Abstract

The article discusses imiquimod treatment for refractory early stage mycosis fungoides, with a review of the literature and three case studies.

Keywords: Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, imiquimod, mycosis fungoides

Introduction

What was known?

Standard treatments for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma are super potent topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard surgery, and radiotherapy. For more extensive disease phototherapy, electron beam therapy, or systemic agents such as interferon alpha, bexarotene, or methotrexate can be used.

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most prevalent cutaneous lymphoma. MF is a difficult disease to treat, which is incurable and refractory to multiple treatments. Early stage patients present with patches and plaques in the skin and the disease may progress slowly over many years (10–15 years). Progression to an advanced stage with tumors, erythroderma, lymph node, or visceral involvement may occur with a poor prognosis. Skin-directed treatments are preferred in patients with early stage disease, but options are limited to topical corticosteroids, phototherapy, superficial radiotherapy, and nitrogen mustard preparations. Patients frequently reach maximal lifetime dose of phototherapy or radiotherapy or become refractory to the skin-directed therapy. Refractory early stage disease may require systemic therapies typically used for the advanced stages of MF such as bexarotene, interferon, gemcitabine, or multiagent chemotherapy. All these systemic therapies have significant adverse effects. Often treatments that worked initially lose their efficacy over time. Imiquimod is an immune response modifier that acts through Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7). Reports of activity in patches and plaques of MF are appearing in the literature. This article reviews the published literature and presents three cases of refractory MF treated with topical imiquimod.

Imiquimod

Imiquimod is a synthetic compound belonging to the imidazoquinoline family of compounds and a TLR agonist.[1] Imiquimod 5% (Aldara™) treats genital warts, superficial basal cell carcinomas, and actinic keratosis, but also used for lentigo maligna, hemangiomas, and molluscum contagiosum. Publications of use in MF have been single case reports[1,2,3,4,5,6,7] and four small cohort studies with 3–6 patients[8,9,10,11] [Table 1]. Chong's paper is the only randomized controlled trial with four patients, using the vehicle as control, and demonstrating an 8.9% decrease in surface area compared to a 39.9% increase in control patches and plaques.[9]

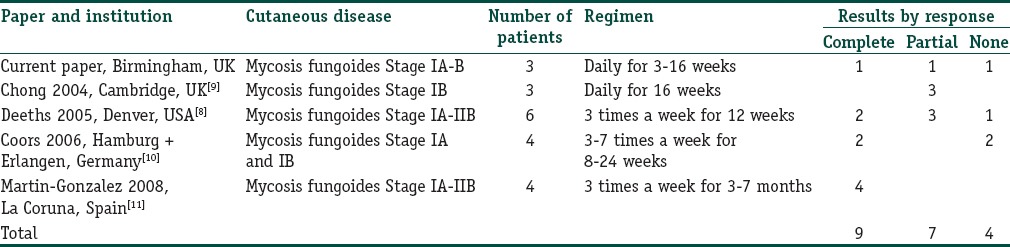

Table 1.

Case series’ reported results on the use of imiquimod 5% cream on mycosis fungoides

Imiquimod works by stimulating TLR7 resulting in cytokine release and inflammatory reaction. Interferon alpha production is increased, and the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 molecule is suppressed. Studies have demonstrated the recruitment of dendritic cells, CD8+ T cells, and natural killer cells. The pathogenesis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is being elucidated by genetic and molecular studies and includes derangements in the Bcl-2 pathway although the exact mechanism of imiquimod's action in cutaneous lymphoma is still unclear. Resiquimod is another imidazoquinolone, which activates TLRs 7 and 8 and is being investigated in phase 2 trials in actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.[12]

We present three patients with refractory 1A–1B MF and combine our cohort with published series [Table 1]. This gives an overall response rate to imiquimod of 80% (complete response in 9 of 20 patients [45%], partial response in 7/20 [35%]) with no response in 4/20 (20%).

Clinical Experience

A 61-year-old female presented with a 35 years history of refractory Stage IB MF [Figures 1 and 2]. Previous treatment included narrowband ultraviolet (UVB) B, psoralen and UVA, radiotherapy, electron beam therapy, topical nitrogen mustard 4%, clobetasone propionate 0.05%, interferon alpha (3 MU 3 times a week), and bexarotene 375 mg daily. Her treatment was complicated by multiple basal cell carcinomas and renal cell carcinoma in March 2014. Topical imiquimod, 5%, was initiated particularly concentrating on the genital area. Imiquimod was applied 5 days a week until clinical improvement, with regular 4 weekly outpatient appointments. A dramatic improvement was noted [Figure 3], the patient treated plaques on average for only 3 weeks to achieve prolonged (6 months) clearance, although treatment caused significant lethargy, aching, and flu-like symptoms. Histological clearance was demonstrated on repeat biopsy. Response was complete and durable at 9 months.

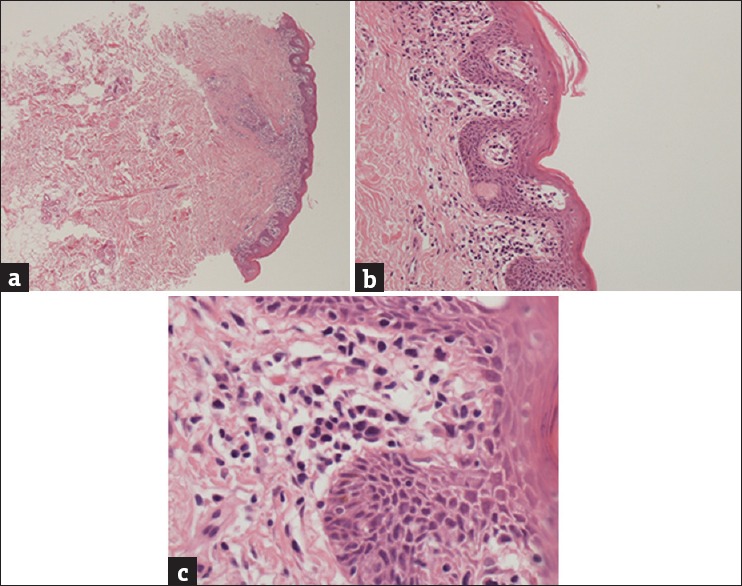

Figure 1.

Biopsy demonstrating dermal and follicular infiltrate (H and E, ×10) (a) with epidermotropism and Pautrier microabscess (H and E, ×40) (b) and mycosis fungoides cells with cerebriform nuclei (H and E, ×100) (c)

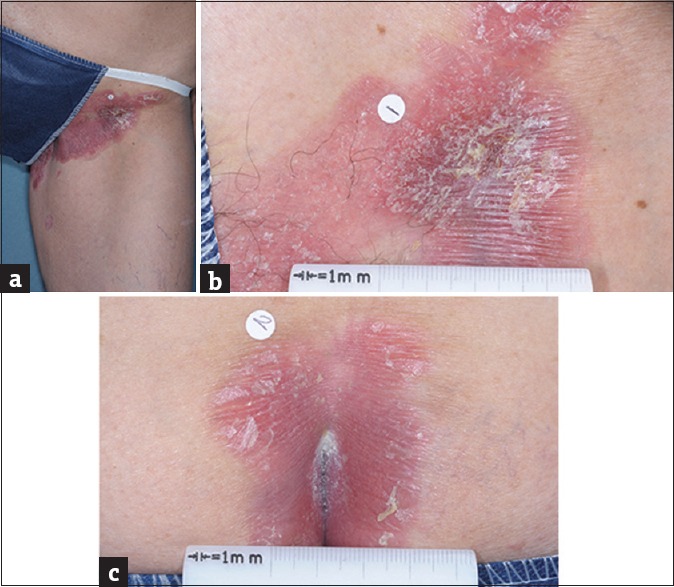

Figure 2.

Images of patient's mycosis fungoides on the left groin (a and b) and natal cleft (c)

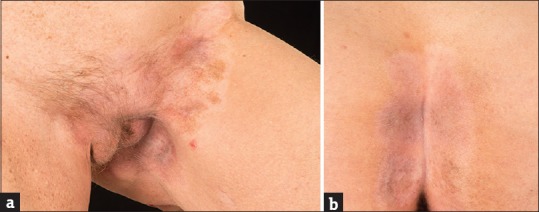

Figure 3.

Images of patient's mycosis fungoides after 3 weeks of topical imiquimod treatment showing left groin (a) and natal cleft (b)

The next patient is a 49-year-old man with a 3 years history of a fixed plaque on his left upper thigh, diagnosed histologically as MF, Stage IA. Previous treatment included clobetasone propionate 0.05% and tacrolimus 0.1% ointments with progressive disease in the skin. Imiquimod 5% was prescribed, daily, for 2 months and induced a significant inflammatory reaction but without clearance of the plaque. Response was a stable disease.

Our final patient is a 49-year-old man who received topical imiquimod, 5%, after having failed clobetasone propionate 0.05% ointment for the treatment of plaque Stage 1A MF. He was instructed to use the cream 5 times a week for 16 weeks. After just 5 weeks, he developed an acute inflammatory reaction and treatment was stopped. The skin healed within 4 weeks with a good response. Response was a partial response and durable over 6 months.

Conclusion

Early stage MF may have a long course over many years and skin-directed treatments are preferred, but these are limited in number and either maximal doses or loss of response typically occurs forcing the use of systemic therapies. Topical imiquimod 5% is an alternative topical agent for early stage refractory MF and may provide benefit in patients with plaques of MF resistant to other therapies. Similarly to use in basal cell carcinoma and actinic keratosis an inflammatory reaction occurs. However, the high response rate (80%) and possibility of durable complete responses in refractory disease make it a useful addition to our armoury.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What was new?

Topical imiquimod is a new option for treatment of refractory patches and plaques of MF.

References

- 1.Ariffin N, Khorshid M. Treatment of mycosis fungoides with imiquimod 5% cream. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:822–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suchin KR, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Rook AH. Treatment of stage IA cutaneous T-Cell lymphoma with topical application of the immune response modifier imiquimod. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1137–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.9.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiam LY, Chan YC. Solitary plaque mycosis fungoides on the penis responding to topical imiquimod therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:560–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soler-Machín J, Gilaberte-Calzada Y, Vera-Alvarez J, Coscojuela-Santaliestra C, Martínez-Morales J, Osán-Tello M. Imiquimod in treatment of palpebral mycosis fungoides. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2006;81:221–3. doi: 10.4321/s0365-66912006000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ardigò M, Cota C, Berardesca E. Unilesional mycosis fungoides successfully treated with imiquimod. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dummer R, Urosevic M, Kempf W, Kazakov D, Burg G. Imiquimod induces complete clearance of a PUVA-resistant plaque in mycosis fungoides. Dermatology. 2003;207:116–8. doi: 10.1159/000070962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Onsun N, Ufacik H, Kural Y, Topçu E, Somay A. Efficacy of imiquimod in solitary plaques of mycosis fungoides. Int J Tissue React. 2005;27:167–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deeths MJ, Chapman JT, Dellavalle RP, Zeng C, Aeling JL. Treatment of patch and plaque stage mycosis fungoides with imiquimod 5% cream. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:275–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chong A, Loo WJ, Banney L, Grant JW, Norris PG. Imiquimod 5% cream in the treatment of mycosis fungoides – A pilot study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:118–9. doi: 10.1080/09546630310019373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coors EA, Schuler G, Von Den Driesch P. Topical imiquimod as treatment for different kinds of cutaneous lymphoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:391–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martínez-González MC, Verea-Hernando MM, Yebra-Pimentel MT, Del Pozo J, Mazaira M, Fonseca E. Imiquimod in mycosis fungoides. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:148–52. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2008.0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer T, Surber C, French LE, Stockfleth E. Resiquimod, a topical drug for viral skin lesions and skin cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2013;22:149–59. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2013.749236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]