Abstract

Background:

Control of blood sugar, hypertension, and dyslipidemia are key factors in diabetes management. Cucurbita ficifolia (pumpkin) is a vegetable which has been used traditionally as a remedy for diabetes in Iran. In addition, consumption of probiotics may have beneficial effects on people with Type 2 diabetes. The aim of this study was an investigation of the effects of C. ficifolia and probiotic yogurt consumption alone or at the same time on blood glucose and serum lipids in diabetic patients.

Methods:

Eighty eligible participants randomly were assigned to four groups: 1 - green C. ficifolia (100 g); 2 - probiotic yogurt (150 g); 3 - C. ficifolia plus probiotic yogurt (100 g C. ficifolia plus 150 g yogurt); and 4 -control (dietary advice) for 8 weeks. Blood pressure, glycemic response, lipid profile, and high-sensitive C-reactive protein (hsCRP) were measured before and after the intervention.

Results:

Total cholesterol (TC) decreased significantly in yogurt and yogurt plus C. ficifolia groups (within groups P = 0.010, and P < 0.001, respectively). C. ficifolia plus yogurt consumption resulted in a decrease in triglyceride (TG) and an increase in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) (within groups P < 0.001 and P = 0.001, respectively). All interventions led to a significant decrease in blood sugar, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), hsCRP, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level within groups. Blood pressure decreased significantly in Cucurbita group and yogurt group (within groups P < 0.001, and P = 0.001 for systolic blood pressure [SBP] and P < 0.001, and P = 0.004 for diastolic blood pressure [DBP], respectively). All variables changed between groups significantly except LDL-C level.

Conclusions:

Variables including TG, HDL-C, TC, fasting blood sugar, HbA1c, SBP, DBP, and hsCRP changed beneficially between groups. It seems that consumption of C. ficifolia and probiotic yogurt may help treatment of diabetic patients.

Keywords: Glycemic response, inflammatory marker, lipid profile, probiotic yogurt, pumpkin, Type 2 diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a chronic disease caused by insulin resistance and consequent decline in peripheral glucose uptake. Sedentary lifestyle, obesity, and unhealthy dietary behaviors are the most common risk factors of T2DM.[1] It was estimated that diabetes prevalence was 4% in 2010 and was expected to reach 5.4% by 2025.[2] The burden of T2DM is predicted to double in the near future. Approximately, 7.7% or 2 million adults suffer from diabetes in Iran. Diabetes prevalence has been reported 7% and 8% in Isfahan and Tehran provinces, respectively.[3] T2DM leads to serious complications such as nervous system disorders, kidney diseases, and eye problems, thus its prevention and treatment should be considered an urgent priority.[4] Medicinal plants have been used in the treatment of this disease as a supplementary method. There are more than 800 plants that have been utilized as an experimental treatment for DM. Their active compounds that have hypoglycemic effects included mucilage gum, glycans, flavonoids, triterpenes, and alkaloids. One of these plants that has been used traditionally in Asia is Cucurbita ficifolia (Cucurbitaceae) popularly known as pumpkin.[5,6] Initial investigations indicated that C. ficifolia may reduce blood glucose and lipid profile and improve glucose tolerance.[7] However, the mechanism of anti-diabetic action of this vegetable is unknown. Probiotic foods have live organisms which are beneficial for health. There are some evidences that probiotic foods consumption or supplementation might reduce serum cholesterol level and improve insulin sensitivity.[8] Some studies have evaluated the favorable health effects of probiotic dairy products. They showed that probiotic yogurt had a beneficial effect on metabolic factors and health cardiovascular health parameters.[9,10,11,12]

Since, there is little information regarding the effects of C. ficifolia and probiotic foods on blood glucose levels in humans, the goal of this study was to determine the effects of C. ficifolia and/or probiotic yogurt consumption on glycemic control, lipid profile, and inflammatory markers in Type 2 diabetic patients.

METHODS

Study design and participants

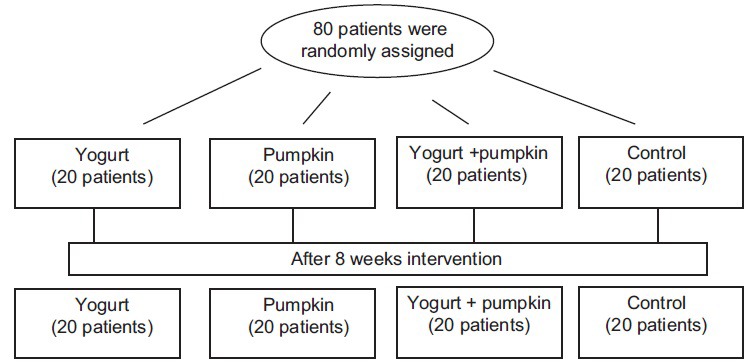

We conducted a parallel-group randomized controlled clinical trial. Type 2 diabetic patients were recruited from the Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Center, Isfahan. Eligibility criteria were age between 25 and 75 years, fasting blood sugar (FBS) more than 126 mg/dL, and controlled blood lipid without changing the drug instruction. All participants had to be no-smokers, take metformin or glibenclamide to control blood sugar, and not to drink any kinds of alcoholic beverages. Patients were excluded if they had a history of chronic illnesses such as renal, liver, pulmonary, and heart diseases or pancreatitis, endocarditis, short bowel syndrome, and allergy. None of the participants had autoimmune disorders were pregnant or lactating mothers. Totally, 80 Type 2 diabetic patients were selected and asked to participate in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, and all participants completed an informed consent form. Flow chart of study participants was shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study participants

Procedures

After enrollment, the subjects were randomly assigned to one of four dietary intervention arms lasting 8 weeks. During the intervention, subjects took one of following diets: (1) C. ficifolia (100 g); (2) probiotic yogurt (150 g); (3) C. ficifolia and probiotic yogurt (100 g C. ficifolia plus 150 g yogurt); and (4) control (dietary advice). Patients were instructed on consuming C. ficifolia and yogurt at lunch. They were required to consume C. ficifolia. Subjects were asked not to change their dietary habits, physical activity level, or other lifestyle factors during the study. Dietary compliance was assessed by regular weekly contacts or text messages. We also took a 3-day diet recall to assure compliance and analyzed it with Nutrition-IV software, version 15 (First Databank, San Bruno, CA, USA). This clinical trial was registered at irct.ir with number IRCT2013041311763N7.

Laboratory analyses

Five milliliter of fasting blood samples were obtained at baseline and at the end of the study. Plasma and serum stored at −70°C for determination of glucose, lipids, and CRP. Total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and triacylglycerols were measured by autoanalyzer. The Friedewald equation was used to calculate low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C),[13] when plasma triglyceride (TG) concentration was <400 mg/dL. Blood glucose (glucose oxidase method)[14] and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) were determined by an autoanalyzer. Serum concentrations of high sensitive C-reactive protein (hsCRP) were determined by immune turbidimetric using PARS AZMOON kit.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative variables have been reported as mean ± standard deviation, and qualitative variables as frequency (percent). Normality of variables was evaluated using K-S test or P-P plot. For nonnormal variables, log transformation was used. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Chi-square were used to assess baseline differences among the groups. Paired t-test was used to evaluate the difference between baseline and final values. Further analyses were conducted to investigate the between-group comparisons using multivariate ANOVA or multivariate analysis of covariance as appropriate. Bonferroni post hoc test was used for pairwise comparisons. The value P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant level. Analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

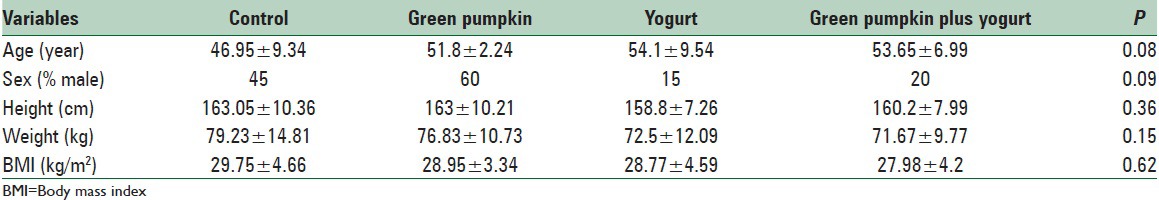

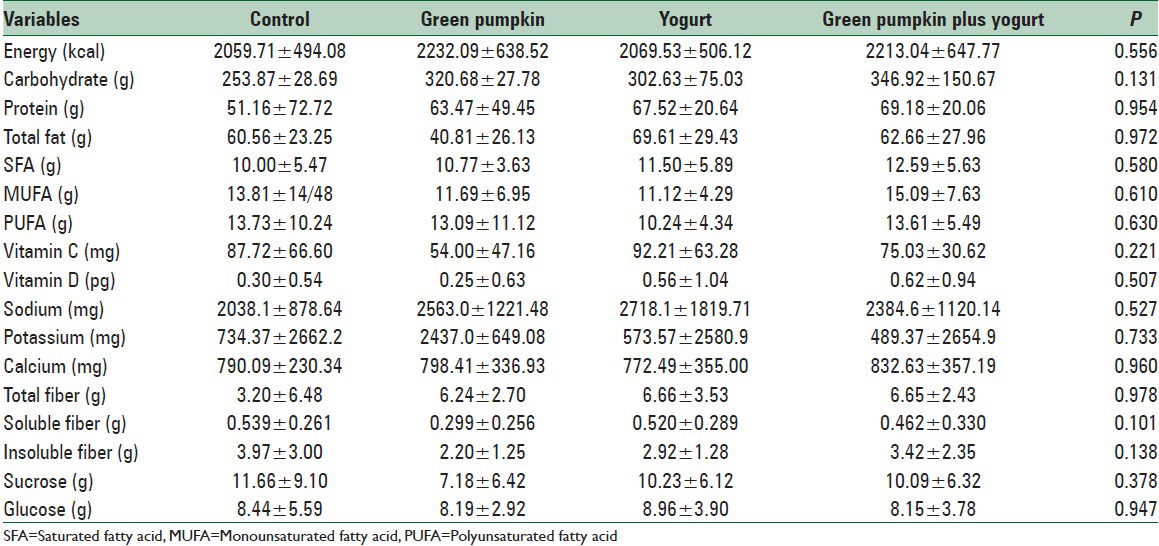

All 80 subjects completed the study (28.4 ± 2.9 y; body mass index, 23.1 ± 0.9 kg/m2). The characteristics of the patients showed no significant differences between groups [Table 1]. There was no significant difference between groups in total energy intake, macronutrient intake, and body weight at baseline. At the end of the study, no statistically significant differences between groups were observed for dietary intakes [Table 2]. Baseline values of biochemical measures were not different between groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in all groups

Table 2.

Comparison of nutrients intake in all groups of study

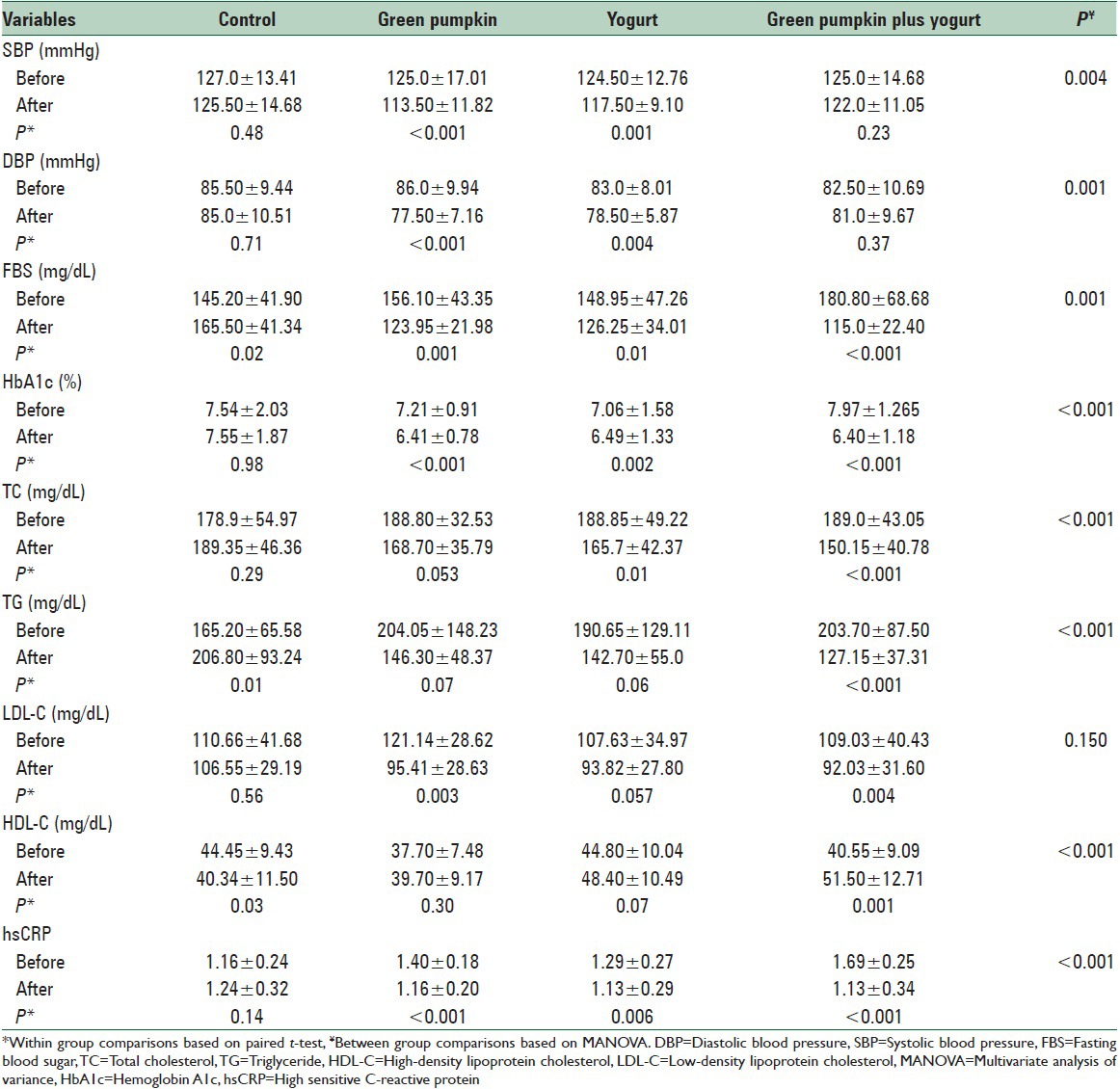

After 8 weeks, there were no significant changes in TC and LDL-C in the control group, but TG increased (P = 0.012), and HDL-C decreased (P = 0.034) significantly. In all intervention groups TC decreased, but it was significant only in yogurt and yogurt plus C. ficifolia groups (P = 0.010, and P < 0.001, respectively). TG declined, and HDL-C enhanced significantly in C. ficifolia plus yogurt group (P < 0.001and P = 0.001, respectively). Yogurt consumption decreased LDL-C significantly (P = 0.003 in yogurt and P = 0.004 in C. ficifolia plus yogurt). All changes were significant between groups (P < 0.001) except for LDL-C.

All interventions significantly decreased FBS (P = 0.001 in pumpkin, P = 0.014 in yogurt, and P < 0.001in C. ficifolia plus yogurt) and HbA1c (P < 0.001in C. ficifolia, P = 0.002 in yogurt, and P = 0.000 in C. ficifolia plus yogurt) in comparison with control group (between group P, 0.001 and < 0.001, respectively). HsCRP showed a significant reduction in all intervention groups (P < 0.001) which was more significant in C. ficifolia and C. ficifolia plus yogurt groups compared with yogurt group. At the end of the study, a statistically significant difference was seen among groups in systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP). Blood pressure decreased in C. ficifolia group and yogurt group significantly (P < 0.001, and P = 0.001 for SBP and P < 0.001, and P = 0.004 for DBP, respectively) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin A1c, serum lipids, and high sensitive C-reactive protein at baseline and postintervention in the four groups

DISCUSSION

In patients with Type 2 diabetes, it appears that probiotic yogurt consumption may substantially influence TC, FBS, HbA1c, hsCRP, and blood pressure. C. ficifolia significantly decreased LDL-C, glycemic control, hsCRP, and blood pressure. The most favorable effects on lipid profile, FBS, HbA1c, and hsCRP were related to C. ficifolia plus probiotic yogurt.

A few studies on human have shown that probiotic foods may decline serum lipids and lipoproteins.[15,16,17] The only study which used probiotic yogurt showed that TC decreased in mild to moderate hyperlipidemic subjects, but the other components of lipid profile did not change.[16] In this study, C. ficifolia just decreased LDL-C but animal studies revealed that it may reduce TG and increase HDL-C too.[18,19,20] The most noticeable results were related to C. ficifolia plus yogurt, which decreased atherogenic lipids and lipoproteins and increased HDL-C. To the best of our knowledge, no study has evaluated the combination of these two foods. The amount of pectin in C. ficifolia is high which can increase bile salts excretion and lipoprotein lipase activity and consequently decrease serum lipid levels.[19] The mechanism by which probiotic yogurt cholesterol reduces cholesterol can be attributed to the removal of the cholesterol by assimilation, its incorporation into the cell membrane, deconjugating bile acids,[21] and inhibition of hydroxy-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase (HMG-CoA reductase).[22]

The results of the study in the subjects with Type 2 diabetes indicated that yogurt and C. ficifolia alone or in combination decreased FBS and HbA1c significantly. Previous studies in diabetic subjects and also rats have shown that blood glucose and insulin sensitivity improved after probiotic consumption.[23] This finding contrasts the report by Mazloom et al. which concluded the relationship between probiotic capsule intake and FBS and insulin level.[15] This study did not assess participants’ compliance that can confound the results. The positive effects of C. ficifolia on glycemic control, insulin sensitivity, and glucose tolerance were reported by other researchers in animal models.[15,24,25,26,27,28] This finding can be explained by C. ficifolia effects in terms of β-glucosidase α-amylase inhibition,[24] and pancreas function and insulin sensitivity improvement.[15,29] The amount of fiber in this vegetable is not enough to produce such a result,[24] but it might be related to D-chiro inositol.[18]

HsCRP decreased in all intervention groups significantly. Moroti et al., evaluated the effects of C. ficifolia consumption on diabetic rats and found a reduction in CRP.[23] They assumed that it dropped because of the flavonoid content of C. ficifolia. Hadisaputro et al. found similar findings with kefir consumption on interleukin (IL)-1 and -6.[30] However, Mazloom et al. results were nonsignificant for IL-6 reduction, and they reported an increase in CRP.[15] This inconsistency can be described by the fact that they used probiotic as a supplement in diabetic patients. The role of probiotic in inflammation reduction may possibly be associated with gut microflora modulation.[31,32]

In this study, yogurt and C. ficifolia intake relative to their combination reduced SBP and DBP. Agerholm-Larsen et al. showed that 8 weeks intake of probiotic milk products decreased SBP significantly in healthy obese and overweight people.[33] Daily ingestion of the probiotic dairy such as fermented milk can reduce blood pressure in the high normal to mild hypertensive subjects.[34] Probiotics produce angiotensin-converting enzyme peptides by microbial activity which can play a role in blood pressure reduction.[35] It has not yet been defined any special mechanism for blood pressure lowering effect of C. ficifolia. As oxidative stress can lead to an increase in peripheral vascular resistance and hypertension[36] and Cucurbita decreases lipid peroxidation index such as thiobarbituric acid reactive substances and malondialdehyde and increases glutathione activity,[18,27] this outcome can be partly explained. However, we could find no interpretation for the lack of impact of yogurt and C. ficifolia combination on blood pressure.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results suggest that probiotic yogurt and C. ficifolia alone or together have beneficial effects on lipid profile, glycemic control, inflammation, and blood pressure in Type 2 diabetic patients. Our data confirm that concomitant use of C. ficifolia and yogurt has more noteworthy results in comparison with their intake alone. Variables including TG, HDL-C, TC, FBS, HbA1c, SBP, DBP, and hsCRP changed beneficially between groups. It seems that consumption of C. ficifolia and probiotic yogurt may help treatment of diabetic patients. Conducting more research in this area seems necessary to elucidate mechanisms and other effects.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Isfahan University of medical sciences and Food Security Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Study project number: 392362).

REFERENCES

- 1.Kiencke S, Handschin R, von Dahlen R, Muser J, Brunner-Larocca HP, Schumann J, et al. Pre-clinical diabetic cardiomyopathy: Prevalence, screening, and outcome. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:951–7. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esteghamati A, Meysamie A, Khalilzadeh O, Rashidi A, Haghazali M, Asgari F, et al. Third national Surveillance of Risk Factors of Non-Communicable Diseases (SuRFNCD-2007) in Iran: Methods and results on prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, obesity, central obesity, and dyslipidemia. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:167. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lutale J, Thordarson H, Sanyiwa A, Mafwiri M, Vetvik K, Krohn J. Diabetic retinopathy prevalence and its association with microalbuminuria and other risk factors in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. JOECSA. 2013;15:263–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suksomboon N, Poolsup N, Boonkaew S, Suthisisang CC. Meta-analysis of the effect of herbal supplement on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137:1328–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao MU, Sreenivasulu M, Chengaiah B, Reddy KJ, Chetty CM. Herbal medicines for diabetes mellitus: A review. Int J PharmTech Res. 2010;2:1883–92. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quanhong L, Caili F, Yukui R, Guanghui H, Tongyi C. Effects of protein-bound polysaccharide isolated from pumpkin on insulin in diabetic rats. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2005;60:13–6. doi: 10.1007/s11130-005-2536-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asemi Z, Zare Z, Shakeri H, Sabihi SS, Esmaillzadeh A. Effect of multispecies probiotic supplements on metabolic profiles, hs-CRP, and oxidative stress in patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Nutr Metab. 2013;63:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000349922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mani-López E, Palou E, López-Malo A. Probiotic viability and storage stability of yogurts and fermented milks prepared with several mixtures of lactic acid bacteria. J Dairy Sci. 2014;97:2578–90. doi: 10.3168/jds.2013-7551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nabavi S, Rafraf M, Somi MH, Homayouni-Rad A, Asghari-Jafarabadi M. Effects of probiotic yogurt consumption on metabolic factors in individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Dairy Sci. 2014;97:7386–93. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-8500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruz AG, Castro WF, Faria JA, Lollo PC, Amaya-Farfán J, Freitas MQ, et al. Probiotic yogurts manufactured with increased glucose oxidase levels: Postacidification, proteolytic patterns, survival of probiotic microorganisms, production of organic acid and aroma compounds. J Dairy Sci. 2012;95:2261–9. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-4582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lollo PC, Morato PN, Moura CS, Almada CN, Felicio TL, Esmerino EA, et al. Hypertension parameters are attenuated by the continuous consumption of probiotic Minas cheese. Food Res Int. 2015;76:611–7. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kadish AH, Litle RL, Sternberg JC. A new and rapid method for the determination of glucose by measurement of rate of oxygen consumption. Clin Chem. 1968;14:116–31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazloom Z, Yousefinejad A, Dabbaghmanesh MH. Effect of probiotics on lipid profile, glycemic control, insulin action, oxidative stress, and inflammatory markers in patients with type 2 diabetes: A clinical trial. Iran J Med Sci. 2013;38:38–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ataei-Jafari A, Tahbaz F, Alavi-Majd H, Joodaki H. Comparison of the effect of a probiotic yogurt and ordinary yogurt on serum cholesterol levels in subjects with mild to moderate hypercholesterolemia. Iran J Diabetes Lipid Disord. 2005;4:48–3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moroti C, Magri LF, de Rezende Costa M, Cavallini DC, Sivieri K. Effect of the consumption of a new symbiotic shake on glycemia and cholesterol levels in elderly people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Lipids Health Dis. 2012;11:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-11-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Díaz-Flores M, Angeles-Mejia S, Baiza-Gutman LA, Medina-Navarro R, Hernández-Saavedra D, Ortega-Camarillo C, et al. Effect of an aqueous extract of Cucurbita ficifolia Bouché on the glutathione redox cycle in mice with STZ-induced diabetes. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;144:101–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kazemi S, Asgari S, Mshtaqyan S, Rafieian M, Mahzouni P. Pumpkin preventive effect on diabetic indices and histopathology of the pancreas in rats with alloxan diabetes. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2010;28:1108–117. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshinari O, Sato H, Igarashi K. Anti-diabetic effects of pumpkin and its components, trigonelline and nicotinic acid, on Goto-Kakizaki rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2009;73:1033–41. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lye HS, Kuan CY, Ewe JA, Fung WY, Liong MT. The improvement of hypertension by probiotics: Effects on cholesterol, diabetes, renin, and phytoestrogens. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10:3755–75. doi: 10.3390/ijms10093755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aggarwal J, Swami G, Kumar M. Probiotics and their effects on metabolic diseases: An update. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:173–7. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2012/5004.2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moroti C, Souza Magri LF, de Rezende Costa M, Cavallini DC, Sivieri K. Effect of the consumption of a new symbiotic shake on glycemia and cholesterol levels in elderly people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Lipids Health Dis. 2012;11:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-11-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Acosta-Patiño JL, Jiménez-Balderas E, Juárez-Oropeza MA, Díaz-Zagoya JC. Hypoglycemic action of Cucurbita ficifolia on type 2 diabetic patients with moderately high blood glucose levels. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;77:99–101. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alarcon-Aguilar FJ, Hernandez-Galicia E, Campos-Sepulveda AE, Xolalpa-Molina S, Rivas-Vilchis JF, Vazquez-Carrillo LI, et al. Evaluation of the hypoglycemic effect of Cucurbita ficifolia Bouché (Cucurbitaceae) in different experimental models. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;82:185–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang Z, Du Q. Glucose-lowering activity of novel tetrasaccharide glyceroglycolipids from the fruits of Cucurbita moschata. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:1001–3. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia T, Wang Q. Hypoglycaemic role of Cucurbita ficifolia (Cucurbitaceae) fruit extract in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Sci Food Agric. 2007;87:1753–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yadav M, Jain S, Tomar R, Prasad GB, Yadav H. Medicinal and biological potential of pumpkin: An updated review. Nutr Res Rev. 2010;23:184–90. doi: 10.1017/S0954422410000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kazemi S, Asgari S, Mshtaqyan S, Rafieian M, Shklabady R. Pumpkin preventive effect on serum lipid levels in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. Univ J Med Sci. 2011;9:1108–17. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hadisaputro S, Djokomoeljanto RR, Judiono, Soesatyo MH. The effects of oral plain kefir supplementation on proinflammatory cytokine properties of the hyperglycemia Wistar rats induced by streptozotocin. Acta Med Indones. 2012;44:100–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeppsson B, Mangell P, Thorlacius H. Use of probiotics as prophylaxis for postoperative infections. Nutrients. 2011;3:604–12. doi: 10.3390/nu3050604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isolauri E, Kirjavainen PV, Salminen S. Probiotics: A role in the treatment of intestinal infection and inflammation? Gut. 2002;50(Suppl 3):III54–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.suppl_3.iii54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agerholm-Larsen L, Raben A, Haulrik N, Hansen AS, Manders M, Astrup A. Effect of 8 week intake of probiotic milk products on risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54:288–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600937. HYPERLINK “http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10745279” . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lye HS, Kuan CY, Ewe JA, Fung WY, Liong MT. The improvement of hypertension by probiotics: Effects on cholesterol, diabetes, renin, and phytoestrogens. Int J Molec Sc. 2009;10:3755–75. doi: 10.3390/ijms10093755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gobbetti M, Ferranti P, Smacchi E, Goffredi F, Addeo F. Production of Angiotensin-I-converting-enzyme-inhibitory peptides in fermented milks started by Lactobacillus delbrueckiisubsp. bulgaricus SS1 and Lactococcus lactissubsp. cremoris FT. FT4 APPL ENVIRON MICROB. 2000;66:3898–904. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.9.3898-3904.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taniyama Y, Griendling KK. Reactive oxygen species in the vasculature molecular and cellular mechanisms. Hypertension. 2003;42:1075–81. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000100443.09293.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]