Abstract

Amelanotic melanoma (AMM) presenting as pyogenic granuloma and occurring in the vicinity of acquired melanocytic nevi is rare. Herein, we report such a manifestation in a 68-year-old male who presented with the painful red nodule and multiple pigmented patches involving the left great toe. Histopathological examination of skin biopsy taken from the nodule with an immunohistochemical study using HMB45 and S-100 confirmed the diagnosis of AMM. Biopsy from the pigmented patch near the nodule showed features of melanocytic nevus. Investigative work up revealed metastatic deposits in the left inguinal lymph node with no evidence of systemic involvement, placing him in malignant melanoma Stage IIIC of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor node metastasis system. The development of AMM in the vicinity of acquired melanocytic nevi and manifesting as granuloma pyogenicum is unique in this case.

Keywords: Amelanotic melanoma, HMB45, melanocytic nevi immunohistochemistry, pyogenic granuloma, S-100

Introduction

What was known?

Amelanotic melanoma is known to present with varied manifestations independent of melanocytic nevi.

Cutaneous malignant melanoma constitutes 4% of skin cancers and is responsible for 80% of skin cancer deaths.[1] A recent retrospective study conducted across Europe revealed that the incidence of melanoma is rapidly rising and predicted that it will continue to rise.[2] Cutaneous melanoma is characterized by varying amount of pigment within the tumor represented by shades of colors, including black, blue, pink, brown, and white. Red melanomas constitute 3.9% of all melanomas and 70% of all the amelanotic melanomas (AMM).[3] The term AMM is used for both true amelanotic lesion with no pigmentation and melanomas with minimal residual pigmentation.[4] Moreover, histologically true amelanotic malignant melanomas contain Stage I and Stage II melanosomes but not Stage III and Stage IV melanosomes.[5]

Case Report

A 68-year-old man presented with pigmented patches on the ball of left great toe of 6-year duration and red nodule over the left great toe for the last 6 months. He does not remember the evolution of the pigmented lesions and was not bothered as it was asymptomatic. However, he noticed a small nodule on the normal skin on the left great toe 6 months back following trauma, which on meddling resulted in bleeding. The nodule continued to grow to reach present size with recurrent episodes of bleeding and pain with no sign of healing. Cutaneous examination revealed red nodule on the medial aspect of left great toe, medial to the nail fold of size 2 × 1.5 cm, tender and bleeding on touch [Figure 1]. Multiple irregular jet black macules and patches spread on the plantar aspect of left great toe [Figure 2]. Single left inguinal lymph node was found enlarged, firm in consistency, and nontender. Systemic examination did not reveal any organ involvement. He was provisionally diagnosed as granuloma pyogenicum with acquired melanocytic nevi. However, malignant melanoma arising from agminated melanocytic nevi, hemangioma, melanoma, and deep mycosis were considered in the differential diagnosis and investigated. Routine blood chemistry, including blood sugar, blood urea, serum creatinine, liver function test, and serum lactic dehydrogenase (LDH), was normal. Serology for the human immune deficiency virus was nonreactive. Smear for fungus and culture on Sabouraud's dextrose agar was negative for fungus. Ultrasonography of the abdomen revealed normal study. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) from enlarged left inguinal lymphnode showed highly cellular smear with pleomorphic cells arranged in small clusters, groups, and individually scattered admixed with lymphocytes. Individual cells showed large pleomorphic centrally placed hyperchromatic nucleus with abundant cytoplasm. Some of the cells showed eccentrically placed nucleus and prominent nucleoli. Few binucleated cells were also seen [Figure 3]. Features were suggestive of secondary deposits in the lymph node. Biopsy was taken from both the erythematous nodule (specimen 1) and the pigmented patch (specimen 2) and were subjected to histopathological examination. Specimen 1 showed lobules of cuboidal cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and moderate amount of foamy cytoplasm, and few cells showed eccentric nuclei. There is mild to moderate pleomorphism and mitotic activity. Features were consistent with amelanotic malignant melanoma [Figures 4 and 5]. Immunohistochemistry with HMB45 and S-100 was strongly positive confirming the diagnosis of AMM [Figures 6 and 7]. Specimen 2 showed features of melanocytic nevus. The patient was finally diagnosed as AMM Stage IIIC (American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC] tumor node metastasis [TNM] system) with multiple acquired melanocytic nevi. Unfortunately, he was lost to follow-up while planning for treatment by a surgical oncologist.

Figure 1.

Erythematous nodule on the medial aspect of left great toe along with an ulcer, crusted plaque, and multiple pigmented macules on the plantar aspect

Figure 2.

Multiple irregular jet black macules on the plantar aspect of left great toe

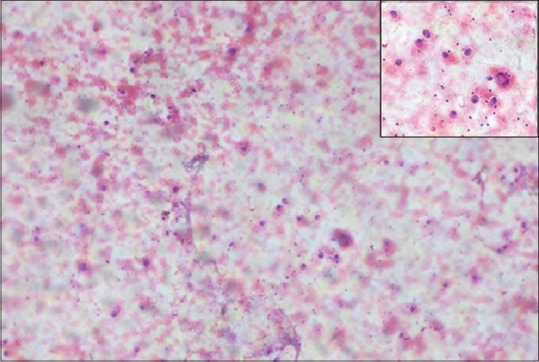

Figure 3.

Fine needle aspiration cytology (H and E) ×100 shows pleomorphic cells arranged in small clusters, groups, and individually scattered. Inset shows large pleomorphic centrally placed, hyperchromatic nucleus with abundant cytoplasm. Some of the cells showing eccentrically placed nucleus and prominent nucleoli. Few binucleated cells are also seen

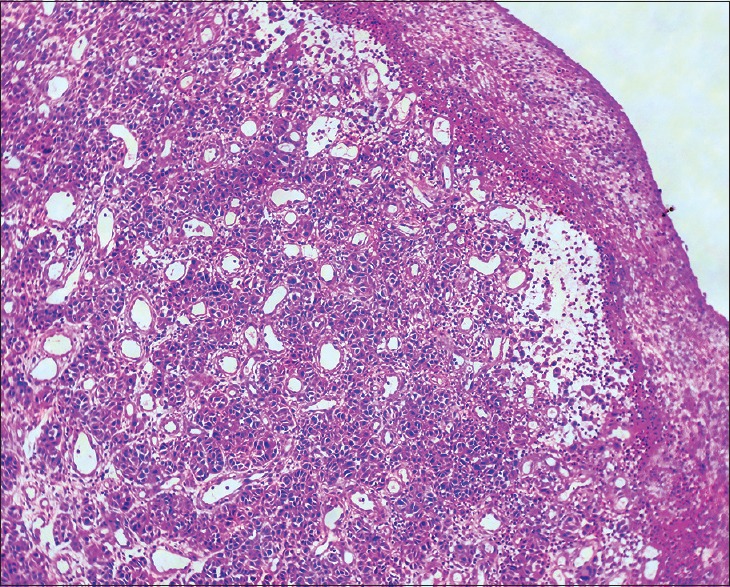

Figure 4.

Histopathology of skin H and E ×100. Dermis shows lobules of cuboidal cells with hyperchromatic nuclei with mild to moderate pleomorphism and mitotic activity

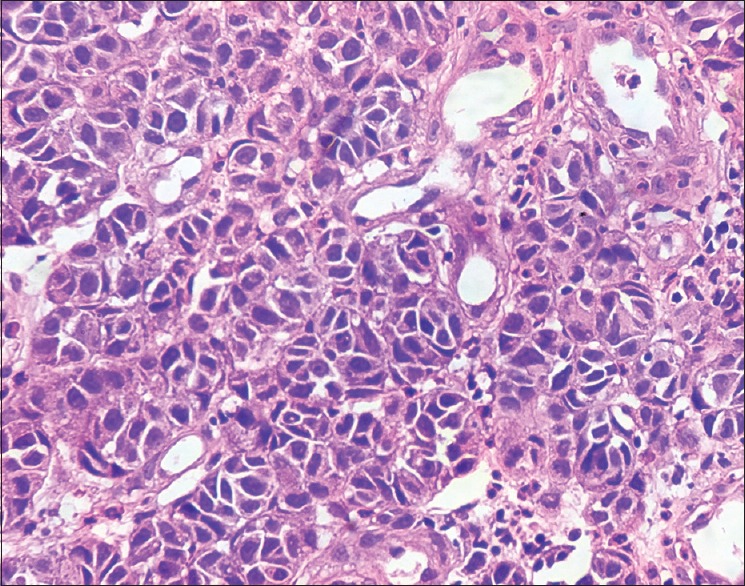

Figure 5.

Histopathology of skin H and E stain ×400. Cuboidal cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and moderate amount of foamy cytoplasm and few cells showing eccentric nuclei and pleomorphism and mitotic activity

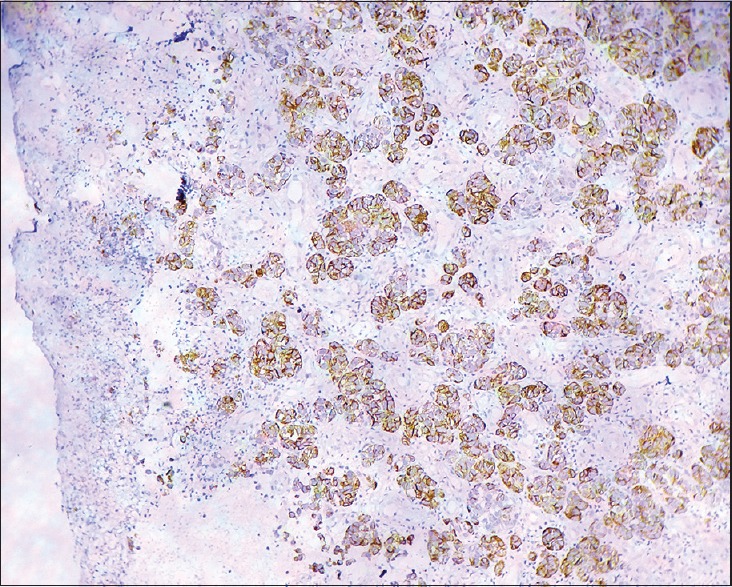

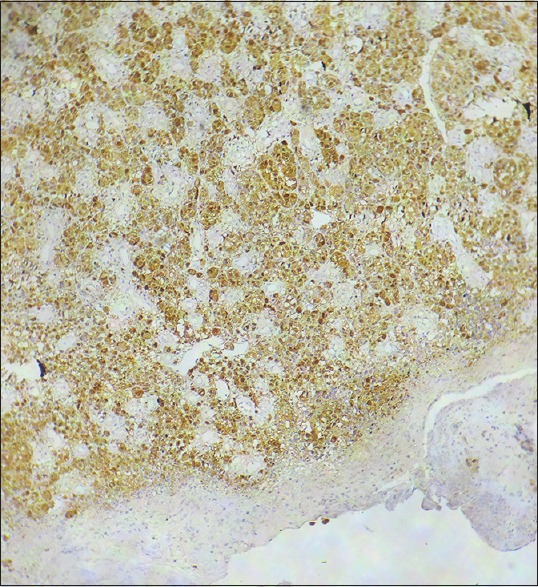

Figure 6.

Histopathology of skin ×100 Immunohistochemistry with HMB 45 showing strong positivity

Figure 7.

Histopathology of skin ×100 Immunohistochemistry with S-100 showing strong positivity

Discussion

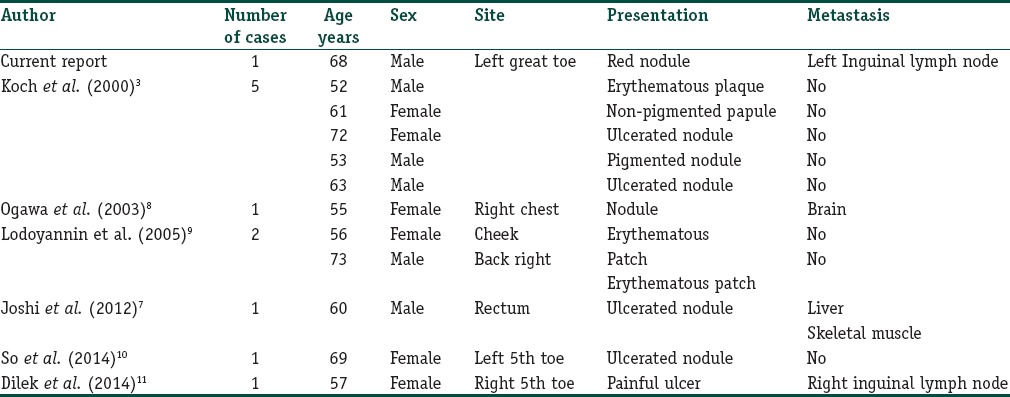

AMM account for 1.8-8.1% of all melanomas.[3] As the AMM do not produce pigment they mimic variety of benign and malignant tumors, which include melanocytic nevus, basal cell carcinoma, Bowen's disease, pyogenic granuloma, dermatofibroma, seborrheic keratosis, verruca vulgaris, actinic keratosis, and keratoacanthoma.[4,6] Notably, the case under study also presented as a pyogenic granuloma. Various morphological presentations of AMM have been reported in the literature, which include erythematous patch, plaque, nonpigmented papule, red nodule, ulcerated nodule, and paronychia[3,7,8,9,10,11] [Table 1]. Similarly, the index case also presented as erythematous nodule. AMM tends to occur on sun-exposed parts of the body.[12]

Table 1.

(Original) The morphological presentations of amelanotic melanoma by various authors

Interestingly, the AMM in the index case presented as granuloma pyogenicum with surrounding multiple melanocytic nevi. As the AMM is situated on the dorsum of the great toe, being a sun-exposed area, Ultraviolet (UV) radiation might have played a pivotal role in the causation of melanoma. On the contrary, the pigmented lesions (melanocytic nevi) on the plantar aspect, being sun-protected area did not show malignant changes, thus, vindicating the role of UV radiation in the etiology of melanoma. However, it is unclear, as to how AMM presented as granuloma pyogenicum and also spared nearby melanocytic nevi in the index case. In view of the presentation of AMM in the vicinity of melanocytic nevi, melanoma arising from agminated melanocytic nevi was considered in the index case. However, the patient denied history of presence pigmented patch in the area of melanoma and examination also did not show the presence of pigmented patch underneath the melanoma. Furthermore, histopathological examination of the nodule also did not reveal the presence of melanoma overlying the melanocytic nevus. Hence, the diagnosis of melanoma arising from agminated melanocytic nevi could not be entertained.

Notably, Clark proposed a model for the development of melanoma in which he described series of histopathological changes starting from benign melanocytic nevus passing through dysplastic nevus ultimately leading to melanoma.[13] However, the development of melanoma in the index case appears to be contrary to Clark's model of development of melanoma as there is no history of melanocytic nevus at the site of melanoma, and the nodule was not pigmented. Furthermore, melanoma occurred on the sun-induced damaged area (great toe) and an acral region which are known to have low frequency of BRAF mutations. Moreover, this type of melanoma shows mutations and ⁄ or amplifications of receptor tyrosine kinase KIT,[14] as well as amplifications of cyclin D1 (CCND1) and cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) genes that regulate cell-cycle progression. This indicates that there is a distinct genetic pathway for the development of melanoma depending on the anatomical site of the primary lesion. However, the genomic analysis could not be done in the index case, which could have established mutations and substantiate genetic pathway in the development of melanoma. Furthermore, development of de novo melanoma in the index case is in concert with the hypothesis proposed by Michaloglou et al., which states that the first event in the development of de novo melanoma is unidentified hit which leads to sequence of events consisting of enablement of melanocytes from escape of melanocytes from oncogene-induced senescence, followed by deletion, mutation of the CDKN2A gene, and amplification of CCND1 or CDK4, or Rb mutation.[15]

Malignant melanoma is known for the high rate of metastasis in the skin and subcutaneous tissues, which are of two types; satellite metastasis and in-transit metastasis, both are lymphogenous metastases. We could detect in-transit metastasis in the left inguinal lymph node on FNAC. However, the patient did not consent for lymphnode biopsy, which is a limitation. AMM is prone to metastasize to lymph node earlier than hematogenous metastases.[16] However, there was no evidence of hematogenous metastasis on abdominal ultrasonography, chest X-ray, X-ray skull, and serum LDH levels, were normal. Furthermore, advanced investigations such as whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with diffusion-weighted sequences and fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) could not be done due to financial constraint which could have probably detected metastasis in the index case if present. Moreover, Jouvet et al. while conducting a comparative study between whole-body MRI with diffusion-weighted sequences and FDG-PET/CT involving 37 patients of melanoma Stage IV of AJCC could find whole-body MRI with diffusion-weighted sequences to be reliable with advantage of being nonradiating imaging for staging of melanoma.[17]

Dermatoscopy with the application of four algorithmic methods (qualitative pattern analysis, the ABCD rule of dermatoscopy, the Menzies’ method, and the seven-point checklist) may help in distinguishing benign from malignant melanocytic tumors.[18] However, dermatoscopy could not be done for the index case due to nonavailability.

AMM are also known to involve rectum and anal canal and may present with nonspecific symptoms such as bleeding per rectum, rectal mass, tenesmus, and hemorrhoids.[19] Joshi et al. reported a case of AMM presenting as ulcerated nodule in the rectum which was misdiagnosed as poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of rectum managed by abdominoperineal resection, 3 months later, presented with liver and skeletal metastasis detected on FDG-PET/CT. Finally, the diagnosis was confirmed by the immunohistochemical study of biopsy from deposits in the muscle.[7]

Five types of standard treatment are used for the management of malignant melanoma, which include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, biologic therapy, and targeted therapy. As the index case of AMM is in Stage IIIC, treatment options are: Amputation of left great toe along with lymphnode dissection. However, the patient was lost to follow-up.

AMM has worse prognosis due to delayed diagnosis.[20] However, McClain et al., in their study of 1170 cases of melanomas could find no difference in the prognosis between red melanomas (AMM) and pigmented melanomas.[21] Furthermore, it is also not known whether the prognosis is poorer for patients with AMM metastases than for those with pigmented melanoma metastases.[3]

To conclude, since AMM are devoid of pigment, it is clinically difficult to suspect when presenting atypically such as granuloma pyogenicum. It could be suspected in the index case only because of the presence of multiple pigmented nevi in the vicinity of AMM presenting as granuloma pyogenicum. Hence, the physician should be prudent to suspect malignant melanoma when confronted with a seemingly benign red nodular lesion such as pyogenic granuloma.

Learning points

AMM presenting as granuloma pyogenicum and in the vicinity of acquired melanocytic nevi is rare

As AMM is devoid of pigment, strong suspicion and investigation will help in early diagnosis and treatment

Dermatoscopy with application of four algorithmic methods may help in distinguishing benign from malignant melanocytic tumors

FDG-PET/CT of the whole-body should be done in all cases of malignant melanoma to detect metastasis as it also helps in staging of melanoma

Management of melanoma depends on staging of AJCC TNM system

Treatment of melanoma consists of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, biologic therapy, and targeted therapy.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Development of AMM presenting as granuloma pyogenicum and in the vicinity of acquired melanocytic nevi is unique in the index case.

References

- 1.Miller AJ, Mihm MC., Jr Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:51–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold M, Holterhues C, Hollestein LM, Coebergh JW, Nijsten T, Pukkala E, et al. Trends in incidence and predictions of cutaneous melanoma across Europe up to 2015. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1170–8. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koch SE, Lange JR. Amelanotic melanoma: The great masquerader. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:731–4. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.103981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wain EM, Stefanato CM, Barlow RJ. A clinicopathological surprise: Amelanotic malignant melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:365–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boissy RE, Huizing M, Gahl WA. Biogenesis of melanomas. In: Nordlund JJ, Boissy RE, Hearing VJ, King RA, Oetting WS, Ortenni JP, editors. The Pigmentary System: Physiology and Pathophysiology. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2006. pp. 155–70. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shetty A, Kumar SA, Geethamani V, Rehan M. Amelanotic melanoma masquerading as a superficial small round cell tumor: A diagnostic challenge. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:631. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.143569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joshi PV, Vikram RL, Nusrat JA, Bhat G, Ajinkya SP, Patel AR. Malignant amelanotic melanoma – A diagnostic surprise: Flurodeoxyglocose positron emission tomography-computed tomography and immunohistochemistry clinch the ‘final diagnosis’. J Cancer Ther Res. 2012;8:451–3. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.103533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogawa R, Aoki R, Hyakusoku H. A rare case of intracranial metastatic amelanotic melanoma with cyst. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:548–51. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.7.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ladoyanni E, Abdullah A, Sterne GD, Zaki I. Amelanotic melanoma-“to be or not to be”. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:189–90. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.So NL, Chan CF, Ho KW, Lam YL. Amelanotic melanoma masquerading as a pyogenic granuloma: Caution warranted. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:265.e1–2. doi: 10.12809/hkmj133987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dilek N, Dilek AR, Yunus SY, Sehitoglu I. Amelanotic malignant melanoma: A case study demonstrating pitfall of frequently missed opportunity for early diagnosis. Dermatol Aspects. 2014;2:2. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bristow IR, Bowling J. Amelanotic malignant melanoma tends to occur in sun-exposed skin of elderly individuals dermoscopy as a technique for the early identification of foot melanoma. J Foot Ankle Res. 2009;2:14. doi: 10.1186/1757-1146-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark WH, Jr, Reimer RR, Greene M, Ainsworth AM, Mastrangelo MJ. Origin of familial malignant melanomas from heritable melanocytic lesions.‘The B-K mole syndrome’. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:732–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curtin JA, Busam K, Pinkel D, Bastian BC. Somatic activation of KIT in distinct subtypes of melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4340–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. BRAF (E600) in benign and malignant human tumours. Oncogene. 2008;27:877–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lever WF, Schaumburg Lever G. 8th ed. Philaldelphia: JB Lippincott; 1997. Histopathology of the Skin; pp. 654–79. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jouvet JC, Thomas L, Thomson V, Yanes M, Journe C, Morelec I, et al. Whole-body MRI with diffusion-weighted sequences compared with 18 FDG PET-CT, CT and superficial lymph node ultrasonography in the staging of advanced cutaneous melanoma: A prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:176–85. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steiner A, Pehamberger H, Wolff K. In vivo epiluminescence microscopy of pigmented skin lesions. II. Diagnosis of small pigmented skin lesions and early detection of malignant melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:584–91. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felz MW, Winburn GB, Kallab AM, Lee JR. Anal melanoma: An aggressive malignancy masquerading as hemorrhoids. South Med J. 2001;94:880–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahbari H, Nabai H, Mehregan AH, Mehregan DA, Mehregan DR, Lipinski J. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma: A diagnostic conundrum-presentation of four new cases. Cancer. 1996;77:2052–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960515)77:10<2052::AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClain SE, Mayo KB, Shada AL, Smolkin ME, Patterson JW, Slingluff CL., Jr Amelanotic melanomas presenting as red skin lesions: A diagnostic challenge with potentially lethal consequences. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:420–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]