast to conventional anatomical teaching, Vesalius was a lecturer, a demonstrator and a dissector all at the same time. The Middle Age model of teaching anatomy required the presence of three “actors”: Lector, the professor of anatomy who read the textbooks of Mondino de’ Liuzzi without touching the cadaver; Ostensor, the assistant who indicated the parts of the cadavers described by the professor at any time; and Sector, who was the vulgar “barber” performing the dissection with his hands (Figure 4).

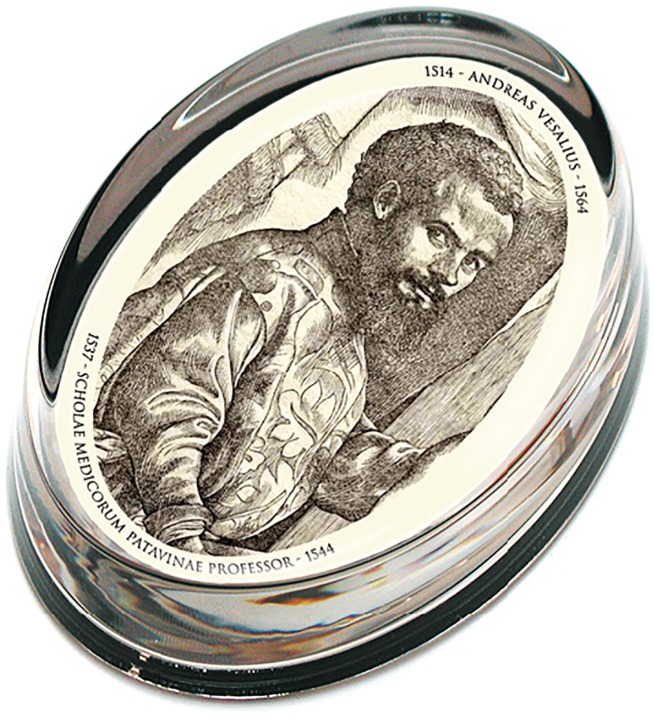

Vesalius harshly criticized this model, describing as: “[…] the hateful method by which one dissects the body and another describes its parts: the first, perched on a pulpit like a crow, haughtily repeating ideas that he didn't learn directly from the cadaver, but that he read in other's books” (Vesalius 1543a). In the hardcover of the Fabrica and in Vesalius’ portraits inside the book, his innovation is immediately appreciable. Vesalius is depicted doing an autopsy on the cadaver of a woman, touching the body with his right hand and pointing his left hand's finger (Figure 16). In this way, Vesalius visually demonstrated to personify all the three actors of the previous method. He was the Professor of Anatomy (Lector), in fact, he signed the book as Andreas Vesalius “Scholae Medicorum Patavinae Professor” (Figure 17), he personified the Ostensor with his left hand and the Sector with his right hand.

Figure 16.

Close-up of the frontispiece of De humani corporis fabrica (Vesalus 1543a), depicting Vesalius personifying all the three figures of the previous method for teaching anatomy: he was lector, because professor of anatomy, ostensor, because he indicated, with his left hand, what he was explaining during the dissection, and sector, because he made the dissection himself with his right hand.

Figure 17.

Paperweight celebrating the 500 years from the birth of Andreas Vesalius (1514–2014), produced by the University of Padua, where Vesalius is Scholae medicorum patavinae professor, as Vesalius defined himself in the Fabrica (Vesalius 1543a).

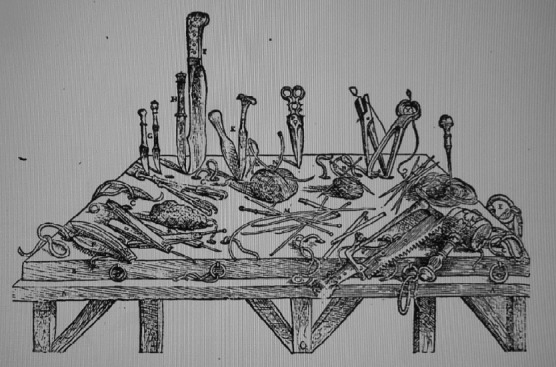

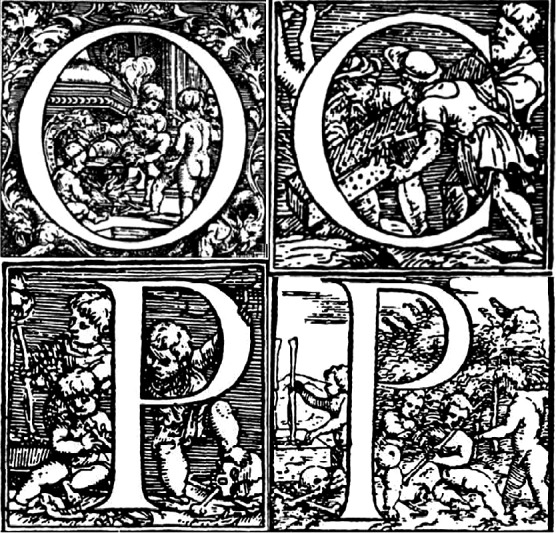

To confirm the importance of the role of sector personified by Vesalius, the Fabrica deserves a particular attention to the description of both the anatomical instruments (Figure 18), and the dissection techniques. Vesalius describes the techniques to prepare bones specimens. Osteology is probably the most advanced part of his anatomical research and, as proved by the Basle specimen, he was particularly skilled in skeleton preparation. He described different methods in his Fabrica, represented also in some wonderfully illustrated initials (Vesalius 1543a). He used, first of all, the classic method of boiling bodies to extract bones. Another method consisted of intially removing the majority of soft tissue. Then Vesalius covered the specimen with lime and placed it in a perforated wooden casket for a time. Then the casket was firmly tied down at the bottom of a river, where the current gradually removed the remaining soft tissue as it flowed through the casket (Olry 1998) (Figure 19).

Figure 18.

Illustration in Vesalius’ Fabrica of a table for animal vivisection with anatomical instruments both for human anatomy and animal vivisection (Vesalius 1543a).

Figure 19.

Capital letters of the Fabrica showing methods of preparing bones specimens. On top left: capital letter “O” of the 1543 edition, showing the method of boiling bodies to extract bones. On top right, capital letter “C” of the 1543 edition, showing three men who carry a casket full of holes about to be immersed in a river. After having removed the majority of soft tissue, Vesalius covered the specimen with lime and placed it in a perforated wooden casket for a time. Then the casket was firmly tied down at the bottom of a river, where the current gradually removed the remaining soft tissue as it flowed through the casket (Olry 1998). On bottom left: capital letter “P” of 1543 edition, showing cherubs reconstructing the skeleton from the bones obtained with the methods previously described. On bottom right: capital letter “P” of 1555 edition, showing the same scene.

As a Humanist, Vesalius recommended his students read the anatomy texts of Galen rather than Mondino. Vesalius expressed his conviction that mere book learning was not enough and that demonstrable evidence should take precedence over the written text. This is another fundamental methodological innovation of Vesalius. Thanks to his direct observation, based on his own dissections of cadavers, and his reading of Galen's books, Vesalius was able to scientifically demonstrate that Galen's anatomy was largely wrong, because Galen had never dissected human bodies.

We have to bear in mind that, at that time, Galen was considered the most up-to-date knowledge in medicine, not only because Galen was the most important authority from the Middle Age, but also because in Vesalius’ time the original works of Galen were being rediscovered. This is thanks in part to the publication, in Latin, of his original works, free from the interpretations of Arabic translations.

Medical humanists of the 15th and 16th centuries rediscovered a very modern Galen, a physician who stressed the importance of experience, practice and anatomy for medicine, and the need for a physician to travel abroad and acquire a universal knowledge. As a consequence, it was even more significant that Vesalius was able to see beyond Galen's new orthodoxy. Vesalius, in fact, was well aware “[…] how physicians (as well as followers of Aristotle) are upset when they ascertain that Galen, in the course of just one anatomical demonstration, gets wrong more than 200 times in the right description of the parts, the harmony, the use and the function of human body” (Vesalius 1543a).

Vesalius also showed why Galen was wrong: “Indeed, those who are now dedicated to the ancient study of medicine […] are beginning to learn to their satisfaction how little and how feebly men have laboured in the field of Anatomy to this day from the times of Galen, who […] did not dissect the human body; and the fact is now evident that he described (not to say imposed upon us) the fabric of the ape's body, although the latter differs from the former in many respects” (Vesalius 1543a).

That Galen made many mistakes was a foregone conclusion, since human and ape anatomies are very different. Between Galen's errors, Vesalius showed that the sternum consisted of three sections, instead of seven, that the mandible consisted of one bone, instead of two, that the “rete mirabile” did not exist in man, and that nerves were not hollow. These and many others findings became the starting point for a new anatomy based on the “book of nature” rather than on classic authorities.

To give a more solid foundation to his discoveries, Vesalius widely used the new instrument of anatomical illustration. Before Vesalius, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) produced wonderful and precise anatomical illustrations, but his works have never been published and surely didn't influence Vesalius (Thiene & Zampieri, 2013). Berengario da Carpi (1466–1530), professor of anatomy in Bologna, published the first anatomical illustrations. He edited two enlarged editions of Mondino's anatomical work, but his Isagogae breves had a major impact, with many editions in just a few years (Berengario 1523). However, Berengario's illustrations can be considered as simply a first attempt and do not compare to Vesalius’ achievement.

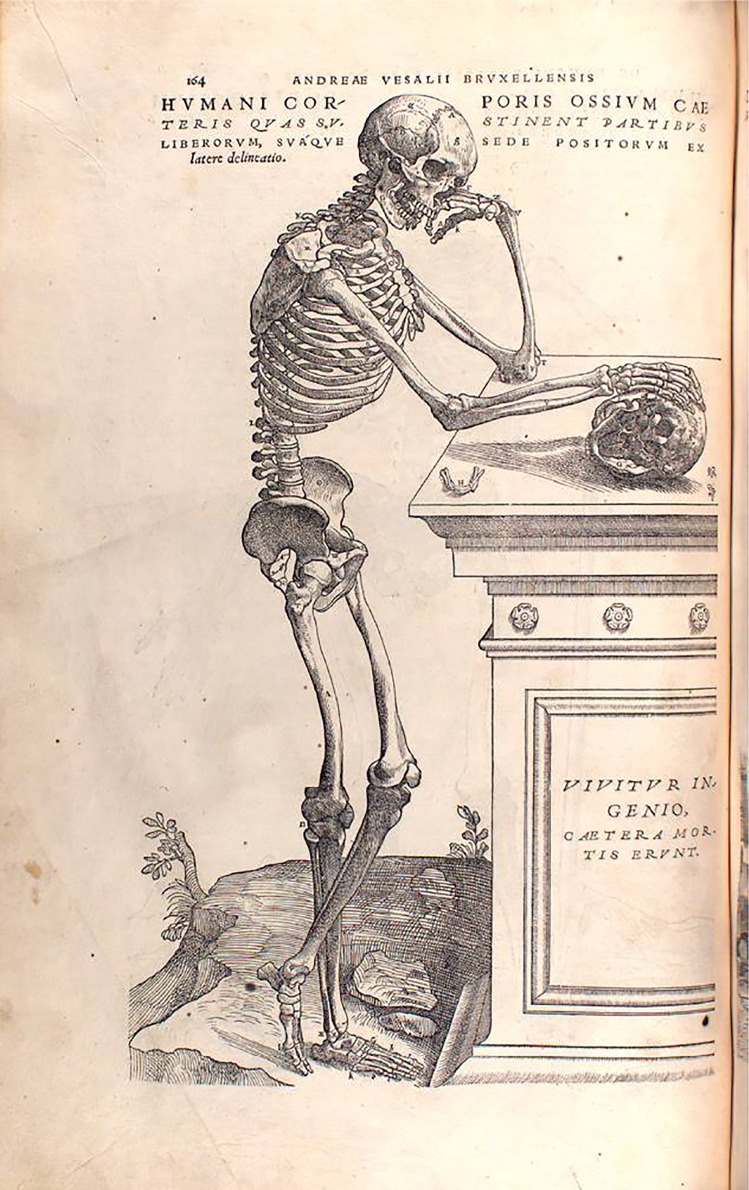

Vesalius considered anatomical illustrations such as a scientific foundation for anatomy in the same way they were for geometry (Vesalius 1543a). In Vesalius’ Fabrica there are more than 250 illustrations, some of the whole body, some of specific organs and parts of organs, some of anatomical instruments and techniques (Saunders & O'Malley 1950). Many of them shows cadavers in allegorical poses and imaginary, but realistic landscapes (Figure 20). Given that body was a noble object of study, in contrast to Middle Age attitude in which body and nature were humble objects of study, it deserved to be represented by the most beautiful and realistic images. As already mentioned, these pieces of art have been attributed to Jan van Calcar, painter who worked at the Titian school in Venice (Hazard 1996). Probably Vesalius choose van Calcar because he came from a painting school focused on the vivid representation of nature and human emotions, an approach perfectly combined with his own (Premuda 1963–1964).

Figure 20.

One of the Vesalius’ plates on the human skeleton, with the figure in an allegoric pose, thinking with a skull in his right hand, and a Latin inscription in the base where the skull is posed: “Vivitur ingenio, caetera mortis erunt”. Which means: genius lives on, all else is mortal.

Vesalius’ new anatomy would have brought not only a new morphological knowledge, but also a new physiology, which fully developed in the 16th and 17th centuries. Vesalius himself stressed the importance of understanding the function, that is the physiology, of the parts observed by anatomical research. He believed that, to this end, vivisection of animals could be particularly useful (Vesalius 1543a). One of Vesalius’ discoveries, accomplished in the second edition of the Fabrica, is very significant in this respect. In the first edition, Vesalius did not deny the patency of the interventricular septum, however he seemed to be, at least, doubtful: “Thus we are compelled to astonishment at the industry of the Creator who causes the blood to sweat from the right ventricle into the left through passages which escapes our sight” (Vesalius 1543a).

In the second edition, Vesalius clearly denied this structure: “However much the pits may be apparent, yet none, as far as can be comprehended by sense, passes through the septum of the heart from the right ventricle into the left […] although they are mentioned by professors of anatomy since they are convinced that blood is carried from the right ventricle to the left. As a result – as I shall declare more openly elsewhere – I am in no little doubt regarding the function of the heart in this part” (Vesalius 1555).

The last part of this quotation is significant as it expresses the idea that a new physiology of the heart was emerging (Pagel 1964). In another passage of the Fabrica this idea became explicit: “In presenting reasons for the construction of the heart and the use of the parts I have in large degree fitted my discourse to the teachings of Galen, not because I believe them to be in entire agreement with the truth, but because I am yet hesitant to present a completely new use and function for those parts” (Vesalius 1555).

If the blood could not pass from right to left ventricle through interventricular septum, it was necessary to think of an alternative pathway, otherwise the fact that arteries filled up with blood would have been inexplicable. Note that this was necessary even in the absence of a circulatory theory of the cardiovascular system, such as in Galen's and Vesalius’ times. For them, blood was produced by the liver and reached the right side of the heart by the vena cava. The pulmonary artery, which was conceived to nourish the lungs with blood, originated from the right ventricle. Therefore, it was necessary that blood passed to the left ventricle, from which the aorta could nourish many other parts of the body and, in Galen's physiology, could distribute the vital spirit.

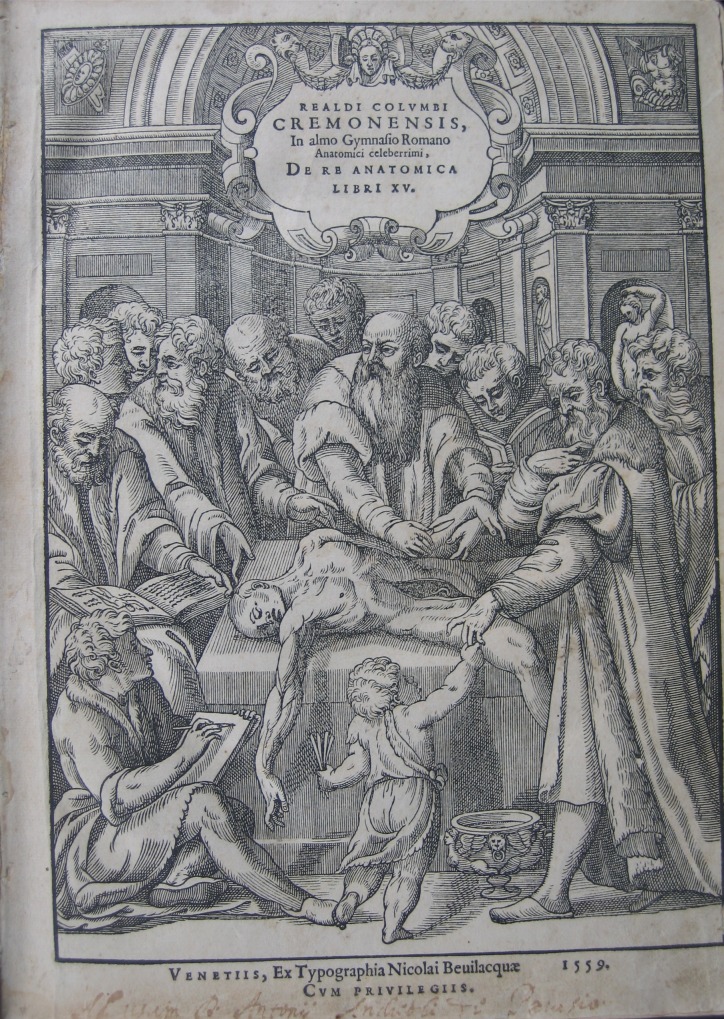

It was therefore not by chance, that pulmonary circulation was later discovered by Realdo Colombo (1516–1559), one of Vesalius’ students, in his De re anatomica (Colombo 1559; Elmaghawry et al. 2014) (Figure 21). Colombo, in fact, was the successor of Vesalius at the chair of Surgery and Anatomy in Padua. It is probable that the doubts and suggestions of his master pushed Colombo to find a solution: “I believe […] the function of the pulmonary vein is to lead blood mixed with air from the lungs to the left ventricle of the heart […] if you observe cadavers as well as living animals, you will always find the pulmonary vein full of blood, which is not possible if this vein was to carry only air and fumes” (Colombo 1559). Pulmonary circulation, in turn, was the starting point to think about systemic circulation and, again, this is related to Padua, because it was discovered by William Harvey (1578–1657) (Figure 22) who was a student in Padua, where he graduated in 1602. Harvey explicitly declared his debt to Padua Medical School (Ongaro et al. 2006).

Figure 21.

Frontispiece of Realdo Colombo's De re anatomica (1559) with a portrait of Colombo, at the center, doing the dissection.

Figure 22.

One of the most famous portraits of William Harvey, now displayed at the Royal College of Physicians in London.

This extraordinary sequence of discoveries, which brought a complete rethinking, not only of human anatomy, but also of human physiology, started with Vesalius and his revolution in anatomy. This means that the change made by him was so deep to involve not only his discipline, but also all medical sciences, exactly because was based on a new method of doing research in medicine and, more in general, on a new cultural approach toward nature.

Nullius in verba

(Take nobody's word for it)

- Motto of the Royal Society

References

- 1.Bacon F. Novum organum scientiarum. Leiden: Ex officina A. Wyngaerden & F. Moiardus; 1620. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berengario da Carpi. Isagogae breves perlucide ac uberrime in anatomia humani corporis […] Bologna: Per Benedictum Hectoris Bibliopolam Bononiensem; 1523. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colombo R. De re anatomica. Venice: Ex typographia Nicolai Bevilacquae; 1559. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cushing W. A bio-bibliography of Andreas Vesalius. New York: Archon Books; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eftekhari K, Choe CH, Vagefi MR, Eckstein LA. The last ride of Henry II of France: Orbital injury and a king's demise. Surv Ophthalmol. 2015;60:274–278. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elmaghawry M, Zanatta A, Zampieri F. The discovery of pulmonary circulation from Imhotep to William Harvey. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2014;2:103–116. doi: 10.5339/gcsp.2014.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hazard J. Jan Stephan Van Calcar, a valuable and unrecognized collaborator of Vesalius. Hist Sci Med. 1996;4:471–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mondino. Anathomia Mundini. Padua: Pietro Maufer; 1475/1476. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Murdoch JE. The analytic character of late medieval learning: Natural philosophy without nature Roberts LD, ed. Approaches to nature in the middle ages New York: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies; 1982. 171 213 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nutton V. Vesalius revised. His annotations to the 1555 Fabrica. Med Hist. 2012;56:415–443. doi: 10.1017/mdh.2012.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olry R. Andreas Vesalius on the Preparations of Osteological specimens. J Int Soc Plastination. 1998;13:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Malley C. The anatomical sketches of Vitus Tritonius Athesinus and their relationship to Vesalius's Tabulae anatomicae. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 1958;13:395–397. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/xiii.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Malley C. Andreas Vesalius of Brussels. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ongaro G, Rippa Bonati M, Thiene G, editors. Harvey a Padova. Treviso: Edizioni Lint; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pagel W. Vesalius and the pulmonary transit of venous blood. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 1964;XIX:327–341. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/xix.4.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Premuda L. Il significato del soggiorno padovano di Andrea Vesalio. Acta Med Hist Patav. 1963–1964;10:119–132. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Premuda L. Andrea Vesalio. Prefazione alla “Fabbrica” e lettera a G. Oporino. Padua: La Garangola; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Premuda L, Ongaro G. I primordi della dissezione anatomica in Padova. Acta Med Hist Patav. 1965–1966;12:117–142. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saunders JB, O'Malley CD. The illustrations from the works of Andreas Vesalius of Brussels. Cleveland and New York: The world publishing company; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabin SC. A prelude to modern science: Being a discussion of the history, sources and circumstances of the ‘Tabulae anatomicae sex’ of Vesalius. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suy R, Forneau I. Vesalius’ experience with Aortic Aneurysm. Acta Chir Belg. 2015;115:91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Telesio B. De rerum natura, iuxta propria principia. Naples: Apud Horatium Saluianum; 1586. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thiene G, Zampieri F. Il cuore di Leonardo. Atti e Memorie dell'Accademia Galileiana di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti – Parte II: Memorie della Classe di Scienze Matematiche, Fisiche e Naturali. 2013;CXXV:93–119. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vesalius A. Tabulae anatomicae sex. Venice: Sumptibus Ioannis Stephani Calcarensis; 1538. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vesalius A. De humani corporis fabrica libri septem. Basle: Ex officina Joannis Oporini; 1543a. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vesalius A. De humani corporis fabrica librorum epitome. Basle: Per Ioannem Oporinum; 1543b. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vesalius A. De humani corporis fabrica libri septem. Basle: Per Ioannem Oporinum; 1555. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zampieri F, Basso C, Thiene G. Andreas Vesalius’ Tabulae anatomicae sex (1538) and the seal of the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Card. 2014;63:694–695. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zampieri F, Zanatta A, Elmaghawry M, Rippa Bonati M, Thiene G. Origin and development of modern medicine at the university of Padua and the role of the “Serenissima” Republic of Venice. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2013;21:1–14. doi: 10.5339/gcsp.2013.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]