Abstract

Background:

Endothelial dysfunction probably has a role in the etiology of sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL). The aim of this study was determining of the relationship between endothelial dysfunction and SSNHL.

Materials and Methods:

In a case–control study, 30 patients with SSNHL and 30 otherwise healthy age and sex-matched controls were studied. Demographic data gathered included age, gender, family history of SSNHL, and history of smoking, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia. Laboratory data included measurement of hemoglobin, fasting blood sugar (FBS) and lipid profile. Endothelial function was assessed by measuring flow-mediated dilation (FMD).

Results:

The two groups were the same in age (47.9 ± 9.3 and 48.1 ± 9.6 years, P = 0.946) with female/male ratio of 1:1 in both groups. Diabetes and dyslipidemia were more frequent in patients than controls (20% vs. 0%, P = 0.024). Brachial artery diameter was greater in patients than controls before (4.24 ± 0.39 vs. 3.84 ± 0.23 mm, P < 0.001) and after ischemia (4.51 ± 0.43 vs. 4.28 ± 0.27 mm, P = 0.020), but FMD was lower in patients than controls (6.21 ± 3.0 vs. 11.52 ± 2.30%, P < 0.001). Binary logistic regression analysis showed that FMD was associated with SSNHL independent from FBS and lipid profile (odds ratio [95% confidence interval] =0.439 [0.260–0.740], P = 0.002).

Conclusion:

Endothelial dysfunction, among other cardiovascular risk factors, is associated with SSNHL. This association is independent from other cardiovascular risk factors including diabetes and dyslipidemia.

Key Words: Brachial artery diameter, endothelial dysfunction, sudden sensorineural hearing loss

INTRODUCTION

Sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL) refers to a condition in which a patient suddenly started hearing loss and the most common complications created when waking in the morning and progressive hearing loss occurs within 12 h or less. The patients have terrible feeling, so it is possible to imagine a life threatening disease and will end to profound hearing loss in both ears. Incidence of SSNHL 5–20 cases/100,000 in habitants in the Western countries is estimated. More than etiology for this disorder has been evaluated and treated for this reason it has been debated over many years. SSNHL is a syndrome and in the majority of cases the cause is idiopathic.[1]

Some studies have pointed to SSNHL associated with cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes and hypercholesterolemia, and another group of studies have pointed to investigate the causes of vascular disease and coagulopathy.[2] It is hypothesized that ear artery ischemia has a role in the development of SSNHL. Another group of studies have addressed the possible relationship between endothelial cell dysfunction in this disease. Even, SSNHL is proposed as an early warning signs of an impending attack of stroke. It has been suggested that SSNHL patients undergo in hematological and neurological studies to help facilitate identification that stroke is possible in the near future.[1]

Since studies have not yet established a clear picture of possible causes and on the other hand studies to investigate the possible role of endothelial dysfunction in this disease, the present study investigated endothelial dysfunction in patients with SSNHL as compared with otherwise healthy group.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and settings

This is a case–control study that was conducted in Kashani Hospital in Isfahan during 2012–2014. The target population included patients with SSNHL, who are admitted to this hospital and received 3 times injections into the tympanic membrane. Furthermore, a group of other patients were selected and studied in this hospital without any hearing related disease matched by age and sex. Inclusion criteria included approved diagnosis of SSNHL in patient group and patients without any illness associated with the auditory system in the control group, age range 25–70 years, no history of surgery on the ear, not suffering from congenital disorders of the auditory system and agreement of the individuals to participate in this study. Furthermore, if a case withdrew from cooperation or failure to perform required tests, the case was excluded from the study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and consent was obtained from participants. The required sample size was calculated using the formula of comparison of two means, considering study power of 80%, type I error of 0.05, and standard deviation (SD) of brachial vessels diameter as 1.1 mm, and the least expected difference between the two groups estimated as 0.8 mm. Sample size was estimated as 30 patients in each group.

Assessments

In this study, 30 patients were selected with proven diagnosis of SSNHL by the otolaryngologist confirmation, audiometry surveys, and other inclusion criteria. In the other hand for each patient in the case group, we chose and studied age and sex-matched controls among whom were referred to other clinics. At first, demographic data and general characteristics of the patients and controls were taken given specific checklist for this purpose. Blood samples were taken from the patients and controls and sent to the laboratory, the blood markers, including triglyceride, cholesterol, fasting blood sugar (FBS) were measured.

Flow-mediated dilation (FMD) was measured to assess the endothelial function. After participants rested for 10 min, brachial artery diameter was assessed using a high-resolution B-mode sonogram (ALOKA 5000 with 7.5 MHz transducer, Xinrui Science and Technology Limited, HongKong). The probe was placed at 5 cm above the anterior cubital cavity of the nondominant arm. Forearm ischemia was induced by inflating a sphygmomanometer cuff to 50–100 mmHg more than systolic blood pressure for 5 min. Brachial artery diameter before ischemia was assessed as baseline brachial artery diameter. 60 s after deflation the same assessment was done to measure the brachial artery diameter after ischemia. Measurement of arteries was performed during the diastolic phase. The FMD% was calculated according to the following formula 12; FMD % = ([maximum diameter − baseline diameter]/baseline diameter) × 100.[3]

Data analyzes

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows (Version 16.0, 2007, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented as mean ± SD or numbers (%). Normal distribution of quantitative data was checked with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Comparisons between the two groups were done using the Fisher's exact test for qualitative data and independent sample t-test (or Mann–Whitney U test) for quantitative data. Binary logistic regression model was conducted to test the relationship between endothelial function and SSNHL while controlling for other factors which was different between groups. Statistical significance was assessed at the 0.05 probability level in all analyzes.

RESULTS

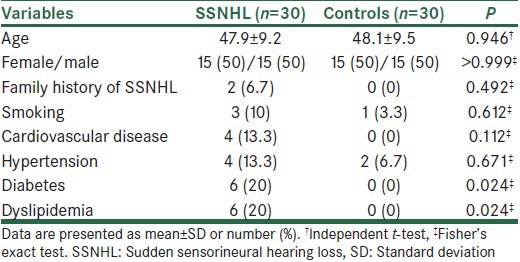

In this study, 30 patients with SSNHL and 30 normal subjects were studied. The mean ± SD of age in the case and control groups was 47.9 ± 9.3 and 48.1 ± 9.6 years, respectively (P = 0.946). The female/male ratio in both groups was 1:1. Only two subjects in the case group had a family history of SSNHL. Cardiovascular risk factors data in the case and control groups are shown in Table 1. Frequency of diabetes and dyslipidemia were significantly higher in patients than controls (P = 0.024).

Table 1.

Demographic data and cardiovascular risks in case and control groups

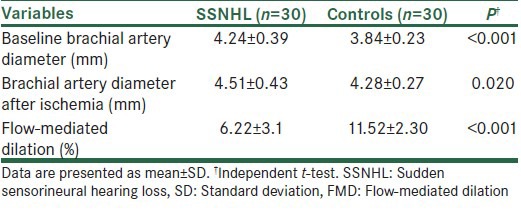

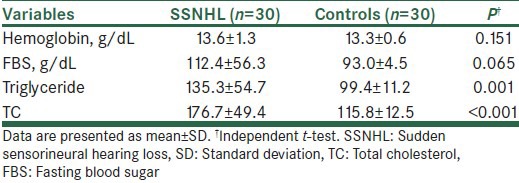

Endothelial function parameters are presented in Table 2. Brachial artery diameter was greater in patients than controls before (P < 0.001) and after ischemia (P = 0.020), but FMD was lower in patients than controls (P < 0.001). Laboratory data are presented in Table 3. Serum levels of triglycerides (P = 0.001) and total cholesterol (TC) (P < 0.001) were significantly higher in the patients than controls (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Brachial artery diameters and FMD in case and control groups

Table 3.

Laboratory data in the case and control groups

Considering differences between groups in lipid profile and cardiovascular risks, we conducted a binary logistic regression analysis to evaluate the relationship between FMD and SSNHL while controlling for FBS and the lipid profile (as current status of the patients). The results showed that FMD was associated with SSNHL independent from FBS and lipid profile (odds ratio [OR] [95% confidence interval (CI)] =0.439 [0.260–0.740], P = 0.002, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.836). TC was also independently associated with SSNHL (OR [95% CI] =1.104 [1.029–1.185], P = 0.006).

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was determining the relationship between SSNHL and endothelial dysfunction. In this study, 30 patients with SSNHL were compared with 30 normal subjects. Patient and control groups were matched in terms of age and sex together and thus neutralize the confounding effect of these factors in this study, and the results of the risk factors studied were affected. The prevalence of smoking, heart disease, and high blood pressure between the two groups was not significant, but diabetes and dyslipidemia were significantly more frequent in the patients than controls. Some other studies are pointed to the endothelial dysfunction leading to atherosclerosis.[4] Given the small number of patients and controls in our study cannot be a decisive influence on the incidence of SSNHL stated. However, diabetes and dyslipidemia in patients suspected of causing SSNHL should give importance to this issue. On the other, triglycerides and TC in patients with SSNHL were significantly higher than the controls and according to the results early endothelial dysfunction in patients with SSNHL might be affected. As the study by Aimoni et al. stated, cardiovascular risk factors including diabetes and hypercholesterolemia are associated with the risk of occurrence of SSNHL.[2] SSNHL incidence of vascular involvement is important assumptions.[5] In a study conducted by Mosnier et al., the theory of vascular disease as a cause of SSNHL was supported.[5] In a study that was conducted by Quaranta et al. also stated that endothelial progenitor cells, which are proliferated and differentiated into mature endothelial cells, are lower in patients with SSNHL. While we already know that these cells are reduced in patients with vascular risk factors, this study confirmed that endothelial dysfunction is involved in the creation of SSNHL and the presence of vascular damage in patients supported.[6]

In our study, the diameter of the brachial artery at rest and after ischemia was greater in patients than controls, but FMD was lower in patients than controls indicating endothelial dysfunction in patients compared with controls. Such association was independent from lipid profile and other cardiovascular risk factors. These results are similar to the results of the study of Celermajer et al.[4] The actual primary endothelial dysfunction leading to atherosclerosis, which ultimately leads to plaque. In a study of Celermajer et al., noninvasive method to detect endothelial function invented. By high-resolution ultrasonography of the brachial artery diameter at rest and after sublingual application trinitroglycerine (which causes the endothelium-dependent dilation) were measured. Basal diameter was inversely related to coronary vasodilatation.[4] Impaired endothelial dysfunction is a risk factor for atherosclerosis, such as smoking and hypercholesterolemia before the onset of plaque. Lin et al. assessed the risk of vascular disease after the onset of SSNHL. In this study, it was stated that SSNHL can be the early warning signal for the occurrence of stroke. It should SSNHL patients under hematologic and neurologic examinations for the diagnosis of patients who are at risk of stroke in the future.[7]

CONCLUSION

The results obtained in this study and comparison with other studies indicates that endothelial dysfunction, among other cardiovascular risk factors, is associated with SSNHL. This association is independent from other cardiovascular risk factors including diabetes and dyslipidemia. These results implicate that cardiovascular risk factors should be carefully evaluated in the management of patients with SSNHL.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arts HA. Sensorineural hearing loss in adults. In: Richardson MA, Flint PW, Haughey BH, Lund VJ, Niparko JK, Robbins KTh, et al., editors. Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. 5th ed. Ch. 149. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aimoni C, Bianchini C, Borin M, Ciorba A, Fellin R, Martini A, et al. Diabetes, cardiovascular risk factors and idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: A case-control study. Audiol Neurootol. 2010;15:111–5. doi: 10.1159/000231636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corretti MC, Anderson TJ, Benjamin EJ, Celermajer D, Charbonneau F, Creager MA, et al. Guidelines for the ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery: A report of the International Brachial Artery Reactivity Task Force. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:257–65. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01746-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Gooch VM, Spiegelhalter DJ, Miller OI, Sullivan ID, et al. Non-invasive detection of endothelial dysfunction in children and adults at risk of atherosclerosis. Lancet. 1992;340:1111–5. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93147-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosnier I, Stepanian A, Baron G, Bodenez C, Robier A, Meyer B, et al. Cardiovascular and thromboembolic risk factors in idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: A case-control study. Audiol Neurootol. 2011;16:55–66. doi: 10.1159/000312640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quaranta N, Ramunni A, De Luca C, Brescia P, Dambra P, De Tullio G, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells in sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Acta Otolaryngol. 2011;131:347–50. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2010.536990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin HC, Chao PZ, Lee HC. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss increases the risk of stroke: A 5-year follow-up study. Stroke. 2008;39:2744–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.519090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]