Abstract

Introduction

Ultrasound is usually the first diagnostic investigation for the assessment of liver lesions. Apart from conventional sonography (CS), new grey-scale sonographic techniques have been developed which have increased the application of ultrasound in liver imaging. The present study was undertaken to compare image quality of CS, real-time compound sonography (RTCS), tissue harmonic sonography (THS) and tissue harmonic compound sonography (THCS) in focal liver lesions.

Materials and methods

100 patients with focal hepatic lesions were enroled. Lesions were divided into solid and cystic group. Solid lesions were evaluated for lesion conspicuity and elimination of artefacts. For cystic lesions, lesion conspicuity, posterior acoustic enhancement and internal echoes within the lesion were evaluated. Grading was done using 3–5-point scales. Overall image quality was assessed depending on the total points.

Results

78 solid and 22 cystic liver lesions were included. THCS showed superior results for lesion conspicuity, elimination of artefacts and overall image quality in solid lesions. RTCS showed similar results as THCS for lesion conspicuity and overall image quality in solid lesions. THS gave better results in cystic lesions for all imaging parameters. Results of THCS though slightly inferior, showed no significant difference from THS, in cystic lesions. CS was found to have least diagnostic value in characterisation.

Conclusions

For evaluation of focal hepatic lesions, a combination of compound and harmonic sonography, i.e. THCS, is the preferred sonographic technique.

Keywords: Ultrasonography, Liver, Liver lesions, Tissue harmonic imaging, Compound US

Riassunto

Introduzione

l’ecografia è di solito l’indagine radiologica iniziale, non invasiva e semplice, per la valutazione delle lesioni epatiche. Oltre alla tradizionale ecografia in scala di grigi (CS), sono state sviluppate delle nuove tecniche, che hanno aumentato le applicazioni dell’ecografia nell’imaging del fegato. Il presente studio è stato intrapreso per confrontare la qualità delle immagini in: CS, ecografia in tempo reale con compound (RTCS), armonica tissutale (THS) e armonica tissutale con compound (THC) nello studio delle lesioni focali epatiche.

Materiali e Metodi

sono stati arruolati 100 pazienti con lesioni focali epatiche. Le lesioni sono state divise in solide e cistiche. Per le lesioni solide sono stati valutati la visibilità e l’eliminazione di artefatti. Per le lesioni cistica sono stati valutati la visibilità, il rinforzo acustico posteriore e gli echi all’interno delle lesioni. La classificazione è stata effettuata utilizzando una scala da 3 a 5. La qualità generale dell’immagine è stata valutata in base al totale dei punti.

Risultati

sono state incluse 78 lesioni epatiche solide e 22 cistiche. La THC ha mostrato risultati superiori per la visibilità delle lesioni, l’eliminazione di artefatti e la qualità complessiva dell’immagine delle lesioni solide. La RTCS ha mostrato risultati simili a quelli di THC per la visibilità delle lesioni e la qualità complessiva dell’immagine delle lesioni solide. THS ha dato risultati migliori per tutti i parametri di imaging delle lesioni cistiche. I risultati della THC, anche se leggermente inferiori, non hanno mostrato differenze significativa dalla THS, nelle lesioni cistiche. E’ stato valutato che la CS abbia un valore diagnostica minore nella caratterizzazione.

Conclusioni

per la valutazione delle lesioni focali epatiche, una combinazione di compound ed armonica tissutale (THC) è la tecnica ecografica da preferire.

Introduction

Focal liver lesions are frequently detected during ultrasound (US) examination due to its cost effective, availability and lack of radiation hazard. It is very cost effective and is a widely available modality with no associated radiation hazards. Apart from conventional sonography (CS), new grey-scale sonographic techniques have been developed which have increased the application of ultrasound in liver imaging.

Conventional sonography (CS) uses the same frequency bandwidth for both the transmitted signals and the received signals. The target tissue in CS is examined only from a single viewing angle. Therefore, images are degraded by the presence of many artefacts, including speckle, clutter and refraction [1].

In real-time compound sonography (RTCS), the target tissue is imaged from different angles and these multiple overlapping images are then averaged to form one compound image [1, 2]. Since the lesion is viewed from multiple angles, signals from the true structure are added up, while artifactual echoes are not. The result is a better, more realistic image, with reduced artefacts (such as speckle), better image contrast and improved signal to noise ratio [1–4]. In recent years, its multiangled property has been shown to improve the image quality in the sonography of breast, vessels, thyroid, musculoskeletal system and abdomino-pelvic organs [4–9].

Tissue harmonic sonography (THS) provides better image quality than CS and is based on the phenomenon of non-linear distortion of acoustic signals as they travel through tissues [1, 10–12]. Harmonics are multiples of fundamental or transmitted frequency. Higher harmonic frequencies are generated by the propagation of ultrasonic waves through tissues. A band-pass filter is used to process the received signal. The image obtained by THS is better due to reduced artefacts, improved signal to noise ratio, enhanced contrast and better spatial resolution [10–16]. The improved image quality of THS has led to its widespread use in evaluation of the abdomen (liver, kidney, gall bladder, bile ducts), vessels and breasts [7–9, 17–27]. Limitations of THS include overall coarse echo texture and decreased penetration [17, 18].

With advanced technology, RTCS can now be combined with THS [7–9]. In this technique, i.e. tissue harmonic compound sonography (THCS), both sonographic modalities act synergistically. Thus, the advantages of both of these techniques can be combined while overcoming their limitations, providing an improved image of the target tissue.

The present prospective study was conducted to compare the different sonographic technologies for characterisation of hepatic lesions.

Materials and methods

Patient enrolment

The study was approved by our institute’s review board. A total of 100 consecutive patients with focal liver lesions were enroled in this study. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. All of the patients provided written informed consent for enrolment in the study and for the inclusion of information in this article that could potentially lead to their identification.

The main indications for ultrasound included abdominal pain (35 %), abdominal lump (17 %), weight loss (10 %), jaundice (8 %) and fever (6 %). In 19 % of the patients, liver lesions were detected either incidentally during screening of cirrhotic patients or during evaluation for extra-hepatic pathologies.

Patient selection and image acquisition were done prospectively, and then the images were independently analysed by two radiologists.

Image acquisition

Sonographic examination of the focal liver lesions was performed on PHILIPS HD11 (high definition) ultrasonic system (ATL International, LLC, Bothell, WA 980413003, USA), using a 2–5 MHz curvilinear transducer. After initial evaluation of the entire liver, a detailed examination was carried out for the focal liver lesions. If liver had multiple lesions, the largest hepatic lesion was analysed. For each liver lesion, CS was performed first, followed by RTCS, THS and finally THCS. During scanning, the plane of the scan was kept as constant as possible. Various imaging parameters, including focus, depth and magnification were optimised during CS, and those identical parameters were also used when scanning with the other modes. However, image gain was adjusted for each image. For RTCS, survey mode was used in which the compound image is constructed from combination of three to five coplanar images that are acquired from successive and different viewing angles. For THS, a conventional technique using band-pass filter was used. A complete set of four images was obtained for each focal lesion in the liver. All of the images were stored in a computer file. The annotations were removed and numerical coding was assigned. These images were arranged randomly before the image analysis was conducted.

Image analysis

Two experienced radiologists having more than 10 years of expertise in ultrasound (blinded to the imaging technique used), independently compared the random images of all of the focal liver lesions. During the image analysis, the liver lesions were primarily described as solid or cystic.

Solid lesions were evaluated for lesion conspicuity and the presence of unwanted artefacts. Cystic lesions were evaluated for lesion conspicuity, posterior acoustic enhancement and internal echoes within the lesion. Grading for these imaging parameters was done using 3- to 5-point scales. Finally, overall image quality was assessed for both the solid and cystic liver lesions.

Lesion conspicuity was rated on the basis of margin clarity as follows: 4 for well defined, 3 for partially obscured, 2 for moderately obscured and 1 for ill-defined. Elimination of unwanted artefacts was graded as follows: 3 for no artefacts, 2 for single artefact and 1 for two or more than two artefacts. Posterior acoustic enhancement was graded as follows: 5 for cystic lesions with white posterior acoustic enhancement with good demarcation, 4 for grey with good demarcation, 3 for grey with vague demarcation, 2 for faint and 1 for the absence of posterior acoustic enhancement.

Internal echoes within the cystic lesion were graded as follows: 4 for black lumen with no internal echoes, 3 for mild echoes in less than one-third of the cyst, 2 for moderate internal echoes between one-third and two-thirds of the cyst and 1 for internal echoes covering more than two-thirds of the cyst. Overall image quality was assessed objectively based on the total points assigned to each lesion and it was graded as good (6–7 for solid and 10–13 for cystic lesions), fair (4–5 for solid and 6–9 for cystic lesions) and poor (2–3 for solid and 3–5 for cystic lesions).

Statistical comparison of the four sonographic techniques was done using Friedman’s and Wilcoxon’s signed rank tests, based on the results of observations by two radiologists.

Results

Of the 100 patients, 46 were males and 54 were females. The mean age was 47 years (range 8–84 years).

Of the 100 liver lesions, there were 78 solid lesions and 22 cystic lesions. These included metastases (n = 42), simple cysts (n = 15), hemangiomas (n = 12), hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC, n = 8), liver abscesses (n = 7), hydatid cysts (n = 5), lymphoma (n = 5), indeterminate lesions (n = 3), hepatic adenomas (n = 2) and hepatic angiomyolipoma (n = 1). The mean size of the hepatic lesion was 4.4 cm (range 1–14.1 cm).

The values of κ score for the elimination of artefacts (THCS) and overall image quality (RTCS and THS) showed moderate agreement (κ score > 0.4) between the two radiologists. The values of kappa score for the lesion conspicuity (CS, RTCS, THS, THCS), elimination of artefacts (CS, RTCS, THS), internal echoes within the lesion (CS, RTCS, THS, THCS) and overall image quality (CS, THCS) indicated fair agreement (κ value < 0.4) between the two radiologists. The mean scores of points given by the two observers for each imaging parameter using four different sonographic techniques are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean scores of various imaging parameters using four different techniques in 100 focal liver lesions

| Imaging parameter | Imaging modality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | RTCS | THS | THCS | ||

| Lesion conspicuity | Solid | 2.84 (2.74–2.93) | 3.54 (3.47–3.61) | 2.86 (2.76–2.96) | 3.58 (3.52–3.65) |

| Cystic | 3.31 (3.17–3.45) | 3.47 (3.35–3.60) | 3.92 (3.86–3.98) | 3.86 (3.79–3.94) | |

| Elimination of artefacts | 2.79 (2.73–2.84) | 2.90 (2.86–2.93) | 2.95 (2.93–2.98) | 2.97 (2.95–2.99) | |

| Posterior acoustic enhancement | 3.2 (3.01–3.4) | 3.33 (3.13–3.53) | 4.52 (4.36–4.69) | 4.27 (4.08–4.46) | |

| Internal echoes within lesion | 1.41 (1.22–1.32) | 1.58 (1.40–1.76) | 3.22 (3–3.43) | 3.08 (2.87–3.29) | |

| Overall image quality | Solid | 5.63 (5.51–5.74) | 6.44 (6.36–6.51) | 5.98 (5.88–6.08) | 6.55 (6.49–6.62) |

| Cystic | 7.9 (7.56–8.23) | 8.35 (8.0–8.7) | 11.51 (11.17–11.85) | 11.19 (10.85–11.54) | |

CS conventional sonography, RTCS real-time compound sonography, THS tissue harmonic sonography, THCS tissue harmonic compound sonography

Table 2 provides statistical comparison of all four imaging techniques based on the results of the observations of two radiologists for each parameter.

Table 2.

Comparison between the four techniques for each imaging parameter

| Imaging parameter | Imaging quality (P < 0.05) |

|---|---|

| Lesion conspicuity | Solid lesions: THCS = RTCS > THS = CS Cystic lesions: THS = THCS > RTCS > CS |

| Elimination of artefacts | THCS = THS, THCS > RTCS, THS = RTCS, RTCS > CS |

| Posterior acoustic enhancement | THS = THCS > RTCS = CS |

| Internal echoes within lesion | THS = THCS > RTCS = CS |

| Overall image quality | THCS > RTCS = THS > CS Solid lesions: THCS = RTCS > THS > CS Cystic lesions: THS = THCS > RTCS > CS |

THCS tissue harmonic compound sonography, RTCS real-time compound sonography, THS tissue harmonic sonography, CS conventional sonography

Lesion conspicuity (LC)

For the lesion conspicuity (LC) in the focal liver lesions, the order of the mean scores was THCS first, followed by RTCS, THS and then CS. In the solid lesions, compound imaging (RTCS alone or in combination with THS, i.e. THCS) was significantly better than the other techniques (P < 0.05), while in the cystic lesions, harmonic imaging (THS alone or in combination with RTCS, i.e. THCS) showed much better results (Figs. 1, 2).

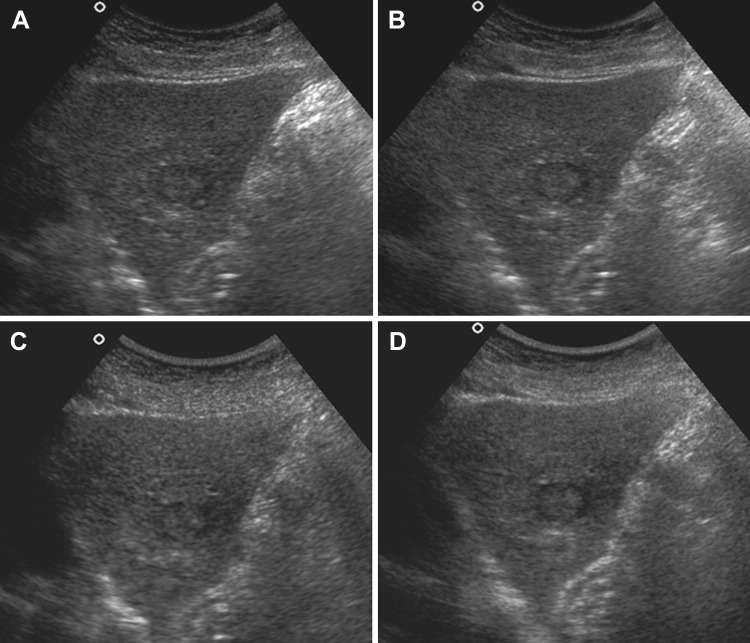

Fig. 1.

Lesion conspicuity of solid lesion in 45-year-old male with metastasis showing isoechoic lesion in segment II with hypoechoic rim. a CS image shows moderately obscured margins. Faint ill-defined peripheral hypoechoic halo is also seen (LC score = 2). b RTCS image shows well-defined margins. Peripheral halo is better appreciated (LC score = 4). c THS image showing partially obscured margins with ill-defined peripheral hypoechoic halo (LC score = 3). d THCS image shows well-defined margins of the lesion with well appreciated thin peripheral halo around it (LC score = 4)

Fig. 2.

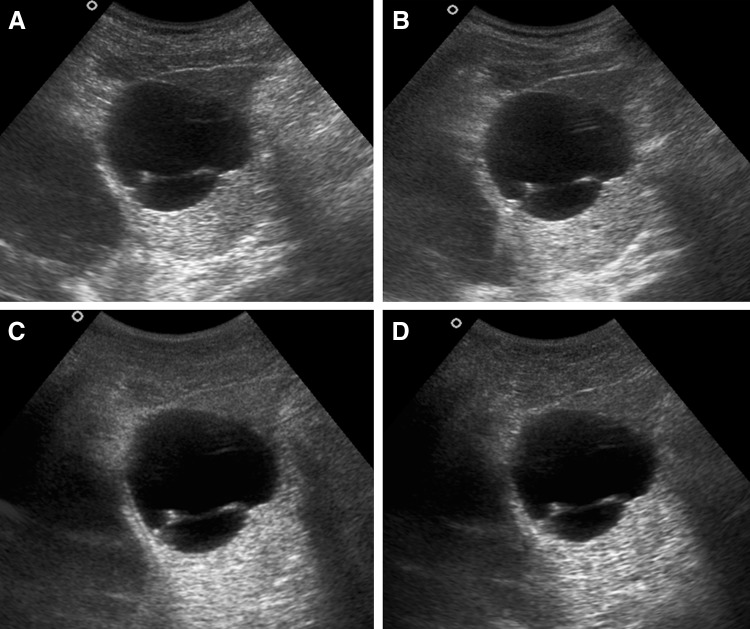

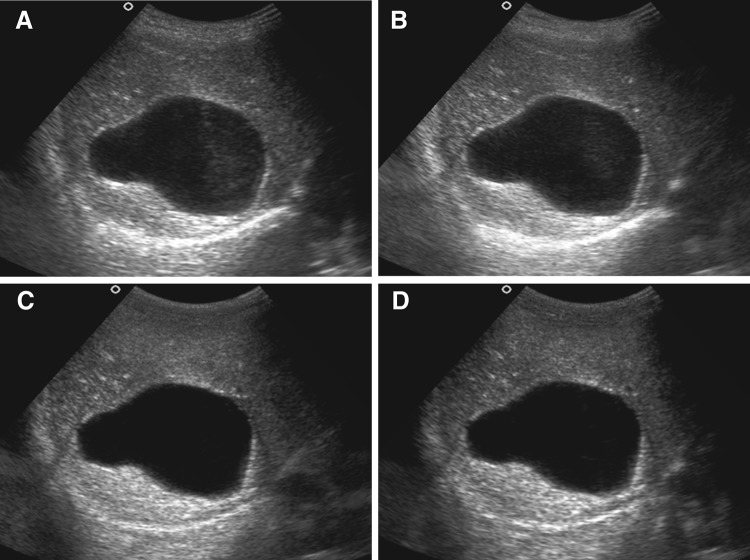

Posterior acoustic enhancement (PAE) in cystic liver lesion in a 29-year-old male patient with hepatic cyst in segment II of liver. a CS image shows grey PAE behind the lesion with vague demarcation (PAE score = 3). b RTCS image shows presence of grey PAE with sharp demarcation (PAE score = 4). c THS image shows white PAE with sharp demarcation behind the cystic hepatic lesion (PAE score = 5). d THCS image also shows white PAE with sharp demarcation behind the cystic hepatic lesion (PAE score = 5)

Elimination of unwanted artefacts

The order of the mean scores for artefact elimination was THCS first, followed by THS, RTCS and then CS (Fig. 3). THCS and THS alone did not show a significant difference (P < 0.05) in their values. THCS was, however, significantly better than RTCS alone and CS. No significant statistical difference was seen between THS and RTCS for artefact elimination. RTCS alone was better than the CS, which was least useful.

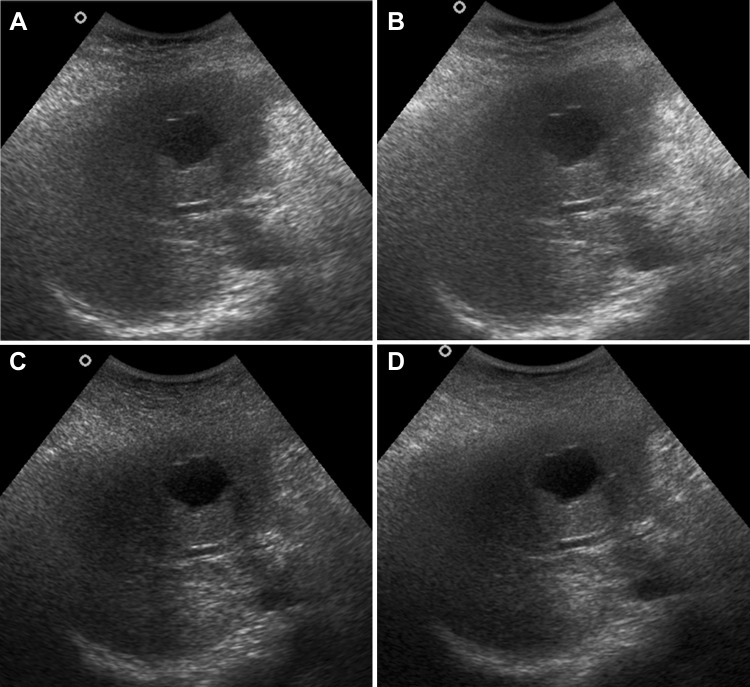

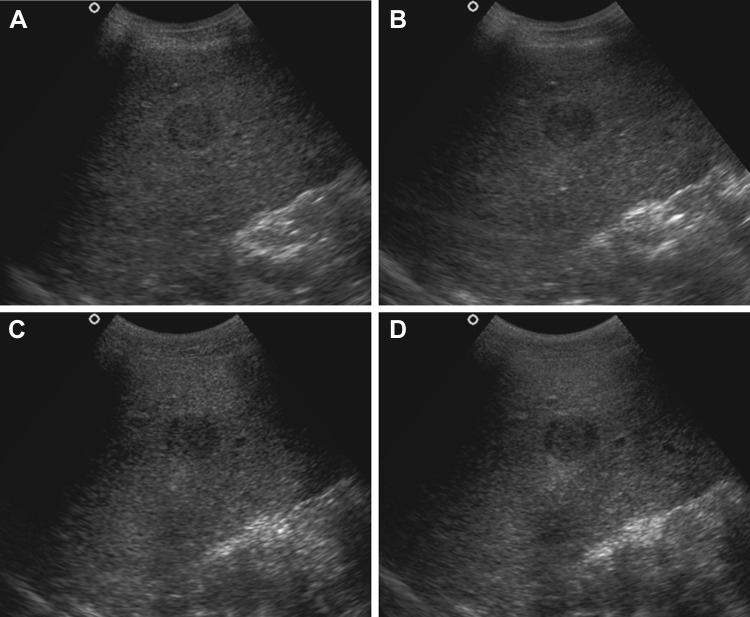

Fig. 3.

Internal echoes within cystic liver lesion in a 8-year-old female child with simple hepatic cyst in segment VI of liver. a CS image shows presence of internal echoes in more than 2/3rd of this cystic lesion (IE score = 1). b RTCS image also shows presence of internal echoes in more than 2/3rd of this cystic lesion (IE score = 1). c Corresponding THS image shows no internal echoes within the lesion (IE score = 4). d THCS image shows internal echoes confined to less than 1/3rd of the lesion (IE score = 3)

Posterior acoustic enhancement (PAE)

In terms of the average scores for PAE, THS showed superior results, followed by THCS, RTCS and then CS (Fig. 4). Thus at P < 0.05, harmonic imaging was better than the other techniques for PAE. In harmonic imaging, no statistically significant difference was seen in the values of THS and THCS; however, THS alone showed slightly better results than THCS. RTCS alone and CS did not reveal any significant difference in their values.

Fig. 4.

Posterior acoustic enhancement (PAE) in cystic liver lesion in a 29-year-old male patient with hepatic cyst in segment II of liver. a CS image shows grey PAE behind the lesion with vague demarcation (PAE score = 3). b RTCS image shows presence of grey PAE with sharp demarcation (PAE score = 4). c THS image shows white PAE with sharp demarcation behind the cystic hepatic lesion (PAE score = 5). d THCS image also shows white PAE with sharp demarcation behind the cystic hepatic lesion (PAE score = 5)

Internal echoes within lesion (IE)

The order of the mean values for elimination of internal echoes was THS first, followed by THCS, RTCS and then CS (Fig. 5). Harmonic imaging was significantly superior to RTCS and CS (P < 0.05), with THS alone showing slightly better values than the THCS. No statistically significant difference was seen between RTCS and CS.

Fig. 5.

Internal echoes within cystic liver lesion in 8-year-old female child with simple hepatic cyst in segment VI of liver. a CS image shows presence of internal echoes in more than 2/3rd of this cystic lesion (IE score = 1). b RTCS image also shows presence of internal echoes in more than 2/3rd of this cystic lesion (IE score = 1). c Corresponding THS image shows no internal echoes within the lesion (IE score = 4). d THCS image shows internal echoes confined to less than 1/3rd of the lesion (IE score = 3)

Overall image quality (OIQ)

For the 100 focal liver lesions, order for OIQ in focal lesions of liver was THCS > RTCS = THS > CS, at a P value of <0.05. Thus, THCS was best for the overall evaluation of focal hepatic lesions, showing significantly better values than the other three imaging modalities.

For the solid lesions, compound imaging, i.e. THCS and RTCS, was significantly better than the other modalities. THCS showed slightly, but not significantly superior results than the RTCS alone. THS alone was better than CS, which was the least useful of all the imaging techniques.

For the cystic lesions, THS and THCS showed significantly better results than the other techniques. THS, however, showed slightly, but not significantly superior results than THCS. This was followed by the RTCS. CS was least useful for assessment of OIQ in the cystic lesions.

Discussion

Sonography is a well recognised first imaging technique for the evaluation of patients with suspected abdominal pathologies, as it is an easily available, non-invasive and very cost-effective imaging modality with a lack of radiation exposure. Focal liver lesions are the most common abnormalities detected while performing an abdominal US. They are seen as discrete abnormalities arising within the liver, against the background of relatively normal liver parenchyma. Apart from CS, new grey-scale sonographic techniques have been developed, which have increased the application of ultrasound in liver imaging. These include compound and harmonic sonographic techniques.

In our study, THCS proved to be the best technique for clearer depiction of the margins of lesion when compared to the other three techniques. It had the advantages of THS as well as the multiangled scanning property of RTCS, thus improving lesion conspicuity. In RTCS, the continuity of specular reflectors provided better delineation of walls, thus improving lesion conspicuity. This improvement in LC with THCS and RTCS was better appreciated in solid liver lesions when compared to cystic lesions. THCS, however, showed slightly better results than RTCS alone. For solid lesions, THS was found to be inferior to THCS and RTCS, probably due to coarse echo texture, reduced axial resolution in THS, and the multiangled isonation used in both RTCS and THCS. CS was the least useful of all four modalities for LC in our study.

Kim et al. and Yen et al. have shown THCS to be best technique for lesion conspicuity of cystic liver lesions [8, 9]. In our study also, for cystic lesions, both THS and THCS were equally better for LC than RTCS alone and CS.

The elimination of unwanted artefacts was greatest with the use of THCS in our study. This can be attributed to the inherent multiangle scanning of RTCS and strong harmonic signals obtained from true structures with THS. There was significant reduction of speckle, clutter, reverberation and refraction artefacts in THCS. Multiangled scanning of RTCS also showed significant reduction of many unwanted artefacts especially speckle.

Speckle results from the interference of acoustic fields generated by the scattering of sound beams from tissue reflectors, giving a grainy appearance to the image [28]. This random phenomenon is reduced with the use of RTCS. When compared to CS, THS alone also showed better reduction in unwanted artefacts. In our study, no significant difference was found between RTCS and THS. Oktar et al. and Yen et al., however, found RTCS to be better than THS for the elimination of artefacts in abdomino-pelvic and hepatic lesions [7–9]. However, a few hepatic lesions showed the presence of edge shadowing, as was seen in comparative images obtained with the use of THS. This artefact was mildly reduced when compared to THS due to multiangled scanning using RTCS alone.

We also encountered few refraction artefacts, especially edge shadowing in some of the focal liver lesions with THS. Edge shadowing is produced when sound waves strike the curved peripheral surface of the liver lesion at a critical angle [28]. This artefact was, however, reduced in corresponding images obtained with RTCS and THCS, probably due to inherent multiangle scanning [6].

Acoustic sonographic features like posterior acoustic enhancement and posterior acoustic shadowing are accentuated with the use of THS, probably due to the higher receiving frequency and narrow dynamic range used in this technique. Likewise, in our study, THS provided the best delineation of posterior acoustic enhancement. THCS also provides better demonstration of posterior acoustic enhancement, due to its inherent harmonic component. But the results of THCS were slightly, though not significantly, inferior to THS alone. This can be attributed to the added component of compound scanning (i.e. RTCS) in THCS. THCS was, however, better than RTCS alone and CS for posterior acoustic enhancement. In RTCS, the peripheries of lesions showed diminished posterior acoustic enhancement due to non-overlapping of steered images in peripheral portions, while central portions just behind the lesions showed intense posterior enhancement in a triangular fashion due to maximum overlapping in this region. For posterior acoustic shadowing, similar results have been described with use of RTCS. However, this is sometimes found to be useful in few cases, as tissue behind the cystic lesion can be better visualised, due to a reduction in posterior enhancement and shadowing, without manipulation of the transducer.

Demonstration of internal echoes within cystic lesions was also better with the use of THS and THCS (with THS alone showing slightly superior results). This is attributed to the absence of generation of harmonic signals from the central anechoic component of cysts while in CS and RTCS; there is artefactual echo generation from the clear content of simple cystic lesions. However, Kim et al. showed no significant difference between THS and RTCS for the demonstration of internal echoes in cystic lesion [8].

In this study, overall image quality with THCS was found to be best for focal liver lesions, due to the added advantages of THS and RTCS with reduced artefacts. Our results confirmed the theoretical advantages of combining THS and RTCS. When solid and cystic lesions were evaluated separately, THCS was again found to be best for solid liver lesions. But, for cystic hepatic lesions, THS alone and THCS both were found to be significantly better than RTCS and CS. CS was found to be least useful for overall image quality for both solid and cystic liver lesions.

There were few limitations in our study. As a single radiologist had imaged the liver lesions using all four techniques, there could have been bias during image collection. Though two observers were unaware of the imaging modalities used, absolute blinding was very difficult, as there was significant difference in the qualities of CS, RTCS, and THS. As image analysis was done by two radiologists only, their results could have reflected subjective bias, as some radiologists tend to prefer smoother image of RTCS, while others prefer a coarser image provided by harmonic US. Lastly, the sample size of cystic lesions was small.

To conclude, tissue harmonic compound sonography provides best lesion conspicuity, the elimination of artefacts, posterior acoustic enhancement, the demonstration of internal echoes, and the best overall image quality in focal liver lesions.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

UR: No conflict of interest, NKa: No conflict of interest, AKS: No conflict of interest, AB: No conflict of interest, MSS: No conflict of interest, AKD: No conflict of interest, YKC: No conflict of interest, NK: No conflict of interest.

Informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. All patients provided written informed consent to enrolment in the study and to the inclusion in this article of information that could potentially lead to their identification.

Human and animal studies

The study was conducted in accordance with all institutional and national guidelines. The study described in this article does not contain studies with animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Merritt CRB. Updates in ultrasonography. Radiol Clin North Am. 2001;39:1–10. doi: 10.1016/S0033-8389(05)70287-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Claudon M, Tranquart F, Evans DH, Lefevre F, Correas JM. Advances in ultrasound. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:7–18. doi: 10.1007/s00330-001-1185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim KW, Choi BI, Yoo SY, Kim YH, Kim H-C, Lee HJ, et al. Real time compound ultrasonography: pictorial review of technology and the preliminary experience in clinical application of the abdomen. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29:491–497. doi: 10.1007/s00261-003-0158-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Entrekin RR, Porter BA, Silesen HH, Wong AD, Cooperberg PL, Fix CH. Real-time spatial compound imaging: application to breast, vascular, and musculoskeletal ultrasound. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2001;22:50–64. doi: 10.1016/S0887-2171(01)90018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin DC, Nazarian LN, O’Kane PL, McShane JM, Parker L, Meritt CRB. Advantages of real-time spatial compound sonography of the musculoskeletal system versus conventional sonography. Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1629–1631. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.6.1791629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shapiro RS, Simpson WL, Rausch DL, Yeh HC. Compound spatial sonography of the thyroid gland: evaluation of freedom from artifacts and of nodule conspicuity. Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:1195–1198. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.5.1771195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oktar SO, Yucel C, Ozdemir H, Uluturk A, Isik S. Comparison of conventional sonography, real-time compound sonography, tissue harmonic sonography, and tissue harmonic compound sonography of abdominal and pelvic lesions. Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1341–1347. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.5.1811341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SH, Lee JM, Kim KG, Kim JH, Han JK, Lee JY, et al. Comparison of fundamental sonography, tissue-harmonic sonography, fundamental compound sonography, and tissue-harmonic compound sonography for focal hepatic lesions. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:2444–2453. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yen CL, Jeng CM, Yang SS. The benefits of comparing conventional sonography, real-time spatial compound sonography, tissue harmonic sonography, and tissue harmonic compound sonography of hepatic lesions. Clin Imaging. 2008;32:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandhu MS (2007) Tissue harmonic imaging. In: Berry M, Chowdhury V, Suri S, Mukhopadhyay S (eds) Advances in imaging technology, 2nd edn. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd, N Delhi, pp 12–18

- 11.Dresser TS, Jeffery RB. Tissue harmonic imaging techniques: physical principles and clinical applications. Semin Ultrasound CT MRI. 2001;22:1–10. doi: 10.1016/S0887-2171(01)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whittingham TA. Tissue harmonic imaging. Eur Radiol. 1999;9:S323–S326. doi: 10.1007/PL00014065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenthal SJ, Jones PH, Wetzel LH. Phase inversion tissue harmonic sonographic imaging: a clinical utility study. Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:1393–1398. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.6.1761393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lencioni B, Coini D, Bartolozzi C. Tissue harmonic and contrast specific imaging: back to gray scale in ultrasound. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:151–165. doi: 10.1007/s003300101022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shapiro RS, Wagriech J, Parsons RB, Stancato-Pasik A, Yeh HC, Lao R. Tissue harmonic imaging sonography: evaluation of image quality compared with conventional sonography. Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1203–1206. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.5.9798848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sodhi KS, Sidhu R, Gulati M, Saxena A, Suri S, Chawla Y. Role of tissue harmonic imaging in focal hepatic lesions: comparison with conventional sonography. J Gastroentrol Hepatol. 2005;20:1488–1493. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yucel C, Ozdemir H, Asik E, Isik S. Benefits of tissue harmonic imaging in evaluation of abdominal pelvic lesions. Abdom Imaging. 2003;28:103–109. doi: 10.1007/s00261-001-0157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jang HJ, Lim HK, Lee WJ, Kim SH, Kim KA, Kim EY. Ultrasonographic evaluation of focal hepatic lesions: comparison of pulse inversion harmonic, tissue harmonic, and conventional imaging techniques. J Ultrasound Med. 2000;19:293–299. doi: 10.7863/ultra.19.5.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt T, Hohl C, Haage P, Blaum M, Honnef D, Weib C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of phase-inversion tissue harmonic imaging versus fundamental B-mode sonography in the evaluation of focal lesions of the kidney. Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:1639–1647. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.6.1801639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szopinski KT, Pajk AM, Wysocki M, Amy D, Szopinska M, Jakubowski W. Tissue harmonic imaging; utility in breast sonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:479–487. doi: 10.7863/jum.2003.22.5.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hann LE, Bach AM, Cramer LD, Siegel D, Yoo HK, Garcia R. Hepatic sonography: comparison of tissue harmonic and standard sonography techniques. Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:201–206. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.1.10397127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka S, Oshikawa O, Sasaki T, Ioka T, Tsukuma H. Evaluation of tissue harmonic imaging for diagnosis of focal liver lesions. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2000;26:183–187. doi: 10.1016/S0301-5629(99)00134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kubota K, Hisa N, Nishikawa T, Ohnishi T, Ogawa Y, Yoshida S. The utility of tissue harmonic imaging in liver: a comparison with the conventional gray-scale sonography. Oncol Rep. 2000;7:767–771. doi: 10.3892/or.7.4.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaudhry S, Gorman B, Charboneau JW, Tradup DJ, Beck RJ, Kofler JM, et al. Comparison of tissue harmonic imaging with conventional US in abdominal disease. Radiographics. 2000;20:1127–1135. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.4.g00jl371127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong HS, Han JK, Kim TK, Kim YH, Kim JS, Cha JH, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the gall bladder: comparison of fundamental, tissue harmonic and pulse inversion harmonic imaging. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20:35–41. doi: 10.7863/jum.2001.20.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ortega D, Burns P, Simpson DH, Wilson SR. Tissue harmonic imaging: is it a benefit for bile duct sonography? Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:653–659. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.3.1760653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mesurolle B, Bining HJS, Khoury ME, Barhdadi A, Kao E. Contribution of tissue harmonic imaging and frequency compound imaging in interventional breast sonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:845–855. doi: 10.7863/jum.2006.25.7.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scanlan KA. Sonographic artifacts and their origin. Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:1267–1272. doi: 10.2214/ajr.156.6.2028876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]