Abstract

Background:

Sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors represent a novel class of antidiabetic drugs. The reporting quality of the trials evaluating the efficacy of these agents for glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus has not been explored. Our aim was to assess the reporting quality of such randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and to identify the predictors of reporting quality.

Materials and Methods:

A systematic literature search was conducted for RCTs published till 12 June 2014. Two independent investigators carried out the searches and assessed the reporting quality on three parameters: Overall quality score (OQS) using Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 statement, Jadad score and intention to treat analysis. Inter-rater agreements were compared using Cohen's weighted kappa statistic. Multivariable linear regression analysis was used to identify the predictors.

Results:

Thirty-seven relevant RCTs were included in the present analysis. The median OQS was 17 with a range from 8 to 21. On Jadad scale, the median score was three with a range from 0 to 5. Complete details about allocation concealment and blinding were present in 21 and 10 studies respectively. Most studies lacked an elaborate discussion on trial limitations and generalizability. Among the factors identified as significantly associated with reporting quality were the publishing journal and region of conduct of RCT.

Conclusions:

The key methodological items remain poorly reported in most studies. Strategies like stricter adherence to CONSORT guidelines by journals, access to full trial protocols to gain valuable information and full collaboration among investigators and methodologists might prove helpful in improving the quality of published RCT reports.

Key words: Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials, diabetes mellitus, intention to treat, Jadad score, randomized controlled trials, sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM) refers to a group of common metabolic disorders having the common pathology of hyperglycemia. Over the last two decades, there has been a huge rise in worldwide prevalence of DM from an estimated 30 million cases in 1985–285 million in 2010 which is further expected to increase to >360 million by 2030.[1] The American Diabetes Association recommends pharmacological as well as nonpharmacological (medical nutrition therapy, physical exercise, diabetes self-management education and support etc.) approaches for diabetic control.[2] Various currently available classes of drugs include sulfonylureas, biguanides, thiazolidinediones, meglitinides, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, incretin analogs and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors. However, undesirable side-effects of existing drugs complexed with multiple pathophysiological factors involved impede the efforts to achieve glycemic goals in approximately two-third of the diabetic patients.[3] Thus, there is a desperate need for novel alternative treatment options.

Sodium glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors provide a novel therapeutic strategy to augment renal glucose excretion in type 2 diabetic patients.[4] A number of compounds belonging to this group have been discovered. Of these, canagliflozin, dapagliflozin and empagliflozin are approved by US Food and Drug Administration for use as monotherapy or adjunct to other oral antidiabetic drugs for the management of type 2 DM. Among other SGLT2 inhibitors undergoing various stages of development are remogliflozin, ipragliflozin, sergliflozin, luseogliflozin, tofogliflozin and desoxyrhaponticin.[4] The efficacy and safety of these agents for controlling hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes has been evaluated in several clinical trials and meta-analyses with some concerns like urogenital infections, cardiovascular events, bladder and breast cancers.[4,5,6]

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are accepted as “gold standard” in evidence-based medicine for establishing the effectiveness of any health care intervention.[7] Good quality RCTs are deemed essential for developing clinical practice guidelines, guiding journal peer review decisions, conducting unbiased meta-analyses and interpretation of evidence.[8] Usually, RCT report serves as the sole evidence to appraise the design, conduct and analysis of RCTs. However, in order to be reflective of the methodological quality of RCTs, the reports should be of good quality. To improve the reporting quality of published RCTs, the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement, an international consensus expert guideline was developed in 1996, and last updated in 2010.[9,10,11] The CONSORT is widely accepted in the field of clinical trials and is supported by an increasing number of healthcare journals and leading editorial organizations. The impact of using CONSORT statement on improving the reporting quality of RCTs has been assessed in several studies.[12,13,14]

Extensive literature search could not reveal any data on quality of reporting of RCTs on SGLT2 inhibitors for type 2 DM. Taking into account the accumulated evidence on efficacy of this class of drugs and nonuniform formal endorsement of CONSORT statement by various endocrinology journals, it was considered relevant to explore and quantify the quality of RCT reporting in this area. Hence, the present study was planned to assess the quality of published RCTs on SGLT2 inhibitors for type 2 diabetes with a special focus on key methodological items like randomization, allocation concealment, blinding and analysis according to intention to treat (ITT) principle. Also, we tried to identify the factors predicting the reporting quality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

A comprehensive and systematic literature search was conducted using Medline, Embase and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) from inception through June 2014 to identify relevant articles. The search was last updated on 12 June 2014. Our strategy included “SGLT2 inhibitors” and “trials.” Two investigators carried out the search independently. All the searches were subsequently combined to retrieve the relevant articles. Manual search was carried out through the reference sections of printed articles to identify any additional potential articles.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Randomized controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors for glycemic control in patients with type 2 DM were identified and included in the present analysis. RCTs with primary end points other than glycemic control in type 2 DM were not included. All other studies including observational, cohort, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic, drug-interaction, conference abstracts, and non-RCTs were excluded. Studies published in non-English languages were also excluded.

Assessment of reporting quality

Two independent investigators, blinded to each other's ratings, assessed the reporting quality of RCTs on the following parameters.

Overall quality score

The overall quality of reporting was rated using CONSORT 2010 statement.[11] An overall quality score (OQS) was assigned using 22 of the 25 items (Item no. 1a, 1b, 2–17, 19–22) from CONSORT checklist. A score of 1 was given for an item well reported and 0 if it was not reported or not clear. The total score for a study was obtained by summing the scores for individual items, with a maximum total score of 22.

Jadad score

The Jadad scale, also known as Oxford Quality Scoring system, was developed through standardized item reduction process in 1996.[15] This is a three item scale focusing on information pertaining to randomization, blinding and drop-outs. When the study is described as randomized and double blind, a score of one is given in each of the two categories. An additional one point is given if the methods are described in detail and appropriate while one point is deducted if the description of the method is missing or inappropriate. If the numbers and reasons of drop-outs in all the study groups are provided, one point is given. The total score obtained by summing the individual items ranges from 0 to 5; a score of ≥3 indicating high quality and ≤2 indicative of low quality.

Intention to treat analysis

Analysis according to the ITT principle was assessed separately due to its importance in avoiding bias and distortions of the effect estimates.[16] Different researchers may carry different meanings for ITT. In this study, we adopted the most common and strictest interpretation, that is inclusion of all randomly assigned patients in the analysis, regardless of whether they actually satisfied the entry criteria, the treatment actually received, and subsequent withdrawal or protocol deviations.[17,18]

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the studies, OQS, Jadad scores and ITT analysis were described by descriptive analysis. Chance-adjusted inter-rater agreements for literature search and RCT quality assessment were compared using Cohen's weighted kappa statistic. The agreement was judged as good if kappa ≥0.81, substantial for kappa 0.61–0.8, moderate for kappa 0.41–0.6, fair for kappa 0.21–0.4 and poor for kappa ≤0.2.[19] Multivariable linear regression analysis was conducted to identify the factors associated with reporting quality of RCTs using OQS and Jadad score as outcome variables.

RESULTS

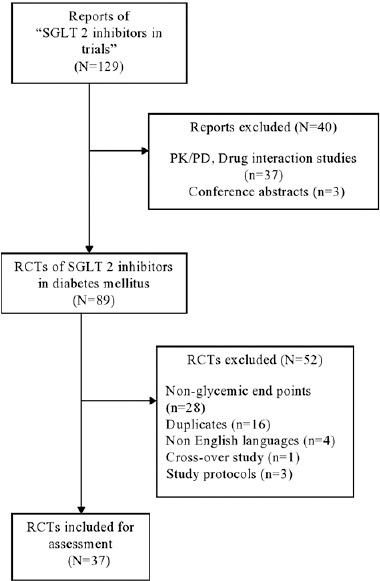

Figure 1 outlines the study selection process. Out of a total of 129 reports of “SGLT2 inhibitors in trials,” 89 RCTs of “SGLT2 inhibitors in DM” were identified. Further assessment of eligibility extracted 37 relevant RCTs for inclusion in the present analysis. The inter-rater agreement (kappa) between the two investigators for article selection was 0.89 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.83–0.95).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the article selection process

Characteristics of retrieved randomized controlled trials

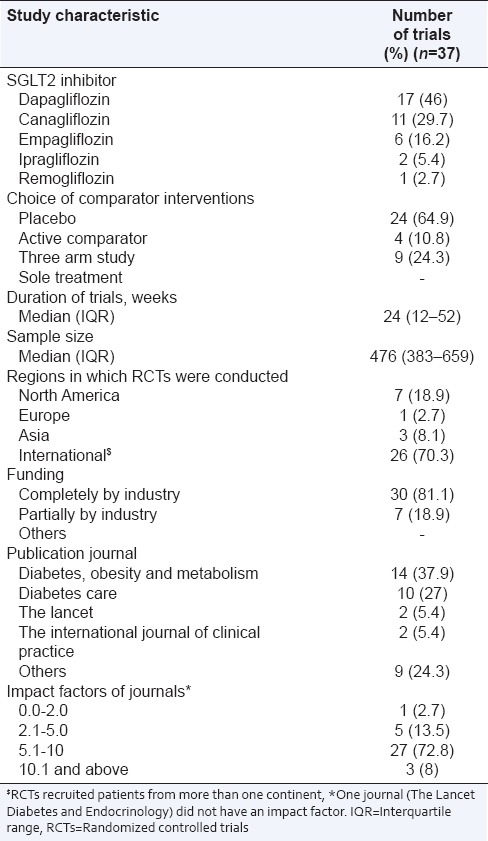

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of RCTs identified as relevant for the present study. Among the SGLT2 inhibitors, dapagliflozin and canagliflozin were studied in more than 70% trials. Most of the trials were placebo controlled. Around 70% trials recruited patients from more than one continent (International), while around 19% were conducted in North America. All the trials were funded by pharmaceutical industries with more than 80% receiving complete industrial funding. Most of the articles (65%) were published in “Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism” and “Diabetes Care” journals and maximum were published in journals with impact factors between 5 and 10.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

Quality of reporting

Overall quality score

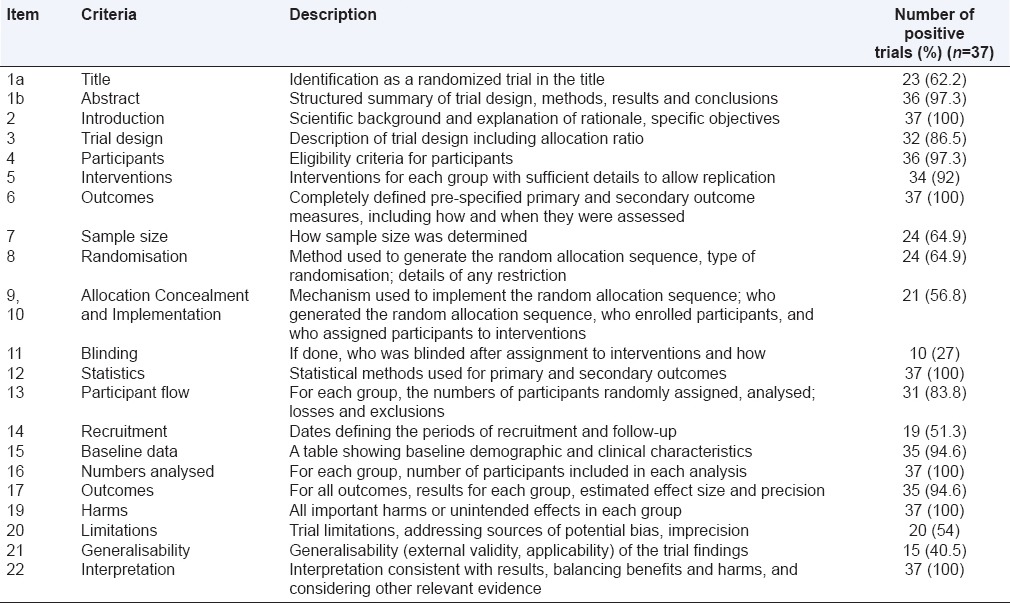

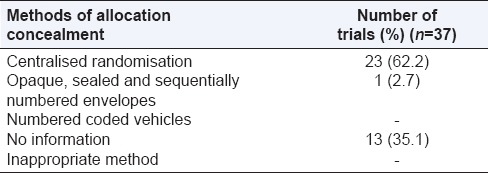

The rating of overall reporting using items from CONSORT checklist is shown in Table 2. The overall inter-rater agreement (kappa) for OQS was 0.72 (95% CI: 0.56–0.85). Most items were consistently well-reported in the majority of the studies although there was a suboptimal reporting for some key methodological items. Complete information on allocation concealment and implementation as per items 9 and 10 of CONSORT was provided in 21 studies while 24 studies described the methods of allocation concealment [Table 3]. Only 10 studies provided detailed and appropriate description of how blinding was assured while the blinded groups were mentioned in 16 studies [Table 4]. The dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up were given in around half of the studies. Six studies did not include the CONSORT flowchart in the main text. The discussion section of the majority of the articles lacked an explicit elaboration of the trial limitations and generalizability to external population. The median (interquartile range) OQS was 17 (14.5–19.5), with a minimum of 8 and maximum of 21.

Table 2.

Overall quality of reporting rating using items from CONSORT 2010 statement

Table 3.

The mechanisms of allocation concealment implemented in various trials

Table 4.

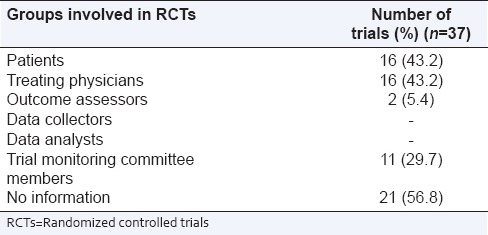

Blinded groups involved in RCTs

All but one trial provided information on registration while the source of funding was mentioned in all.

Jadad score

The median score on Jadad assessment tool was three, with a minimum and maximum of 0 and 5, respectively. The kappa inter-rater agreement for the score was 0.65 (95% CI: 0.46–0.84).

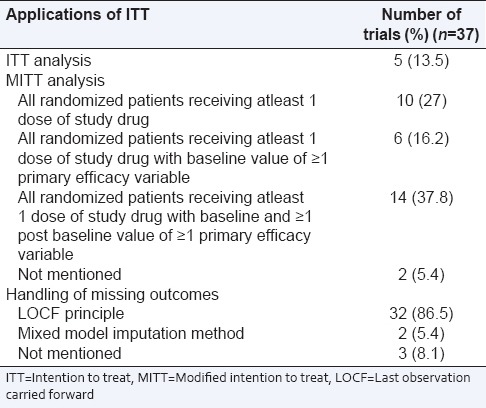

Intention to treat analysis

For ITT analysis, the value of kappa was 0.63 (95% CI: 0.41–0.82). Most of the studies carried out modified ITT analysis (30/37; 81%) and followed last observation carried forward principle for handling the missing data (32/37; 86.5%) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Specific applications of ITT

Factors associated with reporting quality

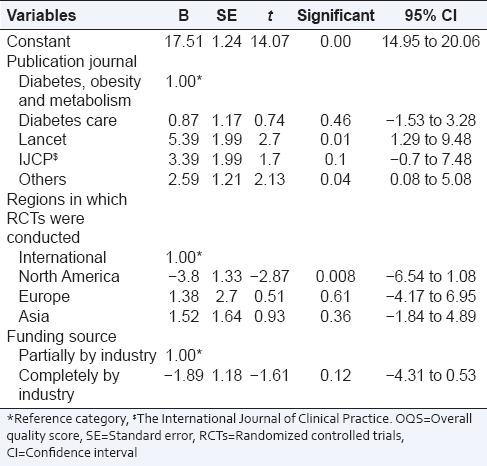

Overall quality score

The regression model shows that RCTs published in “Lancet” and other journals were significantly associated with an increase in OQS of 5.4 (95% CI: 1.28–9.48; P = 0.01) and 2.6 (95% CI: 0.08–5.08; P = 0.04), respectively compared to “diabetes, obesity and metabolism.” RCTs conducted in North America had an average score of 3.8 (95% CI: −6.54 to − 1.08; P = 0.008) less than those conducted internationally. Complete funding by industry was associated with a decrease in score by 1.9 (95% CI: −4.3–0.53) from partial industry funding, which was however statistically insignificant [Table 6].

Table 6.

Multivariable linear regression analysis for predictors of OQS using CONSORT statement (n=37)

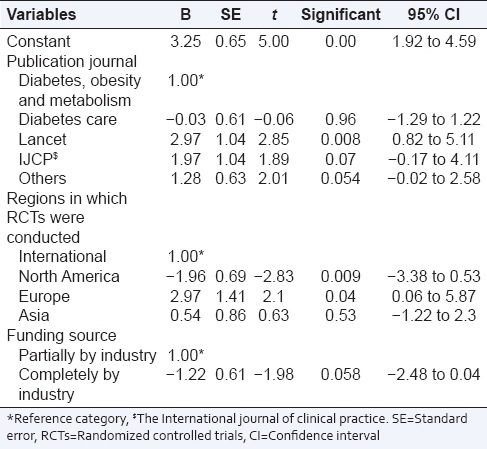

Jadad score

An increase in the score up to 3 (95% CI: 0.82–5.1; P = 0.008) was observed in RCTs published in “Lancet” when compared with “diabetes, obesity and metabolism.” On an average, RCTs conducted in North America and Europe had a score of two lower (95% CI: −3.38 to −0.53; P = 0.009) and 3 higher (95% CI: 0.06–5.87; P = 0.04), respectively, in contrast to international RCTs. Funding by industry had no statistically significant impact on Jadad score, although RCTs with complete funding from industry had a lesser score than those with partial funding [Table 7].

Table 7.

Multivariable linear regression analysis for predictors of Jadad score (n=37)

DISCUSSION

The findings of our study demonstrate that although most of the items on CONSORT checklist were appropriately reported in the majority of studies, the reporting quality of key methodological items was poor. Particularly, deficit information in areas like method of random sequence generation, allocation concealment mechanism and implementation of the whole randomization process was observed. Furthermore, how blinding was assured and the blinding status of groups who can potentially introduce bias was mentioned in few studies only. Allocation concealment and blinding are key safeguards against selection and performance/ascertainment biases. Lack of adequate reporting of these key items has been associated with distortions in estimates of the treatment effect and may potentially lead to erroneous conclusions.[8,16] Pertinent information on another key methodological item, that is, ITT analysis was, however, found to be adequate and most of the RCTs resorted to some modification in ITT analysis. Analysis according to ITT principle helps in avoiding attrition bias. Besides, the method for sample size determination was not reported in more than one-third trials, hence, the details regarding power of the study and whether the trial attained its planned size were not evident.

Among other not very consistently reported items were trial limitations and generalizability in the discussion section. Similar studies conducted previously did not rate the reporting of these subjective and qualitative items. In the present analysis, items related to clinical features like eligibility criteria, outcomes, baseline characteristics were however reported adequately in most studies. This finding indicates a greater importance and interest paid to clinical aspects particularly by clinician authors and a relative de-emphasis on methodological aspects, especially when article lengths are limited.

Our findings are in agreement with similar studies assessing the reporting qualities of RCTs published in various medical and surgical fields with the key methodological items being inconsistently reported most frequently.[20,21,22,23,24,25,26] In fact, the extent to which the quality of reports reflect the true methodological quality of RCTs is a matter of continuous debate and these are generally considered as surrogates of true quality of trials. For instance, Devereaux et al. observed that allocation concealment and blinding were frequently under-reported, but used appropriately in various RCTs.[27] However, contradictory evidence has also been furnished by few investigators who concluded that deficient reporting did reflect flawed methods.[28,29] Nevertheless, since the published reports are the major source for clinicians and researchers to judge the validity and generalizability of results, the importance of quality of reports cannot be under emphasized.

Reporting quality was better in publishing journals with high impact factors which may be explained by stricter peer review and higher scrutiny. Impact factor was however not identified as an influencing factor in regression analysis. On the contrary, reports published in “diabetes care” had poorer quality compared to many others from journals with lower impact factors. Although this journal endorses CONSORT statement, the information required is included in the supplementary online only file and not in the main article due to length constraints. Trials from outside of North America were better reported similar to a previous study.[25] Finally, trials partially funded by industry had better reporting quality than completely funded ones that was in contrast to similar previous studies.[20,25,30] Complex funding arrangements, generally not reported clearly can potentially introduce publication biases.[31,32,33]

Our study had some limitations. The RCT methodological quality was not directly verified from authors or their protocols due to the lack of direct access. Factors identified as associated with reporting quality may not fully explain variability in OQS and Jadad scores and stronger predictors like CONSORT endorsement by journals, author awareness of CONSORT statement and availability of advice from methodological expert at the time of planning of RCT could have been tested, which was however not within the scope of our study. Another limitation was the exclusion of crossover trials because CONSORT statement is applicable for parallel group designs only. Furthermore, our reporting quality scores are not validated, and none of the available reporting quality assessment tools have been validated. However, inter-rater agreement between the two investigators was good in our study demonstrating the reproducibility of the scoring. Despite the limitations, our study has highlighted some important areas which remain poorly addressed in RCT reports. Furthermore, our results had good internal validity due to a substantial degree of concordance beyond chance for most criteria between the two raters.

CONCLUSION

Inconsistent and suboptimal reporting of some key methodological items in RCT reports remains an area of concern. Hence, it is recommended that journals require even stricter adherence to the CONSORT guidelines. When restrictions on article length prevent, the inclusion of some important information as required by CONSORT checklist, access to the full trial protocol should be made at the journal website. Besides, full collaboration among clinicians, investigators, methodologists and statisticians is desirable at the time of manuscript preparation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Powers AC. Diabetes mellitus. In: Longo DL, Kasper DL, Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 8th ed. United States of America: The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc; 2012. pp. 2968–3003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:S14–80. doi: 10.2337/dc14-S014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Del Prato S, Felton AM, Munro N, Nesto R, Zimmet P, Zinman B, et al. Improving glucose management: Ten steps to get more patients with type 2 diabetes to glycaemic goal. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:1345–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thaddanee R, Khilnani AK, Khilnani G. SGLT-2 inhibitors: The glucosuric antidiabetics. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2013;2:347–52. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clar C, Gill JA, Court R, Waugh N. Systematic review of SGLT2 receptor inhibitors in dual or triple therapy in type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open. 2012;2 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M, Pagano G. A novel approach to control hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: Sodium glucose co-transport (SGLT) inhibitors: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Ann Med. 2012;44:375–93. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2011.560181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schünemann HJ, Jaeschke R, Cook DJ, Bria WF, El-Solh AA, Ernst A, et al. An official ATS statement: Grading the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in ATS guidelines and recommendations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:605–14. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-197ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Pham B, Jones A, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Moher M, et al. Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? Lancet. 1998;352:609–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01085-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276:637–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.8.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. CONSORT GROUP (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). The CONSORT statement: Revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:657–62. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:e1–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altman DG. Endorsement of the CONSORT statement by high impact medical journals: Survey of instructions for authors. BMJ. 2005;330:1056–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7499.1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plint AC, Moher D, Morrison A, Schulz K, Altman DG, Hill C, et al. Does the CONSORT checklist improve the quality of reports of randomised controlled trials? A systematic review. Med J Aust. 2006;185:263–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hopewell S, Altman DG, Moher D, Schulz KF. Endorsement of the CONSORT Statement by high impact factor medical journals: A survey of journal editors and journal ‘Instructions to Authors’. Trials. 2008;9:20. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA. 1995;273:408–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hollis S, Campbell F. What is meant by intention to treat analysis? Survey of published randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 1999;319:670–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lachin JM. Statistical considerations in the intent-to-treat principle. Control Clin Trials. 2000;21:167–89. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rios LP, Odueyungbo A, Moitri MO, Rahman MO, Thabane L. Quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials in general endocrinology literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3810–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scales CD, Jr, Norris RD, Keitz SA, Peterson BL, Preminger GM, Vieweg J, et al. A critical assessment of the quality of reporting of randomized, controlled trials in the urology literature. J Urol. 2007;177:1090–4. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farrokhyar F, Chu R, Whitlock R, Thabane L. A systematic review of the quality of publications reporting coronary artery bypass grafting trials. Can J Surg. 2007;50:266–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toulmonde M, Bellera C, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, Debled M, Bui B, Italiano A. Quality of randomized controlled trials reporting in the treatment of sarcomas. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1204–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.9369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinha S, Sinha S, Ashby E, Jayaram R, Grocott MP. Quality of reporting in randomized trials published in high-quality surgical journals. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:565–71.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Péron J, Pond GR, Gan HK, Chen EX, Almufti R, Maillet D, et al. Quality of reporting of modern randomized controlled trials in medical oncology: A systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:982–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen B, Liu J, Zhang C, Li M. A retrospective survey of quality of reporting on randomized controlled trials of metformin for polycystic ovary syndrome. Trials. 2014;15:128. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devereaux PJ, Choi PT, El-Dika S, Bhandari M, Montori VM, Schünemann HJ, et al. An observational study found that authors of randomized controlled trials frequently use concealment of randomization and blinding, despite the failure to report these methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:1232–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pildal J, Chan AW, Hróbjartsson A, Forfang E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC. Comparison of descriptions of allocation concealment in trial protocols and the published reports: Cohort study. BMJ. 2005;330:1049. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38414.422650.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liberati A, Himel HN, Chalmers TC. A quality assessment of randomized control trials of primary treatment of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4:942–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.6.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai R, Chu R, Fraumeni M, Thabane L. Quality of randomized controlled trials reporting in the primary treatment of brain tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1136–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Djulbegovic B, Lacevic M, Cantor A, Fields KK, Bennett CL, Adams JR, et al. The uncertainty principle and industry-sponsored research. Lancet. 2000;356:635–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02605-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, Matthews DR. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet. 1991;337:867–72. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90201-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH, Simms RW, Fortin PR, Felson DT, Minaker KL, et al. A study of manufacturer-supported trials of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of arthritis. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:157–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]