Significance

Scientists have developed many affinity pulldown methods to characterize protein networks. Three persistent challenges with current approaches are capturing labile interactions, isolating insoluble DNA-bound complexes, and preserving modifications potentially important for binding specificity. This report presents a cross-linked affinity approach to meet these challenges and effectively capture interactions that otherwise may be intractable with native affinity techniques. We isolate several Drosophila and human protein complexes to demonstrate the technique’s scalability across a range of initial cell amounts and sources, and we develop the ability to identify the breadth of associated histone and nonhistone modifications in parallel. Our results indicate that cross-linked affinity pulldowns should be broadly useful for comprehensive analyses of chromatin networks.

Keywords: chromatin complexes, affinity pulldown, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, BioTAP-XL, histone modifications

Abstract

Posttranslational modifications (PTMs) are key contributors to chromatin function. The ability to comprehensively link specific histone PTMs with specific chromatin factors would be an important advance in understanding the functions and genomic targeting mechanisms of those factors. We recently introduced a cross-linked affinity technique, BioTAP-XL, to identify chromatin-bound protein interactions that can be difficult to capture with native affinity techniques. However, BioTAP-XL was not strictly compatible with similarly comprehensive analyses of associated histone PTMs. Here we advance BioTAP-XL by demonstrating the ability to quantify histone PTMs linked to specific chromatin factors in parallel with the ability to identify nonhistone binding partners. Furthermore we demonstrate that the initially published quantity of starting material can be scaled down orders of magnitude without loss in proteomic sensitivity. We also integrate hydrophilic interaction chromatography to mitigate detergent carryover and improve liquid chromatography-mass spectrometric performance. In summary, we greatly extend the practicality of BioTAP-XL to enable comprehensive identification of protein complexes and their local chromatin environment.

Chromatin encompasses the subset of proteins and RNAs in complex with DNA to form the chromosomes within eukaryotic nuclei. As the primary protein constituents of chromatin, histones organize genomic DNA into nucleosomes and display an extensive array of posttranslational modifications (PTMs) (1). It is increasingly evident that specific histone PTMs are selectively recognized by specific nonhistone proteins that are themselves regulators of many nuclear events such as epigenetic silencing (2, 3). Consequently, defects in these chromatin components often manifest in a number of human diseases (4).

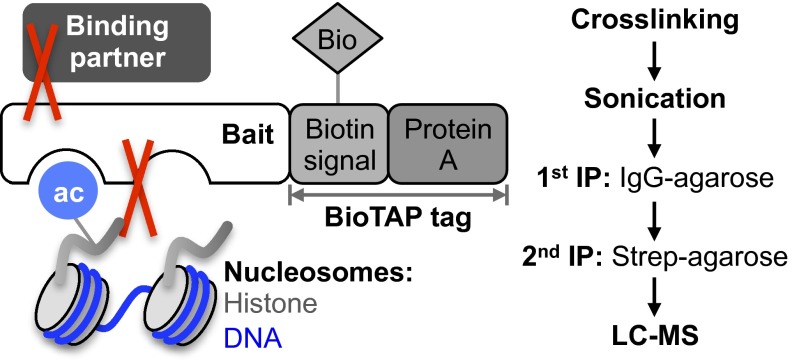

As specific interactions between modified histones and nonhistone proteins help distinguish complexes participating in distinct processes, the identification of protein and modification-dependent interactions provides key insights into chromatin biology. Various chromatography and pulldown methods have been developed to identify binding partners. In a typical native pulldown experiment, nuclei from hypotonically lysed cells are digested with micrococcal nuclease (MNase). Extracted chromatin is subjected to immunoprecipitation to isolate the desired complexes. If using a tag such as FLAG, complexes are then competitively eluted and identified. Several drawbacks to native pulldowns as described here are that MNase leaves behind a substantial insoluble nuclear pellet and degrades associating RNAs, that salt extraction of the digested nucleosomes risks dissociation of the tagged bait from its interacting partners, and that most tags do not have sufficient affinity for their respective antibody to permit highly stringent washes. The result is often an incomplete picture of the chromatin-bound complex. BioTAP-XL is a technique that complements native pulldowns. BioTAP-XL uses formaldehyde to inactivate endogenous enzymes and to cross-link labile interactions with the bait, sonication to solubilize the genomic chromatin content, and high affinity tags to capture the bait and its associated factors (Kd = 10−9 and 10−15 M for the bipartite BioTAP tag compared with 10−8 M for the FLAG tag). Thus, BioTAP-XL captures interactions that may be inaccessible or disrupted using native pulldowns.

BioTAP-XL has successfully identified key interactors of the male-specific lethal (MSL) dosage compensation and heterochromatin protein (HP1a) complexes in Drosophila (5) and revealed novel components of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 in human tissue culture cells (6) and fruit flies (7). Despite the aforementioned advantages, BioTAP-XL suffers from several limitations. First, the cell number requirement far exceeds the amounts typically used in standard affinity experiments, namely with 108 cells for native pulldowns (8) compared with 1010 cells for BioTAP pulldown (9). Second, the high detergent concentrations used during the procedure risks interfering with liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS). Third, our analysis of the associated histone PTMs is complicated by both the nearly irreversible binding of the tagged complexes to streptavidin and the inability to obtain histone peptides of comparable ionization efficiencies across modified states using trypsin alone.

We sought to address these limitations using Drosophila and human cells expressing BioTAP-tagged factors. To demonstrate scalability, we performed parallel tandem affinity pulldowns of the same bait across various initial chromatin amounts. We recovered the core interactors of MSL3 at even the lowest tested amount of Drosophila cells. To improve detergent removal, we compared a sample processed either with conventional spin columns or hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC). We observed significant improvement in LC-MS quality of the MSL3 elutions prepared using HILIC over spin columns. To facilitate histone modification analysis, we derivatized the associated histones directly on the streptavidin beads. We successfully quantified histone modifications enriched with MSL3 and HP1a from Drosophila cells and with chromobox homolog 4 (CBX4) and bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) from human cells. In short, this report streamlines BioTAP-XL for biochemically characterizing chromatin complexes and their associated histone modifications.

Results

Scalability of BioTAP Pulldown: MSL3 Complex.

One challenge of implementing the previously published BioTAP-XL protocol (Fig. 1) (9) was acquiring enough cell material for the pulldowns. Indeed the initially reported amounts were nearly 100-fold higher than the amounts used in typical native pulldown experiments. To extend the practicality of BioTAP-XL, we sought to scale the procedure down for more manageable initial chromatin amounts.

Fig. 1.

Overview of BioTAP-XL tandem affinity pulldown. In the last stage of the pulldown, the BioTAP-tagged bait is bound to streptavidin beads. Both the binding partners and histones cross-linked to the bait can be analyzed by LC-MS.

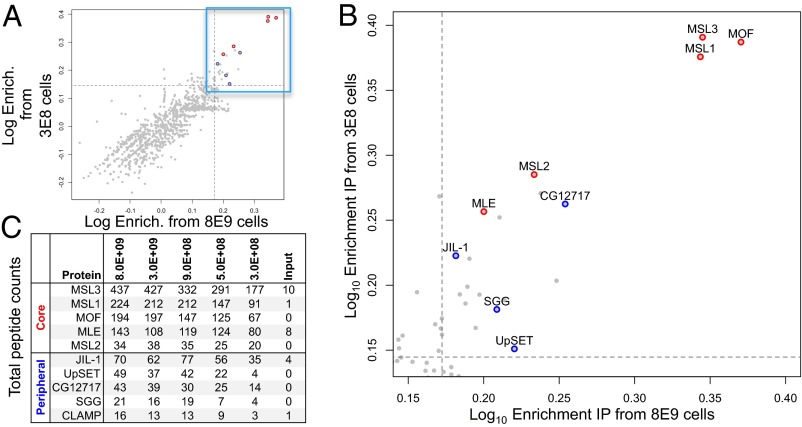

We affinity purified BioTAP-tagged MSL3 from S2 Schneider cells, which are essentially male based on the lack of observable Sxl protein. Previously, our group identified MSL3 associated proteins using large-scale amounts (5). To determine the proteins enriched by the pulldown, we first normalized the total peptide counts for each protein (Dataset S1) to the protein length and to the total number of peptides identified across all proteins in the LC-MS experiment (10) before comparing the pulldown with the input.

We recovered MSL3 bait and all other core dosage compensation components (MSL1, MSL2, MLE, and MOF) as major binding partners across all cell amounts tested (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1). With less input, the pulldowns generally yielded fewer total peptides. MSL3 most strongly enriches for MOF and MSL1 among the core components, and this association has been recapitulated with protein coexpression in Sf9 cells (11). It is notable that we successfully identified MLE across the BioTAP experiments. Native pulldowns often encounter difficulty in obtaining MLE due to insufficient protection of roX RNAs that stabilize its association with the other core components (12). Formaldehyde sufficiently inactivates ribonucleases without addition of RNase inhibitors. Beyond the core subunits, we also recovered CG12717, JIL-1, SGG, UpSET, and CLAMP. These components have been recovered in other large-scale pulldowns and represent peripheral binding partners that may participate in dosage compensation without necessarily binding directly to the bait. Indeed proximity ligation experiments indicate that JIL-1 contacts both MSL1 and MSL2 but not MSL3 (13).

Fig. 2.

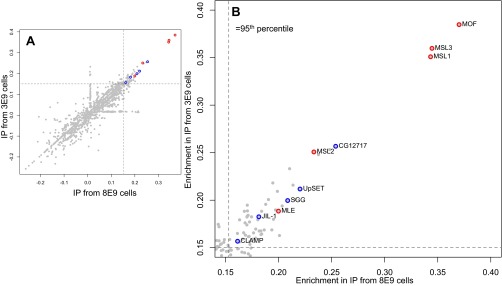

MSL3 binding partners. (A) Protein enrichments from BioTAP pulldown of MSL3 relative to input using a starting culture amount of 8 × 109 (x axis) and 3 × 108 cells (y axis), which are respectively the largest and smallest S2 cell numbers tested. Dots represent identified proteins and dashed lines represent the 97th percentile of enriched proteins from both IPs. (B) Zoomed-in view of region bounded by both cutoffs (blue box in A) containing proteins jointly enriched in both pulldowns from the largest and smallest cell numbers tested. Proteins in red are core dosage compensation components, whereas proteins in blue are peripheral MSL3 binding partners. (C) Total peptide counts of core and peripheral MSL3 binding partners across cell amounts. Note CLAMP is not found within the 97th percentile boundary. See Fig. S1, where CLAMP is jointly enriched at the 95th percentile boundary by the largest (8 × 109 cells) and second largest (3 × 109 cells) pulldowns.

Fig. S1.

MSL3 binding partners from larger scale amounts. (A) Protein enrichments from BioTAP pulldown of MSL3 relative to input using 8 × 109 cells (x axis) and 3 × 109 (y axis) starting cells amounts. Note that the y axis is from an IP with 10× more cells than in Fig. 2. Dots represent identified proteins and dashed lines represent the 95th percentile of enriched proteins. (B) Zoomed-in region of most enriched MSL3 binding proteins. Proteins in red are core dosage compensation components, whereas proteins in blue are peripheral MSL3 binding partners.

Although we recovered the expected binding partners of MSL3 with pulldowns from both the largest (8 × 109) and smallest (3 × 108) input cell numbers, there were other enriched factors. Several proteins are commonly enriched by the BioTAP-XL pulldown independently of bait identity and are likely to represent false positives. For instance, both E(bx) (also known as NURF301) and CtBP were recovered with BioTAP-tagged HP1 (5) and MSL3 (Dataset S1), although we would expect few shared binding partners. Considering this observation, we believe that performing multiple pulldowns using different baits from either the same or a different complex will minimize misinterpretation of BioTAP-XL data.

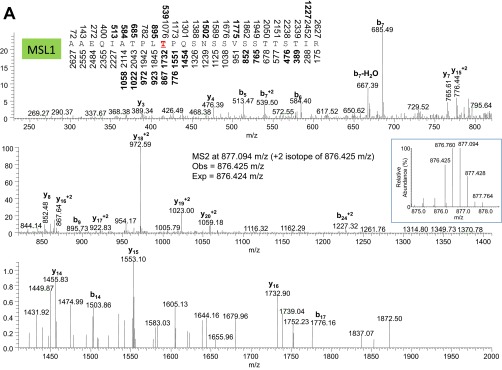

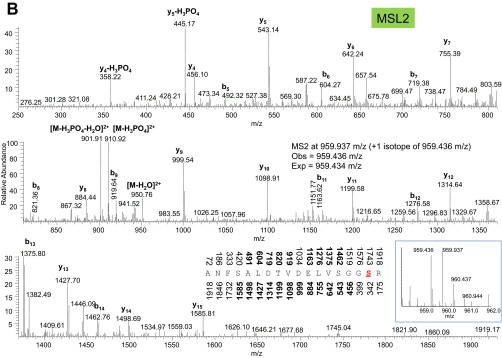

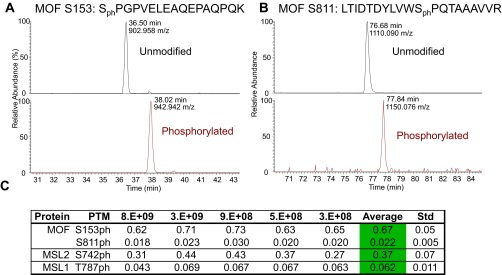

We also recovered consistent levels of MSL1, MSL2, and MOF phosphorylation across the BioTAP-tagged MSL3 pulldowns (Figs. S2 and S3). Two of the modifications we identified (MOF S153ph and MSL2 S742ph) have been documented in another phospho-proteomic survey (14). The relative abundances of the modifications found in our study span a wide range, from MOF S153ph at 67 ± 5% to S811ph at 2.2 ± 0.5% of total MOF protein. That these levels remained consistent suggests that the sensitivity in quantifying modifications of the core dosage compensation components is not impaired across different starting cell amounts. For other factors in other systems, scalability is likely conditional on both the extent of bait expression and incorporation into chromatin. Namely, a lower input amount would be sufficient for a cell line that expresses a bait with extensive chromatin incorporation, whereas incorporation at a lower efficiency regardless of overall bait expression would require a higher input amount.

Fig. S2.

Tandem mass spectra from collisional induced dissociation of phosphorylated peptides from MSL1 (A), MSL2 (B), and MOF (C and D) collected in the ion trap. Nominal masses above and below the peptide sequence are bolded if the b and y fragment ion, respectively, were identified in the MS/MS. Expected and observed precursor ion masses in the MS1 from the Orbitrap are also provided. (Insets) MS1 precursor ion distributions. The phosphorylated amino acid in the peptide sequence is colored red and underlined.

Fig. S3.

Relative quantification of MOF, MSL2, and MSL1 phosphorylation. (A) Extracted ion chromatogram (XIC) of MOF 153–169 peptide unmodified (black trace) and phosphorylated (red trace) at S153. Observed retention time and precursor m/z are labeled. (B) XIC of MOF 801–820 peptide unmodified and phosphorylated at S811, similar to A. (C) Relative quantification of MOF phosphorylation across BioTAP pulldowns at various cell amounts with expected precursor m/z provided. Residue position does not include start methionine.

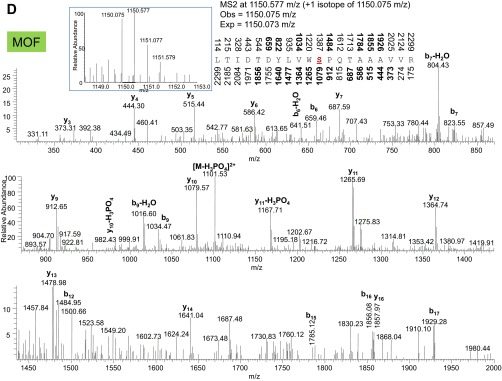

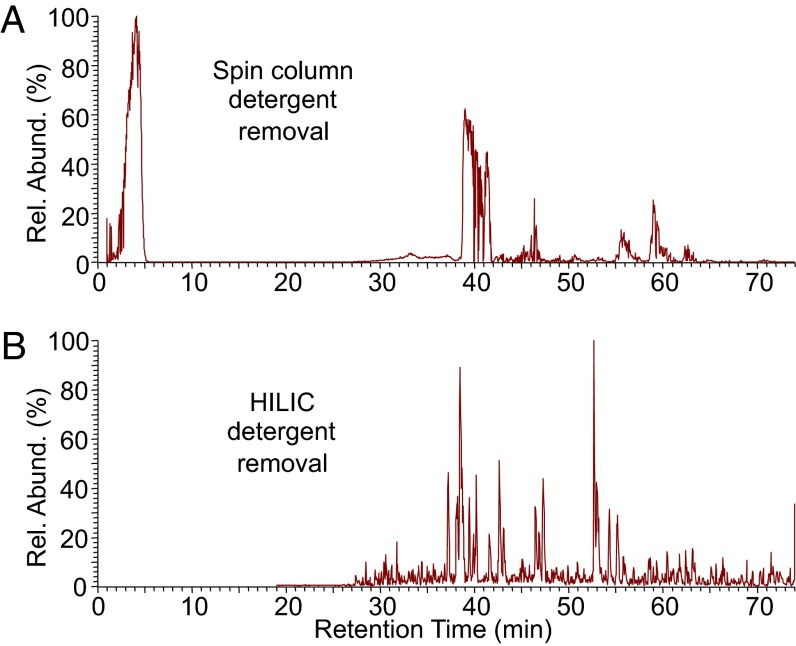

Use of HILIC for BioTAP Input and IgG Elution: MSL3 Complex.

In reducing the chromatin amounts, we were concerned about the increasingly negative effects that detergents would have with respect to trypsin activity and LC-MS quality. BioTAP-XL involves initial binding with IgG beads, followed by Triton-SDS washes, urea-SDS elution, and capture with streptavidin beads (Fig. 1). In situations when there is low biotinylation, one can recover the bait and associated proteins in the streptavidin flow-through (essentially IgG elution). However, to analyze either input or IgG elutions, when proteins of interest are not bound to beads, detergent removal from either sample is not straightforward.

Previously, we used detergent-removal spin columns to prepare the input and IgG-eluted samples. Magnetic beads typically reserved for DNA preparations were recently demonstrated to also adsorb proteins (15). The mechanism is based on hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) (16). Under HILIC conditions, proteins in the organic phase partition into the aqueous layer surrounding the magnetic bead surface, whereas detergents remain in the supernatant and are washed away with organic solvent. In contrast, spin columns bind detergents and leave proteins in the flow-through.

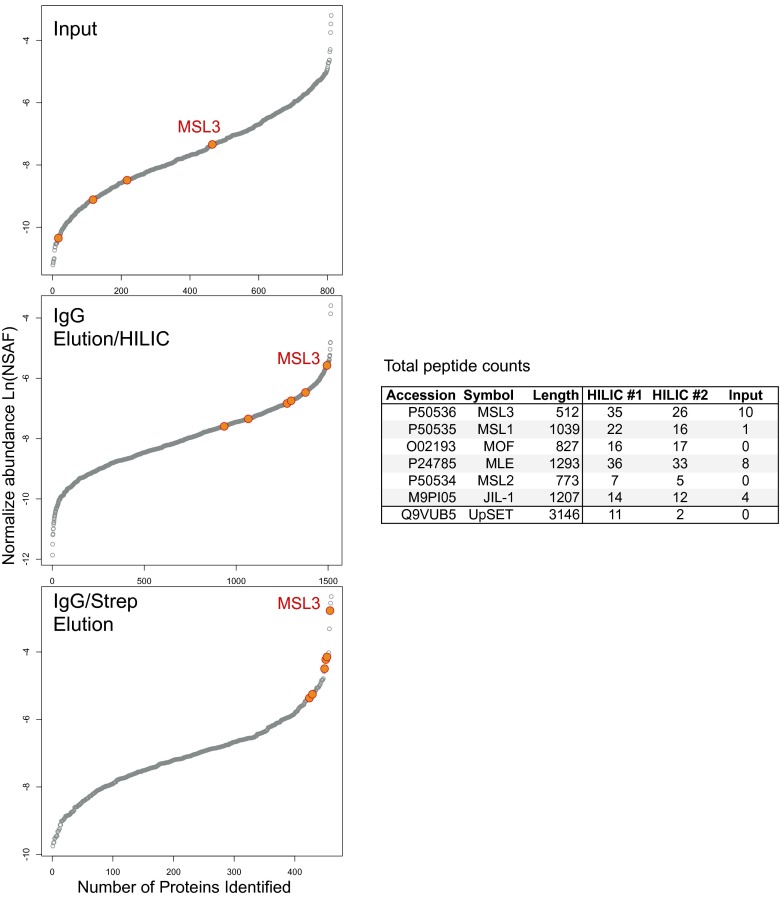

We believe that HILIC is especially suitable for BioTAP-XL because the input and IgG-eluted samples are already denatured and would more efficiently partition onto the beads. We prepared an IgG-eluted sample of tagged MSL3 that contains SDS with either spin columns or magnetic beads. The HPLC trace showed improved chromatography of the HILIC samples compared with the spin column samples (Fig. 3), and we confirmed enrichment of the core MSL3 binding partners (Fig. S4). Because the HILIC samples originated from a single IgG elution, we expected less enrichment compared with samples from tandem IgG/Strep elutions, which is the standard BioTAP-XL method.

Fig. 3.

Improvement of LC-MS with HILIC. (A) MS1 base ion peak of the BioTAP-tagged MSL3 sample eluted after IgG pulldown and cleaned with a centrifugal unit. (B) Similar to A except IgG-elution was cleaned with HILIC magnetic beads. Note the difference in overall profile with many more discrete peaks across 25–70 min in the magnetic bead prepared sample.

Fig. S4.

Normalized spectral abundance of identified proteins (gray circles) in Input, IgG elution, and tandem IgG/Strep elution of BioTAP-tagged MSL3 from S2 cells. Proteins are ordered from least to most abundant (based on normalized spectral abundance) in each panel (left to right). MSL3, MSL1, MSL2, MLE, MOF, and JIL-1 are highlighted (orange circles, with MSL3 labeled). Note the progressive increase in relative abundance of the dosage compensation components with each affinity pulldown compared with input. Total peptide counts from the HILIC processed IgG elutions are provided.

On-Bead Derivatization for BioTAP Histone PTM Analysis: Drosophila MSL3/HP1a and Human BRD4/CBX4 Complexes.

In contrast to the analysis of most proteins associated with BioTAP-tagged baits, analysis of the extensively modified histones presents a unique challenge for standard proteomics. Derivatization with propionic anhydride is one approach to facilitate histone analysis that has been used by various groups (17–22). The anhydride reaction protects unmodified and monomethylated lysines from trypsin cleavage and increases overall hydrophobicity. Consequently, trypsin digestion yields peptides of similar ionization efficiencies across lysine modifications and of sufficient hydrophobicity to be retained on reversed phase columns. In this manner, histone peptides can be observed and quantified by chromatographic peak integration within a given sample.

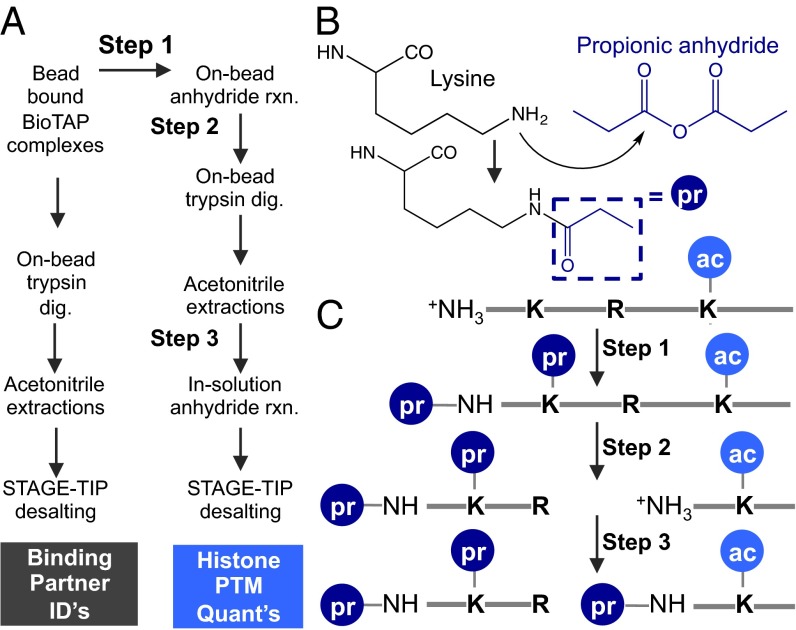

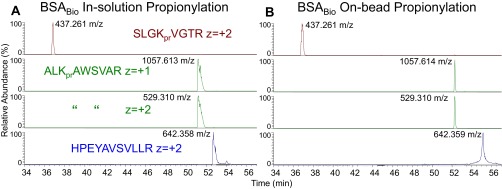

The anhydride reaction proceeds with fractionated or pooled histones (23). The reaction also proceeds with histones in-solution or in-polyacrylamide gel (24). We hypothesized that the reaction could also occur on histones associated with BioTAP-tagged bait bound to streptavidin-agarose (Fig. 4). Treating the histones directly on-bead minimizes sample losses from inefficient recovery of histones boiled off streptavidin-agarose and extracted from polyacrylamide gels. To test whether the beads would quench the anhydride reagent, we performed separate reactions of biotinylated-BSA (BSABio) bound to streptavidin-agarose or in solution. We observed the same propionylated BSABio peptides in both instances (Fig. S5). This finding suggests that the anhydride reaction can proceed with protein substrates in-solution, in-gel, or on-bead.

Fig. 4.

Overview of histone PTM workflow with BioTAP-XL. (A) Comparing binding partner identification workflow with histone PTM quantification workflow. Following isolation of BioTAP-tagged complexes onto streptavidin beads, one adds trypsin for on-bead digestion and extracts the peptides with acetonitrile to identify binding partners. Alternatively, one can add propionic anhydride for on-bead derivatization to examine histone PTMs. (B) Mechanism of lysine side-chain (black) attacking propionic anhydride (dark blue), resulting in a propone group (pr) added. A similar mechanism occurs on the free amine of the N terminus if it is not already acetylated. (C) Schematic of first series of derivatization, which caps unmodified lysines (Step 1). Lysines already acetylated (ac) or di- and trimethylated are not reactive to anhydride. Trypsin digestion is then restricted to arginines (Step 2). A second series of derivatization caps the newly generated N termini of the peptides (Step 3).

Fig. S5.

Comparison of in-solution and on-bead anhydride reaction. (A) XIC of BSA peptides from in-solution anhydride treatment and in-solution trypsin digestion of BSABio. (B) Similar to A except peptides were from on-bead anhydride treatment and on-bead trypsin digestion of streptavidin-bound BSABio. In both cases, HPEYAVSVLLR (bottom blue trace) represents a control BSA peptide between the treatments that lacks any propone group due to lack of any lysines.

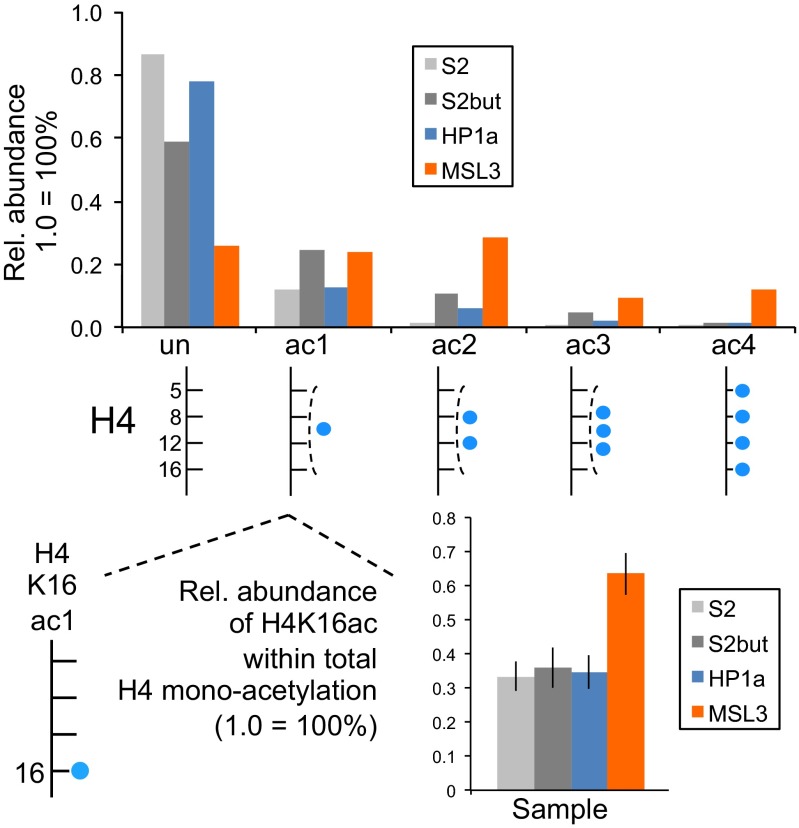

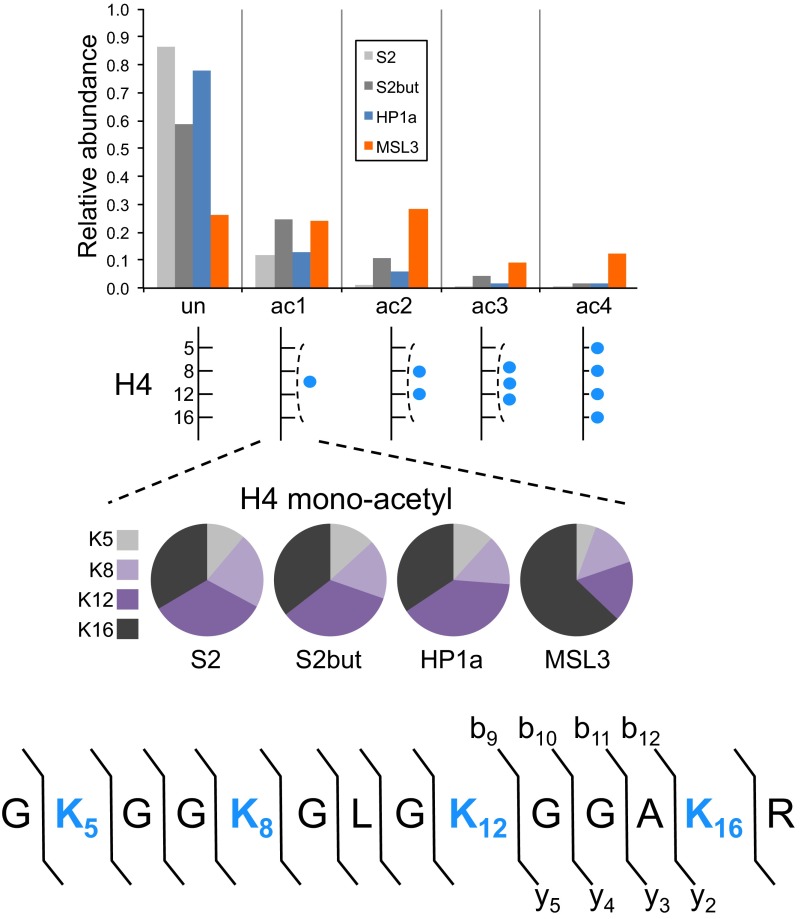

We next tested whether BioTAP-XL pulldown of a histone binder would yield histones of sufficient purity and quantity for LC-MS. We performed BioTAP-XL pulldown of MSL3 and HP1a from S2 cells. MSL3, in conjunction with the other core dosage compensation components, modifies the chromatin landscape of the male X-chromosome for transcriptional activation. HP1a localizes broadly with heterochromatin across the genome. As a reference, we also analyzed histones extracted from S2 cells and from cells treated with sodium butyrate, a histone deacetylase inhibitor that leads to overall increased acetylation levels. MSL3 BioTAP pulldown yields histones significantly enriched in H4 acetylation relative to HP1a, in a manner similar to butyrate treatment of S2 cells (Fig. 5). One notable difference is that MSL3 histones have a significantly higher proportion of H4K16 monoacetylation than HP1a histones or histones from butyrate treated cells (Fig. 5 and Fig. S6). This result is consistent with the K16 acetyltransferase specificity of MOF (12).

Fig. 5.

H4 acetylation patterns from BioTAP-XL pulldown of MSL3 and HP1a. Relative abundances (1.0 = 100%) of the number of acetyl groups (blue circle) on the 4–17 H4 peptide (GKGGKGLGKGGAKR) spanning K5, K8, K12, and K16 were determined and compared with genomic histones extracted from S2 cells and butyrate treated cells. Average fragment ion ratios (Fig. S6) from the pooled MS/MS collected across the monoacetylated H4 chromatographic peak were calculated for each sample to determine the relative levels of H4K16ac1 with respect to total H4 monoacetylation.

Fig. S6.

H4 acetylation patterns from BioTAP-XL pulldown of MSL3 and HP1a as in Fig. 5, but with estimates of H4 monoacetylation localized to K5, K8, K12, and K16. Note the increase in the proportion of H4K16 monoacetylation in the MSL3 pulldown compared with the other samples. The b and y fragment ion series of the H4 peptide used to determine the levels of H4K16 monoacetylation are labeled.

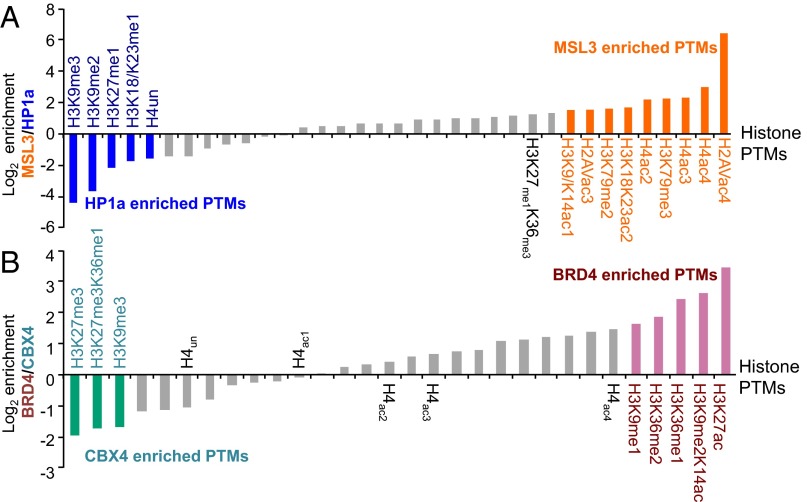

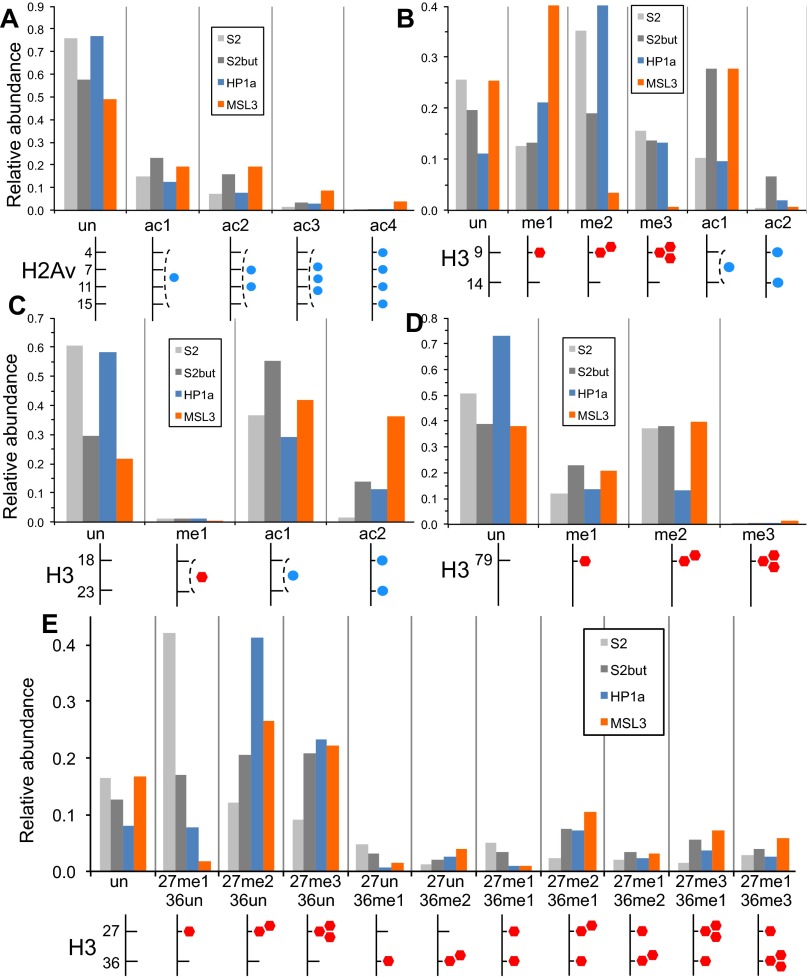

We also compared other histone modification patterns between MSL3 and HP1a pulldowns (Fig. 6A and Fig. S7). Similar to H4 acetylation, MSL3 histones were enriched in H2Av acetylation compared with HP1a histones (Fig. S7A). HP1a histones were highly enriched for H3K9 di- and trimethylation, which are both correlated with silent genes, compared with MSL3 histones (Fig. S7B). Not all methylations are associated with heterochromatin, and some PTMs such as H3K36 and H3K79 methylation are associated with active transcription. MSL3 histones were highly enriched for H3K79 methylation (Fig. S7D). There is a slightly weaker enrichment for H3K36 trimethylation (i.e., H3K27me1K36me3) (Fig. 6A and Fig. S7E). These findings of MSL3 enrichment for active PTMs such as H4K16 acetylation and H3K79 methylation using the on-bead method are consistent with an earlier report by our group using the in-gel method (25).

Fig. 6.

Histone PTM enrichment from BioTAP-XL of MSL3, HP1a, BRD4, and CBX4. (A) Histogram of various histone PTMs enriched by MSL3 and HP1a from Drosophila S2 cells. The thresholds for modifications significantly enriched by MSL3 (orange) are set at ≥1.5 and in HP1a (blue) set at ≤−1.5. Note that H3K27me1K36me3 is also relatively enriched by MSL3 but did not reach the threshold. (B) Histogram of various histone PTMs enriched by BRD4 and CBX4 from human 293-TREx cells. The thresholds for significantly enriched PTMs by BRD4 (pink) and CBX4 (teal) are the same as in A. Note the progressive enrichment for higher acetylated states of H4 (e.g., tetraacetylated H4 or H4ac4 compared with unmodified H4 or H4un) in the BRD4 pulldown.

Fig. S7.

Histone modification patterns of HP1a (blue) and MSL3 (orange) BioTAP pulldown from S2 cells. Histones from S2 (light gray) and butyrate (dark gray) treated cells are provided as reference. Relative abundance (1.0 = 100%) is plotted on y axis for each panel. Diagrams below each graph are meant to facilitate histone modification identification, with blue circles indicating acetyl groups and red hexagons indicating methyl groups. (A) Acetylation profile from the 1–19 H2Av peptide (AGGKAGKDSGKAKAKAVSR), all with N-terminal acetylation. Note the overall enrichment in hyperacetylated H2Av by MSL3 relative to HP1a. (B) Modification profile of the 9–17 H3 peptide (KSTGGKAPR) spanning H3K9 and H3K14. Note the overall enrichment for H3K9 di- and trimethylation in the HP1a histones compared with MSL3 histones, in contrast to the enrichment in H3K9/K14 monoacetylation in the MSL3 histones. (C) Modification profile of the 18–26 H3 peptide (KQLATKAAR) spanning H3K18 and H3K23. Note the overall enrichment in H3K18 and K23 acetylation in the MSL3 histones. (D) Modification profile of the 73–83 H3 peptide (EIAQDFKTDLR) spanning H3K79. Note the overall enrichment in H3K79 methylation in the MSL3 histones. (E) Modification profile of the 27–40 canonical H3 peptide (KSAPATGGVKKPHR) spanning H3K27 and H3K36. Note the increasing enrichment of higher methylated states of H3K36 in the MSL3 histones in comparing H3K27me1K36un (2nd set from left), H3K27me1K36me1 (7th set), H3K27me1K36me2 (9th set), and H3K27me1K36me3 (11th set).

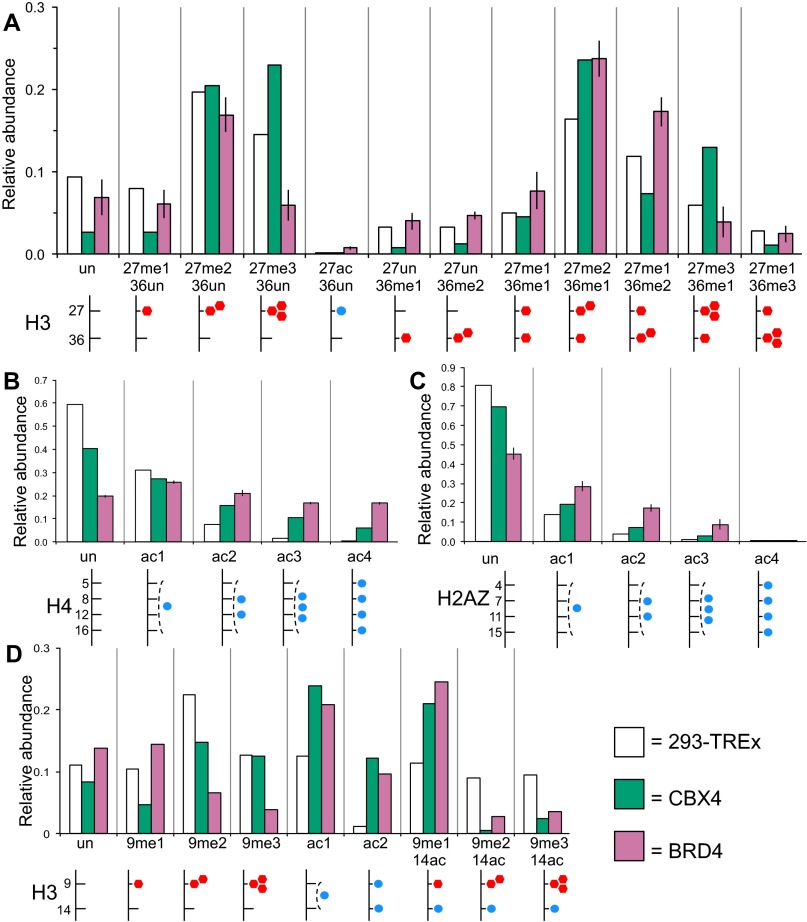

Establishing that BioTAP-XL pulldown from Drosophila S2 cells yields histones of sufficient purity and quantity for LC-MS, we next explored whether BioTAP-XL from human 293-TREx cells would also be successful for histone analysis. We compared the histone modification profiles from BioTAP-tagged CBX4 and BRD4 (Fig. 6B and Fig. S8). CBX4 is a chromodomain protein that participates in Polycomb group silencing (26), whereas BRD4 is a double-bromodomain protein that facilitates transcriptional elongation in an acetylated histone-dependent manner.

Fig. S8.

Histone modification patterns from CBX4 (teal) and BRD4 (pink) BioTAP pulldown from 293 cells. Histones extracted from 293 cells (white) are provided as a reference. Vertical lines on BRD4 columns represent SD from four replicates. Relative abundance (1.0 = 100%) is plotted on y axis for each panel. (A) Modification profile of the 27–40 canonical H3 peptide (KSAPATGGVKKPHR) spanning H3K27 and H3K36. (B) Acetylation profile from the 4–17 H4 peptide (GKGGKGLGKGGAKR), spanning H4 K5, K8, K12, and K16. (C) Acetylation profile of the 1–19 H2AZ peptide (AGGKAGKDSGKAKTKAVSR) spanning H2AZ K4, K7, K11, and K15, with N-terminal acetylation. (D) Modification profile of the 9–17 canonical H3 peptide (KSTGGKAPR) spanning H3K9 and H3K14. Note the K9/K14 293 data were from ref. 17.

BRD4 histones showed a strong enrichment for H3K27 acetylation and H3K36 methylation (Figs. 6B and Fig. S8A). We observed progressively greater enrichment for progressively acetylated states of H4 by BRD4 (Figs. 6B and Fig. S8B). In particular, there was a higher enrichment for tetraacetylated H4 than monoacetylated H4 that is consistent with a previous report (27). Because the bromodomain recognizes acetyl lysines, we believe that the apparent enrichment of H3K36 methylation is due to association between BRD4 and actively expressed gene regions marked both by H4 hyperacetylation (the likely direct binder) and H3K36 methylation. CBX4 showed a strong enrichment for both H3K27 (Figs. 6B and Fig. S8A) and H3K9 trimethylation (Fig. S8D). H3K27 trimethylation is associated with silent genes and is the product of EZH2 methyltransferase, an enzyme that also participates in Polycomb silencing. In summary, on-bead derivatization of BioTAP-tagged chromatin factors readily and comprehensively yields information on associated histone PTMs.

Discussion

This report demonstrates the versatility of BioTAP-XL in characterizing chromatin interactions and both histone and nonhistone modifications. We have built upon our previous method to improve the capture and quantification of histone posttranslational modifications, overall performance of samples for LC-MS, and the requisite scale of starting nuclear material. A key aspect of BioTAP-XL is the use of formaldehyde. Indeed, the advantages of formaldehyde, namely its broad reactivity to amine-containing substrates, permeability, and small size, have been exploited for many chromatin studies that specifically examine protein:protein (28) and protein:DNA (29) interactions. We also believe that cross-linking is particularly useful for experiments involving whole tissues or animals where endogenous phosphatases and deacetylases can be inactivated. A previous report found that non-cross-linked and formaldehyde cross-linked proteins yielded comparable mass spectrometric signals, whereas reversal of cross-links with heat and detergent significantly attenuated the signal (30). In the BioTAP-XL experiments, we do not reverse the cross-links because this evidently does not improve peptide recovery and would introduce additional detergents.

There are several remaining challenges with BioTAP-XL. First, not all chromatin complexes can be isolated with formaldehyde (31). It remains to be tested whether cross-linkers such as disuccinimidyl glutarate that span greater intermolecular distances and stabilize formaldehyde refractory complexes are compatible with the BioTAP method. Second, the BioTAP-tag is ∼17 kDa and larger than most affinity tags. One can potentially miniaturize the BioTAP-tag by substituting smaller domains that exhibit comparable IgG and streptavidin affinities as the full-length tag. Third, the smallest input we tested (108 cells) still exceeds the amounts obtained from experiments such as flow sorting (105 to 106 cells). Further scaling will depend on optimizing bait expression and incorporation within chromatin, potentially with Cas9-mediated introduction of the BioTAP-tag into the endogenous gene (32), and on improving peptide detection and fragmentation efficiency within the mass spectrometer.

Fourth, as with all pulldown approaches from cell extracts, BioTAP-XL has difficulty in parsing direct from indirect interactions, for instance whether the bait or a binding partner in the same complex is a direct histone PTM binder. This complexity is further compounded by mononucleosomes containing two copies of the core histones that can each bear distinct PTMs (33). We propose that the ability to recover indirect interactions through sonication, which leads to a range of fragment sizes spanning multiple nucleosomes, is in fact of practical interest, as it is the local chromatin neighborhood that reflects the regulatory function. Furthermore, as it is possible that directly bound modifications might be occluded by binding and cross-linking to the bait, the identification of associated modifications may require the recovery of neighboring nucleosomes.

Regarding these shortcomings, identifying direct binding events will require follow-up with in vitro binding assays between defined peptide modifications and reconstituted complexes. Other orthogonal experiments such as yeast two-hybrid assays would also be invaluable in validating candidate binding partners. A future improvement would be to use cross-linkers that can be fragmented independently from the peptide backbone in the mass spectrometer (34). With such cross-linkers, the previously joined peptides could be individually sequenced to yield the direct protein contacts governing the overall complex architecture. Notwithstanding these challenges, the advancements made with BioTAP-XL in this report should greatly streamline investigations into how distinct complexes of specific protein components and histone modifications may engage in distinct chromatin processes.

Experimental Procedures

BioTAP-XL Protocol and LC-MS Analysis.

Two liters of S2 cells at 8–9 × 106 cells per mL that express BioTAP-tagged MSL3 were harvested for scale-down experiments. From the sonicated cross-linked chromatin, aliquots of decreasing volume were used for affinity pulldown of MSL3. Ten 15-cm plates of 293-TREx cells were incubated with 1 μg/mL doxycycline overnight to induce expression of BioTAP-tagged BRD4 (short form) or CBX4. See SI Appendix for detailed steps.

Following pulldown, proteins were digested on bead with trypsin. Peptides were desalted by in-laboratory constructed Empore C18-STAGE tips (3M). Raw mass spectrometric data were converted to MGF file format (35). Converted data were processed with SearchGUI and PeptideShaker by searching with X!Tandem against the Drosophila melanogaster or human proteome downloaded from UniProt (36, 37). Methionine oxidation was a variable modification, with precursor mass tolerance of 10–20 ppm, fragment ion tolerance of 0.5 Da, and two maximum missed trypsin cleavages. Mass spectrometric files are available upon request.

HILIC Protocol for Input and IgG Elution Samples.

The following protocol is modified from (15). See SI Appendix for detailed steps, where the specified amounts of protein are typically recovered at sufficient quantities for LC-MS analysis of both input and IgG elutions. Agencourt AMPure-XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter) were equilibrated with water at room temperature. Beads were resuspended in 70% ethanol before addition of samples. Fifty micrograms of IgG elution, as approximated by Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad), were diluted in water and acidified with acetic acid. Samples were further diluted with equal volume of acetonitrile. Beads were added, and the suspension was rotated at room temperature for 30 min. Beads were washed with 70% (vol/vol) ethanol three times and 100% acetonitrile one time. Beads were resuspended in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (AMBIC) with 2 μg of sequencing grade trypsin overnight at 37 °C (Promega). Supernatant was acidified with acetic acid and desalted with C18-STAGE tips for LC-MS.

On-Bead Propionic Anhydride Derivatization.

See SI Appendix for detailed steps. Approximately 108 293-TREx and 109 or S2 cells, respectively, expressing BioTAP-tagged baits were used for histone MS analysis. BioTAP-tagged complexes bound to streptavidin-agarose were washed with AMBIC. Instead of incubating with trypsin, a 3:1 isopropanol:propionic anhydride mixture was first added to beads followed by ammonium hydroxide to restore pH to ∼7–9. The beads were incubated in a shaking heat block set at 37 °C for 15 min. Beads were then washed with AMBIC twice before a second anhydride treatment. Washed beads were incubated with trypsin in AMBIC overnight at 37 °C. The supernatant was then derivatized with propionic anhydride as described (17). Propionylated peptides were desalted with C18-STAGE tips for LC-MS. Genomic histones were prepared by lysing cells with RIPA buffer followed by high salt and sulfuric acid extraction. Histones were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid, washed with acetone, and prepared by propionic anhydride as described (17). To induce histone acetylation, 5 mM sodium butyrate was added to S2 tissue culture medium for overnight incubation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the M.I.K. laboratory for helpful discussion, Ross Tomaino for liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry, Erica Walsh and Chris French for the BRD4 cell line, and Qikai Xu for the CBX4 gene. B.M.Z. acknowledges funding from the Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund. M.I.K. acknowledges funding from National Institutes of Health Grants GM45744 and GM101958.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1522750113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kornberg RD, Lorch Y. Twenty-five years of the nucleosome, fundamental particle of the eukaryote chromosome. Cell. 1999;98(3):285–294. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81958-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pazin MJ, Kadonaga JT. What’s up and down with histone deacetylation and transcription? Cell. 1997;89(3):325–328. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80211-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293(5532):1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brookes E, Shi Y. Diverse epigenetic mechanisms of human disease. Annu Rev Genet. 2014;48:237–268. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-120213-092518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alekseyenko AA, et al. Heterochromatin-associated interactions of Drosophila HP1a with dADD1, HIPP1, and repetitive RNAs. Genes Dev. 2014;28(13):1445–1460. doi: 10.1101/gad.241950.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alekseyenko AA, Gorchakov AA, Kharchenko PV, Kuroda MI. Reciprocal interactions of human C10orf12 and C17orf96 with PRC2 revealed by BioTAP-XL cross-linking and affinity purification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(7):2488–2493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400648111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang H, et al. Sex comb on midleg (Scm) is a functional link between PcG-repressive complexes in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2015;29(11):1136–1150. doi: 10.1101/gad.260562.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huttlin EL, et al. The BioPlex network: A systematic exploration of the human interactome. Cell. 2015;162(2):425–440. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alekseyenko AA, et al. BioTAP-XL: Cross-linking/tandem affinity purification to study DNA targets, RNA, and protein components of chromatin-associated complexes. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2015;109:21.30.1–21.30.32. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb2130s109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zybailov B, et al. Statistical analysis of membrane proteome expression changes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Proteome Res. 2006;5(9):2339–2347. doi: 10.1021/pr060161n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morales V, et al. Functional integration of the histone acetyltransferase MOF into the dosage compensation complex. EMBO J. 2004;23(11):2258–2268. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith ER, et al. The drosophila MSL complex acetylates histone H4 at lysine 16, a chromatin modification linked to dosage compensation. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(1):312–318. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.312-318.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindehell H, Kim M, Larsson J. Proximity ligation assays of protein and RNA interactions in the male-specific lethal complex on Drosophila melanogaster polytene chromosomes. Chromosoma. 2015;124(3):385–395. doi: 10.1007/s00412-015-0509-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhai B, Villén J, Beausoleil SA, Mintseris J, Gygi SP. Phosphoproteome analysis of Drosophila melanogaster embryos. J Proteome Res. 2008;7(4):1675–1682. doi: 10.1021/pr700696a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes CS, et al. Ultrasensitive proteome analysis using paramagnetic bead technology. Mol Syst Biol. 2014;10:757. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alpert AJ. Hydrophilic-interaction chromatography for the separation of peptides, nucleic acids and other polar compounds. J Chromatogr A. 1990;499:177–196. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)96972-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leroy G, et al. A quantitative atlas of histone modification signatures from human cancer cells. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2013;6(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-6-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schotta G, et al. A chromatin-wide transition to H4K20 monomethylation impairs genome integrity and programmed DNA rearrangements in the mouse. Genes Dev. 2008;22(15):2048–2061. doi: 10.1101/gad.476008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan M, et al. Identification of 67 histone marks and histone lysine crotonylation as a new type of histone modification. Cell. 2011;146(6):1016–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ku M, et al. H2A.Z landscapes and dual modifications in pluripotent and multipotent stem cells underlie complex genome regulatory functions. Genome Biol. 2012;13(10):R85. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-10-r85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan W, et al. H3K36 methylation antagonizes PRC2-mediated H3K27 methylation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(10):7983–7989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.194027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng Y, Thomas PM, Kelleher NL. Measurement of acetylation turnover at distinct lysines in human histones identifies long-lived acetylation sites. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2203. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plazas-Mayorca MD, et al. One-pot shotgun quantitative mass spectrometry characterization of histones. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(11):5367–5374. doi: 10.1021/pr900777e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LeRoy G, et al. Proteogenomic characterization and mapping of nucleosomes decoded by Brd and HP1 proteins. Genome Biol. 2012;13(8):R68. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-8-r68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang CI, et al. Chromatin proteins captured by ChIP-mass spectrometry are linked to dosage compensation in Drosophila. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20(2):202–209. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon JA, Kingston RE. Mechanisms of polycomb gene silencing: Knowns and unknowns. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(10):697–708. doi: 10.1038/nrm2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dey A, Chitsaz F, Abbasi A, Misteli T, Ozato K. The double bromodomain protein Brd4 binds to acetylated chromatin during interphase and mitosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(15):8758–8763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1433065100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson V. Studies on histone organization in the nucleosome using formaldehyde as a reversible cross-linking agent. Cell. 1978;15(3):945–954. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solomon MJ, Larsen PL, Varshavsky A. Mapping protein-DNA interactions in vivo with formaldehyde: Evidence that histone H4 is retained on a highly transcribed gene. Cell. 1988;53(6):937–947. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)90469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu CH, et al. Sequence-specific capture of protein-DNA complexes for mass spectrometric protein identification. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e26217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aoki T, et al. Bi-functional cross-linking reagents efficiently capture protein-DNA complexes in Drosophila embryos. Fly (Austin) 2014;8(1):43–51. doi: 10.4161/fly.26805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dalvai M, et al. A scalable genome-editing-based approach for mapping multiprotein complexes in human cells. Cell Reports. 2015;13(3):621–633. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voigt P, et al. Asymmetrically modified nucleosomes. Cell. 2012;151(1):181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu F, Wu C, Sweedler JV, Goshe MB. An enhanced protein crosslink identification strategy using CID-cleavable chemical crosslinkers and LC/MS(n) analysis. Proteomics. 2012;12(3):401–405. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chambers MC, et al. A cross-platform toolkit for mass spectrometry and proteomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(10):918–920. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaudel M, Barsnes H, Berven FS, Sickmann A, Martens L. SearchGUI: An open-source graphical user interface for simultaneous OMSSA and X!Tandem searches. Proteomics. 2011;11(5):996–999. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaudel M, et al. PeptideShaker enables reanalysis of MS-derived proteomics data sets. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(1):22–24. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.