Significance

We identified transgenic plants that are extremely resistant to drought from a large-scale screening of transgenic plants overexpressing the pyrabactin resistance 1-like (PYL) family of abscisic acid (ABA) receptors. We explored how these plants resist drought by examining both short-term responses, such as stomatal closure, and long-term responses, such as senescence. The physiological roles of ABA-induced senescence under stress conditions and the underlying molecular mechanism are unclear. Here, we found that ABA induces senescence by activating ABA-responsive element-binding factors and Related to ABA-Insensitive 3/VP1 transcription factors through core ABA signaling. Our results suggest that PYL9 promotes drought resistance by not only limiting transpirational water loss but also, causing summer dormancy-like responses, such as senescence, in old leaves and growth inhibition in young tissues under severe drought conditions.

Keywords: drought stress, abscisic acid, PYL, dormancy, Arabidopsis

Abstract

Drought stress is an important environmental factor limiting plant productivity. In this study, we screened drought-resistant transgenic plants from 65 promoter-pyrabactin resistance 1-like (PYL) abscisic acid (ABA) receptor gene combinations and discovered that pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic lines showed dramatically increased drought resistance and drought-induced leaf senescence in both Arabidopsis and rice. Previous studies suggested that ABA promotes senescence by causing ethylene production. However, we found that ABA promotes leaf senescence in an ethylene-independent manner by activating sucrose nonfermenting 1-related protein kinase 2s (SnRK2s), which subsequently phosphorylate ABA-responsive element-binding factors (ABFs) and Related to ABA-Insensitive 3/VP1 (RAV1) transcription factors. The phosphorylated ABFs and RAV1 up-regulate the expression of senescence-associated genes, partly by up-regulating the expression of Oresara 1. The pyl9 and ABA-insensitive 1-1 single mutants, pyl8-1pyl9 double mutant, and snrk2.2/3/6 triple mutant showed reduced ABA-induced leaf senescence relative to the WT, whereas pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic plants showed enhanced ABA-induced leaf senescence. We found that leaf senescence may benefit drought resistance by helping to generate an osmotic potential gradient, which is increased in pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic plants and causes water to preferentially flow to developing tissues. Our results uncover the molecular mechanism of ABA-induced leaf senescence and suggest an important role of PYL9 and leaf senescence in promoting resistance to extreme drought stress.

Cell and organ senescence causes programmed cell death to regulate the growth and development of organisms. In plants, leaf senescence increases the transfer of nutrients to developing and storage tissues. Recently, studies on transgenic tobacco showed that delayed leaf senescence increases plant resistance to drought stress (1). However, the senescence and abscission of older leaves and subsequent transfer of nutrients are known to increase plant survival under abiotic stresses, including drought, low or high temperatures, and darkness (2, 3). Senescence mainly develops in an age-dependent manner and is also triggered by environmental stresses and phytohormones, such as abscisic acid (ABA), ethylene, salicylic acid, and jasmonic acid, but delayed by cytokinin (4).

Senescence-associated genes (SAGs) are induced by leaf senescence. The expression of SAGs is tightly controlled by several senescence-promoting, plant-specific NAC (NAM, ATAF1, and CUC2) transcription factors, such as Oresara 1 (ORE1) (5), Oresara 1 sister 1 (ORS1) (6), and AtNAP (7). Environmental stimuli and phytohormones may regulate leaf senescence through NACs. Phytochrome-interacting factor 4 (PIF4) and PIF5 transcription factors promote dark-induced senescence by activating ORE1 expression (8). The expression of ORE1, AtNAP, and OsNAP (ortholog of AtNAP) is up-regulated by ABA by an unknown molecular mechanism (7, 9).

ABA is an important hormone that regulates plant growth and development and responses to abiotic stresses, such as drought and high salinity (10). Although it is well-known that ABA promotes leaf senescence, the underlying molecular mechanism is obscure. Previous studies suggested that ABA promotes senescence by causing ethylene biosynthesis (11). ABA induces expression of several SAGs and yellowing of the leaves, which are typical phenomena associated with leaf senescence (9, 12). ABA is sensed by the pyrabactin resistance 1 and pyrabactin resistance 1-like (PYL)/regulatory component of abscisic acid receptor proteins (13, 14). The ABA-bound PYLs prevent clade A protein phosphatase type 2Cs (PP2Cs) from inhibiting the sucrose nonfermenting 1-related protein kinase 2s (SnRK2s). ABA-activated SnRK2s phosphorylate transcription factors, such as ABA-responsive element-binding factors (ABFs), and these phosphorylated ABFs regulate the expression of ABA-responsive genes (15). In Arabidopsis, 14 PYLs function diversely and redundantly in ABA and drought-stress signaling (16–19). Understanding how each PYL affects drought resistance would have both basic and applied importance. Because constitutive overexpression of stress tolerance genes might inhibit plant growth, the use of stress-inducible or organ-specific promoters should be advantageous.

In this study, we evaluated the drought resistance of 14 transgenic Arabidopsis-overexpressing PYLs driven by the constitutive 35S cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) promoter, the stress-inducible RD29A promoter, the guard cell-specific GC1 and ROP11 promoters (20, 21), and the green tissue-specific ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase small subunit (RBCS) RBCS-1A promoter (22). We found that, relative to the WT and all other combinations, pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic Arabidopsis plants had both greater drought resistance and accelerated drought- or ABA-induced leaf senescence. We discovered that ABA induces leaf senescence in an ethylene-independent manner and that PYL9 promotes ABA-induced leaf senescence by inhibiting PP2Cs and activating SnRK2s. ABA-activated SnRK2s then mediate leaf senescence by phosphorylation of Related to ABA-Insensitive 3/VP1 (RAV1) and ABF2 transcription factors, which then up-regulate the expression of ORE1 and other NAC transcription factors, thereby activating expression of SAGs. Previous research has suggested that transgenic plants with delayed leaf senescence are more resistant to drought stress (1). However, we examined the importance of ABA-induced leaf senescence under drought stress and found that the increased leaf senescence in pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic plants apparently helps generate a greater osmotic potential gradient, which causes water to preferentially flow to developing tissues. Therefore, hypersensitivity to ABA leads to increased senescence and death of old leaves but survival of young tissues during severely limited water conditions through promoting summer dormancy-like responses (23).

Results

Screening Transgenic Arabidopsis for Drought-Stress Survival.

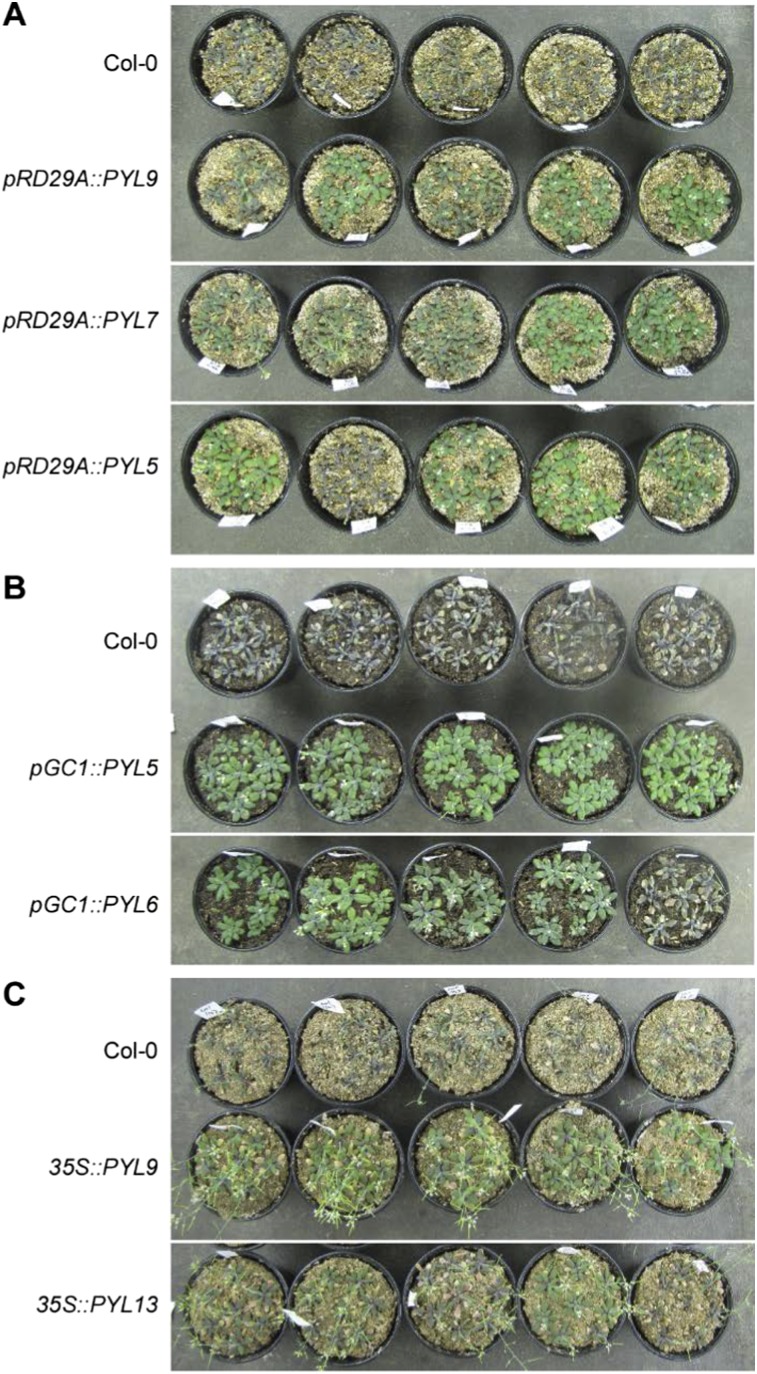

In Arabidopsis, the expression of many PYLs is down-regulated by osmotic stress, which may constitute a negative feedback loop that reduces drought responses (24). In principle, expression modifications that allow general, tissue-specific, or stress-inducible overexpression of PYLs should amplify ABA signaling and increase drought resistance in transgenic plants. Based on this assumption, the following five promoters were used for PYL overexpression: the 35S CaMV promoter, the stress-inducible RD29A promoter, and the tissue-specific promoters GC1, ROP11, and RBCS-1A. Transgenic plants from a total of 65 different promoter-PYL combinations were generated and evaluated for drought-stress resistance (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1). The results indicated that drought resistance was increased by PYLs driven by 35S, pRD29A, and pGC1 promoters but not by the pRBCS-1A promoter. The pGC1-driven lines performed better than the lines driven by the other guard cell-specific promoter, pROP11. Among the combinations, survival was highest for 35S::PYL3/9/13, pRD29A::PYL7/9, and pGC1::PYL3/5/6/7/11 lines. These top drought-resistant lines preferentially cluster on the monomeric PYLs, especially PYL7 and PYL9, which have very high affinities to ABA (16).

Fig. 1.

Screening PYL transgenic lines for resistance to drought stress in Arabidopsis. (A) Drought-resistance screening of PYL transgenic Arabidopsis. Fourteen Arabidopsis PYLs and five promoters were used to generate 65 transgenic plants with different promoter-PYL combinations. Two-week-old plants were subjected to drought stress by withholding water for 20 d. Survival rates were calculated at 2 d after rehydration. –, No transgenic plants were obtained. (B and C) pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic plants exhibit improved drought-stress resistance with ABA treatment. Plants were subjected to drought stress after flowering. After water was withheld for 12 d, plants were treated once with 10 µM ABA. (B) Images of representative seedlings. (C) Soil water content during the drought-stress period. Error bars indicate SEM (n ≥ 4).

Fig. S1.

Drought resistance screening of PYL transgenic Arabidopsis. Two-week-old plants were subjected to drought stress by withholding water for 20 d, by which time most Col-0 WT plants had died. Images of representative plants after 20 d of drought treatment. pRD29A::PYL transgenic lines (A), pGC::PYL transgenic lines (B), and 35S::PYL transgenic lines (C) are shown.

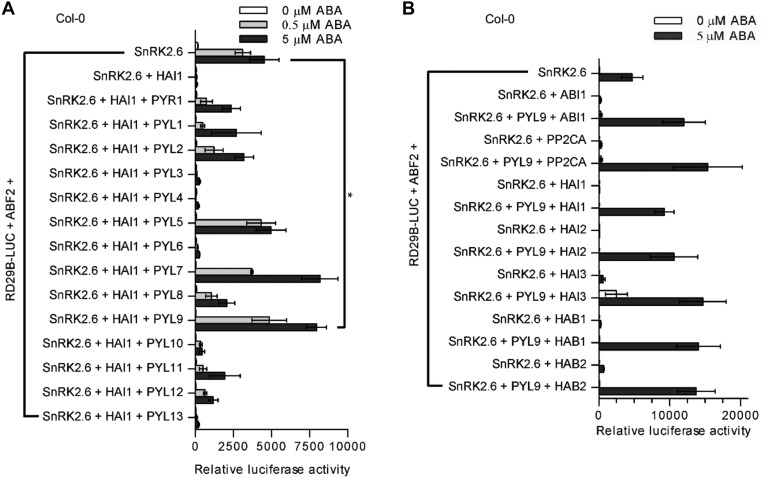

We also evaluated the PYLs in a transient expression assay in Arabidopsis protoplasts (25). Highly ABA-induced 1 (HAI1), HAI2, and HAI3 PP2Cs interact with only a few of these PYLs, even in the presence of 10 µM ABA (24). Transfections of HAI1 inhibited RD29B-LUC expression. PYL3, PYL4, PYL6, or PYL13 did not inhibit HAI1, whereas cotransfections of HAI1 with PYL5, PYL7, or PYL9 strongly enabled the ABA-dependent induction of RD29B-LUC expression (Fig. S2A). Furthermore, cotransfections of PYL9 together with each of the PP2Cs strongly enabled the ABA-dependent induction of RD29B-LUC (Fig. S2B). Similar to the ABA-independent inhibition of ABA-insensitive 1 (ABI1) by PYL10 (16, 25), PYL9 can partially inhibit HAI3 activity in the absence of exogenous ABA. These results suggested that PYL9 strongly inhibits the phosphatase activities of clade A PP2Cs in plant cells, an inhibition that activates the core ABA signaling pathway and is presumably involved in the drought resistance of pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic plants.

Fig. S2.

PYL9 inhibits all tested PP2Cs in protoplasts. (A) PYL5, PYL7, and PYL9 can antagonize the ability of HAI1 to inhibit the induction of RD29B-LUC expression in the presence of 0.5 µM ABA in Col-0 protoplasts. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test). (B) PYL9 can reduce the ability of all tested PP2Cs to inhibit the ABA-dependent induction of RD29B-LUC expression in protoplasts. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3).

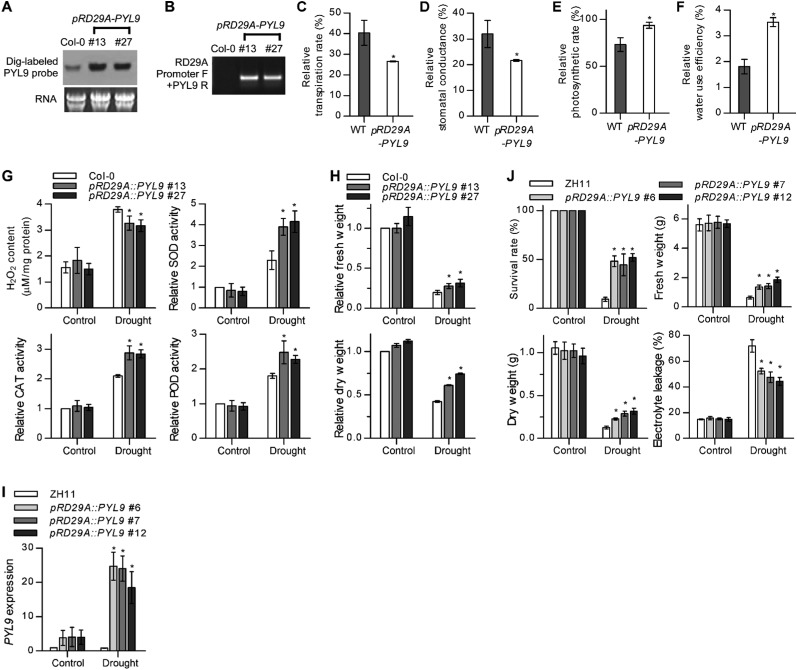

PYL9 transcripts were significantly more abundant in pRD29A::PYL9 lines than in the WT under drought stress (Fig. S3A). Application of ABA after water was withheld for 12 d significantly increased the drought resistance of the pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic plants after flowering (Fig. 1 B and C). The delayed wilting and drying in pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic plants was correlated with a reduction in water loss from the soil, indicating a reduction in transpiration. This result revealed that PYL9, when driven by the pRD29A promoter, is useful for generating transgenic plants that are extremely resistant to drought when treated with ABA or ABA-mimicking compounds (26, 27). We chose the pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic lines for additional study (Fig. S3B).

Fig. S3.

Stress-inducible overexpression of PYL9 improves drought-stress resistance. (A) Northern blot verification using DIG-labeled PYL probes. Samples were collected under drought-stress conditions. DIG, digoxigenin. (B) PCR verification using promoter forward primer plus gene-specific reverse primer. (C–F) Physiological parameters of pRD29A::PYL9 lines under drought-stress conditions. Three-week-old plants were subjected to drought stress (water was withheld for 5 d) before parameters were measured. pRD29A::PYL9 values are the means of three independent transgenic lines. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). (G) H2O2 content and the antioxidant enzyme activities of the WT (Col-0) and pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic Arabidopsis under drought-stress conditions. For H2O2 content measurement, water was withheld from 2-wk-old plants for 14 d, and the leaves were collected. For antioxidant enzyme activities, water was withheld from 3-wk-old plants for 10 d. Values for enzyme activities were normalized to those for the WT plants grown under well-watered conditions, which were set at one. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). (H) Relative fresh and dry weights of the WT (Col-0) and pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic Arabidopsis. Water was withheld from 2-wk-old plants for 20 d, and the aboveground materials were collected and weighed before and after drying. The values were normalized to those for the WT plants grown under well-watered conditions, which were set at one. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). (I) Expression of the Arabidopsis PYL9 transgene in rice. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3). (J) Survival rate, total biomass, and electrolyte leakage of the WT (ZH11) and pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic rice. Plants were collected 14 d after water was withheld. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test).

pRD29A::PYL9 Confers Drought Resistance to Both Arabidopsis and Rice.

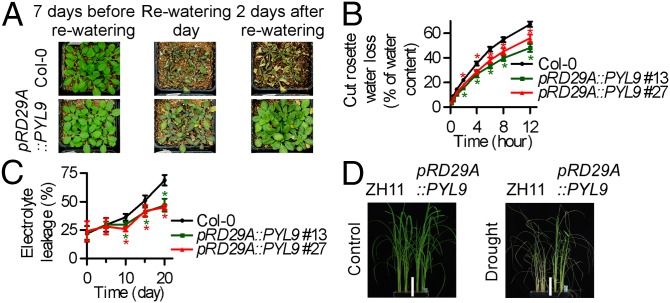

The Arabidopsis pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic lines also exhibited increased drought resistance before flowering under short-day conditions (Fig. 2A). The greater drought-stress survival of pRD29A::PYL9 lines was associated with reduced water loss (Fig. 2B), reduced cell membrane damage (Fig. 2C), reduced transpiration rate and stomatal conductance (Fig. S3 C and D), enhanced photosynthetic rate and water use efficiency (Fig. S3 E and F), reduced accumulation of toxic hydrogen peroxide, and enhanced activities of antioxidant enzymes (Fig. S3G). As a result, the total biomass was greater in pRD29A::PYL9 lines than in the WT after drought treatment but did not differ statistically from the WT in the absence of drought treatment (Fig. S3H). These results showed that the pRD29A::PYL9 transgene confers drought resistance to Arabidopsis in at least two ways (i.e., by reducing water loss and by reducing oxidative injury).

Fig. 2.

pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic plants exhibit improved drought-stress resistance in both Arabidopsis and rice. (A) pRD29A::PYL9 confers drought resistance in Arabidopsis. Water was withheld from 3-wk-old Arabidopsis plants for 20 d under short-day conditions before watering was resumed. Representative images show plants 7 d before rewatering, on the day of rewatering, and 2 d after watering was resumed. (B) Cumulative transpirational water loss from rosettes of the WT (Col-0) and pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic Arabidopsis at the indicated times after detachment. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). (C) Electrolyte leakage of the WT (Col-0) and pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic Arabidopsis at the indicated days after water was withheld. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). (D) pRD29A::PYL9 confers drought resistance in rice. Water was withheld from 4-wk-old rice plants for 14 d. Plants were photographed 14 d after watering was resumed. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test).

To determine whether pRD29A::PYL9 may confer drought resistance in crop plants, we generated pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic rice (Oryza sativa L.) in the japonica variety Zhonghua 11 (ZH11), in which PYL9 expression was dramatically induced by drought stress (Fig. S3I). pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic rice exhibited increased drought resistance (Fig. 2D). After a 2-wk drought treatment, nearly 50% of pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic rice growing in soil survived, but only about 10% of the ZH11 WT plants survived (Fig. S3J). Although pRD29A::PYL9 increased survival, total biomass, and cell membrane integrity of transgenic rice under drought conditions, the transgene did not adversely affect plant growth and development under well-watered conditions (Fig. S3 H and J). These results showed that pRD29A::PYL9 increases drought resistance in rice without retarding growth under well-watered conditions.

PYL9 Promotes ABA-Induced Leaf Senescence in Both Arabidopsis and Rice.

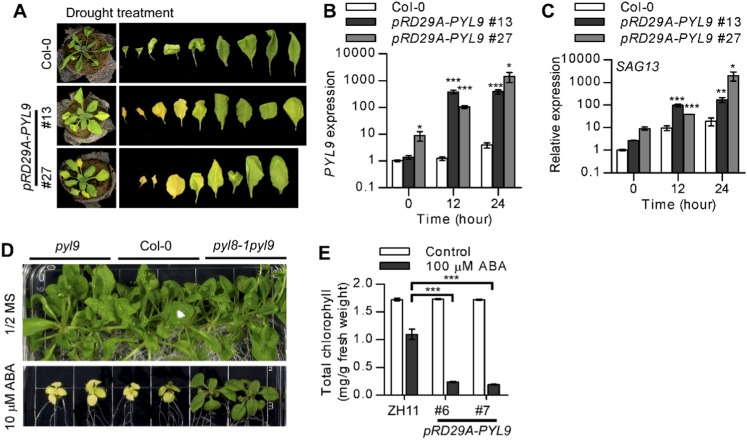

After the drought treatment in our experiments, it was evident that older leaves of pRD29A::PYL9 lines became yellow, sooner than in the Columbia-0 (Col-0) WT (Fig. 2A and Fig. S4A). ABA-induced leaf yellowing was also accelerated in pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic plants (Fig. 3A). Consistent with its visible phenotypes, pRD29A::PYL9 lines had a lower chlorophyll level than the Col-0 WT after treatment with 20 µM ABA (Fig. 3B). SAGs are molecular markers of senescence and especially, ABA-induced senescence (12). Consistent with the elevated PYL9 expression (Fig. S4B), both SAG12 and SAG13 were more strongly induced after ABA treatment in mature leaves of pRD29A::PYL9 lines than in those of the WT (Fig. 3C and Fig. S4C). This result showed that pRD29A::PYL9 accelerates ABA-induced leaf senescence of older leaves in Arabidopsis.

Fig. S4.

PYL9 promotes drought- and ABA-induced leaf yellowing in Arabidopsis. (A) pRD29A::PYL9 accelerates drought-induced leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Water was withheld from 3-wk-old Arabidopsis plants growing in Jiffy 7 Peat Soil for 14 d. (B) Expression of PYL9 in pRD29A::PYL9 lines. Quantitative RT-PCR was conducted with leaves of 4-wk-old Arabidopsis plants that were grown in soil and sprayed with 20 µM ABA for 12 and 24 h. The expression level of PYL9 in Col-0 without ABA treatment was set at one. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3). (C) Expression of SAG13 in pRD29A::PYL9 lines. The expression level of SAG13 in Col-0 without ABA treatment was set at one. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3). (D) Leaves of WT (Col-0), pyl9 mutant, and pyl8-1pyl9 double mutant at 17 d after transfer to Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium with or without 10 µM ABA under normal light (80–100 µmol m−2 s−1). (E) Chlorophyll content in third oldest leaves of WT (ZH11) and pRD29A::PYL9 rice lines that were growing in soil after they were sprayed with 100 µM ABA. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test); **P < 0.01 (Student’s t test); ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t test).

Fig. 3.

PYL9 promotes ABA-induced leaf senescence in both Arabidopsis and rice. (A and B) pRD29A::PYL9 accelerates ABA-induced leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. (A) Plants were photographed 2 d after they were sprayed with ABA. (B) Chlorophyll content in mature leaves of WT (Col-0) and pRD29A::PYL9 lines. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3). (C) Expression of SAG12 in pRD29A::PYL9 lines. The expression level of SAG12 in Col-0 without ABA treatment was set at one. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3). (D and E) Leaf growth and chlorophyll content of the WT (Col-0), the pyl9 mutant, and the pyl8-1pyl9 double mutant were documented at 17 d after the seedling were transferred to Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium with or without 10 µM ABA and grown under low light (30–45 µmol m−2 s−1). Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3). (F) pRD29A::PYL9 accelerates ABA-induced leaf senescence in rice. The third-oldest leaves of WT (ZH11) and pRD29A::PYL9 rice lines were photographed. (G) Expression of Osh36 and Osl85 in pRD29A::PYL9 rice lines. The expression level of SAGs in ZH11 without ABA treatment was set at one. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test); **P < 0.01 (Student’s t test); ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t test).

Enhanced drought survival and senescence are both associated with ABA signaling. To verify that PYL9 mediated these responses by making the plants hypersensitive to ABA, we analyzed the leaf yellowing of the pyl9 transferred DNA (T-DNA) insertion mutant after ABA treatment of plate-grown seedlings. ABA-induced leaf yellowing was lower in the pyl9 mutant than in the WT under low light (30–45 µmol m−2 s−1) (Fig. 3 D and E) but not under normal light (80–100 µmol m−2 s−1) (Fig. S4D) because of genetic redundancy. Moreover, the pyl8-1pyl9 double mutant was less sensitive than the pyl9 mutant to ABA-induced leaf yellowing, indicating that PYL9 and PYL8 function together in ABA-induced leaf senescence. Furthermore, PYL9 is highly expressed in senescent leaves and stamens according to the Arabidopsis electronic fluorescent pictograph (eFP) browser, which is consistent with the expression of SAG12 (Fig. S5). These results confirm that PYL9 functions in both ABA-induced drought survival and senescence by hypersensitizing Arabidopsis to ABA.

Fig. S5.

PYL9 and SAG12 expression in Arabidopsis according to the Arabidopsis electronic fluorescent pictograph (eFP) browser (bar.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi).

ABA-induced leaf yellowing was also accelerated in pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic rice (Fig. 3F and Fig. S4E). After ABA treatment, severe yellowing was evident in the third oldest leaves of the pRD29A::PYL9 lines but not those of the ZH11 WT. Moreover, two SAGs, Osh36 and Osl85 (9), were more strongly induced after ABA treatment in the third-oldest leaves of pRD29A::PYL9 rice lines than in those of the ZH11 WT (Fig. 3G). These results show that PYL9 also mediates ABA-induced leaf senescence in rice.

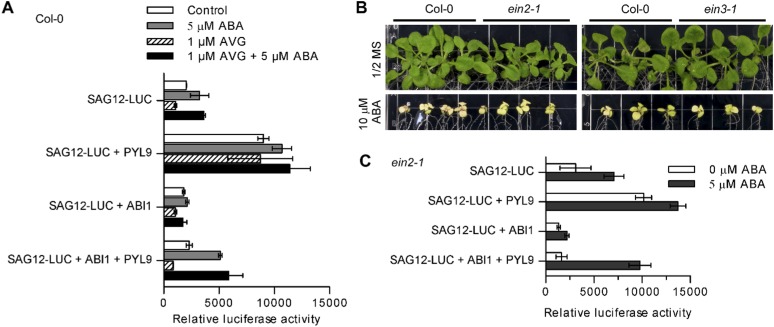

ABA Induces Leaf Senescence Through the Core ABA Signaling Pathway.

To investigate whether ABA induction of senescence requires ethylene, we treated protoplasts with the ethylene biosynthesis inhibitor aminoethoxyvinylglycine (AVG). We found that AVG treatment decreased SAG12-LUC expression in the absence of ABA (Fig. S6A), consistent with the known role of ethylene in promoting senescence. However, AVG treatment did not inhibit either ABA-induced or PYL9-enhanced SAG12-LUC expression (Fig. S6A). We found that ABA-induced leaf yellowing was not reduced in the ethylene-resistant mutants ein2-1 and ein3-1 (Fig. S6B). Furthermore, ABA-induced and PYL9-enhanced SAG12-LUC expression was not blocked in ein2-1 mutant protoplasts (Fig. S6C). These results suggest that the induction of senescence by ABA is not mediated through ethylene.

Fig. S6.

ABA-induced senescence is not mediated through its promotion of ethylene production. (A) SAG12-LUC expression in Col-0 WT protoplasts treated with the ethylene biosynthesis inhibitor AVG. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3). (B) Leaf growth of WT (Col-0) and ethylene-insensitive mutants ein2-1 and ein3-1 13 d after seedlings were transferred to a medium with or without 10 µM ABA. (C) SAG12-LUC expression in ein2-1 mutant protoplasts cotransformed with ABI1 and PYL9. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3).

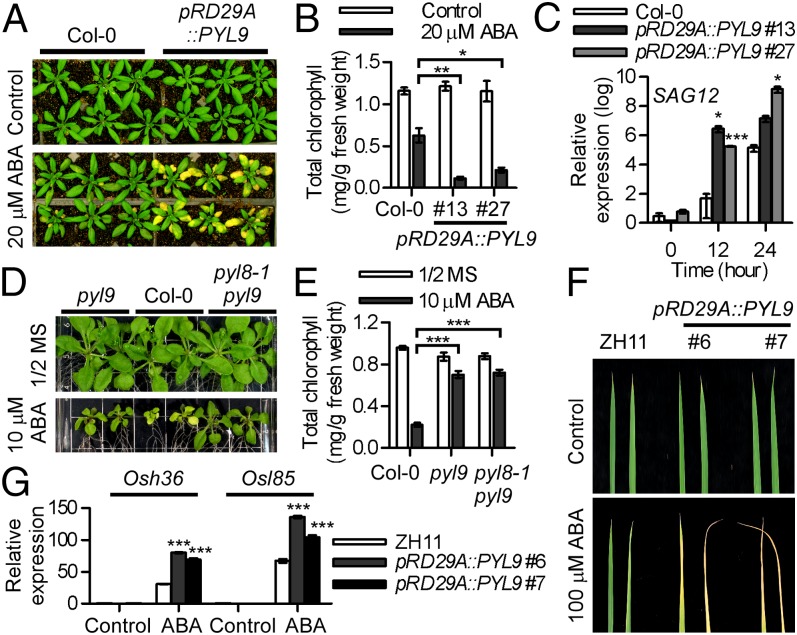

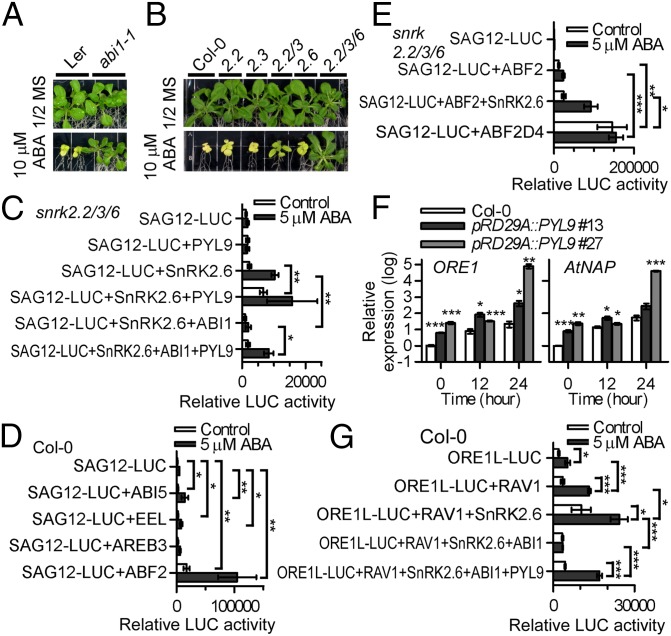

We generated transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing HA- and YFP-tagged PYL9 under the native PYL9 promoter (ProPYL9:PYL9-HA-YFP) (Fig. S7A) and isolated PYL9-associated proteins using tandem affinity purification (Fig. S7B and Dataset S1). The associated proteins mainly included several PP2Cs, such as HAB2, PP2CA, and ABI1, in an ABA- or osmotic stress-enhanced manner (Fig. S7C). PYL9 interacted with all PP2Cs tested in an ABA-independent manner in yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assays (Fig. S7D). We fused the 788-bp fragment of the SAG12 promoter (SAG12-LUC) (Fig. S7E) to the LUC reporter gene and used the construct as a senescence-responsive reporter. The 788-bp SAG12 promoter contains the 9-mer sequence T(TAG)(GA)CGT(GA)(TCA)(TAG), which is the preferred binding site of ORE1 (28). All PP2Cs decreased SAG12-LUC expression in the presence of ABA (Fig. S7 F and G). The inhibition of SAG12-LUC expression by ABI1 can be released by coexpression of PYL9 (Fig. S7F). Moreover, ABA-induced leaf yellowing was weaker in the abi1-1 mutant than in the Landsberg erecta (Ler) WT (Fig. 4A and Fig. S7H). The abi1-1 mutant is ABA-resistant and contains a G180D point mutation. PYLs do not interact with or inhibit ABI1G180D, even in the presence of ABA (13). These results indicated that PP2Cs inhibit ABA-induced senescence.

Fig. S7.

PP2Cs are negative regulators of leaf senescence. (A) Detection of the PYL9-HA-YFP protein in a sample purified from 10-d-old seedlings of ProPYL9:PYL9-HA-YFP–expressing lines. PYL9-HA-YFP protein was detected with anti-GFP mouse antibodies (Roche). (B) Procedure for purification of PYL9-associated proteins using tandem affinity purification (TAP) in extracts of 10-d-old seedlings of the transgenic plants treated with ABA or osmotic stress. (C) Identification of PYL9-associated proteins in TAP-MS analyses using ProPYL9:PYL9-HA-YFP transgenic plants not treated or treated with ABA or mannitol. Detailed data of the peptides identified by MS analyses are provided in Dataset S1. (D) PYL9-PP2C interactions in the Y2H assay. Interaction was determined by yeast growth on media lacking His with and without ABA. Dilutions (10−1, 10−2, and 10−3) of saturated cultures were spotted onto the plates, which were photographed after 5 d. The activating domain (AD)-MYB44/binding domain (BD)-PYL8 and AD/BD-PYL9 combinations were included as positive and negative controls, respectively, for the Y2H interaction assay. (E) Promoter region for SAG12-LUC reporter fusion. The ORE1 binding site [(TAG)(GA)CGT(GA)(TCA)(TAG)] is marked with red. (F) SAG12-LUC expression in Col-0 WT protoplasts cotransformed with ABI1 and PYL9 (n = 4 experiments). Values are means ± SEMs. (G) SAG12-LUC expression in Col-0 WT protoplasts cotransformed with PP2Cs (n = 3 experiments). Values are means ± SEMs. (H and I) Chlorophyll content of the WT (Ler), the abi1-1 mutant, WT (Col-0), and snrk2.2/3/6 triple mutant 13 d after seedlings were transferred to a medium with or without 10 µM ABA. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 6). *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test); **P < 0.01 (Student’s t test); ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t test). Ler, Landsberg erecta; MS, Murashige and Skoog medium; NOS, NOS terminator; WB, Western blotting; Y2H, yeast two hybrid.

Fig. 4.

Core ABA signaling promotes ABA-induced leaf senescence. (A and B) Leaf growth of the WT [Landsberg erecta (Ler)]; the abi1-1 mutant; the WT (Col-0); snrk2.2, snrk2.3, and snrk2.6 single mutants; snrk2.2/3 double mutant; and snrk2.2/3/6 triple mutant at 13 d after seedlings were transferred to Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium with or without 10 µM ABA. (C) SAG12-LUC expression in snrk2.2/3/6 triple-mutant protoplasts cotransformed with SnRK2.6, ABI1, and PYL9. Error bars indicate SEM (n ≥ 3). (D) SAG12-LUC expression in Col-0 protoplasts cotransformed with ABI5, EEL, AREB3, and ABF2. Error bars indicate SEM (n ≥ 3). (E) SAG12-LUC expression in snrk2.2/3/6 triple-mutant protoplasts cotransformed with SnRK2.6, ABF2, and ABF2S26DS86DS94DT135D. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 4). (F) Expression of ORE1 and AtNAP in pRD29A::PYL9 lines. The expression level of ORE1 and AtNAP in Col-0 without ABA treatment was set at one. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3). (G) ORE1L-LUC expression in Col-0 protoplasts cotransformed with RAV1, SnRK2.6, ABI1, and PYL9. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test); **P < 0.01 (Student’s t test); ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t test).

We hypothesized that PYL9 may promote leaf senescence by activating SnRK2s. The snrk2.2/3/6 triple mutant was insensitive to ABA-induced leaf yellowing (Fig. 4B and Fig. S7I). Moreover, SAG12-LUC expression was not enhanced by ABA treatment in snrk2.2/3/6 triple-mutant protoplasts, but ABA induction of SAG12-LUC expression in such protoplasts could be recovered by transfection of SnRK2.6 (Fig. 4C), suggesting that ABA-induced SAG12 expression depends on the SnRK2s. The activation of SAG12-LUC expression by PYL9 was abolished in snrk2.2/3/6 triple-mutant protoplasts, but such expression was also recovered with transfection of SnRK2.6. The activation of SAG12-LUC expression by SnRK2.6 was blocked by transfection of ABI1, which can be released by PYL9. These results suggest that PYL9 promotes ABA-induced leaf yellowing and SAG12 expression through core ABA signaling.

Phosphorylation of ABFs by SnRK2s Facilitates ABA-Induced SAG12 Promoter Activity in Leaf Protoplasts.

ABA-activated SnRK2s phosphorylate ABF transcription factors, which activate these factors and enable them to regulate expression of ABA-responsive genes (15). To identify the transcription factors involved in ABA-induced leaf senescence, we cloned several ABFs, including ABF2, ABI5, enhanced EM level (EEL), and AREB3, and coexpressed them with SAG12-LUC in Col-0 leaf protoplasts (Fig. 4D and Fig. S8A). We found that SAG12-LUC expression in protoplasts was dramatically increased by ABF2, was less dramatically but significantly increased by ABI5 and EEL, and was not increased by AREB3 (Fig. 4D). The phosphorylation of ABF2 at amino acid residues S26, S86, S94, and T135 is important for stress-responsive gene expression in Arabidopsis, and these sites are putatively phosphorylated by SnRK2s (15, 25). Expression of SnRK2.6 significantly enhanced the ability of ABF2 to increase SAG12-LUC expression in the presence of ABA. Furthermore, ABF2S26DS86DS94DT135D constitutively increased SAG12-LUC expression in the snrk2.2/3/6 triple-mutant protoplasts (Fig. 4E). These results suggested that phosphorylation of ABFs by SnRK2s promotes activity of the ABA-induced leaf senescence pathway.

Fig. S8.

ABA-induced expression of senescence-related NACs. (A) Phylogenetic tree of ABFs in Arabidopsis. (B) SAG12-LUC expression in Col-0 protoplasts cotransformed with ORE1, ORS1, and AtNAP. Error bars indicate SEM (n ≥ 3). *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test); **P < 0.01 (Student’s t test); ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t test). (C) Diagram of promoters of ORE1, ORS1, and AtNAP. (D) Expression of ORE1, ORS1, and AtNAP with ABA treatment according to data from the Arabidopsis eFP browser (bar.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi). (E) Scheme for the ORE1L-LUC reporter. We fused the 3,984-bp fragment of the ORE1 promoter to the LUC reporter gene (ORE1L-LUC) to use as a senescence-responsive reporter. The 3,984-bp ORE1 promoter contains the RAV1(1) [gCaACA(g/t)(a/t)] and RAV1(2) [caCCTG(a/g)] motifs. bZIP, the basic region-leucine zipper; eFP, electronic fluorescent pictograph.

Leaf senescence is promoted by several NAC transcription factors, such as ORE1 (5), ORS1 (6), and AtNAP (7). ABA-induced leaf senescence was reported to be delayed in ore1 mutant leaves (29). SAG12-LUC expression was clearly increased by ORE1 and AtNAP and slightly increased by ORS1 (Fig. S8B). The ORE1 and AtNAP promoter regions contain several abscisic acid-responsive element (ABRE) motifs and RAV1 binding sites (Fig. S8C). ABRE motifs are the binding sites for the ABF transcription factors, which our results suggested to be positive regulators of senescence (Fig. 4 D and E). ABA-activated SnRK2s phosphorylate RAV1 (30), which positively regulates leaf senescence in Arabidopsis (31). According to the Arabidopsis eFP browser, expression of ORE1, ORS1, and AtNAP is enhanced by ABA (Fig. S8D). ABA treatment, indeed, induced the expression of ORE1 and AtNAP in mature leaves, and the expression levels were higher in pRD29A::PYL9 lines compared with those of the WT (Fig. 4F). We fused a 3,984-bp fragment of the ORE1 promoter to the LUC reporter gene (ORE1L-LUC) (Fig. S8E) to use as a senescence-responsive reporter. According to the AthaMap, the 3,984-bp ORE1 promoter contains multiple RAV1(1) [gCaACA(g/t)(a/t)] and RAV1(2) [caCCTG(a/g)] motifs, which are the preferred binding sites for RAV1. The ORE1L-LUC expression was enhanced by RAV1 and SnRK2.6 and repressed by ABI1 (Fig. 4G). Expression of PYL9 released the inhibition of ABI1 on ORE1-LUC expression in an ABA-dependent manner. These results suggested that ABA core signaling up-regulates expression of SAGs through phosphorylation of both ABFs and RAV1 transcription factors.

Stressed pRD29A::PYL9 Transgenic Plants Display Enhanced Osmotic Potential Gradients Between Senescing Leaves and Buds.

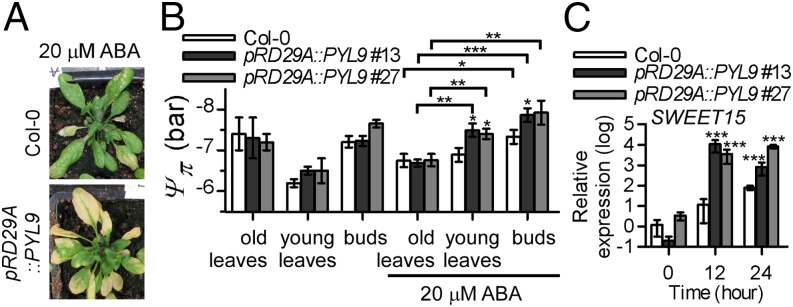

pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic plants are hypersensitive to ABA-induced leaf senescence (Fig. 3). In these plants, leaf yellowing spreads from older to younger leaves (Fig. 5A). Leaf wilting in pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic plants was observed after 3 d of continuous ABA treatment, even in plants that were well-watered (Fig. 5A). This unusual event suggests that water transport to senescing leaves was reduced or blocked. Water moves from areas of high water potential to areas of low water potential, and plants control water potential, in part, by regulating osmotic potential (Ψπ). We found that ABA treatment reduced the osmotic potential in the developing bud tissue but not in the old leaves (Fig. 5B). The osmotic potential was lower in developing tissues of pRD29A::PYL9 lines than in the WT but did not differ in old leaves of the transgenic plants vs. the WT. Thus, the osmotic potential gradient was greater in pRD29A::PYL9 lines than in the WT. As noted above, this gradient would cause water to move preferentially to developing tissues but not to senescing leaves, especially in pRD29A::PYL9 lines. Senescence, which is associated with the remobilization of carbohydrate and nitrogen from the senescing tissue to the developing or storage tissues, contributes to osmotic potential regulation. Carbohydrate is transported as sucrose to sink tissues through the phloem. The key step for phloem loading is sucrose efflux, which is mediated by SWEET proteins (32). We determined that SWEET15/SAG29 is induced in senescing Arabidopsis leaves. Induction of SWEET15 expression is greater in mature leaves of pRD29A::PYL9 lines than in those of the WT after ABA treatment (Fig. 5C), suggesting that pRD29A::PYL9 lines have an increased ability to mobilize sucrose from senescing leaves.

Fig. 5.

pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic plants exhibit an increased within-plant osmotic potential gradient. (A and B) pRD29A::PYL9 accelerates ABA-induced drying in senescing leaves under well-watered conditions. Four-week-old Arabidopsis plants growing in soil were sprayed with 20 µM ABA plus 0.2% Tween-20. (A) Plants were photographed 4 d after they were sprayed with ABA. (B) pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic plants exhibit improved osmoregulation in sink tissues. Samples were collected 2 d after ABA was sprayed. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 6). (C) Expression of SWEET15 in pRD29A::PYL9 lines. The expression level of SWEET15 in Col-0 without ABA treatment was set at one. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test); **P < 0.01 (Student’s t test); ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t test).

Core ABA Signaling Promotes Growth Inhibition and the Expression of Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis Genes.

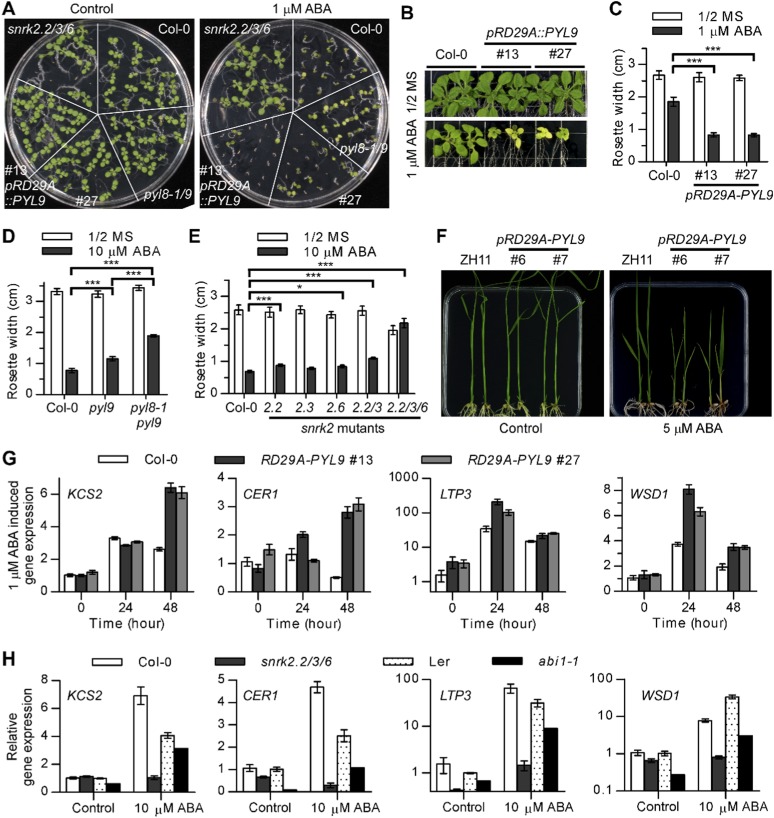

To help plants survive extreme environmental conditions, ABA promotes growth inhibition and dormancy (10). The pRD29A::PYL9 lines showed a stronger seed dormancy and growth inhibition than the Col-0 WT under ABA treatment (Fig. S9 A–C), whereas the seed dormancy and rosette growth of pyl8-1pyl9 and snrk2.2/3/6 were less sensitive to ABA treatment (Fig. S9 A, D, and E). The pRD29A::PYL9 rice lines also showed a more severe growth inhibition than the ZH11 WT in response to the ABA treatment (Fig. S9F). These results indicated that PYL9 promotes, through the core ABA signaling pathway, ABA-induced seed dormancy and growth inhibition of buds.

Fig. S9.

Core ABA signaling promotes ABA-induced growth inhibition and the expression of cuticular wax biosynthesis genes. (A) Seed germination and seedling growth of WT (Col-0), snrk2.2/3/6, pyl8-1pyl9, and pRD29A::PYL9 lines in Murashige and Skoog medium and Murashige and Skoog medium plus 1 µM ABA at 8 d. (B and C) Rosette growth of WT (Col-0) and pRD29A::PYL9 lines at 13 d after transfer to a medium with or without 1 µM ABA. (B) Images of representative seedlings. (C) Rosette width. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 6). (D) Rosette width of WT (Col-0), pyl9, and pyl8-1pyl9 double mutants was documented at 17 d after transfer to a medium with or without 10 µM ABA under low light (30–45 µmol m−2 s−1). Error bars indicate SEM (n = 12). (E) Rosette width of WT (Col-0), single mutants (snrk2.2, snrk2.3, and snrk2.6), snrk2.2/3 double mutant, and snrk2.2/3/6 triple mutant 13 d after transfer to a medium with or without 10 µM ABA. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 8). *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test); ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t test). (F) Seedling growth of WT (ZH11) and pRD29A::PYL9 rice lines 20 d after transfer to a medium with or without 5 µM ABA. (G) Expression of wax biosynthetic genes in pRD29A::PYL9 lines. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed at the indicated time after transfer of 7-d-old seedlings to a medium with or without 1 µM ABA. The expression level of genes in Col-0 without ABA treatment was set at one. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3). (H) Expression of wax biosynthetic genes in snrk2.2/3/6 mutant and abi1-1 mutant. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed at 24 h after transferring 7-d-old seedlings to a medium with or without 10 µM ABA. The expression level of genes in WT (Col-0 and Ler) without ABA treatment was set at one. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3). CER1, ECERIFERUM 1; KCS2, 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthetase 2; Ler, Landsberg erecta; LTP3, lipid transfer protein 3; MS, Murashige and Skoog medium; WSD1, wax ester synthase 1.

ABA promotes stomatal closure to reduce water loss. To protect plants from nonstomatal water loss, ABA induces the accumulation of cuticular wax by up-regulating wax biosynthetic genes (33). The 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthetase 2, ECERIFERUM 1, lipid transfer protein 3, and wax ester synthase 1 were more strongly induced after ABA treatment in pRD29A::PYL9 lines than in the WT (Fig. S9G). Furthermore, the expression of wax biosynthetic genes was reduced in both abi1-1 and snrk2.2/3/6 than in those of the WT in either the absence or presence of ABA (Fig. S9H). These results are consistent with PYL9 promotion of ABA-induced wax biosynthesis through the core ABA signaling pathway. The accumulation of cuticular wax may be especially relevant in very young leaves, where stomata have not developed fully.

Discussion

To escape extreme environmental conditions, plants use a dormancy phase to survive. The two major forms of dormancy are seeds and dormant buds. These forms of dormancy are determined genetically and affected by environmental changes (23). ABA increases plant survival in extreme drought by inducing short-, such as stomatal closure, and long-term responses, such as senescence and abscission, and different forms of dormancy (2, 10, 23). Plants close stomata in response to drought by producing ABA, which is a rapid response that blocks most water loss and gains time for long-term responses to be established. Plants developed an important long-term defense against limited water by favoring water consumption in only newly developed organs and eventually, inducing strong dormancy in meristems or buds. A nonobvious part of this defense in its early stages is the premature senescence and/or abscission of old organs (Fig. S10), which are easily mistaken as drought sensitivity.

Fig. S10.

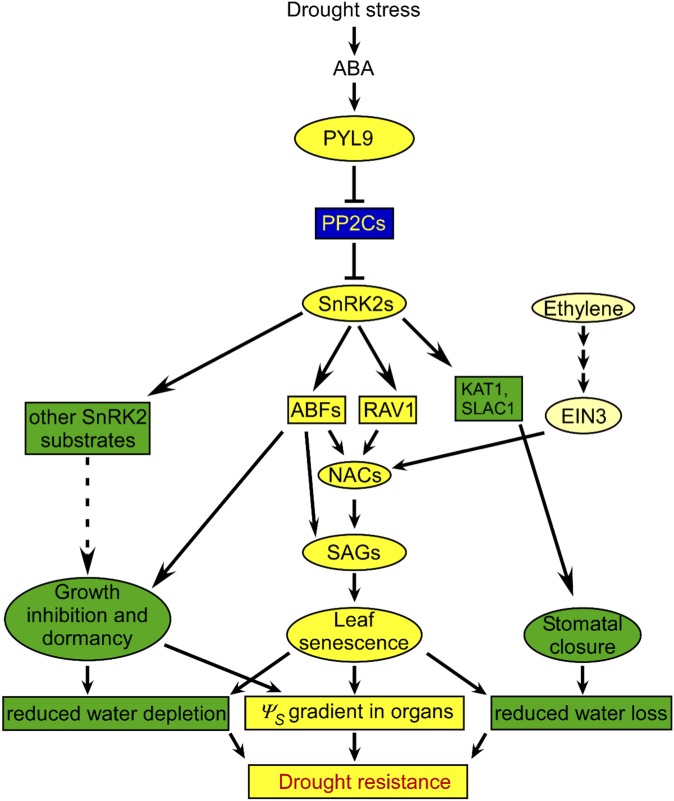

Proposed model of PYL9-enhanced drought resistance in Arabidopsis. Drought stress induces the elevation of ABA concentration. In response to ABA, PYL9 inhibits PP2C activities, resulting in the activation of SnRK2s. Activated SnRK2s promote stomatal closure by phosphorylating KAT1, SLAC1, and SLAH3, which is a rapid response that reduces transpirational water loss. Activated SnRK2s promote leaf senescence by phosphorylating RAV1 and ABFs, which in turn, up-regulates the expression of NAC transcription factors ORE1, ORS1, and AtNAP, elevating the expression of hundreds of SAGs. Other than ABA, ethylene signaling also promotes senescence by up-regulation of NAC expression through EIN3. Leaf senescence promotes carbohydrate and nitrogen remobilization from senescing leaves to sink tissues, which contributes to osmotic potential (Ψπ) reduction in sink tissues and the loss of the ability for osmotic adjustment in senescing leaves. Activated SnRK2s also promote growth inhibition and dormancy by phosphorylating ABFs and other SnRK2 substrates and reduce water depletion resulting from growth. The growth inhibition and dormancy also contribute to Ψπ-reduction in sink tissues and formation of a Ψπ-gradient in the plant, which causes water to preferentially move to sink tissues, thereby increasing drought resistance.

Leaf senescence and abscission are forms of programmed cell death. They occur slowly and are associated with efficient transfer of nutrients from the senescing leaves to the developing or storage parts of plants (34). Promotion of leaf senescence and abscission by ABA is a long-term response that allows survival of extreme drought conditions. By selection of the best transgenic survivors of extreme drought conditions, our study reveals that ABA mediates survival by promoting leaf senescence through the ABA receptor PYL9 and other PYLs, PP2C coreceptors, SnRK2 protein kinases, and ABFs and RAV1 transcription factors (Fig. S10). ABFs and RAV1 are positive regulators of ABA-induced leaf senescence (Fig. 4) (31) and overall survival. Phosphorylation of ABFs and RAV1 by SnRK2s is important for their functions in ABA-induced leaf senescence (Fig. 4) and increased survival (15). When phosphorylated by SnRK2s, RAV1 and ABFs increase the expression of NAC transcription factors through ABRE motifs and/or RAV1-binding motifs (Fig. S8C) (8). These NAC transcription factors promote the expression of downstream SAGs, which in turn, control leaf senescence (5–7, 34). The SAGs are involved in transcription regulation, protein modification and degradation, macromolecule degradation, transportation, antioxidation, and autophagy (35). The association of senescing leaves with provision of nutrients to sink tissues during drought suggests that drought survival and leaf senescence are linked by ABA signaling. This common connection through the core ABA pathway finally uncovers the underlying molecular mechanism of drought- and ABA-induced leaf senescence and its association with the ability to survive extreme drought. It must be remembered that many injury responses to drought may resemble senescence symptoms but are mediated by separate signaling pathways.

ABA promotes dormancy and growth inhibition through core ABA signaling (25). Seeds can live for many years in a deep dormancy, escaping extreme environmental conditions. Many plants, especially perennials, have a bud-to-bud lifecycle in addition to a seed-to-seed cycle. Bud dormancy is less extreme and more flexible than seed dormancy. Perennial plants can temporarily cease meristematic activity in response to the inconsistent or unusual timing of unfavorable environmental conditions (23). ABA accumulates in polar apical buds during short-day conditions, which may contribute to growth suppression and maintenance of dormancy (36). Of 146 BRC1-dependent bud dormancy genes that are putatively involved in shade-induced axillary bud dormancy, 78 are regulated during senescence (35, 37, 38). Strikingly, master positive regulators of senescence, such as ORE1, AtNAP, and MAX2/ORE9, are also up-regulated during bud dormancy, suggesting that bud dormancy is coordinated with leaf senescence to contribute to stress resistance. Most of these bud dormancy genes contain a CACGTGt motif in their promoters (37), which is recognized by ABA-related basic region-leucine zipper (b-ZIP) transcription factors (39).

Water flows from tissues with higher water potential to those with lower water potential. During drought stress, the young sink tissues but not senescing leaves can steadily decrease their water potential through osmotic adjustment, which ensures that water flows to these sink tissues (Fig. 5B). Under drought conditions, senescence of sources is, however, accompanied by growth inhibition and dormancy or paradormancy (23) in sinks, which elevate the osmolyte concentration in sinks (passive osmotic adjustment). Because the water potential of the atmosphere is extremely low under drought conditions, a relatively sealed plant surface is required to limit nonstomatal water loss. Sealing of the plant surface requires the accumulation of cuticular wax (33). ABA up-regulates wax biosynthesis genes through the core ABA signaling pathway (Fig. S9 G and H). The promotion of wax biosynthesis by ABA in buds entering dormancy may also contribute to the improved survival of pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic lines under drought conditions.

Taken together, our data and previous findings suggest that the ABA core signaling pathway plays a crucial role in survival of extreme drought by promoting stomatal closure, growth inhibition, bud dormancy, and leaf senescence. The ABA-induced dormancy-related genes and the ABA-induced senescence-related genes are largely the same genes, which are simultaneously regulated. Senescence occurs in source tissue and leads to death, whereas dormancy occurs in sink tissue and maintains life. This combination of death and life is similar to a triage strategy, and it is consistent with plant survival and therefore, species persistence during episodes of extreme environmental conditions during evolution.

Our research has generated drought-resistant pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic plants from a large-scale screening of transgenic lines and illustrated the mechanism and important role of ABA-induced leaf senescence under severe drought stress. In both Arabidopsis and rice in extreme drought conditions, the pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic lines exhibited reduced transpirational water loss, accelerated leaf senescence, reduced cell membrane damage, reduced oxidative damage, increased water use efficiency, and finally, increased survival rates. In addition to being more efficient than the 35S promoter for engineering drought-resistant transgenic plants, the RD29A promoter lacks undesirable phenotypes, including retarded growth under normal growth conditions. The enhanced drought survival of pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic plants can be further enhanced by the external application of ABA or its analogs. The combined use of pRD29A::PYL9 transgenic plants and applications of ABA or its analogs represents an effective way to protect crops from severe drought stress.

Materials and Methods

Details are provided in SI Materials and Methods, including plasmid constructs, plant materials and growth conditions, transient expression assays in Arabidopsis, drought-stress treatments, measurement of photosynthesis parameters and water loss, measurement of electrolyte leakage, determination of hydrogen peroxide level and activities of antioxidant enzymes, measurement of chlorophyll content, osmotic potential measurements, tandem affinity purification, Northern blot and real-time PCR assay, Y2H assays, and sequence comparison.

SI Materials and Methods

Plasmid Constructs.

The ORFs of the PYLs were amplified from Arabidopsis Col-0 WT cDNA and cloned into the binary vector pCAMBIA 99–1 under the control of the original CaMV 35S promoter or other promoters, including the RD29A promoter (At5g52310), GC1 promoter (At1g22690), RBCS1A promoter (At1g67090), and ROP11 promoter (At5g62880) (Dataset S2). The primers used are listed in Dataset S3, and the amplified fragments were confirmed by sequencing.

pGADT7-PP2Cs, pGADT7-MYB44, pBD-GAL4 Cam-PYLs, pHBT-PYL9, pHBT-PP2Cs, pHBT-SnRK2.6, pHBT-ABF2, ABF2S26DS86DS94DT135D, and RD29B-LUC were the same as reported (13, 18, 19, 25). ZmUBQ::GUS was provided by J. Sheen, Department of Genetics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. To generate SAG12-LUC and ORE1L-LUC constructs, the 788-bp SAG12 and 3,984-bp ORE1L promoter fragments amplified from Col-0 genomic DNA with primers SAG12proF/R and ORE1LproF/R (Dataset S3) were cloned into the BamHI and NcoI of the RD29B-LUC vector, respectively. ABI5, EEL, AREB3, ORE1, ORS1, AtNAP, and RAV1 were cloned into pHBT95 using transfer PCR with pHBT genes primers. All plasmids were confirmed by sequencing.

To generate the ProPYL9:PYL9-HA-YFP construct, the 2,566-bp PYL9 promoter fragment amplified from Col-0 genomic DNA with the primers pPYL9F and PYL9genoR (Dataset S3) was cloned into the SalI and ApaI sites of the modified pSAT vector with YFP and 3HA tags at the C terminus. The coding region of PYL9 from pCAMBIA99-1-PYL9 was then subcloned between the PYL9 promoter and the HA-YFP coding sequence. The whole insertion cassette was digested with PI-Psp1 and reinserted into pRCS2-htp binary plasmids.

Plant Materials.

The pyl8-1 mutant (SAIL_1269_A02) (19), the pyl9 mutant (SALK_083621) (17), and the snrk2.2/3/6 triple mutant (10) are in the Col-0 background. The pyl8-1, pyl9, and abi5-1 mutants were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center.

The pCAMBIA 99–1-PYLs and ProPYL9:PYL9-HA-YFP plasmids were transformed into Arabidopsis ecotype Col-0 and rice cultivar ZH11 using Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101. All transgenic plants were screened for hygromycin resistance and verified by PCR or Northern blot assays. T2 generation plants were used for the drought-stress resistance test.

Plant Growth Conditions.

Arabidopsis seeds were surface-sterilized in 20% (vol/vol) bleach for 10 min and then, rinsed four times in sterile-deionized water. Sterilized seeds were grown vertically on 0.6% Phytagel (Sigma) or horizontally on 0.3% Phytagel medium containing 1/2 Murashige and Skoog nutrients (PhytoTech) and 1% sucrose (pH 5.7) and kept at 4–8 °C for 3 d. Seedlings were grown vertically for 3 d before transfer to medium with or without the indicated concentrations of ABA (A1049; Sigma). After the seedlings were transferred to the control medium, the plates were sealed with micropore tape (3M), and the seedlings were grown horizontally in a Percival CU36L5 Incubator at 23 °C under a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod. For protoplast analysis, seedlings were grown under a relatively short photoperiod (10 h light at 23 °C and 14 h dark at 20 °C) as reported (19). For drought-stress analysis, Arabidopsis plants were grown in a growth room at 22 °C/18 °C under a 14-h light/10-h dark photoperiod with a light intensity of 100 µmol m−2 s−1, and rice plants were grown at 26 °C/22 °C under a 14-h light/10-h dark photoperiod and 75%/70% relative humidity with a light intensity of 600 µmol m−2 s−1.

Transient Expression Assay in Arabidopsis.

Assays for transient expression in protoplasts were performed as described (18). All steps were performed at room temperature. SAG12-LUC and ORE1L-LUC were used as the senescence-responsive reporters, and ZmUBQ-GUS was used as the internal control. After transfection, protoplasts were incubated in washing and incubation solution without ABA or with 5 µM ABA under light for 16 h.

Drought-Stress Treatments.

The T2 generation of transgenic Arabidopsis plants was subjected to a first-round drought-stress resistance test in soil. All seeds were imbibed at 4 °C for 2 d and planted directly in soil in 18-cm-diameter pots. Five days after seedlings emerged, each pot was thinned to eight seedlings of uniform size. Drought treatment was imposed for 20 d beginning at 10 d after seedlings emerged by withholding water; after 20 d of drought, most WT plants had died. At least three transgenic lines from each promoter–transgene combination and five pots for each line were used in this test. The positions of pots were exchanged every day to minimize the effect of environmental variability in the growth chambers. The plants were rewatered on day 31 (1 d after the 20-d drought treatment) and assessed for survival 2 d later. The second round of screening was carried out in the same manner using only those transgenic lines that were found to be relatively drought-resistant in the first round of screening.

For testing the drought resistance of transgenic rice lines, rice plants at the four-leaf stage were subjected to drought treatment for 14 d and then rewatered as needed for 14 d. To minimize environmental variability, the pots were rotated daily. The survival rate of stressed plants was recorded at 14 d after rewatering began.

Soil Water Content Analysis.

Soil water content percentage during drought treatment in Arabidopsis was measured as described (27). We used 591-mL pots (48–7214; 04.00 SQ TL TW; Myers Industries) with 130 g (∼62 g oven dry weight) Fafard Super-Fine Germinating Mix Soil (Sungro Horticultures) per pot. After being saturated with water, the total weight of the wet soil was ∼440 g per pot. Pots were covered with plastic film to reduce water loss from soil surface. Three-week-old plants (four plants per pot) were subjected to drought stress by withholding water. Plants were sprayed with 2 mL 10 µM ABA plus 0.2% Tween-20 per pot after water was withheld for 12 d. Soil water content percentage was computed as total weight minus dry soil weight divided by water weight before drought according to the work in ref. 27. For drought treatment on rice, we measured the relative water content using the Soil Temperature/Moisture Meter L99-TWS-1 (Shanghai Fotel Precise Instrument Co., Ltd) following the work in ref. 40. Before drought treatment, the mixed vermiculite and sandy soil (Zhongfang Horticulture Co.) for rice was saturated with water, and the relative soil water content before drought was set as 100%. Rice plants at the four-leaf stage were subjected to drought by withholding water for 14 d, and the relative soil water content after the drought treatment was ∼20%.

Measurement of Photosynthesis Parameters and Water Loss.

Photosynthesis parameters were measured as reported (18). At least four independent plants were used for each transgenic line. The experiment was repeated twice with similar results. The fresh weight of the aerial part of each plant was recorded before rewatering, and dry weight was measured after 2 d at 80 °C. Water was withheld from 2-wk-old plants for 20 d, and the aboveground materials were collected and weighed before and after drying. For determination of water loss, whole rosettes of 18-d-old plants were cut from the base and weighed at indicated time points.

Measurement of Electrolyte Leakage.

For the determination of electrolyte leakage, about 0.1 g plant leaves were placed in a flask containing 10 mL deionized water and shaken on a gyratory shaker at room temperature for 6 h at about 150 rpm. After the initial conductivity (Ci) was measured with a conductivity meter (Leici-DDS-307A), the samples were boiled for 20 min to kill the leaf tissues and completely release the electrolytes into the solution. After the samples had cooled to room temperature, the conductivity of the killed tissues (Cmax) was measured. The relative electrolyte leakage was calculated as (Ci/Cmax) ×100%.

Determination of Hydrogen Peroxide Level and Activities of Antioxidant Enzymes.

For hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content measurement, water was withheld from 2-wk-old plants for 14 d, and the leaves were collected. For antioxidant enzyme activities, water was withheld from 3-wk-old plants for 10 d.

For H2O2 content quantification, 1 mL plant extract in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) was mixed with 1 mL 0.1% (wt/vol) titanium sulfate [in 20% (vol/vol) H2SO4] for 10 min. After centrifugation at 15,294 × g for 10 min, the absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 410 nm using a standard curve generated with known concentrations of H2O2 as a control. The concentration of proteins was quantified using the Bradford method. Catalase (EC 1.11.1.6), superoxide dismutase (EC 1.15.1.1), and peroxidase (EC 1.11.1.7) activities were analyzed as described previously (41).

Measurement of Chlorophyll Content.

Four-week-old Arabidopsis plants in soil were sprayed with 20 µM ABA plus 0.2% Tween-20. Rice plants in soil were sprayed with 100 µM ABA plus 0.2% Tween-20. After the fresh weight of samples was determined, samples were quick-frozen, ground in liquid nitrogen, and then, homogenized in extraction buffer containing ethanol, acetone, and H2O in a ratio of 5:5:1. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 4 h and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 5 min. The absorbance of the clear supernatant was measured at wavelengths of 645 nM (D645) and 663 nM (D663) using a plate reader (Wallac VICTOR2 Plate Reader) with filters at 642 and 665 nm, respectively. The concentrations of chlorophyll pigments were calculated as follows: concentration (milligrams per liter) = 20.2 × D645 + 8.02 × D663.

Tandem Affinity Purification.

Ten-day-old seedlings of the transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing ProPYL9:PYL9-HA-YFP (Fig. S7A) were used for tandem affinity purification. Seedlings (3–4 g fresh weight) were treated for 1 h with 1/2 Murashige and Skoog medium containing 100 µM ABA or 30 min with 1/2 Murashige and Skoog medium containing 0.8 M mannitol; for the control, seedlings were treated with 1/2 Murashige and Skoog medium for 1 h. After treatment, samples were quickly frozen, ground in liquid N2, homogenized in an equal volume of 2× immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (100 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.2% Nonidet P-40, 2× protease mixture; Roche), and then, centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was passed through a 0.2-µM filter and centrifuged again at 30,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. After that, the supernatant was incubated with 40 µL 50% (vol/vol) slurry of monoclonal anti-HA agarose with antibody produced in mouse (A2095; Sigma), which was prebalanced with 1× IP buffer. The mixture was inverted for 1 h at 4 °C on a shaker. The agarose was then washed four times with 1× IP buffer, three times with high NaCl buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA), and finally, three times with 1× IP buffer. The protein that had bound to the anti-HA agarose was eluted by HA peptide (ab13835; Abcam) with a concentration of 0.5 µg/µL in 200 µL 1× IP buffer overnight at 4 °C. The supernatant was then incubated with 20 µL 50% (vol/vol) slurry of GFP-Trap Agarose (gta-20; Chromotek), which was prebalanced with 1× IP buffer. The mixture was inverted for 1 h at 4 °C on a shaker. The GFP-Trap Agarose was washed four times with 1× IP buffer and then, five times with 1× PBS buffer. Finally, the PYL9-associated proteins on the GFP-Trap Agarose were identified by MS analyses (Dataset S1).

Northern Blot and Real-Time PCR Assay.

Northern blot and real-time PCR were performed as reported (18). For Northern blot analysis, the probe was labeled with the PCR-DIG Probe Synthesis Kit (Roche). RD29A-F and PYL9-R were used for the PCR (Dataset S3). For real-time PCR, reactions were performed with iQ SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad). The primers used are listed in Dataset S3. Quantitative RT-PCR was conducted on mature leaves of 4-wk-old Arabidopsis plants that were growing in soil and sprayed with 20 µM ABA.

Rice plants in soil were sprayed with 100 µM ABA plus 0.2% Tween-20. Quantitative RT-PCR was conducted on third oldest leaves of rice plants that were growing in soil and sprayed with 100 µM ABA.

Y2H Assays.

Y2H assays were performed as described (18). pBD-GAL4-PYLs were the same as reported (13). PYL9 and PYL8 fused to the GAL4-DNA-binding domain were used as baits. PP2Cs and MYB44 fused to the GAL4-activating domain were used as prey.

Sequence Comparison.

ABF2 homologs were obtained from The Arabidopsis Information Resource (www.arabidopsis.org). Protein sequences were aligned using ClustalX 2.0.5 with the default settings (Dataset S1) and viewed using GeneDoc software (www.nrbsc.org/gfx/genedoc/).

Osmotic Potential Measurements.

Plant samples were collected in a plastic centrifuge tube filter (without membrane; Corning Costar Spin-X) and then, quick-frozen in liquid nitrogen. After thawing, the sap was collected by centrifuging at 16,000 × g for 4 min to remove insoluble material. A 10-µL volume of cell sap was measured using a vapor pressure osmometer (Model 5200; Wescor). Solute concentration was converted to osmotic potential (Ψπ) using the van’t Hoff law: Ψπ = −RTc, where c is the molar solute concentration (osmolality; moles kilogram−1), R is the gas constant (0.08314 L Bar mol−1 K−1), and T is the temperature in Kelvin.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grant R01GM059138 (to J.-K.Z.), a Chinese Academy of Sciences grant (to J.-K.Z.), National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 31370302 (to Z.C.), Knowledge Innovative Key Program of CAS Grant Y329631O0263 (to Z.C.), and Sino-Africa Joint Research Project Grant SAJC201324 (to Z.C.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1522840113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rivero RM, et al. Delayed leaf senescence induces extreme drought tolerance in a flowering plant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(49):19631–19636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709453104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim PO, Kim HJ, Nam HG. Leaf senescence. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2007;58:115–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munné-Bosch S, Alegre L. Die and let live: Leaf senescence contributes to plant survival under drought stress. Funct Plant Biol. 2004;31(3):203–216. doi: 10.1071/FP03236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gan S, Amasino RM. Inhibition of leaf senescence by autoregulated production of cytokinin. Science. 1995;270(5244):1986–1988. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5244.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JH, et al. Trifurcate feed-forward regulation of age-dependent cell death involving miR164 in Arabidopsis. Science. 2009;323(5917):1053–1057. doi: 10.1126/science.1166386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balazadeh S, et al. ORS1, an H2O2-responsive NAC transcription factor, controls senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant. 2011;4(2):346–360. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo Y, Gan S. AtNAP, a NAC family transcription factor, has an important role in leaf senescence. Plant J. 2006;46(4):601–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakuraba Y, et al. Phytochrome-interacting transcription factors PIF4 and PIF5 induce leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4636. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang C, et al. OsNAP connects abscisic acid and leaf senescence by fine-tuning abscisic acid biosynthesis and directly targeting senescence-associated genes in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(27):10013–10018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321568111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujii H, Zhu JK. Arabidopsis mutant deficient in 3 abscisic acid-activated protein kinases reveals critical roles in growth, reproduction, and stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(20):8380–8385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903144106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riov J, Dagan E, Goren R, Yang SF. Characterization of abscisic Acid-induced ethylene production in citrus leaf and tomato fruit tissues. Plant Physiol. 1990;92(1):48–53. doi: 10.1104/pp.92.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weaver LM, Gan S, Quirino B, Amasino RM. A comparison of the expression patterns of several senescence-associated genes in response to stress and hormone treatment. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;37(3):455–469. doi: 10.1023/a:1005934428906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park SY, et al. Abscisic acid inhibits type 2C protein phosphatases via the PYR/PYL family of START proteins. Science. 2009;324(5930):1068–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.1173041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma Y, et al. Regulators of PP2C phosphatase activity function as abscisic acid sensors. Science. 2009;324(5930):1064–1068. doi: 10.1126/science.1172408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furihata T, et al. Abscisic acid-dependent multisite phosphorylation regulates the activity of a transcription activator AREB1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(6):1988–1993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505667103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hao Q, et al. The molecular basis of ABA-independent inhibition of PP2Cs by a subclass of PYL proteins. Mol Cell. 2011;42(5):662–672. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antoni R, et al. PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE1-LIKE8 plays an important role for the regulation of abscisic acid signaling in root. Plant Physiol. 2013;161(2):931–941. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.208678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Y, et al. The unique mode of action of a divergent member of the ABA-receptor protein family in ABA and stress signaling. Cell Res. 2013;23(12):1380–1395. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao Y, et al. The ABA receptor PYL8 promotes lateral root growth by enhancing MYB77-dependent transcription of auxin-responsive genes. Sci Signal. 2014;7(328):ra53. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Y, Costa A, Leonhardt N, Siegel RS, Schroeder JI. Isolation of a strong Arabidopsis guard cell promoter and its potential as a research tool. Plant Methods. 2008;4(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z, Kang J, Sui N, Liu D. ROP11 GTPase is a negative regulator of multiple ABA responses in Arabidopsis. J Integr Plant Biol. 2012;54(3):169–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2012.01100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chattopadhyay S, Ang LH, Puente P, Deng XW, Wei N. Arabidopsis bZIP protein HY5 directly interacts with light-responsive promoters in mediating light control of gene expression. Plant Cell. 1998;10(5):673–683. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.5.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volaire F, Norton M. Summer dormancy in perennial temperate grasses. Ann Bot (Lond) 2006;98(5):927–933. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcl195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhaskara GB, Nguyen TT, Verslues PE. Unique drought resistance functions of the highly ABA-induced clade A protein phosphatase 2Cs. Plant Physiol. 2012;160(1):379–395. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.202408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujii H, et al. In vitro reconstitution of an abscisic acid signalling pathway. Nature. 2009;462(7273):660–664. doi: 10.1038/nature08599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao M, et al. An ABA-mimicking ligand that reduces water loss and promotes drought resistance in plants. Cell Res. 2013;23(8):1043–1054. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okamoto M, et al. Activation of dimeric ABA receptors elicits guard cell closure, ABA-regulated gene expression, and drought tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(29):12132–12137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305919110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olsen AN, Ernst HA, Leggio LL, Skriver K. DNA-binding specificity and molecular functions of NAC transcription factors. Plant Sci. 2005;169(4):785–797. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JH, Chung KM, Woo HR. Three positive regulators of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis, ORE1, ORE3 and ORE9, play roles in crosstalk among multiple hormone-mediated senescence pathways. Genes Genomics. 2011;33(4):373–381. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng CZ, et al. Arabidopsis RAV1 transcription factor, phosphorylated by SnRK2 kinases, regulates the expression of ABI3, ABI4, and ABI5 during seed germination and early seedling development. Plant J. 2014;80(4):654–668. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woo HR, et al. The RAV1 transcription factor positively regulates leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2010;61(14):3947–3957. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen LQ, et al. Sucrose efflux mediated by SWEET proteins as a key step for phloem transport. Science. 2012;335(6065):207–211. doi: 10.1126/science.1213351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samuels L, Kunst L, Jetter R. Sealing plant surfaces: Cuticular wax formation by epidermal cells. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:683–707. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.103006.093219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uauy C, Distelfeld A, Fahima T, Blechl A, Dubcovsky J. A NAC Gene regulating senescence improves grain protein, zinc, and iron content in wheat. Science. 2006;314(5803):1298–1301. doi: 10.1126/science.1133649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buchanan-Wollaston V, et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals significant differences in gene expression and signalling pathways between developmental and dark/starvation-induced senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2005;42(4):567–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruttink T, et al. A molecular timetable for apical bud formation and dormancy induction in poplar. Plant Cell. 2007;19(8):2370–2390. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.052811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.González-Grandío E, Poza-Carrión C, Sorzano CO, Cubas P. BRANCHED1 promotes axillary bud dormancy in response to shade in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25(3):834–850. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.108480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Graaff E, et al. Transcription analysis of Arabidopsis membrane transporters and hormone pathways during developmental and induced leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 2006;141(2):776–792. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.079293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen Q, Ho TH. Functional dissection of an abscisic acid (ABA)-inducible gene reveals two independent ABA-responsive complexes each containing a G-box and a novel cis-acting element. Plant Cell. 1995;7(3):295–307. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jin R, et al. Physiological changes of purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.) after progressive drought stress and rehydration. Sci Hortic (Amsterdam) 2015;194:215–221. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shi H, Ye T, Zhu J-K, Chan Z. Constitutive production of nitric oxide leads to enhanced drought stress resistance and extensive transcriptional reprogramming in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2014;65(15):4119–4131. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.