Abstract

The ultimate goal in dermatological therapy is to use the safest and least number of drugs in order to obtain the best possible effect in the shortest period and at reasonable cost. Rational drug use (RDU) is conventionally defined as the use of an appropriate, efficacious, safe and cost-effective drug given for the right indications in the right dose and formulation, at right time intervals. WHO estimates that more than half of all medicines are prescribed, dispensed or sold inappropriately, and that half of all patients fail to take them correctly as prescribed by the doctor. The process of Rational prescription for a Dermatologist (RPD) involves a series of steps such as defining the patient's illness, specifying the treatment objectives, using the principle of P-treatment, starting the treatment, providing appropriate information and monitoring the treatment. Reasons for irrational prescription could be physician related, patient related, industry related, regulations related. Practicing medicine irrationally can lead to disastrous events like increased morbidity and mortality, drain of resources, drug resistance etc. Principles to enhance the RDU in our practice and minimize errors of prescription are discussed in detail in this article.

Keywords: Essential list of medicines, ideal prescription, irrational prescription, polypharmacy, P-treatment, rational drug therapy

Introduction

What was known?

Irrational drug use is a global phenomenon accounting in more than 50% of prescriptions

Irrational drug use can lead to disastrous impacts such as morbidity and mortality, drain of economic and material resources, and drug resistance

It is in the interest of every stakeholder that we address this problem sincerely.

The Alma-Ata declaration in 1978 reaffirmed that health is a fundamental human right and a social goal.[1] Medicines save lives, promote health and quality of life in a diseased patient.[2]

With the easy accessibility of medications, their misuse has emerged as a major concern. Medically inappropriate, ineffective, and uneconomical uses of drugs occur all over the world. According to the reports of National Rural Health Mission, in India, irrational drug use is a matter of serious concern.[3,4]

The invention of immunomodulators, biologics, botulinum toxin, fillers, etc., has helped to manage satisfactorily conditions such as psoriasis, pemphigus, and few cosmetic conditions.

However, using these high-risk medications irrationally have led to many unwanted ethical, legal, and various other issues. For example, studies have established that patients treated with methotrexate have resulted in increased mortality and a shortened life span than in those who were not treated.[5] Thus, we end up using drugs which have potential to cause serious side effects and adverse reactions for seemingly milder diseases. The ultimate goal in dermatological therapy is to use the safest and the least number of drugs in order to obtain the best possible effect in the shortest period and at reasonable cost.

It is in this context that we, dermatologists, should understand the relevance of rational prescribing. This article describes some of the basic principles governing rational prescription in dermatology that is necessary to achieve the therapeutic goals.

What is Rational use of Drugs?

To quote WHO, rational use of drugs requires that patients receive medications appropriate to their clinical needs, in doses that meet their own individual requirements, for an adequate period of time, and at the lowest cost to them and their community.[4]

Rational drug use is also conventionally defined as the use of an appropriate, efficacious, safe and cost-effective drug given for the right indications in the right dose, and formulation, at right time intervals.[6]

Rational prescribing dermatology is based on the following principles:

Appropriate dermatological indications

The dermatological condition should warrant the use of such medication which is being prescribed.

Appropriate drug

The drug selected for that condition should be based on efficacy, safety, and cost considerations.

Appropriate patient

The patient should satisfy the risk-benefit ratio not having any or minimal contraindications to the use of the drug on him.

Appropriate information

Patients should be provided with relevant information regarding the condition and the medications prescribed.

Appropriate monitoring

List of common side effects, the warning symptoms, and signs to recognize such events explained to the patient, and ways to monitor for the early detection of such adverse events.

The Need for Rational Prescription

With an information explosion available on the internet, huge media publicity regarding the disease and the drugs, and increased consumer awareness, today's patients have become more informative and thus more demanding. Therefore, increasing attention is being paid to inappropriate medication use in these days.

Irrational use of medicines is a major problem worldwide. WHO estimates that more than half of all medicines are prescribed, dispensed, or sold inappropriately and that half of all patients fail to take them correctly as prescribed by the doctor. The institute of medicine report in 2000 provides a detailed report on the situation arising out of inappropriate use of medicines either knowingly or unknowingly.[7]

The Process of Rational Prescribing

To understand this, let us presume that we have to treat a case of psoriasis.

This process consists of six steps, each of which is discussed briefly.[8]

-

Step 1: Define the patient's problem.

This can be made by proper diagnosis and assessing prognosis. Thus in a case of psoriasis, it may involve making a clinical or histopathologic diagnosis and then determine the severity of the disease (mild/moderate/severe).

-

Step 2: Specify the therapeutic objective.

We have to establish the ultimate goal of our therapy (total/near/partial clearance of lesions). We have to explain to the patient that psoriasis is an incurable condition, and the aim of therapy should be to reduce the severity and achieve near control of the disease and not total clearance of the disease in all cases.

-

Step 3: Verify the suitability of your P-drug and P-treatment.

The next step is selecting a modality of therapy (topical/systemic/combination therapy). The choice of selecting a drug depends on a combination of factors such as disease factor, drug factor, patient factor, and physician factors. However, one must identify one's own P-drug. P-drugs and P-treatment are “personal” drugs chosen to prescribe regularly, and with which we have become familiar.[9] They are our priority choice for given indications. This principle is universally valid. P-drugs enable us to avoid repeated searches for a good drug in our daily practice.[10] Furthermore, we will get to know their effects and side effects thoroughly with obvious benefits to the patient.

It is estimated that most doctors use only 40–60[11] drugs routinely. Always choose the P-treatment on the basis of efficacy, safety, suitability, and cost.

Thus, in this case, based on the clinical experience, the author's P-drug would be topical steroids, keratolytics, and/or systemically methotrexate.

-

Step 4: Start the treatment

- Patient communication:

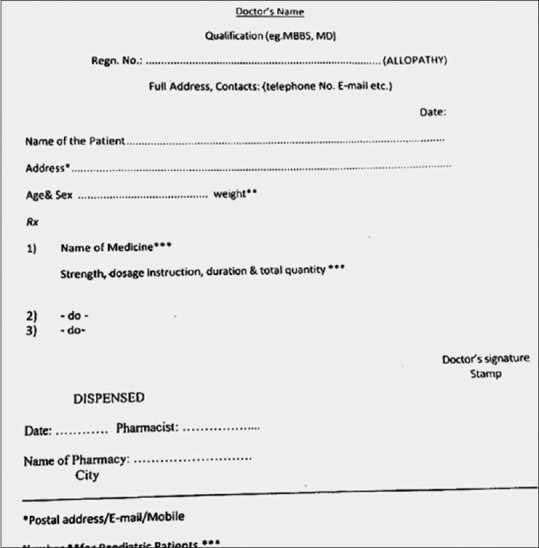

- The advice should be given first, with an explanation of why the drug prescribed is required. Be brief and use words, the patient can understand. Avoid using medical terminologies Writing an ideal prescription: Guidelines for writing an ideal prescription are available which must be referred to. The recent norm for prescription writing given by Medical Council of India (MCI) is shown in the [Figure 1].[12]

Figure 1.

Ideal prescription. Medical Council of India guideline

Information that Must Appear on a Prescription

Name and address of the prescriber, with telephone number (if possible), is extremely essential as it helps for further contact and/or any clarification either by the pharmacist or the patient

Date of the prescription: In some countries, a prescription is only valid for a particular period after the date it was written. This avoids self-medication; no such rigid rules are followed in India. This has resulted in a number of medication errors due to self-medication where the same prescriptions are reused by the patients as and when required

Name, age, and address of the patient. These are important patient identifiers

Name, dosage form, and strength of the drug. It is strongly recommended to use the generic (nonproprietary) name, e.g. methotrexate instead of folitrax. This means that you do not express an opinion about a particular brand of the drug. However, if there is a particular reason to prescribe a special brand, the trade name can be added.

Recently, MCI Code of Medical Ethics: 1.5 issued a re-notification and said that the rule 1.5 should be followed in its spirit. The rule says:

MCI Code of Medical Ethics: 1.5 use of generic names of drugs: “Every physician should, as far as possible, prescribe drugs with generic names and he/she shall ensure that there is a rational prescription and use of drugs.”[12]

The dosage form also needs to be clearly mentioned. For example, tablet, capsule, syrup, injection, etc., The strength of the drug indicates how many milligrams each tablet should contain. Try to avoid decimals and where necessary, write words in full to avoid misunderstanding. Bad handwritten prescriptions can lead to mistakes, and it is the legal duty of the prescriber to write legibly. Instructions for use must be clear, and the maximum daily dose mentioned. Use nonerasable ink. Only use standard abbreviations that will be known to the patient. For example, write by mouth for PO, mg for milligram.

The common prescribing errors can be attributed to the omission of needed information, poor prescription writing, inappropriate drug prescription, and improper communication either verbally or in writing.

Poor communication in the form of illegible medication orders, look-alike drug names, and confusion of brand and generic names, all can and do lead to medication errors.

Step 5: Give information, instructions, and warnings.

The following points should be explained to the patient and also given in a written form.

The need for the medicine

How the medicine helps the patient

How to take the medicine

What benefits to expect

What side effects can occur – common and serious? For example, if the patient is prescribed sedating antihistamines or sedatives etc. A simple warning to avoid driving while on such medications can make a lot of difference[13]

How to monitor for such side effects: Symptoms and signs; laboratory investigations

What type of adverse reactions should be immediately reported?

When to come for follow-up?

At the end, the dermatologist must assess whether the patient/attendant has understood the information when he has finished his consultation.

Step 6: Monitor (and stop) treatment

As many of the systemic drugs used in dermatology can cause various cutaneous and systemic side effects in the short- and long-term phase of drug administration, it is essential to minimize the damage and recognize these side effects early. Hence, periodic monitoring for these side effects should be carried out. The protocols that are laid out for the management of diseases and the use of various drugs should be followed. For example, periodic investigations chart has been recommended for patients on methotrexate therapy.[14] The patient should be advised to follow these instructions carefully during the course of treatment. Deviation from these standard protocols results in irrational prescription.

Reasons for Irrational Prescriptions

Let us try to understand the various reasons why irrational prescribing occurs.

Patient related

Unrealistic expectations demanding immediate cure by the patient may force the prescriber to administer medications irrationally; e.g., methotrexate in limited stages of psoriasis vulgaris. Misinformation about the drugs may sometimes lead to drug abuse such as chronic use of steroids as self-medication in many chronic illnesses.

Physician related

Many dermatologists may not be aware of the published management guidelines. Prescribers must update themselves regularly by reading scientific publications, attending continuing medical educations, and conferences. Such activities would make the prescriber practice evidence-based dermatology rather than generalizing the limited experience.

It is much easier to prescribe a systemic agent than prescribe, educate, and motivate a patient to use topical and or other therapies. Such practices should, however, be avoided. It is reported with reference to topical corticosteroids that peer pressure, rapid feel good effect, and ignorance about harmful effects lead to continuation of treatment beyond prescribed time.[15]

Industry related

Many industries may resort to advertisements with misleading claims and unethical promotional activities. This would adversely affect the prescribing behavior of the dermatologist and also misleads the patients.

Regulatory concerns

Regulatory control on the manufacturing practices, promotional activities by the industry, and dispensing by the pharmacist play a major role in ensuring rational prescriptions. The local regulations of hospitals must ensure that there is evidence-based medical practice. Regular prescription audits and pharmacovigilance program must be conducted in order to sensitize the dermatologists.

Healthcare facilities

The infrastructure of the healthcare facility must be able to manage the huge patient load. In addition, good laboratory facilities will help in proper diagnosis and follow-up of the patient. There should be adequate and regular supply of good quality medicines freely available in the pharmacies all the time.

Common Patterns of Irrational Prescribing

The use of drugs, when no drug therapy is indicated. For example, where seborrheic dermatitis can be controlled with just shampoo rather than with systemic agents

The use of a wrong drug for a specific condition

The use of drugs with doubtful/unproven efficacy. Wrong claims made and off-label indications

The use of drugs of uncertain safety status

Failure to provide available, safe, and effective drugs. Antibiotics versus retinoids in acne management

The use of correct drug with incorrect administration, dosage, and duration. For example, Methotrexate given daily rather than weekly pulse therapy

The use of unnecessary expensive drugs. For example, cyclosporine or biologics versus methotrexate

Errors while monitoring therapy – failing to alter therapy when required, erroneous alteration

-

Prescription errors: This includes:

- Illegibility;

- Using inappropriate abbreviations;

- Look-alike drugs;[16]

- Sound-alike drug names (e.g., ephedrine and epinephrine).

Leading and trailing zeroes: For example, 5 mg of xanax can be mistaken for 5 mg of xanax which can be avoided by writing 0.5 mg.

Another good example is the use of epinephrine. This is a lifesaving drug used in medical emergencies such as anaphylaxis, anaphylactic shock, and myocardial infarction. It can be used in the doses ranging from 0.3 to 1 mg of 1:1000–1:10,000 concentration. It can be administered either intramuscularly or slow intravenous. Improperly instructed, this has a potential to cause life-threatening complications.

Dispensing errors: Dispensing wrong medicines by pharmacist is another important form of medication error

Administration errors: Is mostly done by nurses, is a major cause of medication errors. This can be attributed to workloads, work fatigue, stress, etc

Transcription errors: Failure to follow proper procedure such as double checking the drug, patient identity, etc.

Several studies have clearly shown that physician ordering and nursing administration accounts for nearly 70–80% of medication errors.[17,18]

Thus to summarize, a rational prescription consists of: The right patient being given the right medication and formulation in the right dose at the right time by the right route for the right duration and finally documented rightly.

Impact of Irrational Use of Drugs[19]

Wrong use of medicines can lead to increased morbidity and mortality

Waste of health resources and increased costs

Increased incidence of adverse drug reactions

The emergence of drug resistance, especially with antimicrobials

Risk of transmission of diseases through unsafe injections used while treating patients.

Principles for Rational Prescribing

Explore nonpharmacological approaches the first before starting medications: Every medication is potentially risky. Therefore, explore the nondrug options in the management of the patient wherever possible. Simple measures such as exercise, lifestyle changes, counseling, and diet can help control some dermatological conditions such as acne,[20] psoriasis,[21] and atopic dermatitis. This goes a long way than treating with medications always

Always take a detailed history regarding the health status of the patient. Identify high-risk patients. High-risk patients are those patients who are more susceptible for complications due to drugs. For example: Pregnant and lactating women, children, elderly, patients with renal and/or hepatic failure, history of drug allergy, other co-existing diseases, other concomitant medications, and any alternative modes of treatment the patient may be indulging in

Medication reconciliation is the process of comparing a patient's medication orders to all of the medications that the patient has been taking. This reconciliation is done to avoid medication errors such as omissions, duplications, dosing errors, or drug interactions. It should be done at every transition of care in which new medications are ordered or existing orders are rewritten

Use as minimal drugs as possible. By doing so, one becomes familiar with these drugs. WHO has recommended that average number of drug per prescription should not be more than 2.0.[23] Hence, avoid polypharmacy. Polypharmacy is defined as the concomitant intake of five or more medications by the patient.[24] Using multiple drugs may lead to adverse drug reactions, increase the risk of drug interactions, dispensing errors, decrease adherence to drug regimens, and unnecessary drug expenses. A study done by Thawani et al., showed significant polypharmacy practice among dermatology prescriptions[25]

Use the minimum duration of treatment. Discontinue as many drugs as possible, as early as possible. It is wise to follow standard protocols framed by regulatory authorities for the management of specific diseases. For example, In 2011, the British Association of Dermatologists have framed guidelines on managing certain common dermatological disorders and certain systemic drugs.[26]

Avoid frequent switching over of drugs without clear compelling reasons. Refer to several methods that have been used to measure appropriateness of prescribing, one of which, the medication appropriateness index[27,28] will serve as an example. The most appropriate drugs for patients should be selected according to principles well-described in the WHO “guide to good prescribing”[8]

Have high index of suspicion for adverse drug effects whenever a patient comes with a new symptom. Make sure that they are not related to any of the drugs you have prescribed and if so report to the nearest pharmacovigilance center. Adverse cutaneous drug reactions accounts for about 24% of all adverse drug reactions in one study.[29] Dermatologists have the greatest opportunity in reporting the various reactions that can happen as they come across majority of these drug reactions, prescribed by all sectors of health system such as public and private hospitals, general practitioners, nursing homes, retail dispensaries, and clinics for traditional practice[30]

Educate patients about possible adverse drug reactions in advance so that they can be recognized and reported early

Always keep updated about drugs thoroughly from credible sources (journals, reference books, drug compendia, national lists of essential drugs and treatment guidelines, drug formularies, drug bulletins, drug information centers, pharmaceutical industry sources of information, web references, drug information bulletins, and scientific sessions)

Always evaluate claims for new drugs skeptically. Obtain any high-quality studies published in reputed journals. Guidelines for effective reading and understanding of such articles have been outlined[31] in order to use time efficiently

Do not be seduced by claims made by pharmaceutical companies citing fancy and the latest technology

Be careful to assess compliance to the medication you advised before declaring the drug you have used is not effective

Document the entire prescription details thoroughly. Guidelines have been framed for writing ideal prescriptions

Be careful about critical toxicities. Critical toxicities are defined as any drug-induced adverse effect that may result in either loss of life or potentially irreversible significant morbidity. The following are examples of critical toxicity: Hepatotoxicity, renal toxicity, teratogenicity, agranulocytosis/aplastic anemia, induction of malignancy, opportunistic infections, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal – axis suspension, ocular toxicity, bone toxicity

These adverse effects should receive the highest priority while administering drugs systemically. Close follow-up is required to monitor for such toxicities[32]

Preferably, chose your medicines from the essential list of medicines. They are those medicines which are critically required for the management of 90–95% of common and important conditions in our country. These medicines must all meet with high standards of safety, quality, cost, and efficacy. The 14th model list of Essential Medicines of March 2005 contains 306 medicines in 405 formulations[33]

If required, do not hesitate to take informed consent by making patient aware of the risks, benefits, and alternatives to the proposed therapy.

Way Forward

The current medical curriculum is focused mainly on symptoms and diagnosis. Little or no time is given to the principles of drug treatment. It is advisable to introduce the theory and practical demonstrations on pharmacotherapy. This approach goes a long way to equip medical graduates to assume prescribing responsibilities after graduation and thus prevent avoidable medication errors.

A new era of “personalized” treatment has been predicted in which therapeutic choices will be individualized based on genetic variables affecting drug handling and action, allowing more specific prediction of outcomes. Indeed, pharmacogenetics is already being used to distinguish responders from nonresponders and to avoid adverse effects (e.g. HLA-B 1502 allele and carbamazapine,[34] HLA-B*701 for abacavir hypersensitivity).[35]

Summary

The science of rational prescription should help us to maximize clinical effectiveness and minimize harm to the patient. It involves a series of logical steps in treating the patient; involves a wide range of activities such as adaptation of the P-drug concept, essential drug concept, and continuous professionals’ education program; the development and adaption of evidence-based clinical guidelines; etc. Improved regulatory mechanisms, availability of assured, quality medicines should be an integral part of healthcare services. Practicing the principles of rational prescription for a dermatologist would enable us to go a long way in treating diseases effectively and achieve a high degree of professional satisfaction.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Rational drug therapy involves a series of steps, none of which should be ignored

Various principles such as P-treatment, essential list of medicines, clinical guidelines, and monitoring for critical toxicities should be employed to follow the principles of rational drug therapy

Every stakeholder should play his role meticulously to minimize the disastrous events which can follow irrational drug use

There is a need to modify the current dermatology curriculum to stress the importance of rational drug use.

References

- 1.Declaration of Alma Ata. 1978. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 06]. Available from: http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/declaration_almaata.pdf .

- 2.Kar SS, Pradhan HS, Mohanta GP. Concept of essential medicines and rational use in public health. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:10–3. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.62546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tripathi KD. Essentials of Medical Pharmacology. 6th ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (p) Ltd; 2008. Aspects of pharmacotherapy; clinical pharmacology and drug developement; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Promoting Rational Use of Medicines: Core Components – WHO Policy Perspectives on Medicines. No. 005. 2002. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 23]. http://www.apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Jh3011e/

- 5.Choi HK, Hernán MA, Seeger JD, Robins JM, Wolfe F. Methotrexate and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A prospective study. Lancet. 2002;359:1173–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas M. Rational drug use and the essential drug concept. In: Parthasarthy G, Karin NY, Fort Hansen, Milap C Nahata, editors. Text Book of Clinical Pharmacy Practice. Hyderabad: Orient Longman; 2004. p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors . Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. Institute of Medicine. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Vries TP, Henning RH, Hogerzeil HV, Fresle DA. World Health Organization. Guide to Good Prescribing – A Practical Manual. WHO/DAP/94.11. 1994. [Last accessed on 2015 Mar 18]. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Jwhozip23e/

- 9.Woodcock J. The prospects for “personalized medicine” in drug development and drug therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81:164–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. [Last accessed on 2015 Jun 05]. Available from: http://www.apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/whozip23e/whozip23e.pdf .

- 11. [Last accessed on 2015 Apr 05]. Available from: http://www.karnatakamedicalcouncil.com/upload/tiltviewer/imgs/122D020150212161720297435.PDF .

- 12. [Last accessed on 2015 Mar 27]. Available from: http://www.mciindia.org/RulesandRegulations/Code of Medical Ethics Regulations 2002.aspx .

- 13.Benjamin DM. Driving under the influence of medications: Are physicians and pharmacists adequately informing their patients of the risks of medication use? News and Views [Newsletter of the Toxicology Section of the American Academy of Foreign Sciences] 2002. May, [Last accessed on 2015 Apr 03]. Available from: http://wwwaafsorg/News&Views/Driving Underhtm .

- 14.Roenigk HH, Jr, Auerbach R, Maibach H, Weinstein G, Lebwohl M. Methotrexate in psoriasis: Consensus conference. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:478–85. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70508-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rathi SK, D’souza P. Rational and ethical use of topical corticosteroids based on safety and efficacy. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:251–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.97655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prakash B. Sad confusion of look-alike tablets. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2010;1:50–1. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.73266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, Petersen LA, Small SD, Servi D, et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events. Implications for prevention. ADE Prevention Study Group. JAMA. 1995;274:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leape LL, Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Cooper J, Demonaco HJ, Gallivan T, et al. Systems analysis of adverse drug events.ADE Prevention Study Group. JAMA. 1995;274:35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaturvedi VP, Mathur AG, Anand AC. Rational drug use - As common as common sense? Med J Armed Forces India. 2012;68:206–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Danby FW, Frazier AL, Willett WC, Holmes MD. High school dietary dairy intake and teenage acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:207–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Setty AR, Curhan G, Choi HK. Obesity, waist circumference, weight change, and the risk of psoriasis in women: Nurses’ Health Study II. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1670–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Joint Commission. Medication reconciliation. Sentinel Event Alert. 2006. [Last accessed on 2015 Apr 03]. Available from: http://www.jointcommission.org/SentinelEvents/SentinelEventAlert/sea_35.htm .

- 23.Sharif SI, Al-Shaqra M, Hajjar H, Shamout A, Wess L. Patterns of Drug Prescribing in a Hospital in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. LIJ AOP. 2007;070928:10–12. doi: 10.4176/070928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viktil KK, Blix HS. The impact of clinical pharmacists on drug-related problems and clinical outcomes. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;102:275–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thawani VR, Motghare VM, Dari AD, Shelgaonkar SD. Therapeutic audit of dermatologic prescriptions. Indian J Dermatol. 1995;40:13–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox HN, English SCJ. New Delhi: Wiley Blackwell; 2011. British Association of Dermatologists’ Management Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Samsa GP, Weinberger M, Uttech KM, Lewis IK, et al. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:1045–51. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90144-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samsa GP, Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Weinberger M, Clipp EC, Uttech KM, et al. A summated score for the medication appropriateness index: Development and assessment of clinimetric properties including content validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:891–6. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swamy S, Nadig P, Prakash B, Mohan NT, Shetty M. Profile of suspect adverse drug reactions in a teaching hospital. Int J Recent Trends Sci Technol. 2013;9:86–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prakash B, Singh G. Pharmacovigilance: Scope for a dermatologist. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:490–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.87121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’Costa G, Raj V. National Commission on Excellence in Elementary Teacher Preparation for Teaching Instruction. Prepared to Make a Difference. International Reading Association. The Voluntary Health Association of Goa. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolverton SE, Callen JP. Dermatologic signs of Internal disease. 4th edition. China: Saunders; 2009. Systemic therapy for Cutaneous disease; p. 413. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ch 2. Vadodara, India: Low Cost Standard Therapeutics (LOCOST); 2006. A Lay person's guide to medicines. Vadodara: LOCOST 2006. Essential drugs. A Lay Person's Guide to Medicines What is in Them and What is Behind Them; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hung SI, Chung WH, Jee SH, Chen WC, Chang YT, Lee WR, et al. Genetic susceptibility to carbamazepine-induced cutaneous adverse drug reactions. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2006;16:297–306. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000199500.46842.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rauch A, Nolan D, Martin A, McKinnon E, Almeida C, Mallal S. Prospective genetic screening decreases the incidence of abacavir hypersensitivity reactions in the Western Australian HIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:99–102. doi: 10.1086/504874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]