Abstract

Data from real-world studies of ranibizumab in neovascular (wet) age-related macular degeneration suggest that outcomes in clinical practice fail to match those seen in clinical trials. These real-world studies follow treatment regimens that differ from the fixed dosing used in the pivotal clinical trial programme. To better understand the effectiveness of ranibizumab in clinical practice, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of 12-month outcomes reported in peer-reviewed ‘real-world' publications. Key measures included in our analysis were mean change in visual acuity (VA) and the proportion of patients gaining ≥15 letters or losing ≤15 letters. Twenty studies were eligible for inclusion in our study, with 18 358 eyes having sufficient data for analysis of 12-month outcomes. Mean baseline VA ranged from 48.8 to 61.6 Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study letters. Mean change in VA was between −2.0 and +5.5 letters, with a grand mean of +2.9±3.2, and a weighted mean (adjusted for the number of eyes in the study) of +1.95. Eleven studies reported that 19±7.5 (mean value) of patients gained ≥15 letters, while in 12 studies the mean percentage of patient losing ≤15 letters was 89±6.5%. Our comprehensive analysis of real-world ranibizumab study data confirm that patient outcomes are considerably poorer than those reported in randomised control trials of both fixed and pro re nata regimens.

Introduction

Wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a chronic, progressive disease of the central retina and a major cause of irreversible vision loss worldwide.1, 2 Central to the pathogenesis of the disease is the overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which stimulates choroidal neovascularization and causes blood and fluid to leak into the macula. The last decade has seen the introduction of intravitreal anti-VEGF agents, which have revolutionized the treatment of wet AMD, offering patients previously unachievable improvements in vision.

Ranibizumab (Lucentis), a humanised monoclonal antibody fragment, was the first anti-VEGF agent shown to improve visual acuity (VA) in patients with wet AMD.3, 4, 5 Regulatory approval for the use of ranibizumab was granted on the basis of the MARINA4, 6, 7 and ANCHOR3, 8 study data, which showed mean gains of 7–11 letters over 12 months with monthly dosing. Up to 40% of patients gained more than 15 letters during this time and few lost vision. Moreover, improvements were largely maintained at the 24-month follow-up.

The early clinical trial data clearly demonstrated the benefits that ranibizumab could offer; however, the requirement for monthly intravitreal injections places a high burden on patients and healthcare systems. Subsequent studies, therefore, investigated whether equivalent VA gains could be achieved with less frequent injections. In the PIER study, patients received three monthly loading doses followed by quarterly injections of 0.5 mg ranibizumab.9 However, there was a mean loss of 0.2 letters by month 12. Other studies used pro re nata (PRN) regimens, where the decision to administer the drug is dependent on the disease status assessed by the physician at regular monitoring visits (eg, vision worsening or increase in macula thickness). Outcomes of these PRN regimens are variable with mean gains of 2.3–9.3 letters.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 For example, in the SAILOR study, which utilised a PRN regimen based around quarterly monitoring visits following three initial monthly doses, there was a mean gain of only 2.3 letters.10 By contrast, the results from the PrONTo13, 14 study (PRN regimen with monthly monitoring visits following three initial monthly doses) were more promising with VA gains approaching MARINA and ANCHOR results (9.3 letters over 12 months).3, 4, 6, 7, 8 It seems that only regimens with frequent monitoring and strict retreatment criteria can achieve the visual outcomes anywhere near those seen with fixed monthly dosing.

In the meantime, ranibizumab became available for use in routine clinical practice and its effectiveness in real life started to be evaluated. The last few years saw several studies report that outcomes achieved with ranibizumab in clinical practice failed to match the efficacy observed in the early ranibizumab clinical trial programme upon which its license was granted. These include WAVE,17 HELIOS,18 LUMIERE,19 AURA,20 and the MEDISOFT database.21 Interestingly, these studies showed VA gains of 3.8–6.7 letters during the most intensive treatment period (loading period), but unlike MARINA and ANCHOR, these initial visual outcomes were not maintained over time. In fact, most of these studies saw a change in mean VA at 12 months of −1 to 3.2 letters.17, 18, 19, 20, 21 These poor visual outcomes may stem from an inability to adhere to strict a PRN regimen (which is required for PRN to be effective) in routine clinical practice; this hypothesis is supported by the low injection frequency reported by these studies (a mean number of 4.3–5.1 injections over 12 months).17, 19, 20, 21

To better understand the overall picture concerning the real-world effectiveness of ranibizumab, a review of the literature was conducted to identify studies of ranibizumab in clinical practice. This review provides both a summary of the design and methodological quality of the studies and a basic analysis of VA outcomes from the studies.

Materials and methods

Search criteria

We conducted a systematic search of the PubMed database for English language peer-reviewed papers published before 1 December 2014. The search protocol and structure of the review was based on that used by the Cochrane Collaboration. Search terms were as follows: (1) (long-term OR real-life OR longitudinal OR cohort OR clinical experience OR open-label OR real-world OR database OR non-interventional OR non-interventional OR observational) NOT (randomised[ti] OR randomized[ti]); and (2) (wet AMD OR AMD OR exudative AMD OR neovascular AMD); and (3) (ranibizumab[ti] OR Lucentis[ti]).

Further studies to be considered for inclusion were identified by reviewing the references lists from the studies identified during the PubMed search and by assessing relevant papers already known to the authors.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

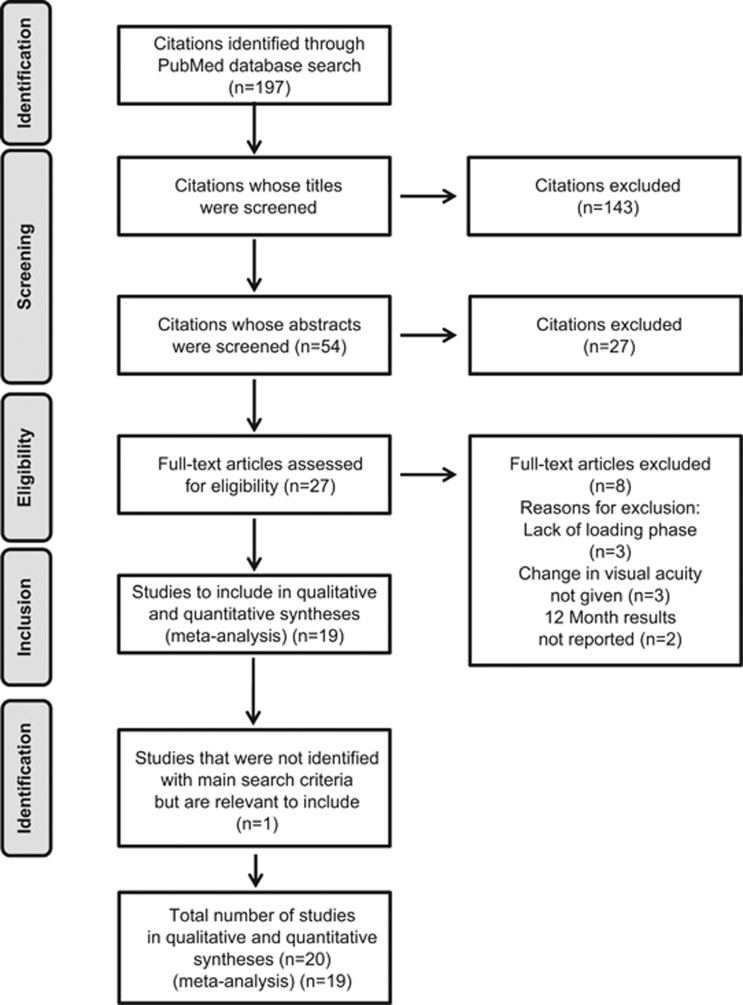

Studies considered for inclusion were screened for eligibility in three sequential stages, by the review of: (1) the title; (2) the abstract, and (3) the full manuscript (Figure 1). At each stage, the rationale for retention or rejection of the study was recorded.

Figure 1.

Study selection flow chart.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: non-randomised controlled studies where treatment was given according to the licensed posology (monthly injections until there are no signs of disease activity and/or maximum VA is achieved, followed by PRN), and where baseline VA and change in VA at 12 months were reported. There were no restrictions on geographic region, clinical characteristics, baseline VA or previous treatment.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: studies that were primarily focused on specific sub-types of wet AMD (eg, polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy or retinal angiomatous proliferation), and studies specifically evaluating switch from other agents (bevacizumab and aflibercept). Follow-up and extensions to Phase III studies were not included as these were not considered real-world studies.

Data analysis

Key outcomes were mean change in VA from baseline and the proportion of patients gaining ≥15 letters or losing ≤15 letters at 12 months. Simple descriptive analyses of these data, including grand means (mean of the means of the several studies) and weighted means (mean weighted against number of eyes per study), were used to pool VA outcomes across the total population. Additional sub-analyses were used to compare visual outcomes according to patient previous treatment history (naive vs non-naive patients), type of study (prospective vs retrospective), and approach to missing data (last observation carried forward). For the purpose of our analysis conversion to Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study letters (ETDRS) letters was carried out in studies providing other measures of VA (eg, logMAR).

Results

Study selection

Figure 1 shows how the studies were selected for inclusion in our analysis. The PubMed search identified a total of 197 citations. Upon screening using our pre-defined inclusion criteria, 143 were discarded after review of the publication titles, 27 were discarded after the review of publication abstracts, and a further 8 were discarded after the review of full text. No additional studies were identified through the review of reference lists within the publications we identified; however, we were aware of an important study (AURA)20 that was not identified by the pre-defined search terms but was relevant to this review. Therefore, 20 studies in total were included in our evaluation.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the 20 real-world studies of ranibizumab included in this review are summarised in Table 1. Most studies were conducted specifically to evaluate the effectiveness of intravitreal ranibizumab for the treatment of wet AMD in a real-world setting; however, the design and endpoints employed to achieve this aim were variable (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Retrospective studies were the most common, with only six having a prospective design. The strengths and weaknesses of the individual studies are summarised in Table 2.

Table 1. Study characteristics: aims, design, and treatment protocols in real-world studies of ranibizumab for the treatment of wet AMD.

| Study | No. of patients | Duration | Country | Aim | Design | Treatment | Treatment-naive? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chavan et al33 | 123 eyes in 120 patients | 36 months | UK | To describe bilateral visual outcomes with ranibizumab, and the effects of incomplete follow-up | Retrospective: data collected from consecutive patients commencing treatment between two defined time points | Loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment on a PRN basis | Yes |

| Cohen et al (LUMIERE)19 | 551 eyes in 551 patients (first eye treated) | 12 months | France | To examine compliance with recommended treatment protocols in a real-world setting, and effects on treatment outcomes | Retrospective: ophthalmologists asked to provide historical data on their first 40–60 patients who had been treated with ranibizumab for ≥12 months | Loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment on a PRN basis | Yes |

| Finger et al (WAVE)a17 | 3470 patients | 12 months | Germany | To evaluate effectiveness, tolerability and safety of repeated injections of ranibizumab in a real-world setting | Prospective: all patients who were recommended for treatment with ranibizumab between two defined time points were included | Loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment on a PRN basis | 75.1% (2605) patients were treatment-naive; 11.7% (405) had received previous intravitreal injections |

| Frennesson and Nilsson25 | 312 eyes in 268 patients (44 patients bilaterally treated) | 36 months | Sweden | To examine the effect of LOCF on visual outcomes in a 3-year study in a real-world setting | Retrospective: data collected from records of all patients who were followed up for 36 months | Loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment on a PRN basis | No (27 eyes had received previous PDT) |

| Gabai et al30 | 100 eyes in 92 patients | 12 months | Italy | To evaluate the safety and efficacy of ranibizumab for the treatment of wet AMD in a real-world setting | Retrospective: examined records of all patients who began treatment with ranibizumab for newly diagnosed wet AMD, with ≥12 months' follow-up | Loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment on a PRN basis | Yes |

| Hjelmqvist et al (Swedish Lucentis Quality Registry)a23 | 471 patients (272 retrospectively and 199 prospectively) | 12 months | Sweden | To evaluate effectiveness of ranibizumab in a real-world setting | Retrospective and prospective components; multicentre | Loading dose of threeinjections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment on a PRN basis | Not specified |

| Holz et al (AURA)20 | 2227 patients in the effectiveness analysis set (1695 patients in the first-year completers' set and 1184 in the second-year completers' set | 24 months | Europe, Canada and Venezuela | To assess the management of patients with wet AMD receiving anti-VEGF treatment in clinical practice between 2009 and 2011 | Retrospective, non-interventional and observational (consecutive screening of patients); multicentre | Treated with ranibizumab as prescribed by physician; 441 patients of the effectiveness set did not have a ranibizumab loading dose and 1786 patients of the effectiveness set did have a ranibizumab loading dose | Not specified |

| Kumar et al34 | 81 eyes in 81 patients (data from first eye treated in 3 patients with bilateral disease) | 12 months | UK | To examine effectiveness of ranibizumab in a real-world setting | Prospective: consecutive recruitment of patients commencing ranibizumab | Loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment on a PRN basis | Yes |

| Matsumiya et al 201322 | 54 patients (24 with tAMD and 30 with PCV) | 12 months | Japan | To compare the outcomes of intravitreal ranibizumab between two different phenotypes of wet AMD | Retrospective, interventional cohort study of consecutive case series | Loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment on a PRN basis | 34 (62.9%) of patients were treatment-naive |

| Muether et al35 | 102 patients (89 followed up for 12 months) | 12 months | Germany | To examine the effects of latency between diagnosis of recurrence and retreatment on outcome | Prospective: consecutive enrolment of patients diagnosed between two defined time points | Loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment on PRN basis (German healthcare funding system introduced a delay of 23.5±10.4 days between indication to treat and treatment) | Yes |

| Nomura et al28 | 123 patients (108 VMA-negative; 15 VMA-positive) | 12 months | Japan | To investigate the effects of VMA on intravitreal ranibizumab treatment in patients with wet AMD | Retrospective comparative study of consecutive patients | Loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment at the discretion of the attending physician | Yes |

| Pagliarini et al (EPICOHORT)27 | 755 patients (133 patients received bilateral treatment) | 24 months | Europe | To assess safety profile of ranibizumab in Europe-wide study in real-world setting | Prospective: enrolment in 54 European clinical centres; Phase IV observational study | For newly diagnosed patients, loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment on PRN basis; for patients with previous treatment, continue ranibizumab PRN | 270 (35.8%) patients reported prior ocular treatment – ranibizumab most common (251; 33.2%) |

| Piermarocchi et al36 | 94 eyes in 94 patients | 12 months | Italy | To investigate whether genetic and non-genetic risk factors influence 12-month response to ranibizumab treatment for wet AMD | Prospective | Loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment on a PRN basis | Yes |

| Pushpoth et al26 | 1086 eyes in 1017 patients | 48 months | UK | To evaluate effectiveness of ranibizumab in a real-world setting | Retrospective: data collected from all patients who began treatment between two defined time points, and who completed ≥24 months' follow-up | Loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment on a PRN basis | 181 eyes had received previous treatment |

| Rakic et al (HELIOS)18 | 309 eyes in 267 patients | 24 months | Belgium | To evaluate effectiveness of ranibizumab in a real-world setting | Prospective, observational, multicentre study | Loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment on a PRN basis | 74.9% treatment-naive |

| Ross et al37 | 406 eyes in 406 patients | 24 months | UK | To define which VA measurements are the best indicators of high-quality care | Retrospective analysis of data collected from treatment-naive patients with ≥12 months' follow-up | Loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment on a PRN basis | Yes |

| Shona et al32 | 87 eyes in 87 patients | 12 months | UK | To evaluate effectiveness of ranibizumab in a real-world setting for patients with differing baseline VA | Retrospective: chart review of treatment-naive patients who initiated ranibizumab; patients divided into three subgroups according to baseline VA: 24–34 letters 35–54 letters ≥55 letters | Loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment on a PRN basis | Yes |

| Tufail et al21 | 12 951 eyes in 11 135 patients | 36 months | UK | To evaluate effectiveness of ranibizumab in a real-world setting and to benchmark standards of care | Retrospective: up to 5 years of routinely collected data were extracted remotely from 14 UK centres using an electronic medical records system; all patients receiving ranibizumab for wet AMD were included | Loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment on a PRN basis | Yes (although prior use of bevacizumab was an exclusion criterion) |

| Williams and Blyth29 | 615 eyes, including 88 eyes with baseline logMAR VA <0.30 | 12 months | UK | To assess the effect of baseline VA on outcome, including among those with baseline VA <0.30 logMAR | Consecutive recruitment of treatment-naive patients; only those with ≥12 months' follow-up included | Loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment on a PRN basis | Yes |

| Zhu et al24 | 886 patients (208 eyes of 208 patients completed the study) | 60 months | Australia | To assess the visual and anatomical outcomes and safety profile of intravitreal ranibizumab in treating wet AMD | Retrospective: consecutive patients treated | Loading dose of three injections (each 0.5 mg), followed by retreatment at the physician's discretion | 71/208 patients were treatment-naive; 137/208 received one or more wet AMD treatments |

Abbreviations: AMD, age-related macular degeneration; LOCF, last observation carried forward; logMAR; logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution; PCV, polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy; PDT, photodynamic therapy; PRN, pro re nata; tAMD, typical age-related macular degeneration; VA, visual acuity; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VMA, vitreomacular adhesion.

Part of LUMINOUS (Holz and colleagues, 2013).

Table 2. Strengths, weaknesses and approaches to missing data in real-world studies of ranibizumab in wet AMD.

| Study | Strengths | Weaknesses | Approach regarding missing values | Attrition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chavan et al33 | Consecutive enrolment to reduce selection bias Separate analysis of data with/without LOCF for patients who discontinued | Relatively small sample size | Separate analysis of data with/without LOCF for patients who discontinued | 30% over 3 years | |

| Cohen et al (LUMIERE)19 | Consecutive enrolment to reduce selection bias | Some ophthalmologists used Snellen system; VA values had to be converted to ETDRS-equivalent values Poor compliance made it difficult to evaluate changes in VA (however, compliance was one of the study outcomes) | Only included patients with 12-month follow-up | NA | |

| Finger et al (WAVE)17 | Relatively large sample size Sample should be broadly representative of those treated with ranibizumab (no additional selection criteria applied at enrolment) | Only about one-third of patients received further injections in the maintenance phase LOCF not applied | Excluded | 25.5% | |

| Frennesson and Nilsson25 | Compared effects on VA outcomes of applying LOCF vs disregarding data from drop-outs | Substantial number of patients received bilateral treatment (not independent samples) | Separate analysis of data with/without LOCF for patients who discontinued | 20.8% | |

| Gabai et al30 | — | — | Only included patients with 12-month follow-up | NA | |

| Hjelmqvist et al (Swedish Lucentis Quality Registry)23 | Both retrospective and prospective components | In 100 of the retrospective patients, Snellen testing was used at baseline and the data were converted to ETDRS values | Excluded | 370/471 patients completed 12 months and formed the ‘on-treatment' population: 21.4% attrition | |

| Holz et al (AURA)20 | Large sample size Real-life assessment of anti-VEGF use Monitoring and visual outcomes in consecutively enroled patients across multiple centres and countries Retrospective design (prevents investigator bias) | Different disease management between countries Clinical centres included in AURA might not represent patient management in the entire country Study limited by the observational and uncontrolled nature of the design | To account for missing data, mean change in VA was assessed using LOCF | Overall 2609 patients: Effectiveness analysis set: 2227 First-year completers' set: 1695 Second-year completers' set: 1184 | |

| Kumar et al34 | Prospective study with monthly clinic attendance | Presence of coexisting ocular pathology or time to treatment from first diagnosis not taken into consideration | Excluded | 80/81 patients received 3 loading injections 2 died (although data available for months 3 and 6, respectively) Further 3 patients lost to follow-up So 75/81 completed=attrition: 7.5% | |

| Matsumiya et al22 | Cohort study of consecutive case series Differential diagnosis of typical AMD and PCV carried out after inclusion To exclude possible influence of previous PDT treatments, visual outcomes were evaluated in sub-population of patients that were treatment-naive | Relatively small sample Possibility of under-treatment | NA | NA | |

| Muether et al35 | Time course of changes in VA tracked | Relatively small sample size | Excluded | 12.7% | |

| Nomura et al28 | Cohort study of consecutive case series | As B-mode ultrasonography was not performed, some eyes with vitreous completely attached to the retina might have been categorised into the VMA (−) group in the analysis The patients were from a single institution (results do not present a general overview of exudative AMD in Japanese patients) | NA | NA | |

| Pagliarini et al (EPICOHORT)27 | Mean BCVA | Heterogeneous patient cohort: some patients had previously been treated with ranibizumab | States in methods that analysis was performed with and without LOCF, but LOCF efficacy results are not reported | 22.8% over 24 months | |

| Piermarocchi et al36 | Mean change in BCVA at study end analysed based on patient's genetic characteristics associated with development of AMD | Relatively limited sample size Need for a more prolonged follow-up Clinical risk factors associated with worse prognosis after treatment were not considered | NA | All patients completed the 12-month follow-up | |

| Pushpoth et al26 | Long duration | High attrition in a long-duration study in an elderly patient group makes later results difficult to interpret | Excluded | No. of patients remaining under follow-up: 12 months: 897/1017 24 months: 730/1017 36 months: 468/730 48 months: 110/217 | |

| Rakic et al (HELIOS)18 | Examined effects of no. of injections in maintenance phase | Data collection began soon after approval of ranibizumab in Belgium; thus, results may not reflect current levels of physician expertise | Excluded | 255 patients evaluable at baseline 24 months: 184 patients Attrition=27.9% | |

| Ross et al37 | Examined effects of baseline VA on outcomes Analysed data with and without LOCF but reported only VA data not change in VA data for LOCF analyses | High attrition | Only included patients with 12-month follow-up Analysed data with and without LOCF but reported only VA data not change in VA data for LOCF analyses | Data extracted on 700 eyes in 629 patients; 247 eyes in 176 patients did not meet eligibility criteria=453 eyes 47 eyes in 47 patients excluded because no data available at 12 months 198 patients completed 24 months Attrition=1 − (198/453)=56.3% | |

| Shona et al32 | Examined effects of baseline VA, and no. of injections, on outcomes | — | Only included patients with 12-month follow-up | NA | |

| Tufail et al21 | Very large sample size | Missing data excluded | Missing data excluded in main analysis. However, data was also analysed separately for eyes that completed 168 weeks, follow-up (n=1138), vs eyes that received ≥1 injection at time 0 (n=12 951) and n=1138 at Week 168 Change in mean VA was similar for the two groups | 12 months: 8598 eyes 24 months: 4990 eyes 36 months: 2470 eyes | |

| Williams and Blyth29 | Examined effectiveness of ranibizumab in patients with relatively high baseline VA | Only patients with 12 months' follow-up included | NA | ||

| Zhu et al24 | Strict inclusion and exclusion criteria Standardised retreatment criteria Long duration Retrospective study of consecutive patients treated for AMD All patients treated by a single physician | Difficulties reporting cataract progression due to non-standardised lens grading at each visit Use of multiple OCT devices ICGA screening for PCV was not performed regularly at baseline (PCV patients might have been included in the study) | NA | All patients included in the study (208) had 5-year VA assessment |

Abbreviations: AMD, age-related macular degeneration; BCVA, best corrected visual acuity; ETDRS, Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study; ICGA, indocyanine green angiography; NA, not applicable; OCT, optical coherence tomography; PDT, photodynamic therapy; VA, visual acuity; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

The size of the studies varied widely, with the number of eyes ranging from 5422 to 12 951.21 In total, 23 261 eyes were included, of which 18 358 had 12-month follow-up data. Approximately half of the studies considered only one eye per patient (generally the first treated eye).

Mean VA at baseline ranged from 48.8 to 61.6 letters, excluding the studies by Shona et al,32 Pushpoth et al,26 and Nomura et al,28 who reported VA outcomes for groups of patients stratified according to different subcategories (eg, baseline VA) but did not report a study mean. The grand mean (mean of the means of the several subsamples) was 54.6±7.3, and when weighted according to the number of eyes in the study was 54.1.

Two of the 20 studies did not provide any information regarding previous treatment history.20, 23 Eleven studies enroled only treatment-naive patients (Table 1), while seven could have included patients who received previous treatment for wet AMD. Previous treatments included photo dynamic therapy (PDT) (n=3)22, 24, 25 and anti-VEGF intravitreal injections (n=4).17, 18, 26, 27

Most studies (n=18) were conducted in a single country, of which 15 were European, 1 was Australian,24 and 2 were Japanese.22, 28 The country with the largest number of studies (n=7) was the UK. The remaining two studies included in the analysis were multinational.

Change in VA

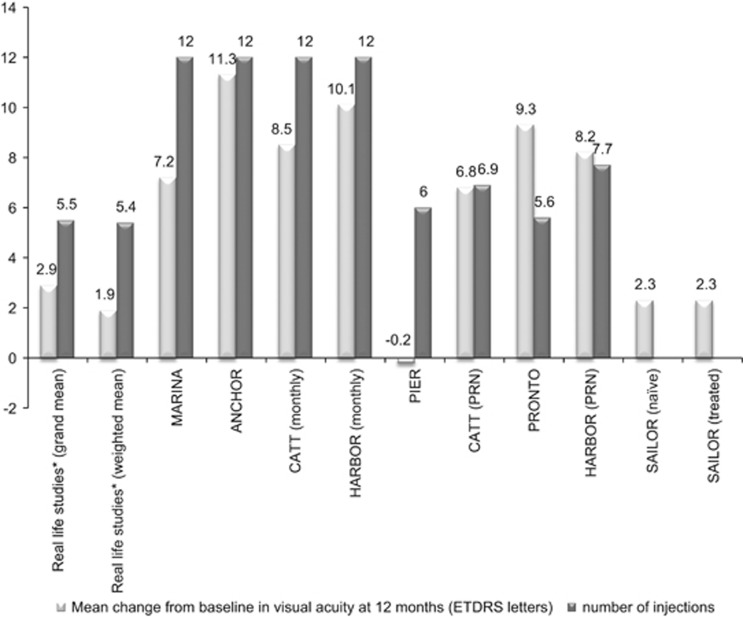

The grand mean (±SD) VA change from baseline to 12 months reported in the 20 studies was 2.9±3.2 letters; however, when weighted according to the number of eyes evaluated, the change was 1.95 letters (Figure 2). Fourteen studies reported an improvement in VA, with a maximum mean gain in VA recorded in a single study of 5.5 letters.29 Two studies reported a decline in visual outcomes with the largest decline in VA of 2.0 letters.30 In the remaining four studies the VA at study end remained similar to baseline values (−0.8 to 0.97 letters).

Figure 2.

Mean change from baseline in visual acuity and number of injections in real-world studies and pivotal randomised controlled studies after 12 months of ranibizumab treatment in patients with wet AMD. *Represents average data for the 20 studies included in the current review (see Table 3).

VA gains in the 12 studies of anti-VEGF-naive patients were slightly greater than that for the full study population, with a grand mean of 3.5±3.9 letters and a weighted mean of 3.5 letters.

Retrospective studies found greater mean gains than prospective studies (grand mean of 3.5±3.5 vs 1.3±1.5 letters; weighted mean of 2.5 letters vs 0 letters). Studies that used a last observation carried forward (LOCF) approach to their data analysis (n=16) reported lower VA gains on average than the full study population (grand mean gain at 12 months of 3.1±3.5 letters; weighted mean 1.9 letters).

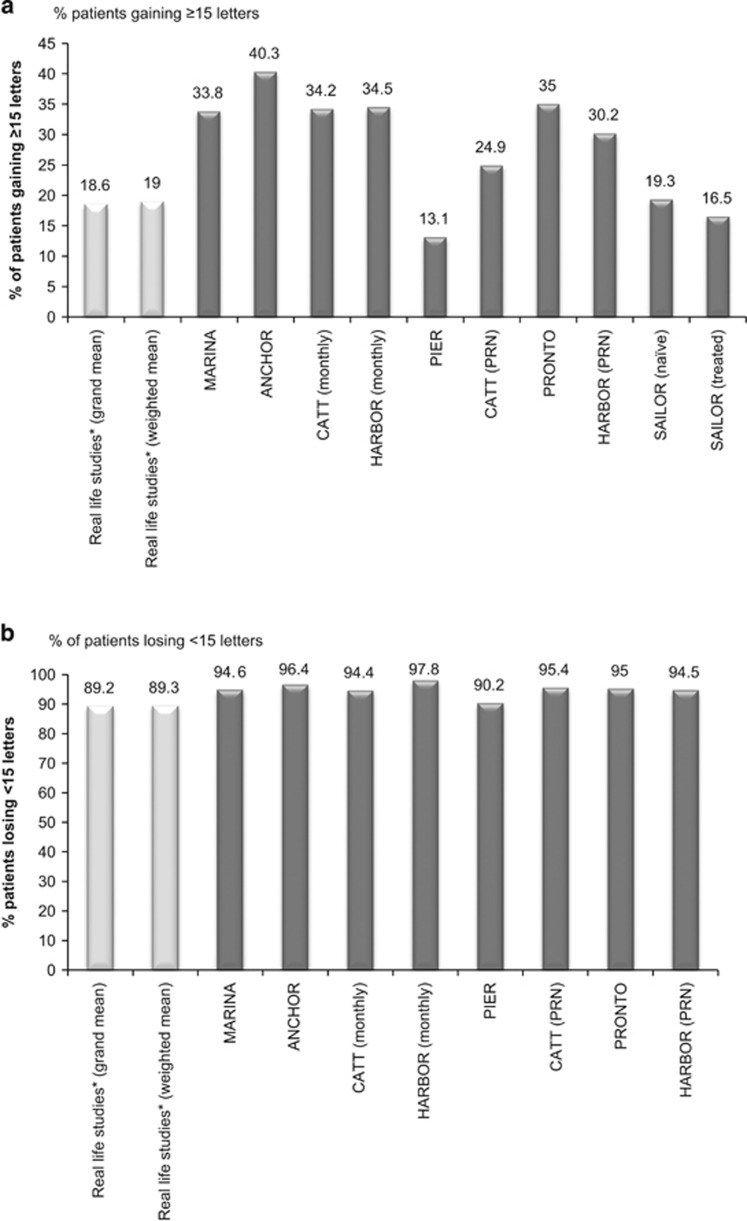

Patients gaining 15 or more letters at 12 months

Eleven studies (including 3869 eyes with 12-month data) reported the percentage of patients gaining ≥15 letters. At 12 months, the means was 19±7.5%. Weighting for the number of eyes available for analysis had little effect (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

(a) Percentage of patients gaining ≥15 letters. *Represents average data for the 11 studies included in the current review which reported this outcome (Table 3). (b) Percentage of patients losing <15 letters. *Represents average data for the 12 studies included in the current review, which reported this outcome (Table 3).

Similar results were observed for the studies of anti-VEGF-naive patients. On average 19±8.4% of these patients gained ≥15 letters (13–24%), with a weighted mean of 20%.

No noteworthy changes were seen in studies reporting LOCF, when compared with the overall analysis.

In retrospective studies, a greater percentage of patients gained ≥15 letters than in prospective studies (grand mean of 19±8.3% and 16±1.4%). Weighting for the number of eyes had little effect with mean values changing to 20% and 15.5%, respectively.

Patients losing 15 letters or less at 12 months

Twelve studies (including 12 467 eyes with 12-month data) reported the percentage of patients losing ≤15 letters. The means±SD at 12 months was 89±6.5% (74.4–97.4%) and was similar to the weighted mean (Figure 3b).

On average, 91±5.9% of anti-VEGF-naive patients lost ≤15 letters. Again, weighting for the number of eyes had little effect (89%).

No noteworthy results were observed in studies reporting LOCF.

Similar results were observed between retrospective and prospective studies regarding the percentage (grand mean) of patients losing ≤15 letters (90±5.2% vs 92±7.4%). No noteworthy differences were found when these changes were weighted for the number of eyes (at 12 months).

Number of injections over 12 months

The mean number of injections ranged from 4.2 to 7.5 (Table 3), with a grand mean (±SD) of 5.5±0.8. Anti-VEGF-naive patients received a similar number of injections to the full study population (grand mean of 5.4±0.7). Weighting for the number of eyes at 12 months had little effect on the outcomes of these analyses.

Table 3. Effects of ranibizumab on key visual acuity outcomes in real-world studies of wet AMD.

| Study | No. of patients | Duration | Country | No. of ranibizumab injections (mean±SD unless otherwise stated) | Baseline visual acuity (mean±SD unless otherwise stated, ETDRS letters unless otherwise stated) | Mean change in visual acuity from baseline to end of study (ETDRS letters unless otherwise stated) | Patients gaining ≥15 letters/3 lines (%) | Patients losing <15 letters/3 lines (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chavan et al 201433 | 123 eyes in 120 patients | 36 months | UK | Full analysis set: Yr 1: 5.9 (1–11) (mean, range) Yr 2: 4.1 (0–10) Yr 3: 4.2 (0–11) Per protocol set: Yr 1: 6.4 (1–11) (mean, range) Yr 2: 4.7 (0–10) Yr 3: 4.2 (0–11) | Full analysis set: 52.89±14.63 Per protocol set: 53.75±13.59 LOCF set: 50.33±17.10 At 12 months: 52.24±14.69 (all treated eyes) | Full analysis set: −1.68±17.76 Per protocol set: +1.47±15.60 LOCF set: −11.03±20.29 At 12 months: −1.34±15.34 | Full analysis set: 16.8% Per protocol set: 19.1% LOCF set: 10% At 12 months: 13% | Full analysis set: 78.2% Per protocol set: 84.3% LOCF set: 60% At 12 months: 84.6% |

| Cohen et al (LUMIERE)19 | 551 eyes in 551 patients | 12 months | France | 5.1 | 53.2±19.3 | +3.2±14.8 | 19.6% | 90.2% |

| Finger et al (WAVE)17 | 3 470 patients | 12 months | Germany | 4.3±0.05 (SEM) | 48.8±18.7 from Holz and colleagues, 2013 0.72±0.01 (SEM) (logMAR of Snellen values) | −0.8 from Holz and colleagues, 2013 +0.02±0.01 (SEM) (logMAR of Snellen values) | — | — |

| Frennesson and Nilsson25 | 312 eyes in 268 patients (44 patients bilaterally treated) | 36 months | Sweden | VA of drop-outs disregarded: Yr 1: 5.4 (CI 5.2–5.7) Yr 2: 2.5 (CI 2.2–2.8) Yr 3: 2.3 (CI 1.7–2.9) LOCF: Yr 1: 5.3 (CI 5.1–5.6) Yr 2: 2.1 (CI 1.8–2.4) Yr 3: 1.9 (CI 1.4–2.4) | 58.4 (CI 56.9–59.9) | VA of drop-outs disregarded: +0.1 [58.5 (CI 54.2–62.8)] LOCF: −4.1 [54.3 (CI 49.6–59.0)] At 12 months: drop-outs disregarded, +1.8; LOCF, +1.0 | VA of drop-outs disregarded: 12.6% Not available for LOCF At 12 months: drop-outs disregarded, 13.7% | VA of drop-outs disregarded: 77.2% Not available for LOCF At 12 months: drop-outs disregarded, 88.3% |

| Gabai et al30 | 100 eyes in 92 patients | 12 months | Italy | 4.8 | 61.6±14.8 | −2.0±17.6 | 16% | 79% |

| Hjelmqvist et al (Swedish Lucentis Quality Registry)23 | 471 patients (272 retrospectively and 199 prospectively) | 12 months | Sweden | 4.7±1.6 (on-treatment population, ie, excluding those who discontinued) | 58.3±12.2 (on-treatment population) | +1.0±13.6 | 14.7% | 74.4% |

| Holz et al (AURA)20 | 2227 patients in the effectiveness analysis set (1695 patients in the first-year completers' set and 1184 in the second-year completers' set | 24 months | Europe, Canada and Venezuela | Effectiveness set: Yr 1: mean of 5.0 Yr 2: mean of 2.2 First-year completers: Yr 1: mean of 5.5 Yr 2: mean of 2.9 Second-year completers: Yr 1: mean of 5.6 Yr 2: mean of 3.5 | Effectiveness set: 55.4±18.4 (n=2147) First-year completers: 56.9±17.8 (n=1642) Second-year completers: 57.2±17.9 (n=1146) | Effectiveness set: Yr 1: +2.4 (LOCF) Yr 2: +0.6 (LOCF) First-year completers: Yr 1: +2.7 Yr 2: +0.3 Second-year completers: Yr 1: +2.7 Yr 2: +0.3 | — | — |

| Kumar et al 201134 | 81 eyes in 81 patients | 12 months | UK | 5.6±2.3 | 49.5±13.4 | +3.7±10.8 | 17.1% | 97.4% |

| Matsumiya et al22 | 54 eyes from 54 patients | 12 months | Japan | 3.9±0.9 in tAMD 4.2±0.9 in PCV group | (logMAR values) 0.60±0.28 for total 0.47±0.26 for PCV 0.53±0.28 for tAMD | Total: 1 month: -0.03 3 months: -0.11 6 months: -0.10 12 months: -0.09 PCV: 1 month: 0 3 months: −0.06 6 months: −0.06 12 months: −0.04 tAMD: 1 month: −0.06 3 months: −0.17 6 months: −0.15 12 months: −0.16 | — | — |

| Muether et al35 | 102 patients [89 followed up for 12 months] | 12 months | Germany | 6.9±2.3 | 58.14±14.55 | +0.66±16.82 | — | — |

| Nomura et al28 | 123 patients: 108 VMA (−); 15 VMA (+) | 12 months | Japan | VMA (−): 5.2 VMA (+): 5.1 | VMA (−): 0.41±0.35 VMA (+): 0.42±0.39 | VMA (−): 6 letters VMA (+): 1.5 letters | — | — |

| Pagliarini et al (EPICOHORT)27 | 755 patients (133 patients received bilateral treatment) | 24 months | Europe | Yr 1: 4.4 Yr 2: 1.8 | 52.8±20.3 | −1.3±0.72 (SEM) At 12 months: +1.5±0.61 (SEM) | — | — |

| Piermarocchi et al36 | 94 eyes of 94 patients | 12 months | Italy | 4.2±1.2 | 59.8±20.3 | 0.97±9.1 | — | — |

| Pushpoth et al26 | 1086 eyes in 1017 patients | 48 months | UK | Pre-treatment: Yr 1: 6.2±2.6 Yr 2: 8.3±3.0 Yr 3: 9.7±4.7 Yr 4: 12.9±7.2 (cumulative totals) Treatment-naive: Yr 1: 5.2±2.7 Yr 2: 8.3±3.7 Yr 3: 10.8±5.8 Yr 4: 12.8±7.8 (cumulative totals) | Month 48: 50.43±15.58 (pre-treatment; n=180) 54.09±15.25 (treatment-naive; n=906) | Month 48: 53.82±15.58 (pre-treatment; n=40) [=+3.39] 58.73±17.19 (treatment-naive; n=75) [+4.64] At 12 months: pre-treatment, +2.67; treatment-naive, +3.82 | Pre-treatment: Month 48: 0.1% (n=4) Treatment-naive: Month 48: 21.3% (n=16) At 12 months: pre-treatment, 20.5% treatment-naive, 20.1% | Pre-treatment: Month 48: 92.5% (n=37) Treatment-naive: Month 48: 81.3% (n=61) At 12 months: pre-treatment, 91.0% treatment-naive, 87.6% |

| Rakic et al (HELIOS)18 | 309 eyes in 267 patients | 24 months | Belgium | Yr 1: 5.0±2.1 Yr 2: 3.7±2.1 | 56.3±14.3 | −2.4±17.4 At 12 months: +1.6±15.6 | 14.1% At 12 months: 15.1% | 81.5% At 12 months: 86.9% |

| Ross et al37 | 406 eyes in 406 patients | 24 months | UK | Yr 1: 5.9 (3–13) Yr 2: 3.6 (0–10) | 54.4±14.2 | +1.6±17.6 At 12 months: +4.1±14.2 | 20.7% At 12 months: 20.9% | 86.7% At 12 months: 90.1% |

| Shona et al32 | 87 eyes in 87 patients | 12 months | UK | Baseline VA: Good: 5.7 Medium: 6.1 Poor: 5.3 | Good: 61.67±6.21 Medium: 43.79±4.67 Poor: 28.93±4.7 | Good: +2.85 Medium: +7.10 Poor: +14.00 | Good: 10% Medium: 14% Poor: 41% | Good: 95% Medium: 92% Poor: 100% |

| Tufail et al21 | 12 951 eyes in 11 135 patients | 36 months | UK | Yr 1: 5.7 (1–13) Yr 2: 3.7 (0–13) Yr 3: 3.7 (0–12) | For eyes with ≥36 months' follow-up: 55 letters | For eyes with ≥36 months' follow-up: −2 letters at Week 156 At 12 months: +2.0 | — | 82% At 12 months: 90% |

| Williams and Blyth29 | 615 eyes, including 88 eyes with baseline VA <0.30 | 12 months | UK | All: 5.6 Baseline VA: <0.30: 5.4 0.30–0.59: 5.6 0.60–0.99: 5.8 1.00–1.20: 5.2 | All: 0.60 (logMAR) Baseline VA (logMAR): <0.30 (mean 0.19) 0.30–0.59 (mean 0.42) 0.60–0.99 (mean 0.73) 1.00–1.20 (mean 1.06) Baseline VA (ETDRS) <0.30 (mean 75.48) 0.30–0.59 (mean 63.84) 0.60–0.99 (mean 48.58) 1.00–1.20 (mean 31.97) | All: 0.49 (logMAR) Baseline VA (logMAR): <0.30: 0.20 0.30–0.59: 0.37 0.60–0.99: 0.60 1.00–1.20: 0.76 Baseline VA (ETDRS) <0.30: −0.69 0.30–0.59: +2.61 0.60–0.99: +6.32 1.00–1.20: +15.05 | All: 24% Baseline VA: <0.30: 1% 0.30–0.59: 16% 0.60–0.99: 33% 1.00–1.20: 46% | All: 92% Baseline VA: <0.30: 93% 0.30–0.59: 88% 0.60–0.99: 92% 1.00–1.20: 100% |

| Zhu et al24 | 886 patient (208 eyes of 208 patients completed the study) | 60 months | Australia | Yr 1: 7.5±2.6 Yr 2: 5.8±3.9 Yr 3: 6.4±4.5 Yr 4: 5.6±4.5 Yr 5: 5.8±4.7 | 53.6±19.3 (208 patients) | Month 6: +3.2±10.4 Yr 1: +1.9 Yr 5: -2.4 | — | — |

Abbreviations: AMD, age-related macular degeneration; CI, confidence interval; ETDRS, Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study; LOCF, last observation carried forward; logMAR; logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution; PCV, polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy; tAMD, typical age-related macular degeneration; VA, visual acuity; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; Yr, year.

Similar number of injections were received by patients in the retrospective and prospective studies (grand mean number of injections of 5.6±0.7 and 5.1±1, respectively). In this analysis, weighting according to the number of eyes assessed at 12 months gave different results, showing that patients treated in prospective studies received one less injection on average than those evaluated by retrospective studies (4.5 vs 5.7 injections).

Other outcomes

Ten studies reported mean changes in central retinal thickness, six reported safety data and three reported vision-related quality of life. A detailed overview of these and other outcomes is provided for reference in Supplementary Table 1.

Discussion

This review was performed in order to determine whether, in patients with wet AMD, real-world outcomes achieved with ranibizumab match the positive outcomes reported in the pivotal ranibizumab trials,3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9 and subsequent studies of 0.5 mg PRN regimens.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16

The grand mean (+2.9 letters) and weighted mean (+1.95 letters) calculated from the changes in VA reported at 12 months in the trials included in this review are considerably lower than those reported in the pivotal studies of ranibizumab (fixed monthly dosing),3, 4, 6, 7, 8 with the exception of the PIER study9, 31 (fixed quarterly dosing) that showed a mean loss of 0.2 letters. Specifically, the recently published AURA study conducted in multiple countries and considered a true and current depiction of the real-world use of ranibizumab for the treatment of AMD, clearly demostrated that the VA outcomes are far worse than the ones reported in the landmark trials (MARINA and ANCHOR).3, 4, 6, 7, 8 Rather, they are more in line with those observed in PIER9, 31 and SAILOR,10 which used less intensive treatment schedules (fixed quarterly dosing and PRN dosing based on a quarterly monitoring schedule, respectively), and compare unfavourably with MARINA4, 6, 7 and ANCHOR.3, 8

What are the factors that underlie the reduced effectiveness of ranibizumab in clinical practice? A key consideration may be the reduced number of injections that patients receive in clinical practice. Across the 20 real-world studies included in the present review, the mean number of injections ranged from 4.2–7.5; the grand mean at 12 months was 5.5±0.8 injections and the weighted mean was 5.4 injections, notably less than the 12 injections received in ANCHOR/MARINA3, 4, 6, 7, 8 (fixed monthly dosing). A reduced number of injections in the real-world setting is not unexpected as adherence to treatment regimens tends to be harder to maintain owing to the challenges of implementing intensive treatment regimens outside of the clinical trial setting. However, the reduced efficacy of ranibizumab in real-world practice observed in our study cannot be explained simply by the reduced number of injections, as the pooled mean values were: (1) less than the 0.5 mg PRN arms of CATT11, 12 and HARBOUR (6.9 and 7.7 injections, respectively),15, 16 which saw greater increases in VA; (2) similar to PrONTO (5.6 injections),13, 14 which demonstrated a greater increase in VA; and (3) greater than in SAILOR (4.6 injections),10 which showed a similar increase in VA as observed in the present analysis (see Figure 2 for change in VA from baseline).

Besides the reduced number of injections, the schedule on which they are given as well as the monitoring frequency and retreatment criteria might also be a reason for the limited efficacy of ranibizumab in the clinic. The studies in this and previous analyses typically employed PRN regimens as a means of appropriately managing treatment burden. By definition, a PRN regimen only treats patient with symptomatic disease; hence, it is possible that recurring fluid may cause progressive damage. Results from CATT11, 12 and HARBOUR15, 16 show that it is possible to achieve good visual outcomes with a PRN regimen when frequent regimented monitoring visits and strict retreatment criteria are in place. However, with less intensive monitoring, as seen in the SAILOR study (quarterly monitoring schedule)10 and in routine clinical practice as per the ranibizumab label, visual outcomes using PRN are poor.

Recently, the treat-and-extend regimen has emerged as a potential alternative method of delivering the best-possible visual outcomes, with the appropriate injection frequency, while minimising the treatment burden. With treat-and-extend, the physician can identify the appropriate injection frequency for each patient, proactively injecting at each visit and deciding when to treat next rather than whether to treat at that time. Thus, treatment remains ahead of the disease. In the future, it will be interesting to evaluate whether this newer treatment approach can improve outcomes in the real-life situation.

Baseline VA is an additional determinant of outcome in terms of VA gains (ceiling effect), with patients with poorer vision tending to show more gain. However, the mean baseline acuity of the studies included in the present analysis is comparable to that reported in the clinical trials (respective ranges 48.8–61.6 vs 47.1–61.5) with the grand mean (54.6) and weighted mean (54.1) lying in the centre of these values. Therefore, it is difficult to ascribe the poorer outcomes observed in the present analysis to baseline acuity alone.

As with any review of this type, it is important to consider the limitations of the current analysis. By their nature, real-world studies (non-randomised and not controlled studies) are not as rigorously designed as clinical trials and therefore require careful interpretation. In particular, 13 out of the 20 included studies, including the largest study by Tufail et al,21 were retrospective. Data may be incomplete, with patients being lost to follow-up or not having outcomes recorded at appropriate time points. Some studies employed an LOCF method to account for these missing data; although a standard and valid technique, LOCF analysis may skew study results particularly in conditions that change over time, for example, wet AMD. Morevover, differences in VA measurements in real-lide studies vs clinical trials (Snellen vs ETDRS) could also be considered as a limitation.

In addition, the inclusion criteria vary across studies included in the present analysis, with many including patients irrespective of their treatment history or baseline VA. Such variability can affect outcomes. For example, patients with good baseline acuity demonstrated a smaller improvement in response to ranibizumab than patients with poor baseline acuity,29, 32 while treatment-naive patients showed a better response than previously treated individuals.26 Differences such as these may obscure the effects of treatment if the numbers of patients from a particular group are unrepresentative of the population as a whole. However, with nearly 20 000 patients analysed, the real-life data reviewed here could be considered as representative of current practice.

From an analytical perspective, the validity of data pooling across studies with different designs is inherently limited. The strengths and weaknesses of each of the 20 real-world studies included in the review, along with a description of the approaches adopted to missing values in the studies, are summarised in Table 2.

Finally, only peer-reviewed studies indexed on PubMed were included. It is possible that additional relevant studies not listed on PubMed are not captured here.

In conclusion, the current review strongly suggests that, in patients with wet AMD, VA outcomes achieved with ranibizumab in clinical practice do not match those reported in pivotal studies. Although factors such as reduced injection frequency and patient heterogeneity are likely to have a part in this phenomenon, further research is required to determine the reasons for this discrepancy. Nonetheless, clinicians should be aware of this discrepancy when consenting patients for receiving ranibizumab for wet AMD.

Acknowledgments

I take full responsibility for the scope, direction, and the content of the manuscript, and has approved the submitted manuscript. Medical writing assistance was provided by Ana Tadeu of Porterhouse Medical Ltd., and was funded by Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Eye website (http://www.nature.com/eye)

VC is a consultant for Allergan, Bayer, Novartis, Quantel Medical, Pfenex.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1Stewart MW. Clinical and differential utility of VEGF inhibitors in wet age-related macular degeneration: focus on aflibercept. Clin Ophthalmol 2012; 6: 1175–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2Kawasaki R, Yasuda M, Song SJ, Chen SJ, Jonas JB, Wang JJ et al. The prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in Asians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2010; 117(5): 921–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, Soubrane G, Heier JS, Kim RY et al. Ranibizumab vs verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med 2006; 355(14): 1432–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, Boyer DS, Kaiser PK, Chung CY et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med 2006; 355(14): 1419–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5Blick SK, Keating GM, Wagstaff AJ. Ranibizumab. Drugs 2007; 67(8): 1199–1206 discussion 1207-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6Chang TS, Bressler NM, Fine JT, Dolan CM, Ward J, Klesert TR. Improved vision-related function after ranibizumab treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: results of a randomized clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2007; 125(11): 1460–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7Kaiser PK, Blodi BA, Shapiro H, Acharya NR. Angiographic and optical coherence tomographic results of the MARINA study of ranibizumab in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2007; 114(10): 1868–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8Brown DM, Michels M, Kaiser PK, Heier JS, Sy JP, Ianchulev T. Ranibizumab vs verteporfin photodynamic therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Two-year results of the ANCHOR study. Ophthalmology 2009; 116(1): 57–65 e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9Regillo CD, Brown DM, Abraham P, Yue H, Ianchulev T, Schneider S et al. Randomized, double-masked, sham-controlled trial of ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: PIER Study year 1. Am J Ophthalmol 2008; 145(2): 239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10Boyer DS, Heier JS, Brown DM, Francom SF, Ianchulev T, Rubio RG. A Phase IIIb study to evaluate the safety of ranibizumab in subjects with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2009; 116(9): 1731–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11Martin DF, Maguire MG, Ying GS, Grunwald JE, Fine SL, Jaffe GJ. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(20): 1897–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12Martin D, Maguire M, Fine SL, Ying GS, Jaffe GJ, Grunwald JE et al. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: two-year results. Ophthalmology 2012; 119: 1388–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13Lalwani GA, Rosenfeld PJ, Fung AE, Dubovy SR, Michels S, Feuer W et al. A variable-dosing regimen with intravitreal ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: year 2 of the PrONTO Study. Am J Ophthalmol 2009; 148(1): 43–58 e41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14Fung AE, Lalwani GA, Rosenfeld PJ, Dubovy SR, Michels S, Feuer WJ et al. An optical coherence tomography-guided, variable dosing regimen with intravitreal ranibizumab (Lucentis) for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol 2007; 143(4): 566–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15Busbee BG, Ho AC, Brown DM, Heier JS, Suner IJ, Li Z et al. Twelve-month efficacy and safety of 0.5mg or 2.0mg ranibizumab in patients with subfoveal neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2013; 120(5): 1046–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16Ho AC, Busbee BG, Regillo CD, Wieland MR, Van Everen SA, Li Z et al. Twenty-four-month efficacy and safety of 0.5mg or 2.0mg ranibizumab in patients with subfoveal neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2014; 121(11): 2181–2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17Finger RP, Wiedemann P, Blumhagen F, Pohl K, Holz FG. Treatment patterns, visual acuity and quality-of-life outcomes of the WAVE study—A noninterventional study of ranibizumab treatment for neovascular age-related macular degeneration in Germany. Acta Ophthalmol 2013; 91(6): 540–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18Rakic JM, Leys A, Brie H, Denhaerynck K, Pacheco C, Vancayzeele S et al. Real-world variability in ranibizumab treatment and associated clinical, quality of life, and safety outcomes over 24 months in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration: the HELIOS study. Clin Ophthalmol 2013; 7: 1849–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19Cohen SY, Mimoun G, Oubraham H, Zourdani A, Malbrel C, Quere S et al. Changes in visual acuity in patients with wet age-related macular degeneration treated with intravitreal ranibizumab in daily clinical practice: the LUMIERE study. Retina 2013; 33(3): 474–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20Holz FG, Tadayoni R, Beatty S, Berger A, Cereda MG, Cortez R et al. Multi-country real-life experience of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy for wet age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol 2014; 99: 220–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21Tufail A XW, Johnston R, Akerele T, McKibbin M, Downey L, Natha S, Chakravarthy U, Bailey C, Khan R, Antcliff R, Armstrong S, Varma A, Kumar V, Tsaloumas M, Mandal K, Bunce C. The neovascular age-related macular degeneration database: multicenter study of 92 976 ranibizumab injections: report 1: visual acuity. Ophthalmology 2014; 121(5): 1092–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22Matsumiya W, Honda S, Kusuhara S, Tsukahara Y, Negi A. Effectiveness of intravitreal ranibizumab in exudative age-related macular degeneration (AMD): comparison between typical neovascular AMD and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy over a 1 year follow-up. BMC ophthalmology 2013; 13: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23Hjelmqvist L, Lindberg C, Kanulf P, Dahlgren H, Johansson I, Siewert A. One-year outcomes using ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: results of a prospective and retrospective observational multicentre study. Journal of ophthalmology 2011; 2011: 405724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24Zhu M, Chew JK, Broadhead GK, Luo K, Joachim N, Hong T et al. Intravitreal Ranibizumab for neovascular Age-related macular degeneration in clinical practice: five-year treatment outcomes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2015; 253(8): 1217–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25Frennesson CI, Nilsson SE. A three-year follow-up of ranibizumab treatment of exudative AMD: impact on the outcome of carrying forward the last acuity observation in drop-outs. Acta Ophthalmol 2014; 92(3): 216–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26Pushpoth S, Sykakis E, Merchant K, Browning AC, Gupta R, Talks SJ. Measuring the benefit of 4 years of intravitreal ranibizumab treatment for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol 2012; 96(12): 1469–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27Pagliarini S, Beatty S, Lipkova B, Perez-Salvador Garcia E, Reynders S, Gekkieva M et al. A 2-year, phase IV, multicentre, observational study of ranibizumab 0.5mg in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration in routine clinical practice: The EPICOHORT Study. J Ophthalmol 2014; 2014: 857148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28Nomura Y, Takahashi H, Tan X, Fujimura S, Obata R, Yanagi Y. Effects of vitreomacular adhesion on ranibizumab treatment in Japanese patients with age-related macular degeneration. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2014; 58(5): 443–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29Williams TA, Blyth CP. Outcome of ranibizumab treatment in neovascular age related macula degeneration in eyes with baseline visual acuity better than 6/12. Eye (Lond) 2011; 25(12): 1617–1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30Gabai A, Veritti D, Lanzetta P. One-year outcome of ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a thorough analysis in a real-world clinical setting. Eur J Ophthalmol 2014; 24(3): 396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31Abraham P, Yue H, Wilson L. Randomized, double-masked, sham-controlled trial of ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: PIER study year 2. Am J Ophthalmol 2010; 150(3): 315–324 e311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32Shona O, Gupta B, Vemala R, Sivaprasad S. Visual acuity outcomes in ranibizumab-treated neovascular age-related macular degeneration; stratified by baseline vision. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2011; 39(1): 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33Chavan R, Panneerselvam S, Adhana P, Narendran N, Yang Y. Bilateral visual outcomes and service utilization of patients treated for 3 years with ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Clin Ophthalmol 2014; 8: 717–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34Kumar A, Sahni JN, Stangos AN, Campa C, Harding SP. Effectiveness of ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration using clinician-determined retreatment strategy. Br J Ophthalmol 2011; 95(4): 530–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35Muether PS, Hoerster R, Hermann MM, Kirchhof B, Fauser S. Long-term effects of ranibizumab treatment delay in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2013; 251(2): 453–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36Piermarocchi S, Miotto S, Colavito D, Leon A, Segato T. Combined effects of genetic and non-genetic risk factors affect response to ranibizumab in exudative age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol 2015; 93(6): e451–e457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37Ross AH, Donachie PH, Sallam A, Stratton IM, Mohamed Q, Scanlon PH et al. Which visual acuity measurements define high-quality care for patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration treated with ranibizumab? Eye (Lond) 2013; 27(1): 56–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.