Abstract

Aim

The aim of this study was to evaluate the National Institute of Health (NIH)-funded PRIDE Institute in Behavioral Medicine and Sleep Disorders Research at New York University (NYU) Langone Medical Center. The NYU PRIDE Institute provides intensive didactic and mentored research training to junior underrepresented minority (URM) faculty.

Method

The Kirkpatrick model, a mixed-methods program evaluation tool, was used to gather data on participant’s satisfaction and program outcomes. Quantitative evaluation data were obtained from all 29 mentees using the PRIDE REDcap-based evaluation tool. In addition, in-depth interviews and focus groups were conducted with 17 mentees to learn about their experiences at the institute and their professional development activities. Quantitative data were examined, and emerging themes from in-depth interviews and focus groups were studied for patterns of connection and grouped into broader categories based on grounded theory.

Results

Overall, mentees rated all programmatic and mentoring aspects of the NYU PRIDE Institute very highly (80–100%). They identified the following areas as critical to their development: research and professional skills, mentorship, structured support and accountability, peer support, and continuous career development beyond the summer institute. Indicators of academic self-efficacy showed substantial improvement over time. Areas for improvement included tailoring programmatic activities to individual needs, greater assistance with publications, and identifying local mentors when K awards are sought.

Conclusions

In order to promote career development, numerous factors that uniquely influence URM investigators’ ability to succeed should be addressed. The NYU PRIDE Institute, which provides exposure to a well-resourced academic environment, leadership, didactic skills building, and intensive individualized mentorship proved successful in enabling URM mentees to excel in the academic environment. Overall, the institute accomplished its goals: to build an infrastructure enabling junior URM faculty to network with one another as well as with senior investigators, serving as a role model, in a supportive academic environment.

Keywords: PRIDE, Mentorship, Training, Workforce diversity, Sleep, Behavioral medicine

1. Introduction

Consistent with the goals of Healthy People 2020 is the need for a well-trained and diverse workforce of physicians and scientists [1]. This is essential to foster implementation of innovative health models to address pressing health conditions in the US population. Underdiagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders, particularly in minority communities [2–7], constitutes one of those health crises, necessitating trained investigators to implement appropriate translational models to tackle them. This was recently recognized by the Institute of Medicine, issuing this widely cited report “Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem” [8]. Evidence strongly suggests that communities in greatest need of sleep health information are in effect the ones exhibiting poorest awareness of sleep deficiencies and related adverse effects on health and quality of life [9–11].

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) sponsored workshop “Reducing Health Disparities: The Role of Sleep Deficiency and Sleep Disorders” highlighted the need to implement translational models to address sleep-related cardiovascular risk in disparity communities [12]. Workshop attendees expressed concern over the limited academic workforce of underrepresented minority (URM) faculty investigating various barriers (eg, financial, geographic, and sociocultural) hindering adoption of healthful sleep practices [4,13,14]. A well-trained workforce of URM faculty is essential in the field of sleep medicine, because members of the URM faculty are more likely to engage in research to reduce health disparities in underserved and/or low-income communities [15,16]. Unfortunately, increasing diversity in the academic workforce has remained a daunting challenge [17]. This is compounded by evidence that so few URM investigators receive K awards, which are fundamental in launching a successful academic career [18]. Moreover, a recent study indicated an alarming racial gap in NIH grant awards, finding that black scientists were 13% less likely to receive NIH funding relative to their white counterparts [19]. Thus, implementing training programs tailored to address specific needs of URM scientists is paramount in empowering them to address sleep-related cardiovascular diseases that disproportionately burden their communities.

The Program to Increase Diversity in Behavioral Medicine and Sleep Disorders Research is a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded training institute at New York University (NYU) Langone Medical Center (NYU PRIDE) focusing on one of the seven recommendations highlighted at the workshop: to mentor a new cadre of URM investigators pursuing independent academic careers in sleep research [20]. The NYU PRIDE Institute was founded on the belief that increasing the recruitment and retention of URM faculty is achievable via a sustained effort to maximize exposure to career development opportunities and promote interactions with seasoned mentors in a supportive academic network [18,21–24]. This is crucial in increasing mentees’ academic success at all levels of health-related fields [25]. Briefly, NYU PRIDE exposes junior URM mentees to mentored learning opportunities intended to inspire them to conduct research in sleep health disparities using innovative translational behavioral models.

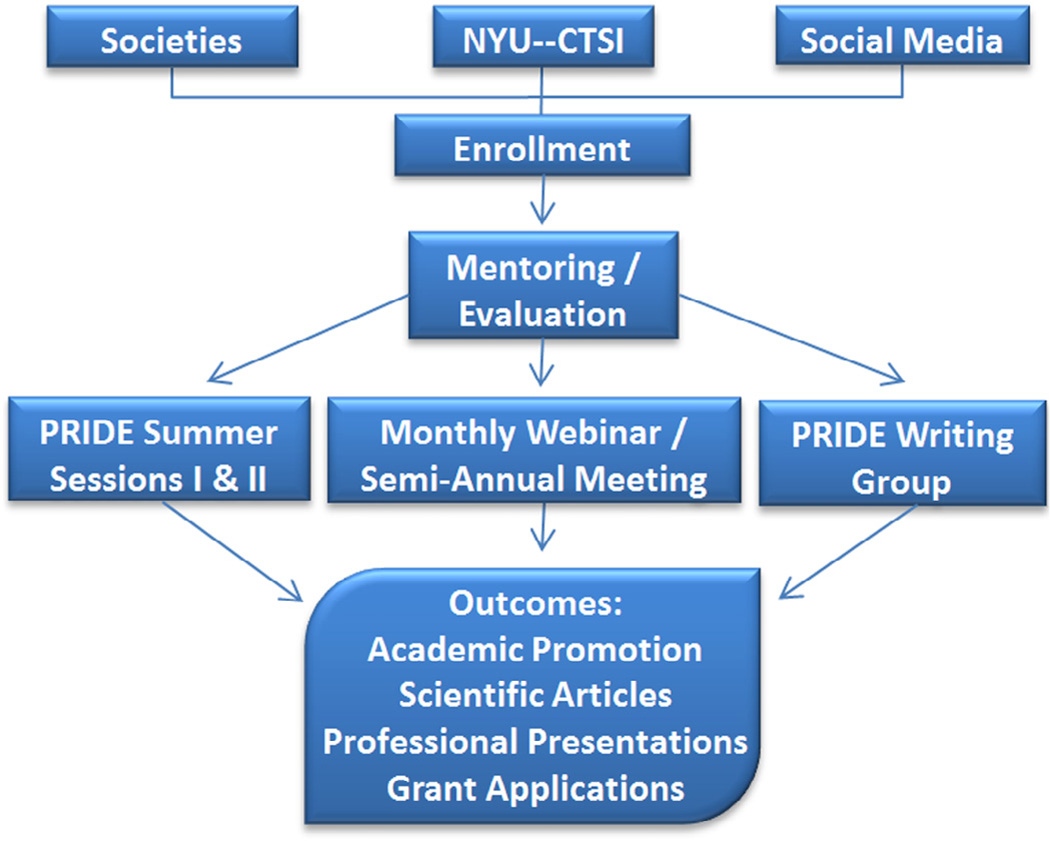

The specific goals of the institute are to: (1) select qualified junior URM faculty with potential to contribute to the current knowledge of translational models to reduce sleep-related cardiovascular risk; (2) increase mentees’ knowledge, skills, and motivation to pursue a career in the implementation of translational behavioral sciences; (3) provide continuous mentorship to mentees and facilitate achievement of career independence; and (4) dispense individualized coaching in acquiring proficiency in grant writing and understanding of the NIH review process. Matriculated URM scholars attend a 2-week didactic program (Summer I) at NYU, followed by ongoing consultation with a mentorship team; a mid-year meeting; monthly webinars, and attend a 1-week NIH proposal-focused program (Summer II). Briefly, during Summer I scholars participate in workshops and seminars on various topics including responsible conduct of research, biostatistics, epidemiology, research methodology, grant writing, and topics on behavioral medicine and sleep disorders and circadian rhythm research. During Summer II, they participate in NIH mock study sections with peer proposal critiques and one-on-one interactions with NIH program staff (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Description of the four components of the NYU PRIDE Institute’s training/mentoring plan.

| Programmatic Components of the NYU PRIDE Institute |

|---|

|

Fig. 1.

Organizational structure of the NYU PRIDE Institute. Candidates are recruited from multiple sources (scientific societies, social media, and NYU centers). They receive continuous mentorship while participating in various didactic activities (Summer sessions, monthly webinars, and mid-year meeting). They also participate in program evaluation (quantitative and qualitative) to assess program effectiveness in achieving PRIDE academic goals.

1.1. Theoretical underpinnings and impediments to success

The NYU PRIDE Institute is consistent with the broad, trans-NIH strategy to promote diversity in the academic workforce [18]. The overarching goal of the institute is to implement and evaluate innovative approaches to improve capacity to mentor URM faculty for successful academic careers focusing on sleep-related cardiovascular diseases [20]. In contrast to non-theoretically grounded training programs, the programmatic components of the institute were conceived based on well-established social science models, Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior [29] and Bandura’s social cognitive theory [30,31]. The training and mentoring curriculum was designed to empower junior URM faculty to develop successful careers through enhanced academic self-efficacy, an important motivator of academic success.

The institute, which has been in existence for four years (2010–2014), was developed by a team of established investigators and educators with established track record in training and mentoring URM scientists [20]. Its programmatic components (Table 1) are anchored by Uri Treisman’s observations of URM scientists and the Ibarra–Thomas theory that URM scientists need adequate mentorship to succeed academically [26–28]. Its components also draw from the NIH Oversight Committee’s report that mentoring was the most valuable feature of training programs [18]. Finally, they are informed by evidence suggesting that URM faculty are not routinely exposed to experiences and opportunities needed to succeed in academia [32]. While developing the initial programmatic components, the NYU PRIDE leadership considered evidence that URM scientists often encounter enormous challenges in navigating through the academic ladder to achieve independence. For example, being the only URM faculty in a department is often viewed as an isolating experience, with some reporting feeling pressured to succeed with very little support. Occasionally, some report enduring the “imposter syndrome,” a lingering feeling that they do not deserve their professional status or achievements [33] or may be laden by “stereotype threat,” the experience of anxiety or concern in a situation where they have the potential to confirm a negative stereotype about their social group [34,35]. Mentors in the NYU PRIDE Institute are aware of such challenges and impediments to success, hence the decision to implement individualized mentorship to promote career development of junior URM faculty [20,21,26–28,36]. To empower junior URM investigators to reach academic career goals constitutes the cornerstone of the NYU PRIDE experience.

1.2. Overview of program evaluation for the NYU PRIDE institute

In consort with the PRIDE Coordination Center (http://www.biostat.wustl.edu/pridecc/), the leadership team evaluates the NYU PRIDE Institute’s programmatic components and tracks mentees’ progress yearly for five years post program completion. Specific measurable outcomes include: (1) number of professional presentations and peer-reviewed publications; (2) academic leadership positions held; (3) academic career awards; and (4) submitted and/or funded federal and nonfederal grants. Program evaluation includes two aspects: (1) the processes used to achieve the institute’s goals and (2) the outcomes of the training and mentorship that mentees received [37,38]. Principles underlying program evaluation were considered in designing the institute (Table 2), choosing methods for identifying qualified mentees (Table 3), developing a sustainable mentoring infrastructure, monitoring didactic activities, and assessing impact on mentees’ career development [39]. The program evaluation focuses on examining effectiveness of the institute in reaching its specific goals and ascertaining mentees’ satisfaction with the institute, its content areas, instructional quality, and academic environment using both quantitative and qualitative assessment tools.

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of the Kirkpatrick model.

| The Four-Level Kirkpatrick Model | |

|---|---|

| Level 1: Reaction– to what degree participants reacted favorably to programmatic, didactic, and mentoring sessions. | Measured by:

|

| Level 2: Learning – to what degree participants acquired the intended knowledge, skills, and attitudes based on their participation in the institute. | Measured by:

|

| Level 3: Behavior – to what degree participants applied what they learned during the institute after they returned to their home institutions. | Measured by:

|

| Level 4: Results – to what degree targeted outcomes were observed as a result of participating in the institute and subsequent reinforcement. | Measured by:

|

Table 3.

Description of the five criteria utilized to select qualified candidates for the NYU PRIDE Institute.

| Domains used to Evaluate PRIDE Candidates | |

|---|---|

| Track Record | Creativity of the candidate and ability to work in a multidisciplinary environment; this includes area of expertise and previous training experience, teaching, funded grants, publications, and scientific presentations. |

| Research Plan | Scientific merit, significance to the field, potential clinical importance, and feasibility of the proposed research plan or hypothesis to be tested. |

| Training Plan | Quality and appropriateness of proposed mentors and advisors and time commitment to interact with the mentoring team. |

| Resources | Institutional commitment and resources available to develop and complete proposed research projects and suitability of the available clinical and laboratory infrastructure. |

| Career Potential | Likelihood that candidate will develop a career as an outstanding investigator and have an important impact in their respective field on behavioral medicine in particular. |

The PRIDE leadership team works directly with the Data Coordination Center to acquire quantitative data using the PRIDE REDcap-based evaluation tool, allowing constant updating of contact information, academic successes (eg, promotions, presentations at scientific meetings, peer-reviewed publications, and status of submitted grants). This automated system makes the PRIDE program evaluation an iterative process, providing useful data to improve varying aspects of the institute as well as monitoring mentee’s progress. The PRIDE leadership team also works closely with an external evaluator to acquire qualitative data (process evaluation) through focus groups and in-depth interviews with the trainees.

The qualitative evaluation reported in this paper consists of two parts. First, at the end of the institute, the evaluator met with mentees to discuss their perceptions of the instructional quality of didactic sessions, the academic environment, and the mentorship plan. Those meetings used the focus group format and in-depth interviews, eliciting useful comments about the institute’s strengths and weaknesses. Second, the program evaluator analyzed emergent themes from the focus group and individual interview data to write a final evaluation report describing the achievements of the institute and areas that may need improvement.

In this paper, the NYU PRIDE Institute evaluation results are discussed incorporating both quantitative data collected by the Data Coordination Center and qualitative data gathered during focus groups and in-depth interviews by an external evaluator using Kirkpatrick’s model (see Methods section). Consistent with previous research, a particular focus was placed on indices of academic self-efficacy, as they strongly predict academic success; the contribution of mentorship, a key ingredient in academic success, was also assessed. While ascertaining academic success would require a minimum of two years post completion, our discussion is focused on preliminary results relevant to mentee’s satisfaction with the institute’s programmatic components in addition to their academic success contrasting two specific outcomes (number of publications and grant awards) before matriculation, during, and upon program completion. The following elements of the institute’s programmatic activities were the focus of program evaluation: Summer I sessions, mid-year meeting, monthly webinars, and Summer II sessions.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

From 2010 to 2014, a total of 29 URM mentees from 15 US institutions were selected for participation in the NYU PRIDE Institute using predetermined criteria (Table 3). All 29 mentees (female = 66%; black = 79%, Hispanic = 17% and white (with disability) = 4%), trained in three successive cohorts, provided quantitative data using the web-based evaluation system (Table 2). In addition, of the 29 mentees, 17 (female = 65%; four mentees from Cohort 1, four from Cohort 2 and nine from Cohort 3) participated in in-depth interviews and three focus groups, which were conducted after the last Summer Session II in July 2014. All 29 PRIDE mentees were invited to participate in both the in-depth interviews and the focus groups, but 12 of them could not participate due to logistical challenges. Otherwise, all matriculated scholars completed all phases of the training and mentoring institute (see Table 4 for demographic characteristics).

Table 4.

Background characteristics of mentees (n = 29) in the NYU PRIDE Institute upon matriculation. All participants completed all phases of the PRIDE Institute.

| Characteristics of Mentees in the NYU PRIDE Institute | |

|---|---|

| Variable | % |

| Gender (% male) | 34 |

| Degree | |

| MD | 34 |

| PhD, EdD, etc. | 59 |

| Combined MD/PhD | 7 |

| Faculty Rank (at time of application) | |

| Instructor | 24 |

| Assistant Professor | 66 |

| Associate Professor | 10 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | |

| Black | 79 |

| Hispanic | 17 |

| White (with disability) | 4 |

2.2. Procedures

Kirkpatrick’s model (1959), the most widely used goal-based evaluation method, is the basis for the NYU PRIDE Institute evaluation plan [40]. This model relies on both quantitative and qualitative data to determine the extent to which the institute achieved expected outcomes (Table 2). The evaluation plan for the NYU PRIDE Institute used a mixed-methods design to generate both formative data (feedback provided throughout the institute to improve instructional quality) and summative data (evidence that learning has occurred) [41]. This model is used extensively in health and health education evaluation research. The evaluation plan addressed four specific outcomes using two data sources: in-depth interviews and focus groups as well as online survey data.

In Kirkpatrick’s four-level model, each successive evaluation level is built on information provided by the lower level. Its four levels are defined as follows: (1) Reaction Outcomes: Online surveys with rating scales were completed at the conclusion of summer training sessions to assess mentees’ satisfaction level. Data were collected and analyzed to determine the perceived benefits and feedback regarding all programmatic components. In addition, focus groups were conducted to gather feedback on mentees’ experiences. (2) Learning Outcomes: In-depth interviews and focus groups were conducted to assess mentees’ acquisition of research skills and professional development. Particular focus was placed on understanding the benefits of the mentee/mentor relationships in ensuring mentees’ success. (3) Behavior Change Outcomes: Mentees’ research activities were provided via the web-based evaluation tool and analyzed. In-depth interviews provided data on perceived changes in research skills and abilities that mentees directly attributed to the PRIDE Institute. (4) Impact Outcomes: Data from all phases of the institute were analyzed to determine the impact of training and mentoring on mentees’ academic activities, peer-reviewed manuscripts, and submitted/funded proposals.

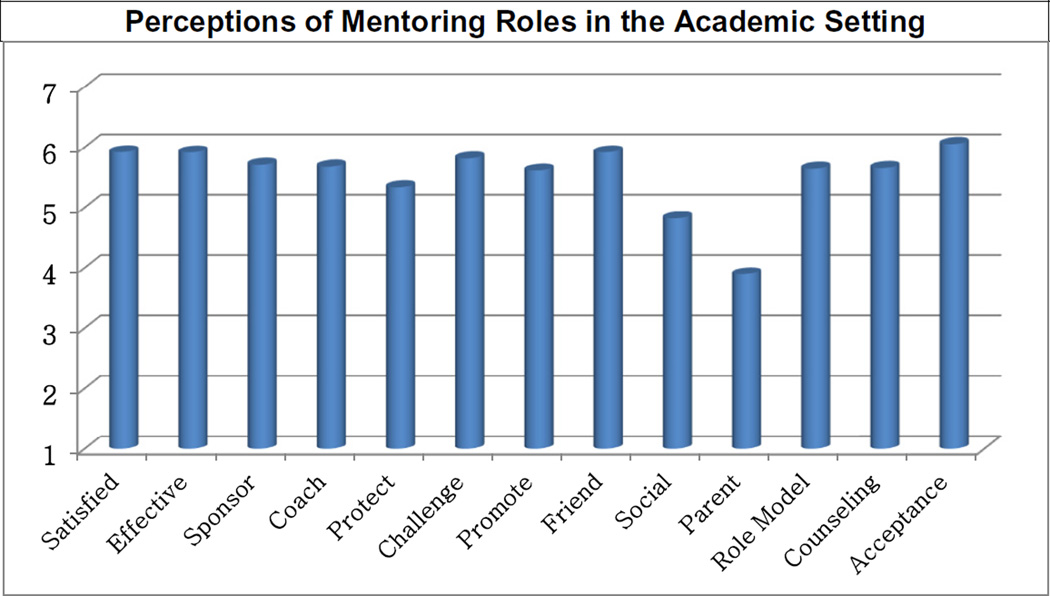

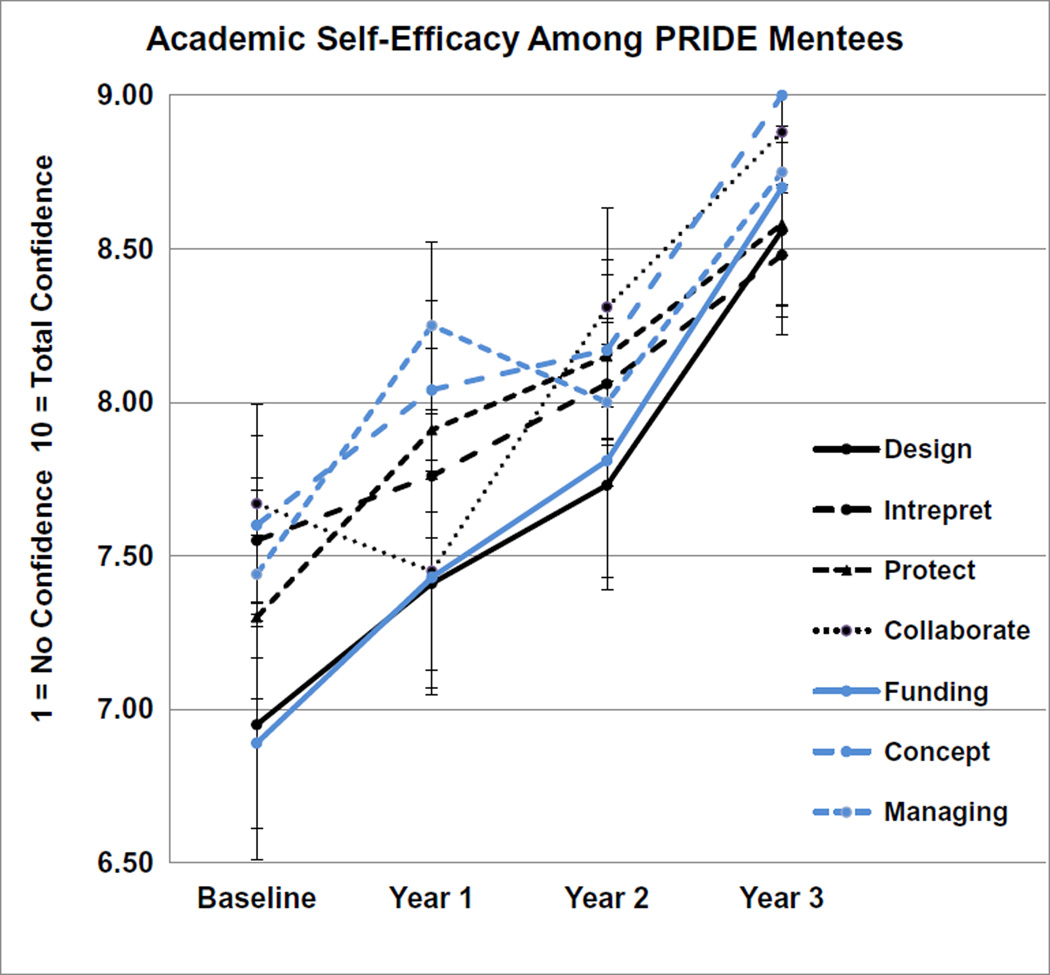

Mentees were also asked to provide subjective ratings of satisfaction with the mentor–mentee relationship and level of self-efficacy using two well-validated instruments: the Ragins and McFarlin Mentor Role Instrument (RMMRI) and the Clinical Research Appraisal Inventory (CRAI). The RMMRI is a 33-item, Likert-scale instrument focusing on perceptions of five mentoring roles in the following career dimensions: (sponsor, coach, protector, challenger, and promoter) and six mentoring roles in the psychosocial dimensions: (friend, social associate, parent, role model, counselor, and acceptor). Scores ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) (Cronbach’s α = 0.82–0.97). The CRAI is a 68-item, Likert-scale survey measuring self-efficacy in the academic setting [42]. Items are scored from 0 (no confidence) to 10 (total confidence) and are used to derive seven factor scores, referred to as indicators of academic success (design, interpret, protect, collaborate, funding, conceptualize, and manage) (Cronbach’s α > 0.85) [43]. Table 5 presents a complete description of the factor structure for the CRAI. These two measures were chosen because of their strong association with a likelihood of experiencing long-term academic success [23–25].

Table 5.

CRAI was administered to all URM scholars to assess trends in academic self-efficacy over time (2010–2014).

| Factor Structure for the Clinical Research Appraisal Inventory | |

|---|---|

| Factor | Description |

| Design | 19 questions: designing, collecting, recording, and analyzing study data |

| Interpret | 16 questions: interpreting, reporting, and presenting study data |

| Protect | 10 questions: protecting subjects and in responsible conduct |

| Collaborate | 8 questions: identifying, initiating, generating, sustaining, and terminating effective collaborations |

| Funding | 7 questions: identifying funding sources, preparing proposals, budget time, and writing grants |

| Conceptualize | 6 questions: conceptualize topic, refine problem, organize proposal, articulate, and justify |

| Manage | 2 questions: managing project, maintaining activity log, and preparing reports |

2.3. Data analysis

Frequency and measures of central tendency were used for summarizing sample characteristics. Survey data from each cohort were combined and analyzed to assess mentees’ overall satisfaction with various programmatic components. Interviews were audio-recorded and précis were created for each interview. Focus groups were also audio-recorded, and detailed notes were taken during each group discussion. The evaluator transcribed focus group data and performed multiple readings of the transcript. The précis and transcripts were entered into Dedoose, a qualitative data management software. These were then analyzed for key phrases, themes, and examples.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative evaluation data

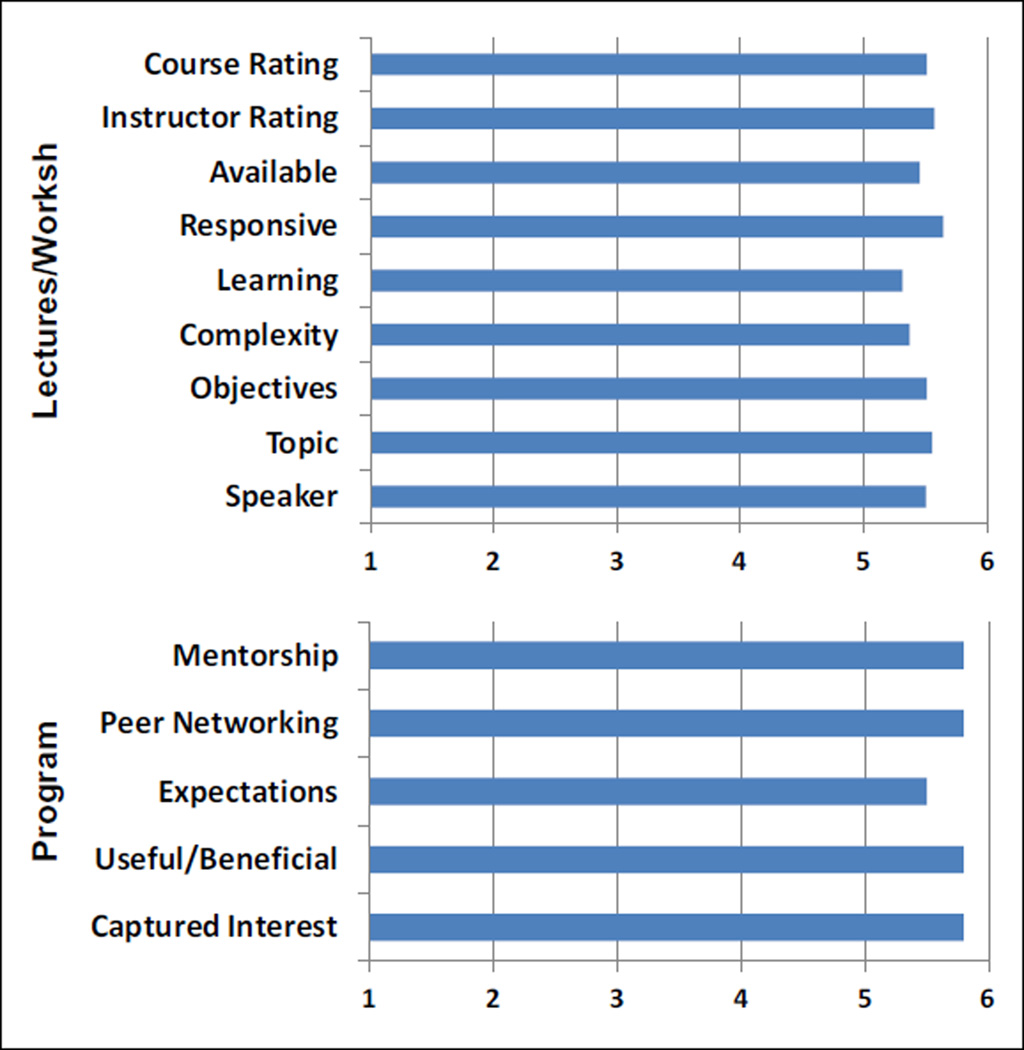

3.1.1. Programmatic activities

As shown in Fig. 2, participants consistently rated lectures as effective and the topics as interesting. The majority (80–100%) of the participants agreed that lectures were effective, interesting, and accomplished their objectives. They also indicated that materials were presented in a clear and organized manner, and that the complexity level was appropriate. The majority of the participants were very satisfied with the performance of the presenters, with the quality of the seminars and workshops offered during summer sessions. Most also indicated that the programming for summer sessions met their expectations, were beneficial, and captured their interest; that mentorship was appropriate; and that networking opportunities were available. As illustrated in Fig. 3, mentees rated their perception of the mentor–mentee relationship very favorably.

Fig. 2.

Quantitative evaluation data provided by mentees in all three cohorts (n = 29) during post-summer evaluations. Mentees were asked to rate degree of satisfaction with various programmatic aspects of the institute (e.g., lectures, workshops, and structural elements); scales ranged from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 6 (very satisfied). A full description of rating scales is available on our website [20].

Fig. 3.

Summary of data obtained with the Ragins and McFarlin Mentor Role Instrument (RMMRI) from mentees in all three cohorts (n = 29) during post-summer evaluations; scores ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Items represent perceptions of mentoring role in career dimensions (sponsor, coach, protector, challenger, and promoter) and psychosocial dimensions (friend, social associate, parent, role model, counselor, and acceptor) [42].

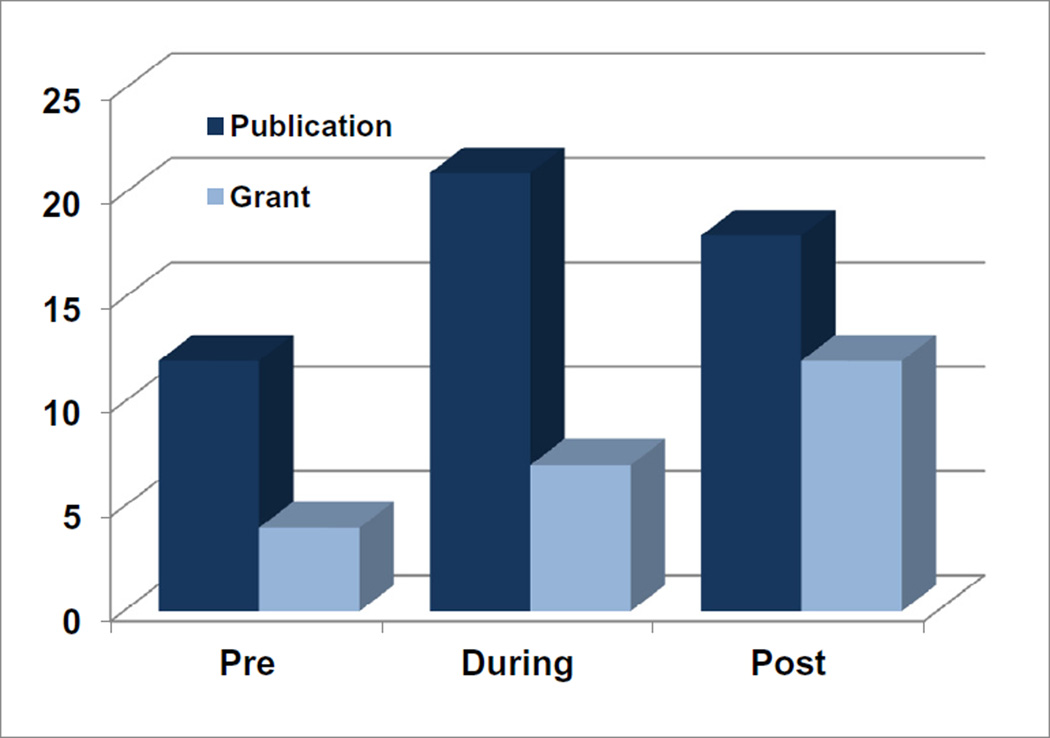

3.1.2. Peer-reviewed publications and grant awards

While NIH recommends that assessment of academic success be performed two years after completion of training programs, academic performance was evaluated for all mentees in the institute, although only the first cohort (2010–2011) met the two-year assessment timeframe. As depicted in Fig. 4, overall the number of proposals submitted to the NIH increased during and after completing the institute. In particular, five K applications (three of which were funded), four R01 applications (one of which was funded), three minority supplements (two of which were funded), and 11 applications were submitted to agencies other than the NIH (10 of which were awarded). While one recently submitted a patient-centered outcomes grant application, one submitted a T37 grant, which was awarded; two R21, one P20, and one R15 applications were funded. Similarly, the number of publications rose substantially during the training period, but decreased slightly upon completion of the institute, although greater than the number registered before the training began. Four mentees were promoted to the associate professor rank and one to the professor rank. The growth in the number of mentees submitting grant applications or publication records seems consistent with the gradual increase in indicators of academic self-efficacy depicted in Fig. 5. Indeed, all indicators of academic success exhibited gradual trends towards greater confidence. Although no control group exists to offer a valid comparison with our data, performance of PRIDE scholars regarding NIH awards ranks higher than success rates achieved by other investigators applying contemporaneously (33% vs. 17.4%; published data from NIH RePORTER).

Fig. 4.

Summary of data (i.e., number of published scientific papers and grant awards) provided by mentees in all three cohorts (n = 29) during post-summer evaluations; note that Cohort 3 had only completed 1 year of training in the institute at the time of evaluation.

Fig. 5.

Indicators of academic success among mentees (Cohort I; n = 9) in the NYU PRIDE Institute using data from the Clinical Research Appraisal Inventory (2010–2014); indicators were derived from initial factor analyses yielding seven factor scores (design, interpret, protect, collaborate, funding, conceptualize, and manage) [43].

3.2. Qualitative evaluation data

The evaluator transcribed qualitative data and performed multiple readings of the transcript yielding several important themes as follows: realities of academic research for URM scientists, importance of research skills and professional training, the PRIDE effect, and importance of mentorship. All scholars were adamant about their principal objective to pursue a career in health disparities research, with 85% developing or conducting sleep health disparities research; others focused primarily on behavioral medicine and considered sleep as a secondary outcome measure. Table 6 presents recommendations for improved program structure based on process data. Table 7 presents relevant quotes supporting these broad categories.

Table 6.

Recommendations for improved program structure based on process data.

| Activity | Pre-Program | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career Development | Summary of career goals and proposed research plan Track non-sleep researchers and sleep researchers Tailored career goals based on strengths and weaknesses |

Career planning/development and goal setting | ||

| Mentoring | Establishing/developing/nurturing mentoring relationships One-on-one and group mentorship meetings with PRIDE team |

|||

| Team Building/Collaboration | Meet-and-greet webinar Statistical analysis webinar Peer mentoring |

Mentee presentations | Collaboration support | Becoming a mentor |

| Workshops with URM scientists and faculty | ||||

| Didactic Skills Training | Reading list Course management tool (i.e., blackboard) Assessment of mentee’s needs, strengths, and weaknesses |

Didactic training-sleep medicine, research methods, mixed methods, digital storytelling, epidemiology Opportunities for advanced training/webinars |

NIH visits | Webinars Conferences |

| Publishing | Introduction to publishing and grant writing; PRIDE data sets Assign writing-group facilitators |

Publication workshops/Publication calendar | Deadlines | Continued collaborations |

| Grant Writing | Developing ideas and research agenda | Webinars Feedback Deadlines |

Submission/resubmission | Post grant decisions Developing new ideas |

Table 7.

Emergent themes from qualitative evaluation data: quotes from PRIDE participants.

| Categories | Relevant Quotes |

|---|---|

| Realities of Academic Research for URM Scientists |

|

| The PRIDE Effect |

|

| Research Skills and Professional Training |

|

| Importance of Mentorship |

|

3.3. Realities of academic research for URM scientists

Participants spoke of numerous challenges in meeting their daily academic responsibilities. They indicated that challenges they faced were fundamentally different in comparison to those experienced by non-URM colleagues. They mentioned the added burden of being the only URM faculty member created an additional layer of pressure; those with both clinical and research responsibilities felt “mired down” by the work at times. For some, this resulted in feeling distracted and unable to focus on developing their research agendas. Table 7 presents the relevant quotes from several participants.a,b,c,d

Participants also indicated their role as URM researchers were unique, in that they were personally invested in their research topic. One mentee intimated that her career advancement was directly linked to whether or not she could directly improve communities of color in some way. She thought it important that minority researchers be able to have conversations about how to grow their career while supporting the people they are trying to help. She went on to say that her concern was that they do not talk about their work in terms of scholarship and service; they talk about it in terms of dollars. Another mentee agreed and questioned non-URM researchers’ motives for studying health disparities.e

Others commented on feeling isolated and misunderstood in their work environment and mentioned that although race was not a direct issue it is something they feel. Others agreed and thought the isolation hindered their productivity. This mentee indicated that being detached from colleagues and her department affected her work. For her, participation in PRIDE helped her combat feelings of marginalization.f

3.4. The PRIDE effect

For most mentees, the PRIDE Institute served as a welcome reprieve from their daily responsibilities. Participation in the program gave them the opportunity to step away from the normal grind and refocus.a Another scholar indicated that the institute motivated her to want to do more than treating patients. The institute rekindled her desire to conduct research in addition to clinical responsibilities.b She said that it was not just the time away that helped the participants to refocus but also the nature of the institute and the support given to the mentees that motivated them. One mentee indicated the support offered her with hope and a vision for her research.c Other participants spoke of the impact of PRIDE on their academic career development.d

This “help” was referred to as the “PRIDE effect,” a sense of unity created by the institute’s principal investigators and staff. Table 5 sums up the experience of some of the mentees. According to participants, the dedication of the PRIDE staff created an atmosphere of trust that made it easy for them to accept feedback and guidance. The institute was referred to as “a safe space to learn and make mistakes.” Of particular note was the degree to which the staff could understand the experiences of the mentees. This was mentioned repeatedly; the mentees believed this familiarity was born out of shared experiences. One participant acknowledged that mentoring programs run by non-minorities could not offer the same degree of understanding.e She went on to state that it is not about the race or ethnicity of the leaders as much as it is about their ability to understand the lived experiences of URM scientists, and their willingness to be open to acknowledge how challenging that experience can be. Not only did the PRIDE staff contribute to creating an atmosphere of acceptance, but the mentees themselves added to the safe space as well.f

3.5. Research skills and professional training

Participants commented on the institute’s structure as an asset to their professional development.a Most felt the structure helped them to gain skills and increase their productivity. The following quote demonstrates how one participant benefited from the structure of the program:

Most mentees felt their participation in PRIDE enhanced their skills.b These tools and techniques included: grant writing, networking, publishing, identifying mentors, presentation skills and developing research agendas, and long-term career plans. This participant summarized how minority faculty are often hindered by lack of opportunities.c Others agreed that PRIDE gave them access to skills and opportunities that they otherwise would not have had.d

A recurring theme was the importance of learning to “play the game.” Most participants felt their professional success was intimately tied to grant writing and publications. However, they acknowledged that both require a specific set of skills and strategies. The two comments below summarize how mentees felt about the grant-writing skills they gained as program participants.e

Participants appreciated the opportunity to develop research skills they may not have gotten otherwise. One participant enthusiastically expressed his gratitude.f He went on to clarify that the skills he obtained through participating in the PRIDE Institute increased his productivity.

3.6. Importance of mentorship

Participants often commented on the uniqueness of the mentoring relationships they formed with PRIDE Institute’s PIs. Even those who were a part of formal mentoring programs at their home institutions commented that PRIDE mentorship was different.a This commitment was demonstrated by the PRIDE staff’s willingness to share their own experiences and to engage with the mentees both one on one and in groups.b

The mentees repeatedly mentioned the importance of committed mentors who could both teach and demonstrate how to accomplish career goals. They emphasized a need for mentoring relationships that were more than just symbolic.c They indicated that the commitment of the PRIDE mentors was unique.d They intimated that the overall success of the institute was due to the quality and level of commitment of PRIDE mentors/faculty, and their commitment to mentoring the next generation of underrepresented scientists. Mentees also commented on the institute’s ability to open doors. One participant benefited greatly from an opportunity to observe a grant review panel.e

Another participant emphasized the importance of mentorship in helping URM scientists establish new research agendas.f Despite their recognition of the importance of adequate mentorship, many mentees commented on the difficulty of finding committed mentors outside of the PRIDE Institute. Some participants spent months trying to identify a mentor to no avail. They attributed their challenges to the fact that “people are so busy and can’t take on a junior mentee.” At times, PRIDE staff had to intervene to assist mentees in developing a plan to identify and find a suitable mentor. Throughout the process, mentees learned a great deal about networking and the strategic identification of others to garner support for their research initiatives. In addition, mentees found their affiliation with the PRIDE Institute to be an asset, which opened doors and piqued the interest of potential mentors.

4. Discussions

The NYU PRIDE Institute was designed to address this critical deficiency in the academic workforce [18] by training and mentoring a new cadre of URM scientists to pursue careers in sleep-related cardiovascular diseases applying innovative translational behavioral models. During the first cycle of the institute (2010–2014), 29 URM mentees successfully completed their training, establishing a network of well-trained URM scientists to lead the nation’s health disparities research agenda.

As is the case for most junior faculty, URM scientists need to acquire adequate research and professional skills and receive guidance in establishing their academic careers. However, several circumstances limit their exposure to opportunities and acquisition of such skills. These include feelings of isolation as a result of being the only minority in their department/institution and difficulty finding mentors who understand their unique challenges. Combined with traditional professional demands, these factors have the potential to derail their academic career development. Results of the NYU PRIDE Institute evaluation data demonstrated that the PRIDE model comprising intensive didactic skills training coupled with individualized mentorship by senior-level investigators proved successful in facilitating junior URM scientists to excel in the academic environment. Although mentees identified potential areas for improvement, overall the PRIDE Institute accomplished its main objective: to build an infrastructure in which URM scientists were able to launch their career in a supportive academic environment. All mentees expressed satisfaction with all programmatic components of the institute, although mentorship seems to have been the most valuable aspect of the learning experience at the PRIDE Institute (Fig. 4). All mentees had a highly favorable perception of the mentor–mentee relationship.

Consistent with the Kirkpatrick’s model for program evaluation [40], requiring use of both quantitative and qualitative data, the institute achieves expected outcomes (Table 2). Successes were noted at all four levels of evaluation. With regard to reaction outcomes, analysis of online survey data revealed that the majority of the scholars agreed that lectures were effective, interesting, and accomplished their objectives. Most mentees were highly satisfied with the performance of the presenters as well as with the quality of summer seminars and workshops. Most also indicated that mentorship was appropriate and that networking opportunities were available, contributing to their renewed interest and motivation to pursue an academic career. This may explain why the number of NIH awards increased during and after completing the program in the institute. It is also noteworthy that the number of publications rose substantially during the training period. That the number of publications dipped slightly upon completion of the program in the institute may be elucidated by a greater focus on grant application development and submission, a key expectation pervading all aspects of the training and mentoring curriculum to which they were exposed.

Analysis of quantitative and qualitative data demonstrated that mentees reported important learning outcomes. Both quantitative and qualitative data converge in showcasing that participation in the PRIDE Institute allowed mentees to develop new skill sets or enhanced writing and career development skills that advanced mentees already possessed. These are exemplified in the following statements: “If I didn’t have PRIDE, I probably wouldn’t learn some of the new tools and techniques I’ve learned.” “[I’ve gained] skills to communicate my scholarly ideas in a clear and precise way … in a way that highlights my own strengths.” “Before PRIDE I believe I had just on published paper. Since then, I have co-led six papers and I’m on four others, and this has happened in the space of a year.”

Participation in the institute also led to important behavior changes. This is perhaps most notable in the desire to focus on a particular health disparity problem, to succeed in conducting academic research, and to serve as mentors to other junior URM scientists. According to mentees, the dedication of the PRIDE staff created an atmosphere of trust that made it easy for them to accept feedback and guidance. One scholar sums it up this way: “In this program, I get feedback from people I know and trust. It forces me to go back and improve.” In-depth interview data showed positive changes in their confidence to succeed in academia and make a difference in their own community. Furthermore, data from all aspects of the institute showed enormous impact of training and mentoring mentees received as observed in improved self-efficacy (Fig. 5), which may have led to the development of innovative research ideas and increases in peer-reviewed publications, submitted/funded proposals, and academic promotions. Unfortunately, the direct link between self-efficacy and academic success could not be established because of inadequate power and insufficient time to assess adequately the full impact of the training institute for all mentees, as a minimum of two years is required to make that determination [18]. We believe that exposure to the PRIDE Institute enables junior URM faculty to develop important research and leadership skills to compete nationally for funding to support their academic career. Although benefits of participating in the PRIDE Institute could not be fully ascertained, it seems evident that they would be substantial judging from initial success by the advanced scholars (Cohort I). We also expect that others would also demonstrate their ability to obtain external funding to support their research as they gain greater self-efficacy over time [30,31]. Future studies are warranted to assess whether the pressure of securing tenure and promotion, commonly experienced by junior scholars, may have also played a motivating role in increased academic success measured in terms of number of grants and peer-reviewed papers.

4.1. Recommendations

Although mentees were highly satisfied with all programmatic components of the NYU PRIDE Institute, a few recommendations for improvement were made (see Table 6). The most frequently mentioned recommendation was the establishment of a program management tool (eg, blackboard), providing them with access to everything they need to benefit fully from participating in the institute, including preprogram reading materials and expectations and guidelines for each component (ie, Summer I sessions, midyear meeting, monthly webinars, and Summer II sessions). Another important recommendation was the establishment of a step-by-step protocol for identifying external mentors and negotiating a mentoring relationship. Participants wanted a mechanism facilitating duplication of their PRIDE-mentoring relationships with mentors at their home institutions. Mentees also indicated that the institute should offer support beyond the PRIDE academic year [40].

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the NHLBI (R25HL105444). The authors thank the PRIDE mentors and speakers who have contributed to the development and implementation of the PRIDE curriculum and who have held summer workshops and seminars. They also thank all the mentees who have provided valuable feedback and evaluation data enabling constant refining of the curriculum, leading to improvement in all PRIDE programmatic components.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

The ICMJE Uniform Disclosure Form for Potential Conflicts of Interest associated with this article can be viewed by clicking on the following link: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2015.09.010.

References

- 1.Healthy People. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. Healthy People 2020 objectives. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ancoli-Israel S, Klauber MR, Stepnowsky C, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in African-American elderly. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1946–1949. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gottlieb DJ, Whitney CW, Bonekat WH, et al. Relation of sleepiness to respiratory disturbance index: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:502–507. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.2.9804051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young T, Finn L. Epidemiological insights into the public health burden of sleep disordered breathing: sex differences in survival among sleep clinic patients. Thorax. 1998;53(Suppl. 3):S16–S19. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.2008.s16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ancoli-Israel S, Klauber MR, Stepnowsky C, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in African-American elderly. J Gerontol. 1989;44:M18–M21. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiestand DM, Britz P, Goldman M, et al. Prevalence of symptoms and risk of sleep apnea in the US population: results from the national sleep foundation sleep in America 2005 poll Estimation of the clinically diagnosed proportion of sleep apnea syndrome in middle-aged men and women. Chest. 2006;130:780–786. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.3.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Redline S, Tishler PV, Hans MG, et al. Racial differences in sleep-disordered breathing in African-Americans and Caucasians. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:186–192. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colten HR, Altevogt BM. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2006. Functional and economic impact of sleep loss and sleep-related disorders. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman M, Bliznikas D, Klein M, et al. Comparison of the incidences of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome in African-Americans versus Caucasian-Americans. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:545–550. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Connor GT, Lind BK, Lee ET, et al. Variation in symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing with race and ethnicity: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep. 2003;26:74–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jean-Louis G, Zizi F, von Gizycki H, et al. Evaluation of Sleep Apnea in a Sample of Black Patients. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;15:421–425. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, et al. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation. 2005;111:1233–1241. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158136.76824.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phillipson EA. Sleep apnea – a major public health problem. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1271–1273. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Sleep Foundation. Washington, DC: National Sleep Foundation; 2005. Sleep in America poll; pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in the physician workforce. Facts and figures 2008. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Association of American Medical Colleges. Minorities in medical education. Facts and figures 2005. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenks C, Phillips M. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press; 1998. The Black-White test score gap: an introduction, the American Prospect. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Committee for the Assessment of NIH Minority Research Training Programs, Oversight Committee for the Assessment of NIH Minority Research Training Programs, Board on Higher Education and Workforce Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005. Assessment of NIH minority research and training programs: phase 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ginther DK, Schaffer WT, Schnell J, et al. Race, ethnicity, and NIH research awards. Science. 2011;333:1015–1019. doi: 10.1126/science.1196783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Program to increase diversity among individuals engaged in health-related research (PRIDE) [accessed 07.11.14]; < http://www.med.nyu.edu/pophealth/divisions/chbc/pride>. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kram KE. Mentoring in the Workplace. In: Katzell RA, editor. Career development in organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1986. pp. 160–201. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boice R. Lessons learned about mentoring. In: Sorcinelli MD, Austin AE, editors. Developing new and junior faculty. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1991. pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewellen-Williams C, Johnson VA, Deloney LA, et al. The POD: a new model for mentoring underrepresented minority faculty. Acad Med. 2006;81:275–279. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200603000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feldman MD, Arean PA, Marshall SJ, et al. Does mentoring matter: results from a survey of faculty mentees at a large health sciences university. Med Educ Online. 2010;15:5063. doi: 10.3402/meo.v15i0.5063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas DA. The truth about mentoring minorities. Race matters. Harv Bus Rev. 2001;79:98–107. 168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Treisman U. Studying students studying calculus: a look a the lives of minority mathematics students in college. Coll Math J. 1992;23:362–372. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russell SH, Hancock MP, McCullough J. The pipeline. Benefits of undergraduate research experiences. Science. 2007;316:548–549. doi: 10.1126/science.1140384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schultz PW, Hernandez P, Woodcock A, et al. Patching the pipeline: reducing educational disparities in the sciences through minority training programs. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 2011;33:114. doi: 10.3102/0162373710392371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol. 1982;37:122–147. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cullen DL, Rodak B, Fitzgerald N, et al. Minority students benefit from mentoring programs. Radiol Technol. 1993;64:226–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clance P, Imes S. The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: dynamics and therapeutic intervention. psychotherapy theory. Psychotherapy (Chic) 1978;15:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmader T, Johns M, Forbes C. An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance. Psychol Rev. 2008;115:336–356. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steele CM. A threat in the air. How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. Am Psychol. 1997;52:613–629. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franco I, Bailey L, Bakos A, et al. The Continuing Umbrella of Research Experiences (CURE): a model for training underserved scientists in cancer research. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26:92–96. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0126-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehrotra C, Townsend A, Berkman B. Enhancing research capacity in gerontological social work. Educ Gerontol. 2009;35:146–163. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mehrotra C. Follow-up evaluation of a faculty training program in aging reserach. Educ Gerontol. 2006;32:493–503. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2014.852930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ishihara K, Miyashita A, Inugami M, et al. The results of investigation by the Japanese version of Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire. Shinrigaku Kenkyu. 1986;57:87–91. doi: 10.4992/jjpsy.57.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillip JJ. Handbook of training evaluation and measurement methods. Houston, TX: Gulf; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gustafson K, Branch R. Revisioning models of instructional development. Educ Technol Res Dev. 2010;45:73–89. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson GF, Switzer GE, Cohen ED, et al. A shortened version of the clinical research appraisal inventory: CRAI-12. Acad Med. 2013;88:1340–1345. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829e75e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dilmore TC, Rubio DM, Cohen E, et al. Psychometric properties of the mentor role instrument when used in an academic medicine setting. Clin Transl Sci. 2010;3:104–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2010.00196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]