Fluorogenic substrates incorporating the sequence Asp-Glu-Pro-Asp-Ser were able to quantify caspase-3 activity without notable caspase-7 and cathepsin B cross-reactivity.

Fluorogenic substrates incorporating the sequence Asp-Glu-Pro-Asp-Ser were able to quantify caspase-3 activity without notable caspase-7 and cathepsin B cross-reactivity.

Abstract

11 FRET-based fluorogenic substrates were constructed using the pentapeptide template Asp-Glu-X2-Asp-X1′, and evaluated with caspase-3, caspase-7 and cathepsin B. The sequence Asp-Glu-Pro-Asp-Ser was able to selectively quantify caspase-3 activity in vitro without notable caspase-7 and cathepsin B cross-reactivity, while exhibiting low μM K M values and good catalytic efficiencies (7.0–16.9 μM–1 min–1).

Caspases (cysteine-aspartate proteases) are a family of endopeptidases that play a key role in the controlled initiation, execution, and regulation of apoptosis, and are essential in the development and homeostasis of mammals.1 Their deregulation can lead to a number of human pathologies including autoimmune diseases,2 neurodegenerative disorders3 and cancer.4 Caspases are produced as procaspases and undergo post-translational activation by the ‘caspase cascade’ following apoptotic stimuli and initiation of the extrinsic, intrinsic, or granzyme B apoptotic pathways.5 Inactivation of the apoptotic intrinsic pathway is often regarded as a ‘hallmark of cancer’ as it leads to the uncontrolled proliferation of cells.6 The intrinsic pathway responds to intercellular stress triggers, including oncogene activation and DNA damage, and therefore is often targeted in the treatment of cancer.7 In addition, since caspases are usually directly involved in the early stages of apoptosis, they are attractive targets for molecular imaging, especially executioner caspase-3, which is down regulated in a variety of cancers.8

Current methods of caspase-3 detection include the use of antibodies9 and fluorescent inhibitors.10 In addition, FRET-based fluorogenic substrates, consisting of either small molecule fluorophores11 or fluorescent fusion proteins,12 have been developed, typically applying the substrate sequence Asp-Glu-Val-Asp (DEVD).13 Commercially available substrates, such as Ac-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-AFC (AFC = 7-amino-4-trifluoromethyl-coumarin) and MCA-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-Ala-Pro-Lys-DNP (MCA = 7-methoxycoumarin-4-yl)acetyl, (DNP = dinitrophenyl), have been utilised to analyse caspase-3 activity in cell lysates; however, they are unable to measure active caspase in intact cells for real-time analysis due to their inability cross the cell membrane and poor optical properties. Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-NucView™, which displays fluorescence upon cleavage and subsequent DNA binding, can be used to measure caspase-3 activity in cell-based assays.14 All the above substrates are, however, based on the recognition sequence Asp-Glu-Val-Asp and therefore cross-react especially with caspase-7 and cathepsin B.15 Low expression of proapoptotic caspase-7 is also associated with many cancers, and cathepsin B is often overexpressed in cancerous cells, highlighting the necessity to develop substrates and probes that can detect caspase-3 activation without cross-reactivity with these other enzymes. Recently, caspase-3 selectivity over other caspase isoforms was achieved by incorporation of unnatural amino acids into a pentapeptide recognition sequences to enable imaging of caspase-3 activity in live cells.16 Similarly, substitution of glutamic acid in Asp-Glu-Val-Asp with pentafluorophenylalanine gave 4.5-fold selectivity over caspase-7 in vitro along with good selectivity over isoforms 6, 8, 9 and 10.17

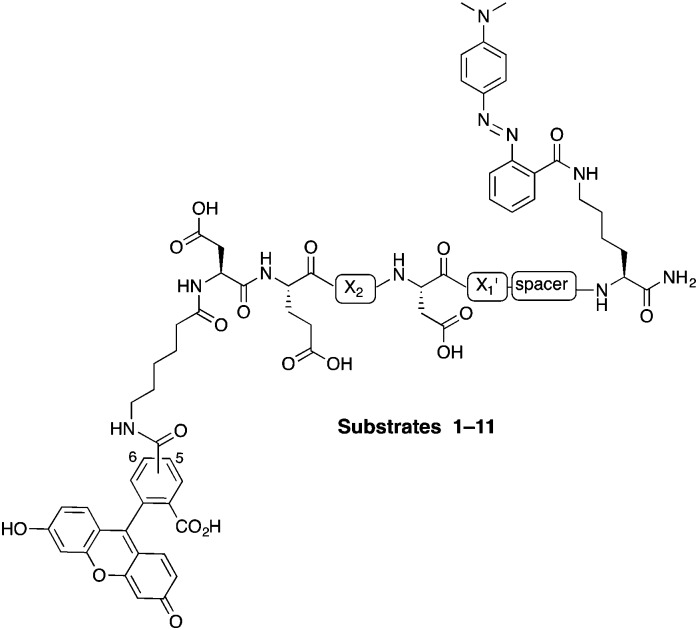

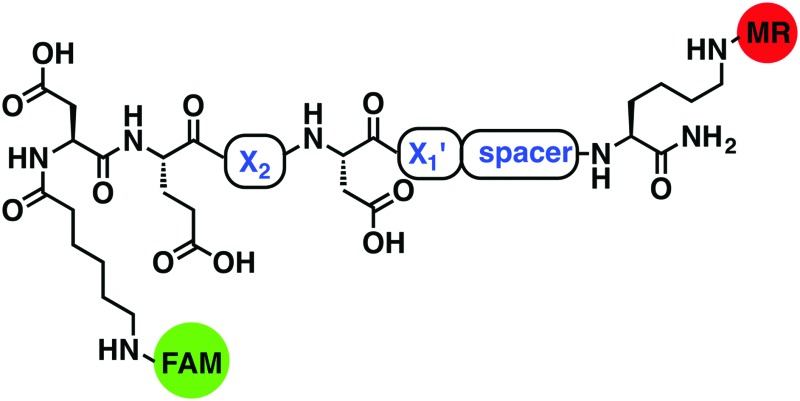

In this study, internally quenched fluorogenic substrates to selectively detect caspase-3 over caspase-7 and cathepsin B were designed and synthesised, and evaluated against human recombinant caspase-3, caspase-7 and cathepsin B. A focused 11-member library of internally quenched substrates was designed incorporating a pentapeptide recognition sequence (X4–X3–X2–X1–X1′). Residue X4 is where the most variability is found within substrates of the caspase family, with preference absolute for aspartic acid for caspase-3 and -7.18 Caspases are not as selective for the X3 position, although glutamic acid is by far the most favoured residue.18 Caspase-3 and -7 both prefer hydrophobic residues at the X2 position, with caspase-7 having far more specific requirements than caspase-3, retaining a higher preference for valine.18a This gives rise to the possibility of improving specificity towards caspase-3 by altering the X2 position.18a,19 Similarly, substitution of valine at the X2 position of Asp-Glu-Val-Asp with proline is known to abolish binding to cathepsin B.20 The X1′ position was incorporated into the recognition sequence to explore if selectivity could be tuned by looking at the residue next to the cleavage/recognition site. At the X1′ position, natural caspase-3 substrates typically show a high preference for small amino acids.21 Therefore, based on these known substrate requirements for caspase-3 and -7 and cathepsin B, a substrate library was designed, incorporating a FRET pair constructed using carboxyfluorescein as the donor (λ Ex/Em 492/517 nm) and methyl red (2-(N,N-dimethyl-4-aminophenyl)azobenzenecarboxylic acid) (λ max ∼ 480 nm) as the acceptor/quencher (see Fig. 1). In the substrates, the X2 position contained either valine or proline, and X1′ glycine, alanine or serine. In addition, a 6-aminohexanoic acid (Ahx) spacer was positioned between the X1′ residue and the methyl red motif in to investigate possible steric hindrance from the quencher.

Fig. 1. Design of the internally quenched substrate library, incorporating a pentapeptide recognition sequence Asp-Glu-X2-Asp-X1′ (caspases cleave between Asp and X1′). The amino-terminus bears a 6-aminohexanoic acid (Ahx) spacer and 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (mixture of isomers) as the donor fluorophore, and the carbon-terminus has a methyl red (quencher) coupled to a lysine side chain. See Table 1 for each individual substrate sequences.

The substrates 1–11 (Fig. 1, Table 1) were synthesised on an Fmoc-Rink-amide linker derivatised aminomethyl polystyrene resin (1% DVB, 100–200 mesh, loading 1.2 mmol g–1) using standard Fmoc solid-phase chemistry with DIC and Oxyma as the coupling combination (ESI,† Schemes S1 and S2). Fmoc-Lys(Dde)-OH was coupled onto the Rink-linker followed by coupling of the Ahx linker (when present) and next five amino acids (Asp-Glu-X2-Asp-X1′). With the amino-terminus Fmoc group still attached, the Dde protecting group was selectively removed with NH2OH·HCl/imidazole, followed by coupling of methyl red (in essence Fmoc-Lys(Dde)-OH is a bi-functional spacer utilising the orthogonal nature of the Fmoc and Dde protecting groups).22 Finally, Ahx spacer and 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein were consecutively coupled. This modular approach allows for the changing of the quencher or conversion of the positions of the quencher and the fluorophore at final stages of the synthesis. After deprotection and cleavage off the resin, the substrates were purified by preparative RP-HPLC and analysed by MALDI-ToF MS.

Table 1. 11-membered FRET-based substrate library FAM-Ahx-Asp-Glu-X2-Asp-X1′-spacer-Lys(MR)-NH2 (see Fig. 1 for structures) a .

| Substrate | X2 | X1′ | Spacer |

| 1 | Val | Gly | — |

| 2 | Pro | Ala | — |

| 3 | Pro | Ser | — |

| 4 | Val | — | Ahx b |

| 5 | Pro | — | Ahx |

| 6 | Pro | Gly | Ahx |

| 7 | Val | Gly | Ahx |

| 8 | Pro | Ala | Ahx |

| 9 | Val | Ala | Ahx |

| 10 | Pro | Ser | Ahx |

| 11 | Val | Ser | Ahx |

aFor the solid-phase synthesis and characterisation of the fluorogenic substrates, see ESI.

bAhx = 6-aminohexanoic acid.

Peptides 1–11 were initially evaluated for their ability to act as substrates for caspase-3 and -7 at 2.5, 5 and 10 μM allowing the effects of the X2 and X1′ substitutions to be assessed. All the substrates had low background fluorescence levels and showed time dependent activation with caspase-3 (ESI,† Fig. S1). Substrates 2 (Asp-Glu-Pro-Asp-Ala) and 3 (Asp-Glu-Pro-Asp-Ser), both of which have proline at the X2 position, showed reduced activation with caspase-3 compared to the other probes; however, this activity was restored by introduction of the Ahx spacer (8 and 10), suggesting that the reduced cleavage of 2 and 3 arose from steric hindrance by the methyl red moiety in combination with the proline residue. In the preliminary screen, no significant preference was observed for glycine, alanine or serine at the X1′ position. Substrate 9 showed a 3 and 5-fold higher increase in fluorescence than Ac-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-AFC (AFC) and MCA-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-Ala-Pro-Lys-DNP (MCA), respectively (ESI,† Fig. S2). In the initial screens, caspase-7 showed significantly lower cleavage of substrates containing proline at X2 position, confirming that selectivity can be achieved by replacing valine in that position (ESI,† Fig. S3 and S4).19c

To evaluate the effectives of the substrates, as well as to further investigate selectivity, the K M and k cat values of 1–11 were determined for caspase-3 and caspase-7 (Table 2). All the substrates exhibited good affinity for caspase-3 (K M values <5 μM) compared to AFC and MCA (K M values 9.8 μM and 13.5 μM, respectively). Substrates bearing a valine at X2 position typically showed lower K M values than the corresponding peptides bearing a X2 proline, with the exception of substrate 10 (sequence Asp-Glu-Pro-Asp-Ser- Ahx, K M 1.8 μM), which showed the same binding as 11 (Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-Ser-Ahx, K M 1.7 μM). When the substrates were ranked by their caspase-3 catalytic efficiency (k cat/K M), more of a division between them was observed. Peptides 2 and 8, both bearing proline at the X2 position and alanine at the X1′, were poor substrates for caspase-3 with k cat/K M values of 1.8 and 3.2 μM–1 min–1, respectively. Within the series, 6 (Asp-Glu- Pro-Asp-Gly-Ahx) and 9 (Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-Ala-Ahx) had the highest catalytic efficiency (22.2 and 24.2 μM–1 min–1, respectively) proving that the enzyme can efficiently cleave substrates with proline at the X2 position. Based on the catalytic efficiency, the X1′ position overall had a slight preference for glycine and serine over alanine, especially with substrates incorporating proline at X2.

Table 2. Kinetic analysis of substrates 1–11 (n = 3) with caspase-3 and caspase-7.

| Caspase-3 |

Caspase-7 |

|||||

| Probe | K M (μM) | k cat (min–1) | k cat/K M (μM–1 min–1) | K M (μM) | k cat (min–1) | k cat/K M (μM–1 min–1) |

| 1 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 23.4 ± 1.4 | 10.3 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 10.2 ± 0.5 | 8.6 |

| 2 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 8.4 ± 0.3 | 1.8 | n/a c | n/a | n/a |

| 3 | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 20.1 ± 1.0 | 7.0 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 4 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 13.4 ± 0.5 | 7.8 | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 10.1 ± 0.6 | 3.4 |

| 5 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 36.5 ± 1.7 | 13.3 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 8.2 ± 0.5 | 3.5 |

| 6 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 58.4 ± 2.4 | 22.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 17.7 ± 0.6 | 8.4 |

| 7 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 20.4 ± 0.8 | 14.9 | 5.1 ± 0.9 | 19.9 ± 1.3 | 3.9 |

| 8 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 11.1 ± 0.5 | 3.2 | 27.5 ± 8.0 | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 0.14 |

| 9 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 53.3 ± 2.4 | 24.2 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 10.7 ± 0.3 | 3.2 |

| 10 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 30.7 ± 1.2 | 16.9 | 5.2 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 0.5 |

| 11 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 19.7 ± 0.9 | 11.7 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 6.4 ± 0.3 | 2.4 |

| MCA a | 13.5 ± 2.6 | 13.5 ± 1.3 | 1.0 | 15.1 ± 3.2 | 5.9 ± 0.7 | 0.4 |

| AFC b | 9.8 ± 1.9 | 14.7 ± 1.2 | 1.5 | 10.8 ± 2.8 | 11.6 ± 1.4 | 1.1 |

a MCA = MCA-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-Ala-Pro-Lys-DNP.

b AFC = Ac-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-AFC.

cCould not be determined.

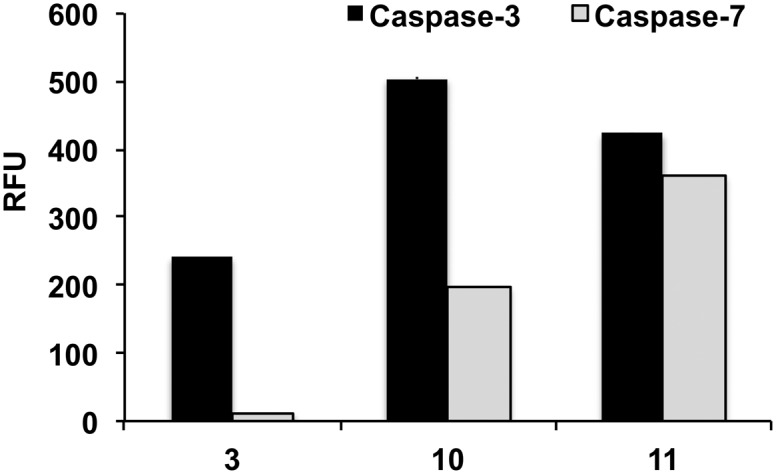

With caspase-7, substrates MCA and AFC had a K M values of 15.1 and 10.8 μM. At the X1′ position, caspase-7 had a clear preference for glycine with 1 and 6 having k cat/K M values of 8.6 and 8.4 μM–1 min–1, respectively. Substrates 2 (Asp-Glu-Pro-Asp-Ala) and 3 (Asp-Glu-Pro-Asp-Ser) showed negligible affinity to the enzyme (K M could not be determined). Remarkably 10, which was efficiently cleaved by caspase-3 (k cat/K M 16.9 μM–1 min–1), was a poor substrate for caspase-7 (k cat/K M 0.5 μM–1 min–1) further demonstrating that the sequence Asp-Glu-Pro-Asp-Ser-(Ahx) provides good specificity for caspase-3. Fig. 2 shows a direct comparison of fluorescence increase of probes 3, 10 and 11 after incubation with caspase-3 and caspase-7.

Fig. 2. Comparison of fluorescence increase (λ Ex/Em 485/525 nm) with substrates 3 (Asp-Glu-Pro-Asp-Ahx), 10 (Asp-Glu-Pro-Asp-Ser-Ahx) and 11 (Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-Ser-Ahx) at 3.1 μM (n = 3, standard deviation ±1.0–3.1 RFU) incubated with caspase-3 and caspase-7 (15 nM) for 60 min.

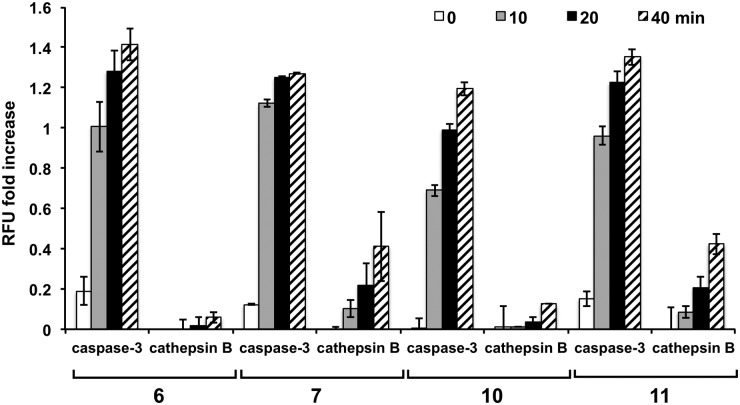

To further examine the specificity of the substrates, reactivity with cathepsin B was evaluated (ESI,† Fig. S5). The sequences incorporating proline at the X2 position (peptides 5, 6, 8, and 10) proved to be poor substrates for cathepsin B and were cleaved with a much lower efficiency than their valine counterparts, with 5 (Asp-Glu-Pro-Asp-Ahx) showing no increase in fluorescence. Substrates 6 and 10 showed significantly reduced cleavage by cathepsin B. To establish the relative affinity of cathepsin B and caspase-3 for the same substrate, the cleavage rates by the two enzymes were directly compared, with 5, 6, and 10 showing the highest selectivity towards caspase-3 even with a 1.7-fold higher cathepsin B concentration (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Comparison of activation by caspase-3 (15 nM) and cathepsin B (25 nM) with substrates (10 μM, n = 3) containing proline or valine at the X2 position (6 vs. 7 and 10 vs. 11). The fluorescencewas divided by the background fluorescence (no enzyme) to give a “RFU fold increase” for each probe ((RFUenzyme/RFUblank)–1). This was done to allow comparison with the reduced fluorescence of fluorescein in the acidic cathepsin buffer (pH 5).

Conclusions

11 FRET-based fluorogenic substrates, having a pentapeptide sequence with two variable positions, were designed and synthesised with the aim of identifying a caspase-3 selective peptide. Replacement of the valine with a proline in the traditional, non-selective Asp-Glu-Val-Asp recognition sequence yielded substrates with good selectivity over caspase-7 and cathepsin B. In particular peptide sequence Asp-Glu-Pro-Asp-Ser (substrates 3 and 10), was able to selectively quantify caspase-3 activity in vitro without notable caspase-7 and cathepsin B cross-reactivity. Furthermore, the binding affinities of these new substrates for caspase-3 were significantly increased (>3-fold) compared to the two widely used substrates MCA and AFC, compared to the two commercially available fluorogenic caspase-3 substrates, while also exhibiting good catalytic efficiency. The substrates based on Asp-Glu-Pro-Asp-Ser, have the potential to solve experimental issues caused by the lack of enzyme selectivity of commonly used substrates, providing a more accurate analysis of caspase-3 activity in cancer and beyond. Application of these selective substrates to probes enabling caspase-3 imaging in cell-based assays is currently underway.

Acknowledgments

Cancer Research UK is thanked for funding MM, Caja Madrid and Ramon Areces Foundation for funding AMPL, and Dr Scott Webster (QMRI, Edinburgh) for the extensive use of his plate reader.

Footnotes

References

- Ameisen J. C. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:367–393. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata S. IUBMB Life. 2006;58:358–632. doi: 10.1080/15216540600746401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander R. M. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1365–1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Olsson M., Zhivotovsky B. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:1441–1449. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Thompson C. B. Science. 1995;267:1456–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.7878464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) McIlwain D. R., Berger T., Mak T. W., Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol., 2013, 5 , 2 –28 , (a008656) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang I., Lin J. Eur. J. Cancer. 1999;35:1517–1525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. C., Cullen S. P., Martin S. J. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:231–241. doi: 10.1038/nrm2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulda S., Gorman A. M., Hori O., Samali A. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2010;1:1–23. doi: 10.1155/2010/214074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Devarajan E., Sahin A. A., Chen J. S., Krishnamurthy R. R., Aggarwal N., Brun A.-M., Sapino A., Zhang F., Sharma D., Yang X.-H., Tora A. D., Mehta K. Oncogene. 2002;21:8843–8851. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) D'Amelio M., Sheng M., Cecconi F. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:700–709. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shi Y. J. Cancer Mol. 2005;1:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ai X., Butts B., Vora K., Li W., Tache-Talmadge C., Fridman A., Mehmet H. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e205. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozarowski P., Huang X., Halicka D. H., Lee B., Johnson G., Darzynkiewicz Z. Cytometry, Part A. 2003;55:50–60. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.10074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Bullok K., Piwnica-Worms D. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:5404–5407. doi: 10.1021/jm050008p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Johnson J. R., Kocher B., Barnett E. M., Marasa J., Piwnica-Worms D. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012;23:1783–1793. doi: 10.1021/bc300036z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Fu A., Luo K. Q. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012;418:641–646. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Becker J. W., Rotonda J., Soisson S. M., Aspiotis R., Bayly C., Francoeur S., Gallant M., Garcia-Calvo M., Giroux A., Grimm E., Han Y., McKay D., Nicholson D. W., Peterson E., Renaud J., Roy S., Thornberry N., Zamboni R. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:2466–2474. doi: 10.1021/jm0305523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ganesan R., Jelakovic S., Mittl P. R. E., Caflisch A., Grütter M. G. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. F: Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2011;67:842–850. doi: 10.1107/S1744309111018604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Köhler C., Orrenius S., Zhivotovsky B. J. Immunol. Methods. 2002;265:97–110. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tyas L., Brophy V. A., Pope A., Rivett A. J., Tavaré J. M. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:266–270. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Savitsky A. P., Rusanov A. L., Zherdeva V. V., Gorodnicheva T. V., Khrenova M. G., Nemukhin A. V. Theranostics. 2012;2:215–226. doi: 10.7150/thno.3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Maxwell D., Chang Q., Zhang X., Barnett E. M., Piwnica-Worms D. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:702–709. doi: 10.1021/bc800516n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cen H., Mao F., Aronchik I., Fuentes R. J., Firestone G. L. FASEB J. 2008;22:2243–2252. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-099234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) McStay G. P., Salvesen G. S., Green D. R. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:322–331. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) V Onufriev M., Yakovlev A. A., Lyzhin A. A., Stepanichev M. Y., Khaspekov L. G., Gulyaeva N. V. Biochem., Biokhim. 2009;74:281–287. doi: 10.1134/s0006297909030067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Berger A. B., Sexton K. B., Bogyo M. Cell Res. 2006;16:961–963. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Vickers C. J., González-Páez G. E., Wolan D. W. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013;8:1558–1566. doi: 10.1021/cb400209w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vickers C. J., González-Páez G. E., Wolan D. W. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014;9:2199–2203. doi: 10.1021/cb500586p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poreba M., Kasperkiewicz P., Snipas S. J., Fasci D., Salvesen G. S., Drag M. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:1482–1492. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Talanian R. V., Quinlan C., Trautz S., Hackett M. C., Mankovich J. A., Banach D., Ghayur T., Brady K. D., Wong W. W. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:9677–9682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Thornberry N. A., Rano T. A., Peterson E. P., Rasper D. M., Timkey T., Garcia-Calvo M., Houtzager V. M., Nordstrom P. A., Roy S., Vaillancourt J. P., Chapman K. T., Nicholson D. W. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:17907–17911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.17907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Xue D., Horvitz H. R. Nature. 1995;377:248–251. doi: 10.1038/377248a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bump N. J., Hackett M., Hugunin M., Seshagiri S., Brady K., Chen P., Ferenz C., Franklin S., Ghayur T., Li P. Science. 1995;269:1885–1888. doi: 10.1126/science.7569933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Berger A. B., Witte M. D., Denault J.-B., Sadaghiani A. M., Sexton K. M. B., Salvesen G. S., Bogyo M. Mol. Cell. 2006;23:509–521. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Edgington L. E., Berger A. B., Blum G., Albrow V. E., Paulick M. G., Lineberry N., Bogyo M. Nat. Med. 2009;15:967–973. doi: 10.1038/nm.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sexton K. B., Witte M. D., Blum G., Bogyo M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:649–653. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.10.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Stennicke H. R., Renatus M., Meldal M., Salvesen G. S. Biochem. J. 2000;350:563–568. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wolf B. B. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:20049–20052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nicholson D. W. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:1028–1042. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Mochón J. J., Bialy L., Bradley M. Org. Lett. 2004;6:1127–1129. doi: 10.1021/ol049905y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.