Abstract

DNA N6-adenine methylation (6mA) in prokaryotes functions primarily in the host defense system. The prevalence and significance of this modification in eukaryotes has been unclear until recently. Here we discuss recent publications documenting the presence of 6mA in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans, consider possible roles for this DNA modification in regulating transcription, transposable elements and trans-generational epigenetic inheritance, and propose 6mA as a new epigenetic mark in eukaryotes.

Introduction

DNA methylation is a fundamental epigenetic process. The most common DNA modification in eukaryotes is 5-methylcytosine (5mC)1. In contrast, N6-methyladenine (6mA)2 is the most prevalent DNA modification in prokaryotes3. Early reports debated the existence and abundance of 6mA in eukaryotes1, 4. Some unicellular eukaryotes, such as ciliates and green algae, contain both 6mA and 5mC in their genomes, but the biological significance of these modifications in these organisms had remained largely uncharacterized until recently5.

DNA methylation studies in mammals and plants have focused on 5mC because of its widespread distribution6. 5mC has been shown to participate in genomic imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation, transposon suppression, gene regulation and epigenetic memory maintenance7–9. In contrast, prokaryotes use 6mA as the major DNA modification to discriminate the host DNA from foreign pathogenic DNA and protect the host genome via the restriction–modification (R–M) system. In this system, the host DNA is modified by methyltransferases at restriction sites, conferring the host genome with resistance to digestion. Unmethylated foreign DNA is recognized by restriction enzymes and cleaved10. In addition to its critical role in the R-M system, 6mA also participates in bacterial DNA replication and repair, transposition, nucleoid segregation, and gene regulation11, 12. Certain bacterial 6mA methyltransferases such as Dam13 and CcrM do not have restriction enzyme counterparts and have been shown to play important roles in multiple cellular processes14. So far, the R–M system has not been found in eukaryotes.

In this Progress article, we discuss the recent discoveries of 6mA in the multicellular eukaryotes Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster15, 16, and the unicellular algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, where a detailed analysis of 6mA distribution was also reported17. We describe the prevalence of 6mA and methods of detecting this modification, and discuss the enzymes responsible for regulating 6mA and the potential functional roles for 6mA in regulating epigenetic information in eukaryotes.

The prevalence of 6mA

Most eukaryotic 6mA research has focused on unicellular protists, including the ciliates Tetrahymena pyriformis18 and Paramecium aurelia19, and the green algae C. reinhardtii5. 6mA accounts for ~0.4% – 0.8% of the total adenines in these genomes17, 20, 21, which is several folds lower than the prevalence of 5mC in mammals and plants22. Interestingly, there have also been sporadic reports suggesting the presence of 6mA in more recently evolved organisms including mosquito23, plants24, 25, and even mammals26, 27. Recently, 6mA was detected by multiple approaches in the genomic DNA of two metazoans, C. elegans (0.01–0.4%)15 and D. melanogaster (0.001–0.07%)16.

Detection of 6mA

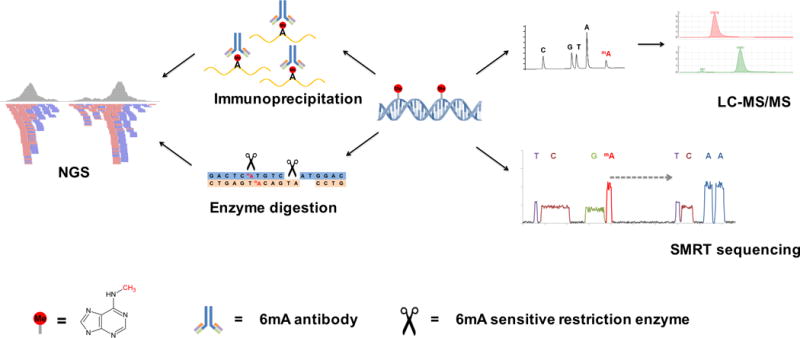

In order to monitor the presence and dynamics of 6mA in eukaryotic genomes, sensitive techniques are required (FIG. 1). An antibody against N6-methyladenine can detect N6-adenine methylation in eukaryotic mRNAs28–30, and this was used to detect and enrich for N6-methyladenine in DNA15–17. The 6mA antibody can be used to detect methylated DNA by dot blotting and to immunoprecipitate (IP) methylated DNA for sequencing. Antibody detection, however, is not quantitative and may be confounded by recognition of other adenine base modifications (such as 1-methyladenine (1mA) or 6mA in RNA). Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) provides the most unambiguous method to detect and quantify modified nucleotides31. However, while the high sensitivity of this approach allows for detection of many low abundance nucleotide modifications, both antibody detection and LC-MS/MS results could be confounded by bacterial contamination and therefore need to be cautiously evaluated.

Figure 1. Methods to detect 6mA in genomic DNA.

(Left) An antibody against N6-methyladenine can sensitively recognize 6mA and enrich 6mA-containing DNA for subsequent next generation sequencing (NGS); 6mA-sensitive restriction enzymes can specifically recognize either methylated or unmethylated adenines in their recognition sequence motifs, and this can be captured by sequencing to determine the exact locations of 6mA. (Right) Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) can differentiate methylated adenine from unmodified adenine and quantify the 6mA/A ratio by normalization to a standard curve; single molecule real time (SMRT) sequencing can detect modified nucleotides by measuring the rate of DNA base incorporation (dashed arrow) during sequencing.

Certain restriction enzymes are sensitive to nucleotide methylation and can be used to distinguish between methylated or unmethylated nucleotides in the context of their recognition sequences32 (FIG. 1). For instance, DpnI digests 5′-G6mATC-3′ sites, whereas DpnII digests unmethylated 5′-GATC-3′ sites33. Restriction enzyme digestion-based methods can thus sensitively and accurately determine the presence of 6mA at single-base resolution; however, these enzymes are restricted to revealing 6mA in specific sequence contexts34, which may not be recapitulated in all organisms. Single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing offers another option to detect DNA modifications35. SMRT sequencing provides both accurate sequence reads and determines the kinetics of nucleotide incorporations during synthesis. Different DNA modifications induce unique kinetic signatures that can be used for accurate and sequence-specific detection of modifications35, 36. SMRT sequencing has been used to map 6mA and 5mC simultaneously in Escherichia coli37 and 6mA in C. elegans15. However, SMRT sequencing cannot distinguish between 6mA and 1mA, and therefore must be coupled with LC-MS/MS in order to assess the relative contributions of the two modifications to the observed methylated adenine signals obtained from SMRT sequencing. SMRT sequencing is also still prohibitively expensive, impeding the extensive application on larger eukaryotic genomes.

For genomes with a low abundance of DNA modifications, the sensitivity and specificity of detection methods need to be balanced. High sensitivity but low specificity may generate false positive results, while high specificity but low sensitivity may miss weak signals. For a rare DNA modification, cross-validation by multiple strategies is indispensable to achieve the relative high sensitivity and high specificity.

Genomic distributions and sequence motifs

Mapping genomic distributions can be an effective first step for uncovering potential functions of DNA modifications7, 9, 38. In the latest studies15–17, immunoprecipitation of 6mA-containing DNA for subsequent high-throughput sequencing (6mA-IP-seq) or SMRT sequencing was used to identify the genomic distribution patterns of 6mA in C. elegans, D. melanogaster and C. reinhardtii, which were found to differ among these organisms: 6mA is broadly and evenly distributed across the genome of C. elegans, whereas in D. melanogaster, 6mA is enriched at transposable elements. In contrast, 6mA is highly enriched around transcription start sites (TSS) in the C. reinhardtii genome. Reminiscent of the genomic distribution of 5mC, 6mA localization patterns are thus species-specific, likely reflecting different functions and mechanisms of biogenesis6. By extension, the distinctive distribution patterns of 6mA in these three organisms may suggest diverse functional roles.

In prokaryotes, most of the 6mA sites are located within palindromic sequences39. Similar 6mA sites have also been identified in the genome of Tetrahymena thermophila40. Nearest-neighbor analyses assisted by 3H labeling revealed that the methylation in T. thermophila occurs at the sequence 5′-NAT-3′41, which is similar to the N6-adenine methylation motif found in C. reinhardtii17. Restriction enzyme analysis followed by next generation sequencing (FIG. 1) was used to determine the methylation status of each CATG and GATC site in C. reinhardtii. About 1/5 – 1/3 of the 6mAs were estimated to be located within these two motifs, and a majority of them (over 90%) were methylated in almost all DNA samples analyzed. Others most likely occur at 5′-NATN-3′ sequences, which was also predicted to be an N6-adenine methylation motif by a photo-crosslinking-based profiling method (6mA-CLIP-exo) that provides higher resolution information than regular IP-based profiling17.

Surprisingly, the sequence motifs identified in C. elegans are completely different from those in lower eukaryotes and bacteria. Using SMRT sequencing two motifs, AGAA and GAGG, were identified15. Sites with high abundance 6mA are most strongly associated with GAGG, whereas lower abundance 6mA sites are most strongly associated with AGAA. However, these motifs represent a fraction (~10%) of the total methylated adenines suggesting that additional factors beyond DNA sequence determine whether adenines are methylated in C. elegans. In D. melanogaster, conserved sequence motifs containing 6mA are yet to be reported16. The different N6-adenine methylation motifs found in C. elegans and C. reinhardtii suggest potential diverse biological functions in distant organisms.

Methyltransferases and demethylases

N6-methyladenine is the most abundant internal modification in mRNAs, and is widely conserved in eukaryotes. mRNA methylation is catalyzed by a methyltransferase complex and reversed by demethylases42–45. Enzymes responsible for DNA N6-adenine methylation in eukaryotes were previously unknown. Computation-based sequence analysis predicted the existence of homologs of the bacterial DNA adenine methyltransferases dam and m.MunI in the genomes of diverse eukaryotic organisms46. However, other DNA and RNA methyltransferase and demethylase proteins could also have evolved to catalyze DNA N6-adenine methylation in eukaryotic species37 (FIG. 2a).

Figure 2. DNA methyltransferases and demethylases.

a | Three families of DNA methyltransferases and two families of demethylases in 10 different model organisms are shown in a simplified phylogenetic tree. Color codes represent the reported presence of 6mA and/or 5mC in the corresponding organism (not the activity of the mentioned enzymes). The MT-A70 family proteins are widely conserved in eukaryotes but are missing in E. coli. They function as the RNA methyltransferases in plants and animals but appear to serve as the DNA 6mA methyltransferase in C. elegans. The Tet family proteins are DNA cytosine demethylases but have been proposed to demethylate adenines in D. melanogaster. The AlkB family proteins are conserved in all the organisms shown, and are DNA 6mA demethylases in C. elegans. The black dot indicates at least one member of each protein family exists in the corresponding organism. * The D. melanogaster genome contains a low level of 5mC (~0.03% of total cytosines)71. b | Two members — METTL3 and METTL14 — of the MT-A70 family are known to catalyze N6-adenine methylation in mammalian mRNA, while FTO and ALKBH5, members of the AlkB family, have been found to demethylate N6-methyladenine in mRNA. DAMT-1 is an MT-A70 family member that potentially mediates DNA 6mA methylation in C. elegans. An AlkB family member, NMAD-1, was identified as a demethylase in C. elegans. In D. melanogaster, the potential 6mA demethylase DMAD is a member of the Tet family proteins.

6mA methyltransferases

The DNMT family functions as 5mC methyltransferases in animals47. Although widely conserved, these proteins have been lost in certain species, including in C. elegans and D. melanogaster (FIG. 2a and Table 1). A family of enzymes containing an MT-A70 domain has evolved from the m.MunI-like 6mA DNA methyltransferase of bacteria46. This family includes yeast and mammalian mRNA methyltransferases (Ime4 and Kar4 in yeast and METTL3 and METTL14 in humans)44, 46, 48. In humans, MT-A70 is the S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) binding subunit, which catalyzes mRNA N6-adenine methylation48. C. elegans encodes a member of this family, DAMT-1. Over-expression of DAMT-1 in insect cells led to elevated 6mA in genomic DNA, whereas the expression of DAMT-1 with a mutated catalytic domain did not affect 6mA levels. In C. elegans, knockdown of damt-1 decreased 6mA levels in genomic DNA15. These data suggest that DAMT-1 is likely a 6mA methyltransferase in C. elegans (FIG. 2b and Table 1), although direct biochemical evidence is still needed to confirm this possibility. In humans, METTL3 and METTL14 exhibit weak methylation activity on DNA44. Another mammalian MT-A70-type protein, METTL4, is the closest ortholog of DAMT-1 in humans; however, its function has not been tested. The high evolutionary conservation and broad distribution of the MT-A70 family proteins raises the possibility that 6mA might be present in other eukaryotes, including in mammals.

Table 1. Potential N6-adenine methyltransferases and demethylases.

Protein family and catalytic domain information was derived from the Pfam and Uniprot databases. MTases, Methyltransferases; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine;

| Protein | Family | Catalytic domain | Substrate | Organism | Evidences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dam | Dam-like | SAM-dependent MTases | DNA | E. Coli | In vitro and in vivo13 |

| DNMT1 | DNMT | SAM-dependent MTases C5-type | DNA | Human | In vitro and in vivo47 |

| METTL3–METTL14 complex | MT-A70 | SAM-dependent MTases | RNA | Human | In vitro and in vivo44 |

| DAMT-1 | MT-A70 | SAM-dependent MTases | DNA | C. elegans | In vivo15 |

| FTO/ALKBH5 | AlkB | 2OG-FeII Oxygenase superfamily[ | RNA | Human | In vitro and in vivo43, 45 |

| NMAD-1 | AlkB | 2OG-FeII Oxygenase superfamily | DNA | C. elegans | In vitro and in vivo15 |

| Tet2 | Tet | CD (Cys-rich insert and Double-Stranded Beta-Helix (DSBH) domain) | DNA | Human | In vitro and in vivo52[Au: Isn’t Ref. 52 about TET2 only?] |

| DMAD | Tet | CD (Cys-rich insert and Double-Stranded Beta-Helix (DSBH) domain) | DNA | D. melanogaster | In vivo16 |

6mA demethylases

Proteins of the AlkB family catalyze demethylation of various methylated DNA and RNA nucleotides49. For instance, homologues of the AlkB family members FTO and ALKBH5 have been shown to demethylate mRNA N6-methyladenine in eukaryotes43, 45. C. elegans encodes five AlkB family members. Deletion of one member, nmad-1, caused elevated DNA 6mA levels in vivo, and purified NMAD-1 catalyzes N6-deoxyadenine demethylation in vitro15 (FIG. 2b and Table 1. Together, these results demonstrated that NMAD-1 is a 6mA demethylase in C. elegans.

D. melanogaster nuclear extracts possess DNA 6mA demethylation activity. Interestingly the demethylation activity of these nuclear extracts inversely correlates with 6mA levels at the time of extraction16. (Or Interestingly, these nuclear extracts have the highest 6mA demethylation activity when extracted at a time point when 6mA levels are the lowest16.), The homolog of the 5mC demethylase Tet50 (renamed dmad), when added to nuclear extracts, increased the 6mA demethylating activity16. In vitro assays showed that the nuclear extract from dmad mutants lost demethylation activity and the addition of purified DMAD recovered the demethylation activity. DMAD is lowly expressed at early embryonic stages (45 minutes after fertilization) but is induced at later stages, indicating it has a role in removing 6mA during embryogenesis16. Genomic DNA isolated from brains of dmad mutants has ~100-fold higher levels of 6mA than wild-type flies16. Taken together, these data suggest that DMAD is a 6mA demethylase in D. melanogaster (FIG. 2b). This is somewhat surprising since the Tet proteins are evolutionary conserved DNA cytosine demethylases rather than adenine demethylases. The available crystal structures of Tet catalytic domains, unlike those of the AlkB family, revealed an active site that may not accommodate a purine base51, 52. However, since 5mC levels in D. melanogaster are quite low, DMAD could have evolved as a 6mA demethylase instead of oxidizing 5mC; further biochemical and structural investigations will provide additional insights. Interestingly, D. melanogaster has an ortholog of NMAD-1 (CG4036), and it will be interesting to determine whether CG4036 mediates demethylation of 6mA, in addition to DMAD.

Functions of 6mA

While DNA 6mA has been well-studied in prokaryotes, its eukaryotic biological functions remain elusive21. There is no known eukaryotic equivalent of the bacterial R-M system, ruling out a possible role for 6mA in this context. The addition of a methyl group at the N6-position of adenine slightly reduces base-pairing energy53 and could enhance or interfere with protein-DNA interactions54–56. Treatment of cancer cells with the nucleoside N6-methyldeoxyadenosine induces their differentiation57. Transgenic incorporation of bacterial 6mA methyltransferase (dam) into tobacco plants induced N6-adenine methylation at most GATC sites and changed the leaf and florescence morphology58. Collectively, these phenotypes suggest DNA adenine methylation may have a role in regulating multiple biological processes.

Transcription

Methylation of adenines could impact transcription by modifying transcription factor binding or altering chromatin structure. In bacteria, 6mA has been shown to regulate transcription59, 60, raising the possibility that a similar function has been retained in eukaryotes. Interestingly, N6 adenine methylation has been shown to have opposite effects on transcription factor-binding in mammals and in plants. Transfected DNA methylated at the N6 position of adenines decreased the DNA binding affinity of transcription factors in mammalian cells54, 56. In plants, the binding affinity of the zinc finger protein AGP1 to DNA can be enhanced by N6 adenine methylation of the target sequence55. Additionally, using a transient expression system in barley, transcription was found to increase in 6mA-modified reporter plasmids whereas 5mC had little or no effect on transcription efficiency61.

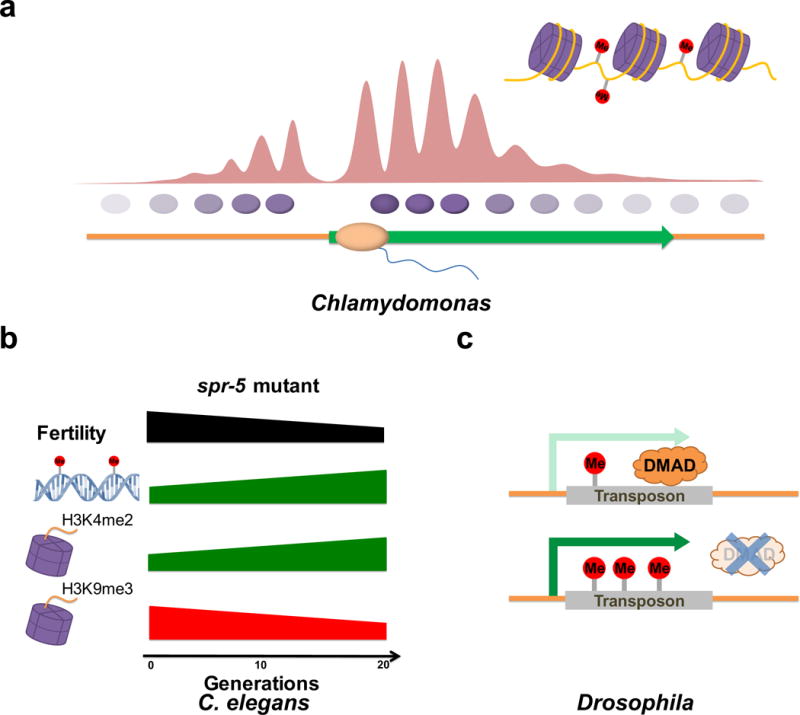

In C. reinhardtii, 6mA is enriched around the TSS of more than 14,000 genes, most of which are actively transcribed, and most of these 6mA sites are methylated in almost every cell analyzed17. In contrast, silent genes have lower 6mA levels around their TSS. Therefore, it appears that 6mA is a general mark of active genes, although it is currently unclear whether it plays a role in the dynamic regulation of gene expression (FIG 3a). By contrast, 5mC also exists in the genome of C. reinhardtii, but is located at gene bodies and is correlated with transcription repression. It is unclear what role, if any, 6mA has during transcription in C. elegans. Interestingly, 6mA levels were elevated in mutants with elevated levels of histone H3 lysine 4 dimethylation (H3K4me2), which is a mark associated with active transcription15. This suggests that 6mA may also mark active genes in C. elegans as it does in C. reinhardtii17(FIG. 3b)

Figure 3. 6mA genomic distribution and function.

a | Single-base resolution maps of 6mA in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii reveal a periodic distribution pattern, with depletion at active transcription start sites (TSS) and enrichment around them. Portrayed are the nucleosomes, which are mutually exclusive with 6mA. The phasing level of nucleosomes varies from highly phased near the TSS to randomly positioned ~1 kb from the TSS, where the 6mA methylation level also drops. 6mA sites are found in the linker regions. b | In C. elegans spr-5 mutants, 6mA and H3K4me2 levels increase progressively from generation to generation in conjunction with a decline of H3K9me3 levels and fertility. c | DNA 6mA methylation is correlated with increased transposon expression in D. melanogaster. Loss of the demethylase DMAD leads to elevated 6mA levels and increased expression of transposons.

In D. melanogaster 6mA was proposed to promote transposon expression. 6mA-IP-seq assays revealed enrichment of 6mA on transposons, and loss of the putative demethylase DMAD led to increased transposon expression (FIG. 3c)16. Thus, the latest discoveries in three evolutionarily distant organisms suggest a correlation of 6mA with elevated gene expression, although it remains to be seen how general this mechanism is and whether 6mA has evolved to have different functions in different species and/or different contexts. Important future experiments will involve directing DNA methyltransferases or demethylases to specific loci and examining the effects on transcription of the addition or removal of 6mA, respectively.

DNA methylation and nucleosome positioning

Previous studies in T. thermophile showed that 6mA levels were lower in nucleosomal DNA than in linker DNA62. Neither C. elegans nor D. melanogaster revealed a nucleosome positioning bias for 6mA15, 16. However, the C. elegans study was performed on mixed tissues, and specific genomic patterns might only emerge in a more detailed tissue-specific examination. In C. reinhardtii, on the other hand, 6mA was found to be preferentially located at TSS-proximal linker DNA (FIG. 3a). This could be explained by the methylation machinery favoring linker DNA, potentially due to physical ease of access40, or by 6mA regulating nucleosome positioning. Interestingly, methylation in CG repeats in certain algae species occurs at extreme densities, which disfavors nucleosome assembly and thus dictates nucleosome positioning63. Therefore, DNA methylation could provide a general mechanism of controlling nucleosome positioning in unicellular eukaryotes.

6mA as an epigenetic mark

In prokaryotes, 6mA methyltransferases methylate adenine in the context of specific sequence motifs11, but eukaryotic 6mA does not appear to be as strongly dependent on sequence motif recognition. In C. reinhardtii 6mA occurs in multiple sequences, mainly located at ApT dinucleotides, resembling the 5mC methylation at CpG dinucleotides in mammals17. During multiple fission cell cycles, the 6mA levels are stably maintained. Single-base maps indicated that most of the individual 6mA sites are faithfully conserved under variant culture conditions, reinforcing the speculation of 6mA as a heritable epigenetic mark17. Though a 6mA methyltransferase has yet to be characterized in C. reinhardtii, there is very likely to be a mechanism of inheriting 6mA signatures from parent cells to daughter cells. In C. elegans, deletion of the H3K4me2 demethylase spr-5 causes a trans-generational progressive loss of fertility64. This fertility defect coincides with a progressive accumulation of H3K4me2 and a decline in the levels of the repressive mark H3K9me365. In spr-5 mutant worms 6mA also increases across generations; deletion of the 6mA demethylase nmad-1 accelerates, whereas deletion of the potential 6mA methyltransferase damt-1 suppresses the progressive fertility defect of spr-5 mutant worms (FIG. 3b). Additionally, deleting damt-1 suppressed the accumulation of H3K4me2, suggesting that N6-adenine methylation and H3K4 dimethylation might be co-regulated and reinforce each other15. While it remains to be determined whether 6mA or H3K4me2 can themselves transmit epigenetic information across generations, these modifications accumulate when epigenetic information is improperly inherited. These discoveries raise the possibility that 6mA may act as an epigenetic mark that carries heritable epigenetic information in eukaryotes.

Summary and Perspective

Both 5mC and 6mA were discovered in eukaryotic genomes decades ago1, 18. Research has focused on characterizing 5mC due to its abundance in mammals and plants. Multiple functions of 5mC have been revealed, while studies of 6mA have been very limited in eukaryotes. It is well known that 5mC can be spontaneously deaminated, which results in a C-to-T mutation66; thus, organisms possessing 5mC tend to lose CpG dinucleotides due to deamination of the methylated cytosines9. Conversely, 6mA does not tend towards spontaneous mutations, which obviously could be advantageous for the genomic stability.

Adenine methylation in eukaryotic mRNA was recently shown to have profound effects on gene expression42. The potential roles of 6mA DNA in shaping gene expression remain largely unknown. The methyl group of RNA N6-methyladenine can destabilize the Watson-Crick base pairing by ~1.0 kcal/mol67, 68, and this was shown to induce an “m2A-switch” mechanism that alters RNA structure and thus binding by proteins69. The same property in DNA could affect transcription, replication, and other processes that require strand separation or DNA bending. Furthermore, the methyl group may facilitate or inhibit recognition and binding by DNA-binding proteins to regulate gene expression. In mammalian cells, FTO-catalyzed demethylation of RNA N6-methyladenines generates two newly discovered intermediates, N6-hydroxymethyladenosine (hm6A) and N6-formyladenosine (f6A), in non-coding RNA and mRNA70. As hm6A and f6A are very stable modifications, it is possible that they are not merely intermediates but have regulatory functions. It remains to be seen whether similar modifications are produced during oxidative demethylation reactions of DNA 6mA, and, if they exist, whether they have any biological role. Such modifications could further de-stabilize the DNA duplex or produce new protein binding sites.

It is interesting to note that C. elegans and D. melanogaster possess little or no 5mC in their genomic DNA, similar to some other 6mA-containing organisms, such as P. aurelia19 and T. thermophila62. C. reinhardtii, however, contains both 6mA and 5mC in its genome, but the relatively overall low level of 5mC combined with its unusual enrichment at exons suggest different functions for 5mC compared to more recently evolved plants and animals, where it is mostly a mark of gene silencing6. It is possible that the relative change in 6mA and 5mC abundance and function could have had diverse evolutionary consequences. N6-adenine methylation could be a major DNA methylation mechanism that affects gene expression in certain eukaryotes, as revealed from the recent studies15–17. In other systems, it may play a complementary role to the functionally more dominant 5mC DNA methylation. The presence of 6mA-methyltransferase homologs in distinct species raises the possibility that 6mA may be present in many more organisms, including mammals. Whether the relative biological importance of 6mA has declined in conjunction with its lower abundance in the more recently evolved organisms remains to be seen. We speculate that 6mA could have evolved a more specialized function in these species. With the advent of new, sensitive detection techniques, we are now poised to probe in detail the function and precise genomic distribution of this DNA modification throughout the tree of life.

Online summary.

N6-adenine methylation (6mA) is a DNA modification that may carry heritable information in eukaryotes.

6mA is enriched at the transcription start sites (TSS) in the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii genome, and specifically marks linker DNA between nucleosomes.

In C. elegans a member of the ALKB family mediates demethylation of 6mA, while an MT-A70 family member promotes adenine methylation (6mA).

D. melanogaster DMAD catalyzes 6mA demethylation, which affects transposon expression.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to colleagues whose work was not cited due to space limitation. C.H. is supported by the US National Institutes of Health grant HG006827 and is an investigator of Howard Hughes Medical Institute. MAB is a Special Fellow of the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. Work in the Greer lab is supported by a National Institute on Aging of the NIH grant (AG043550). Work in the Shi lab is supported by grants from the NIH (CA118487 and MH096066), the Ellison Medical Foundation and the Sam Waxman Cancer Research Foundation. YS is an American Cancer Society Research Professor.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

YS is a co-founder of Constellation Pharmaceuticals, Inc and a member of its scientific advisory board. The other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Vanyushin BF, Tkacheva SG, Belozersky AN. Rare bases in animal DNA. Nature. 1970;225:948–9. doi: 10.1038/225948a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunn DB, Smith JD. Occurrence of a new base in the deoxyribonucleic acid of a strain of Bacterium coli. Nature. 1955;175:336–7. doi: 10.1038/175336a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vanyushin BF, Belozersky AN, Kokurina NA, Kadirova DX. 5-methylcytosine and 6-methylamino-purine in bacterial DNA. Nature. 1968;218:1066–7. doi: 10.1038/2181066a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unger G, Venner H. Remarks on minor bases in spermatic desoxyribonucleic acid. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1966;344:280–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hattman S, Kenny C, Berger L, Pratt K. Comparative study of DNA methylation in three unicellular eucaryotes. J Bacteriol. 1978;135:1156–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.135.3.1156-1157.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng SH, et al. Conservation and divergence of methylation patterning in plants and animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:8689–8694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002720107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith ZD, Meissner A. DNA methylation: roles in mammalian development. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:204–20. doi: 10.1038/nrg3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones PA, Takai D. The role of DNA methylation in mammalian epigenetics. Science. 2001;293:1068–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1063852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:484–92. doi: 10.1038/nrg3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naito T, Kusano K, Kobayashi I. Selfish behavior of restriction-modification systems. Science. 1995;267:897–9. doi: 10.1126/science.7846533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wion D, Casadesus J. N6-methyl-adenine: an epigenetic signal for DNA-protein interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:183–92. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vasu K, Nagaraja V. Diverse functions of restriction-modification systems in addition to cellular defense. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013;77:53–72. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00044-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urieli-Shoval S, Gruenbaum Y, Razin A. Sequence and substrate specificity of isolated DNA methylases from Escherichia coli C. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:274–80. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.274-280.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright R, Stephens C, Shapiro L. The CcrM DNA methyltransferase is widespread in the alpha subdivision of proteobacteria, and its essential functions are conserved in Rhizobium meliloti and Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5869–77. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5869-5877.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greer EL, et al. DNA Methylation on N6-Adenine in C. elegans. Cell. 2015;161:868–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang G, et al. N6-methyladenine DNA modification in Drosophila. Cell. 2015;161:893–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu Y, et al. N6-methyldeoxyadenosine marks active transcription start sites in chlamydomonas. Cell. 2015;161:879–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorovsky MA, Hattman S, Pleger GL. (6 N)methyl adenine in the nuclear DNA of a eucaryote, Tetrahymena pyriformis. J Cell Biol. 1973;56:697–701. doi: 10.1083/jcb.56.3.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummings DJ, Tait A, Goddard JM. Methylated bases in DNA from Paramecium aurelia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;374:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(74)90194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hattman S. DNA-[adenine] methylation in lower eukaryotes. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2005;70:550–8. doi: 10.1007/s10541-005-0148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ratel D, Ravanat JL, Berger F, Wion D. N6-methyladenine: the other methylated base of DNA. Bioessays. 2006;28:309–15. doi: 10.1002/bies.20342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki MM, Bird A. DNA methylation landscapes: provocative insights from epigenomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:465–76. doi: 10.1038/nrg2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams RL, McKay EL, Craig LM, Burdon RH. Methylation of mosquito DNA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;563:72–81. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(79)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashapkin VV, Kutueva LI, Vanyushin BF. The gene for domains rearranged methyltransferase (DRM2) in Arabidopsis thaliana plants is methylated at both cytosine and adenine residues. Febs Letters. 2002;532:367–372. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03711-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanyushin BF, Alexandrushkina NI, Kirnos MD. N6-Methyladenine in Mitochondrial-DNA of Higher-Plants. Febs Letters. 1988;233:397–399. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kay PH, et al. Evidence for Adenine Methylation within the Mouse Myogenic Gene Myo-D1. Gene. 1994;151:89–95. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90636-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang W, et al. Determination of DNA adenine methylation in genomes of mammals and plants by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. RSC Advances. 2015;5:64046–64054. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jia G, et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:885–7. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dominissini D, et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. 2012;485:201–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo GZ, et al. Unique features of the m6A methylome in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5630. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frelon S, et al. High-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry measurement of radiation-induced base damage to isolated and cellular DNA. Chem Res Toxicol. 2000;13:1002–10. doi: 10.1021/tx000085h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts RJ, Macelis D. REBASE–restriction enzymes and methylases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:268–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lacks S, Greenberg B. Complementary specificity of restriction endonucleases of Diplococcus pneumoniae with respect to DNA methylation. J Mol Biol. 1977;114:153–68. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laird PW. Principles and challenges of genomewide DNA methylation analysis. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:191–203. doi: 10.1038/nrg2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flusberg BA, et al. Direct detection of DNA methylation during single-molecule, real-time sequencing. Nat Methods. 2010;7:461–5. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schadt EE, et al. Modeling kinetic rate variation in third generation DNA sequencing data to detect putative modifications to DNA bases. Genome Res. 2013;23:129–41. doi: 10.1101/gr.136739.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fang G, et al. Genome-wide mapping of methylated adenine residues in pathogenic Escherichia coli using single-molecule real-time sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:1232–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones PL, et al. Methylated DNA and MeCP2 recruit histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nat Genet. 1998;19:187–91. doi: 10.1038/561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Touzain F, Petit MA, Schbath S, El Karoui M. DNA motifs that sculpt the bacterial chromosome. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:15–26. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karrer KM, VanNuland TA. Methylation of adenine in the nuclear DNA of Tetrahymena is internucleosomal and independent of histone H1. Nucleic Acids Research. 2002;30:1364–1370. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.6.1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bromberg S, Pratt K, Hattman S. Sequence Specificity of DNA Adenine Methylase in the Protozoan Tetrahymena Thermophila. Journal of Bacteriology. 1982;150:993–996. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.2.993-996.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fu Y, Dominissini D, Rechavi G, He C. Gene expression regulation mediated through reversible m(6)A RNA methylation. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2014;15:293–306. doi: 10.1038/nrg3724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jia GF, et al. N6-Methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nature Chemical Biology. 2011;7:885–887. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu J, et al. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:93–5. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng GQ, et al. ALKBH5 Is a Mammalian RNA Demethylase that Impacts RNA Metabolism and Mouse Fertility. Molecular Cell. 2013;49:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iyer LM, Abhiman S, Aravind L. Natural History of Eukaryotic DNA Methylation Systems. Modifications of Nuclear DNA and Its Regulatory Proteins. 2011;101:25–104. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387685-0.00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song J, Rechkoblit O, Bestor TH, Patel DJ. Structure of DNMT1-DNA complex reveals a role for autoinhibition in maintenance DNA methylation. Science. 2011;331:1036–40. doi: 10.1126/science.1195380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bokar JA, Shambaugh ME, Polayes D, Matera AG, Rottman FM. Purification and cDNA cloning of the AdoMet-binding subunit of the human mRNA (N6-adenosine)-methyltransferase. RNA. 1997;3:1233–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trewick SC, Henshaw TF, Hausinger RP, Lindahl T, Sedgwick B. Oxidative demethylation by Escherichia coli AlkB directly reverts DNA base damage. Nature. 2002;419:174–8. doi: 10.1038/nature00908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tahiliani M, et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324:930–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang CG, et al. Crystal structures of DNA/RNA repair enzymes AlkB and ABH2 bound to dsDNA. Nature. 2008;452:961–5. doi: 10.1038/nature06889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu L, et al. Crystal structure of TET2-DNA complex: insight into TET-mediated 5mC oxidation. Cell. 2013;155:1545–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bang J, Bae SH, Park CJ, Lee JH, Choi BS. Structural and Dynamics Study of DNA Dodecamer Duplexes That Contain Un-, Hemi-, or Fully Methylated GATC Sites. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2008;130:17688–17696. doi: 10.1021/ja8038272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tronche F, Rollier A, Bach I, Weiss MC, Yaniv M. The rat albumin promoter: cooperation with upstream elements is required when binding of APF/HNF1 to the proximal element is partially impaired by mutation or bacterial methylation. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:4759–66. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.11.4759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sugimoto K, Takeda S, Hirochika H. Transcriptional activation mediated by binding of a plant GATA-type zinc finger protein AGP1 to the AG-motif (AGATCCAA) of the wound-inducible Myb gene NtMyb2. Plant J. 2003;36:550–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lichtsteiner S, Schibler U. A glycosylated liver-specific transcription factor stimulates transcription of the albumin gene. Cell. 1989;57:1179–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ratel D, et al. The bacterial nucleoside N-6-methyldeoxyadenosine induces the differentiation of mammalian tumor cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2001;285:800–805. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Blokland R, Ross S, Corrado G, Scollan C, Meyer P. Developmental abnormalities associated with deoxyadenosine methylation in transgenic tobacco. Plant Journal. 1998;15:543–551. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roberts D, Hoopes BC, Mcclure WR, Kleckner N. Is10 Transposition Is Regulated by DNA Adenine Methylation. Cell. 1985;43:117–130. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hernday A, Krabbe M, Braaten B, Low D. Self-perpetuating epigenetic pili switches in bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:16470–16476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182427199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rogers JC, Rogers SW. Comparison of the effects of N6-methyldeoxyadenosine and N5-methyldeoxycytosine on transcription from nuclear gene promoters in barley. Plant J. 1995;7:221–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.7020221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pratt K, Hattman S. Deoxyribonucleic-Acid Methylation and Chromatin Organization in Tetrahymena-Thermophila. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1981;1:600–608. doi: 10.1128/mcb.1.7.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huff JT, Zilberman D. Dnmt1-Independent CG Methylation Contributes to Nucleosome Positioning in Diverse Eukaryotes. Cell. 2014;156:1286–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Katz DJ, Edwards TM, Reinke V, Kelly WG. A C. elegans LSD1 demethylase contributes to germline immortality by reprogramming epigenetic memory. Cell. 2009;137:308–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Greer EL, et al. A Histone Methylation Network Regulates Transgenerational Epigenetic Memory in C-elegans. Cell Reports. 2014;7:113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Poole A, Penny D, Sjoberg BM. Confounded cytosine! Tinkering and the evolution of DNA. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:147–51. doi: 10.1038/35052091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kierzek E, Kierzek R. The thermodynamic stability of RNA duplexes and hairpins containing N6-alkyladenosines and 2-methylthio-N6-alkyladenosines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:4472–80. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roost C, et al. Structure and thermodynamics of N6-methyladenosine in RNA: a spring-loaded base modification. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:2107–15. doi: 10.1021/ja513080v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu N, et al. N(6)-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature. 2015;518:560–4. doi: 10.1038/nature14234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fu Y, et al. FTO-mediated formation of N6-hydroxymethyladenosine and N6-formyladenosine in mammalian RNA. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1798. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Capuano F, Mulleder M, Kok R, Blom HJ, Ralser M. Cytosine DNA Methylation Is Found in Drosophila melanogaster but Absent in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, and Other Yeast Species. Analytical Chemistry. 2014;86:3697–3702. doi: 10.1021/ac500447w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]