Abstract

Plant-microbe interactions in the rhizosphere are the determinants of plant health, productivity and soil fertility. Plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) are bacteria that can enhance plant growth and protect plants from disease and abiotic stresses through a wide variety of mechanisms; those that establish close associations with plants, such as the endophytes, could be more successful in plant growth promotion. Several important bacterial characteristics, such as biological nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, ACC deaminase activity, and production of siderophores and phytohormones, can be assessed as plant growth promotion (PGP) traits. Bacterial inoculants can contribute to increase agronomic efficiency by reducing production costs and environmental pollution, once the use of chemical fertilizers can be reduced or eliminated if the inoculants are efficient. For bacterial inoculants to obtain success in improving plant growth and productivity, several processes involved can influence the efficiency of inoculation, as for example the exudation by plant roots, the bacterial colonization in the roots, and soil health. This review presents an overview of the importance of soil-plant-microbe interactions to the development of efficient inoculants, once PGPB are extensively studied microorganisms, representing a very diverse group of easily accessible beneficial bacteria.

Keywords: nitrogen fixation, siderophore production, plant-bacteria interaction, inoculant, rhizosphere

Introduction

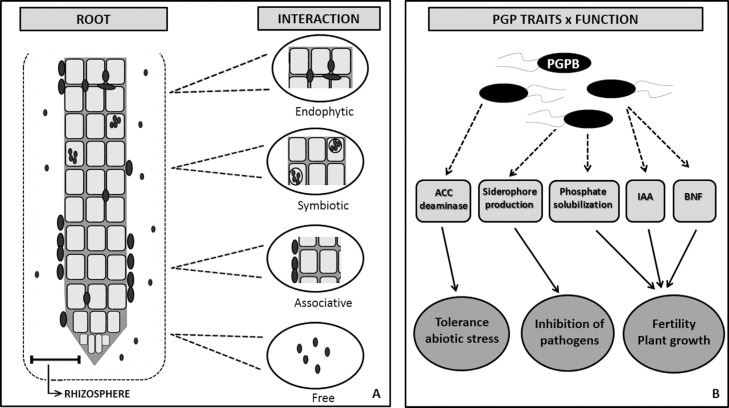

The rhizosphere can be defined as the soil region where processes mediated by microorganisms are specifically influenced by the root system (Figure 1A). This area includes the soil connected to the plant roots and often extends a few millimeters off the root surface, being an important environment for the plant and microorganism interactions (Lynch, 1990; Gray and Smith, 2005), because plant roots release a wide range of compounds involved in attracting organisms which may be beneficial, neutral or detrimental to plants (Lynch, 1990; Badri and Vivanco, 2009). The plant growth-promoting bacteria (or PGPB) belong to a beneficial and heterogeneous group of microorganisms that can be found in the rhizosphere, on the root surface or associated to it, and are capable of enhancing the growth of plants and protecting them from disease and abiotic stresses (Dimkpa et al., 2009a; Grover et al., 2011; Glick, 2012). The mechanisms by which PGPB stimulate plant growth involve the availability of nutrients originating from genetic processes, such as biological nitrogen fixation and phosphate solubilization, stress alleviation through the modulation of ACC deaminase expression, and production of phytohormones and siderophores, among several others.

Figure 1. Rhizosphere/bacteria interactions. A) Different types of association between plant roots and beneficial soil bacteria; B) After colonization or association with roots and/or rhizosphere, bacteria can benefit the plant by (i) tolerance toward abiotic stress through action of ACC deaminase; (ii) defense against pathogens by the presence of competitive traits such as siderophore production; (iii) increase of fertility and plant growth through biological nitrogen fixation (BNF), IAA (indole-3-acetic acid) production, and phosphate solubilization around roots.

Interactions between plants and bacteria occur through symbiotic, endophytic or associative processes with distinct degrees of proximity with the roots and surrounding soil (Figure 1A). Endophytic PGPB are good inoculant candidates, because they colonize roots and create a favorable environment for development and function. Non-symbiotic endophytic relationships occur within the intercellular spaces of plant tissues, which contain high levels of carbohydrates, amino acids, and inorganic nutrients (Bacon and Hinton, 2006).

Agricultural production currently depends on the large-scale use of chemical fertilizers (Wartiainen et al., 2008; Adesemoye et al., 2009). These fertilizers have become essential components of modern agriculture because they provide essential plant nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium. However, the overuse of fertilizers can cause unanticipated environmental impacts (Shenoy et al., 2001; Adesemoye et al., 2009). To achieve maximum benefits in terms of fertilizer savings and better growth, the PGPB-based inoculation technology should be utilized along with appropriate levels of fertilization. Moreover, the use of efficient inoculants can be considered an important strategy for sustainable management and for reducing environmental problems by decreasing the use of chemical fertilizers (Alves et al., 2004; Adesemoye et al., 2009; Hungria et al., 2010, 2013).

The success and efficiency of PGPB as inoculants for agricultural crops are influenced by various factors, among which the ability of these bacteria to colonize plant roots, the exudation by plant roots and the soil health. The root colonization efficiency of PGPB is closely associated with microbial competition and survival in the soil, as well as with the modulation of the expression of several genes and cell-cell communication via quorum sensing (Danhorn and Fuqua, 2007; Meneses et al., 2011; Alquéres et al., 2013; Beauregard et al., 2013). Plant roots react to different environmental conditions through the secretion of a wide range of compounds which interfere with the plant-bacteria interaction, being considered an important factor in the efficiency of the inoculants (Bais et al., 2006; Cai et al., 2009, 2012; Carvalhais et al., 2013). Soil health is another important factor that affects the inoculation efficiency, due to several characteristics such as soil type, nutrient pool and toxic metal concentrations, soil moisture, microbial diversity, and soil disturbances caused by management practices.

Mechanisms of Plant Growth Promotion

The mechanisms by which bacteria can influence plant growth differ among species and strains, so typically there is no single mechanism for promoting plant growth. Studies have been conducted regarding the abilities of various bacteria to promote plant growth, among them the endophytic bacteria. Endophytes are conventionally defined as bacteria or fungi that colonize internal plant tissues, can be isolated from the plant after surface disinfection and cause no negative effects on plant growth (Gaiero et al., 2013). Many bacteria promote plant growth at various stages of the host plant life cycle through different mechanisms (Figure 1B). Here we discuss five important mechanisms of PGPB.

Biological nitrogen fixation

All organisms require nitrogen (N) to synthesize biomolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids. However, the main source of N in nature, the atmospheric nitrogen (N2), is not accessible to most living organisms, including eukaryotes. Biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) is the process responsible for the reduction of N2 to ammonia (NH3) (Newton, 2000; Franche et al., 2009) and is performed in diazotrophic microorganisms, particularly bacteria and archaea (Dixon and Kahn, 2004).

Diazotrophic microorganisms perform BNF through nitrogenase, a highly conserved enzyme that comprises two metalloproteins, FeMo-protein and Fe-protein (Dixon and Kahn, 2004). Although there are many morphological, physiological and genetic differences between the diazotrophics, as well as an enormous variability of environments where they can be found, they all contain the enzyme nitrogenase (Moat and Foster, 1995; Boucher et al., 2003; Zehr et al., 2003; Dixon and Kahn, 2004). Klebsiella oxytoca M5a1 was the first diazotrophic bacterium that had the genes involved in the synthesis and functioning of nitrogenase (nif, N2 fixation) identified and characterized. In the genome of this bacterium, 20 nif genes are grouped in a 24-kb chromosomal region, organized into 8 operons: nifJ, nifHDKTY, nifENX, nifUSVWZ, nifM, nifF, nifLA, and nifBQ (Arnold et al., 1988). The nifD and nifK genes encode the FeMo-protein, and nifH encodes the Fe-protein (Boucher et al., 2003).

Among the leguminous plants of the Fabaceae family, the soil bacteria of the Rhizobiaceae (rhizobia) family are confined to the root nodules (Willems, 2007). Within these nodules, rhizobia effectively perform BNF through the adequate control of the presence of oxygen, an inhibitor of nitrogenase activity (Dixon and Kahn, 2004; Shridhar, 2012). Many species of microorganisms are used in the cultivation of plants of economic interest, facilitating the host plant growth without the use of nitrogenous fertilizers. For instance, the production of soybean (Glycine max L.) in Brazil is an excellent example of the efficiency of BNF through the use of different strains of Bradyrhizobium sp., such as B. japonicum and B. elkanii (Alves et al., 2004; Torres et al., 2012). The importance of endophytic N2-fixing bacteria has also been the object of studies in non-leguminous plants such as sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.; Thaweenut et al., 2011). Other studies have suggested that bradyrhizobia colonize and express nifH not only in the root nodules of leguminous plants but also in the roots of sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas L.), acting as diazotrophic endophytes (Terakado-Tonooka et al., 2008).

Herbaspirillum sp. is a gram-negative bacterium associated with important agricultural crops, such as rice (Oryza sativa L.; Pedrosa et al., 2011; Souza et al., 2013), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.; James et al., 1997), maize (Zea mays L.; Monteiro et al., 2008), and sugarcane (Pedrosa et al., 2011). Fluorescence and electron microscopy have revealed that the Herbaspirillum sp. strain B501 colonizes the intercellular spaces of wild rice (Oryza officinalis) leaves, fixing N2 in vivo (Elbeltagy et al., 2001), and expresses nif genes in wild rice shoots (You et al., 2005). This same strain also colonizes the intercellular spaces of the roots and stem tissues of sugarcane plants, showing non-specificity to the host plant (Njoloma et al., 2006). Inoculations of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) and Miscanthus plants with a strain of H. frisingense showed that this bacterium is a true plant endophyte (Rothballer et al., 2008).

The PGPB related to genus Azospirillum have been largely studied because of their efficiency in promoting the growth of different plants of agronomical interest. Garcia de Salamone et al. (1996) showed that Azospirillum sp. contribute to plant fitness through BNF. The genus Burkholderia also includes species that fix N2. B. vietnamiensis, a human pathogenic species, was efficient in colonizing rice roots and fixing N2 (Govindarajan et al., 2008). In addition to Burkholderia, the potential of BNF and endophytic colonization of bacteria belonging to the genera Pantoea, Bacillus and Klebsiella was also confirmed in different maize genotypes (Ikeda et al., 2013). Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus is another well-studied endophyte (Baldani et al., 1997; Oliveira et al., 2002; Muthukumarasamy et al., 2005; Bertalan et al., 2009). In conditions of N deficiency, the G. diazotrophicus strain Pal5 isolated from sugarcane is able to increase the N content when compared with plants inoculated with a Nif− mutant or uninoculated plants (Sevilla et al., 2001).

Production of indolic compounds

The influence of bacteria in the rhizosphere of plants is largely due to the production of auxin phytohormones (Spaepen et al., 2007). Several bacterial species can produce indolic compounds (ICs) such as the auxin phytohormone indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), which present great physiological relevance for bacteria-plant interactions, varying from pathogenesis to phytostimulation (Spaepen et al., 2007). The ability to produce ICs is widely distributed among plant-associated bacteria. Souza et al. (2013) demonstrated that approximately 80% of bacteria isolated from the rhizosphere of rice produce ICs. Other studies have shown that rhizosphere bacteria produce more ICs than bulk soil bacteria (Khalid et al., 2004), and in a recent study Costa et al. (2014) showed that this effect was also observed in endophytic bacteria, demonstrating high IC production in the Enterobacteriaceae family (Enterobacter, Escherichia, Grimontella, Klebsiella, Pantoea, and Rahnella).

The synthesis of ICs in bacteria depends on the presence of precursors in root exudates. Among the various exudates, L-tryptophan has been identified as the main precursor for the route of IC biosynthesis in bacteria. The characterization of intermediate compounds has led to the identification of different pathways that use L-tryptophan as the main precursor. The different pathways of IAA synthesis in bacteria show a high degree of similarity with the IAA biosynthesis pathways in plants (Spaepen et al., 2007). Beneficial bacteria predominantly synthesize IAA via the indole-3-pyruvic acid pathway, an alternative pathway dependent on L-tryptophan. In phytopathogenic bacteria, IAA is produced from L-tryptophan via the indol-acetoamide pathway. In A. brasilense, at least three biosynthesis pathways have been described for the production of IAA: two L-tryptophan-dependent (indole-3-pyruvic acid and indole-acetoamide pathways) and one L-tryptophan-independent (Prinsen et al., 1993), with the indole-3-pyruvic acid pathway as the most important among them (Spaepen et al., 2008).

The potential of rhizobia to establish symbiosis with legumes has been well documented; however, studies have indicated the importance of IAA in nodulation events. The co-inoculation of beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.; cultivar DOR364) with A. brasilense Sp245 and Rhizobium etli CNPAF512 yielded a greater number of nodules; however, the results obtained using a mutant strain of Azospirillum that produced only 10% of the IAA of the wild-type strain were not satisfactory, indicating the importance of bacterial IAA in the establishment and efficiency of symbiosis (Remans et al., 2008). IAA-producing Azospirillum sp. also promoted alterations in the growth and development of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants (Dobbelaere et al., 1999; Akbari et al., 2007; Spaepen et al., 2008; Baudoin et al., 2010).

Soil microorganisms are capable of synthesizing and catabolizing IAA. The capacity of catabolizing IAA has been well characterized in B. japonicum (Jensen et al., 1995) and Pseudomonas putida 1290 (Leveau and Lindow, 2005). P. putida 1290 uses IAA as the sole source of carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and energy. In addition to the utilization of IAA, strain 1290 also produced IAA in culture medium supplemented with L-tryptophan. In co-inoculation experiments in radish (Raphanus sativus L.) roots, this strain minimized the negative effects of high IAA concentrations produced by the pathogenic bacteria Rahnella aquaticus and P. syringae. In this context, microorganisms that catabolize IAA might also positively affect the growth of plants and prevent pathogen attack (Leveau and Lindow, 2005).

Siderophore production

Iron (Fe) is an essential micronutrient for plants and microorganisms, as it is involved in various important biological processes, such as photosynthesis, respiration, chlorophyll biosynthesis (Kobayashi and Nishizawa, 2012), and BNF (Dixon and Kahn, 2004). In anaerobic and acidic soils, such as flooded soils, high concentrations of ferrous (Fe2+) ions generated through the reduction of ferric (Fe3+) ions might lead to iron toxicity due to excessive Fe uptake (Stein et al., 2009). Under aerobic conditions, iron solubility is low, reflecting the predominance of Fe3+ typically observed as oxyhydroxide polymers, thereby limiting the Fe supply for different forms of life, particularly in calcareous soils (Andrews et al., 2003; Lemanceau et al., 2009). Microorganisms have developed active strategies for Fe uptake. Bacteria can overcome the nutritional Fe limitation by using chelator agents called siderophores. Siderophores are defined as low-molecular-mass molecules (< 1000 Da) with high specificity and affinity for chelating or binding Fe3+, followed by the transportation and deposition of Fe within bacterial cells (Neilands, 1995; Krewulak and Vogel, 2008).

Various studies have shown that siderophores are largely produced by bacterial strains associated with plants. This characteristic was the most common trait found in isolates associated with sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.; Ambrosini et al., 2012) and rice (Souza et al., 2013). Notably, in rice roots, isolates belonging to genera Enterobacter and Burkholderia produced the highest levels of siderophores (Souza et al., 2013, 2014). Costa et al. (2014) simultaneously analyzed the PGPB datasets from seven independent studies that employed similar methodologies for bioprospection and observed that 64% of all isolates and 100% of all bacterial genera presented siderophore-producing strains. The bacterial genera Burkholderia, Enterobacter and Grimontella presented strains with high siderophore production, while the genera Klebsiella, Stenotrophomonas, Rhizobium, Herbaspirillum and Citrobacter presented strains with low siderophore production.

The excretion of siderophores by bacteria might stimulate plant growth, thereby improving nutrition (direct effect) or inhibiting the establishment of phytopathogens (indirect effect) through the sequestration of Fe from the environment. Unlike microbial pathogens, plants are not affected by bacterial-mediated Fe depletion, and some plants can even capture and utilize Fe3+-siderophore bacterial complexes (Dimkpa et al., 2009b). The role of endophytic siderophore-producing bacteria has been rarely studied; however, the ability to produce siderophores confers competitive advantages to endophytic bacteria for the colonization of plant tissues and the exclusion of other microorganisms from the same ecological niche (Loaces et al., 2011). These authors observed that the community of endophytic siderophore-producing bacteria associated to rice roots is richer than those from the soil at the tillering and grain-filling stages. Endophytic bacterial strains belonging to genus Burkholderia showed preferential localization inside rice plants, and their role may be relevant to prevent the infection of young plants by Sclerotium oryzae and Rhizoctonia oryzae.

In maize, endophytic strains belonging to genus Bacillus show different plant growth-promoting characteristics, such as siderophore production, and these effects were the most efficient against the growth of Fusarium verticillioides, Colletotrichum graminicola, Bipolaris maydis, and Cercospora zea-maydis fungi (Szilagyi-Zecchin et al., 2014). Siderophores produced by A. brasilense (REC2, REC3) showed in vitro antifungal activity against Colletotrichum acutatum (the causal agent of anthracnose). Also, a reduction of disease symptoms was observed in strawberry (Fragaria vesca) plants previously inoculated with A. brasilense (Tortora et al., 2011).

ACC deaminase activity

Ethylene is an endogenously produced gaseous phytohormone that acts at low concentrations, participating in the regulation of all processes of plant growth, development and senescence (Shaharoona et al., 2006; Saleem et al., 2007). In addition to acting as a plant growth regulator, ethylene has also been identified as a stress phytohormone. Under abiotic and biotic stresses (including pathogen damage, flooding, drought, salt, and organic and inorganic contaminants), endogenous ethylene production is substantially accelerated and adversely affects the growth of the roots and thus the growth of the plant as a whole.

A number of mechanisms have been investigated aiming to reduce the levels of ethylene in plants. One of these mechanisms involves the activity of the bacterial enzyme 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase (Glick, 2005; Jalili et al., 2009; Farajzadeh et al., 2012). ACC deaminase regulates the production of plant ethylene by metabolizing ACC (the immediate precursor of ethylene biosynthesis in higher plants) into α-ketobutyric acid and ammonia (Arshad et al., 2007; Saleem et al., 2007). A significant amount of plant ACC might be excreted from the plant roots and subsequently taken up by soil microorganisms and hydrolyzed by the enzyme ACC deaminase, thus decreasing the amount of ACC in the environment. When associated with plant roots, soil microbial communities with ACC deaminase activity might have a better growth than other free microorganisms, as these organisms use ACC as a source of nitrogen (Glick, 2005).

Bacterial ACC deaminase activity can be conceptually divided into two groups, based on high or low enzymatic activity (Glick, 2005). High ACC deaminase-expressing microorganisms nonspecifically bind to a variety of plant surfaces, and these microbes include rhizosphere and phyllosphere microorganisms and endophytes. However, low ACC deaminase-expressing microorganisms only bind to specific plants or are only present in certain tissues, and although these microbes do not lower the overall level of ethylene produced by the plant, they might prevent a localized increase in ethylene levels. Low ACC deaminase-expressing microorganisms include most, if not all, rhizobia species (Glick, 2005). Shaharoona et al. (2006) demonstrated that the co-inoculation of mung bean (Vigna radiate L.) with Bradyrhizobium and one bacterial strain presenting ACC deaminase activity enhanced nodulation as compared to inoculation with Bradyrhizobium alone, suggesting that this approach might be effective to achieve legume nodulation.

Onofre-Lemus et al. (2009) observed that ACC deaminase activity is a widespread feature in species belonging to genus Burkholderia. These authors identified 18 species of this genus exhibiting this activity; among these bacteria, B. unamae was able to endophytically colonize tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). In addition, tomato plants inoculated with the wild-type B. unamae strain presented better growth than those inoculated with a mutant strain deficient for ACC deaminase activity (Onofre-Lemus et al., 2009). In another study, a mutation in the ACC deaminase pathway altered the physiology of the endophytic B. phytofirmans PsJN2 strain, including the loss of ACC deaminase activity, an increase in IAA synthesis, a decrease in the production of siderophores and the loss of the ability to promote the growth of canola roots (Brassica napus L.; Sun et al., 2009).

Plant growth and productivity is negatively affected by abiotic stresses. Bal et al. (2013) demonstrated the effectiveness of bacteria exhibiting ACC deaminase activity, such as Alcaligenes sp., Bacillus sp., and Ochrobactrum sp., in inducing salt tolerance and consequently improving the growth of rice plants under salt stress conditions. Arshad et al. (2008) obtained similar results, demonstrating that a strain of Pseudomonas spp. with ACC deaminase activity partially eliminated the effect of drought stress on the growth of peas (Pisum sativum L.). Similarly, tomato plants pretreated with the endophytic bacteria P. fluorescens and P. migulae displaying ACC deaminase activity were healthier and showed better growth under high salinity stress compared with plants pretreated with an ACC deaminase-deficient mutant or without bacterial treatment (Ali et al., 2014). Moreover, the selection of endophytes with ACC deaminase activity could also be a useful approach for developing a successful phytoremediation strategy, given the potential of these bacteria to reduce plant stress (Glick, 2010).

Phosphate solubilization

Phosphorus (P) is an essential nutrient for plants, participating as a structural component of nucleic acids, phospholipids and adenosine triphosphate (ATP), as a key element of metabolic and biochemical pathways, important particularly for BNF and photosynthesis (Khan et al., 2009; Richardson and Simpson, 2011). Plants absorb P in two soluble forms: the monobasic (H2PO4 −) and the dibasic (HPO4 2−) (Glass, 1989). However, a large proportion of P is present in insoluble forms and is consequently not available for plant nutrition. Low levels of P reflect the high reactivity of phosphate with other soluble components (Khan et al., 2009), such as aluminum in acid soils (pH < 5) and calcium in alkaline soils (pH > 7) (Holford, 1997; McLaughlin et al., 2011). Organic (incorporated into biomass or soil organic matter) and inorganic compounds, primarily in the form of insoluble mineral complexes, are major sources of available P in the soil (Rodríguez et al., 2006; Richardson and Simpson, 2011). Therefore, the availability of P depends on the solubility of this element, which could be influenced by the activity of plant roots and microorganisms in the soil. Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria and fungi constitute approximately 1-50% and 0.1-0.5%, respectively, of the total population of cultivable microorganisms in the soil (Chabot et al., 1993; Khan et al., 2009).

Among the different sources of P in the soil (as previously mentioned), the solubilization of inorganic phosphates has been the main focus of research studies. Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria solubilize inorganic soil phosphates, such as Ca3(PO4)2, FePO4, and AlPO4, through the production of organic acids, siderophores, and hydroxyl ions (Jones, 1998; Chen et al., 2006; Rodríguez et al., 2006, Sharma et al., 2013). Some bacteria only solubilize calcium phosphate, while other microorganisms are capable of solubilizing other forms of inorganic phosphates at different intensities. Bacterial isolates belonging to genera Enterobacter, Pantoea and Klebsiella solubilize Ca3(PO4)2 to a greater extent than FePO4 and AlPO4 (Chung et al., 2005). The production of organic acids, particularly gluconic and carboxylic, is one of the well-studied mechanisms utilized by microorganisms to solubilize inorganic phosphates (Rodriguez and Fraga, 1999).

Several phosphate-solubilizing bacteria have been isolated from the roots and rhizospheric soil of various plants (Ambrosini et al., 2012; Farina et al., 2012; Costa et al., 2013; Souza et al., 2013, 2014; Granada et al., 2013). Among the 336 strains associated with rice plants, Souza et al. (2013) identified 101 isolates belonging to the genera Burkholderia, Cedecea, Cronobacter, Enterobacter, Pantoea and Pseudomonas which were able to solubilize tricalcium phosphate [Ca3(PO4)2]. Ambrosini et al. (2012) demonstrated that Burkholderia strains associated with sunflower plants were predominant in Ca3(PO4)2 solubilization. Chen et al. (2006) had previously reported several phosphate-solubilizing bacteria strains belonging to the genera Bacillus, Rhodococcus, Arthrobacter, Serratia, Chryseobacterium, Gordonia, Phyllobacterium and Delftia. These authors also identified various types of organic acids produced by bacterial strains, such as the citric, gluconic, lactic, succinic and propionic acids.

Qin et al. (2011) suggested that the ability of rhizobia to solubilize inorganic phosphate is associated with rhizosphere acidification. Moreover, the inoculation with Rhizobium enhanced P acquisition by soybean plants, particularly where Ca3(PO4)2 was the primary P source. The inoculation of rice with the phosphate-solubilizing diazotrophic endophytes Herbaspirillum and Burkholderia increased grain yield and nutrient uptake in plants cultivated in soil with Ca3(PO4)2 and 15N-labeled fertilizer, suggesting that the selection and use of P-solubilizing diazotrophic bacteria is an effective strategy for the promotion of P solubilization (Estrada et al., 2013).

Several studies have reported the isolation of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria from soils or rhizospheres. Confirming that endophytes are important for phosphate solubilization, Chen et al. (2014) observed that the endophyte Pantoea dispersa, isolated from the roots of cassava (Manihot esculenta C.), effectively dissolved Ca3(PO4)2, FePO4, and AlPO4, producing salicylate, benzene-acetic and other organic acids. Moreover, the inoculation of P. dispersa in soil enhanced the concentration of soluble P in a microbial population, increasing the soil microbial diversity, which suggests that an endophyte could adapt to the soil environment and promote the release of P.

Soil also contains a wide range of organic substrates which can be a source of phosphorus for plant growth. Organic P forms, particularly phytates, are predominant in most soils (10-50% of total P) and mineralized by phytases (myo-inositol hexakisphosphate phosphohydrolases) (Rodríguez et al., 2006; Richardson and Simpson, 2011). Bacteria with phytase activity have been isolated from rhizosphere and proposed as PGPB to be used in soils with high content of organic P. Bacterial isolates identified as Advenella are positive for phytase production, and increased the P content and growth of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) (Singh et al., 2014). In another study, Kumar et al. (2013) reported phytase-producing bacteria belonging to genera Tetrathiobacter and Bacillus which also promoted the growth of Indian mustard and significantly increased the P content. Idriss et al. (2002) reported that extracellular phytase from B. amyloliquefaciens FZB45 promoted the growth of maize seedlings. The production of phytase has been characterized in other rhizosphere bacteria, as for example, Bacillus sp., Cellulosimicrobium sp., Acetobacter sp., Klebsiella terrigena, Pseudomonas sp., Paenibacillus sp., and Enterobacter sp. (Yoon et al., 1996; Kerovuo et al., 1998; Idriss et al., 2002; Gulati et al., 2007; Acuña et al., 2011; Jorquera et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2014). Moreover, bacteria with both activities, production of organic acids to solubilize inorganic P and production of phytase to mineralize phytate, have been isolated from the rhizospheres of different plants, such as perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.), white clover (Trifolium repens L.), wheat, oat (Avena sativa L.) and yellow lupin (Lupinus luteus L.) (Jorquera et al., 2008).

Inoculants Can Reduce Chemical Fertilization

The demand for chemical fertilizers in agriculture has historically been influenced by interrelated factors such as population growth worldwide, economic growth, agricultural production, among others (Morel et al., 2012). Interest in the use of inoculants containing PGPB that promote plant growth and yield has increased because nitrogen fertilizers are expensive and can damage the environment through water contamination with nitrates, acidification of soils and greenhouse-gas emissions (Adesemoye et al., 2009; Hungria et al., 2013). Plant-microorganism associations have long been studied, but their exploitation in agriculture for partially or fully replacing nitrogen fertilizers is still low (Hungria et al., 2013). Moreover, plants can only use a small amount of phosphate from chemical sources, because 75-90% of the added P is precipitated through metal-cation complexes and rapidly becomes fixed in soils (Sharma et al., 2013). Approximately 42 million tons of nitrogenous fertilizers are applied annually on a global scale for the production of the three major crop cereals: wheat, rice, and maize. Annually, 8 × 1010 kg of NH3 are produced by nitrogenous fertilizer industries, while 2.5 × 1011 kg of NH3 are fixed through BNF (Cheng, 2008). The nitrogen provided by BNF is less prone to leaching, volatilization and denitrification, as this chemical is used in situ and is therefore considered an important biological process that contributes to sustainable agriculture (Dixon and Kahn, 2004).

The management of bacteria, soil and plant interactions has emerged as a powerful tool in view of the biotechnological potential of these interactions, evidenced by increased crop productivity, reduction of production costs by reducing the volume of fertilizers applied and a better conservation of environmental resources. Moreover, inoculants are composed of beneficial bacteria that can help the plant meet its demands for nutrients. As previously discussed, these bacteria increase plant growth, accelerate seed germination, improve seedling emergence in response to external stress factors, protect plants from disease, and promote root growth using different strategies (Table 1). Whether gram-negative or gram-positive, these bacteria require isolation in culture media and analysis of various genotypic and phenotypic aspects, as well as analysis regarding their beneficial interaction with the host plant in experimental and natural conditions.

Table 1. Examples of PGPB used as inoculants or bacterial culture of different plant species in soil experiments.

| Plant | Experimental conditions | Microorganism (s) | Main PGP-traits3 | Main results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chickpea1 | Field: liquid culture applied to seed | Pseudomonas jessenii PS06, Mesorhizobium ciceri C-2/2 | N2-fixing (C-2/2), P-solubilizing (PS06) | Plants inoculated with C-2/2, in single or dual inoculation, produced higher nodule fresh weight, nodule number and shoot N content, while PS06 had no significant effect on plant growth. However, the co-inoculation ranked highest in seed yield and nodule fresh weight. | Valverde et al. (2006) |

| Pot and field: liquid culture applied to seed | Rhizobium spp., B. subtilis OSU-142, Bacillus megaterium M-3 | N2-fixing (Rhizobium, OSU-142), biocontrol activity (OSU-142, M-3), P-solubilizing (M-3) | In the field, all the combined treatments containing Rhizobium were better for nodulation than the use of Rhizobium alone. Nodulation by native Rhizobium population was increased in single and dual inoculations with OSU-142 and M-3. | Elkoca et al. (2008) | |

| Maize | Pot: liquid culture applied to seed or soil | Burkholderia ambifaria MCI 7 | Siderophore, antifungal activity | The inoculation method influenced the plant growth: seed-applied liquid culture promoted increase on shoot fresh weight as the control, while soil-applied liquid culture reduced plant growth markedly. | Ciccillo et al. (2002) |

| Pot: liquid culture applied to seed | Pseudomonas alcaligenes PsA15, Bacillus polymyxa BcP26, Mycobacterium phlei MbP18 | N2-fixing, antifungal activity (BcP26 and MbP18), IAA (PsA15 and MbP18) | Bacterial inoculation had a much better stimulatory effect on plant growth and NPK content in nutrient-deficient soil than in nutrient-rich soil, where the bacterial inoculants stimulated only root growth and N, K uptake of the roots. | Egamberdiyeva (2007) | |

| Pot and field: liquid inoculant applied to seed | A. brasilense Ab-V5 | N2-fixing, IAA | In pot trials with clay soil, plant growth was increased when Ab-V5 was applied at full dose. In sandy soil, nutrients and Ab-V5 were needed for a significant increase in the maize response. In the field, the grain production was increased when Ab-V5 and N were added, compared to N fertilization alone. | Ferreira et al. (2013) | |

| Pea | Field: peat powder, granular, and liquid inoculant applied to seed or soil | Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae | N2-fixing | The effects of inoculant formulation on nodule number, N accumulation and N2-fixation were: granular peat powder liquid = uninoculated. Soil-applied inoculant improved N nutrition of field pea compared to seed-applied inoculation, with or without applied urea-N. | Clayton et al. (2004) |

| Pot: liquid culture applied to seed | P. fluorescens ACC-5 (biotype G) and ACC-14, P. putida Q-7 (biotype A) | ACC-deaminase | Rhizobacteria containing ACC-deaminase significantly decreased the “drought stress-imposed effects”, although with variable efficacy at different moisture levels. Strain ACC-5 greatly improved the water use efficiency at lowest soil moisture level. | Zahir et al. (2008) | |

| Peanut2 | Pot and field: liquid culture applied to seed | P. fluorescens PGPR1, PGPR2, and PGPR4 | ACC-deaminase, IAA, siderophore, antifungal activity | Pod yield and NP contents in soil, shoot and kernel were significantly enhanced in treatments inoculated in pots, during rainy and post-rainy seasons. The PGPRs also significantly enhanced pod yield, haulm yield and nodule dry weight compared to controls, in 3 years of field trials. | Dey et al. (2004) |

| Rice | Field: peat inoculant applied to soil and seedling | Pseudomonas spp., B. amyloliquefaciens, B. subtilis,soil yeast | Not described | Inoculation significantly increased grain and straw yields and total N uptake, as well as grain quality in terms of N percentage. Inoculation was able to save 43 kg N ha−1, with an additional rice yield of 270 kg ha−1 in two consecutive rainy seasons at the experimental site. | Cong et al. (2009) |

| Pot and field: liquid culture applied to seedling | Azospirillum sp. B510 | N2-fixing, IAA | The field experiment indicated that inoculation with B510 increases tiller number, resulting in an increase in seed yield at commercial levels when compared with uninoculated plants. | Isawa et al. (2010) | |

| Field: liquid culture applied to seedling | Azospirillum sp. B510 | N2-fixing, IAA | Growth in terms of tiller numbers and shoot length was significantly increased by inoculation. The application of Azospirillum sp. B510 not only enhanced rice growth, but also affected minor rice-associated bacteria. | Bao et al. (2013) | |

| Soybean | Field: granular and peat inoculant applied to seed and in-furrow | Bacillus cereus UW85 (granular) and B. japonicum (peat) | Not described | The inoculation with UW85 resulted in stimulations in shoot dry weight, increased seed yield and seed N content, but the effect was site-specific. The stimulation in growth and N parameters by UW85 treatment was proportionally greater in the absence of B. japonicum inoculation than in the presence of the rhizobial inoculant. | Bullied et al. (2002) |

| Field: liquid inoculant applied to seed and in-furrow | B. japonicum SEMIA 5079 and SEMIA 5080, A. brasilense Ab-V5 and Ab-V6 | N2-fixing, IAA | Inoculation of seeds with rhizobia increased soybean yield by 8.4 %, and co-inoculation with A. brasilense in-furrow by an average 16.1 %. Seed co-inoculation with both microorganisms resulted in a mean yield increase of 14.1 % in soybean compared to the uninoculated control. | Hungria et al. (2013) | |

| Pot: liquid culture applied to seed | B. amyloliquefaciens sks_bnj_1 | Siderophore, IAA, ACC-deaminase, antifungal activity, phytases | Inoculation significantly increased rhizosphere soil properties (enzyme activities, IAA production, microbial respiration, microbial biomass-C), and nutrient content in straw and seeds of soybean compared to uninoculated control. | Sharma et al. (2013) | |

| Sugarcane | Pot and field: liquid culture applied to seedlings | B. vietnamiensis MG43, G. diazotrophicus LMG7603, H. seropedicae LMG6513 | N2-fixing | Biomass increase due to MG43 inoculation reached 20% in the field. The inoculation of three strains was less effective than inoculation by a single MG43 suspension. | Govindarajan et al. (2006) |

| Field: liquid culture applied to stem cuttings | G. diazotrophicus VI27 | N2-fixing, siderophore, IAA, P-solubilizing | The strain showed a significant increase in the number of sets germinated, in the amount of soluble solids, and in the yield of sugarcane juice compared to control. | Beneduzi et al. (2013) | |

| Wheat | Field: liquid inoculant applied to seed | A. brasilense INTA Az-39 | N2-fixing, IAA | The inoculated crops exhibited more vigorous vegetative growth, with both greater shoot and root dry matter accumulation. Positive responses were found in about 70% of the experimental sites (total: 297 sites), independently of fertilization and other crop and soil management practices. | Díaz-Zorita and Fernández-Canigia (2009) |

| Pot: liquid culture applied to soil | B. subtilis SU47, Arthrobacter sp. SU18 | IAA, P-solubilizing | Sodium content was reduced under co-inoculation conditions but not after single inoculation with either strain or in the control. Plants grown under different salinity regimes and PGPR co-inoculation showed an increase in dry biomass, total soluble sugars and proline content, and reduced activity of antioxidant enzymes. | Upadhyay et al. (2012) | |

| Wheat and maize | Field: peat and liquid inoculant applied to seed | A. brasilense Ab-V5 and Ab-V6 | N2-fixing, IAA | Inoculants increased maize and wheat yields at low N fertilizer starter at sowing by 27% and 31%, respectively. A liquid inoculant containing a combination of the strains proved to be as effective as peat inoculant carrying the same strains, in both maize and wheat. | Hungria et al. (2010) |

Cicer arietinum L.

Arachis hypogaea L.

When the characteristic is not displayed by all strains, those that present it are shown in parenthesis.

Rhizobia species are well investigated because of their symbiotic relationship with leguminous plants and their agronomical application as inoculants in the cultivation of economic crops (Alves et al., 2004; Torres et al., 2012). The soybean-Bradyrhizobium association is a good example of the efficiency of BNF, and B. elkanii and B. japonicum are species commonly used to inoculate this leguminous plant. In this system, the BNF is so efficient that attempts to increase grain yields by adding nitrogenous fertilizers are not successful in plants effectively inoculated with the recommended Bradyrhizobium strains (Alves et al., 2004). In Brazil, where approximately 70% of the nitrogenous fertilizers are imported, the costs of mineral N utilization in agriculture are high, and inoculants are a more cost-effective alternative, particularly for soybean crops. It is estimated that, in this culture alone, Brazil saves approximately US$ 7 billion per year thanks to the benefits of BNF (Hungria et al., 2013).

In the last few decades, a large array of bacteria associated with non-leguminous plants, including Azospirillum species, have demonstrated plant growth-promoting properties (Okon and Labandrera-Gonzalez, 1994; Garcia de Salamone et al., 1996; Bashan et al., 2004; Cassán and Garcia de Salamone, 2008; Hungria et al., 2010). Azospirillum might promote the growth, yield and nutrient uptake of different plant species of agronomic importance, particularly wheat and maize (Hungria et al., 2010). Inoculants containing Azospirillum have been tested under field conditions in Argentina, with positive results regarding plant growth and/or grain yield (Cassán and Garcia de Salamone, 2008). In Brazil, field experiments designed to evaluate the performance of A. brasilense strains isolated from maize plants showed effectiveness in both maize and wheat. These results were grounds for the authorization of the first strains of inoculants to be produced and commercially used in wheat and maize in this country. According to the authors (Hungria et al., 2010), the partial (50%) replacement of the nitrogenous fertilizer required for these crops in association with Azospirillum sp. inoculation would save an estimated US$ 1.2 billion per year, suggesting that the use of inoculants could reduce the use of chemical fertilizers worldwide.

Inoculation with a consortium of several bacterial strains could be an alternative to inoculation with individual strains, likely reflecting the different mechanisms used by each strain in the consortium. The co-inoculation of soybean and common bean (P. vulgaris L.) with rhizobia and A. brasilense inoculants showed good results for improving sustainability (Hungria et al., 2013). In field trials, the co-inoculation of soybean with B. japonicum and A. brasilense species resulted in outstanding increases in grain yield and improved nodulation compared with the non-inoculated control. For common bean, co-inoculation with Rhizobium tropici and A. brasilense species resulted in an impressive increase in grain yield, varying from 8.3% when R. tropici was inoculated alone to 19.6% when the two bacterial species were used. Domenech et al. (2006) showed that the inoculation of tomato and pepper with a product based on Bacillus subtilis GB03 (a growth-promoting agent), B. amyloliquefaciens IN937a (endophytic bacteria, systemic resistance inducer) and chitosan, combined with different bacterial strains such as P. fluorescens, provided better biocontrol against Fusarium wilt and Rhizoctonia damping-off as compared to the use of the product alone.

Processes Involved in the Efficiency of Inoculation

Exudation by plant roots

Plant roots respond to environmental conditions through the secretion of a wide range of compounds, according to nutritional status and soil conditions (Cai et al., 2012; Carvalhais et al., 2013). This action interferes with the plant-bacteria interaction and is an important factor contributing to the efficiency of the inoculant (Cai et al., 2009, 2012; Carvalhais et al., 2013). Root exudation includes the secretion of ions, free oxygen and water, enzymes, mucilage, and a diverse array of C-containing primary and secondary metabolites (Bais et al., 2006). The roots of plants excrete 10-44% of photosynthetically fixed C, which serves as energy source, signaling molecules or antimicrobials for soil microorganisms (Guttman et al., 2014). The root exudation varies with plant age and genotype, and consequently specific microorganisms respond and interact with different host plants (Bergsma-Vlami et al., 2005; Aira et al., 2010; Ramachandran et al., 2011). Thus, inoculants are generally destined to the one specific plant from which the bacterium was isolated.

The well-studied flavonoids also vary with plant age and physiological state when exuded from legume rhizospheres, and induce nodD gene expression in rhizobial strains. NodD is a transcriptional activator of bacterial genes involved in the infection and nodule formation during the establishment of legume-rhizobia symbioses (Long, 2001). Similarly to flavonoids, several compounds secreted by roots modulate the relationships between plants and PGPB (Badri et al., 2009). Bacillus subtilis FB17, for instance, is attracted by L-malic acid, secreted by the roots of Arabidopsis thaliana infected with the foliar pathogen P. syringae pv tomato (Pst DC3000; Rudrappa et al., 2008). Profiles of secreted secondary metabolites, such as phenolic compounds, flavonoids and hydroxycinnamic derivatives, were different in rice cultivars (Nipponbare and Cigalon), according to inoculation with Azospirillum 4B and B510 strains. Interestingly, strains 4B and B510 preferentially increased the growth of the cultivar from which they were isolated; however, both strains effectively colonized either at the rhizoplane (4B and B510) or inside roots (B510) (Chamam et al., 2013).

Some molecules exudated from roots might act as antimicrobial agents against one organism and as stimuli for the establishment of beneficial interactions with regard to other organisms. For example, canavanine, a non-protein amino acid analog to arginine, secreted at high concentrations by many varieties of legume seeds, acts as an antimetabolite in many biological systems and also stimulates the adherence of rhizobia that detoxify this compound (Cai et al., 2009). In the Leguminosae family, canavanine is a major N storage compound in the seeds of many plants, and constitutes up to 13% of the dry weight of seeds (Rosenthal, 1972). Benzoxazinoids (BXs) are secondary metabolites synthesized by Poaceae during early plant growth stages. These molecules are effective in plant defense and allelopathy (Nicol et al., 1992; Zhang et al., 2000; Frey et al., 2009; Neal et al., 2012). However, qualitative and quantitative modifications of BXs production in maize were differentially induced according to inoculation with different Azospirillum strains (Walker et al., 2011a, b).

The quantitative and qualitative changes in the composition of the exudates result from the activation of biochemical defense systems through elicitors mimicking stresses in plants. Biotic and abiotic elicitors stimulate defense mechanisms in plant cells and greatly increase the diversity and amount of exudates (Cai et al., 2012). Several studies have reported that endophytic PGPB induce stress and defense responses, causing changes in plant metabolites that lead to the fine control of bacterial populations inside plant tissues (Miché et al., 2006; Chamam et al., 2013; Straub et al., 2013). Jasmonate is an important plant-signaling molecule that mediates biotic and abiotic stress responses and aspects of growth and development (Wasternack, 2007). Rocha (2007) showed that the jasmonate response is initiated prior to the establishment of an effective association. Following the inoculation of Miscanthus sinensis with H. frisingense GSF30T, transcriptome and proteome data showed the rapid and strong up-regulation of jasmonate-related genes in plants, and this effect was suppressed after the establishment of an association with bacteria (Straub et al., 2013).

Bacterial root colonization

Rhizosphere competence reflects variation in the ability of a PGPB to colonize plant roots during the transition from free-living to root-associated lifestyles. The attachment and colonization of roots are modulated through PGPB abilities involved in important processes for survival, growth, and function in soil (Cornforth and Foster, 2013). Associative and endophytic PGPB respond to plant exudates through the modulation of the expression of several genes, such as those associated with exopolysaccharide (EPS) biosynthesis and biofilm formation (Rudrappa et al., 2008; Meneses et al., 2011; Beauregard et al., 2013). Biofilms are surface-adherent microbial populations typically embedded within a self-produced matrix material (Fuqua and Greenberg, 2002). As previously mentioned, B. subtilis is attracted by L-malic acid secreted by A. thaliana. Moreover, bacterial biofilm formation is selectively triggered through L-malic acid, in a process dependent on the same gene matrix required for in vitro biofilm formation (Rudrappa et al., 2008; Beauregard et al., 2013). EPS biosynthesis is also required for biofilm formation and plant colonization by the endophyte G. diazotrophicus. A functional mutant of G. diazotrophicus PAL5 for EPS production did not attach to the rice root surface or exhibit endophytic colonization (Meneses et al., 2011).

Cell-cell communication via quorum sensing (QS) regulates root colonization and biocontrol (Danhorn and Fuqua, 2007). Quorum sensing involves intercellular signaling mechanisms that coordinate bacterial behavior, host colonization and stress survival to monitor population density (Danhorn and Fuqua, 2007; Schenk et al., 2012; He and Bauer, 2014). Plant-associated bacteria frequently employ this signaling mechanism to modulate and coordinate interactions with plants, including acylated homoserine lactones (AHLs) among proteobacteria and oligopeptides among gram-positive microbes (Danhorn and Fuqua, 2007). The endophytic G. diazotrophicus PAL5 strain colonizes a broad range of host plants, presenting QS comprising luxR and luxI homolog gene products and producing eight molecules of the AHL family (Bertini et al., 2014). The levels of QS were modified according to glucose concentration, the presence of other C sources and saline stress conditions.

Stress-induced bacterial genes are also associated with plant-bacterial interactions. The bacterial enzymes superoxide dismutase and glutathione reductase were crucial for the endophytic colonization of rice roots by G. diazotrophicus PAL5 (Alquéres et al., 2013). Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 genes involved in chemotaxis and motility were induced through exudates from P-deficient maize plants, whereas the exudates from N-deficient plants triggered a general bacterial stress response (Carvalhais et al., 2013). The global gene expression of A. lipoferum 4B cells during interactions with different rice cultivars (Nipponbare and Cigalon) involved genes associated with reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxification, multidrug efflux, and complex regulatory networks (Drogue et al., 2014). The cultivar-specific expression profiles of PGPB suggested host-specific adaptation (Drogue et al., 2014).

Moreover, microbial competition was closely associated with the root colonization efficiency of PGPB, as the exudation of different compounds attracts a great number of different microbial populations. The deposition of nutrients in the plant rhizosphere (rhizodeposition) supports higher microbial growth than the surrounding soil, a phenomenon referred to as the “rhizosphere effect” (Rovira, 1965; Dunfield and Germida, 2003; Mougel et al., 2006). This intense molecular communication surrounding the roots provides a broad range of microbe-microbe interactions, making this environment highly competitive among soil bacteria. Microbial competition and activities include, for example, motility (Capdevila et al., 2004; de Weert et al., 2002), attachment (Buell and Anderson, 1992; Rodriguez-Navarro et al., 2007), growth (Browne et al., 2009; Miller et al., 2010), stress resistance (Espinosa-Urgel et al., 2000; Martinez et al., 2009), secondary metabolite production (Abbas et al., 2002; Haas and Defago, 2005), and quorum sensing (Edwards et al., 2009; Ramachandran et al., 2011).

Soil health

Soil is a heterogeneous mixture of different organisms and organic and mineral substances present in three phases: solid, liquid, and gaseous (Kabata-Pendias, 2004). The physical forces and natural grouping of particles result in the formation of soil aggregates of different sizes, arrangements and stabilities, which are the basic units of soil structure (Lynch and Bragg, 1985). Soil aggregation is influenced by several factors, such as soil mineralogy, cycles of wetting and drying, the presence of iron and aluminum oxides as a function of soil pH range, and clay and organic material contents (Lynch and Bragg, 1985; Cammeraat and Imeson, 1998; Castro Filho et al., 2002; Majumder and Kuzyakov, 2010; Vogel et al., 2014). Plant roots directly contribute to the stability of soil aggregates through the inherent abundance of these structures in organic matter and the production of exudates stimulating microbial activity, and indirectly by the production of EPS (Leigh and Coplin, 1992; Alami et al., 2000; Schmidt et al., 2011).

The fine spatial heterogeneity of soils results in a complex mosaic of gradients selecting for or against bacterial growth (Vos et al., 2013). The microbial biomass decreases with soil depth, and changes in the community composition reflect substrate specialization (Schmidt et al., 2011). The distribution of micro (< 250 μm) and macro (> 250 μm)-aggregates provides microhabitats differentially assembled in terms of temperature, aeration, water retention and movement (Dinel et al., 1992; Zhang, 1994; Denef et al., 2004; Schmidt et al., 2011). Soil aggregates of different pore sizes influence C sequestration and the availability of nutrients (Zhang et al., 2013), and low pore connectivity due to low water potential increases the diversity of bacterial communities in the soil (Carson et al., 2010; Ruamps et al., 2011). Moreover, the moisture content, pore size and habitat connectivity differently impact the expansion of motile rod-shaped and filamentous bacterium types (Wolf et al., 2013).

Soil stability results from a combination of biotic and abiotic characteristics, and the microbial communities could provide a quantitative measure of soil health, as these bacteria determine ecosystem functioning according to biogeochemical processes (Griffiths and Philippot, 2012). Soil health defines the capacity of soil to function as a vital living system, within ecosystem and land-use boundaries, to sustain plant and animal productivity, maintain or enhance water and air quality, and promote plant and animal health (Doran and Zeiss, 2000). The factors controlling broad-range soil health comprise chemical, physical, and biological features, such as soil type, climate, cropping patterns, use of pesticides and fertilizers, availability of C substrates and nutrients, toxic material concentrations, and the presence or absence of specific assemblages and types of organisms (Doran and Zeiss, 2000; Young and Ritz, 1999; Kibblewhite et al., 2008).

The sustainable management of soils requires soil monitoring, including biological indicators such as microbial communities, which provide many potentially interesting indicators for environmental monitoring in response to a range of stresses or disturbances (Pulleman et al., 2012). Community stability is a functional property that focuses on community dynamics in response to perturbation: the return to a state of equilibrium following perturbation is the ability to resist to changes, which is called resistance; the rate of return to a state of equilibrium following perturbation is called resilience (Robinson et al., 2010). Soil functional resilience is governed by the effects of the physicochemical structure on microbial community composition and physiology (Griffiths et al., 2008). Microbial catabolic diversity is reduced through intensive land-use, which may have implications for the resistance of the soils to stress or disturbance (Degens et al., 2001; Ding et al., 2013).

Modern land-use practices highly influence the factors controlling soil health because, while these techniques increase the short-term supply of material goods, over time these practices might undermine many ecosystem services on regional and global scales (Foley et al., 2005). Soil disturbances operate at various spatial and temporal scales and mediate soil spatial heterogeneity. For instance, such disturbances may reduce the biomass of dominant organisms or provoke alterations in the physical structure of the soil substrate (Ettema and Wardle, 2002). Cultivation intensity reduces C content and changes the distribution and stability of soil aggregates, leading to a loss of C-rich macroaggregates and an increase of C-depleted microaggregates in soils (Six et al., 2000). Moreover, soil aggregation is a major ecosystem process directly impacted, via intensified land-use, by soil disturbances, or indirectly through impacts on biotic and abiotic factors that affect soil aggregates (Barto et al., 2010).

The physical disruption spectrum induced by tillage presents various degrees of soil disturbance and associations between no-tillage or minimum tillage and the ‘beneficial’ effects on soil microorganisms (Elliott and Coleman, 1988; Derpsch et al., 2014). The primary effect of tillage is the physical disturbance of the soil profile through alterations in the habitat space, water and substrate distribution and the spatial arrangement of pore pathways (Young and Ritz, 1999). Accumulated evidence suggests that conserved tillage systems, including no-tillage and reduced tillage, effectively reverse the disadvantage of conventional tillage in depleting the carbon stock through increases in the abundance and activity of the soil biota (Zhang et al., 2013). Lower microbial biomass in arable land likely reflects soil disturbance through tillage and the tillage-induced changes in soil properties (Cookson et al., 2008).

Disturbances alter the immediate environment, potentially leading to repercussions or direct alterations to this community (Shade et al., 2012). The manipulation of soil structure is one of the principal mechanisms for the regulation of microbial dynamics, at both the small and field scale (Elliott and Coleman, 1988; Derpsch et al., 2014). The microscale impact in crop soil under grassland, tillage, and no-tillage systems resulted in micro-aggregates containing similar bacterial communities, despite the land management practice, whereas strong differences were observed between communities inhabiting macro-aggregates (Constancias et al., 2014). In this same study, tillage decreased the density and diversity of bacteria from 74 to 22% and from 11 to 4%, respectively, and changed taxonomic groups in micro and macro-aggregates. These changes led to the homogenization of bacterial communities, reflecting the increased protection of micro-aggregates.

The combination of crop rotation with legumes, tillage management and soil amendments considerably influences the microbiotic properties of soil. Conventional agriculture systems, according to the FAO definition, use no tillage and have seeds placed at a proper depth in untilled soil, with previous crops or cover crop residues retained on the soil surface. In a no-tillage system, crop residue management plays an equally important role in minimizing and even avoiding soil disturbance (Derpsch et al., 2014). More research will expand our understanding of the combined effects of these alternatives on feedback between soil microbiotic properties and soil organic C accrual (Ghimire et al., 2014). However, the terms “reduced tillage” or “minimum tillage” or other degrees of tillage disturbance have been coined as no-tillage systems, and this term has been revised to “conservation agriculture systems” as a more holistic description (Derpsch et al., 2014). These authors also revised other terms associated with no-tillage systems.

Conclusions

At a global scale, the effects of continuous agricultural practices such as fertilization can cause serious damage to the environment. Inoculation is one of the most important sustainable practices in agriculture, because microorganisms establish associations with plants and promote plant growth by means of several beneficial characteristics. Endophytes are suitable for inoculation, reflecting the ability of these organisms for plant colonization, and several studies have demonstrated the specific and intrinsic communication among bacteria and plant hosts of different species and genotypes.

The combination of different methodologies with these bacteria, such as identification of plant growth-promoting characteristics, the identification of bacterial strains, as well as assays of seed inoculation in laboratory conditions and cultivation experiments in the field, are part of the search for new technologies for agricultural crops. Thus, when this search shows a potential bacterial inoculant, adequate for reintroduction in the environment, many genera such as Azospirillum, Bacillus and Rhizobium may be primary candidates.

Finally, the search for beneficial bacteria is important for the development of new and efficient inoculants for agriculture. Also important are investments in technologies that can contribute to increase the inoculum efficiency and the survival rate of bacteria adherent to the seeds, which are other essential factors for successful inoculation. Thus, the introduction of beneficial bacteria in the soil tends to be less aggressive and cause less impact to the environment than chemical fertilization, which makes it a sustainable agronomic practice and a way of reducing the production costs.

References

- Abbas A, Morrissey JP, Marquez PC, Sheehan MM, Delany IR, O'Gara F. Characterization of interactions between the transcriptional repressor PhlF and its binding site at the phlA promoter in Pseudomonas fluorescens F113. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:3008–3016. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.11.3008-3016.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acuña JJ, Jorquera MA, Martínez OA, Menezes-Blackburn D, Fernández MT, Marschner P, Greiner R, Mora ML. Indole acetic acid and phytase activity produced by rhizosphere bacilli as affected by pH and metals. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2011;11:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Adesemoye AO, Torbert HA, Kloepper JW. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria allow reduced application rates of chemical fertilizers. Microb Ecol. 2009;58:921–929. doi: 10.1007/s00248-009-9531-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aira M, Gómez-Brandón M, Lazcano C, Baath E, Domínguez J. Plant genotype strongly modifies the structure and growth of maize rhizosphere microbial communities. Soil Biol Biochem. 2010;42:2276–2281. [Google Scholar]

- Akbari GA, Arab SM, Alikhani HA, Allahdadi I, Arzanesh MH. Isolation and selection of indigenous Azospirillum spp. and the IAA of superior strains effects on wheat roots. World J Agric Sc. 2007;3:523–529. [Google Scholar]

- Alami Y, Achouak W, Marol C, Heulin T. Rhizosphere soil aggregation and plant growth promotion of sunflowers by an exopolysaccharide-producing Rhizobium sp. strain isolated from sunflower roots. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:3393–3398. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.8.3393-3398.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S, Trevor CC, Glick BR. Amelioration of high salinity stress damage by plant growth-promoting bacterial endophytes that contain ACC deaminase. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2014;80:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alquéres S, Meneses C, Rouws L, Rothballer M, Baldani I, Schmid M, Hartmann A. The bacterial superoxide dismutase and glutathione reductase are crucial for endophytic colonization of rice roots by Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus PAL5. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2013;26:937–945. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-12-12-0286-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves BJR, Boddey RM, Urquiaga S. The success of BNF in soybean in Brazil. Plant Soil. 2004;252:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosini A, Beneduzi A, Stefanski T, Pinheiro FG, Vargas LK, Passaglia LMP. Screening of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria isolated from sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) Plant Soil. 2012;356:245–264. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews SC, Robinson AK, Rodríguez-Quinõnes F. Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:215–237. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00055-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold W, Rump A, Klipp W, Priefer UB, Pühler A. Nucleotide sequence of a 24,206-base-pair DNA fragment carrying the entire nitrogen fixation gene cluster of Klebsiella pneumoniae . J Mol Biol. 1988;203:715–738. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arshad M, Saleem M, Hussain S. Perspectives of bacterial ACC deaminase in phytoremediation. Trends Biotechnol. 2007;25:356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arshad M, Shaharoona B, Mahmood T. Inoculation with Pseudomonas spp. containing ACC-deaminase partially eliminates the effects of drought stress on growth, yield, and ripening of pea (Pisum sativum L.) Pedosphere. 2008;18:611–620. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon CW, Hinton DM. Bacterial endophytes: The endophytic niche, its occupants, and its utility. In: Gnanamanickam SS, editor. Plant-Associated Bacteria. Springer; Netherlands: 2006. pp. 155–194. [Google Scholar]

- Badri DV, Vivanco JM. Regulation and function of root exudates. Plant Cell Environ. 2009;32:666–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bais HP, Weir TL, Perry LG, Gilroy S, Vivanco JM. The role of root exudates in rhizosphere interactions with plants and other organisms. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:233–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldani JI, Caruso L, Baldani VLD, Goi SR, Döbereiner J. Recent advances in BNF with non-legume plants. Soil Biol Biochem. 1997;29:911–922. [Google Scholar]

- Bal HB, Nayak L, Das S, Adhya TK. Isolation of ACC deaminase producing PGPR from rice rhizosphere and evaluating their plant growth promoting activity under salt stress. Plant Soil. 2013;366:93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Bao Z, Sasaki K, Okubo T, Ikeda S, Anda M, Hanzawa E, Kaori K, Tadashi S, Hisayuki M, Minamisawa K. Impact of Azospirillum sp. B510 inoculation on rice-associated bacterial communities in a paddy field. Microbes Environ. 2013;28:487–490. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME13049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barto EK, Alt F, Oelmann Y, Wilcke W, Rillig MC. Contributions of biotic and abiotic factors to soil aggregation across a land use gradient. Soil Biol Biochem. 2010;42:2316–2324. [Google Scholar]

- Bashan Y, Holguin G, De-Bashan LE. Azospirillum-plant relations physiological, molecular, agricultural, and environmental advances (1997-2003) Can J Microbiol. 2004;50:521–577. doi: 10.1139/w04-035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudoin E, Lerner A, Mirza MS, Zemrany HE, Prigent-Combaret C, Jurkevich E, Spaepen S, Vanderleyden J, Nazaret S, Okon Y, et al. Effects of Azospirillum brasilense with genetically modified auxin biosynthesis gene ipdC upon the diversity of the indigenous microbiota of the wheat rhizosphere. Res Microbiol. 2010;161:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauregard PB, Chai Y, Vlamakis H, Losick R, Kolter R. Bacillus subtilis biofilm induction by plant polysaccharides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E1621–E1630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218984110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beneduzi A, Moreira F, Costa PB, Vargas LK, Lisboa BB, Favreto R, Baldani JI, Passaglia LMP. Diversity and plant growth promoting evaluation abilities of bacteria isolated from sugarcane cultivated in the South of Brazil. Appl Soil Ecol. 2013;63:94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Bergsma-Vlami M, Prins ME, Raaijmakers JM. Influence of plant species on population dynamics, genotypic diversity and antibiotic production in the rhizosphere by indigenous Pseudomonas spp. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2005;52:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertalan M, Albano R, de Pádua V, Rouws L, Rojas C, Hemerly A, Teixeira K, Schwab S, Araujo J, Oliveira A, et al. Complete genome sequence of the sugarcane nitrogen-fixing endophyte Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus PAl5. BMC Genomics. 2009;10: doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini EV, Peñalver CGN, Leguina AC, Irazusta VP, De Figueroa LI. Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus PAL5 possesses an active quorum sensing regulatory system. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2014;106:497–506. doi: 10.1007/s10482-014-0218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher Y, Douady CJ, Papke RT, Walsh DA, Boudreau MER, Nesbo CL, Case J, Doolittle WF. Lateral gene transfer and the origins of prokaryotic groups. Annu Rev Genet. 2003;37:283–328. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.050503.084247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullied JW, Buss WTJ, Vessey KJ. Bacillus cereus UW85 inoculation effects on growth, nodulation, and N accumulation in grain legumes: Field studies. Can J Plant Sci. 2002;82:291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Browne P, Rice O, Miller SH, Burke J, Dowling DN, Morrissey JP, O'Gara F. Superior inorganic phosphate solubilization is linked to phylogeny within the Pseudomonas fluorescens complex. Appl Soil Ecol. 2009;43:131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Buell CR, Anderson AJ. Genetic analysis of the aggA locus involved in agglutination and adherence of Pseudomonas putida, a beneficial fluorescent pseudomonad. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1992;5:154–162. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-5-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai T, Cai W, Zhang J, Zheng H, Tsou AM, Xiao L, Zhong Z, Zhu J. Host legume-exuded antimetabolites optimize the symbiotic rhizosphere. Mol Microbiol. 2009;73:507–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z, Kastell A, Knorr D, Smetanska I. Exudation: An expanding technique for continuous production and release of secondary metabolites from plant cell suspension and hairy root cultures. Plant cell reports. 2012;31:461–477. doi: 10.1007/s00299-011-1165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammeraat LH, Imeson AC. Deriving indicators of soil degradation from soil aggregation studies in southeastern Spain and southern France. Geomorphology. 1998;23:307–321. [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila S, Martinez-Granero FM, Sanchez-Contreras M, Rivilla R, Martin M. Analysis of Pseudomonas fluorescens F113 genes implicated in flagellar filament synthesis and their role in competitive root colonization. Microbiology-SGM. 2004;150:3889–3897. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27362-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson JK, Gonzalez-Quiñones V, Murphy DV, Hinz C, Shaw JA, Gleeson DB. Low pore connectivity increases bacterial diversity in soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:3936–3942. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03085-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalhais LC, Dennis PG, Fan B, Fedoseyenko D, Kierul K, Becker A, Von Wiren N, Borriss R. Linking plant nutritional status to plant-microbe interactions. PLoS One. 2013;8: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassán FD, Garcia de Salamone I. Azospirillum sp.: Cell Physiology, Plant Interactions and Agronomic Research in Argentina. Asociación Argentina de Microbiologia; Argentina: 2008. 276 p [Google Scholar]

- Castro C, Filho, Lourenço A, De F Guimarães M, Fonseca ICB. Aggregate stability under different soil management systems in a red latosol in the state of Parana, Brazil. Soil Tillage Res. 2002;65:45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Chabot R, Antoun H, Cescas MP. Stimulation de la croissance du mais et de la laitue romaine par desmicroorganismes dissolvant le phosphore inorganique. Can J Microbiol. 1993;39:941–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chamam A, Sanguin H, Bellvert F, Meiffren G, Comte G, Wisniewski-Dyé F, Bertrand C, Prigent-Combaret C. Plant secondary metabolite profiling evidences strain-dependent effect in the Azospirillum-Oryza sativa association. Phytochemistry. 2013;87:65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Q. Perspectives in biological nitrogen fixation research. J Integr Plant Biol. 2008;50:784–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YP, Rekha PD, Arun AB, Shen FT, Lai WA, Young CC. Phosphate solubilizing bacteria from subtropical soil and their tricalcium phosphate solubilizing abilities. Appl Soil Ecol. 2006;34:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Fan JB, Du L, Xu H, Zhang QY, He YQ. The application of phosphate solubilizing endophyte Pantoea dispersa triggers the microbial community in red acidic soil. Appl Soil Ecol. 2014;84:235–244. [Google Scholar]

- Chung H, Park M, Madhaiyana M, Seshadri S, Song J, Cho H, Sa T. Isolation and characterization of phosphate solubilizing bacteria from the rhizosphere of crop plants of Korea. Soil Biol Biochem. 2005;3:1970–1974. [Google Scholar]

- Ciccillo F, Fiore A, Bevivino A, Dalmastri C, Tabacchioni S, Chiarini L. Effects of two different application methods of Burkholderia ambifaria MCI7 on plant growth and rhizospheric bacterial diversity. Environ Microbiol. 2002;4:238–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton GW, Rice WA, Lupwayi NZ, Johnston AM, Lafond GP, Grant CA, Walley F. Inoculant formulation and fertilizer nitrogen effects on field pea: Nodulation, N2 fixation and nitrogen partitioning. Can J Plant Sci. 2004;84:79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Cong PT, Dung TD, Hien TM, Hien NT, Choudhury AT, Kecskés ML, Kennedy IR. Inoculant plant growth-promoting microorganisms enhance utilisation of urea-N and grain yield of paddy rice in southern Vietnam. Eur J Soil Biol. 2009;45:52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Constancias F, Prévost-Bouré NC, Terrat S, Aussems S, Nowak V, Guillemin JP, Bonnotte A, Biju-Duval L, Navel A, Martins JMF, et al. Microscale evidence for a high decrease of soil bacterial density and diversity by cropping. Agron Sustainable Dev. 2014;34:831–840. [Google Scholar]

- Cookson WR, Murphy DV, Roper MM. Characterizing the relationships between soil organic matter components and microbial function and composition along a tillage disturbance gradient. Soil Biol Biochem. 2008;40:763–777. [Google Scholar]

- Cornforth DM, Foster KR. Competition sensing: The social side of bacterial stress responses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:285–293. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa P, Beneduzi A, Souza R, Schoenfeld R, Vargas LK, Passaglia LMP. The effects of different fertilization conditions on bacterial plant growth promoting traits: Guidelines for directed bacterial prospection and testing. Plant Soil. 2013;368:267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PB, Granada CE, Ambrosini A, Moreira F, Souza R, Passos JFM, Arruda L, Passaglia LMP. A model to explain plant growth promotion traits: A multivariate analysis of 2,211 bacterial isolates. PLoS One. 2014;9: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danhorn T, Fuqua C. Biofilm formation by plant-associated bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:401–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denef K, Six J, Merckx R, Paustian K. Carbon sequestration in microaggregates of no-tillage soils with different clay mineralogy. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 2004;68:1935–1944. [Google Scholar]

- Degens BP, Schipper LA, Sparling GP, Duncan LC. Is the microbial community in a soil with reduced catabolic diversity less resistant to stress or disturbance? Soil Biol Biochem. 2001;33:1143–1153. [Google Scholar]

- Derpsch R, Franzluebbers AJ, Duiker SW, Reicosky DC, Koeller K, Friedrich T, Sturny WG, Sá JCM, Weiss K. Why do we need to standardize no-tillage research? Soil Tillage Res. 2014;137:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dey R, Pal KK, Bhatt DM, Chauhan SM. Growth promotion and yield enhancement of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) by application of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Microbiol Res. 2004;159:371–394. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Weert S, Vermeiren H, Mulders IHM, Kuiper I, Hendrickx N, Bloemberg GV, Vanderleyden J, De Mot R, Lugtenberg BJJ. Flagella-driven chemotaxis towards exudate components is an important trait for tomato root colonization by Pseudomonas fluorescens . Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2002;15:1173–1180. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.11.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Zorita M, Fernández-Canigia MV. Field performance of a liquid formulation of Azospirillum brasilense on dryland wheat productivity. Eur J Soil Biol. 2009;45:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dimkpa C, Weinand T, Asch F. Plant-rhizobacteria interactions alleviate abiotic stress conditions. Plant Cell Environ. 2009a;32:1682–1694. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimkpa CO, Merten D, Svatos A, Büchel G, Kothe E. Siderophores mediate reduced and increased uptake of cadmium by Streptomyces tendae F4 and sunflower (Helianthus annuus), respectively. J Appl Microbiol. 2009b;5:687–1696. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinel H, Levesque PEM, Jambu P, Righi D. Microbial activity and long-chain aliphatics in the formation of stable soil aggregates. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1992;56:1455–1463. [Google Scholar]

- Ding GC, Piceno YM, Heuer H, Weinert N, Dohrmann AB, Carrillo A, Andersen GL, Castellanos T, Tebbe CC, Smalla K. Changes of soil bacterial diversity as a consequence of agricultural land use in a semi-arid ecosystem. PLoS One. 2013;8: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]