Abstract

Purpose of review

Combined pegylated interferon-α and ribavirin remain the standard therapy for pediatric hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in 2016, but direct acting antivirals (DAAs) with greatly improved efficacy and safety are now approved for adults. Here we review the major classes of DAAs and their anticipated use for treatment and potentially prevention of HCV in children.

Recent findings

Currently approved DAAs target the viral protease, polymerase, and NS5A, a protein involved in viral replication and assembly. In combination, they have lifted sustained virologic response rates to over 90% for multiple HCV genotypes, and the rich DAA pipeline promises further improvements. Clinical trials of interferon-free DAA regimens have been initiated for children ages 3–17 years. The first efficacy trial of a preventative HCV vaccine for adults is also underway. While awaiting a vaccine, there is hope that increased DAA uptake may prevent pediatric HCV infections by shrinking the pool of infectious persons.

Summary

Interferon-free DAA regimens have revolutionized therapy for HCV-infected adults and pending results of pediatric trials will likely do the same for HCV-infected children. If widely deployed, particularly amongst individuals likely to transmit HCV, DAA therapies may also help reduce new vertically- and horizontally-acquired pediatric infections.

Keywords: Hepatitis C virus, direct acting antiviral, therapy, pediatrics, vertical transmission

Introduction

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) remains a major cause of liver disease more than a quarter century since its discovery. An estimated 115–185 million individuals have serologic evidence of HCV infection, including roughly 11 million children under the age of 15 years [1, 2]. Vertical transmission, injection drug use (IDU), and iatrogenic exposures account for most pediatric infections. While some of these infections resolve spontaneously, approximately 60–80% of vertically- and horizontally-acquired pediatric HCV infections persist indefinitely [3–5]. Persistent hepatitis C infections predispose to complications including hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Of individuals who acquire HCV as adults, approximately 10–20% develop cirrhosis after 20–30 years of infection, with a subsequent 3–6% annual risk of hepatic decompensation and 1–5% annual risk of hepatocellular carcinoma [6]. Liver disease progresses more slowly in children, with only 1–2% of those infected as infants developing cirrhosis during childhood [7, 8]. Nevertheless, most children who undergo liver biopsy demonstrate some degree of liver inflammation, often with mild fibrosis, and there remains concern that without treatment a significant proportion of HCV-infected children could go on to develop advanced liver disease over their lifetime [9–11].

Pediatric HCV therapy in 2016

Successful treatment of HCV can halt progression of liver disease and prevent transmission to others, but in 2016 most HCV-infected children are not treated. An obvious reason is that most pediatric HCV infections are not diagnosed; by one estimate only 5–15% of HCV-infected children in the U.S. are identified [12]. Secondly, limitations of approved therapies coupled with the mild course of pediatric HCV result in deferral of therapy for many children with known HCV infection. The standard therapy for HCV-infected children aged 3–17 years is combination pegylated interferon-alpha (pegIFNα) and ribavirin (RBV) [3]. For genotype (GT) 1, the most prevalent HCV genotype in the U.S. and globally [2], 48 weeks of therapy results in a sustained virologic response (SVR) in less than 50% of children [13]. GT2 and GT3 infections are more responsive to pegIFNα/RBV therapy, with SVR rates approaching 90% in pediatric trials [13, 14]. Although children tolerate this regimen better than adults, a substantial proportion still experience side effects including influenza-like symptoms, leukopenia, and anemia. Beyond this, interferon-based therapies transiently impair vertical growth [13, 14]. Given the slow pace of liver disease in most HCV-infected children, suboptimal efficacy and substantial toxicity of pegIFNα/RBV, and stunning performance of new all-oral interferon-free direct acting antiviral (DAA) regimens in adults, many persistently infected children are being “warehoused” until they too have access to all-oral DAA therapies [15]. However, standard treatment without delay may be advised in the rare instance of rapidly progressive pediatric liver disease, particularly when caused by the more interferon-responsive genotypes 2 and 3 [3, 15].

Origins of the DAA revolution

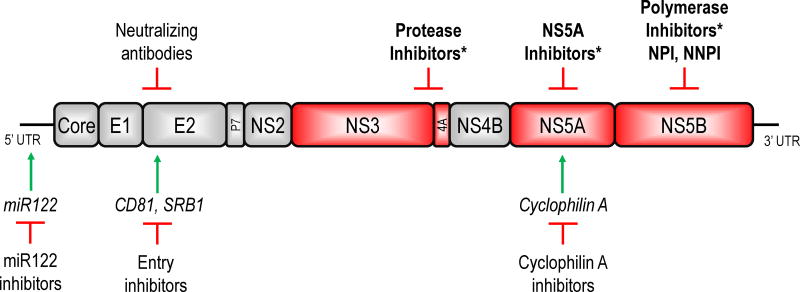

Drug discovery efforts for HCV were hampered for years by inability to culture the virus in cell culture. Eventual development of a subgenomic replicon system in 1999 [16] and a pseudoparticle system in 2003 [17] facilitated studies of HCV intracellular replication and viral entry. Another major breakthrough came in 2005 with discovery of a genotype 2 virus capable of replicating in a permissive hepatoma cell line [18]. Using these systems as well as insights gained from resolution of the three dimensional structures of several HCV proteins, antivirals have been developed by rational drug design and compound screening [19, 20]. Experimental targets of anti-HCV therapies now include the envelope glycoproteins E1 and E2, non-structural viral proteins NS3, NS5A, and NS5B, and host factors affecting the viral entry and replication including scavenger receptor B1 (SRB1), CD81, cyclophilin A, and miR122 (Figure 1) [19, 21, 22]. This review will focus on inhibitors of the viral NS3/4A protease, NS5A, and the NS5B polymerase, drug classes that are already approved for use in adults and most likely to enter clinical care for children in the near term.

Figure 1.

A schematic of the HCV polyprotein and targets of antiviral therapies. The positive-stranded RNA genome of HCV encodes a single polyprotein approximately 3000 amino acids in length that is cleaved by host and viral proteases into 10 individual proteins. Each of these proteins is essential for the viral life cycle and a potential therapeutic target. Currently approved direct acting antivirals (asterisks) target the viral NS3/4A protease, NS5A, and the NS5B polymerase proteins. Compounds directed at host factors (italics) critical for viral replication such as miR122, cyclophilin A, and viral receptors CD81 and SRB1 have also shown therapeutic potential.

NS3/4A protease inhibitors

The first DAAs to enter clinical practice targeted the HCV NS3/4A protease. This heterodimeric serine protease cleaves 4 sites along the viral polyprotein to release individual HCV proteins [20, 23]; it also cleaves several adaptor proteins in innate immune signaling pathways to counter host antiviral defenses [24, 25]. Compounds that bind the protease catalytic site potently reduce HCV replication. First generation protease inhibitors telaprevir and boceprevir were approved in 2011 for use in combination with pegIFNα/RBV to treat adults chronically infected with HCV GT1. Addition of either one of these drugs boosted SVR rates in treatment-naïve individuals from 40–44% to 67–75% [26, 27] and also benefitted treatment-experienced populations [19, 28].

Despite being a significant milestone in the evolution of HCV therapy, the advent of “triple therapy” combining protease inhibitors and pegIFNα/RBV left much room for improvement. SVR rates were still less than desired, particularly in populations such as prior null-responders to pegIFNα/RBV [19]. Telaprevir and boceprevir also added significant toxicity to an already difficult regimen, including rash in the case of telaprevir and exacerbations of ribavirin-induced anemia with both [19]. The drugs also had a low genetic barrier to resistance; any of a number of single nucleotide point mutations could render viruses resistant [29]. Substantial diversity of the viral protease across genotypes meant that the drugs had limited cross-genotypic activity. Finally, frequent drug-drug interactions presented challenges [23]. Studies of both telaprevir and boceprevir were initiated in children (and completed in the case of telaprevir), but neither drug is expected to be a component of future pediatric HCV care given the rapid development of safer and more effective alternatives (NCT01701063 and NCT01425190; www.clinicaltrials.gov).

NS3/4A inhibitors are still expected to be important components of future DAA regimens. After telaprevir and boceprevir, the so-called “first-generation, second-wave” protease inhibitors simeprevir and paritaprevir were approved in 2013 and 2014, demonstrating improved efficacy and less toxicity. Second generation protease inhibitors that boast pan-genotype activity and higher barriers to resistance have now reached phase III clinical trials. A summary of protease inhibitors that are now approved or in advanced clinical trials can be found in Table I.

Table 1.

Characteristics of direct-acting antiviral drug classes approved for use in HCV-infected adults

| Characteristics | Protease inhibitors | NS5A inhibitors | NS5B nucleoside inhibitors (NPI) | NS5B non-nucleoside inhibitors (NNPI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potency | High | High | High | Variable |

| Cross-genotype activity | Limited | Broad | Broad | Variable |

| Barrier to resistance | Low | Low; prolonged persistence of resistant variants | High; resistant variants replicate poorly | Low |

| DAAs approved* or in phase 2 or 3 clinical trials | Telaprevir* Boceprevir* Simeprevir* Paritaprevir* Asunaprevir Sovaprevir Vaniprevir Grazoprevir ABT-493 GS-9857 |

Ledipasvir* Ombitasvir* Daclatasvir* Elbasvir Velpatasvir Ravidasvir Samatasvir Odalasvir ABT-530 MK-8408 |

Sofosbuvir* MK-3682 |

Dasabuvir* Beclabuvir GS-9669 |

NS5A inhibitors

NS5A is a non-enzymatic protein that participates in the formation of the HCV replicase complex and in viral particle assembly. NS5A inhibitors block both functions and are among the most potent DAA for HCV [26]. Approved NS5A inhibitors have broad cross-genotypic activity, with daclatasvir classified as pan-genotypic. The NS5A protein lacks a human homolog, and its inhibitors are well tolerated [26]. An important downside of this class is its low barrier to resistance. Moreover, many NS5A resistant variants replicate efficiently and can persist for long periods in individuals after treatment failure [30]. Currently approved first generation NS5A inhibitors include daclatasvir, ledipasvir, and ombitasvir, and second generation DAAs are in development (Table 1).

NS5B polymerase inhibitors

The NS5B protein functions as the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase for HCV and has been a major focus of drug development efforts. Inhibitors of NS5B fall into one of two classes: nucleos(t)ide polymerase inhibitors (NPI) and non-nucleos(t)ide polymerase inhibitors (NNPI).

NPI are nucleoside or nucleotide analogues that are incorporated into the emerging RNA strand by the NS5B polymerase, preventing incorporation of additional nucleotides. NPI demonstrate broad cross-genotypic activity due to the highly conserved nature of the NS5B active site. Although single amino acid substitutions confer resistance to NPI, emergence of resistant variants is rare because these variants tend to exhibit significantly impaired viral replicative fitness without additional compensatory mutations [31]. NPI are delivered as pro-drugs requiring hepatic conversion to limit systemic exposure. Toxicity has nevertheless halted the development of numerous NPI, in some cases thought related to off-target effects on mitochondrial RNA polymerases [31]. At present the only NPI approved for treatment of chronic HCV infection is sofosbuvir, a well-tolerated and potent nucleotide NS5B inhibitor with nearly pan-genotypic activity. Sofosbuvir was a component of the first all-oral DAA regimens for HCV and has entered pediatric trials (NCT02175758, NCT02249182).

The NNPI class comprises diverse antivirals that bind any one of five non-catalytic sites on NS5B, limiting its ability to undergo the conformational changes needed for polymerase activity [31]. As a group they tend to have low barriers to resistance and narrow genotypic activity [28]. One NNPI that binds a domain in the polymerase “palm”, dasabuvir, has been approved as a part of a four drug cocktail for GT1, and several other NNPI are in advanced clinical trials (Table 1).

Combating HCV with DAA cocktails

Combining multiple classes of HCV antivirals, as in HIV therapy, raises the overall barrier to resistance and substantially improves SVR rates. 2013 saw the first approval of an all-oral (interferon-free) combination regimen for HCV: the polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir with RBV for GT 2/3 infections. That same year the protease inhibitor simeprevir was approved, and in combination with sofosbuvir provided an all-oral DAA option for GT1. Twelve to 24 week courses of these regimens resulted in SVR rates of 90% or higher for certain populations [32, 33]. In 2014, the FDA approved the first fixed-dose single tablet DAA regimen of sofosbuvir with the NS5A inhibitor ledipasvir for GT1, boosting SVR rates to over 95% even in individuals with prior treatment experience [34, 35]. Just months later, the all-oral NS5A, protease, and polymerase inhibitor cocktail of ombitasvir + paritaprevir/ritonavir + dasabuvir +/− ribavirin offered another highly effective regimen for GT1 [36]. These DAA regimens also provide options for GT4-6 viruses.

In the interferon era, HCV GT3 viruses were considered among the easier genotypes to treat [13], but in the DAA era SVR rates for GT3 are comparably low, particularly in treatment-experienced patients with cirrhosis [37]. The recently available pan-genotypic NS5A inhibitor daclatasivir, when used in combination with sofosbuvir, now offers an interferon-free DAA options with improved SVR rates for GT3 [38]. To improve activity in difficult-to-treat populations, mitigate the threat of multidrug HCV resistance, and further simplify HCV treatment, future DAA cocktails will likely combine DAAs from multiple classes that each have pan-genotypic activity and higher barriers to resistance. Given the rapidity of DAA development, “living documents” such as the IDSA/AASLD guidelines (www.hcvguidelines.org) that keep pace with newly approved regimens for all HCV genotypes are vital for helping clinicians select therapies for their patients.

Prospects for bringing DAAs to children

As of 2016, phase II/III trials of combination DAAs for children ages 3–17 years chronically infected with GT 1, 2, 3, and 4 are underway, as listed in Table 2. If found to be as safe and effective in children as they are in adults, these regimens will almost assuredly replace interferon-based regimens and significantly alter the approach to treatment of pediatric HCV. Rather than deferring therapy until a particular age or waiting for evidence of significant liver disease, treatment could be given as soon as a diagnosis of chronic hepatitis C were made. That being said, in cases of vertical transmission there may be rationale to defer therapy until age 3 years due to the relatively prolonged capacity of infants and toddlers to spontaneously resolve infection [5, 13].

Table 2.

Clinical trials of DAAs in HCV-infected children ages 3–17 years

| Clinicaltrials.gov | Sponsor | Phase | HCV genotype and agents | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT01701063 | Vertex, Janssen | 1,2 | GT1: telaprevir + Peginterferon alfa-2b + ribavirin | Completed |

| NCT01425190 | Merck | 1 | GT1: boceprevir | Terminated early |

| NCT01590225 | Merck | 3 | GT1: boceprevir + Peginterferon alpha-2b + ribavirin | Withdrawn prior to enrollment |

| NCT02486406 | Abbvie | 3 | GT1: ombitasvir + paritaprevir/ritonavir + dasabuvir +/− ribavirin GT4: ombitasvir + paritaprevir/ritonavir + ribavirin |

Recruiting |

| NCT02249182 | Gilead | 2 | GT1 & 4: ledipasvir + sofosbuvir GT3: ledipasvir + sofosbuvir + ribavirin |

Recruiting |

| NCT02175758 | Gilead | 2 | GT2 & 3: sofosbuvir + ribavirin | Recruiting |

One potential obstacle to rapid widespread dissemination of DAA therapies for children is their high cost, a factor which has already resulted in rationing of DAA therapies for adults to those with advanced liver disease [30]. There is hope that costs will fall due to increasing competition if not public pressure. How pediatric HCV regimens will be priced and how insurance companies will prioritize chronically infected children who have a lifetime of risk if not treated remains to be seen.

A second impediment to delivery of DAA therapies to HCV-infected children is the reality that the vast majority of pediatric HCV infections remain undiagnosed [12]. Improved identification of vertically-infected children will require both better detection of HCV-infected pregnant women [39], possibly through implementation of universal antenatal screening in some locales [40], and more comprehensive efforts to ensure that vertically-exposed infants receive proper testing. Strategic use of electronic medical record systems to track HCV-exposed infants and inclusion of early HCV-RNA PCR (such as at age 2 months) in the testing schema may be means to reduce the number of children who are lost to follow-up without any HCV testing [41]. Increased screening of adolescents with a history of IDU is also needed to ensure that more horizontally-acquired cases are identified. One can hope that imminent availability of highly effective, well-tolerated DAA regimens to cure pediatric HCV infections may provide the impetus to boost public health efforts to identify HCV-infected children.

New prospects to prevent HCV in children

The major routes by which children acquire HCV include vertical transmission, injection drug use, and iatrogenic transmission. Current prevention efforts center on avoiding exposure to the virus. Obstetric interventions such as cesarean section do not appear to prevent vertical transmission [42], though avoidance of invasive fetal monitoring in labor is advised based on associations of its use with increased transmission in observational studies [42]. Drug treatment programs are important for limiting horizontal HCV transmission by IDU, but have failed to curtail a rapid increase in new cases of IDU-related HCV among adolescents in the past decade in the U.S [43]. Standard infection control practices for blood-borne pathogens have largely eliminated iatrogenic acquisition of pediatric HCV in developed nations and have reduced rates in many resource limited-countries, but ongoing iatrogenic transmission remains problematic in numerous endemic regions [44].

Interestingly, DAA therapies may offer a powerful new tool to prevent pediatric HCV infections. Widespread distribution of potent and well-tolerated regimens could prevent new HCV infections by reducing the pool of infectious individuals. Nevertheless, several challenges face this “treatment-as-prevention” approach, including the need to convince payers and providers to offer very costly treatment to individuals most likely to transmit the infection (and most susceptible to re-infection) such as active IDU [45]. In endemic nations with infection control lapses that allow ongoing iatrogenic transmission of HCV, major funding and infrastructure issues must be addressed to identify and treat sufficient numbers of HCV-infected individuals to reduce the incidence of new infections [19, 46].

With their improved safety profile, DAAs may be particularly suited for preventing pediatric HCV acquired by vertical transmission. Important regimens including sofosbuvir + ledipasvir and ombitasvir + paritaprevir/ritonavir + dasabuvir appear safe in animal reproduction studies and have earned FDA category B ratings in pregnancy, a marked contrast from the teratogenic properties of ribavirin (category X) that precluded use of pegIFNα/RBV in women during and 6 months prior to pregnancy [47]. These favorable pregnancy safety ratings for DAAs have raised interest in using them to treat pregnant women to prevent vertical transmission [7], analogous to use of antiretroviral therapy to prevent perinatal HIV transmission. However, these regimens have not yet been tested in human pregnancies, and important distinctions between HCV and HIV warrant consideration. Besides the lower transmission rate for HCV [48], vertically acquired HCV is not imminently dangerous for infected children and will likely be easily curable with DAAs. Thus the “reward” for preventing HCV vertical transmission is significantly less than the reward for preventing HIV and arguably HBV vertical transmission. Large studies confirming safety and efficacy of DAAs in pregnancy will be necessary to justify their use in pregnancy over identifying and treating the 5% of children who acquire HCV from their mothers [3, 48]. One approach would be to test DAAs in pregnant women at highest risk of transmitting HCV to their offspring. Higher levels of viremia have generally been associated with a greater risk of transmission, but considerable overlap exists between viral loads of transmitting and non-transmitting mothers [49]. Maternal HIV co-infection was previously linked to a 2–4 fold increased risk of HCV vertical transmission [48], but recent evidence suggests that HIV co-infected mothers who are well controlled on highly-active antiretroviral therapy may be no more likely to transmit HCV than HIV-negative mothers [50, 51]. Thus, more work is needed to clarify which women are at the greatest risk of transmitting HCV and potential candidates for interventional trials to limit HCV vertical transmission [23]. An ongoing large trial by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network may prove useful in this regard. While the potential role of DAA therapy in pregnancy remains to be determined, an alternative prevention approach that is already available is to provide DAA treatment to HCV-infected women of childbearing age who wish to get pregnant in the future. This approach both cures maternal infection and prevents future vertical transmission events and is already advocated in current HCV treatment guidelines (www.hcvguidelines.org).

Finally, it is important to note that the first ever efficacy trial of a preventative HCV vaccine is currently underway, testing the ability of a T-cell based vaccine approach [52] to promote resolution of acute HCV infections in adults who inject drugs (NCT01436357). This vaccine, if successful, may first be utilized in select populations such as health care workers, uninfected IDU, or IDU who have been cured of HCV [53], before expansion to broader at-risk populations [46]. It is not clear how an HCV vaccine would be applied to children or whether it could prevent vertical transmission of HCV. The protective effect of newborn vaccination might be limited given that at least one-third of HCV vertical transmission events appear to occur in utero rather than peripartum [54]. Further, the HCV vaccine currently in clinical trials employs replication-defective chimpanzee adenovirus and vaccinia vectors that have do not yet appear to have been vetted for use in newborn humans [52]. The relatively low rate of vertical transmission and potential to use DAA therapies to prevent or manage vertical transmission could limit initial enthusiasm for a trial of HCV vaccination in newborns. Nevertheless, a comprehensive prevention strategy coupling broad immunization of children at risk for HCV with the DAA “treatment-as-prevention” approach will likely be required to achieve the ultimate goal of eliminating hepatitis C [46].

Conclusion

Though liver disease typically progresses slowly in HCV-infected children, treatment is warranted to avert the risk of advanced liver disease and prevent transmission to others. Combined pegylated interferon-α/ribavirin remains the best approved therapy for pediatric HCV in 2016 but has significant toxicity and fails to cure almost half of children infected with the most prevalent genotype. Advances in drug development have recently provided a host of highly effective antivirals targeting multiple steps in the HCV life cycle. Several well-tolerated combinations of DAAs are now approved for use in adults and have entered clinical trials for children. The first pediatric all-oral DAA trial may be completed as early as 2017 (NCT02249182). Families and providers caring for HCV-infected children anxiously await results of these studies and the opportunity to offer better therapies to children. Potent DAA therapies may also prove useful for preventing pediatric HCV infections if provided to women of child-bearing age and other individuals likely to transmit the virus to children. Realization of the ultimate goal to eliminate pediatric HCV locally and globally will likely require both enhanced efforts to identify HCV-infected individuals for DAA therapy and broad use of an effective HCV vaccine.

Key points.

Pediatric HCV infection remains a major global health threat.

Combinations of potent and well-tolerated DAAs targeting the HCV protease, polymerase, and NS5A are now preferred for treatment of HCV in adults and have entered clinical trials in children.

If proven safe and effective in pediatric trials, DAAs will likely replace interferon-based therapies for HCV-infected children.

Strategic use of DAAs could eventually help reduce new pediatric HCV infections.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs. Zongdi Feng and Christopher Walker for their helpful review of our manuscript.

Financial support and sponsorship:

This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (R01-AI096882 to J.R.H. and The Ohio State University CTSA grant UL1TR001070) and the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital.

Abbreviations

- DAA

direct acting antiviral

- GT

genotype

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- IDU

injection drug use

- NNPI

non-nucleotide polymerase inhibitors

- NS

non-structural

- NPI

nucleotide polymerase inhibitors

- pegIFNα

pegylated interferon-alpha

- RBV

ribavirin

- SVR

sustained virologic response

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:

J.R.H. has received consulting fees from Novartis and is a site-investigator for pediatric trials of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir. S.O. has no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gower E, et al. Global epidemiology and genotype distribution of the hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Messina JP, et al. Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology. 2015;61(1):77–87. doi: 10.1002/hep.27259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3•.Mack CL, et al. NASPGHAN practice guidelines: Diagnosis and management of hepatitis C infection in infants, children, and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54(6):838–55. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318258328d. This practice guideline includes a useful review of the natural history, diagnosis, and currently available therapies for pediatric HCV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Paediatric Hepatitis CVN. Three broad modalities in the natural history of vertically acquired hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(1):45–51. doi: 10.1086/430601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garazzino S, et al. Natural history of vertically acquired HCV infection and associated autoimmune phenomena. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173(8):1025–31. doi: 10.1007/s00431-014-2286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westbrook RH, Dusheiko G. Natural history of hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2014;61(1 Suppl):S58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7•.Jhaveri R, Swamy GK. Hepatitis C Virus in Pregnancy and Early Childhood: Current Understanding and Knowledge Deficits. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2014;3(Suppl 1):S13–S18. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piu045. This review includes useful discussions on the clinical features and pathogenesis of HCV vertical transmission and natural history in infants. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guido M, et al. Fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C acquired in infancy: is it only a matter of time? Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(3):660–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray KF, et al. Liver histology and alanine aminotransferase levels in children and adults with chronic hepatitis C infection. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41(5):634–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000179758.82919.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohan P, et al. Clinical spectrum and histopathologic features of chronic hepatitis C infection in children. J Pediatr. 2007;150(2):168–74. 174, e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson WA, et al. Symptomatic and pathophysiologic predictors of hepatitis C virus progression in pediatric patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(8):724–7. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31819f1f71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12•.Delgado-Borrego A, et al. Expected and actual case ascertainment and treatment rates for children infected with hepatitis C in Florida and the United States: epidemiologic evidence from statewide and nationwide surveys. J Pediatr. 2012;161(5):915–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.05.002. Though now 3 years old, this epidemiologic study provides an important analysis on the extent to which children with HCV remain undiagnosed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wirth S. Current treatment options and response rates in children with chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(2):99–104. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14•.El Sherbini A, Mostafa S, Ali E. Systematic review with meta-analysis: comparison between therapeutic regimens for paediatric chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42(1):12–9. doi: 10.1111/apt.13221. This meta-analysis summarizes the efficacy of interferon based therapies for pediatric HCV due to genotypes 1, 2, and 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15••.Baker RD, Baker SS. Hepatitis C in children in times of change. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27(5):614–8. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000259. This review of pediatric HCV outlines factors to consider in the decision to defer treatment for infected children in this era when better therapies will very likely soon be available. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lohmann V, et al. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science. 1999;285(5424):110–3. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartosch B, Dubuisson J, Cosset FL. Infectious hepatitis C virus pseudo-particles containing functional E1–E2 envelope protein complexes. J Exp Med. 2003;197(5):633–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wakita T, et al. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nature medicine. 2005;11(7):791–6. doi: 10.1038/nm1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19••.Pawlotsky JM, et al. From non-A, non-B hepatitis to hepatitis C virus cure. J Hepatol. 2015;62(1 Suppl):S87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.006. This review provides a big-picture overview of the history of HCV therapies. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20•.Scheel TK, Rice CM. Understanding the hepatitis C virus life cycle paves the way for highly effective therapies. Nat Med. 2013;19(7):837–49. doi: 10.1038/nm.3248. This is an excellent review for the pediatrician seeking a more detailed understanding of mechanisms of HCV replication and origins of the various classes of direct acting antiviral therapies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pawlotsky JM. What are the pros and cons of the use of host-targeted agents against hepatitis C? Antiviral Res. 2014;105:22–5. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowe IA, et al. Effect of scavenger receptor BI antagonist ITX5061 in patients with hepatitis C virus infection undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2015 doi: 10.1002/lt.24349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt WN, et al. Direct-acting antiviral agents and the path to interferon independence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):728–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welsch C, et al. Hepatitis C virus variants resistant to macrocyclic NS3-4A inhibitors subvert IFN-beta induction by efficient MAVS cleavage. J Hepatol. 2015;62(4):779–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horner SM, Gale M., Jr Regulation of hepatic innate immunity by hepatitis C virus. Nat Med. 2013;19(7):879–88. doi: 10.1038/nm.3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poordad F, et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(13):1195–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobson IM, et al. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(25):2405–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Luca A, Bianco C, Rossetti B. Treatment of HCV infection with the novel NS3/4A protease inhibitors. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2014;18:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kieffer TL, George S. Resistance to hepatitis C virus protease inhibitors. Curr Opin Virol. 2014;8:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarrazin C. The importance of resistance to direct antiviral drugs in HCV infection in clinical practice. J Hepatol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eltahla AA, et al. Inhibitors of the Hepatitis C Virus Polymerase; Mode of Action and Resistance. Viruses. 2015;7(10):5206–24. doi: 10.3390/v7102868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32•.Zeuzem S, et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin in HCV genotypes 2 and 3. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(21):1993–2001. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1316145. This is a study of the first all-oral interferon-free option for treating HCV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawitz E, et al. Simeprevir plus sofosbuvir, with or without ribavirin, to treat chronic infection with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 in non-responders to pegylated interferon and ribavirin and treatment-naive patients: the COSMOS randomised study. Lancet. 2014;384(9956):1756–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34••.Afdhal N, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(20):1889–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402454. This is a landmark study of an all-oral option for HCV that is now in clinical trials in children. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Afdhal N, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(16):1483–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1316366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36••.Ferenci P, et al. ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with or without ribavirin for HCV. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(21):1983–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402338. This is a landmark study of an all-oral option for HCV that is now in clinical trials in children. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foster GR, et al. Efficacy of Sofosbuvir Plus Ribavirin With or Without Peginterferon-Alfa in Patients With Hepatitis C Virus Genotype 3 Infection and Treatment-Experienced Patients With Cirrhosis and Hepatitis C Virus Genotype 2 Infection. Gastroenterology. 2015 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson DR, et al. All-oral 12-week treatment with daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 3 infection: ALLY-3 phase III study. Hepatology. 2015;61(4):1127–35. doi: 10.1002/hep.27726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prasad MR, Honegger JR. Hepatitis C virus in pregnancy. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30(2):149–59. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1334459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Selvapatt N, et al. Is antenatal screening for hepatitis C virus cost-effective? A decade’s experience at a London centre. J Hepatol. 2015;63(4):797–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41•.Abughali N, et al. Interventions using electronic medical records improve follow up of infants born to hepatitis C virus infected mothers. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(4):376–80. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000129. This study highlights interventions that may help improve the diagnosis of pediatric HCV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cottrell EB, et al. Reducing risk for mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus:a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-2-201301150-00575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43•.Suryaprasad AG, et al. Emerging epidemic of hepatitis C virus infections among young nonurban persons who inject drugs in the United States, 2006–2012. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(10):1411–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu643. This important epidemiologic paper highlights the rising number of HCV infections in young IDU in the U.S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thursz M, Fontanet A. HCV transmission in industrialized countries and resource-constrained areas. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11(1):28–35. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin NK, et al. Hepatitis C virus treatment for prevention among people who inject drugs: Modeling treatment scale-up in the age of direct-acting antivirals. Hepatology. 2013;58(5):1598–609. doi: 10.1002/hep.26431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cox AL. MEDICINE. Global control of hepatitis C virus. Science. 2015;349(6250):790–1. doi: 10.1126/science.aad1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roberts SS, et al. The Ribavirin Pregnancy Registry: Findings after 5 years of enrollment, 2003–2009. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2010;88(7):551–9. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48•.Benova L, et al. Vertical transmission of hepatitis C virus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(6):765–73. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu447. This is the most recent meta-analysis to estimate the rate of HCV vertical transmission. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Indolfi G, Azzari C, Resti M. Perinatal transmission of hepatitis C virus. J Pediatr. 2013;163(6):1549–1552 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Checa Cabot CA, et al. Mother-to-Child Transmission of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Among HIV/HCV-Coinfected Women. Journal of the pediatric infectious diseases society. 2013;2(2):126–135. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pis091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.A significant sex--but not elective cesarean section--effect on mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(11):1872–9. doi: 10.1086/497695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swadling L, et al. A human vaccine strategy based on chimpanzee adenoviral and MVA vectors that primes, boosts, and sustains functional HCV-specific T cell memory. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(261):261ra153. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Honegger JR, Zhou Y, Walker CM. Will there be a vaccine to prevent HCV infection? Semin Liver Dis. 2014;34(1):79–88. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1371081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mok J, et al. When does mother to child transmission of hepatitis C virus occur? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90(2):F156–60. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.059436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]