ABSTRACT

Objective:

Jamaica is one of the largest countries in the Caribbean with a population of 2 706 500. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in Jamaica is high, while that of tuberculosis (TB) is recorded to be low. In this study, we have estimated the burden of serious fungal infections and some other mycoses in Jamaica.

Methods:

All published papers reporting on rates of fungal infections in Jamaica and the Caribbean were identified through extensive search of the literature. We also extracted data from published papers on epidemiology and from the World Health Organization (WHO) TB Programme and UNAIDS. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA), allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) and severe asthma with fungal sensitization (SAFS) rates were derived from asthma and TB rates. Where there were no available data on some mycoses, we used specific populations at risk and frequencies of fungal infection of each to estimate national prevalence.

Results:

Over 57 600 people in Jamaica probably suffer from serious fungal infections each year, most related to ‘fungal asthma’ (ABPA and SAFS), recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis and AIDS-related opportunistic infections. Histoplasmosis is endemic in Jamaica, though only a few clinical cases are known. Pneumocystis pneumonia is frequent while cryptococcosis and aspergillosis are rarely recorded. Tinea capitis was common in children. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis is very common (3154/100 000) and candidaemia occurs. Subcutaneous mycoses such as chromoblastomycosis and mycetoma also seem to be relatively common.

Conclusion:

Local epidemiological studies are urgently required to validate or modify these estimates of serious fungal infections in Jamaica.

Keywords: Estimates, Jamaica, serious fungal infection

RESUMEN

Objetivo:

Jamaica es uno de los países más grandes del Caribe con una población de 2 706 500. La prevalencia del virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH) en Jamaica es alta, mientras que la de la tuberculosis (TB) se registra como baja. En este estudio, hemos estimado la carga de las infecciones fúngicas graves y algunas otras micosis en Jamaica.

Métodos:

Todos los trabajos publicados sobre las tasas de infecciones micóticas en Jamaica y el Caribe se identificaron mediante una búsqueda extensa de la literatura. También se extrajeron datos de artículos publicados sobre epidemiología de UNOSIDA y el programa Estrategia Alto a la Tuberculosis, impulsada por la OMS. Las tasas de aspergilosis pulmonar crónica (APC), aspergilosis broncopulmonar alérgica (ABPA) y asma grave con sensibilización fúngica (SAFS) fueron derivadas de las tasas de asma y TB. Donde no había datos disponibles sobre algunas micosis, usamos poblaciones específicas en riesgo y las frecuencias de infección fúngica de cada una para llegar a un estimado de la prevalencia nacional.

Resultados:

Más 57600 personas en Jamaica probablemente sufren de infecciones micóticas graves cada año, la mayor parte relacionadas con “asma fúngica” (ABPA y SAFS), candidiasis vulvovaginal recurrente e infecciones oportunistas relacionadas con el SIDA. La histoplasmosis es endémica en Jamaica, aunque se conocen sólo unos pocos casos clínicos. La neumonía por pneumocistis es frecuente, aunque raramente se registran la criptococosis y la aspergilosis. La tinea capitis o tiña de la cabeza en niños es común. La candidiasis vulvovaginal recurrente es muy común (3154/100 000) y la candidemia ocurre. Las micosis subcutáneas, tales como la cromoblastomicosis y la micetoma, también parecen ser relativamente común.

Conclusión:

Es necesario realizar urgentemente estudios epidemiológicos locales a fin de validar o modificar estas valoraciones acerca de las infecciones fúngicas graves en Jamaica.

INTRODUCTION

The health importance of invasive fungal infections (IFIs) has increased during the past two decades in Latin America and worldwide, and the number of patients at risk has risen dramatically. Working habits and leisure activities have also been a focus of attention by public health officials, as endemic mycoses have provoked a number of outbreaks. The first case of Conidiobolus coronatus infection in the world was recorded in Jamaica (1). Histoplasma capsulatum is endemic in certain caves in the island (2, 3). In a study of secondary spontaneous pneumothorax in 81 patients (4), the underlying predisposing disorders were chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases [COPD] (47.8%), tuberculosis (26.1%), asthma (13%) and Pneumocystis pneumonia (4%).

The information on the incidence and prevalence of fungal infections is lacking in most developing counties, particularly those in the Caribbean. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence in Caribbean countries is high, estimated at 1%, varying from 0.9–2.0% among different Caribbean countries (5). Hence, complicating fungal infections are probably common. Jamaica is one of the largest countries in the Caribbean with a population of 2 706 500, according to the latest official estimate provided in 2011 by the Statistical Institute of Jamaica (6). Though cases of cryptococcosis, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP), histoplasmosis and aspergillosis are recorded, not much is known about the prevalence of these and other mycotic infections in Jamaica. It is essential for the public health authorities, and physicians and surgeons to know the prevalence of important fungal infections, and the type of morbidity caused by them for their management and health resource planning. Hence, we considered it desirable to estimate the burden of serious fungal infections in Jamaica. We estimated the burden of fungal infections in Jamaica from published literature and modelling.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Population figures for 2011 were obtained from the Statistical Institute of Jamaica (6). We extracted data from published papers on epidemiology and from the World Health Organization (WHO) Stop TB Programme (7) and UNAIDS (8). We also searched for relevant literature through MEDLINE, PubMed, MedFacts, and several search engines, using different sets of key words. Where no data existed, we used specific populations at risk and fungal infection frequencies in those populations to estimate national incidence or prevalence depending on the condition. The search for data extended over several months during 2013–2014. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis [CPA] (9), allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis [ABPA] (10) and severe asthma with fungal sensitization [SAFS] (11) rates were based on asthma and tuberculosis (TB) rates. Asthma rates (doctor diagnosed asthma) in 20–40 year olds of 10.6% were taken from the data of Kahwa et al (12), and assumed to relate to all adulthood, despite a rise in the incidence in 65–92 year olds to 12.8% of current asthma [with the same rate of doctor diagnosed asthma] (12). Other assumptions were based on incidence rates reported in the local and international literature (11, 13, 14). The denominators included the overall Jamaican population, number of patients with HIV/AIDS and respiratory diseases.

RESULTS

The estimated burden of serious fungal infections is presented in the Table. The Jamaican population was estimated to be 2 706 500 million people, of whom 29% are children (0–14 years) and 11% are ≥ 60 years old. The adult asthma population was estimated at 204 000.

Table 1. Estimated burden of fungal disease in Jamaica.

| Fungal condition | Number of infections per underlying disorder per year | Total burden | Rate/100K | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | HIV/AIDS | Respiratory | Cancer/Tx | ICU | |||

| Oesophageal candidiasis | ? | 2100 | – | ? | 2100 | 77.2 | |

| Candidaemia | – | – | – | 95 | 41 | 136 | 5 |

| Candida peritonitis | – | ? | – | – | 20 | 20 | 0.8 |

| RVVC (4x/year) | 42 885 | – | – | – | – | 42 885 | 3154 |

| ABPA | – | 5116 | – | – | 5116 | 188 | |

| SAFS | – | 6753 | 6753 | 248 | |||

| CPA | – | – | 82 | – | – | 82 | 3.0 |

| IA | – | – | – | ? | ? | ? | |

| Mucormycosis | – | – | – | ? | – | ? | ? |

| CM | ? | 140 | – | – | – | 140 | 5 |

| PCP | – | 350 | ? | ? | – | 350 | 13 |

| Histoplasmosis | ? | ? | ? | – | – | ? | ? |

| Fungal keratitis | ? | – | – | – | – | – | ? |

| Tinea capitis | ? | – | – | – | – | ? | ? |

| Total burden estimated | 42 885+ | 2590+ | 11 950+ | 112+ | 61+ | 57 598+ | |

Tx = treatment; ICU = intensive care unit; RVVC = recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis; ABPA = allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; SAFS = severe asthma with fungal sensitization; CPA = chronic pulmonary aspergillosis; IA = invasive aspergillosis; CM = cryptococcal meningitis; PCP = Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia; - = no cases likely, so not estimable; ? = estimate not possible but some or many cases likely

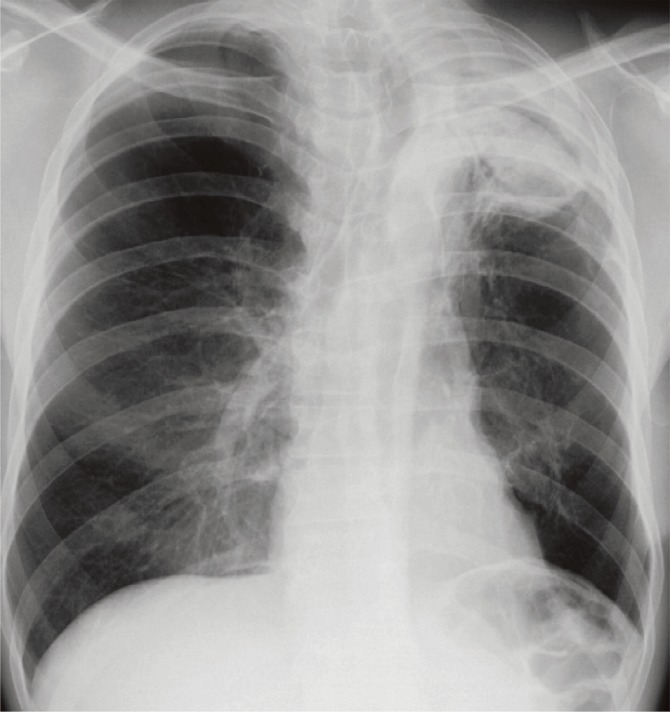

Using a 2.5% rate for ABPA and 3% for SAFS based on other studies (10, 11), Jamaica has 5116 ABPA cases and 6753 SAFS cases (188 and 248/100 000, respectively). Only 98 cases of pulmonary TB were reported in 2011, so CPAis probably rare, with an estimated prevalence of 14 cases after TB (1/100 000), estimated at 15% of the total CPA caseload of 82 cases, assuming a 15% annual mortality. The Figure shows a radiograph of a case of CPA with aspergilloma in a 53-year old HIV-negative male, developing after anti-tuberculous treatment.

Figure. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis with aspergilloma (in the left upper lobe) in a 53-year old HIV-negative Jamaican male, developing after one year of anti-tuberculous treatment. His baseline Aspergillus IgG titre was 741 mg/L (0–40). As a smoker, he also had moderate emphysema.

An estimated 42 885 women have four or more attacks of vaginal candidiasis annually (6% of women 15–50 years; 714 745 females). If 5% and 8% rates were used, the burden would be 30 000 and 54 000. Using a common international figure for the incidence of candidaemia of 5/100 000, 136 cases of candidaemia are estimated to occur each year, and 20 cases of Candida peritonitis in surgical patients. We did not estimate Candida peritonitis complicating chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis.

The burden of HIV/AIDS is estimated to be over 27 000 patients –1.6% of all adults – of whom 14 000 are not receiving antiretroviral (ARV) therapy and have CD4 counts < 350/uL (15). Assuming 50% and 15% of these patients develop oral or oesophageal candidiasis annually, 6300 and 2100 cases, respectively of each would be expected. Assuming 10% of those not on ARVs progress to a life-threatening opportunistic infection each year, and that the rate of PCP is 25% and cryptococcal meningitis 10%, 1120 PCP and 140 cryptococcal meningitis cases would be expected in AIDS patients annually.

It was not possible to estimate the burden of histoplasmosis, invasive aspergillosis, mucormycosis, mycetoma and fungal keratitis due to paucity of data.

DISCUSSION

We estimate that over 57 600 persons in Jamaica probably suffer from serious fungal infections each year, most related to ‘fungal asthma’ (ABPA and SAFS), recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) and AIDS-related opportunistic infections. Most of the reports of Pneumocystis pneumonia are based on presumptive diagnosis; implementation of high quality immunofluorescence microscopy or molecular diagnosis would allow more precise estimates, especially in non-AIDS patients. Likewise, testing for IgE and fungal allergy with specific IgE or skin prick tests could open up oral antifungal therapy to the estimated 30 000 asthmatic adults with fungal allergy. No estimates of paediatric fungal infections were attempted.

A study on the epidemiology of mycotic vulvovaginitis in 354 women aged 15–50 years showed Candida albicans to be by far the predominant aetiological agent followed by C tropi-calis (16). We estimate that over 42 000 women suffer from at least four attacks of recurrent VVC annually. This carries a substantial psychological and modest economic toll: during an acute episode of VVC, 68% of women reported depression/anxiety problems, and 54% between episodes, compared to less than 20% in the general population. Also, the impact on productivity was estimated at 33 lost work hours per year on average, corresponding to estimated costs between €266/year and €1130/year depending on the European country (17). Clearly, this work from Europe and the United States of America may not relate to the Jamaican female population, but a substantial impact on quality of life is likely. Candidaemia is also recognized in Jamaica, but no epidemiological study has been published (18).

In Jamaica, evidence of endemicity of histoplasmosis emerged in 1978, when 24 of a group of 27 cavers, who had visited St Clare Cave in St Catherine, were confirmed radiologically and serologically to have acute pulmonary histoplasmosis (2). Some were off work for several weeks and three were hospitalized, one of them with severe symptoms persisting over five weeks. All those who had never taken part in cave exploration on the island had negative skin tests, and all those who had explored two or more caves were histoplasmin positive. However, actual outbreaks of histoplasmosis are rare in Jamaica (2). Fincham and DeCeulaer (3) studied the incidence of histoplasmin sensitivity in 20 people with a history of cave exploration in Jamaica, and 10 without such exposure. Fourteen exposed subjects had a positive skin test (70%) and in 11 of these, the induration was greater than 10 mm in diameter. This was clear and further indirect evidence that histoplasmosis is endemic in Jamaica (3). Later, Ajello, as cited by Fincham (19), recovered Histoplasma capsulatum from the soil samples collected from the cave. In an earlier study, skin testing of a sample of students and staff (n = 338) of the University Hospital of the West Indies at Mona had shown a 10% rate of positive skin reactivity to the antigen histoplasmin (2). A further study on expatriate white European subjects who had lived on the island for 20–30 years showed that only those with caving experience were positive for antibodies to histoplasmin (19). Later, several other cases of clinical infections due to Histoplasma capsulatum were described (19, 20). In a one-year study of 665 HIV-infected patients, 46% of whom had CD4 cell counts < 200/uL, 23 had PCP and three had cryptococcal meningitis (21), but histoplasmosis was not diagnosed. It may be mentioned here that six cases of cryptococcal meningitis were known from Jamaica as far back as in 1980 and there is a recent report of a case of systemic cryptococcosis with cutaneous manifestations (22, 23).

In an epidemiological study of fungaemia at the University Hospital of the West Indies, non-Candida albicans (mainly C tropicalis) were the predominant agents followed by C albicans (18). Acase of disseminated trichosporonosis due to Trichosporon asahii involving the lungs and brain was described in a 44-year old hypertensive, diabetic woman with partial and full-thickness thermal burns involving 50% of her body (24). Following this, 63 cases with T asahii infection including four with disseminated diseases were identified among intensive care unit patients at a medical centre in Jamaica (25). A case of fungaemia due to a rare agent, Paecilomyces lilacinus, has been also described in a neonate (26).

Regarding the prevalence of subcutaneous mycoses, several cases of mycetoma due to Nocardia species, Acremonium sp and Madurella mycetomatis have been reported (27–30). Bansal and Prabhakar (31) reported 31 histologically confirmed cases of chromoblastomycosis with positive cultures of Fonsecea pedrosoi in 16 of them. There is also a report of subcutaneous infection due to Lasiodiplodia theobromae in a Canadian woman, with evidence of infection originating in Jamaica following an injury to the left leg from a wooden staircase (32).

Concerning the incidence of superficial fungal infections, tinea capitis is very frequent in children (33), possibly because the population is predominantly of African ancestry (34, 35). The predominant aetiological agents of tinea capitis were recorded to be Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum audouinii. Microsporum gypseum was represented by one isolate in this study, though it had been found frequently in the soil (50% of samples) in Jamaica (36).

Local epidemiological studies are urgently required to validate or modify these estimates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bras G, Gordon CC, Emmons CW, Prendegast KM, Sugar M. A case of phycomycosis observed in Jamaica: infection with Entomophthora coronata. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1965;14:141–145. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1965.14.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fincham AG. Histoplasmosis in Jamaican caves. Trans Brit Cave Res Assoc. 1978;5:225–228. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fincham AG, DeCeulaer K. Histoplasmin sensitivity among the cavers in Jamaica. West Indian Med J. 1980;29:22–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams E, Cawich S, Irwine R, Ramphal P. Epidemiology of spontaneous pneumothorax in Jamaica. Intern J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;12:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Figueroa JP. The HIV epidemic in the Caribbean: meeting the challenges of achieving universal access to prevention, treatment and care. West Indian Med J. 2008;57:195–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Statistical Institute of Jamaica . Population by sex 2002–2013. Kingston: STATIN; 2014. Available from: http://statinja.gov.jm/Demo_Social-Stats/population.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . Tuberculosis country profiles. Geneva: WHO; Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/country/data/profiles/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.AVERT . HIV and AIDS in the Caribbean. Brighton: AVERT; [[updated 2015 May 01]]. Available from: http://www.avert.org/caribbean-hiv-aids-statistics.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denning DW, Pleuvry A, Cole DC. Global burden of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis as a sequel to tuberculosis. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:864–872. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.089441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denning DW, Pleuvry A, Cole DC. Global burden of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and its complication chronic pulmonary aspergillsois in adults. Med Mycol. 2013;51:361–370. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.738312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fungal Infection Trust . How common are fungal diseases? Macclesfield: Fungal Infection Trust; 2011. [[updated 2013 Nov 27]]. Available from: http://www.fungalinfectiontrust.org/How%20Common%20are%20Fungal%20Diseases5.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahwa EK, Younger NO, Waldron NK, Bailey KA, Knight-Madden JM, Wint YB, et al. The status of asthma in Jamaica. West Indian Med J. 2011;60(Suppl 4):17–18. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez MA, Fernandez DM, Otero JF, Miranda S, Hunter R. The shape of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Puerto Rico. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2000;7:377–383. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892000000600004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Báez-Feliciano DV, Thomas JC, Gómez MA, Miranda S, Fernández DM, Velázquez M, et al. Changes in the AIDS epidemiologic situation in Puerto Rico following health care reform and the introduction of HAART. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2005;17:92–101. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892005000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jamaica country progress report. Global AIDS response progress report 2014. 2014 Kingston: National Family Planning Board and National HIV/STD Control Programme. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2014countries/JAM_narrative_report_2014.pdf.

- 16.Jackson ST, Mullingo AL, Rainford L. Epidemiology of mycotic vulvovaginitis and use of antifungal agents in suspected mycotic vulvovaginitis and its implications in clinical practice. West Indian Med J. 2005;54:192–195. doi: 10.1590/s0043-31442005000300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aballéa S, Guelfucci F, Wagner J, Khemin A, Dietz JP, Sobel J, et al. Subjective health status and health-related quality of life among women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidosis (RVVC) in Europe and the USA. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:169–169. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicholson A, Rainford L. The epidemiology of fungaemia at the University Hospital of the West Indies, Kingston, Jamaica. West Indian Med J. 2009;58:580–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fincham AG. Jamaica underground: the caves, sinkholes and underground rivers of the island. Kingston: University of the West Indies Press; 1997. A word about histoplasmosis; pp. 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicholson AM, Rainford L, Elliott V, Christie CDC. Disseminated histoplasmosis and AIDS at the University Hospital of the West Indies. West Indian Med J. 2004;53:126–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrow G, Clarke TR, Carrington D, Harvey K, Barton EN. An analysis of three opportunistic infections in an outpatient HIV clinic in Jamaica. West Indian Med J. 2010;59:393–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Falconer H, Terry SI, Spencer H, Cross JN, King SD, Chen W, et al. Cryptococcosis in the West Indies. West Indian Med J. 1980;29:142–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mah-Lee R, Barrow G. A case of systemic cryptococcal disease in HIV infection. West Indian Med J. 2013;62:374–376. doi: 10.7727/wimj.2013.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heslop OD, Nyi Nyi MP, Abbot SP, Rainford LE, Castle DM, Coard KCM. Disseminated trichosporonosis in a burn patient: meningitis and cerebral abscess due to Trichosporon asahii. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:405–408. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05028-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fanfair RN, Heslop O, Etienne K, Rainford L, Roy M, Gade L, et al. Trichosporon asahii among intensive care unit patients at a medical center in Jamaica. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:638–641. doi: 10.1086/670633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson ST, Smikle MF, Antoine MG, Roberts GD. Paecilomyces lilacinus fungemia in a Jamaican neonate. West Indian Med J. 2006;55:360–360. doi: 10.1590/s0043-31442006000500016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saksun JN, Kane J, Sachter RK. Mycetoma caused by Nocardia madurae. Can Med Assoc J. 1978;119:911–914. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hay RJ. Mycoses imported from West Indies: a report of three cases. Postgrad Med J. 1979;55:603–604. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.55.647.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fletcher CL, Moore MK, Hay RJ. Eumycetoma due to Madurella mycetomatis acquired in Jamaica. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:1018–1021. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pilsczek FH, Augenbraun M. Mycetoma fungal infection: multiple organisms as colonizers or pathogens? Revista Soc Brasil Med Trop. 2001;40:463–465. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822007000400017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bansal AS, Prabhakar P. Chromomycosis: a twenty-year analysis of histologically confirmed cases in Jamaica. Trop Geog Med. 1989;41:221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Summerbell S, Krajden S, Levine R, Fuksa M, Richard S. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis caused by Lasiodiplodia theobromae and successfully treated surgically. Med Mycol. 2004;42:543–547. doi: 10.1080/13693780400005916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.East-Innis A, Rainford L, Dunwell P, Barrett-Robinson D, Nicholson AM. The changing pattern of tinea capitis in Jamaica. West Indian Med J. 2006;55:85–88. doi: 10.1590/s0043-31442006000200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hackett BC, O'Connell K, Cafferkey M, O'Donnell BF, Keane FM. Tinea capitis in a paediatric population. Ir Med J. 2006;99:294–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coloe JR, Diab M, Moennich J, Diab D, Pawaskar M, Balkrishnan R, et al. Tinea capitis among children in the Columbus area, Ohio, USA. Mycoses. 2010;53:158–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gugnani HC, Sharma S, Wright K. A preliminary study on the occurrence of keratinophilic fungi in soils of Jamaica. Revista Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2014;56:231–234. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652014000300009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]