Abstract

Study Objectives:

To analyze the independent and combined relations of sleep duration and midday napping with coronary heart diseases (CHD) incidence along with the underlying changes of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors among Chinese adults.

Methods:

We included 19,370 individuals aged 62.8 years at baseline from September 2008 to June 2010, and they were followed until October 2013. Cox proportional hazards models and general linear models were used for multivariate longitudinal analyses.

Results:

Compared with sleeping 7– < 8 h/night, the hazard ratio (HR) of CHD incidence was 1.33 (95% CI = 1.10 to 1.62) for sleeping ≥ 10 h/night. The association was particularly evident among individuals who were normal weight and without diabetes. Similarly, the HR of incident CHD was 1.25 (95% CI = 1.05 to 1.49) for midday napping > 90 min compared with 1–30 min. When sleep duration and midday napping were combined, individuals having sleep duration ≥ 10 h and midday napping > 90 min were at a greater risk of CHD than those with sleeping 7– < 8 h and napping 1–30 min: the HR was 1.67 (95% CI = 1.04 to 2.66; P for trend = 0.017). In addition, longer sleep duration ≥ 10 h was significantly associated with increases in triglycerides and waist circumference, and a reduction in HDL-cholesterol; while longer midday napping > 90 min was related to increased waist circumference.

Conclusions:

Both longer sleep duration and midday napping were independently and jointly associated with a higher risk of CHD incidence, and altered lipid profile and waist circumference may partially explain the relationships.

Citation:

Yang L, Yang H, He M, Pan A, Li X, Min X, Zhang C, Xu C, Zhu X, Yuan J, Wei S, Miao X, Hu FB, Wu T, Zhang X. Longer sleep duration and midday napping are associated with a higher risk of CHD incidence in middle-aged and older Chinese: the Dongfeng-Tongji Cohort Study. SLEEP 2016;39(3):645–652.

Keywords: sleep duration, midday napping, incident CHD, prospective studies, follow-up

Significance.

The present study identifies a significant association of longer sleep and midday nap with incident CHD in middle-aged and older Chinese. Independent of other CHD risk factors, individuals with sleeping ≥ 10 h or napping > 90 min had 33% or 25% increased risk of CHD incidence respectively, and unfavorable changes in lipid profiles and waist circumference, compared with those who reported sleeping 7– < 8 h or napping 1–30 min. Moreover, individuals with sleeping ≥ 10 h and napping > 90 min simultaneously exhibited greater increased risk. Our findings suggest that appropriate duration of sleep and nap may complement other behavioral interventions for preventing CHD.

INTRODUCTION

Short and long sleep durations are linked to adverse long-term health outcomes, including metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, as well as cardiovascular disease (CVD).1–3 Since sleep deprivation is a common condition in modern society, a growing number of epidemiological studies have shown that shorter sleep duration is associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) incidence or mortality.4–8 In contrast, prospective studies on the relationship between longer sleep duration and CHD incidence or mortality were relatively limited,9–11 especially evidence supporting the impact of longer sleep duration on the risk of CHD incidence was scarce, except that an earlier study conducted in the Nurses' Health Study cohort found that prolonged sleep duration increased the risk of incident CHD.9 Thus it remains unclear whether long sleep duration is a real cause of incident CHD, especially in Chinese, who have different lifestyle and other CVD risk factors compared with that of Western population.

Midday napping is a common practice in China and is traditionally regarded as a healthy lifestyle.12 Due to the high prevalence of the practice in China, it is of particular interest to understand its health consequences. Until now, only one study examined the relationship of midday napping and CHD incidence in a non-Mediterranean population. This study suggested that regular long (> 60 min) midday napping was related to elevated risks of incident CHD in both sex, but they did not explore this association by other baseline characteristics or comorbid conditions, which may act as effect modifiers on the nap-incident CHD relationship.13

Therefore, we examined whether sleep duration and midday napping were independently and jointly associated with the risk of incident CHD in a large cohort of middle-aged and older Chinese adults. We further investigated whether the association could be modified by different characteristics or health status, as well as the underlying changes of CVD risk factors.

METHODS

Study Population

We analyzed data from the Dongfeng-Tongji (DFTJ) cohort which was reported in detail previously.14 Briefly, the primary aim of the DFTJ cohort was to investigate a wide range of lifestyle, dietary, psychosocial, occupational and environmental factors, and biochemical factors in relation to the development of chronic diseases. The Retirement Office and the Social Insurance Center at Dongfeng Motor Corporation (DMC) provided a list of the retired employees and invited them to participate in this study. All retired employees are covered by DMC's health-care service system and each participant has a unique medical insurance card number and ID. A total of 27,009 retired employees agreed and completed baseline questionnaires and medical examinations at health examination center in Dongfeng General Hospital between September 2008 and June 2010. In addition, fasting blood samples were collected before physical examinations using standardized procedures. Five years later, the participants were invited to the follow-up survey via telephone. In total, 25,978 individuals (96.2% of those at baseline) completed the follow-up until October 2013.

At the follow-up investigation, participants repeated questionnaire interview, physical examinations, and blood collection as those in the baseline survey. In this study, we excluded individuals with self-report CHD, stroke, or cancer at baseline (n = 5,865), and those with missing information related to sleep duration, midday napping, or other covariates (n = 743), resulting in a final study sample of 19,370 adults (8,534 men and 10,836 women with a mean age of 62.8 years). The study was approved by the Ethics and Human Subject committee of Tongji Medical College, and Dongfeng General Hospital, DMC. All study participants provided informed consents.

Assessment of Sleep Duration and Midday Napping

Information on sleep duration and midday napping was obtained by a self-administered questionnaire. Sleep duration was assessed by asking the following question: “What time did you usually go to sleep at night and wake up in the morning over the previous 6 months?” We categorized sleep duration into 5 groups: < 7 h, 7– < 8 h, 8– < 9 h, 9– < 10 h, ≥ 10 h. Midday napping was assessed by asking “Did you have a habit of taking midday nap over the previous 6 months?” Those who responded affirmatively were further asked about the duration of their napping. Midday napping was thereby divided into no napping (0 min), 1–30 min, 31–60 min, 61–90 min, and > 90 min.

Assessment of Covariates

Trained interviewers administered face to face semi-structured interview questionnaires and collected information on sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, education, and marital status), diet, and lifestyle such as smoking status (current, former, never), drinking status (current, former, never), and physical activity, occupational history, environmental exposures, and family and medical histories. Participants who were smoking at least one cigarette per day for more than half a year were defined as current smokers; those who were drinking at least one time per week for more than half a year were considered as current drinkers. Physical activity was defined as those who regularly exercised more than 20 min per day over the last 6 months. Standing height, weight, and waist circumference were measured with participants in light indoor clothing and without shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Participants were also asked about their medical history diagnosed by physicians, including CHD, stroke, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, or cancer. Hypertension was defined as individuals with self-reported physician diagnosis of hyper-tension, or blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mm Hg, or current use of antihypertensive medication. Hyperlipidemia was defined as total cholesterol > 5.72 mmol/L or triglycerides > 1.70 mmol/L at medical examination, or a previous physician diagnosis of hyperlipidemia, or current use of lipid-lowering medication. Diabetes was defined as self-reported physician diagnosis of diabetes, fasting glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, or taking oral hypoglycemic medication or insulin.

Blood lipids (total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-cholesterol], and low-density lipo-protein cholesterol [LDL-cholesterol]), fasting glucose levels, hepatic function, renal function, a complete blood count, and tumor-associated antigens were determined specifically for the DFTJ cohort study at the hospital's laboratory.

Ascertainment of Incident CHD

The outcome of interest was incident CHD, defined as non-fatal myocardial infarction (non-fatal MI), stable angina (SA), unstable angina (UA), and unspecified CHD, or CHD death that occurred after baseline survey but before October 2013. All retired employees are covered by DMC's health-care service system, and each participant has a unique medical insurance card number and ID, which make it easy to track health service use, disease incidence, and mortality through this medical insurance system and DMC-owned hospitals. Self-reported CHD on a follow-up questionnaire was identified through medical record reviews in the DMC hospitals. The diagnosis of CHD was made by cardiologists in the DMC hospitals according to the World Health Organization criteria and/ or stenoses ≥ 50% in at least 1 major coronary artery by coronary angiography.15 For suspected CHD, medical records were examined for signs or symptoms of ischemia, diagnostic enzymes or ECG. Expert panels at cardiovascular division in the DMC hospitals reviewed all available clinical information and confirmed CHD based on well-accepted international standards.15–17 Non-fatal MI was defined based on ECG, cardiac enzyme values, and typical symptoms. SA was considered as no change in frequency, duration, or intensity of symptoms within 6 weeks before admission.UA was considered as angina at rest, new onset of severe angina, or accelerated angina.18 CHD death was defined on the basis of the underlying cause of death recorded on death certificates as ICD-9: 410-41419 or ICD-10: I20-I25.20 A total of 2,058 incident cases of CHD were observed in the present study.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of the participants were reported as mean (SD) for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables. Cox proportional hazard regression, separately for sleep duration and midday napping, was performed to evaluate the associations of categories of sleep and nap duration with risk of incident CHD. The results were presented as hazards ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), with sleep duration of 7 to < 8 h and midday napping of 1–30 min as the reference groups, based on reports suggesting that 7 to < 8 h sleep and ≤ 30 min nap were beneficial.21,22 The detailed questionnaires collected information on a wide range of covariates. We chose covariates based on evidence from literature and relevance to sleep, nap, and CHD in this analysis. Potential confounders included age, sex, BMI, smoking status, drinking status, education, physical activity, baseline comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia), and family history of CHD. To determine whether the effect of sleep duration or midday napping on CHD incidence was independent of each other, we further adjusted for midday napping for the sleep-incident CHD relationship and sleep duration for the nap-incident CHD relationship. Additional adjustment for triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol, and waist circumference as well as sleep quality at baseline attenuated the association slightly (< 5% change in effect estimates), so these variables were not retained in our final models. We also tested the curvilinear relation by including linear and quadratic terms of sleep duration or midday napping in the regression models. Additionally, nonlinear trends of incident CHD risk were tested by restricted cubic spline Cox regression using 4 knots placed at the 5th, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentiles of sleep duration and midday napping, respectively, with 7 h for sleep duration and 30 min for midday napping as the reference groups. Stratified analyses were performed by baseline characteristics (including age [< 65, ≥ 65 years], sex, BMI [< 25, ≥ 25 kg/m2], current smoking [yes, no], physical activity [yes, no], hyper-tension [yes, no], hyperlipidemia [yes, no], and diabetes [yes, no]). Moreover, we tested the potential interaction by adding interaction terms of these covariates with sleep duration or midday napping, respectively. We further constructed Cox proportional hazard regression models to estimate the combined effects of sleep duration and midday napping on the risk of incident CHD, taking sleeping 7– < 8 h and napping 1–30 min as the reference category. Finally, we examined the relationships of sleep duration and midday napping with changes in CVD risk factors (including lipid profiles, fasting glucose, waist circumference, BMI, and blood pressure) using multivariate linear regression analyses. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.3 (SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC). A P value < 0.05 (two-sided test) was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

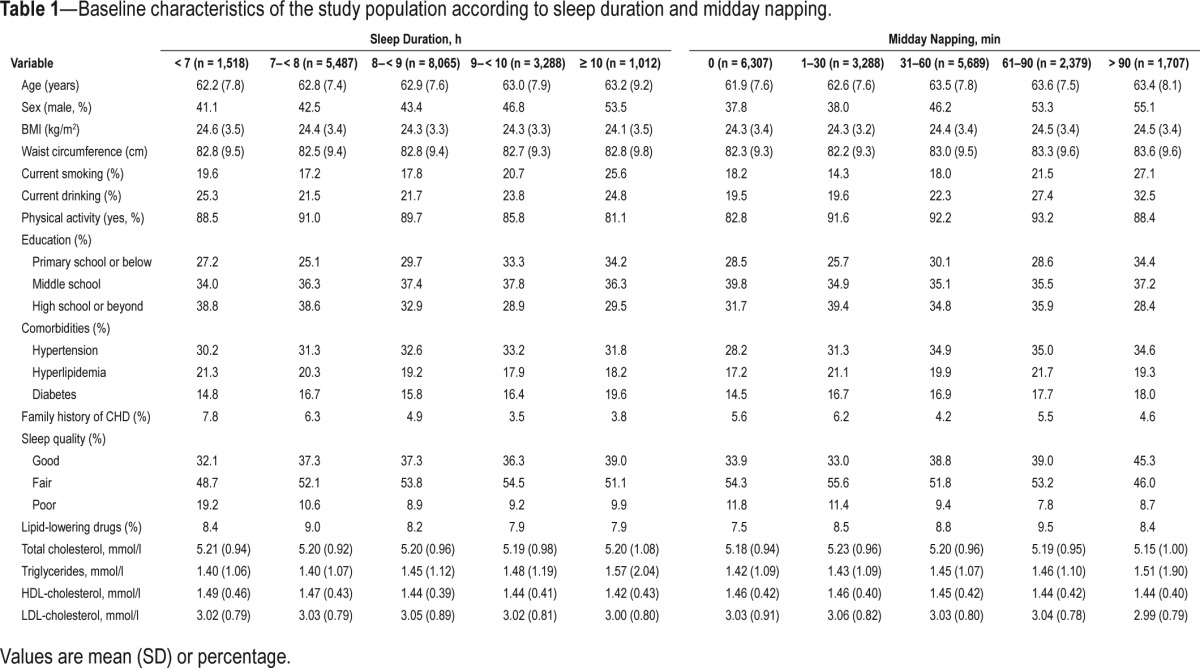

Baseline characteristics of the participants by categories of sleep duration and midday napping are shown in Table 1. Overall, 1,012 (5.2%) individuals reported sleeping ≥ 10 h/ night, and 1,707 (8.8%) reported napping > 90 min/day; only 247 (1.3%) reported < 6 h per night of sleep (15 CHD cases occurred). Compared with the reference groups, individuals with sleep duration ≥ 10 h or midday napping > 90 min were more likely to be males, current smokers, current drinkers, physically inactive, and present with higher triglycerides or lower HDL-cholesterol at baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population according to sleep duration and midday napping.

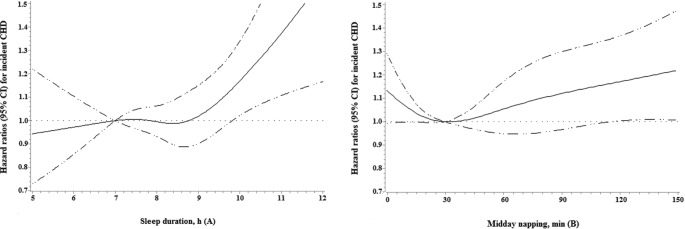

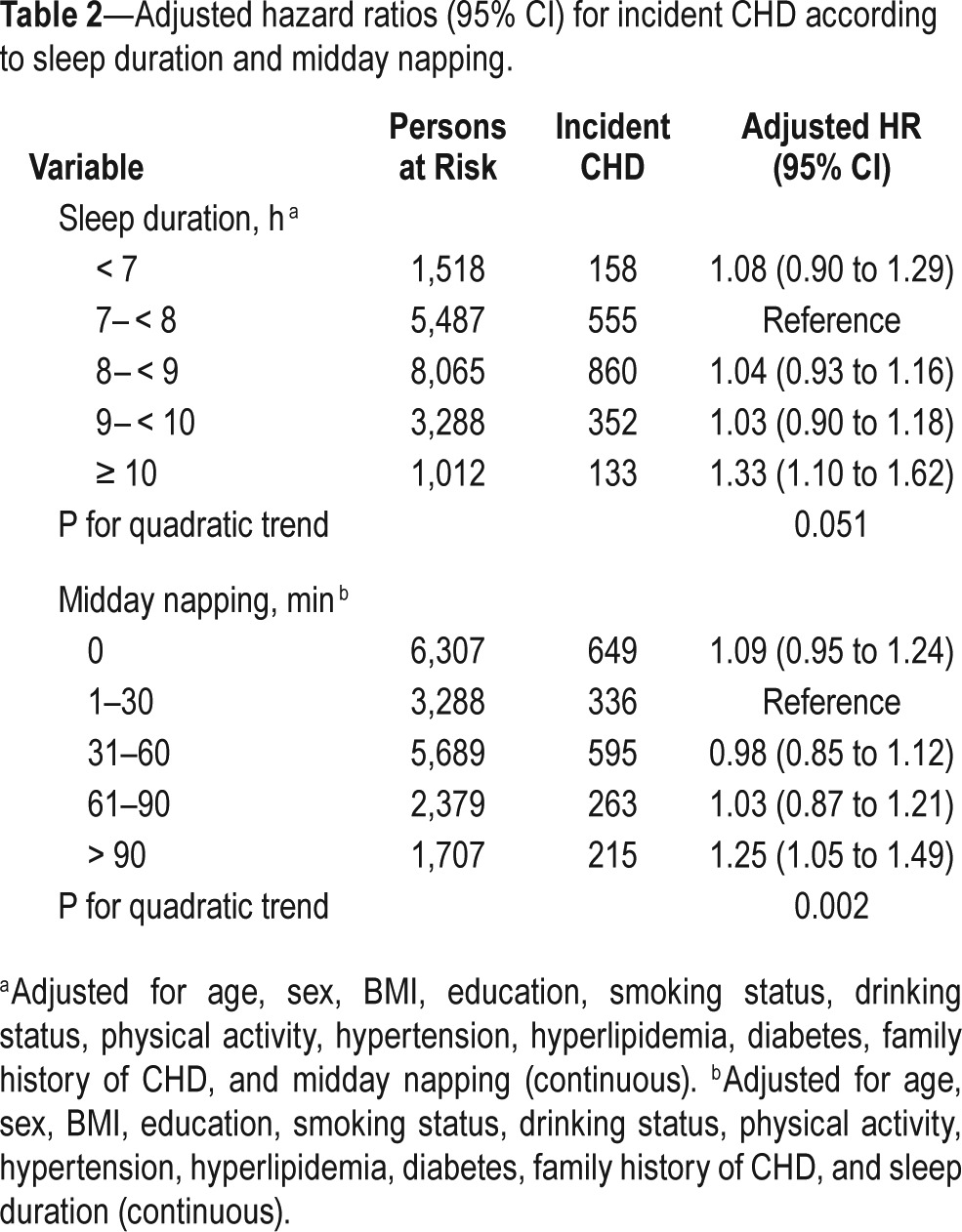

As shown in Table 2, after multivariate adjustment for potential confounders, we found that longer sleep duration and midday napping were independently associated with a higher risk of CHD incidence. Compared with the reference group, the multivariate-adjusted HR (95% CI) of CHD incidence was 1.33 (1.10 to 1.62) for sleeping ≥ 10 h/night, while other subgroups of sleep duration were weakly and not significantly associated with a higher risk of incident CHD (P for quadratic trend = 0.051). Similarly, those reported napping > 90 min were also at significantly increased risk of incident CHD (HR = 1.25; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.49; P for quadratic trend = 0.002), but the respective multivariable HR (95% CI) for those reported no napping, napping 31–60 min, and napping 61–90 min were 1.09 (0.95 to 1.24), 0.98 (0.85 to 1.12), and 1.03 (0.87 to 1.21), respectively. Additional adjustment for triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol, and waist circumference as well as sleep quality at baseline attenuated the association slightly, but remained the significance of the relationship. The nonlinear associations of sleep duration and midday napping with incident CHD risk were further illustrated by the spline curve in Figure 3. Cubic spline regression confirmed the risk of CHD incidence may be higher with prolonged sleep duration and midday napping.

Table 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) for incident CHD according to sleep duration and midday napping.

Figure 3.

Multivariable adjusted spline curves for relation between sleep duration and midday napping with incident CHD. All covariates were age, sex, BMI, smoking status, drinking status, education, physical activity, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, family history of CHD, sleep duration, and midday napping. Each group adjusted for the other covariates except itself. The reference groups were 7 h for sleep duration and 30 min for midday napping.

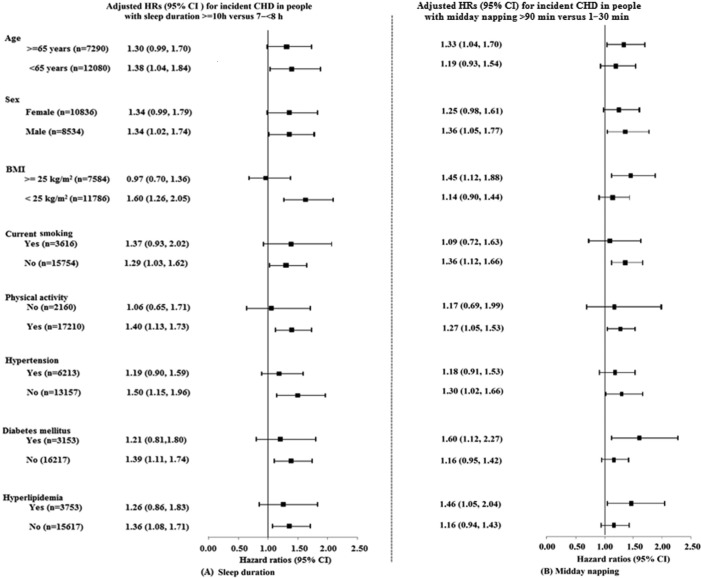

Stratification analyses showed that the association between longer sleep duration and CHD incidence was more pronounced in normal-weight individuals, and those without diabetes (P for interaction = 0.03 and 0.04, respectively; Figure 1 and Table S1 in the supplemental material), but there was a suggestion that this association was stronger in males and relative “healthy” individuals who were younger than 65 years of age, physically active, nonsmokers, and those without hypertension or hyper-lipidemia (all P for interaction > 0.05; Table S1). However, in terms of longer midday napping, the association with incident CHD was inconsistent and additionally significant among individuals ≥ 65 years of age, overweight, and those with diabetes or hyperlipidemia, but interaction was only found between midday napping and BMI (P for interaction < 0.01; Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Figure 1.

Adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) for incident CHD in individuals with (A) long sleep duration (≥ 10 h) and (B) long midday napping (> 90 min) compared with the reference groups. All covariates were age, sex, BMI, smoking status, drinking status, education, physical activity, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, family history of CHD, sleep duration, and midday napping. Each group adjusted for the other covariates except itself. The reference groups were 7– < 8 h for sleep duration and 1–30 min for midday napping.

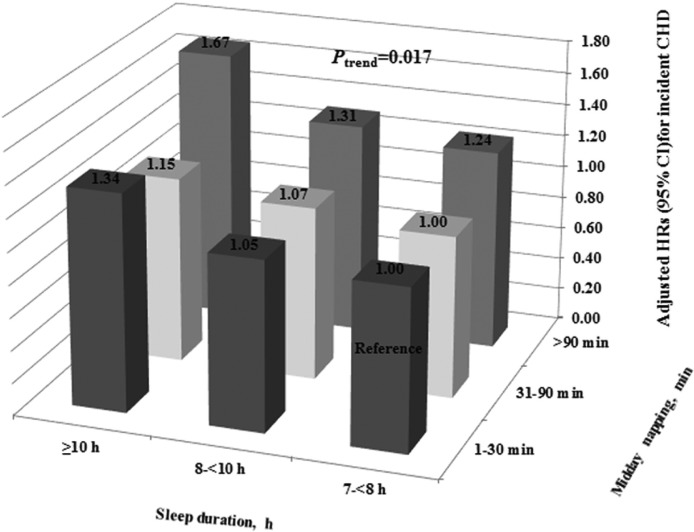

As sleep duration of 7– < 8 h and midday napping of 1–30 min were treated as the reference groups, we further analyzed the combined effect of sleep duration and midday napping on the risk of incident CHD among individuals with sleeping ≥ 7 h and napping > 0 min and those with sleeping < 7 h or no napping, respectively. Among individuals with sleeping ≥ 7 h and napping > 0 min, compared with participants reporting normal sleep duration (7– < 8 h) and appropriate midday napping (1–30 min), individuals with longer sleep duration (≥ 10 h) and longer midday napping (> 90 min) showed a 67% increased risk of incident CHD (HR = 1.67; 95% CI, 1.04 to 2.66; P for trend = 0.017; Figure 2); whereas among those with sleeping < 7 h or no napping, only those with sleep duration ≥ 10 h and no napping were at a higher risk of CHD incidence (HR = 1.60; 95% CI, 1.14 to 2.25; Table S3 in the supplemental material).

Figure 2.

Combined effects of sleep duration and midday napping on the risk of CHD incidence. All HRs were computed with normal sleep duration (7– < 8 h) and appropriate midday napping (1–30 min) as the reference group, with models adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking status, drinking status, education, physical activity, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and family history of CHD.

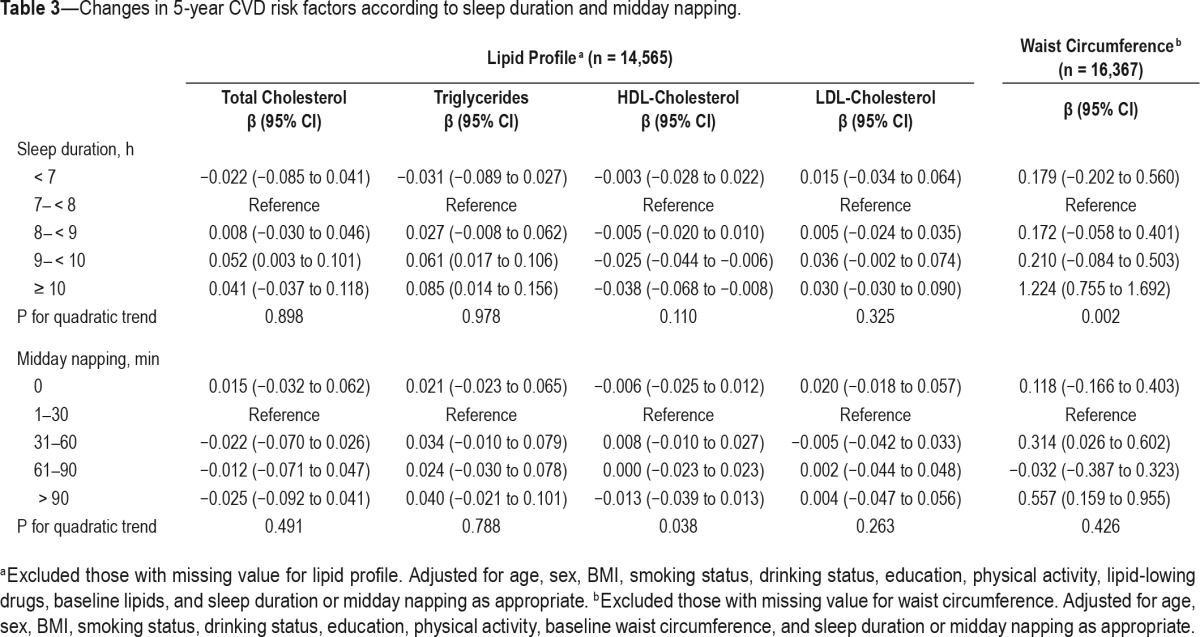

In terms of changes in CVD risk factors, longer sleep duration (≥ 10 h) was associated with significant increase in triglycerides (β = 0.085; 95% CI, 0.014 to 0.156), waist circumference (β = 1.224; 95% CI, 0.755 to 1.692), and decrease in HDL-cholesterol (β = −0.038; 95% CI, −0.068 to −0.008). Similarly, prolonged midday napping (> 90 min) was also related to significant increase in waist circumference (β = 0.557; 95% CI, 0.159 to 0.955) (Table 3). There was no significant association between longer sleep duration or midday napping with changes in BMI, blood pressure, or fasting glucose.

Table 3.

Changes in 5-year CVD risk factors according to sleep duration and midday napping.

DISCUSSION

The findings from this large prospective study indicated that longer sleep duration (≥ 10 h) and longer midday napping (> 90 min) were independently associated with increased risks of incident CHD, even after controlling for a variety of potential confounders. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to simultaneously investigate the relationship of sleep duration and midday napping with risk of CHD incidence in middle-aged and older Chinese adults. Several prospective studies have investigated the relationship between sleep duration and CHD incidence, but majority of them have shown an increased risk of CHD incidence among short sleepers.4–6,23 Our results have not found this relationship was due to the very small number of incident cases (n = 15) among individuals sleeping < 6 h, resulting in a limited statistical power. The finding of increased CHD risk with long sleep duration is largely consistent with an earlier study in the Nurses' Health Study, where long sleep duration of 9 h or more was associated with a 1.4-fold increased incidence of CHD in women aged 45 to 65 years.9 In our analyses, the risk of CHD incidence associated with sleep duration was significant in men, and marginally significant in women. A longer follow-up is needed to evaluate any sex-specific effects of long sleep duration on incident CHD, as previous studies suggested that disease status might affect sleep patterns during short follow-up periods.3 Due to reduced participation in physical or social activities, the elderly were more likely to go to bed earlier than younger adults. However, self-reported sleep duration was assessed by questionnaire, which did not allow us to differentiate time asleep from time in bed.

Interestingly, the above-mentioned association between longer sleep duration and increased incident CHD risk was more pronounced in individuals who were normal weight and without diabetes. Magee et al.24 previously showed that long or short sleep duration was significantly associated with an increased risk of heart disease only in adults aged < 65 years or non-smokers, but not in those older than 65 years or smokers, which is consistent with our finding. The results are also partly supported by a recent finding that long sleep was significantly associated with a higher stroke risk among those without preexisting diabetes or MI.25 Although the precise pathophysio-logical mechanisms underlying these characteristic variations are unclear, it is plausible that the effects of traditional CHD risk factors on CHD are so pronounced that it may mask the effect of longer sleep duration on CHD in high-risk individuals and leave the detrimental effects to be manifested in relatively healthy adults.24

Our data further revealed that prolonged midday napping was also an independent predictor of CHD incidence. Midday napping is common among older adults, and a short nap is beneficial since it may reduce subjective sleepiness and act as a stress-releasing habit.26,27 A case-control study in Greece found that nap of less than 30 min (known as power nap) was inversely associated with risk of acute CHD episodes.28 The current study indicated that excessive midday napping was associated with an increased risk of incident CHD. Our results were consistent with earlier studies that reported a positive association between midday napping and elevated risk of CHD incidence or mortality.13,29,30 In addition, an interesting finding in this study was the significantly combined effect of sleep duration and midday napping on the risk of incident CHD, which highlighted that both longer sleep duration and longer napping were associated with adverse health consequences and jointly predicted incident CHD. This preliminary finding on the relations of sleep duration and midday napping with incident CHD risk should be confirmed with future research.

Most of the previous studies on the association of sleep duration and midday napping with CHD did not include the corresponding changes in CVD risk factors. In contrast, we found that longer sleep duration and midday napping were closely related to unfavorable changes in triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol, or waist circumference, which are common predisposing factors for CHD. Therefore, the relationship between sleep duration or midday napping and CHD incidence could partially be explained by intermediate cardiovascular parameters. Kaneita et al.31 reported that both short and long sleep duration were related to a high triglyceride level or a low HDL cholesterol level among women. Meanwhile, Williams et al.32 found that the mean levels of HDL were the lowest for women sleeping ≥ 9 h compared with those sleeping for 8 h among normotensive women with type 2 diabetes using data from the Nurses' Health Study, which suggested that decreased HDL may contribute to the previously observed relationship between sleep duration and increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study indicated that middle-aged participants with long sleep had elevated risk of central obesity, while the older ones were at increased risk of raised triglycerides.33 It is widely accepted that raised triglycerides, decreased HDL-cholesterol, and higher waist circumference are strong risk factors for development of CHD, and may be intermediate steps linking long sleep duration or midday napping to incident CHD.34,35 Although the biological mechanisms underlying the associations between longer sleep duration/midday napping and incident CHD remain unclear, it is worth noting the physical inactivity of long sleepers or nap takers due to increased time in bed, which reduces energy expenditure, promotes obesity, and triggers a thrombotic effect by enhancing blood viscosity, fibrinolysis, and platelet aggregation.36,37 Other proposed mechanisms relating longer sleep duration and midday napping to CHD incidence involve depression, and sleep apnea.38,39 Additionally, long sleep duration may be an early symptom of disease and may precede clinical diagnoses, since it is possible that preexisting undiagnosed cardiovascular morbidity may affect sleeping patterns.

There are several limitations that need to be addressed in our study. Firstly, the sleep duration and midday napping were based on self-report data and were subject to measurement error and misclassification. Secondly, although a number of potential confounders were included in our analysis, we could not rule out the possibility of residual confounding as many factors could be associated with sleep duration. The lack of comprehensive information on sleep complaints, snore, and nap frequency and other residual confounding factors limit further investigation into the relationship. However, the strengths of our study are its large sample size, perspective design, and the ability to adjust for a wide range of confounders. It would reduce possible bias and chance, and provide sufficient statistical power for the analyses of exposure and diseases. Thirdly, the results of the present study are limited to middle-aged and older adults who are free of CVD and cancer, and therefore the findings may not be generalized to populations of all ages, different health conditions, or other ethnicities. Finally, the follow-up period of the current study was comparatively shorter than previous studies.

In conclusion, our findings are novel in demonstrating that longer sleep duration and midday napping are independently associated with higher risk of CHD incidence, and their combined effects may contribute to increased risk in middle-aged and older adults. The associations could be partially explained by changes in lipid profile and waist circumference. Our results suggest that regulating sleep duration and midday napping is particularly important for CHD prevention.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. This work was supported by the Natural National Scientific Foundation of China (81373093,81230069, and 81390542), 111 Project (No. B12004); and the Program for Changjiang Scholars; Innovative Research Team in University of Ministry of Education of China (No. IRT1246); China Medical Board (No.12-113). The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author contributions: L. Yang, X. Zhang had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: H. Yang, F. Hu, T. Wu, X. Zhang. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: L. Yang, X. Zhang. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: L. Yang, X. Zhang. Obtained funding: H. Yang, T. Wu, X. Zhang. Administrative, technical, or material support: X. Min, C. Zhang, C. Xu, M. He, A. Pan, S. Wei, X. Miao, J. Yuan. Study supervision: T. Wu, X. Zhang.

REFERENCES

- 1.Choi KM, Lee JS, Park HS, Baik SH, Choi DS, Kim SM. Relationship between sleep duration and the metabolic syndrome: Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey 2001. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1091–7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cappuccio FP, D'Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Quantity and quality of sleep and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:414–20. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cappuccio FP, Cooper D, D'Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1484–92. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meisinger C, Heier M, Lowel H, Schneider A, Doring A. Sleep duration and sleep complaints and risk of myocardial infarction in middle-aged men and women from the general population: the MONICA/KORA Augsburg cohort study. Sleep. 2007;30:1121–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amagai Y, Ishikawa S, Gotoh T, Kayaba K, Nakamura Y, Kajii E. Sleep duration and incidence of cardiovascular events in a Japanese population: the Jichi Medical School cohort study. J Epidemiol. 2010;20:106–10. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20090053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoevenaar-Blom MP, Spijkerman AM, Kromhout D, van den Berg JF, Verschuren WM. Sleep duration and sleep quality in relation to 12-year cardiovascular disease incidence: the MORGEN study. Sleep. 2011;34:1487–92. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tamakoshi A, Ohno Y. Self-reported sleep duration as a predictor of all-cause mortality: results from the JACC study, Japan. Sleep. 2004;27:51–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao Q, Keadle SK, Hollenbeck AR, Matthews CE. Sleep duration and total and cause-specific mortality in a large US cohort: interrelationships with physical activity, sedentary behavior, and body mass index. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180:997–1006. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayas NT, White DP, Manson JE, et al. A prospective study of sleep duration and coronary heart disease in women. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:205–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shankar A, Koh WP, Yuan JM, Lee HP, Yu MC. Sleep duration and coronary heart disease mortality among Chinese adults in Singapore: a population-based cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:1367–73. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikehara S, Iso H, Date C, et al. Association of sleep duration with mortality from cardiovascular disease and other causes for Japanese men and women: the JACC study. Sleep. 2009;32:295–301. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lan TY, Lan TH, Wen CP, Lin YH, Chuang YL. Nighttime sleep, Chinese afternoon nap, and mortality in the elderly. Sleep. 2007;30:1105–10. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stang A, Dragano N, Moebus S, et al. Midday naps and the risk of coronary artery disease: results of the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. Sleep. 2012;35:1705–12. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang F, Zhu J, Yao P, et al. Cohort Profile: the Dongfeng-Tongji cohort study of retired workers. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:731–40. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nomenclature and criteria for diagnosis of ischemic heart disease. Report of the Joint International Society and Federation of Cardiology/World Health Organization task force on standardization of clinical nomenclature. Circulation. 1979;59:607–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.59.3.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Preis SR, Hwang SJ, Coady S, et al. Trends in all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality among women and men with and without diabetes mellitus in the Framingham Heart Study, 1950 to 2005. Circulation. 2009;119:1728–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.829176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adams HP, Jr., Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993;24:35–41. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cannon CP, Battler A, Brindis RG, et al. American College of Cardiology key data elements and definitions for measuring the clinical management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes. A report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Acute Coronary Syndromes Writing Committee) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:2114–30. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01702-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. 9th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1977. International classification of diseases. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. 10th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1990. International classification of diseases. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel SR, Ayas NT, Malhotra MR, et al. A prospective study of sleep duration and mortality risk in women. Sleep. 2004;27:440–4. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamaki M, Shirota A, Hayashi M, Hori T. Restorative effects of a short afternoon nap (< 30 min) in the elderly on subjective mood, performance and eeg activity. Sleep Res Online. 2000;3:131–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu J, Yuen J, Kang S. Sleep duration, C-reactive protein and risk of incident coronary heart disease--results from the Framingham Offspring Study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24:600–5. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magee CA, Kritharides L, Attia J, McElduff P, Banks E. Short and long sleep duration are associated with prevalent cardiovascular disease in Australian adults. J Sleep Res. 2012;21:441–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leng Y, Cappuccio FP, Wainwright NW, et al. Sleep duration and risk of fatal and nonfatal stroke: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2015;84:1072–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milner CE, Cote KA. Benefits of napping in healthy adults: impact of nap length, time of day, age, and experience with napping. J Sleep Res. 2009;18:272–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramachandruni S, Handberg E, Sheps DS. Acute and chronic psychological stress in coronary disease. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19:494–9. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000132321.24004.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trichopoulos D, Tzonou A, Christopoulos C, Havatzoglou S, Trichopoulou A. Does a siesta protect from coronary heart disease? Lancet. 1987;2:269–70. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90848-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanabe N, Iso H, Seki N, et al. Daytime napping and mortality, with a special reference to cardiovascular disease: the JACC study. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:233–43. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leng Y, Wainwright NW, Cappuccio FP, et al. Daytime napping and the risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality: a 13-year follow-up of a British population. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179:1115–24. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaneita Y, Uchiyama M, Yoshiike N, Ohida T. Associations of usual sleep duration with serum lipid and lipoprotein levels. Sleep. 2008;31:645–52. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.5.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams CJ, Hu FB, Patel SR, Mantzoros CS. Sleep duration and snoring in relation to biomarkers of cardiovascular disease risk among women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1233–40. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arora T, Jiang CQ, Thomas GN, et al. Self-reported long total sleep duration is associated with metabolic syndrome: the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2317–9. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Araghi MH, Thomas GN, Taheri S. The potential impact of sleep duration on lipid biomarkers of cardiovascular disease. Clin Lipidol. 2012;7:443–53. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Theorell-Haglow J, Berglund L, Berne C, Lindberg E. Both habitual short sleepers and long sleepers are at greater risk of obesity: a population-based 10-year follow-up in women. Sleep Med. 2014;15:1204–11. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koenig W, Sund M, Doring A, Ernst E. Leisure-time physical activity but not work-related physical activity is associated with decreased plasma viscosity. Results from a large population sample. Circulation. 1997;95:335–41. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.2.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thrall G, Lane D, Carroll D, Lip GY. A systematic review of the effects of acute psychological stress and physical activity on haemorheology, coagulation, fibrinolysis and platelet reactivity: implications for the pathogenesis of acute coronary syndromes. Thromb Res. 2007;120:819–47. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel SR, Malhotra A, Gottlieb DJ, White DP, Hu FB. Correlates of long sleep duration. Sleep. 2006;29:881–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.7.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Querejeta Roca G, Redline S, Punjabi N, et al. Sleep apnea is associated with subclinical myocardial injury in the community. The ARIC-SHHS study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1460–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1572OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.