Abstract

Isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridines are known to be endowed with potent affinity for cyclin G associated kinase (GAK). In this paper, we expanded the structure-activity relationship study by broadening the structural variety at position 3 of the isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridine scaffold. The most potent GAK ligands (displaying Kd values of less than 100 nM) within this series carry an alkoxy group at position 3 of the central scaffold. Unfortunately, these ligands display only modest antiviral activity against the hepatitis C virus.

Introduction

According to reports of the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 170 million people are chronically infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV). Among these patients, 60–70% will suffer chronic liver disease. In 5–20% of cases, liver cirrhosis or liver cancer is diagnosed, resulting in 1–5% lethal outcomes. It is therefore not surprising that HCV infection is a major indication for liver transplantation.1

Historically, treatment of HCV infected patients constituted of parenteral administration of an immunomodulatory agent (pegylated interferon) to stimulate the hosts’ antiviral immune response, in combination with ribavirin. In 2011, the first class of directly acting antiviral agents, the HCV NS3/4A serine protease inhibitors, was added to pegylated interferon and ribavirin with increased efficacy. Currently, three NS3/4A protease inhibitors have been licensed for clinical use (Boceprevir,2 Telaprevir,3 Simeprevir4). Another class of HCV therapeutics constitutes the NS5A inhibitors, from which Daclatasvir received marketing approval.5 Very recently, sofosbuvir, a uridine nucleotide analogue acting as a HCV NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor was approved by the FDA.6 It has emerged as a potent agent with pan-genotypic efficacy (HCV genotypes 1-6), a high barrier to resistance and it established the backbone of an interferon- and ribavirin-free regimens. These existing treatments target viral factors which are essential for replication of HCV, and more specifically, the step of HCV RNA replication. An alternative strategy, which is much less explored, is the development of compounds that target cellular host factors.7 This approach has the potential advantage of offering a higher genetic barrier to resistance, since viral mutations are less able to compensate for the loss of essential host factors. In addition, different viruses can depend on the same cellular factor for their replication. Hence, targeting such a common host factor with small molecules may lead to the discovery of broad-spectrum antivirals. A potential limitation is drug-induced toxicity, since some of these factors may be essential for normal cellular functioning. Multiple cellular factors are involved in the HCV life cycle and therefore represent potential targets for antiviral treatment.8 The best studied and validated cellular targets for anti-HCV treatment are the cyclophylins A, a family of enzymes with peptidyl-prolyl isomerase activity. DEB025 (alisporivir) is among the most clinically advanced representatives of the cyclophilin A inhibitors and has advanced to phase III clinical trials.9 Besides cyclophilins, a number of other cellular proteins have been identified as HCV cofactors by siRNA screening campaigns.10-14 A common target identified in various screens are the phosphatidylinositol-4-kinases IIIα and β. Small molecule inhibitors of these enzymes have been synthesized and found to be endowed with potent activity against HCV.15-16 Alpha-glucosidase I is another example of a host factor essential for HCV infection. Alpha-glucosidase I inhibitors, such as celgosivir, have been shown to inhibit replication of HCV as well as Dengue virus.17-18

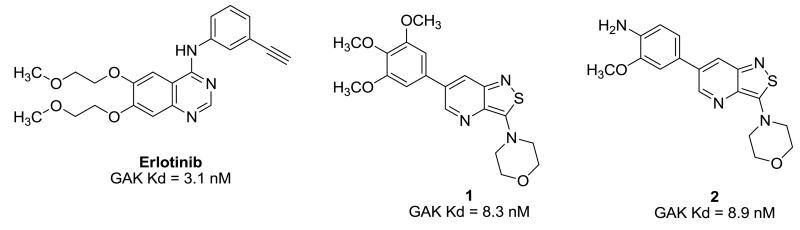

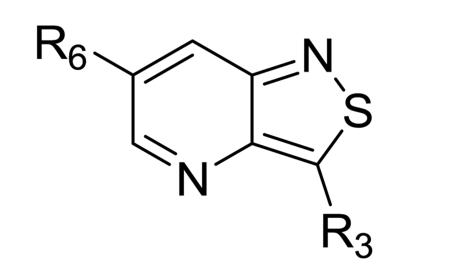

Recently, cyclin G associated kinase (GAK) emerged as a promising target for the treatment of HCV infections. GAK is a host cell kinase known to regulate interactions between clathrin adaptor complexes and host cargo proteins. It has been shown that depletion of GAK by siRNA is dispensable for HCV RNA replication, but significantly inhibits two temporally distinct steps of the HCV life cycle: entry and assembly.19,20 Similarly, pharmacological inhibitors of the kinase activity of GAK disrupted HCV entry and assembly, thereby further validating GAK as a potential antiviral target. Erlotinib (Figure 1), an approved anticancer drug that potently inhibits GAK as an off-target effect, effectively disrupted HCV entry and assembly.19,20 Moreover, we recently reported the discovery of isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridines as a class of selective GAK inhibitors that are structurally unrelated to erlotinib.21 The most potent compounds, 1 and 2, were endowed with Kd values of 8.3 and 8.9 nM, respectively (Figure 1). Both analogues were endowed with potent in vitro anti-HCV activity by inhibiting HCV entry and assembly. In this paper, we embark on the synthesis and structure-activity relationship (SAR) study of novel isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridines, with a focus on the expansion of the structural variety at position 3 of the core scaffold.

Figure 1.

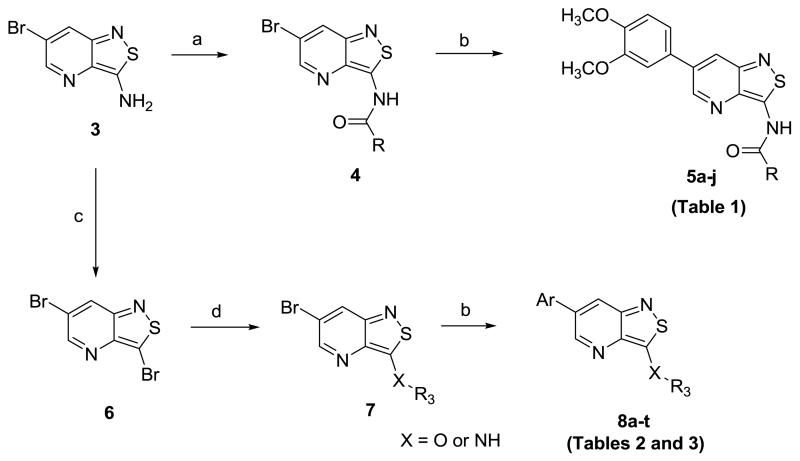

Chemistry

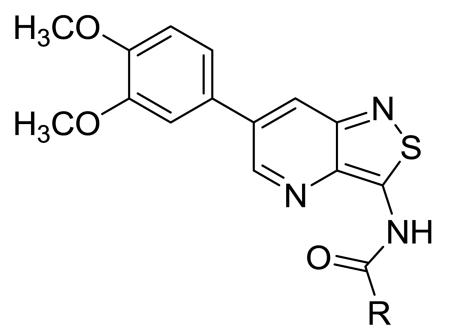

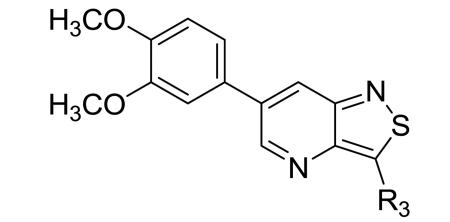

The synthesis started with the large-scale synthesis of 3-amino-6-bromo-isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridine 3 as a key building block, according to a known procedure (Scheme 1).19 The exocyclic amino group was used to prepare a series of amides. As coupling with acid chlorides led inevitably to the formation of di-acylated compound, the amides 4 were prepared by mixing 3 with an appropriate carboxylic acid using O-(benzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium tetrafluoroborate (TBTU) or 1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium-3-oxide hexafluorophosphate (HATU) as coupling reagent. Introduction of the 3,4-dimethoxyphenyl moiety via a Suzuki type of reaction, furnished a small library of N-(6-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridin-3-yl)amide derivatives 5a-j. Diazotation of the exocyclic amino group of 3 using sodium nitrite, hydrogen bromide and copper(I) bromide afforded 3,6-dibromo-isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridine 6. The bromine at position 3 was selectively displaced by a number of nitrogen and oxygen nucleophiles. For oxygen nucleophiles, the reactions took place under microwave irradiation, whereas amines were introduced under classical heating conditions. Subsequently, a palladium-catalyzed Suzuki cross-coupling reaction with 3,4-dimethoxyphenylboronic acid or 3-thienylboronic acid afforded a series of 3-substituted-6-aryl-isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridine analogues 8a-t.

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions a) RCOOH, TBTU or HATU, DIPEA, DMF, rt; b) arylboronic acid, K2CO3, Pd(PPh3)4, reflux, H2O, dioxane or DME; c) 30% aq. H2O2, CH3OH, rt; d) R3OH, NaH, μW or R3NH2, EtOH, 75°C.

GAK affinity data and Structure-Activity Relationship studies

The compounds were assayed for their binding affinity for GAK, using the KINOMEscan Profiling Service of DiscoveRx.22 This is based on a competition binding assay that quantitatively measures the ability of a compound to compete with an immobilized, active-site-directed ligand. The binding of DNA-tagged GAK to an immobilized ligand on the solid support is measured by quantitative PCR of the DNA tag. The experiment is then repeated in the presence of a “free test” compound. The more test compounds that bind to GAK, the fewer DNA-tagged GAK enzyme will bind to the immobilized ligand. In a first round of screening, compounds were tested at a single concentration of 10 μM. The results are expressed as % of control (%Ctrl), with high affinity compounds have %Ctrl = 0, while weaker binders have higher % control values. For compounds that display a % Ctrl of less than 5, exact dissociation constant (Kd) values were calculated, using dose-response curves.

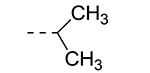

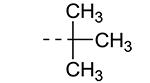

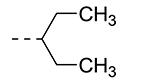

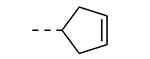

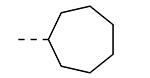

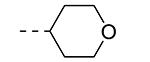

An earlier report focused on morpholino-like substituents at position 3 of the isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridine scaffold.21 Initial data from this paper indicate that structural variation is tolerated at this position. Therefore, further SAR studies in this region might yield important information for GAK inhibition by isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridines. This prompted us to embark on the synthesis of three different series of isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridines, carrying alkoxy, amine and amide substituents at position 3. Table 1 summarizes the GAK affinity data of isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridines, bearing an amide group at position 3. Different aliphatic moieties (such as a methyl, ethyl, isopropyl, tert-butyl and 2-ethyl-propyl) were introduced, albeit all of them lacked GAK affinity. A small cyclo-aliphatic substituent, such as a cyclopropyl (compound 5f), yielded an isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridine derivative with potent GAK affinity (Kd value of 1.1 μM). The introduction of bulkier cyclo-aliphatics, such as a cyclopentenyl (compound 5g), a cycloheptyl (compound 5h), or a tetrahydropyranyl (compound 5i) reduced the affinity to GAK. In contrast, the presence of an aromatic phenyl ring afforded compound 5j, which is endowed with potent GAK affinity (Kd = 0.6 μM).

Table 1.

| Cmpd# | R | % Ctrl (10 μM)a | Kd (μM)a |

|---|---|---|---|

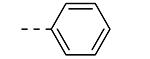

| 5a |

|

54 | ND |

| 5b |

|

15 | ND |

| 5c |

|

29 | ND |

| 5d |

|

66 | ND |

| 5e |

|

90 | ND |

| 5f |

|

2.3 | 1.1 |

| 5g |

|

15 | ND |

| 5h |

|

88 | ND |

| 5i |

|

58 | ND |

| 5j |

|

2.2 | 0.6 |

ND = not determined.

Values are the average of two independent experiments.

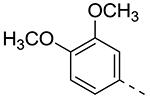

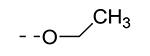

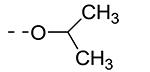

Previously, alkoxy groups were not explored as potential substituents at position 3 of the scaffold, mainly because in the original matrix, the 3-methoxy analogue 8a was devoid of GAK affinity.21 Surprisingly, enlarging the group from a methoxy to an isopropoxy (compound 8b) led to a drastic increase in GAK affinity, with a Kd value of 0.085 μM. The presence of a racemic 2-methoxybutyl group (compound 8c) furnished a compound which was slightly more potent as GAK ligand (Kd = 0.074 μM). Elongation of the chain length to an n-butoxy (compound 8d) reduced GAK binding (Kd = 0.31 μM), whereas the addition of one single carbon (an n-pentyloxy group as in compound 8e) completely abolished GAK affinity. These findings demonstrate the importance of the chain length of the alkoxy group in GAK binding. Branching of the n-butoxy group of compound 8d, yielded the isoamyloxy derivative 8f which displays a Kd value of 0.59 μM, and hence is equally active as its linear counterpart. A cyclic derivative, as exemplified by the synthesis of the 3-cyclohexyloxy derivative 8g, is a potent GAK ligand, endowed with a Kd value of 0.34 μM.

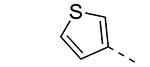

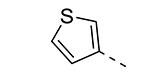

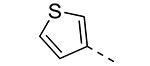

We have shown before that a 3,4-dimethoxyphenyl group can be replaced by a 3-thienyl moiety with retention of GAK affinity.21 Therefore, a number of 6-(3-thienyl)-3-alkoxy-isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridines were evaluated for their GAK binding properties. Similar to the 3,4-dimethoxyphenyl series, the 3-methoxy-analogue 8h is devoid of GAK affinity, whereas the 3-ethoxy- (compound 8i) and 3-isopropoxy- (compound 8j) derivatives are potent GAK ligands, with Kd values of 0.22 μM, and 0.11 μM, respectively. It seems however that the beneficial effect of the isopropoxy group is less pronounced in the 3-thienyl series than in the 3,4-dimethoxyphenyl series.

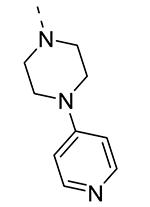

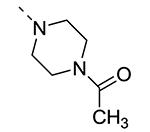

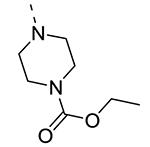

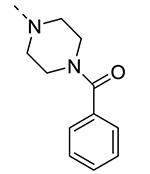

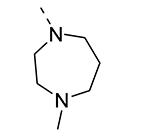

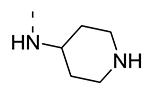

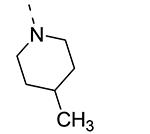

Piperazine substructures are often used in medicinal chemistry optimization campaigns. They are cheap chemicals and are privileged substructures. In addition, the second nitrogen functions as a chemical handle, where a wealth of structural variety can be introduced. As previously shown, an N-Me-piperazinyl group at position 3 (compound 8k) is devoid of GAK affinity (Table 3).21 Increasing the size to an N-isopropyl-piperazino (compound 8l), a n-butyl-piperazino (compound 8m) or a 4-pyridyl-piperazino substituent (compound 8n) did not lead to any improvement in GAK affinity. Besides these N-alkyl/N-aryl piperazines, the second nitrogen of the piperazine group was also coupled to a number of acid chlorides, affording a series of amides. The N-acetyl derivative (compound 8o) and a small carbamate derivative (compound 8p) both show pronounced GAK affinity (Kd values of 0.29 μM and 0.61 μM, respectively), when compared to the parent N-Me-piperazinyl analogue 8k. In contrast, increasing the size of the N-acyl group (yielding benzoyl derivative 8q) led to an inactive compound. In addition, a number of piperazine isosters was prepared, including a N-homopiperazine derivative (compound 8r), an N-aminopiperidine analogue (compound 8s) and a N-piperidino congener (compound 8t). They are endowed with GAK Kd values in the range of 0.61 – 0.9 μM, indicating that these heterocycles are suitable for further medicinal chemistry work in order to improve GAK affinity.

Table 3.

| Cmpd# | R3 | % Ctrl (10 μM)a | Kd (μM)a |

|---|---|---|---|

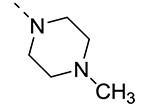

| 8k |

|

19b | ND |

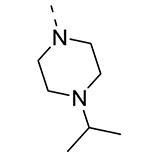

| 8l |

|

11 | ND |

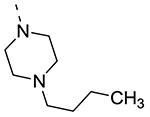

| 8m |

|

52 | ND |

| 8n |

|

23 | ND |

| 8o |

|

0.7 | 0.29 |

| 8p |

|

5 | 0.61 |

| 8q |

|

12 | ND |

| 8r |

|

0.4 | 0.9 |

| 8s |

|

0.25 | 0.64 |

| 8t |

|

2 | 0.66 |

ND = not determined.

Values are the average of two independent experiments.

Literature value

Antiviral activity

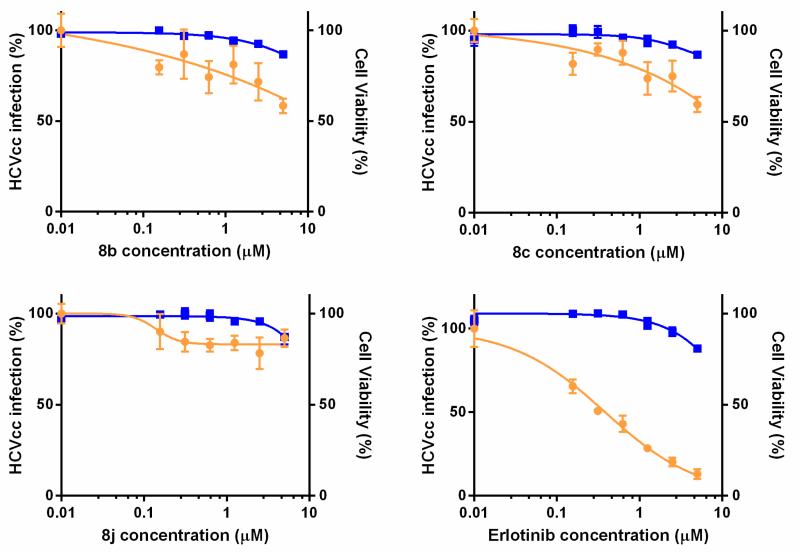

It has been shown before that GAK is involved in the regulation of HCV entry and assembly.19,20 Small-molecule GAK inhibitors, such as the known anticancer agent erlotinib (developed as an EGFR inhibitor, but displays a potent GAK affinity as an off-target effect)19,20 and isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridines (developed as selective GAK inhibitors) have potent anti-HCV activity.19 Therefore, the three most potent GAK ligands (8b, 8c and 8j) from the current SAR study were tested for their antiviral activity. Erlotinib, a very potent GAK ligand (Kd = 3.1 nM), was included as a positive control (Figure 2). The antiviral activity of these compounds was tested in Huh-7.5 cells infected with J6/JFH(p7-Rluc2A) HCV, a recombinant culture grown virus harboring a Renilla luciferase gene.23 Cells were pretreated with various concentrations of 8b, 8c, 8j, or erlotinib for 30 minutes prior to infection. Growth media was replaced daily with compounds containing media. Antiviral activity and cell viability were assessed by luciferase assays and AlamarBlue-based assays 72 hours postinfection, respectively.

Figure 2.

Selective GAK inhibitors inhibit HCV infection. Dose response curves of 8b, 8c, 8j, and erlotinib effects on infection of Huh-7.5 cells with cell culture grown HCV (HCVcc). Plotted in orange (left y-axes) are percentage of luminescence values compared to DMSO treated controls. Corresponding cellular viability, as measured by alamarBlue-based assays, are plotted in blue (right y-axes). Data reflect means and s.d. (error bars).

As shown in Figure 2, the least potent GAK ligand (compound 8j, Kd = 0.11 μM) had a minimal to no effect on the HCV replication. The two more potent GAK ligands (compound 8b; Kd = 0.085 μM and compound 8c; Kd = 0.074 μM), do display a dose-response curve, although they are clearly less potent than the positive control, erlotinib. The effect of these compounds on HCV replication thus appears to correlate with their affinity to GAK. The EC50 for 8b and 8c are >5 μM and >14 μM, respectively. This diminished cellular activity is possibly due to the poor cellular permeability of the compounds or the metabolic instability of the compounds in hepatocytes.

Conclusion

Recently, we have reported the discovery of a novel series of isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridines that act as potent and selective GAK inhibitors.21 In this manuscript, we describe an extension of the SAR of this first series of compounds and demonstrate that a wide variety of substituents can be introduced at position 3 of the isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridine scaffold, besides the parent morpholine group. These data suggest that structural variety at this position is quite tolerated and allows retaining an acceptable GAK affinity. The most potent GAK ligands within this series are the 3-alkoxy-isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridines. The ligands display only modest anti-HCV activity in correlation with their affinity to GAK. These results suggest that compounds with very high affinity for GAK (with Kd values in the low nanomolar range) are necessary to achieve potent antiviral activity.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

| Cmpd# | R6 | R3 | % Ctrl (10 μM)a | Kd (μM)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

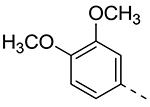

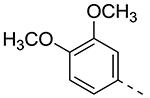

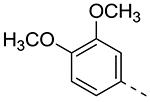

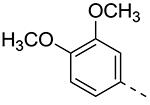

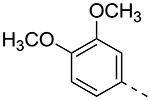

| 8a |

|

|

19b | ND |

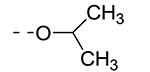

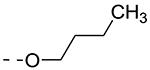

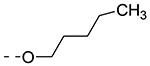

| 8b |

|

|

0 | 0.085 |

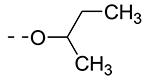

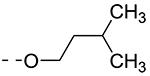

| 8c |

|

|

0 | 0.074 |

| 8d |

|

|

0.8 | 0.31 |

| 8e |

|

|

27 | ND |

| 8f |

|

|

4.7 | 0.59 |

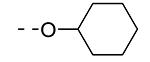

| 8g |

|

|

0.95 | 0.34 |

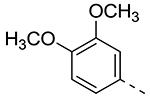

| 8h |

|

|

22b | ND |

| 8i |

|

|

0.55 | 0.22 |

| 8j |

|

|

0.11 | 0.11 |

ND = not determined.

Values are the average of two independent experiments.

Literature value.

References

- (1).Homie Razavi H, ElKhoury AC, Elbasha E, Estes C, Pasini K, Poynard T, Kumar R. Hepatology. 2013;57:2164–2170. doi: 10.1002/hep.26218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Venkatraman S. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2012;33:289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Kwong AD, Kauffman RS, Hurter P, Mueller P. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:993–1003. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Rosenquist A, Samuelsson B, Johansson PO, Cummings MD, Lenz O, Raboisson P, Simmen K, Vendeville S, de Kock H, Nilsson M, Horvath A, Kalmeijer R, de la Rosa G, Beaumont-Mauviel M. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:1802–1811. doi: 10.1021/jm401507s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Liang TJ, Ghany MG. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:1907–1917. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1213651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Kattakuzhy S, Levy R, Kottilil S. Hepatol. Int. 2015;9:161–173. doi: 10.1007/s12072-014-9606-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Bekerman E, Einav S. Science. 2015;348:282–283. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa3778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).von Hahn T, Ciesek S, Manns MP. Discov Med. 2011;12:237–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Naoumov NV. J. Hepatol. 2014;61:1166–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Tai AW, Benita Y, Peng LF, Kim S, Sakamoto N, Xavier RJ, Chung RT. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Randall G, Panis M, Cooper JD, Tellinghuisen TL, Sukhodolets KE, Pfeffer S, Landthaler M, Landgraf P, Kan S, Lindenbach BD, Chien M, Weir DB, Russo JJ, Ju J, Brownstein MJ, Sheridan R, Sander C, Zavolan M, Tusch T, Rice CM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007;104:12884–12889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704894104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Ng TI, Mo H, Pilot-Matias T, He Y, Koev G, Krishnan P, Mondal R, Pithawalla R, He W, Dekhtyar T, Packer J, Schurdak M, Molla A. Hepatology. 2007;45:1413–1421. doi: 10.1002/hep.21608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Supekova L, Supek F, Lee J, Chen S, Gray N, Pezacki JP, Schlapbach A, Schultz P. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:29–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Trotard M, Lepère-Douard C, Régeard M, Piquet-Pellorce C, Lavilette D, Cosset F, Gripon P, Le Seyec J. FASEB J. 2009;23:3780–3789. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-131920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Leivers AL, Tallant M, Shotwell JB, Dickerson S, Leivers MR, McDonald OB, Gobel J, Creech KL, Strum SL, Mathis A, Rogers S, Moore CB, Botyanszki J. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:2091–2106. doi: 10.1021/jm400781h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Mejdrova I, Chalupska D, Kögler M, Sala M, Plackova P, Baumlova A, Hrebabecky H, Prochazkova E, Dejmek M, Guillon R, Strunin D, Weber J, Lee G, Birkus G, Mertlikova-Kaiserova H, Boura E, Nencka R. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:3767–3793. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Durantel D. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2009;10:860–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Rathore AP, Paradkar PN, Watanabe S, Tan KH, Sung C, Connolly JE, Low J, Ooi EE, Vasudevan SG. Antiviral Res. 2011;92:453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Neveu G, Barouch-Bentov R, Ziv-Av A, Gerber D, Jacob Y, Einav S. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002845. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Neveu G, Ziv-Av A, Barouch-Bentov R, Berkerman E, Mulholland J;, Einav S. J. Virol. 2015;89:4387–4404. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02705-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Kovackova S, Chang L, Bekerman E, Neveu G, Barouch-Bentov R, Chaikuad A, Heroven C, Šála M, De Jonghe S, Knapp S, Einav S, Herdewijn P. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:3393–3410. doi: 10.1021/jm501759m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Fabian MA, Biggs WH, Treiber DK, Atteridge CE, Azimioara MD, Benedetti MG, Carter TA, Ciceri P, Edeen PT, Floyd M, Ford JM, Galvin M, Gerlach JL, Grotzfeld RM, Herrgard S, Insko DE, Insko MA, Lai AG, Lélias J, Mehta SA, Milanov ZV, Velasco AM, Wodicka LM, Patel HP, Zarrinkar PP, Lockhart DJ. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:329–336. doi: 10.1038/nbt1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Murray CL, Jones CT, Tassello J, Rice CM. J. Virol. 2007;81:10220–10231. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00793-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.