Abstract

Objective:

To compare natalizumab and fingolimod on both clinical and MRI outcomes in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) from 27 multiple sclerosis centers participating in the French follow-up cohort Observatoire of Multiple Sclerosis.

Methods:

Patients with RRMS included in the study were aged from 18 to 65 years with an Expanded Disability Status Scale score of 0–5.5 and an available brain MRI performed within the year before treatment initiation. The data were collected for 326 patients treated with natalizumab and 303 with fingolimod. The statistical analysis was performed using 2 different methods: logistic regression and propensity scores (inverse probability treatment weighting).

Results:

The confounder-adjusted proportion of patients with at least one relapse within the first and second year of treatment was lower in natalizumab-treated patients compared to the fingolimod group (21.1% vs 30.4% at first year, p = 0.0092; and 30.9% vs 41.7% at second year, p = 0.0059) and supported the trend observed in nonadjusted analysis (21.2% vs 27.1% at 1 year, p = 0.0775). Such statistically significant associations were also observed for gadolinium (Gd)-enhancing lesions and new T2 lesions at both 1 year (Gd-enhancing lesions: 9.3% vs 29.8%, p < 0.0001; new T2 lesions: 10.6% vs 29.6%, p < 0.0001) and 2 years (Gd-enhancing lesions: 9.1% vs 22.1%, p = 0.0025; new T2 lesions: 16.9% vs 34.1%, p = 0.0010) post treatment initiation.

Conclusion:

Taken together, these results suggest the superiority of natalizumab over fingolimod to prevent relapses and new T2 and Gd-enhancing lesions at 1 and 2 years.

Classification of evidence:

This study provides Class IV evidence that for patients with RRMS, natalizumab decreases the proportion of patients with at least one relapse within the first year of treatment compared to fingolimod.

In European countries, natalizumab (Tysabri; Biogen, Cambridge, MA), a monoclonal antibody targeting VLA4, and fingolimod (Gilenya; Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Basel, Switzerland), a sphingosine-1 receptor antagonist,1 share the same indication as second-line therapies in highly active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) or as first-line therapy for aggressive and rapidly evolving disease.

Pivotal trials have shown at 2 years the higher benefits of fingolimod and natalizumab over placebo on both clinical and MRI disease activity.2–6 In terms of safety, both natalizumab and fingolimod are generally well-tolerated.2–6 However, natalizumab could be associated with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a rare but serious adverse event caused by the JC virus (JCV),7,8 making its use difficult in predisposed patients. Besides, fingolimod is rarely associated with serious adverse events such as opportunistic infection, transient bradycardia occurring at the treatment initiation, and basal cell carcinoma.2–4

Considering the benefit/risk ratio of these 2 treatments, it appears useful to compare their efficacy in order to guide the treatment choice for a given patient. Recent observational studies have reported inconsistent results on clinical multiple sclerosis (MS) activity at 1 year (annualized relapse rate, time to first relapse),9–13 but none has compared clinical efficacy or MRI disease activity at 2 years in a large population of patients.

We conducted analyses of both clinical and MRI outcomes at 1 and 2 years from treatment initiation in a French national cohort that includes 629 patients with RRMS treated with either fingolimod or natalizumab to provide additional information on their relative efficacy.

METHODS

The Observatoire of Multiple Sclerosis (OFSEP) cohort.

We performed a retrospective analysis of data prospectively collected from 27 French university hospitals involved in the French OFSEP14 using the European database for multiple sclerosis software (EDMUS).15 Individual case reports included identification and demographic data, medical history, biological, electrophysiologic, and MRI data and treatments, as well as key episodes in MS course (date of relapses, date of secondary progression, dates of disability progression). Data were checked for consistency by the EDMUS software using automatic controls. For the CEFNA study, data were collected from the OFSEP database through an extraction of EDMUS on July 11, 2014.

Patients.

The following inclusion criteria were defined: patients with RRMS aged from 18 to 65 years, with an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score ranging between 0 and 5.5, who initiated either natalizumab or fingolimod between January 1, 2011, and January 1, 2013 (to avoid a period bias as natalizumab and fingolimod were available in France since May 2007 and December 2011, respectively), and with an available MRI scan and EDSS assessment within the year before treatment initiation. Patients with prior second-line treatment were not included (natalizumab, fingolimod, cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone, alemtuzumab, or rituximab).

Clinical baseline characteristics included demographic information, disease duration until fingolimod or natalizumab initiation, use of previous disease-modifying treatment, EDSS level, number of relapses in the preceding year to fingolimod or natalizumab initiation, and the presence of gadolinium (Gd)–enhancing lesions on baseline MRI scan. These baseline variables were considered as possible confounding factors for the further statistical analyses.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The study was conducted in accordance with the French law relative to clinical noninterventional research. According to the French law on Bioethics (July 29, 1994; August 6, 2004; and July 7, 2011, Public Health Code), the patients' written informed consent was collected. Moreover, data confidentiality was ensured in accordance with the recommendations of the French commission for data protection (Commission Nationale Informatique et Liberté, CNIL decision DR-2014-558).

Endpoints.

The primary research question was the proportion of patients with at least one relapse within the first year of treatment. A relapse was defined by any new or recurrent exacerbation of neurologic symptoms without fever that lasted for at least 24 hours. Secondary endpoints were the proportion of patients with at least one relapse at 2 years of treatment, the proportion of patients with a progression of disability defined by any increase in EDSS score at 12 and 24 months (more or less 3 months) compared to baseline, the proportion of patients with at least one Gd-enhancing lesion, and the proportion of patients with at least one new T2 lesion on MRI scans performed at 12 and 24 months (more or less 3 months) compared to baseline MRI scan.

The results provide Class IV evidence in favor of natalizumab to prevent relapse within the first year of treatment and are supported by clinical data at 2 years and by MRI data.

Statistical analyses.

The analyses were performed regarding the initial treatment without considering the treatment's modifications. The fingolimod-treated and natalizumab-treated patients were compared using t tests or Wilcoxon tests for continuous variables and χ2 statistics for categorical variables.

In order to compare the 4 endpoints at 1 year post initiation, the following possible confounders were taken into consideration: sex, number of relapses during the year prior to fingolimod or natalizumab treatment onset, presence of Gd-enhancing lesion at baseline MRI, EDSS baseline score, and hospital. This list was determined according to medical arguments without statistical selection.

We considered 2 alternative statistical methods. (1) The multivariate logistic regression allowed us to obtain confounder-adjusted odds ratios (ORs). The principle is to model the probability of the event according to the treatment (fingolimod vs natalizumab) and the other covariates. To interpret the treatment effect, the covariates' levels have to be fixed and therefore the treatment effect cannot be due to covariate imbalance between the 2 treatments. Such a modeling strategy represents the most popular tool to obtain confounder-adjusted results. (2) The propensity score method based on inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) allowed us to estimate confounder-adjusted absolute risks in both fingolimod- and natalizumab-treated groups. The basic idea is to model how the probability of receiving fingolimod and natalizumab depends on the confounders. More precisely, for each patient, the weight was the ratio between the mean probability to receive her or his treatment and the individual predicted probability to receive this treatment according to the 4 covariates previously listed. The individual probabilities were the predicted value obtained by using logistic regression with hospital as random effect and treatment group as outcome.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software.16

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of fingolimod- and natalizumab-treated patients: The confounding indication of natalizumab in patients with active disease.

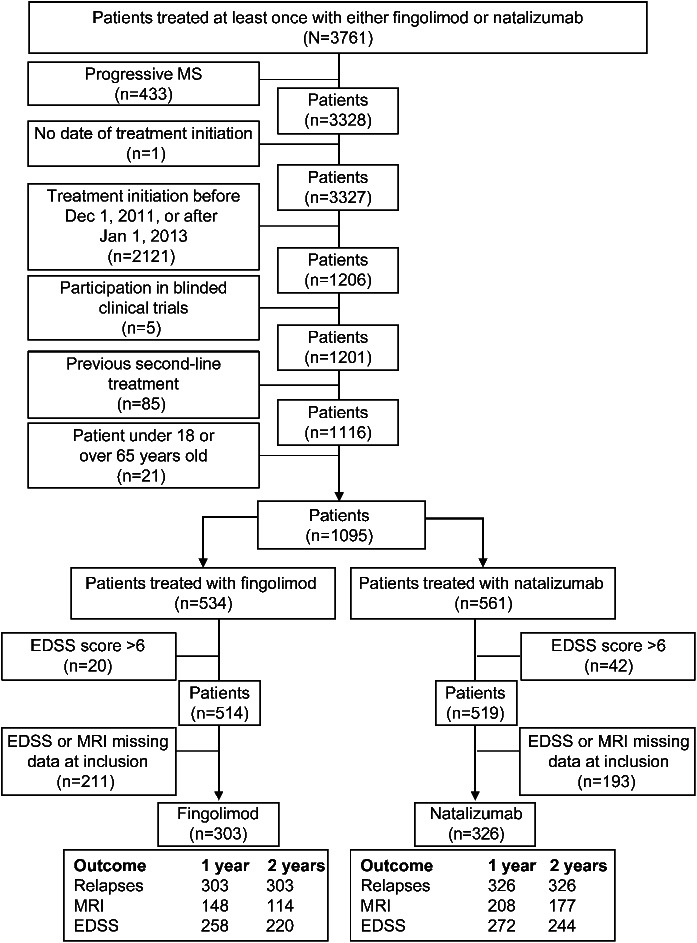

From the 40,965 patients of the OFSEP database, a total of 3,761 patients followed in the 27 university hospitals participating in this study had at least one prescription for either fingolimod or natalizumab. Among these patients, 303 treated with fingolimod and 326 with natalizumab met the inclusion criteria (figure 1).

Figure 1. Patient selection diagram.

EDSS = Expanded Disability Status Scale; MS = multiple sclerosis.

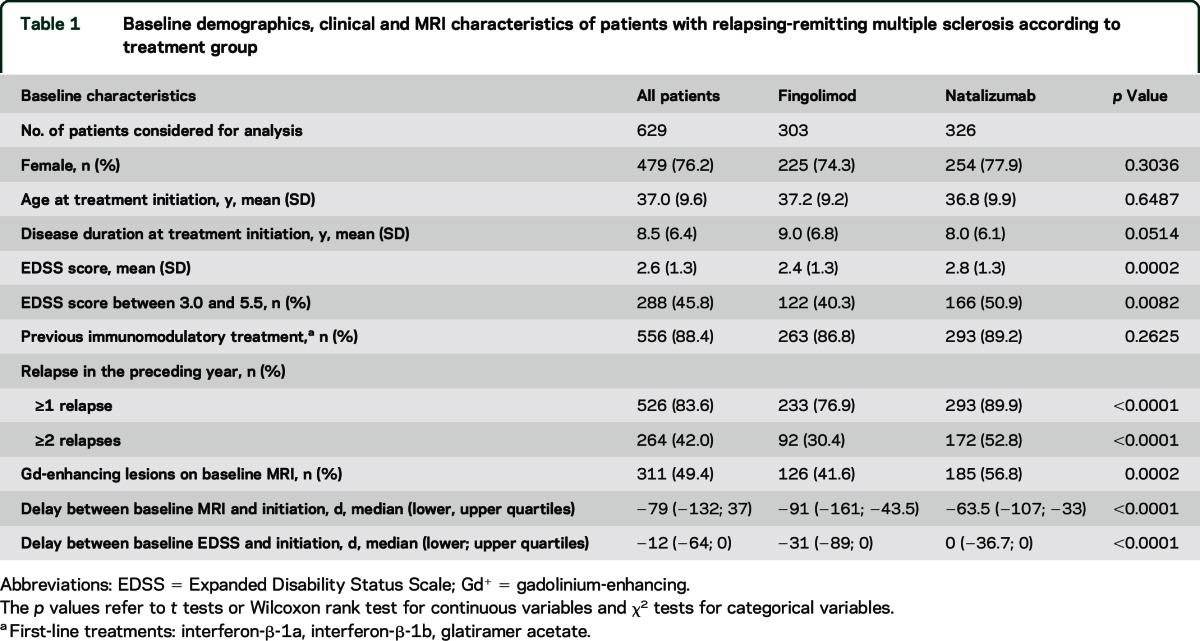

Baseline demographics and clinical and MRI characteristics of the 629 patients with RRMS included in the study according to treatment group are presented in table 1. Of the 629 patients, a total of 539 patients (83.3% of the fingolimod-treated patients and 87.4% of the natalizumab-treated patients) and 458 patients (75.9% of the fingolimod-treated patients and 69.9% of the natalizumab-treated patients) had received the treatment, respectively, for at least 1 and 2 years. There was a significantly shorter median time from baseline MRI to natalizumab or fingolimod initiation. The median time between baseline EDSS assessment and the treatment initiation was also shorter in natalizumab- than in fingolimod-treated patients. Both treatments were mostly initiated in patients previously treated with at least one first-line DMT. The proportion of treatment-naive patients was close between the 2 groups (10.1% for natalizumab vs 13.2% for fingolimod). Patients with natalizumab had more clinically active MS than patients with fingolimod, with a tendency towards a shorter disease duration (8.0 ± 6.1 years vs 9.0 ± 6.8 years, p = 0.0514) and higher EDSS score (2.8 ± 1.3 vs 2.4 ± 1.3, p = 0.0002). In addition, there were more natalizumab- than fingolimod-treated patients with at least 1 or 2 relapses in the preceding year of treatment (p < 0.0001), and at least one active lesion on baseline MRI scans (p = 0.0002).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics, clinical and MRI characteristics of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis according to treatment group

Such confounding by indication required adjustments for the subsequent comparisons of the evolution of patients between the 2 treatment groups.

Intraindividual evolution of patients during the 2 first years post initiation in each group: Fingolimod and natalizumab were both efficient on the disease activity.

Analyses on clinical and MRI endpoints were performed on different sample sizes due to missing data. The sample sizes were 629 patients for relapse endpoint at both 1 and 2 years (fingolimod: 303 vs natalizumab: 326), 351 patients (fingolimod: 143 vs natalizumab: 208) at 1 year, and 291 (fingolimod: 114 vs natalizumab: 177) at 2 years for both MRI endpoints and 530 patients (fingolimod: 258 vs natalizumab: 272) at 1 year and 464 (fingolimod: 220 vs natalizumab: 244) at 2 years for EDSS endpoint, as indicated in figure 1. Fingolimod-treated patients and natalizumab-treated patients underwent 1-year MRI scan with a median of 378 days (quartiles 310 to 470.5) and 346 days (quartiles 323 to 398) post initiation, respectively (not significant [NS]). EDSS score was performed with a median of 362 days (quartiles 315 to 401.7) post initiation in fingolimod-treated patients and 357 days (quartiles 329 to 384.2) post initiation in natalizumab-treated patients (NS).

The initiation of both treatments allowed a better control of clinical and MRI activities of MS at 1 year. Indeed, 76.9% of fingolimod-treated patients had had at least one relapse in the year preceding the treatment initiation, while only 27.1% of these patients had a relapse after 1 year of treatment (p < 0.0001) and 37.9% after 2 years (p < 0.0001). In the same way, 89.9% of natalizumab-treated patients had at least one relapse in the year preceding treatment initiation compared to 21.2% in the year posttreatment (p < 0.0001) and 31% in the second year (p < 0.0001). Similar results were obtained for the presence of Gd-enhancing lesions. In the fingolimod-treated cohort, 42% of the patients had at least one Gd-enhancing lesion on the baseline brain MRI compared to 21.0% at 1 year (p = 0.0002). This effect was maintained over 2 years (43.9% vs 19.3%, p = 0.0001). In the natalizumab-treated cohort, 57.7% of the patients had at least one Gd-enhancing lesion at baseline compared to 8.2% at 1 year (p < 0.0001) and this effect was maintained over 2 years (55.1% vs 8.6%, p < 0.0001). Concerning EDSS scores, a significant decrease after 1 year of treatment was observed in both groups: from 2.4 to 2.2 for the fingolimod-treated patients (p = 0.0228) and from 2.8 to 2.6 for natalizumab-treated patients (p = 0.0118). This difference was not maintained at 2 years in both groups of patients (from 2.4 to 2.2 for fingolimod, p = 0.1843, and from 2.8 to 2.6 for natalizumab, p = 0.1451).

Comparisons of endpoints at both 1 and 2 years between both groups: Fingolimod is less efficient than natalizumab.

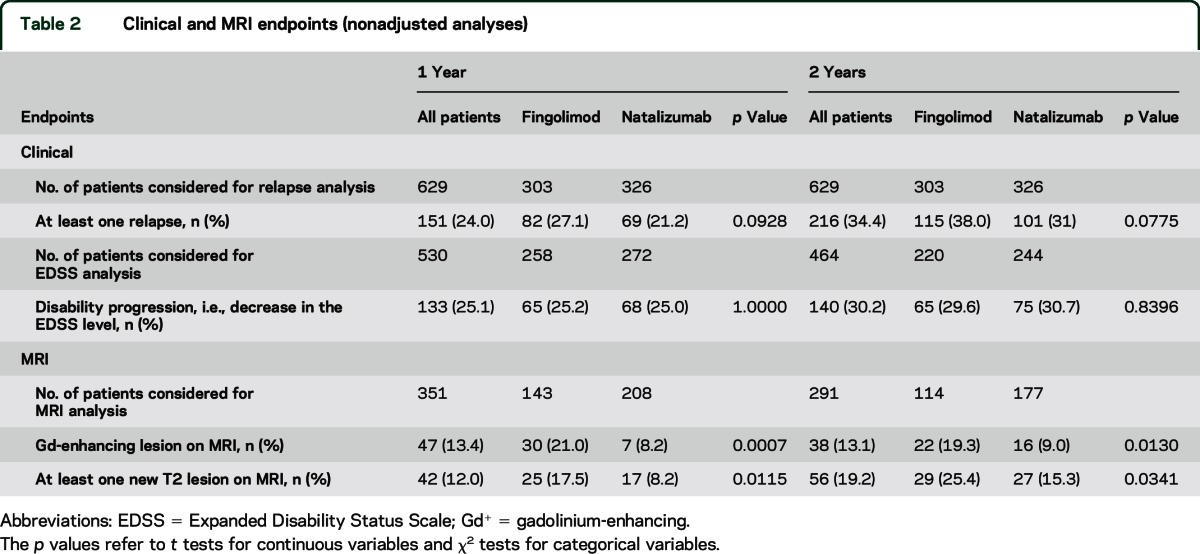

Table 2 presents raw comparisons at 1 and 2 years between the 2 groups. They reveal a trend toward higher disease activity with increased percentage of relapse in fingolimod-treated patients as compared to patients treated with natalizumab (p = 0.0928) at 1 year. This tendency was maintained over 2 years (p = 0.0775). The MRI outcomes supported this trend at both 1 and 2 years. The proportion of patients with at least one Gd-enhancing lesion and new T2 lesion was significantly increased at both 1 (p = 0.0007 and p = 0.0115) and 2 (p = 0.0130 and p = 0.0341) years in patients treated with fingolimod compared to natalizumab.

Table 2.

Clinical and MRI endpoints (nonadjusted analyses)

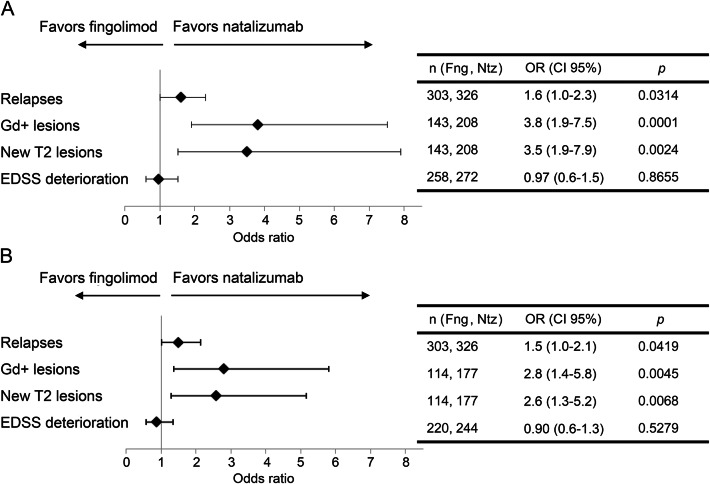

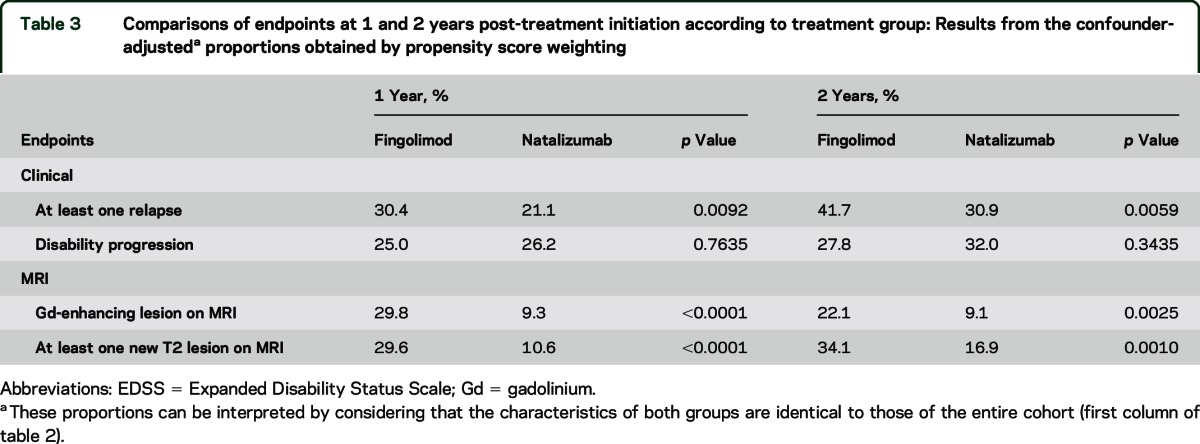

In order to take into consideration the biases due to differences between the 2 groups at treatment initiation, we performed a multivariate logistic regression (figure 2) and computed the confounder-adjusted proportions of events by propensity score weighting at 1 and 2 years post initiation (table 3). Altogether, both methods showed consistent results. Considering that the characteristics of both groups are identical to those of the entire cohort (first column of table 1), we estimated that 30.4% of fingolimod-treated patients would have at least one relapse within the first year of treatment vs 21.1% among natalizumab-treated patients. This significant difference (p = 0.0092) was maintained over 2 years of treatment (41.7% vs 30.9%, p = 0.0059) and was confirmed using multivariate logistic regression at 1 and 2 years (figure 2).

Figure 2. Adjusted multivariate logistic regression on clinical and radiologic disease activities according to treatment group.

Multivariate analyses were represented as Forest plots at (A) 1 and (B) 2 years of treatment. The covariates used for adjustment were sex, number of relapses during the year prior to fingolimod or natalizumab treatment onset, presence of Gd-enhancing lesion at baseline MRI, EDSS baseline score, and university hospital as a random effect. CI = confidence interval; EDSS = Expanded Disability Status Scale; Fng = fingolimod; Gd = gadolinium; Ntz = natalizumab; OR = odds ratio.

Table 3.

Comparisons of endpoints at 1 and 2 years post-treatment initiation according to treatment group: Results from the confounder-adjusteda proportions obtained by propensity score weighting

We also estimated that more patients in the fingolimod group than in the natalizumab group had Gd-enhancing lesions at 1 (p < 0.0001) and 2 years (p = 0.0025) or new T2-lesion at both 1 (p < 0.0001) and 2 years (p = 0.0010) (table 3). The significant differences between these confounder-adjusted percentages of lesions at 1 and 2 years were also confirmed by multivariate logistic regressions (figure 2). The median time between the initiation of treatment and the first relapse was comparable in the fingolimod cohort (138.5 days [quartiles 59.5 to 233]) and in the natalizumab cohort (135 days [quartiles 83 to 239]) (NS, nonadjusted comparison). Whatever the method used, no significant difference was observed in terms of EDSS score progression between the 2 groups of patients at 1 and 2 years.

These comparisons may suffer some limitations due to missing data, particularly concerning MRI parameters. Indeed, brain MRIs are not systematically performed before starting fingolimod or natalizumab and, when available, MRI data are not systematically registered. To assess this possible bias, we compared the 184 patients (100 in the fingolimod group and 84 in the natalizumab group) who did not get brain MRI before treatment initiation and thus were not included in the study to those for whom MRI was available (629 patients). As shown in table e-1A (on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org), patients without MRI were older (p = 0.0413) and had a longer disease duration (p = 0.0138). Moreover, 66.3% of these patients had a relapse in the year before compared to 83.6% of included patients (p < 0.0001). However, this bias seemed to affect both cohorts similarly (tables e-1B and e-1C). This result suggests that only the patients with more clinically active disease had a brain MRI before starting their treatment.

In the same way, some MRI data are also missing after 1 year of follow-up (160 patients for fingolimod and 118 for natalizumab). Again, we observed a significantly lower percentage of patients with a relapse at 1 year post-treatment for patients with missing MRI at 1 year compared to others (table e-2A). This bias seemed similar between both groups (tables e-2B and e-2C).

DISCUSSION

Observational studies can offer an attractive alternative when randomized clinical trials (RCTs) are not available. In the present observational study, fingolimod seems less efficient than natalizumab on disease activity as assessed on relapse occurrence, new gadolinium-enhancing lesions, and new T2 lesions on brain MRI, after 1 and 2 years of treatment.

RCTs have demonstrated the superiority of natalizumab and fingolimod over placebo to reduce MS activity.2–6 Our results regarding the proportion of natalizumab-treated patients free from relapse or Gd-enhancing lesions were approaching those reported in the AFFIRM study at 1 and 2 years.5,6 On the contrary, fingolimod treatment effect on MS activity seems lower in our study than in FREEDOMS at both 1 and 2 years.2,4 These differences observed with fingolimod could be due to the characteristics of the patients selected in RCTs.

Four recent observational studies have compared fingolimod and natalizumab, but with inconsistent results.9–13 In the more recent study,13 based on the analysis of a multicenter database of patients with more active MS switched to natalizumab or fingolimod treatments, natalizumab seemed to be more effective than fingolimod on clinical parameters. However, in this study, no MRI outcomes were taken into account in the analysis. Similarly to our work, the authors found that more severe disease preceding treatment initiation was associated with a probability to switch to natalizumab. Hence, in this study13 and ours, similar proportions of relapse-free patients with natalizumab and fingolimod at 1 (81% and 63%) and 2 years (77% vs 52%) were reported. However, on the contrary we were unable to detect any difference in terms of EDSS at 1 and 2 years between the 2 treatments but our study was not specifically designed for this outcome as a primary endpoint. In order to take into consideration unbalanced characteristics of the patients at baseline, we used 2 different well-established statistical methods. First, a multivariate logistic regression, the most used method in the literature to assess a treatment effect for binary endpoints, was used. However, its main concern is the loss of information due to summing up of the results in a single OR. This ratio represents a relative effect of treatment and is difficult to interpret for physicians. Reporting the absolute risks, that can be achieved using the second statistical method used, IPTW, is therefore important for a relevant interpretation.17 Moreover adjusted propensity score on identified confounding factors reduces biases inherent to observational design and more particularly allocation bias. The results of both methods were concordant. However, one cannot exclude the presence of some confounding factors of unknown origin, in the contrary of RCTs which allow the baseline characteristics of 2 groups to be well-balanced. Because the main source of bias in such nonrandomized studies is the missing of confounders, one can compare the list we used with the covariates taken into consideration in the paper by Kalincik et al.13 Two additional parameters were considered: evidence of on-treatment MS activity (relapse, progression of disability, or both) and prior/baseline disease-modifying therapies. In contrast, in our study the presence of Gd-enhancing lesions on baseline MRI scan was considered.

Our observational study suffers some limitations. First, we chose MRI data as secondary outcomes but there was no central read-out, no central quality control, and no standard acquisition protocol for MRI data. Second, differences are also observed when comparing patients with MRI missing data (not included) and patients without (included). As expected, patients with missing data had less active disease than the others, for whom the disease monitoring was probably more appropriate. Another bias is the observational nature of the study, reflecting clinical practice with data representative of the MS population. The choice of the treatment not only depends on the efficacy of the molecule but also various factors including JCV testing and individual PML risk, the necessity for recurrent hospitalizations, or childbearing potential. Considering these weaknesses, interpretation of the results should be made with caution until RCTs are available to compare the 2 molecules.

Nevertheless, our observational study provides Class IV evidence18 for the superiority of natalizumab over fingolimod to prevent relapse at 1 year. Regarding the absence of RCTs and the heterogeneity of the literature, these results may provide additional information that may help physicians choose second-line treatment for patients with RRMS.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- EDSS

Expanded Disability Status Scale

- Gd

gadolinium

- IPTW

inverse probability of treatment weighting

- JCV

JC virus

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- NS

not significant

- OFSEP

Observatoire of Multiple Sclerosis

- OR

odds ratio

- PML

progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

- RRMS

relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

Contributor Information

Collaborators: CFSEP and OFSEP groups, O. Anne, B. Audouin, E. Berger, D. Brassat, B. Brochet, B. Bourre, P. Cabre, J.P. Camdessanché, O. Casez, P. Clavelou, N. Collongues, M. Coustans, A. Créange, M. Debouverie, G. Defer, N. Derache, J. de Seze, D. Dive, A. Fromont, R. Guider, J. Grimaud, O. Heinzlef, A. Kiatkoswki, P. Labauge, D. Laplaud, C. Lebrun, E. Le Page, R. Marignier, T. Moreau, J.C. Ouallet, C. Papeix, J. Pelletier, S. Pittion, L. Rumbach, M. Schluep, P. Seeldrayers, I.S. Sennou, B. Stankoff, F. Thaite, A. Tourbah, E. Thouvenot, P. Vermersch, S. Vukusic, S. Wiertlewski, H. Zephir, Sandra Vukusic, Michel Clanet, Bertrand Fontaine, Bruno Stankoff, Thibault Moreau, Bruno Brochet, Jean Pelletier, Jérôme de Seze, François Cotton, Vincent Dousset, David Laplaud, Jérôme de Seze, Sandra Vukusic, Romain Marignier, Françoise Durand-Dubief, Marc Debouverie, Francis Guillemin, Sophie Pittion-Vouyovitch, Gilles Edan, Emmanuelle Leray, Emmanuelle le Page, Michel Clanet, David Brassat, Bruno Brochet, Jean-Christophe Ouallet, Catherine Lubetzki, Bertrand Fontaine, Caroline Papeix, Bruno Stankoff, Alain Creange, Yann Mikaeloff, Kumaran Deiva, Marie Theaudin, Olivier Gout, Caroline Bensa, Olivier Heinzlef, Nicolas Collongues, Patrick Vermersch, Hélène Zephir, Olivier Outteryck, Patrick Hautecoeur, Arnaud Kwiatkowski, Christine Lebrun-Frenay, Mikael Cohen, Thibault Moreau, Agnès Fromont, Pierre Clavelou, Sandrine Wiertlewski, Jean Pelletier, Bertrand Audoin, Audrey Rico-Lamy, Gilles Defer, Nathalie Derache, Eric Berger, Giovanni Castelnovo, Eric Thouvenot, Philippe Cabre, Pierre Labauge, William Camu, Bertrand Bourre, Jean-Philippe CAMDESSANCHE, Laurent Magy, Alexis Montcuquet, Abdelatif Al-Khedr, Ayman Tourbah, Olivier Casez, Anne-Marie Guennnoc, Jonathan Ciron, S. Pittion, R. Marignier, N. Derache, F. Durand-Dubief, N. Collongues, M. Fleury, M. Clanet, L. Michel, J.C. Ouallet, A. Ruet, B. Audouin, A. Rico, H. Zephir, E. Le Page, V. Deburghgraeve, M. Cohen, G. Castelnovo, C. Lubetzki, A. Fromont, C. Bensa, and J.M. Vallat

AUTHOR AFFILIATIONS

From INSERM (L.B., C.R., N.J., D.A.L.), CIC 0004, Nantes; EA 4275 Biostatistics (C.R., Y.F.), Clinical Research and Subjective Measures in Health Sciences, Nantes University; Service de Pharmacologie Clinique (C.R.), CIC Inserm 1414, CHU de Rennes, Université de Rennes 1; Observatoire Français de la Sclérose en Plaques (R.C., S.V.), Université de Lyon, Hospices Civils de Lyon; Service de Neurologie (M.D.), CHU de Nancy; Service de Neurologie (S.V.), CHU de Lyon; Service de Neurologie (J.D.S.), CHU de Strasbourg; Service de Neurologie (D.B.), CHU de Toulouse; CHU Nord Laennec (S.W., D.A.L.), Service de Neurologie, Nantes; Service de Neurologie (B. Brochet), CHU de Bordeaux; Service de Neurologie (J.P.), CHU de Marseille; Service de Neurologie (P.V.), CHU de Lille; Service de Neurologie (G.E.), CHU de Rennes; Service de Neurologie (C.L.-F.), CHU de Nice; Service de Neurologie (P. Clavelou), CHU de Clermont-Ferrand; Service de Neurologie (E.T.), CHU de Nîmes; Service de Neurologie (J.-P.C.), CHU de Saint-Etienne; Service de Neurologie et Faculté de Médecine de Reims (A.T.), CHU de Reims, URCA; Service de Neurologie (B.S.), CHU Saint-Antoine; Service de Neurologie (A.A.K.), CHU d'Amiens; Service de Neurologie (P. Cabre), CHU de Fort de France; Service de Neurologie (C.P.), CHU de Paris Salpêtrière; Service de Neurologie (E.B.), CHU de Besançon; Service de Neurologie (O.H.), CHU de Poissy; Service de Neurologie (T.D.), CHU de Saint-Denis; Service de Neurologie (T.M.), CHU de Dijon; Service de Neurologie (O.G.), Fondation Rothschild; Service de Neurologie (B. Bourre), CHU de Rouen; Service de Neurologie (A.C.), CHU de Créteil; Service de Neurologie (P.L.), CHU de Montpellier; Service de Neurologie (L.M.), CHU de Limoges; Service de Neurologie (G.D.), CHU de Caen; and INSERM UMR U1064 (D.A.L.), Nantes, France.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Laetitia Barbin: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, study supervision. Chloe Rousseau: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, statistical analysis. Natacha Jousset: study concept or design, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Romain Casey: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, study supervision. Marc Debouverie: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Sandra Vukusic: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data, study supervision. Jerome de Seze: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. David Brassat: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data, study supervision. Sandrine Wiertlewski: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Bruno Brochet: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Jean Pelletier: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Patrick Vermersch: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Gilles Edan: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data, study supervision. Christine Lebrun-Frenay: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Pierre Clavelou: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Eric Thouvenot: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Jean-Philippe Camdessanché: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Ayman Tourbah: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Bruno Stankoff: study concept or design, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, contribution of vital reagents/tools/patients, acquisition of data. Abdullatif Al Khedr: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Philippe Cabre: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Caroline Papeix: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Eric Berger: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Olivier Heinzlef: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Thomas Debroucker: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval. Thibault Moreau: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, contribution of vital reagents/tools/patients, acquisition of data. Olivier Gout: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval. Bertrand Bourre: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Alain Créange: study concept or design, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, contribution of vital reagents/tools/patients. Pierre Labauge: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval. Laurent Magy: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Gilles Defer: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval. Yohann Foucher: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, statistical analysis. David A Laplaud: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data, study supervision.

STUDY FUNDING

This work has been performed with the help of the French Observatoire of Multiple Sclerosis (OFSEP) which is supported by a grant provided by the French State and handled by the “AgenceNationale de la Recherche,” within the framework of the “Investments for the Future” program, under the reference ANR-10-COHO-002.

DISCLOSURE

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brinkmann V, Davis MD, Heise CE, et al. The immune modulator FTY720 targets sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors. J Biol Chem 2002;277:21453–21457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kappos L, Radue EW, O'Connor P, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:387–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen JA, Barkhof F, Comi G, et al. Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:402–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calabresi PA, Radue EW, Goodin D, et al. Safety and efficacy of fingolimod in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (FREEDOMS II): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:545–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polman CH, O'Connor PW, Havrdova E, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2006;354:899–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller DH, Soon D, Fernando KT, et al. MRI outcomes in a placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab in relapsing MS. Neurology 2007;68:1390–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Tyler KL. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy complicating treatment with natalizumab and interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2005;353:369–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langer-Gould A, Atlas SW, Green AJ, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with natalizumab. N Engl J Med 2005;353:375–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braune S, Lang M, Bergmann A. Second line use of fingolimod is as effective as natalizumab in a German out-patient RRMS-cohort. J Neurol 2013;260:2981–2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carruthers RL, Rotstein DL, Healy BC, et al. An observational comparison of natalizumab vs. fingolimod using JCV serology to determine therapy. Mult Scler 2014;20:1381–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gajofatto A, Bianchi MR, Deotto L, Benedetti MD. Are natalizumab and fingolimod analogous second-line options for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis? A clinical practice observational study. Eur Neurol 2014;72:173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jokubaitis VG, Li V, Kalincik T, et al. Fingolimod after natalizumab and the risk of short-term relapse. Neurology 2014;82:1204–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalincik T, Horakova D, Spelman T, et al. Switch to natalizumab versus fingolimod in active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2015;77:425–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vukusic S. Observatoire de la sclérose en plaques (OFSEP). Available at: http://www.ofsep.org/fr/la-cohorte. Accessed August 20, 2015.

- 15.Confavreux CCD, Hommes OR, McDonald WI, Thompson AJ. EDMUS, a European database for multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992;55:671–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Development Core Team; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haynes R. Clinical Epidemiology: How to Do Clinical Practice Research. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Edwards Brothers; 2006:496. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gross RA, Johnston KC. Levels of evidence: taking neurology to the next level. Neurology 2009;72:8–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.