Significance

Damage to axons in the CNS typically results in permanent functional deficits. Boosting intrinsic programs such as mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling can dramatically augment the axon regenerative capacity of injured neurons. Because certain types of neurons respond to axotomy by maintaining their mTOR activation, we hypothesized that it might be helpful to use this property to promote axon regeneration. We found that the light-responsive G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) melanopsin could promote axonal regeneration after optic nerve crush by activating mTOR. We also showed that light, Gq/11 signaling, and neuronal activity contribute to the mechanism that underlies this effect. Activating Gq signaling through a chemogenetic approach promoted axon regeneration. Thus, we provided evidence for modulating neuronal activity through GPCR signaling in regulating intrinsic axon growth capacity.

Keywords: axon regeneration, neuronal activity, melanopsin, GPCR, mTOR

Abstract

Cell-type–specific G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling regulates distinct neuronal responses to various stimuli and is essential for axon guidance and targeting during development. However, its function in axonal regeneration in the mature CNS remains elusive. We found that subtypes of intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) in mice maintained high mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) levels after axotomy and that the light-sensitive GPCR melanopsin mediated this sustained expression. Melanopsin overexpression in the RGCs stimulated axonal regeneration after optic nerve crush by up-regulating mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1). The extent of the regeneration was comparable to that observed after phosphatase and tensin homolog (Pten) knockdown. Both the axon regeneration and mTOR activity that were enhanced by melanopsin required light stimulation and Gq/11 signaling. Specifically, activating Gq in RGCs elevated mTOR activation and promoted axonal regeneration. Melanopsin overexpression in RGCs enhanced the amplitude and duration of their light response, and silencing them with Kir2.1 significantly suppressed the increased mTOR signaling and axon regeneration that were induced by melanopsin. Thus, our results provide a strategy to promote axon regeneration after CNS injury by modulating neuronal activity through GPCR signaling.

Severed axons in the adult mammalian CNS do not spontaneously regenerate to restore lost functions. The failure of axons to regenerate is mainly attributed to the diminished growth capacity of neurons as well as an inhibitory environment (1–6). Optic nerves have been extensively studied for mechanisms regulating axon regeneration in CNS. When presented with permissive substrates such as a sciatic nerve graft, only axons of small populations of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) regrow into the graft (7). When the intrinsic growth program is boosted, distinct subtypes of RGCs regenerate their axons (8). These findings indicate that the differential responses of RGCs to axotomy and growth stimulation are related to their intrinsic properties. One of the critical determinants of the intrinsic regenerative abilities of adult RGCs is neuronal mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activity (9). In retinal axons, the loss of the potential to regrow is accompanied by down-regulation of mTOR activity in RGCs with maturation, and further reduction after axotomy. However, a small percentage of RGCs maintain high mTOR activation levels after optic nerve crush (9, 10). One can ask whether specific subsets of RGCs differ in their ability to maintain mTOR activation. Deciphering the physiological mechanism behind the mTOR maintenance could help elucidate the differential responses of neurons to injury signals and develop strategies to promote axon regeneration.

Type 1 melanopsin expressing intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (M1 ipRGCs) and αRGCs are resistant to axotomy-induced cell death (8, 11). M1 ipRGCs mainly mediate the circadian photoentrainment and the pupillary light reflex function, with their dendrites stratifying in the outermost sublamina of the inner plexiform layer. αRGCs have largest somata among RGCs, and their dendrites are rich in a neurofilament-associated epitope SMI32. Interestingly, axotomy causes dendritic arbor retraction in αRGCs, but not in M1 ipRGCs (10, 11), suggesting subtype-specific responses to lesions. We hypothesized that mTOR signaling could be differentially regulated in these types of RGCs. Here, we show that M1–M3 ipRGCs but not αRGCs maintain mTOR on injury and that this effect is diminished in melanopsin knockout (KO) mice. Ectopic melanopsin overexpression in RGCs promoted axonal regeneration by activating mTORC1. Furthermore, we provide evidence that mTOR up-regulation and axon regeneration depend on light stimulation and Gq/11 signaling and, subsequently, enhanced neuronal activity. Together, our work identifies a mechanistic link between axon regeneration and neuronal activity in vivo and provides an intrinsic factor that can be exploited to promote neural repair after injury.

Results

Melanopsin Regulates mTOR Activity in RGCs.

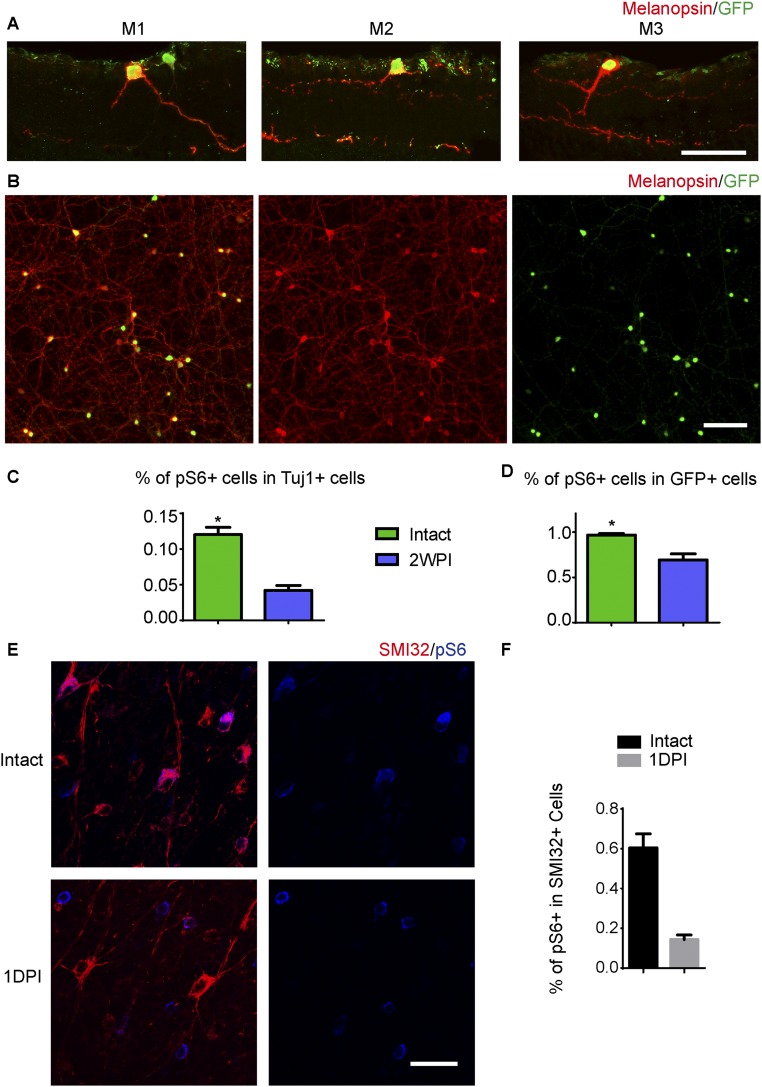

We started the investigation using mice in which GFP expression is driven by the melanopsin promoter (Opn4-GFP) to mark ipRGCs (12), whereas SMI32 staining was used to mark αRGCs and Tuj1 staining was used as a general RGC marker. In the Opn4-GFP mouse line, GFP mainly labels M1–M3 ipRGCs (Fig. S1A), which express higher levels of melanopsin than other types of ipRGCs. More than 95% of the GFP+ cells could be labeled with a melanopsin antibody (Fig. S1B). We examined the levels of phosphorylated S6 ribosomal protein (pS6) signal, an indicator of mTOR, in adult RGCs with or without axotomy. In intact mice, ∼95% of the GFP+ ipRGCs expressed high levels of pS6 (Fig. 1A). One day after injury, the percentage of pS6+ RGCs was decreased to half (Fig. 1B). However, the GFP+ ipRGCs maintained a similar level of pS6 signal (Fig. 1C). Even at 2 wk after injury, when the M1 ipRGCs were the predominant surviving ipRGCs (8), pS6 was still highly expressed in more than 70% of the GFP+ cells (Fig. S1 C and D). With respect to the αRGCs, pS6 was highly expressed in ∼60% of the intact SMI32+ cells with large somata. After axotomy, pS6 expression in the αRGCs was significantly suppressed (Fig. S1 E and F). Our results indicate that M1–M3 ipRGCs maintained mTOR activation after axotomy.

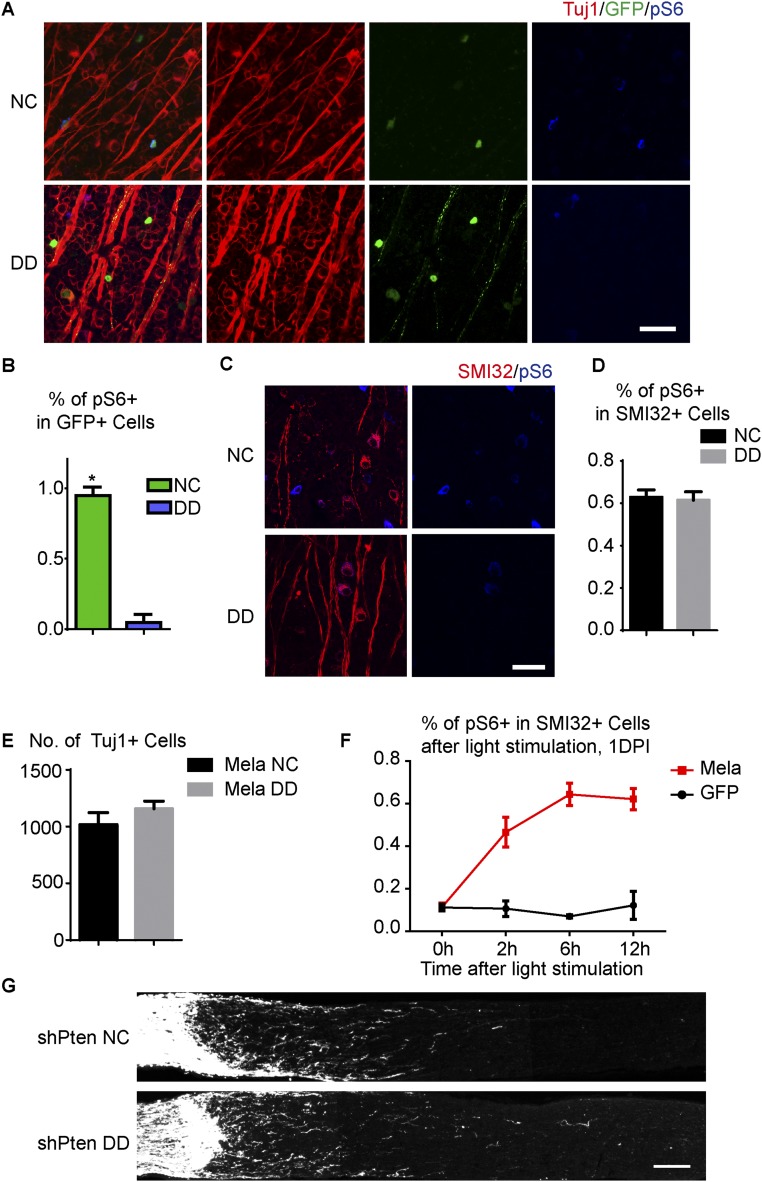

Fig. S1.

Differential mTOR activation in M1–M3 ipRGCs and αRGCs upon axotomy. (A) GFP-labeled M1–M3 ipRGC subtypes in the retina of an Opn4-GFP mouse. Colocalization between GFP (green) and melanopsin (red) staining is shown to illustrate dendritic stratification in the inner plexiform layer, between the inner nuclear layer and the ganglion cell layer. (B) Image of a whole-mounted retina showing double labeling for GFP (green) and melanopsin (red) in Opn4-GFP mice. More than 90% of the GFP+ cells were costained with the melanopsin antibody. (C) Quantification of the percentages of Tuj1+ RGCs that express pS6 in intact and 2WPI retinas of Opn4-GFP mice. (D) Quantification of the percentage of GFP+ ipRGCs that express pS6 in intact and 2WPI retinas. *P < 0.05, Student’s t test, three mice in each group. (E) Whole-mount retinas from WT mice with intact optic nerves or at 1 d postinjury (1DPI). Retinas were stained with SMI32 (red) and pS6 (blue) antibodies. SMI32 labels αRGCs. (F) Quantification of the percentages of SMI32+ αRGCs that express pS6 in intact and 1DPI retinas. *P < 0.05, Student’s t test, three mice in each group. (Scale bars: A, 50 μm; B, 100 μm; E, 15 μm.)

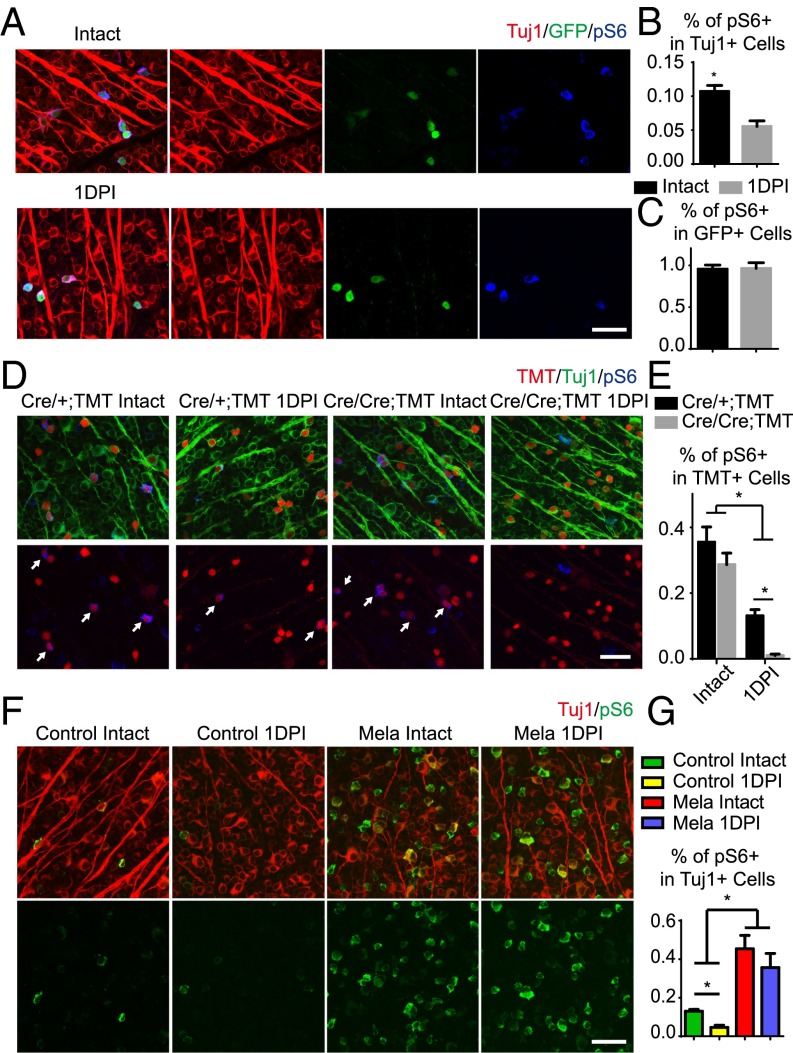

Fig. 1.

Melanopsin regulates mTOR activity in RGCs. (A) Whole-mount retinas from Opn4-GFP mice with intact optic nerves or at 1 d post injury (1DPI), with Tuj1 (red), pS6 (blue), and GFP (green) staining. (B and C) Quantification of the percentages of Tuj1+ RGCs (B) or GFP+ ipRGCs (C) expressing pS6. *P < 0.05, Student’s t test, three mice in each group. (D) Whole-mount retinas from Opn4−Cre/+;TMT and Opn4-Cre/Cre;TMT mice with intact or 1DPI optic nerves, with Tuj1 (red) and pS6 (blue) staining. Arrows point to TMT+ cells expressing pS6. (E) Quantification of the percentages of TMT+ ipRGCs expressing pS6. *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, three to five mice in each group. (F) Whole-mount retinas from WT mice injected with AAV-GFP or AAV-Mela with intact or 1DPI optic nerves, with Tuj1 (red) and pS6 (green) staining. (G) Quantification of the percentage of Tuj1+ RGCs expressing pS6. *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, three to five mice in each group. (Scale bars, A, D, F, 50 μm.)

M1–M3 ipRGCs express high levels of melanopsin. We next asked whether melanopsin played a role in mTOR expression in M1–M3 ipRGCs after axotomy. We crossed knock-in mice (Opn4-Cre) that express Cre recombinase in place of melanopsin within the ORF (13) to a Cre-dependent tdTomato reporter line (Rosa26-TMT). M1–M3 and other ipRGCs are genetically labeled in Opn4Cre/+;TMT mice, whereas in Opn4Cre/Cre;TMT mice, melanopsin is deleted from ipRGCs. TMT+ ipRGCs represented all types of ipRGCs, and GFP+ ipRGCs represented M1–M3 ipRGCs. The pS6 signal was in more than 30% of TMT+ ipRGCs in uninjured animals (Fig. 1 D and E). The pS6 level did not significantly differ between the Opn4 heterozygous and Opn4 KO mice (Fig. 1 D and E). One day after injury, in contrast to GFP+ ipRGCs, the pS6+ cells in TMT+ ipRGCs decreased more than half in the Opn4 heterozygous mice (Fig. 1 D and E). It has been reported that On αRGCs are M4 ipRGCs, in which a lower level of melanopsin is expressed. Because axotomy suppressed pS6 in αRGCs (Fig. S1 E and F), it is likely M4 ipRGCs contributed to ipRGCs that down-regulated pS6. Consistent with the pS6 maintenance in GFP+ ipRGCs, some TMT+ ipRGCs still expressed a high level of pS6 after injury. In Opn4 KO mice, pS6 was dramatically suppressed in the vast majority of TMT+ ipRGCs, presumably including M1–M3 types, leaving few TMT+ cells that expressed pS6 (Fig. 1 D and E). Thus, our results suggest that melanopsin is required for the maintenance of mTOR in M1–M3 cells after axotomy.

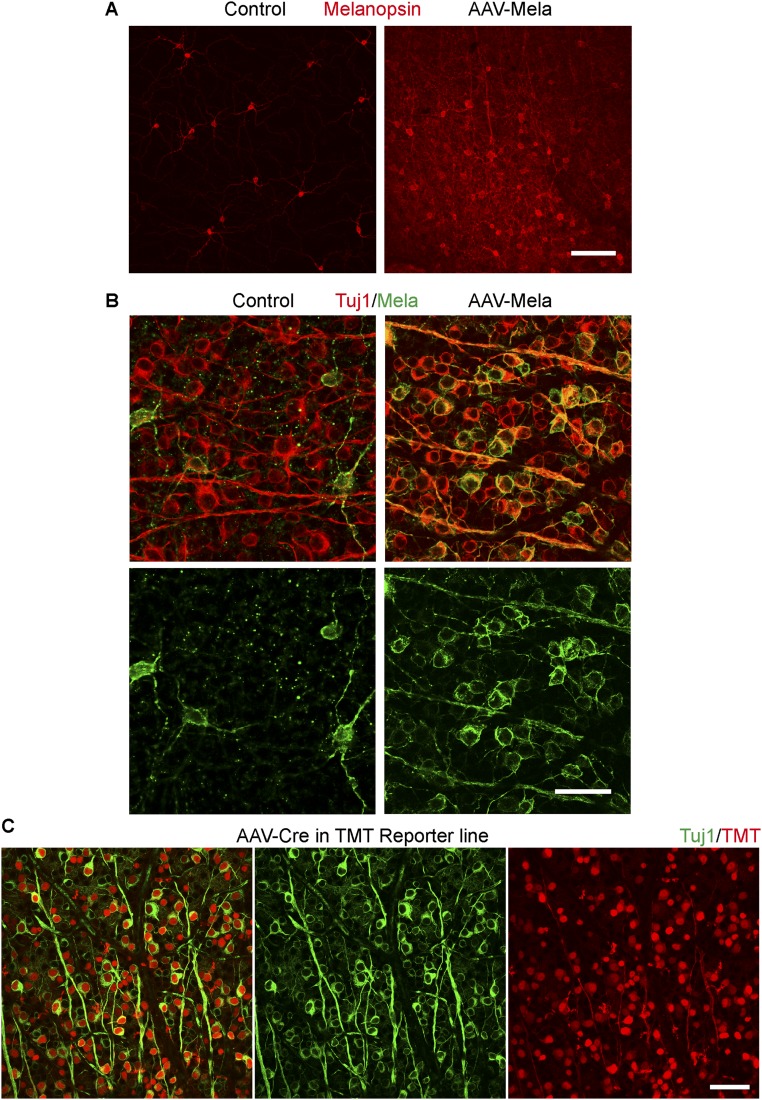

Then we assessed whether melanopsin regulates mTOR activation in RGCs by a gain-of-function experiment. We injected adeno-associated virus (AAV)-expressing melanopsin (AAV-Mela) into the eyes of mice to infect RGCs in retinas (14). Within the whole retina, ∼30% of RGCs were strongly melanopsin-positive, and within the optimally infected areas, more than 60% were positive 4 wk after infection (Fig. S2 A and B). These numbers likely underestimated the AAV infection rate resulting from the sensitivity of immunostaining. After injecting AAV-expressing Cre recombinase (AAV-Cre) at a similar titer into a Rosa26-TMT reporter mouse, the AAV infected more than 90% of all RGCs (Fig. S2C). In mice with AAV-Mela injection, levels of pS6 were high in more than 40% of the RGCs (Fig. 1 F and G), higher than control mice with AAV-GFP injection. One day after nerve crush in the AAV-GFP–injected mice, pS6 levels in Tuj1-positive RGCs were reduced. In the AAV-Mela–injected mice, pS6 levels were maintained (Fig. 1 F and G). Thus, melanopsin stimulates mTOR activity in RGCs.

Fig. S2.

Melanopsin overexpression in retinas. (A) Low-magnification images of whole-mounted retinas from WT mice with intact optic nerves. The mice were injected with AAV-GFP (control) or AAV-Mela. Retinas were stained with a melanopsin antibody. (B) High-magnification images of whole-mounted retinas from WT mice with intact optic nerves. The mice were injected with AAV-GFP or AAV-Mela Retinas were stained with Tuj1 (red) and melanopsin (green) antibodies. (C) Whole-mount retinas from Rosa26-TMT mice that were injected with AAV-Cre. Retinas were stained with Tuj1 (green) and TMT (red) antibodies. Red labels RGCs that were infected with AAV-Cre. (Scale bars: A and C, 100 μm; B, 50 μm.)

Melanopsin Overexpression Promotes Optic Nerve Regeneration Through an mTORC1-Dependent Mechanism.

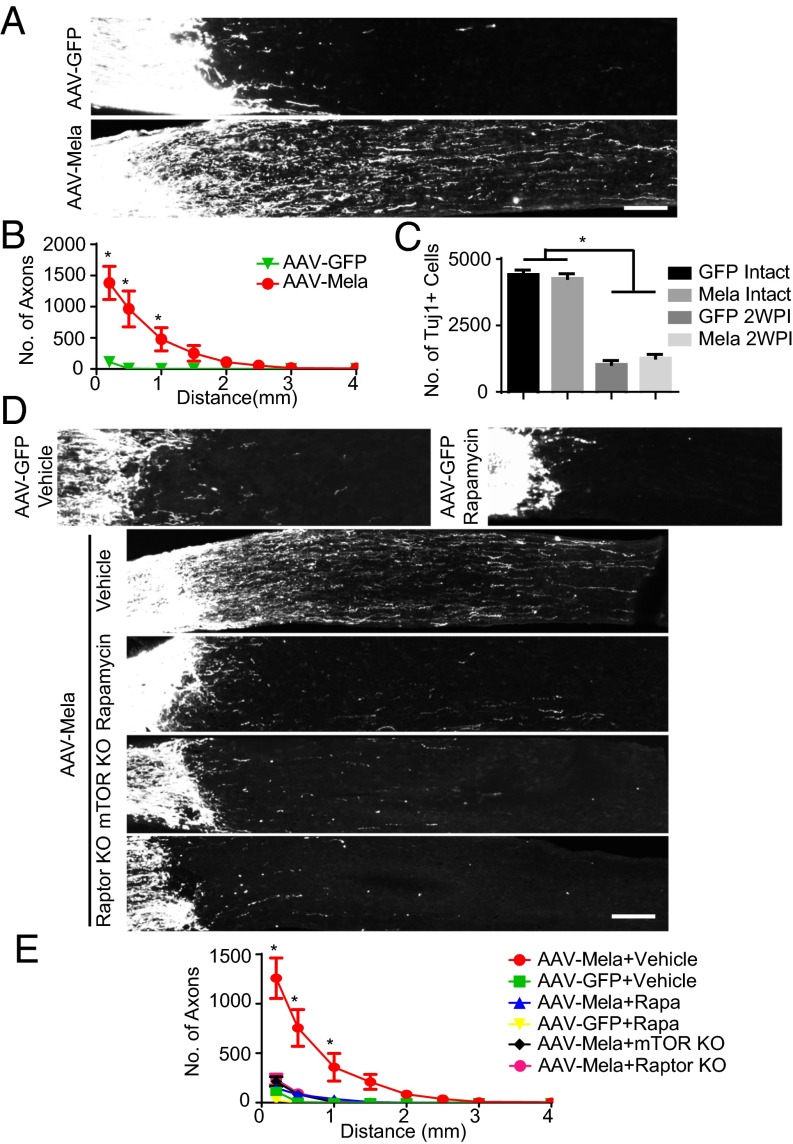

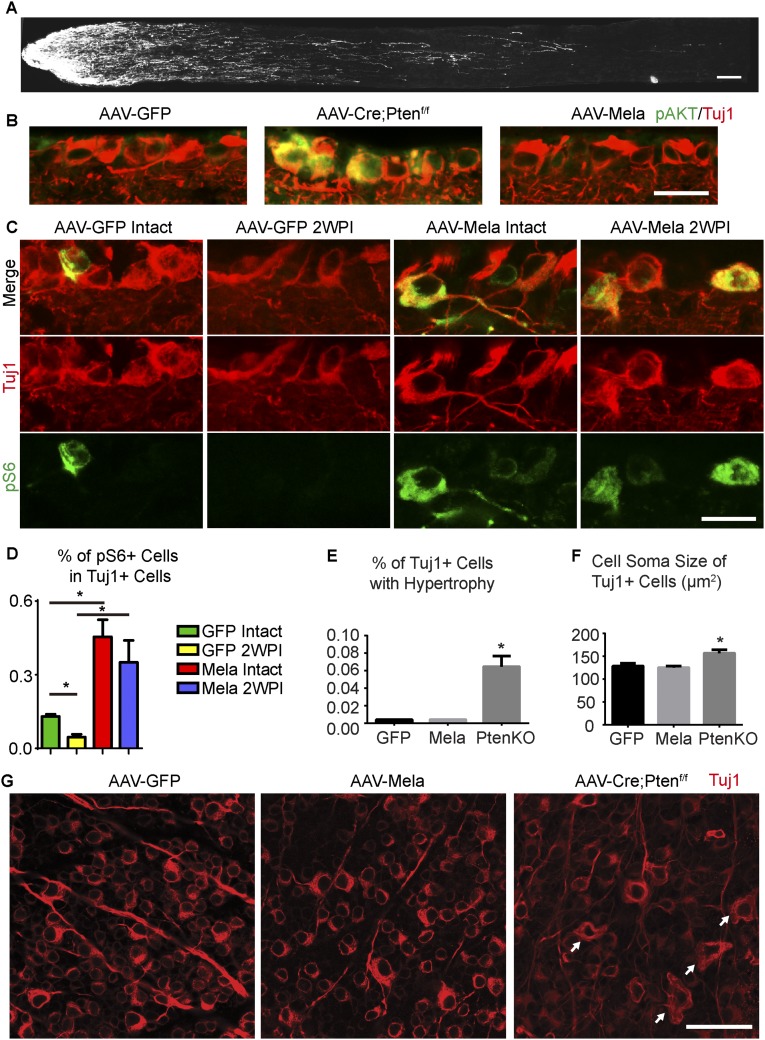

To determine whether melanopsin could promote axonal regeneration after nerve injuries, we crushed the optic nerves of mice infected with AAV-Mela. Two weeks later, we traced axons by injecting cholera toxin B conjugated with Alexa 488 (CTB) into the injured eyes. Axonal regeneration was evident in the AAV-Mela–injected mice, but not in the control mice (Fig. 2 A and B). In some cases, axons extended more than 2 mm (Fig. S3A). Tuj1 staining showed that the rates of RGC survival were similar between the two groups (Fig. 2C). The lack of survival effect may be partially explained by which phosphorylated AKT in RGCs was not enhanced by melanopsin overexpression (Fig. S3B). Levels of pS6 in Tuj1-postive RGCs were also increased at 2 wk after nerve crush (Fig. S3 C and D). Interestingly, RGCs that overexpressed melanopsin did not show hypertrophic cell bodies or a bulging morphology compared with neurons in which Pten was deleted (Fig. S3 E–G). This likely suggested that mTOR signaling boosted by melanopsin was not hyperactive but was still sufficient for growth. Thus, melanopsin overexpression promotes retinal axon regeneration after optic nerve crush.

Fig. 2.

Melanopsin overexpression promotes optic nerve regeneration through an mTORC1-dependent mechanism. (A) Sections of optic nerves containing CTB-labeled axons from WT mice at 2 wk postinjury (2WPI), injected with either AAV-GFP or AAV-Mela. (B) Quantification of regenerating axons at different distances distal to the lesion sites. *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD, six mice in each group. (C) Quantification of the densities of Tuj1+ RGCs in intact and 2WPI retinas. *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test, six mice in each group. (D) Sections of optic nerves from WT, mTOR floxed, and Raptor floxed mice at 2 wk after crush. WT mice were injected with either AAV-GFP or AAV-Mela and administered vehicle or rapamycin (6 mg/kg). Floxed mice were coinjected with AAV-Cre and AAV-Mela. (E) Quantification of regenerating axons from the six groups at different distances distal to the lesion sites. *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, five to six mice in each group. (Scale bars: A and D, 100 μm.)

Fig. S3.

Melanopsin enhances axon regeneration and pS6 expression in RGCs without inducing hypertrophy. (A) Sections of optic nerves with CTB-labeled axons from WT mice treated with AAV-Mela showing long-distance regeneration at 2 wk after crush. (B) Sections of retinas from WT mice that were injected with either AAV-Mela or AAV-GFP and from Ptenf/f mice that were injected with AAV-Cre. Retinas were stained with Tuj1 (red) and phosphorylated AKT (green) antibodies. (C) Sections of retinas from WT mice with intact optic nerves or at 2 wk postinjury (2WPI). The mice were injected with AAV-GFP or AAV-Mela. Retinas were stained with Tuj1 (red) and pS6 (green) antibodies. (D) Quantification of the percentage of Tuj1+ RGCs that express pS6. *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, three to five mice in each group. (E) Quantification of the percentage of Tuj1+ RGCs with hypertrophic morphology from WT mice that were injected with either AAV-Mela or AAV-GFP and from Ptenf/f mice that were injected with AAV-Cre. (F) Quantification of the cell soma size of Tuj1+ RGCs. *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, five mice in each group. (G) Whole-mount retinas from three groups. Retinas were isolated from mice 2 wk after optic nerve crush and stained with Tuj1 antibodies (red). Arrows indicate hypertrophic RGCs in retinas from mice with Pten deletion. (Scale bars: A, 100 μm; B and C, 15 μm; G, 50 μm.)

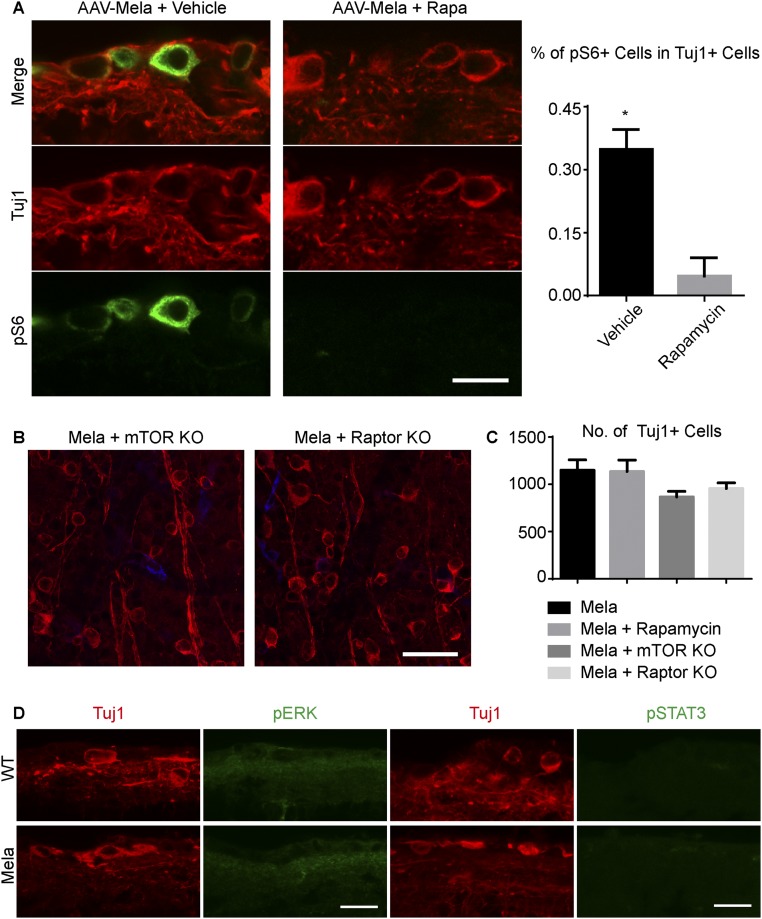

We further assessed whether mTOR activation is functionally required for the regenerative effects induced by melanopsin. Rapamycin, a potent and specific inhibitor of mTOR, suppressed the axonal regeneration promoted by melanopsin (Fig. 2 D and E), as well as the induced increase in pS6 levels (Fig. S4A). To investigate whether mTOR signaling definitively mediates axon regeneration, we took a genetic approach and inactivated the mTOR kinase, using mTOR floxed mice (15). AAV-Cre and AAV-Mela were coinjected into mTOR floxed mice. Consistent with the effect of rapamycin, mTOR KO dramatically inhibited the axonal regeneration induced by melanopsin (Fig. 2 D and E). mTOR acts through two signaling complexes; namely, mTORC1 and mTORC2. To determine whether mTORC1 mediated the regeneration, we used Raptor floxed mice. Raptor is a required component of mTORC1 signaling, and these KO mice have been used to specifically inactivate mTORC1 signaling (16). Raptor deletion in RGCs blocked regeneration to a degree similar to that observed in the mTOR KO mice (Fig. 2 D and E), indicating mTORC1 played a major role in the effect. The deletion of mTOR or Raptor in neurons that were infected by AAV-Cre was verified by the loss of pS6 signal (Fig. S4B). Either KO had a modest effect on RGC survival (Fig. S4C), but it was insufficient to account for the effect on axonal regeneration. We also examined additional signaling pathways that have been shown to increase the intrinsic growth potential of injured adult RGCs: STAT3 (17) and MEK (18). Neither the p-STAT3 nor the p-ERK staining showed a detectable difference between the two groups (Fig. S4D). Therefore, both pharmacological and genetic evidence place mTORC1 downstream of melanopsin in a molecular pathway that promotes regeneration.

Fig. S4.

Melanopsin promotes regeneration by enhancing mTOR. (A) Effect of rapamycin on mTOR expression. Images of retinal sections from WT mice that were injected with AAV-Mela at 2 wk after crush and then treated with either vehicle or rapamycin. Sections show pS6 (green) and Tuj1 (red) labeling. Quantification of the percentage of Tuj1+ RGCs that express pS6 in mice that were treated with vehicle or rapamycin. Student’s t test, *P < 0.05, three mice in each group. (B) Whole-mount retinas from mTOR floxed, and Raptor floxed mice at 2 wk after crush. Mice were coinjected with AAV-Cre and AAV-Mela. Retinas were stained with Tuj1 (red) and pS6 (green) antibodies. pS6 expression was suppressed by mTOR KO and Raptor KO. (C) Quantification of RGC survival. (D) Retinal sections from WT mice that were treated with either AAV-Mela or AAV-GFP at 2 wk after optic nerve crush. The sections were labeled with Tuj1, pERK, and pSTAT3 antibodies. (Scale bars: A, 15 μm; B, 50 μm; D, 20 μm.)

Melanopsin Promotes Comparable Axon Regeneration to Pten Inhibition.

Melanopsin overexpression activated mTOR without causing hypertrophy in RGCs (Fig. S3D), which is potentially an undesired feature developed in neurons with Pten deletion. It motivated us to compare the melanopsin effect with Pten inhibition on axon regeneration. We injected AAV-Mela, AAV-shRNA that targeted Pten (shPten), AAV-shRNA that targeted suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (Socs3) (shSocs3), or a combination of these factors into the vitreous bodies of mice and waited 3 wk. We then examined axonal regeneration 2 wk after optic nerve crush. AAV-Mela induced axonal regeneration that was comparable to that induced by shPten or shSocs3 (Fig. S5 A and B). When AAV-Mela was combined with shSocs3, but not with shPten, we observed synergistic growth that was comparable to the effect of the double knockdown of Pten and Socs3 (Fig. S5 A and B), which is consistent with a previous finding that mTOR and STAT3 coactivation in RGCs promotes sustained axon regeneration (17). In addition, AAV-Mela did not further increase the synergistic growth induced by shPten and shSocs3 (Fig. S5 A and B). Thus, melanopsin overexpression may provide an alternative strategy to Pten inhibition for axon regeneration.

Fig. S5.

Melanopsin promotes comparable axon regeneration to Pten knockdown. (A) Images of optic nerves with CTB-labeled axons from WT mice at 2 wk after crush. The mice were treated with AAV-Mela, AAV-shPten, AAV-shSocs3, or a combination of AAVs. (Scale bar, 200 μm.) (B) Quantification of optic nerves with CTB-labeled axons for all of the groups. Axon regeneration in the AAV-Mela group was comparable to that in the AAV-shPten and AAV-shSocs3 groups. AAV-Mela and AAV-shSocs3 cotreatment promoted axon regeneration that was comparable to that observed with AAV-shPten and AAV-shSocs3 cotreatment and that was greater than that observed after any of the single treatments. ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, five to six mice in each group.

Melanopsin Promotes Axon Regeneration of αRGCs.

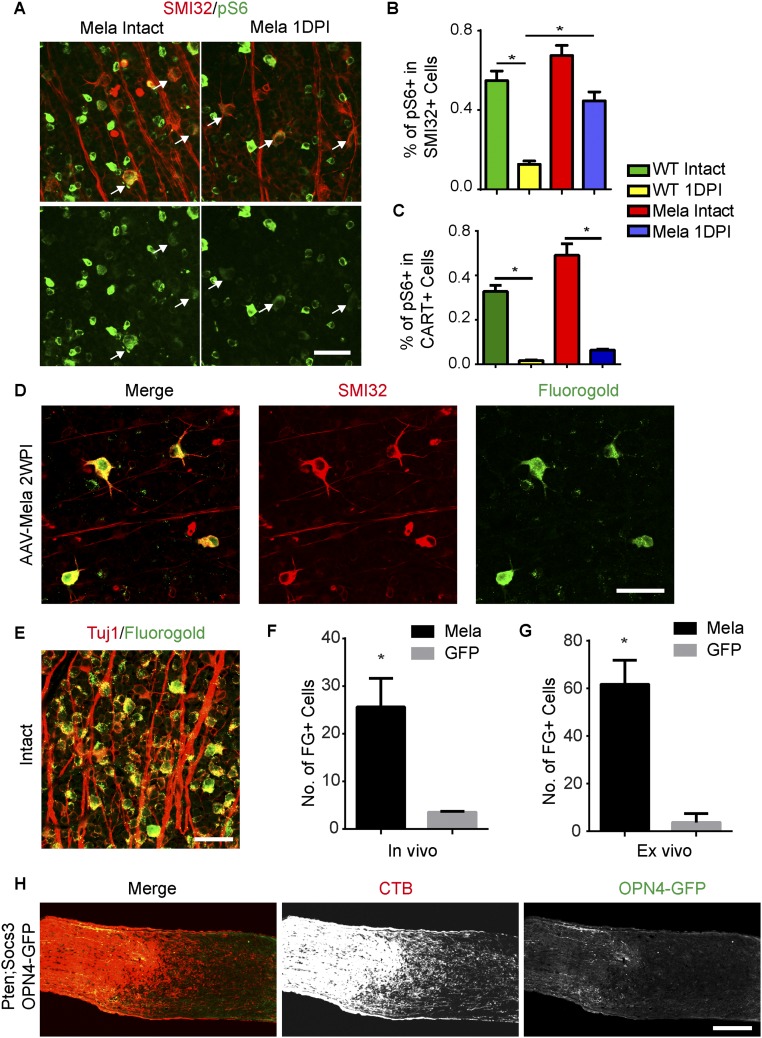

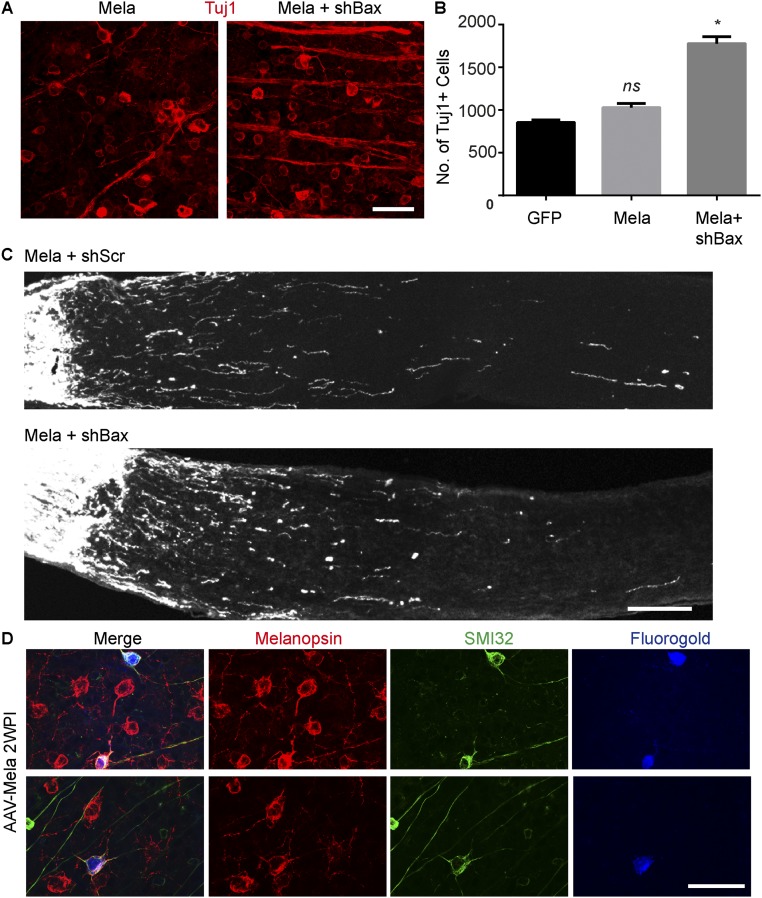

Then we investigated the cell types that regenerated their axons. The stimulation of optic nerve regeneration via Pten inhibition is confined to αRGCs (8). With melanopsin overexpression, injured αRGCs exhibited elevated pS6 levels (Fig. S6 A and B), but cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript-positive RGCs did not (Fig. S6C). We injected Fluorogold (FG) into the optic nerve distal to the lesion site to label RGCs with axon regeneration, as previously described (9). In animals with AAV-Mela, 95% of the labeled RGCs were positively stained with SMI32 (Fig. S6 D–F). In addition, a similar result (92%) was achieved by doing ex vivo labeling in isolated retinas (Fig. S6G). Thus, the majority of regenerating fibers were from SMI32+ αRGCs. However, it raised a question of why M1 ipRGCs, which express a high level of melanopsin, do not regenerate after injury. By using Ptenf/f;Socs3f/f;Opn4-GFP mice, we showed that deletion of both Pten and Socs3 robustly promoted CTB-labeled axons beyond the lesion site but did not drive GFP+ axons to regenerate (Fig. S6H). The mechanism remains unclear. Then, we assessed whether the effect of melanopsin was cell autonomous. AAV-shRNA against Bax (AAV-shBax) significantly enhances the survival of RGCs (Fig. S7 A and B), but not the regeneration induced by melanopsin (Fig. S7C). We also quantified the percentage of retrograde-labeled RGCs expressing melanopsin after optic nerve crush. More than 95% of labeled RGCs expressed both melanopsin and SMI32. Because M4 ipRGC (On αRGCs) cannot be detected by typical immunostaining of melanopsin, it suggested that the melanopsin expression came from AAV-Mela. The results support that the effect of melanopsin overexpression is most likely cell autonomous.

Fig. S6.

Melanopsin promotes axon regeneration of αRGCs. (A) Whole-mount retinas from WT mice injected with AAV-GFP or AAV-Mela with intact optic nerves or 1DPI. Retinas were stained with SMI32 (red) and pS6 (green) antibodies. (Scale bar: 50 μm.) (B) Quantification of percentages of SMI32+ RGCs expressing pS6. (C) Quantification of percentages of cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript-positive RGCs expressing pS6. *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, three to five mice in each group. (D) A whole-mount retina from a mouse with AAV-Mela showing SMI32+ RGCs retrogradely labeled with FG by direct injection into the optic nerve in vivo. SMI32 was positively stained in 95% and 92% of FG+ RGCs for the in vivo and ex vivo labeling, respectively. (E) A whole-mount retina from an intact mouse showing that FG nonselectively labeled Tuj1+ RGCs. (F) For the in vivo labeling, quantification of numbers of FG+ cells per retina in mice injected with AAV-Mela or AAV-GFP. Student’s t test, *P < 0.05, four mice in each group. (G) For the ex vivo labeling, quantification of numbers of FG+ cells per retina in mice injected with AAV-Mela or AAV-GFP. Student’s t test, *P < 0.05, three mice in each group. (H) Images of an injured optic nerve with CTB-labeled axons from Ptenf/f;Socs3f/f;Opn4-GFP mice injected with AAV-Cre and AAV-Mela. GFP+ axons did not regenerate and were not colocalized with CTB+ axons beyond the lesion. (Scale bars: A, D, and E, 50 μm; H, 100 μm.)

Fig. S7.

The effect of melanopsin overexpression is cell autonomous. (A) Whole-mount retinas from mice at 2 wk after crush. Mice were coinjected with AAV-shBax and AAV-Mela. Retinas were stained with Tuj1 (red) antibody. (B) Quantification of RGC survival in three groups. *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, three mice in each group. (C) Sections of optic nerves from mice injected with AAV-Mela together with AAV-shRNA-scramble (shScr) or AAV-shRNA-Bax (shBax). (D) Whole-mount retinas from mice with AAV-Mela showing SMI32+ and Melanopsin+ RGCs retrogradely labeled with FG by direct injection into the optic nerve in vivo. SMI32 and melanopsin were costained in 95% of FG+ RGCs. (Scale bars: A, and D, 50 μm; C, 100 μm.)

Melanopsin Stimulates Regeneration in a Light-Dependent Manner.

Next, we investigated the mechanism or mechanisms that melanopsin activates mTOR.

Because melanopsin is a light-sensitive G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) molecule (19), we tested the idea that light stimulation may be required for melanopsin to maintain mTOR. Before assessing the effect of light on RGCs that overexpressed melanopsin, we began our investigation in normal RGCs. We dark-adapted Opn4-GFP mice for 1 d and then stained retinas for pS6. In dark-adapted retinas, ∼6% of total RGCs expressed high levels of pS6 versus ∼10% in mice under normal light conditions, and few if any GFP+ ipRGCs maintained high levels of pS6 (Fig. S8 A and B). In contrast, pS6 levels in the αRGCs were not affected by dark adaption (Fig. S8 C and D). Dark adaptation and axotomy suppressed pS6 in M1–M3 RGCs and αRGCs, respectively, suggesting two different mechanisms regulating neuronal mTOR. These findings were also consistent with the notion that pS6 was dramatically down-regulated in injured ipRGCs in Opn4 KO mice, indicating that melanopsin may function as a photo transducer to mediate mTOR signaling in M1–M3 ipRGCs. Thus, melanopsin maintains high pS6 levels in M1–M3 ipRGCs in a light-dependent manner.

Fig. S8.

Melanopsin stimulates mTOR in a light-dependent manner. (A) Whole-mount retinas from intact Opn4-GFP mice housed under a normal 12:12 light–dark cycle (NC) or a 12:12 dark–dark cycle (DD). Retinas were stained with Tuj1 (red) and pS6 (blue) antibodies. GFP (green) labels M1–M3 ipRGCs. (B) Quantification of the percentages of GFP+ ipRGCs that express pS6 for the two light conditions. *P < 0.05, Student’s t test, three mice in each group. (C) Whole-mount retinas from intact WT mice housed under a normal 12:12 light–dark cycle (NC) or a 12:12 dark–dark cycle (DD). Retinas were labeled with SMI32 (red) and pS6 (blue) antibodies. (D) Quantification of the percentage of SMI32+ αRGCs expressing pS6 for the two light conditions. (E) Quantification of RGC survival for WT mice housed under NC or DD at 2 wk after crush. The mice were injected with AAV-Mela 4 wk before injury. (F) Quantification of the percentage of SMI32+ αRGCs expressing pS6 at a different time after continuous light stimulation in injured mice with AAV-Mela or AAV-GFP injection. Mice were dark-adapted for 24 h before stimulation. (G) Sections of optic nerves with CTB-labeled axons from WT mice injected with AAV-shPten and crush. Mice were housed under NC or DD for 2 wk after optic nerve crush. DD did not suppress axon regeneration. Optic nerve images were collected on a Zeiss LSM 710 laser scanning confocal microscope with a 10× objective, and tiled together by using the automatic stitching function of ZEN 2009. The images with the CTB channel were converted to grayscale and exported. (Scale bars: A and C, 50 μm; G, 100 μm.)

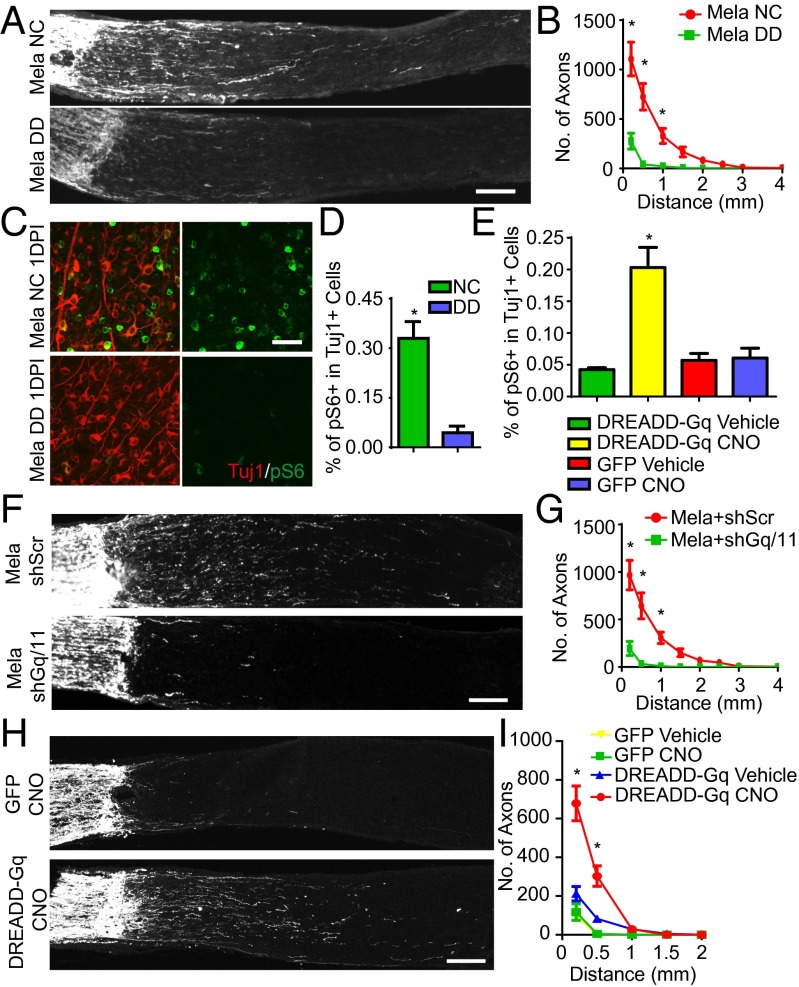

To determine whether light could also affect the mTOR activation and axon regeneration induced by melanopsin overexpression, we infected RGCs with AAV-Mela, crushed the optic nerves, and put the mice in the dark. Deprivation of light blocked regeneration, as shown by CTB tracing 2 wk later (Fig. 3 A and B). The pS6 levels, which were normally elevated by melanopsin, were also largely suppressed by darkness (Fig. 3 C and D). RGC survival was not affected (Fig. S8E). Continuous light stimulation enhanced and maintained mTOR activity in injured SMI32+ RGCs in mice with AAV-Mela, but not in control mice (Fig. S8F). In contrast, deprivation of light did not suppress axon regeneration induced by Pten inhibition (Fig. S8G). These data suggest light may function upstream of melanopsin-mediated signaling to promote regeneration.

Fig. 3.

Axon regeneration induced by melanopsin requires light stimulation and Gq/11 signaling. (A) Sections of optic nerves from WT mice housed under NC or DD at 2 wk after crush, with AAV-Mela injection. (B) Quantification of regenerating axons at different distances distal to the lesion sites. *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD, six mice in each group. (C) Whole-mount retinas at 1DPI from AAV-Mela–injected mice under NC or DD conditions, with Tuj1 (red) and pS6 (green) staining. (D) Quantification of the percentage of Tuj1+ RGCs expressing pS6 for the two light conditions. *P < 0.05, Student’s t test, three mice in each group. (E) Quantification of the percentages of Tuj1+ RGCs expressing pS6 in retinas from WT mice that were injected with AAV-DREADD-Gq or AAV-GFP and treated with vehicle or CNO (5 mg/kg). *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, five to six mice in each group. (F) Sections of optic nerves from mice injected with AAV-Mela together with AAV-shRNA-scramble (shSc) or AAV-shRNA-Gq and -G11 (shGq/11). (G) Quantification of regenerating axons at different distances distal to the lesion sites. *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD, six mice in each group. (H) Images of optic nerves from WT mice injected with AAV-DREADD-Gq or AAV-GFP at 2 wk after crush and treated with either saline or CNO (5 mg/kg) twice daily. (I) Quantification of regenerating axons at different distances distal to the lesion sites. *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, five to six mice in each group. Optic nerve images were collected on a Zeiss LSM 710 laser scanning confocal microscope with a 10× objective, and tiled together by using the automatic stitching function of ZEN 2009. The images with the CTB channel were converted to grayscale and exported. (Scale bars: A, F, H, 100 μm; C, 50 μm.)

Melanopsin Promotes mTOR-Dependent Regeneration by Activating Gq/11 Signaling.

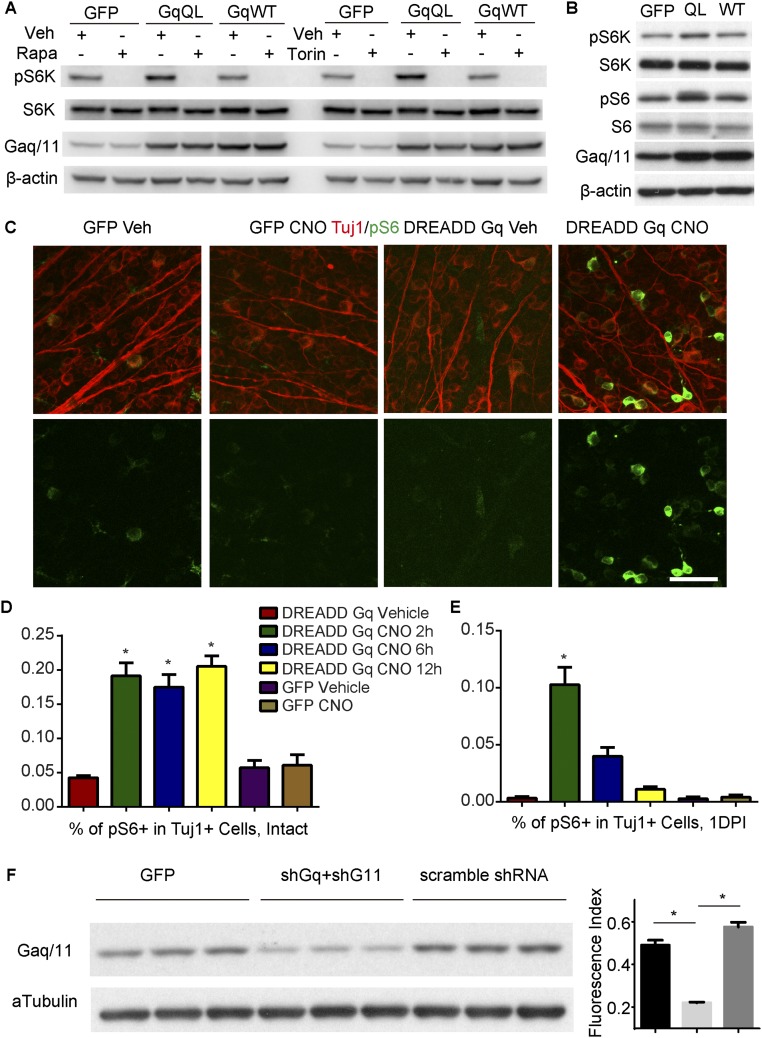

Melanopsin has been experimentally shown to require G protein signaling for its light responsiveness (20). We therefore examined whether melanopsin regulates mTOR through the canonical GPCR signaling pathway. The endogenous G proteins that are downstream of melanopsin in ipRGCs are unclear, but in heterologous expression systems, melanopsin may signal primarily by coupling with G protein or proteins of the Gq family upon light stimulation (20). Then we tested whether Gq/11 signaling enhances mTOR activation. In Neuro2A cells, compared with GFP or Gq WT transfection, transfection with constitutively active Gq mutants (GqQL) increased phosphorylated P70 S6 kinase (pS6K) levels; this effect was blocked by rapamycin or torin (Fig. S9A), suggesting mTORC1 activation. The pS6 level was also increased (Fig. S9B). To mimic the physiological conditions of Gq/11 signaling in RGCs, we took a chemogenetic approach. A mutant M3 muscarinic GPCR hM3Dq, which is also called a designer receptor exclusively activated by a designer drug (DREADD-Gq), can be used to selectively activate Gq/11 signaling when expressed in vivo. This Gq/11-coupled designer GPCR cannot be activated by its natural ligand (acetylcholine), but becomes activated by clozapine N-oxide (CNO), an otherwise pharmacologically inert compound (21). We injected AAVs expressing DREADD-Gq (AAV-DREADD-Gq) into the eyes of WT mice. Four weeks later, mice were dark-adapted for 24 h before we examined the effect of CNO. In AAV-DREADD-Gq-injected mice without an injury, pS6 signaling was increased in RGCs 2 h after the administration of CNO and sustained at least to 12 h (Fig. 3E and Fig. S9 C and D). After optic nerve injury, the pS6 level was elevated at 2 h but decreased at 6 h, and returned the basal level at 12 h (Fig. S9E). Then we tested whether Gq/11 signaling was required for the melanopsin-mediated axon regeneration. The heterotrimeric G proteins Gq and G11 are often functionally redundant. We injected two AAVs, each of which encoded an shRNA directed against Gnaq (shGq) or Gna11 (shG11), together with AAV-Mela. We validated the efficacy of the shRNAs by Western blot analysis (Fig. S9F). Gq and G11 knockdown significantly suppressed the axon regeneration normally induced by melanopsin overexpression (Fig. 3 F and G). To assess whether activating Gq/11 signaling enhances axonal regeneration, we injected AAV-DREADD-Gq, performed optic nerve crush, and intraperitoneally administered CNO (5 mg/kg) into mice twice daily for 2 wk. In AAV-DREADD-Gq–injected mice, CNO treatment resulted in a significant increase in axonal growth compared with control groups. Neither CNO nor AAV-DREADD-Gq with vehicle has any growth-promoting effect (Fig. 3 H and I). Thus, Gq/11 may function as a downstream effector of melanopsin upon light stimulation to mediate axon regeneration.

Fig. S9.

Gq signaling enhances mTOR activation. (A) Immunoblots for pS6K in Neuro2a cells transfected with GFP, Gq with constitutive activity (Gq QL), and Gq WT. Cells were treated vehicle, rapamycin (Rapa), or Torin. (B) Immunoblots for pS6 in Neuro2a cells transfected with GFP, Gq QL, and Gq WT. (C) Whole-mount retinas from WT mice that were injected with AAV-DREADD-Gq or AAV-GFP and treated with CNO. Retinas were stained with Tuj1 (red) and pS6 (green) antibodies. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (D) Quantification of the percentages of Tuj1+ RGCs expressing pS6 in retinas from intact WT mice that were injected with AAV-DREADD-Gq or AAV-GFP and treated with vehicle or CNO (5 mg/kg). Mice were dark-adapted for 24 h before CNO injection and killed at different times after injection. (E) Quantification of the percentages of Tuj1+ RGCs expressing pS6 in retinas from injured WT mice that were injected with AAV-DREADD-Gq or AAV-GFP and treated with vehicle or CNO (5 mg/kg). Mice were dark-adapted for 24 h before CNO injection and killed at different times after injection. *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, five to six mice in each group. (F) Immunoblots and quantification for Gaq/11 in N2a cells transfected with in GFP, shRNAs against Gnaq (shGq) and Gna11 (shG11), and scramble shRNA.

Neuronal Activity in RGCs Modulated by Melanopsin Overexpression Is Essential for Regeneration.

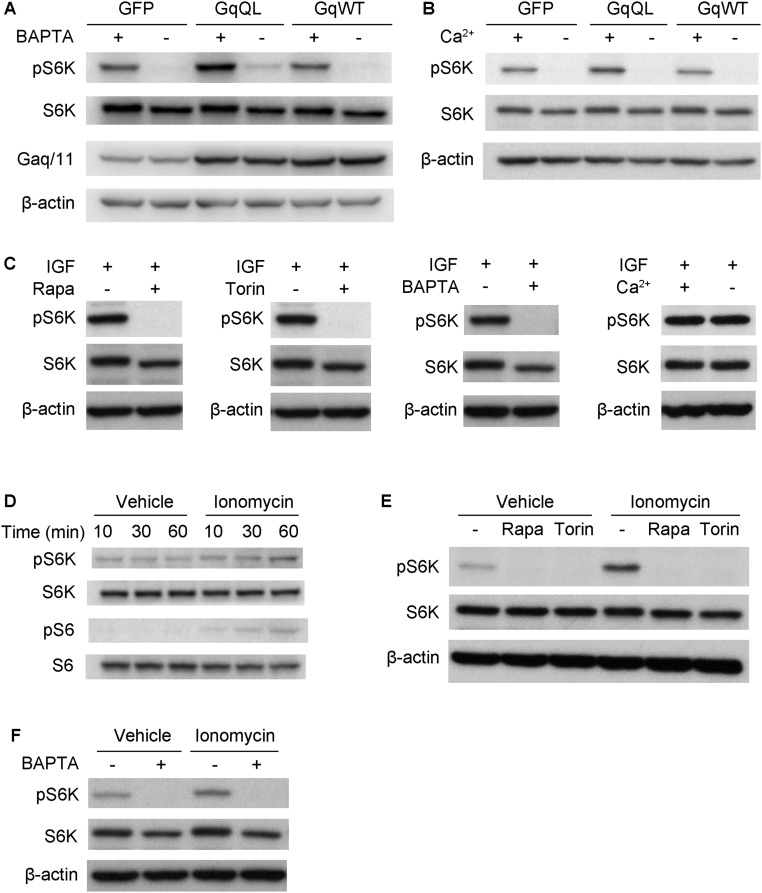

We next asked how Gq/11 signaling enhances mTOR signaling. Orexin/GPCR signaling activates mTOR via calcium influx (22). Upon light stimulation, expression of melanopsin in RGCs can result in neuronal depolarization, the triggering of action potentials, and calcium influx into neurons. We investigated whether calcium plays a role in Gq/11-stimulated mTORC1 activation. In Neuro2A cells, the application of BAPTA/AM (BAPTA), a cell-permeable calcium chelator, to the growth media diminished the S6K phosphorylation that is normally induced by constitutive Gq activation (Fig. S10A). To determine whether extracellular calcium is essential for Gq/11 signaling to mTORC1, we treated Neuro2A cells with media that contained or lacked Ca2+. The results showed that extracellular Ca2+ enhanced Gq/11 but not insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-induced S6K phosphorylation (Fig. S10 A–C). To determine whether calcium influx was sufficient to activate mTORC1, we incubated Neuro2A cells with ionomycin that triggers extracellular calcium influx. Ionomycin induced the phosphorylation of S6K and S6 (Fig. S10D), and the effect was abolished by treatment with rapamycin or torin (Fig. S10E). This calcium-stimulated S6K phosphorylation was also abolished by treatment with BAPTA (Fig. S10F). Taken together, these results indicate that Gq/11 signaling enhances mTOR via calcium influx.

Fig. S10.

Gq signaling activates mTOR via calcium influx. (A and B) Neuro2a cells were transfected with GFP, Gq QL, and Gq WT and treated with 20 μM BAPTA or calcium-free medium 1 h before lysis. (C) Neuro2a cells were stimulated with IGF for 10 min before lysis, together with 10 μM rapamycin, 100 μM Torin, 20 μM BAPTA, or calcium-free medium. Each blocker was added 10 min before IGF stimulation. (D) Neuro2a cells were stimulated with 0.75 μM Ionomycin for up to 60 min. (E) Neuro2a cells stimulated with 0.75 μM Ionomycin for 60 min, together with rapamycin or Torin. Each blocker was added 10 min before stimulation. (F) Cells were stimulated with Ionomycin for 60 min before lysis, together with BAPTA. Western blot analysis was performed using pS6K or pS6.

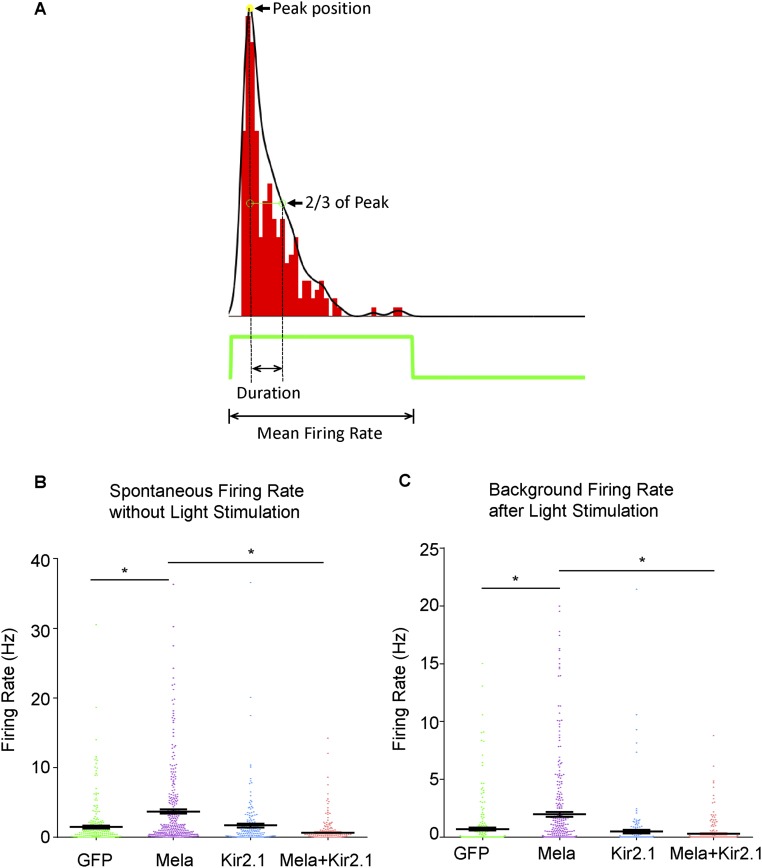

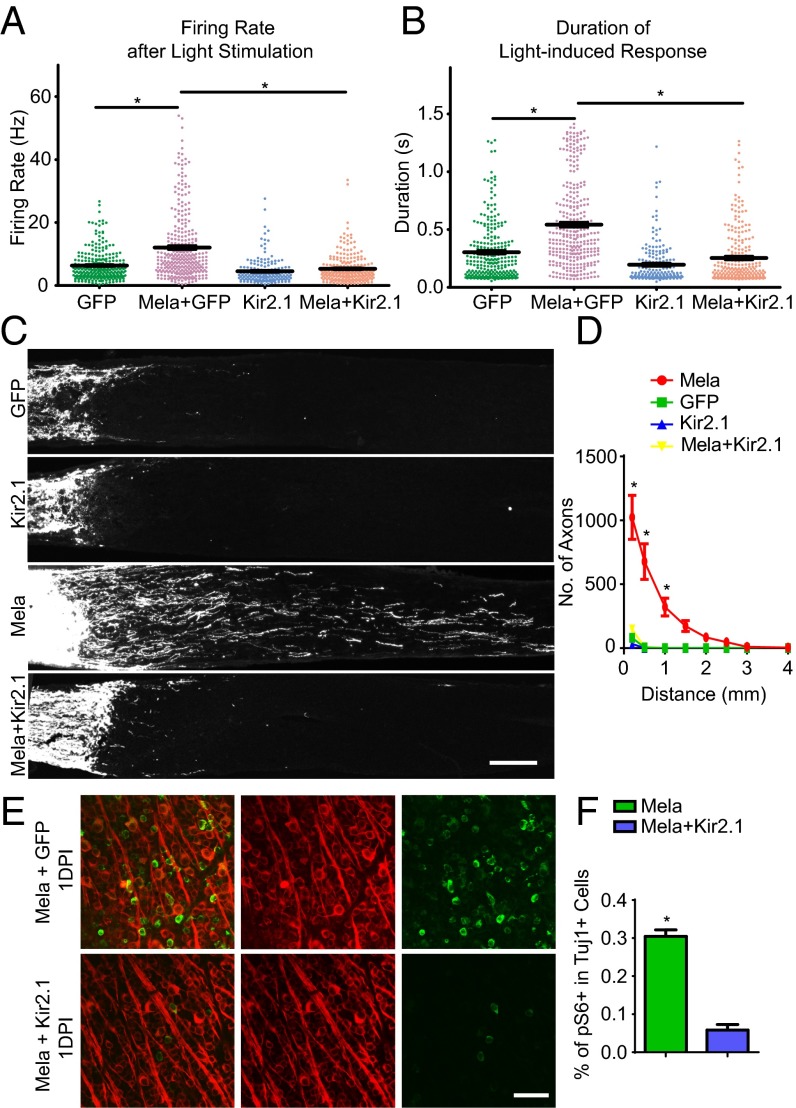

Although we showed that light-induced Gq/11 signaling is required for melanopsin to activate mTORC1, and the effect is related to calcium signaling, it remained unclear how mTORC1 signaling could be sustained for weeks for axon regeneration in vivo. Neuronal activity has been shown to regulate S6 phosphorylation in animals, and different activity-related stimuli may induce pS6 expression with varying efficiency and kinetics and for varying durations (23); furthermore, DREADD-Gq has been used to enhance neuronal firing in animals (21). We then asked whether neuronal activity could mediate the regeneration effect. To test whether melanopsin overexpression modulated neuronal activity in RGCs, retinas were isolated and presented with periodic light flashes. Action potentials from RGCs were recorded extracellularly with a multielectrode array (MEA). Population data revealed that both the response amplitude, as measured by average firing rate, and the response duration (Fig. S11A) were significantly higher in retinas treated with AAV-Mela compared with control retinas (Fig. 4 A and B). Spontaneous firing, both after dark adaptation and under moderate illumination, was also enhanced (Fig. S11 B and C). This increase was returned to control levels by the coinjection of AAV-expressing Kir2.1 (Fig. 4 A and B), an inward-rectifying potassium ion channel that causes hyperpolarization and a substantial decrease in neural activity (24). In the optic nerve crush model, AAV-Kir2.1 significantly inhibited the axon regeneration that was normally stimulated by melanopsin (Fig. 4 C and D). It also suppressed pS6 expression in RGCs (Fig. 4 E and F), indicating that mTOR signaling in RGCs is activity-dependent. Taken together, these results suggest that melanopsin boosts axon regeneration by enhancing mTORC1 in a neuronal activity-dependent manner.

Fig. S11.

Enhanced neuronal activity in RGCs by melanopsin overexpression. (A) A diagram showing the calculation of PSTH The width of the PSTH above one-third of its peak value is taken as the duration of the response. Total number of spikes 0–1.5 s after light onset (for ON cells) or offset (for OFF cells) was used to calculate average response firing rate. (B) Spontaneous firing rates of RGCs recorded from the retinas of mice that were injected with AAV-GFP, AAV-Mela + AAV-GFP, AAV-Kir2.1 + AAV-GFP, or AAV-Mela + AAV-Kir2.1 + AAV-GFP. Spontaneous firing rates were calculated as mean spiking rates during a 10-min no-stimulus MEA recording after at least 1-h dark adaptation. The spontaneous firing rate of the AAV-Mela + AAV-GFP group was significantly higher than the control group (AAV-GFP). Kir2.1 decreased the enhanced spontaneous firing rate. (C) The background firing rates of recorded RGCs from four groups. The background firing rates of recorded cells were calculated as mean spiking rates of the last 0.15 s of related periods. For ON cells, on periods were used, and the same for OFF cells, but for ON-OFF cells, ON and OFF periods were averaged. GFP: three mice, four retinas, 261 cells; Mela + GFP: three mice, four retinas, 317 cells; Kir2.1 + GFP: two mice, four retinas, 181 cells; Mela + Kir2.1 + GFP: two mice, four retinas, 249 cells. *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test.

Fig. 4.

Neuronal activity mediates mTORC1 and regeneration induced by melanopsin. (A) Average firing rates of RGCs in response to periodic light flashes. The RGCs were recorded using multielectrode array from the retinas of mice that were injected with AAV-GFP, AAV-Mela + AAV-GFP, AAV-Kir2.1 + AAV-GFP, or AAV-Mela + AAV-Kir2.1 + AAV-GFP. The light stimulus was a spot flashing white (ON period) and black (OFF period) for 1.5 s each on a gray background and repeated several times. (B) Duration of RGCs’ light response during ON and OFF periods in the same recordings as in A. GFP: three mice, four retinas, 261 cells; Opn4+GFP: three mice, four retinas, 317 cells; Kir2.1+GFP: two mice, four retinas, 181 cells; Opn4+Kir2.1+GFP: two mice, four retinas, 249 cells. *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. (C) Sections of optic nerves from WT mice at 2 wk after crush, injected with AAV-GFP, AAV-Kir2.1, AAV-Mela, and AAV-Mela + AAV-Kir2.1. (D) Quantification of regenerating axons at different distances distal to the lesion sites. *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD, six mice in each group. (E) Whole-mount retinas at 1DPI from mice that were injected with AAV-Mela + AAV-GFP or AAV-Kir2.1, with Tuj1 (red) and pS6 (green) staining. (F) Quantification of the percentages of Tuj1+ RGCs expressing pS6. *P < 0.05, Student’s t test, three mice in each group. (Scale bars: C, 100 μm; E, 50 μm.)

Discussion

We showed that injured M1–M3 ipRGCs maintain mTOR by expressing a high level of melanopsin. Melanopsin overexpression in RGCs promoted axonal regeneration after optic nerve crush by activating mTORC1 to an extent comparable to that induced by Pten inhibition. Light, Gq/11 signaling, and neuronal activity enhanced mTOR and axon regeneration. Furthermore, specifically activated Gq/11 signaling in RGCs through DREADD by systematic delivery of CNO enhances the regrowth. These findings therefore provide a rationale for modulating neuronal activity through GPCRs to stimulate axonal regeneration after CNS injuries.

Various GPCRs are expressed on the surface of neurons, and they mediate physiological responses to hormones, neurotransmitters, and environmental stimulants. GPCRs have multiple effects on neuronal development, including neuronal differentiation, axon guidance, and targeting (25). In Caenorhabditis elegans, endogenous arachidonyl ethanolamide activates Go signaling and inhibits axonal regeneration by antagonizing the Gq-PKC-JNK pathway (26). In our study, we showed that light activates melanopsin and the Gq/11 signaling to stimulate mTOR. It is most likely that mTOR depends on an elevation in cytoplasmic calcium. Melanopsin activates Gq/11 signaling that subsequently increases neuronal activity and calcium influx to a degree that may be necessary to sustain long-term mTOR activation in RGCs without causing cell death. Indeed, a group of RGCs showed a higher frequency of firing above 20 Hz after melanopsin overexpression. Although we lack direct evidence that the regenerated axons belong to the neurons that are more active, silencing these neurons suppresses mTOR activation and axonal regeneration. During development, neuronal activity is essential for axon growth and wiring (27). In vitro, postnatal RGCs respond to growth factors by elongating axons after depolarization (28). In adults, electrical stimulation has been shown to promote the regeneration of crushed optic nerves over short distances (29). Optogenetic stimulation enhances axon regeneration in worms after laser axotomy by regulating localized calcium release (29). Our findings may provide a mechanistic link between axon regeneration and elevated neuronal activity. mTOR activation may also serve as a readout for the optimum electrical or optogenetic stimulation to promote regrowth in vivo.

Our results also raise the question of why M1 ipRGCs do not regenerate after injury even though they survive axotomy and express a high level of melanopsin. Duan et al. (8) indirectly showed that axons of M1 ipRGCs are not regenerated after Pten inhibition, suggesting that enhancing mTOR is not sufficient to boost the growth of M1 ipRGCs. We showed that Opn4-GFP+ axons also did not regenerate even after deleting both Pten and Socs3 genes. It may suggest that other mechanisms than mTOR or Stat3 regulate the axon regeneration in M1 ipRGCs, because they can regenerate when presented with a peripheral graft (30). Interestingly, M1 ipRGCs have intraretinal axon collaterals that terminate in the inner plexiform layer of the retina (31). In dorsal root ganglion neurons, a surviving intact branch suppresses axon regeneration after a laser-induced lesion (32). The suppression effect from intact collaterals could partially account for the lack of regeneration in M1 ipRGCs in the inhibitory environment.

Pten inhibition activates mTOR and promotes corticospinal tract regeneration after spinal cord injury (33, 34), indicating the translational potential of this strategy. However, Pten inhibition also activates additional pathways that likely contribute to its oncogenic activity. In the retina, melanopsin does not cause hypertrophy in RGCs, suggesting that neuronal mTOR is not hyperactive in these cells, as it is in neurons with Pten deletion, yet melanopsin-induced mTOR was sufficient for regrowth. Melanopsin may provide an alternative method that bypasses this potential risk with Pten inhibition. Overall, by identifying melanopsin as an mTOR booster through Gq/11 signaling and neuronal activity, our study provides a strategy to promote axon regeneration, and also an approach to search for mTOR activators in different types of neurons.

Materials and Methods

All experimental procedures were performed in compliance with animal protocols that were approved by the Animal and Plant Care Facility at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Details on all experimental procedures used in this study, including animals, AAV construction, surgeries, tissue processing, immunostaining, quantification, cell culture, electrophysiology, and statistics can be found in the SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

Animals.

Rosa26-TMT, mTORf/f (15), Raptorf/f (16) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. Opn4-GFP mice (12) were obtained from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center, an NIH funded strain repository, and the strain was donated by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke funded Gene Expression Nervous System Atlas (GENSAT) bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) transgenic project. Opn4-Cre mice (13) were obtained from S. Hattar (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore). Ptenf/f (9) and Ptenf/f;Socs3f/f (17) mice were obtained from Z. He (Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston). C57/B6 mice were used as WT. We crossed to generate Opn4Cre/+;TMT, Opn4Cre/Cre;TMT, and Ptenf/f;Socs3f/f;Opn4-GFP mice. All experimental procedures were performed in compliance with animal protocols that were approved by the Animal and Plant Care Facility at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

AAV Construction.

We used AAV serotype 2/2 to overexpress melanopsin (14), Cre recombinase (9), DREADD-Gq (Addgene 50463, a gift from Bryan Roth), Kir2.1 (Addgene 60598, a gift from Massimo Scanziani), and GFP. To knock down the expression of Pten, Socs3, Gnaq, or Gna11, shRNAs were inserted into an AAV-U6 expression vector. To determine the interference efficiency, the target gene was cloned into a luciferase reporter vector. After cotransfection of the shRNA and the relevant luciferase reporter vector into HEK293 cells, a luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) was used to detect silencing efficiency. The virus titer was ∼1013 GC/mL.

Surgeries.

For all surgical procedures, mice were anesthetized with ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) and received Meloxicam (1 mg/kg) as analgesia after the operation. Eye ointment was applied to protect the cornea during and after surgery. The eye injection and optic nerve crush were performed as previously described (9). We injected 2 μL into the vitreous bodies of 5- to 6-wk-old B6 mice, using a glass micropipette coupled to a Hamilton microsyringe. Four weeks after the mice were injected with AAVs, the left optic nerve was gently exposed by making an incision on the conjunctiva. Then the nerve was crushed with jeweler’s forceps (Dumont #5; Fine Science Tools) for 2 s at a point ∼1 mm behind the optic disk. The mice were kept alive for 1 d or for 2 wk before they were killed for tissue analysis. For light deprivation, mice were housed in a dark chamber. At various points during the experiment, the dark chamber was monitored for exposure. Mice were killed during the daytime. To suppress mTOR in RGCs, fresh-prepared rapamycin (6 mg/kg) or vehicle was administered by i.p. injection every other day, starting 1 d before the nerve was crushed. To detect mTOR activation in RGCs by DREADD-Gq, CNO (5 mg/kg/day) or vehicle was administered by i.p. injection. To visualize RGC axons in the optic nerve, 2 μL CTB (2 μg/μL, Invitrogen) was injected into the vitreous body 2 d before the mice were killed. In each mouse, the completeness of optic nerve crush was verified by showing that anterograde tracing did not reach the superior colliculus. Axons were not found in the superior colliculus in any of the mice that were examined.

Retrograde Labeling of Regenerated RGCs.

In in vivo labeling, 2 wk after the optic nerve crush, mice were anesthetized and placed in a stereotaxic holder. After exposure of the crushed optic nerve through a superior temporal intraorbital approach, we slowly injected FG (10 nL, 5% wt/vol) into the optic nerve ∼2 mm distal to the lesion site by using a pulled-glass micropipette attached to a Hamilton syringe. After 24 h, the animals were perfused with paraformaldehyde (PFA), and the whole-mount retinas were dissected for examination and staining of SMI32 and melanopsin.

Ex Vivo Labeling.

Two weeks after the optic nerve crush, mice were anesthetized, and eyes were dissected and submerged in oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid. The optic nerve was trimmed to 2 mm in length. Under dissection microscope, a tiny amount of FG powder (1–2 μg) was quickly and carefully placed to the nerve ending. After 6 h, samples were fixed with PFA for examination and staining of SMI32 and melanopsin.

Immunofluorescence Staining of Retinas and Optic Nerves.

Mice were given a lethal dose of anesthetic and perfused transcardially with PBS followed by 4% (wt/vol) PFA. Eyes and optic nerves were dissected and postfixed in 4% (wt/vol) PFA overnight at 4 °C. Tissues were cryoprotected via sucrose with increasing concentrations. After embedding into Optimal Cutting Temperature compound, the samples were frozen by dry ice and sectioned at –20 °C (25 μm for eyecups and 8 μm for optic nerves). All sections were blocked in 4% (vol/vol) normal serum and 1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h and incubated in the primary antibodies diluted in the same solution overnight at 4 °C. After being washed three times by PBS, appropriate secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, 1:500) were applied for 1–2 h at room temperature for staining. After being washed three times, sections were mounted onto glass slides (Superfrost Plus, Fisherbrand) and examined under an epifluorescence (Nikon, TE2000) or confocal microscope (Zeiss, LSM Meta710). The antibodies against the different markers included pS6, pSTAT3, pERK (Cell Signaling), Tuj1, SMI32 (Covance), melanopsin (Advanced Targeting System), and GFP (Life Technologies).

Quantification.

The total number of RGCs, as well as the number of melanopsin-positive RGCs, were determined by whole-mount retina staining. A mouse Tuj1 antibody was combined with melanopsin staining to detect RGCs. Twelve images (three for each quarter, covering peripheral to central regions of the retina) from each retina were captured under a confocal microscope (400×). An individual who was blind to the treatments counted the Tuj1-positive cells. To detect traced axons after optic nerve crush, longitudinal sections of optic nerves were serially collected. Coronal sections of eyecups were collected and stained by pS6 antibody combined with Tuj1 or SMI32 antibody. Every eight sections were taken for quantification. A cell with the staining intensity higher than five folds background staining was considered as a positive stained cell. Cell numbers were counted manually in a blinded fashion.

To analyze the extent of axon regeneration in the optic nerve, the number of axons that passed through distance d from the lesion site was estimated using the following formula: , where r is equal to half the width of the nerve at the counting site, the average number of axons per millimeter is equal to the average of (axon number)/(nerve width) in four sections per animal, and t is equal to the section thickness (8 μm). Axons were manually counted in a blinded fashion.

Cell Culture and Western Blot.

For the Gq experiment, Neuro2A cells were cultured on 12-well plates to about 70% confluence before transfection. Cells were transfected with 1 μg GqQL, GqWT, or GFP plasmid by Lipofectamine 3000 in transfection medium [high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 2% (vol/vol) FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine]. After 24 h, the medium was changed to fresh transfection medium and grew for another 22 h. BAPTA (20 μM), rapamycin (10 μM), or torin (100 μM) was added 1 h before cell lysis for western. For Ca2+ deprivation, the cells were washed once with HBSS and incubated in fresh HBSS for 1 h. For ionomycin and IGF experiment, cultured cells were plated on 12-well plates at about 40% confluence. After 24 h, the cells were changed to starvation medium (low-glucose DMEM supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine) after PBS washing. After 20 h starvation, ionomycin (0.75 μM) or IGF (10 ng/mL) was added and incubated for 1 h and 10 min, respectively. The HBSS and blockers were treated 10 min before stimulation. For Western blot, cell plates were placed in ice and rinsed once with ice-cold PBS, and then cells were lysed in lysis buffer for 30 min. Lysis buffer consisted of 50 mM Tris⋅HCl at pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate, 0.5% SDS supplemented with EDTA-free cOmplete ULTRA tablets (Roche), and PhosSTOP Complete Easypack (Roche). Lysed cells were transferred and spun at 16,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant of cell lysates were saved and diluted with 4× SDS sample buffer. Equal amounts of protein samples were loaded onto SDS gels, and the Western blotting procedures were performed according to standard protocols. The antibodies against the different markers included: pS6K1, β-actin, α-tubulin (Cell Signaling), and Gq/11 (Santa Cruz).

Electrophysiological Recordings and Analysis.

MEA recordings of retina were performed on mice 4 wk after injection of AAVs. Mice were dark adapted for more than 2 h before dissection. Retinas were carefully dissected from eyecups, and incubated with Ringer’s solution [NaCl 110 mM, CaCl2·2H2O 1 mM, KCl 2.5 mM, MgCl2 1.6 mM, NaHCO3 22 mM, D-glucose 10 mM aerated with 95% (vol/vol) O2/5% CO2] at room temperature. For recording, flat-mounted retinas were placed ganglion cell layer down onto an MEA system (USB-MEA256-System, Multi-Channel Systems). The MEA electrodes were 30 μm in diameter, spaced 100 μm apart, forming a 16 × 16 grid. The retina was then incubated in the dark for >1 h to stabilize its condition and be further dark-adapted. Spontaneous activities were then recorded before light stimuli were presented. All recordings were performed at 32 °C, usually with a perfusion speed of 3∼4 mL/min. The light stimulus was a spot (diameter = 256 μm) flashing black and white (near 100% contrast) at a frequency of 1/3 Hz, with On and Off periods lasting 1.5 s each. Spikes from single units were sorted using a homemade offline sorter written in Igor. For each single unit, spikes from eight repeats were binned into 50-ms bins for the calculation of peri-stimulus time histogram (PSTH). The width of the PSTH above one-third of its peak value is taken as the duration of the response. Total number of spikes 0–1.5 s after light onset (for On cells) or offset (for Off cells) was used to calculate average response firing rate. Total number of spikes 1.35–1.5 s after light onset/offset was used to calculate average spontaneous firing rate during moderate light stimulus. For On–Off cells, the values for both the On period and the Off period were included.

Statistical Analysis.

Two-tailed Student's t test was used for the single comparison between two groups. The rest of the data were analyzed using ANOVA. Post hoc comparisons were carried out when a main effect showed statistical significance. All analysis was conducted by GraphPad Prism. All data were presented as mean ± SEM.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the Hong Kong Research Grants Council Theme-based Research Scheme (T13-607/12R), the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (AoE/M-09/12, 662012, 689913, 16101414), and the Hong Kong Spinal Cord Injury Fund.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1523645113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Schwab ME, Bartholdi D. Degeneration and regeneration of axons in the lesioned spinal cord. Physiol Rev. 1996;76(2):319–370. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg JL, Klassen MP, Hua Y, Barres BA. Amacrine-signaled loss of intrinsic axon growth ability by retinal ganglion cells. Science. 2002;296(5574):1860–1864. doi: 10.1126/science.1068428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harel NY, Strittmatter SM. Can regenerating axons recapitulate developmental guidance during recovery from spinal cord injury? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(8):603–616. doi: 10.1038/nrn1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giger RJ, Hollis ER, 2nd, Tuszynski MH. Guidance molecules in axon regeneration. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(7):a001867. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu K, Tedeschi A, Park KK, He Z. Neuronal intrinsic mechanisms of axon regeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:131–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradke F, Fawcett JW, Spira ME. Assembly of a new growth cone after axotomy: The precursor to axon regeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(3):183–193. doi: 10.1038/nrn3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.So KF, Aguayo AJ. Lengthy regrowth of cut axons from ganglion cells after peripheral nerve transplantation into the retina of adult rats. Brain Res. 1985;328(2):349–354. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duan X, et al. Subtype-specific regeneration of retinal ganglion cells following axotomy: Effects of osteopontin and mTOR signaling. Neuron. 2015;85(6):1244–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park KK, et al. Promoting axon regeneration in the adult CNS by modulation of the PTEN/mTOR pathway. Science. 2008;322(5903):963–966. doi: 10.1126/science.1161566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morquette B, et al. REDD2-mediated inhibition of mTOR promotes dendrite retraction induced by axonal injury. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22(4):612–625. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pérez de Sevilla Müller L, Sargoy A, Rodriguez AR, Brecha NC. Melanopsin ganglion cells are the most resistant retinal ganglion cell type to axonal injury in the rat retina. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e93274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt TM, Taniguchi K, Kofuji P. Intrinsic and extrinsic light responses in melanopsin-expressing ganglion cells during mouse development. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100(1):371–384. doi: 10.1152/jn.00062.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ecker JL, et al. Melanopsin-expressing retinal ganglion-cell photoreceptors: Cellular diversity and role in pattern vision. Neuron. 2010;67(1):49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin B, Koizumi A, Tanaka N, Panda S, Masland RH. Restoration of visual function in retinal degeneration mice by ectopic expression of melanopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(41):16009–16014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806114105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Risson V, et al. Muscle inactivation of mTOR causes metabolic and dystrophin defects leading to severe myopathy. J Cell Biol. 2009;187(6):859–874. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sengupta S, Peterson TR, Laplante M, Oh S, Sabatini DM. mTORC1 controls fasting-induced ketogenesis and its modulation by ageing. Nature. 2010;468(7327):1100–1104. doi: 10.1038/nature09584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun F, et al. Sustained axon regeneration induced by co-deletion of PTEN and SOCS3. Nature. 2011;480(7377):372–375. doi: 10.1038/nature10594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Donovan KJ, et al. B-RAF kinase drives developmental axon growth and promotes axon regeneration in the injured mature CNS. J Exp Med. 2014;211(5):801–814. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hattar S, Liao HW, Takao M, Berson DM, Yau KW. Melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells: Architecture, projections, and intrinsic photosensitivity. Science. 2002;295(5557):1065–1070. doi: 10.1126/science.1069609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Do MT, Yau KW. Intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(4):1547–1581. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farrell MS, Roth BL. Pharmacosynthetics: Reimagining the pharmacogenetic approach. Brain Res. 2013;1511:6–20. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z, et al. Orexin/hypocretin activates mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) via an Erk/Akt-independent and calcium-stimulated lysosome v-ATPase pathway. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(46):31950–31959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.600015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knight ZA, et al. Molecular profiling of activated neurons by phosphorylated ribosome capture. Cell. 2012;151(5):1126–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burrone J, O’Byrne M, Murthy VN. Multiple forms of synaptic plasticity triggered by selective suppression of activity in individual neurons. Nature. 2002;420(6914):414–418. doi: 10.1038/nature01242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palczewski K, Orban T. From atomic structures to neuronal functions of g protein-coupled receptors. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2013;36:139–164. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062012-170313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pastuhov SI, et al. Endocannabinoid-Goα signalling inhibits axon regeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans by antagonizing Gqα-PKC-JNK signalling. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1136. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plazas PV, Nicol X, Spitzer NC. Activity-dependent competition regulates motor neuron axon pathfinding via PlexinA3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(4):1524–1529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213048110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldberg JL, et al. Retinal ganglion cells do not extend axons by default: Promotion by neurotrophic signaling and electrical activity. Neuron. 2002;33(5):689–702. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00602-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldberg JL. Role of electrical activity in promoting neural repair. Neurosci Lett. 2012;519(2):134–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson GA, Madison RD. Axotomized mouse retinal ganglion cells containing melanopsin show enhanced survival, but not enhanced axon regrowth into a peripheral nerve graft. Vision Res. 2004;44(23):2667–2674. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joo HR, Peterson BB, Dacey DM, Hattar S, Chen SK. Recurrent axon collaterals of intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. Vis Neurosci. 2013;30(4):175–182. doi: 10.1017/S0952523813000199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorenzana AO, Lee JK, Mui M, Chang A, Zheng B. A surviving intact branch stabilizes remaining axon architecture after injury as revealed by in vivo imaging in the mouse spinal cord. Neuron. 2015;86(4):947–954. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu K, et al. PTEN deletion enhances the regenerative ability of adult corticospinal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(9):1075–1081. doi: 10.1038/nn.2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zukor K, et al. Short hairpin RNA against PTEN enhances regenerative growth of corticospinal tract axons after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2013;33(39):15350–15361. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2510-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]