Abstract

Scholarship in the area of group identity has expanded our understanding of how group consciousness and linked fate operate among racial and ethnic minority populations in the United States. What is yet to be tested is whether the measures employed adequately capture the multi-dimensional theoretical constructs associated with group consciousness across racial and ethnic populations. To address this question we make use of the 2004 National Political Study (n=3,339) and apply principle components analysis and exploratory factor analysis to assess whether measures used for both group consciousness and linked fate are interchangeable, as well as whether these measures are directly comparable across racial and ethnic populations. We find that the multidimensional approach to measuring group consciousness is a sound strategy when applied to African Americans, as the dimensions fit the African American experience more powerfully than is the case for Non-Hispanic Whites, Hispanics, and Asian populations. Our analysis suggests that scholars interesting in exploring group identity among the African-African population have fewer analytical concerns in this regard than those working with other populations where the underlying components associated with group consciousness appear to be operating differently.

Keywords: Group Consciousness, Group Identity, Linked Fate, Race, Ethnicity, and Politics

Introduction

Although group identity has been a concept of interest to social scientists for some time (Gurin, Miller, & Gurin, 1980; Miller et al., 1981; Olsen, 1970; Verba & Nie, 1972; Shingles 1981), scholars have recently expanded our understanding of how group consciousness and linked fate operate among racial and ethnic minority populations. Scholars interested in group identity have for example found that a sense of commonality and shared circumstances encourages groups to become involved politically (Stokes-Brown 2003; Sanchez 2006a; Chong 2005; Dawson, 1994), partially explaining relatively high rates of political participation among some disadvantaged groups. Although this recent research has greatly improved our understanding of how group identity is formed across racial and ethnic groups, several important research questions remain unanswered. Most notably, research in this area has yet to adequately test whether the measures employed by scholars working in this area adequately capture the theoretical construct of group consciousness, a concept defined by many as multi-dimensional in nature (Miller et al. 1981). Furthermore, largely due to data limitations, research in this area has not been able to directly test whether the measures of group consciousness and linked fate are surrogates for one another or if they are distinct concepts that should not be utilized interchangeably.

We intend to shed some light on these matters through a comprehensive analysis of the concepts of group consciousness and linked fate. More specifically, our research design focuses on whether the survey questions often used to measure group consciousness from a multidimensional perspective actually account for the latent concept of group identity, as well as whether linked fate and the dimensions of group consciousness are highly correlated with one another. We take advantage of the National Political Study (2004) for our analysis which is an ideal dataset for our study, as this dataset contains measures of both linked fate and multiple dimensions of group consciousness, as well as a robust sample of multiple racial and ethnic populations. The wide sample across populations is vital, as this allows our analysis to include an assessment of whether these questions of measurement vary by race/ethnicity. Racial and ethnic group identity is a complex construct, made up of multiple intersecting and interacting dimensions. In addition to variation in identity formation between racial and ethnic groups based on distinct histories and treatment in the U.S., substantial variation in group identity exists within groups. In this paper we leverage both between-group and within-group variation to explore the complexity of politicized group identities among survey respondents identifying as African American/Black, Asian American, Hispanic/Latino, and Non-Hispanic White.

Defining Group Consciousness

Scholars interested in the political implications of group identity have applied the concept of group consciousness to many political outcomes over time finding evidence that the concept leads to increased political engagement for racial and ethnic groups. Theories based on Verba and Nie’s (1972) application of group consciousness in their larger model of political participation has been widely used to explain political behavior among minority groups. Specifically, scholars have suggested that group consciousness leads to increased political participation (Miller et al. 1981; Stokes-Brown 2003; Sanchez 2006a; Tate 1994), greater support for coalitions with other racial/ethnic groups (J. Garcia 2000; Kaufmann 2003; Sanchez 2008; Uhlaner 1991), and more liberal views toward many public policies (Dawson 1994; Hochschild 1995; Sanchez 2006b) among minority groups. Furthermore, many have argued that group consciousness is a political resource that can help explain relatively high political participation rates among some disadvantaged groups (Leighley 2001; Olson 1965; Verba and Nie 1972). Finally, scholars have also suggested that group consciousness influences the behavior of political elites (Rocca and Sanchez 2009; Morin 2014; de la Garza and Vaughn 1984). Group consciousness is therefore a rather powerful concept that has relevance to scholars across many sub-fields within political science.

Group consciousness is defined as a politicized in-group identification based on a set of ideological beliefs about one’s group’s social standing, as well as a view that collective action is the best means by which the group can improve its status and realize its interests ( Jackman & Jackman 1973, Gurin et al. 1980, Miller et al. 1981), Further, as Miller et al. (1981) posit, group consciousness among racial and ethnic groups must encompass both group identification and the perception that the group’s lower status1 could be remedied by increased collective action. These definitions imply that the concept is a multi-dimensional one with three distinct components: group identity, recognition of disadvantaged status, and desire for collective action to overcome that status (Garcia 2003; Miller et al. 1981).

Unfortunately, there has not been a consistent measurement strategy employed by scholars in this area. For example, some scholars have utilized only one measure, such as a sense of commonality within groups (Masuoka 2006; Olson 1965; Verba and Nie 1972). Uhlaner (1989) measured group consciousness using membership in American ethnic or non-ethnic organizations and social groups, an interesting yet unique approach relative to other work in the area. Similarly, although also constricting measurement of group consciousness to one dimension, Masuoka (2004) uses a measure of perceived Latino collective action to assess the concept. Olsen (1970) focused on African Americans who had identified themselves as members of an ethnic minority versus those who did not. Verba and Nie (1972) used an index that summed the number of times African American respondents referred to race in responses to several open-ended questions. These authors not only focused their measurement on only one aspect of the concept of group consciousness, but used different approaches in their effort to measure the concept.

Others have come much closer to accounting for multi-dimensionality of the concept by including a measure for each dimension of group consciousness suggested by Miller et al. 1981 (see Sanchez 2006a, 2006b; Lien 1994 and Stokes-Brown 2003 for examples). However, even here there remains some variation in approach to capturing dimensions of the concept. For example, while there appears to be consistency in the use of discrimination to assess the second dimension of group consciousness, some studies use a perceived group discrimination question while others utilize a personal measure of experiences with discrimination. While the current study will not resolve all issues associated with conflicting measurement approaches in this literature, it will provide some insights that should help scholars standardize measurement approaches moving forward.

The next logical step in the progression of the measurement of group consciousness is to use more appropriate multi-dimensional methodological techniques to assess whether the three measures of group consciousness employed by scholars are actually capturing the same latent components of group identity described in the literature. To our knowledge this has not been done by scholars of group identity. We take this one step further by using principle component and exploratory factor analysis to test if there are similar underlying dimensions in group consciousness across racial and ethnic groups. This we argue could be the more appropriate measurement strategy for the important concept of group consciousness due to its ability to achieve parsimony (McClain et al. 2009) while maintaining the multi-dimensional nature of the concept.

Defining the Concept of Linked Fate

A related form of group identity that has been particularly useful in describing the persistent use of group-based cues by racial and ethnic groups is the concept of linked fate. Theories of linked fate suggest that given the centrality of racial stratification in the US, minority political beliefs and their actions as individuals are related to their perceptions of racial group interests (Tate 1994; Dawson 1994; McClain et al. 2009). According to Dawson (1994), African Americans who perceive their individual fates to be tied to those of their racial group are more likely to rely on group-based interests when they make political decisions. Linked fate has been identified as an explanation for why, despite increasing economic polarization, African Americans remain a relatively cohesive political group (Dawson 1994; Hochschild 1992).

While some scholars of racial and ethnic group politics have critiqued the concept of linked fate as being one-dimensional (Simien 2006; Prince 2009; Beltran 2010), we make use of the concept to explore the extent to which it is empirically the same or different than the more explicitly multi-dimensional concept of group consciousness. The measurement approaches for linked fate among scholars has been more consistent relative to group consciousness. That said, there is a slight difference in the measurement strategy across representative studies. For example, the Latino National Survey’s (LNS), asks respondents : How much does your “doing well” depend on other Latinos/Hispanics also doing well as opposed to what is asked in the National Black Election Study: Do you think that what happens to [R Race] people in this country will have something to do with what happens in your life? Our measure of linked fate is consistent with the latter approach, and more importantly, our data source provides the ability to have a consistent measure applied to multiple racial and ethnic groups, as well as to directly compare linked fate to group consciousness, two major advantages for the purposes of our analysis relative to other data-sets.

Variation of Group Identity Across and Within Groups

Although the linked fate measure was originally constructed based on the specific experiences of African Americans, recent work suggests that linked fate is present within pan-ethnic communities as well. Masuoka (2006) finds that linked fate is meaningful for a large segment of the Asian American community. Further, Lien, Conway, and Wong’s (2004) examination of the National Asian American Political Survey found that linked fate is not only present among Asian Americans, but also increases political participation for this group. Furthermore, Masuoka and Sanchez’s (2010) analysis of the Latino National Survey (Fraga et al. 2006) reveals that a large segment of the Latino community perceives that their individual fate is not only linked to other Latinos, but that the status of their national origin group is also tied to that of Latinos more generally. Finally, Barreto, Masuoka and Sanchez (2009) find relatively high levels linked fate among the Muslim American population motivated by shared discrimination experiences and religiosity.

This new research suggests the emergence of linked fate in racial and ethnic communities beyond the African American population. That said, McClain et al. (2009) argue in their review article of the literature associated with group identity that this concept, along with group consciousness, were originally created to fit the experience of African Americans. As such, they contend that scholars should not attempt to force these concepts onto populations other than Blacks. This is reinforced by the work of others who have noted that the concept of linked fate may overlook differences in histories across groups and important internal differences that have implications for group identity, such as gender (Simien 2006), and treatment from/relationships with the US government (Beltran 2010; Lavariega Monforti and Sanchez 2010). This inter-group variation includes differential access to citizenship, arguably the greatest indicator of acceptance within a society, as well as national origin and nativity. Scholars of Latino and Asian American politics have emphasized the need to account for national origin, citizenship, and nativity within these pan-ethnic populations when exploring group identity for some time (Masuoka and Sanchez 2010; Beltran 2010; Junn and Masuoka 2008; Fraga et al. 2012). However, new research has found the need to account for differences in country of origin among Blacks as well. Christina Greer, for example, identifies meaningful differences in how Afro-Caribbean and African immigrant Blacks are viewed by Whites compared to African Americans (Greer 2013), with Smith (2014) finding that this important difference has direct implications for racial identity among Blacks.

Racial and ethnic group identity is a complex construct, made up of multiple intersecting and interacting dimensions. In addition to variation in identity formation between racial and ethnic groups based on distinct histories and treatment in the U.S., substantial variation in-group identity exists within groups due to cultural factors such as national origin and language use. In this paper we leverage the ability to examine both between-group and within-group variation to explore the complexity of politicized group identities among survey respondents identifying as African American/Black, Asian American, Hispanic/Latino, and Non-Hispanic White.

More specifically, given that we utilize a unique dataset that allows for direct comparisons of group consciousness and linked fate across groups, we assess whether African Americans do in fact have higher levels of politicized group identity than other racial and ethnic groups through both descriptive statistics and comparison of means tests. Furthermore, in our approach to gauging the effectiveness of the three measures of group consciousness to capture the dimensions of the concept, we run separate analyses for each racial and ethnic group available in our data: African Americans, Latinos, Whites, and Asian Americans. This will allow for an assessment of whether the measures of group consciousness commonly employed by scholars do a better job of accounting for the variance in this concept for one group relative to another.

Although the primary focus of this analysis is not to assess factors that yield higher levels of group identity across groups, we stratify our sample by citizenship status, acculturation, and national origin to ensure that our analysis takes into consideration the important variation within these communities. Although scholars have found group identity to be meaningful across multiple racial and ethnic groups, there is evidence to suggest that group consciousness and linked fate may operate differently across racial and ethnic groups, as might be expected given the distinct histories and treatment of different racial and ethnic groups in the U.S. In regard to linked fate, it appears as though the contributing factors to this form of group identity may vary greatly by racial/ethnic group. Shared race along with a shared history of unequal treatment in the U.S. serves as the basis for linked fate among African Americans (Dawson 1994) and, to some extent, Asians (Masuoka 2006). However, factors associated with the immigration experience, such as nativity and language preference, appear to be the basis for Latino linked fate, with the less assimilated holding stronger perceptions of common fate with other Latinos (Masuoka and Sanchez 2010). Furthermore, despite discrimination serving as the foundation for linked fate among African Americans (see Dawson 1994), Masuoka and Sanchez (2010) find that discrimination is not a contributor to linked fate through their analysis utilizing the Latino National Survey. We therefore anticipate that the dimensions of group consciousness will perform better as measures for the concept when applied to African Americans relative to other groups. We approach this analysis from the standpoint that both forms of group identity will operate similarly for Latinos and African Americans however, with the concepts being a weaker fit for the Asian and White Americans. Although different than the experiences of African Americans, Latinos have experienced a long history of discriminatory practices including segregation, and exclusionary practices in the U.S. (Kamasaki, 1998; Lavariega Monforti & Sanchez, 2010; Massey & Denton, 1989) which we believe could lead to some similarity between these two groups in terms of measures of politicized group identity. We therefore hypothesize that the Asian American and non-Hispanic White communities will prove to show distinct patterns from those of Latinos and African Americans.

Distinction between Linked Fate and Group Consciousness

The final theory that we test in our analysis is whether the concepts of linked fate and group consciousness are in fact distinct or if they can be used as surrogates for one another. This aspect of our analysis is again motivated largely by the contention of McClain et al. (2009) that scholars in this area have not utilized enough discretion in how they treat these two aspects of group identity. More specifically, McClain et al. (2009) suggest that that some scholars have used linked fate as “a sophisticated and parsimonious alternative” to the operationalization of racial group consciousness (pg. 477). Given the complexities associated with the measurement of the multi-dimensional concept of group consciousness outlined here, we can sympathize with the desire to find a single measure to capture what is assumed to be the same construct. In short, we attempt to test this assumption by exploring whether linked fate and group consciousness are in fact interchangeable or if they are inter-connected but empirically distinct concepts. Given the complexity of group identity, made up of multiple intersecting and interacting dimensions, we anticipate that the one-dimensional concept of linked fate will not be a sufficient substitute for the multi-dimensional concept of group consciousness. Our results should provide some helpful insights for scholars working in this area to follow when operationalizing these important concepts.

Data and Methods

To better understand the dimensions of group consciousness across racial and ethnic groups we make use of the 2004 National Politics Study (Jackson et al. 2004). The NPS collected a total of 3,339 interviews using computer assisted telephone interviews (CATI) from September 2004 to February 2005. The NPS collected data on individuals’ political attitudes; beliefs, aspirations, behaviors, as well as items that tap into the dimensions of group consciousness, linked fate, government policy, and party affiliation. The NPS sample consist of 756 African Americans, 919 non-Hispanic Whites, 757 Hispanics, 503 Asians, and 404 Caribbean’s. NPS is unique in that it has a relatively large racial and ethnic group sample with various measures of group consciousness and linked fate, and as the principal investigator’s state, provide the unique opportunity to make direct comparisons across multiple groups: “to our knowledge, this is the first nationally representative, explicitly comparative, simultaneous study of all these ethnic and racial groups.” 2

The primary survey items this analysis uses include group commonality, perceived discrimination, collective action, and linked fate. The first step in this analysis is to summarize and rank each racial and ethnic group by the four items, followed by a series of means differences test for each racial and ethnic group. All means difference test were conducted with a chi-square test, as the chi-square allows us to use categorical variables.

The second step in this analysis is to perform a series of principle component analysis (PCA) and biplots to differentiate items across racial and ethnic samples. Biplots are advantageous here as they allow us to graphically display the correlations between items in a two dimensional space. The goal here is to visually display how the items of group consciousness compare across racial and ethnic groups. PCA is a statistical technique that linearly transforms an original set of variables into a substantially smaller set of uncorrelated variables that represents most of the information in the original set of variables (Jacoby, 1991). PCA has traditionally been used as a data reduction technique to address problems with multicollinearity and inherently allow data analyst to visually display how variables relate to each other. PCA and biplots (which graphically display data) are matrix manipulations which use singular value decomposition (SVD) to uncover the basic (i.e. linear) structure of the matrix using correlations (Jacoby, 1991). In a biplot, the plane is oriented so the sum of squared lengths is maximized. To examine if items are related, we examine the cosines between angles as this represents the correlations between the items, the smaller the angles the greater the correlation. The closer the angle is to 90, or 270 degrees, the smaller the correlation, if an angle is 0 or 180 degrees, this reflects a correlation of 1 or 1, respectively. Regarding length of the arrows, the observations whose points project furthest are the observations with the most varying direction in the data.

The third step of our analysis is to conduct a series of exploratory factor analyses to better understand the underlying dimensions of group consciousness for each racial and ethnic group. Factor analysis allows researchers the ability to understand and untangle complex interrelationships and uncover relationships by separating different sources of variation. This analysis allows us answer three key questions: Do the measures of group consciousness produce the same number of latent factors across racial and ethnic groups? Do the items load similarly across racial and ethnic groups, or do some items drive the effect more than others? Is the relationship between the newly created latent factor (group consciousness) and linked fate orthogonal? 3 In other words, are these measures uncorrelated with one another (by a 90 degree angle in a biplot)? We also include results that compare Asian and Hispanic respondents who are U.S. citizens versus their co-ethnic counterparts who are noncitizens to account for internal variation due to citizenship status for these populations. As a sensitivity analysis, we analyze the impact of being raised in the U.S. for Hispanic and Asian samples as a measure of acculturation as well as include Caribbean’s into the Black label to test the robustness of our findings, which we include in the appendix.

Factor analysis allows us to explain why groups of variables are correlated. For factor analysis to work efficiently, you must work with a correlation matrix and standardized variables. In factor analysis the source variables are unobserved and a factor analytic model is set up such that each factor (F) affects several observed variables (Z). Each Zj also has a unique source of variation Uj that can be thought of as random. With factor analysis, we can estimate the extent to which the factors influence the observed variables (with factor pattern coefficients) and the extent to which the Uj's affect their corresponding observed variables. Unlike PCA, factor analysis has an underlying statistical model that partitions the total variance into common and unique variance and focuses on explaining the common variance, rather than the total variance, in the observed variables on the basis of a relatively few underlying factors. PCA on the other hand is just a mathematical re-expression of the data that maximizes variance.

To estimate the factor analysis in our study that uses ordinal measures an important assumption has to be made. When estimating standard factor analysis based on Pearson’s correlations, we assume the variables are normally distributed and measured as continuous. If however, and you have variables that are dichotomous or ordinal (but not nominal), factor analysis can be performed using a polychoric correlation matrix. Therefore, these analyses are performed using the flexibility of the polychoric correlation matrix as our measures are ordinal. All results of the factor analysis are weighted using the survey’s pweights and factors are rotated using varimax and assumed to be orthogonal.

Results

The following survey items are used in this analysis: group commonality, collective action, perceived discrimination, and linked fate. The coding scheme and survey wording are provided to better illustrate the measurement of each item. As reflected in Table 1, and consistent with extant theory, Blacks have the highest sense of group commonality (perceived commonality with one’s own group) followed by Hispanics, Whites, and then Asians. In regards to statistical significance, results from Chi-square means tests indicate that Blacks commonality with other Blacks and Hispanics commonality with other Hispanics are statistically different than Asians commonality with other Asians (lower commonality), which is significant at the 0.001 confidence level.

Table 1.

Group Consciousness Summary Statistics and Means Test

| Commonality (C): How close do you feel to each of the following groups of people in your ideas, interests, and feeling about each other? 1=Not close at all, 2=Not too close, 3=Fairly close, 4=Very close | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | N | Difference in Means1 | ||||

| Black | 3.398 | 0.733 | 742 | White-C-Whites | Black-C-Blacks | Hisp.-C-Hisp. | |

| Hispanic | 3.383 | 0.734 | 744 | Black-C-Blacks | 0.086 | -- | -- |

| White | 3.308 | 0.626 | 874 | Hispanic-C-Hispanics | 0.073 | −0.014 | -- |

| Asian | 3.23 | 0.725 | 495 | Asian-C-Asians | −0.068 | −0.154*** | −0.140*** |

| Collective Action (CA): It is important for people to work together to improve the position of their racial or ethnic group? 1=Strongly Disagree, 2=Somewhat Disagree, 3=Somewhat Agree, 4=Strongly Agree | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | N | Difference in Means1 | ||||

| Black | 3.803 | 0.51 | 747 | White-CA-Whites | Black-CA-Blacks | Hispanic-CA-Hispanics | |

| Hispanic | 3.666 | 0.645 | 737 | Black-CA-Blacks | 0.151*** | -- | -- |

| Asian | 3.665 | 0.583 | 496 | Hispanic-CA-Hispanics | 0.014 | −0.137*** | -- |

| White | 3.652 | 0.618 | 903 | Asian-CA-Asians | 0.013 | −0.138*** | −0.001 |

| Perceived Discrimination (PD): How much discrimination or unfair treatment you think different groups face in the U.S.? 1=None, 2=A Little, 3=Some, 4= A lot | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | N | Difference in Means1 | ||||

| Black | 3.464 | 0.666 | 752 | White-PD-Whites | Black-PD-Blacks | Hispanic-PD-Hispanics | |

| Hispanic | 3.197 | 0.791 | 746 | Black-PD-Blacks | 1.343*** | -- | -- |

| Asian | 2.719 | 0.706 | 494 | Hispanic-PD-Hispanics | 1.080*** | −0.262*** | -- |

| White | 2.127 | 0.906 | 908 | Asian-PD-Asians | 0.620*** | −0.722*** | −0.460*** |

| Linked Fate(LF): Two Part Question, Question 1. Do you think that what happens to [R Race] people in this country will have something to do with what happens in your life? If Yes, then, Question 2. Will it affect you a lot, some or not very much?0=no (from Q1) , 1=Not Very Much, 2=Some, 3=A lot | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | N | Difference in Means1 | ||||

| Black | 1.632 | 1.242 | 753 | White-LF-Whites | Black-LF-Blacks | Hispanic-LF-Hispanics | |

| Asian | 1.388 | 1.138 | 497 | Black-LF-Blacks | 0.372*** | -- | -- |

| White | 1.26 | 1.171 | 903 | Hispanic-LF-Hispanics | −0.201*** | −0.573*** | -- |

| Hispanic | 1.06 | 1.234 | 755 | Asian-LF-Asians | 0.128 | −0.244*** | 0.329*** |

p<.10,

P<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

The next dimension of group consciousness is collective action or the idea one must work together collectively to improve your own race or ethnic group’s situation. Summary statistics indicate that Blacks have the highest sense of collective action followed by Hispanics, Asians, and then Whites. In regards to statistical significance, results from Chi-square means test indicate suggests that Blacks are the only group to report a higher need to work together to collectively improve the situation of other Blacks, compared to Whites, Asians, and Hispanic respondents, which is significant at the 0.001 confidence level.

Consistent with commonality and collective action, Black respondents report that Black populations face the highest level of discrimination and unfair treatment, followed by Hispanics, Asians, and Whites. In regards to statistical significance, the results from difference in means tests indicate that Blacks perceived discrimination is statistically different than all other racial and ethnic groups. Hispanic respondents report higher levels of perceived discrimination compared to Asian and White respondents, and Asian respondents report higher levels of discrimination compared to White respondents, which are all statistically significant at the 0.001 confidence level.

In sum, African Americans have a greater overall level of group consciousness across these three dimensions, with Latinos trailing slightly. We conclude this aspect of our analysis by providing an assessment of the relative levels of linked fate across groups. We find that similar to group consciousness, Blacks have the highest sense of linked fate, or belief that what happens to them in this country will have something to do with what happens in their own life. Surprisingly, linked fate is higher among Asians and Whites compared to Hispanics respondents. More specifically, difference in means comparisons show that African Americans and Asian Americans are more likely to report higher linked fate than Whites (significant at the 0.001 confidence level), however Blacks have a greater sense of linked fate than Asians (significant at the 0.001 confidence level). Our results indicate that Hispanics have the lowest level of linked fate among groups in this sample, as they are statistically less likely to express a sense of linked fate when compared to all groups, including White and Asian respondents (all significant at the .001 confidence level). This somewhat surprising finding is something we reflect on in our concluding discussion.

In summary, the descriptive statistics and differences in means tests detail the important differences across racial and ethnic groups for three measures of group consciousness (commonality, perceived discrimination, and collective action) and linked fate. In general, Blacks have the highest reported levels on each of these items followed by Latinos, with the exception of linked fate where Latinos have the lowest levels among the groups included in our sample. Finally, Asians generally have higher rates of group identity than Whites who had the lowest levels of group identity when taken collectively.

The next analysis moves from descriptive and means testing to a multidimensional data analysis approach to examine if the measures we use to quantify group identity are in fact measuring the same construct.

Multi-Dimensional Results

The first approach in our analysis is focused on differentiating how these various measures are related to each other through a series of principle component analysis (PCA) and biplots. We then estimate various exploratory factor analyses to understand the underlying factors by race and ethnicity and citizenship status for foreign born Asians and Latino respondents. This analysis will help clarify whether the measures of each dimension of group consciousness identified in the literature are in fact capturing the same latent concept of group identity, as well as whether linked fate and group consciousness are in fact the same concept. The ability to explore this line of inquiry across multiple groups provides the ability to determine if the measures perform more effectively for any particular racial and ethnic group.

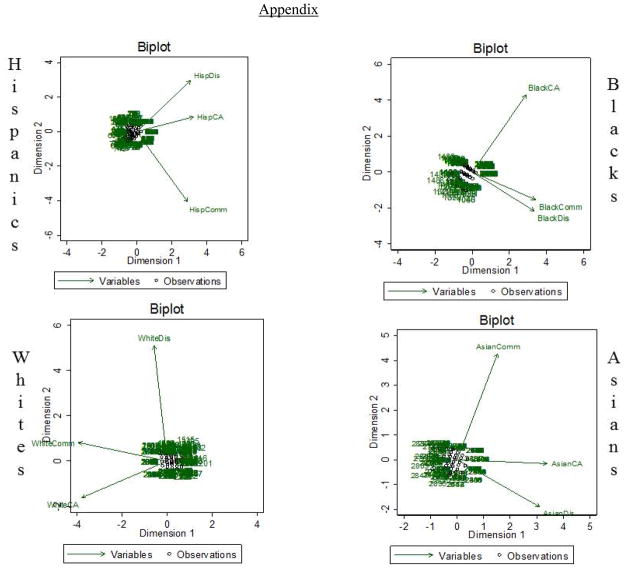

From the biplots depicted in Figure 1, we can visualize the relationship between the three measures of group consciousness across each racial and ethnic group directly. In a biplot, the length of the lines approximates the variances of the variables, with the longer the line equating to higher variance. The angle between the lines, or, the cosine of the angle between the lines, approximates the correlation between the variables they represent. The closer the angle is to 90, or 270 degrees, the smaller the correlation. An angle of 0 or 180 degrees reflects a correlation of 1 or 1, respectively. As shown in these biplots, the measures of group identity do differ across racial and ethnic groups in important ways. For example, for African American respondents, perceived discrimination and Black commonality are highly correlated4. Moreover, given that the discrimination arrow is slightly longer than commonality arrow for Blacks, perceptions of discrimination explains more of the variance relative to Black commonality. For Hispanics and Asian respondents, however, collective action and perceived discrimination are correlated to a greater degree. In summary, the three measures of group identity are not similar across racial and ethnic groups. Moreover, the total variance explained for each biplot is not uniform. For Hispanics, the biplot represents 69.2 percent of the total variance in the data. For Blacks, the biplot represents 73.2 percent, Asians (71.3 percent), Whites (68.8 percent) of the total variance in the data.5 We interpret this to mean that the measures typically employed to measure group identity fit the African American experience more powerfully than is the case for other groups.

Figure 1.

Biplots of Group Identity Items Across Race/Ethnicity

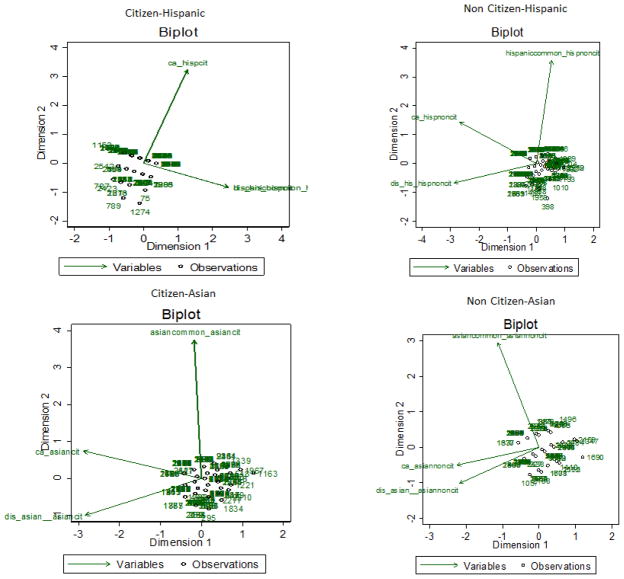

The findings from the biplots indicate that if we differentiate the measures of group identity they are in fact operating differently for Blacks compared to Latinos, Asians, and Whites. Given this distinction we have attempted to explain why this might be occurring with a specific emphasis on whether citizenship status changes the results for Hispanic and Asians? To address this question we separated out Latino and Asian respondents by citizenship status to form four groups, Latino citizens and non-citizens, Asian citizens and non-citizens.

Our investigation of the differences in group identity among Latinos and Asians based on citizenship status reveals some interesting findings. From figure 2, we find that there are differences for citizen and non-citizen Latinos as perceptions of commonality and perceived discrimination are closely related for Latino citizens. However, there is a different pattern among non-citizen Latinos, with perceived discrimination and collective action to be closely related. There is less variation in how the measures of group consciousness relate to each other among Asian Americans, however, as we find the measures of collective action and discrimination are more closely aligned among both groups of this population. 6 Although outside the scope of this article, these results suggest that scholars interested in exploring group identity across the Latino should be sensitive to the nuances associated with how group identity is manifested across differently among Latinos who are and are not US citizens.

Figure 2.

Biplots of Group Identity Items across Citizenship Status

The next step in our analysis is to use an exploratory factor analysis to estimate the number of factors underlying group commonality, perceived discrimination, and collective action. Table 2, provides the output with variance explained, factor loadings, and chi-square goodness of fit statistics. Our results indicate that when combined there is one factor underlying the three measures group consciousness for Black and Hispanic respondents but a two factor solution for White and Asian respondents. This is an important finding that provides some clarity to researchers regarding measurement approaches. We suggest that if estimating a model using group consciousness as an explanatory variable, researchers can combine these three measures into one factor to gain strengths regarding parsimony (such as a scale) for Blacks and Hispanics, but should also include the second factor for Whites and Asians. In terms of model fit, the exploratory factor analysis is strongest for Blacks (chi2(3) = 200.4, prob>chi2 = 0.0000) with the one factor solution explaining 79 percent of the variance. Thus, while this analysis provides some support for our expectation that there would be similarities in measurement fit for Latinos and African Americans given common discrimination experiences for both groups, it is clear that the dimensions of group identity commonly utilized by scholars in the field best fit the African American case.

Table 2.

Exploratory Factor Analysis of Group Identity Items

| Retained Factors | Variance | Proportion | Cumulative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanics n=722 | 1 | 0.222 | 3.584 | 3.584 |

| Rotated Factor Loadings (pattern matrix) and Unique Variances | ||||

| Items: | Factor 1 | Uniqueness | ||

| Commonality | 0.200 | 0.960 | ||

| Perceived Discrimination | 0.315 | 0.901 | ||

| Collective Action | 0.289 | 0.917 | ||

| chi2(3) = 23.01 Prob>chi2 = 0.0000 | ||||

| Retained Factors | Variance | Proportion | Cumulative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blacks n=735 | 1 | 0.789 | 1.710 | 1.710 |

| Rotated Factor Loadings (pattern matrix) and Unique Variances | ||||

| Items: | Factor 1 | Uniqueness | ||

| Commonality | 0.502 | 0.748 | ||

| Perceived Discrimination | 0.536 | 0.713 | ||

| Collective Action | 0.500 | 0.750 | ||

| chi2(3) = 200.41 Prob>chi2 = 0.0000 | ||||

| Retained Factors | Variance | Proportion | Cumulative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asians n=480 | 1 | 0.119 | 1.987 | 1.987 |

| 2 | 0.087 | 1.454 | 3.441 | |

| Rotated Factor Loadings (pattern matrix) and Unique Variances | ||||

| Items: | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Uniqueness | |

| Commonality | 0.102 | 0.165 | 0.962 | |

| Perceived Discrimination | 0.223 | 0.131 | 0.933 | |

| Collective Action | 0.243 | 0.207 | 0.898 | |

| chi2(3) = 14.49 Prob>chi2 = 0.0023 | ||||

| Retained Factors | Variance | Proportion | Cumulative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whites n=854 | 1 | 0.059 | 6.256 | 6.256 |

| 2 | 0.016 | 1.648 | 7.904 | |

| Rotated Factor Loadings (pattern matrix) and Unique Variances | ||||

| Items: | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Uniqueness | |

| Commonality | 0.172 | 0.085 | 0.963 | |

| Perceived Discrimination | 0.028 | 0.071 | 0.994 | |

| Collective Action | 0.171 | 0.060 | 0.967 | |

| chi2(3) = 4.05 Prob>chi2 = 0.2558 | ||||

The next step in our analysis is to explain the majority of the variance for the retained factor? In other words what item is driving the effect in the retained group identity latent variable? The rotated factor loadings and pattern matrix are provided in Table 2 and allow us to understand how variables are weighted for each factor and the correlation between the variables and the latent factor. For Latinos and Blacks, the individual item that is driving the relationship is perceived discrimination (Hispanics=32 percent, Blacks=54 percent). We visually saw this relationship with the biplots in Figure 1, as perceived discrimination and commonality are more closely aligned (cosines were smaller) for African Americans, and perceived discrimination and collective action are more closely aligned for Hispanics. This provides support to our theory regarding similarities between Latinos and Blacks, as perceived discrimination is the driving force within group consciousness for these two populations. For Asian populations, the leading item that drives the first factor is collective action and for White respondents, commonality drives the first factor solution.

We now turn our attention to the next and arguably most important question, how does linked fate compare to the measures of group consciousness we have discussed in the previous section? Using exploratory factor analysis we include linked fate as a fourth measure of group identity along the three dimension of group consciousness. From Table 3, we find that only Blacks retained a one factor solution with the four items, with perceived discrimination continuing to explain the majority of the variance in the retained factor (60 percent)7. This suggests that linked fate and group identity are highly connected for the African American population, with discrimination serving as a major motivator for both forms group identity. While we are hesitant to suggest that these measures are interchangeable with each other for African Americans, our analysis suggests that there is less cause for concern regarding using aspects of both (or all components) in group identity scales when conducing research specific to this group. The powerful role of perceived discrimination in this analysis supports the work of Dawson (1994) and others who have suggested that discrimination is the driving force behind group identity for Blacks.

Table 3.

Exploratory Factor Analysis of Group Identity Items and Linked Fate

| Retained Factors | Variance | Proportion | Cumulative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanics n=721 | 1 | 0.266 | 1.092 | 1.092 |

| 2 | 0.256 | 1.048 | 2.140 | |

| Rotated Factor Loadings (pattern matrix) and Unique Variances | ||||

| Items: | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Uniqueness | |

| Commonality | 0.156 | 0.243 | 0.917 | |

| Perceived Discrimination | 0.312 | 0.264 | 0.833 | |

| Collective Action | 0.227 | 0.144 | 0.928 | |

| Linked Fate | 0.305 | 0.326 | 0.801 | |

| chi2(6) = 96.05 Prob>chi2 = 0.0000 | ||||

| Retained Factors | Variance | Proportion | Cumulative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blacks n=733 | 1 | 1.139 | 1.502 | 1.502 |

| Rotated Factor Loadings (pattern matrix) and Unique Variances | ||||

| Items: | Factor 1 | Uniqueness | ||

| Commonality | 0.490 | 0.760 | ||

| Perceived Discrimination | 0.604 | 0.635 | ||

| Collective Action | 0.500 | 0.750 | ||

| Linked Fate | 0.533 | 0.717 | ||

| chi2(6) = 355.77 Prob>chi2 = 0.0000 | ||||

| Retained Factors | Variance | Proportion | Cumulative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asians n=478 | 1 | 0.402 | 1.443 | 1.443 |

| 2 | 0.218 | 0.782 | 2.225 | |

| Rotated Factor Loadings (pattern matrix) and Unique Variances | ||||

| Items: | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Uniqueness | |

| Commonality | 0.443 | 0.067 | 0.800 | |

| Perceived Discrimination | 0.050 | 0.315 | 0.898 | |

| Collective Action | 0.104 | 0.298 | 0.901 | |

| Linked Fate | 0.439 | 0.159 | 0.782 | |

| chi2(6) = 70.21 Prob>chi2 = 0.0000 | ||||

| Retained Factors | Variance | Proportion | Cumulative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whites n=842 | 1 | 0.306 | 2.438 | 2.438 |

| 2 | 0.042 | 0.333 | 2.771 | |

| Rotated Factor Loadings (pattern matrix) and Unique Variances | ||||

| Items: | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Uniqueness | |

| Commonality | 0.356 | 0.116 | 0.860 | |

| Perceived Discrimination | 0.017 | 0.126 | 0.984 | |

| Collective Action | 0.209 | −0.016 | 0.956 | |

| Linked Fate | 0.367 | 0.110 | 0.853 | |

| chi2(6) = 55.13 Prob>chi2 = 0.0000 | ||||

Alternatively, Latinos, Asians, and Whites all retained a two factor solution when linked fate is added to the dimensions of group identity. For Hispanics, perceived discrimination explained the majority of the variation in factor 1, it is indeed linked fate that explains the majority of the variance in factor 2. Substantively, what these findings suggest is that for Blacks: collective action, commonality, perceived discrimination and linked fate are all tapping into the same general construct (i.e. group identity). For Hispanics, Asians, and Whites, these items are tapping into two distinctive constructs, suggesting that linked fate and group consciousness are definitely not inter-changeable constructs when applied to these groups. Taking a closer look at the output, we can see that for Latinos the two driving forces for these distinctive factors are perceived discrimination and linked fate and for Blacks perceived discrimination is explaining the majority of the variance in the retained factor.

Conclusions

Group identity has and will continue to be a central concept to social scientists generally, and particularly political scientists interested in political behavior. Consequently, it is vital for researchers to ensure that the measures we employ for analysis actually match the theoretical concepts themselves, and apply them appropriately across racial and ethnic populations. This paper is to our knowledge the first to directly compare levels of both group consciousness and linked fate across multiple racial and ethnic groups, as well as the first to test whether the measures commonly employed for linked fate and group consciousness are capturing the same general construct when applied across these populations.

In short, we find that African Americans are the population who have the highest levels of both group consciousness and linked fate, which is consistent with our collective knowledge of these concepts. Furthermore, we find that the three dominant dimensions of group consciousness fit the African American experience more powerfully than is the case for other groups. This same general pattern holds when we include linked fate into this analysis, where there is a high correlation between the two measures of group identity within the African American case. Our analysis therefore suggests that scholars interested in exploring group identity among African Americans have fewer analytical concerns in this regard than those working with other populations where there are significant differences between the underlying factors associated with these concepts.

We theorized that due to shared experiences with discrimination we would see similar patterns across group identity for Latinos and African Americans relative to Whites and Asians. While we have summarized the important differences between these two groups, we do find some support for this theory across our analysis. For example, the three dimensions of group consciousness typically used by researchers utilizing a multidimensional approach with measurement load onto one factor for both Latinos and African Americans. This implies that creating a single measure based on these dimensions to capture group consciousness is justifiable for these two groups, less so for Asian Americans or Whites. We also find that perceived discrimination is a driving force for group identity for both Latinos and African Americans, supporting the work of scholars who have theorized that discrimination is the foundation for group identity for these two minority groups.

In summary, while there are some similarities between Latinos and African Americans in regard to measures of group identity, we conclude that the concepts used by scholars in the field to assess group identity need to be conceptualized and measured with knowledge that these concepts operate differently when applied to non-Blacks. For example, we strongly suggest that linked fate and group consciousness should not be used interchangeably when applied to non-Blacks.

Although this article reveals some very important implications for scholars working with the concept of group consciousness and linked fate, there remains plenty of room for additional work in this area. We would like to address one of the more surprising results from our analysis in our concluding remarks, that Latinos have the lowest reported levels of linked fate across all groups in the study. Given our theory regarding similar experiences with discrimination for Latinos and African Americans, as well as the similarities between Latinos and African Americans across the dimensions of group consciousness with this data, this result requires further discussion. On one hand, this result could be driven by variation in the diverse Latino population driven by national origin, language use, nativity and citizenship status, phenotype and a host of other factors scholars have suggested may pose limitations for the formation of linked fate for Latinos.

However, we believe that this finding highlights some of the limitations associated with the data utilized for our study. For example, we find that citizenship status is a critical source of variation for Latinos that has implications for the measurement of group identity. The dimensions of group consciousness vary by citizenship among Latinos, yet we cannot adequately assess this among the Asian American sample in this data given the limitations with the language of interview for this population. With Asian interviews only conducted in English we also lose the opportunity to fully explore potential variation in linked fate among Asian Americans based on language, citizenship status, as well as nativity due to the limited sample. Thus, the higher levels of linked fate found in this study for Asians relative to Latinos may be at least somewhat the product of these limitations in the data available. We feel that these are interesting and important hypotheses that should be developed further by scholars focused on understanding internal variation in group identity within populations with large foreign-born populations when better data becomes available.

Finally, although we want to stress that this dataset is the most appropriate for our analysis, it was collected in 2004 and much has happened politically that may have implications for racial identity. Most notably, the anti-immigrant political climate and unprecedented passage of punitive immigration laws across the US states may also have significant consequences for the formation of Latino linked fate. In fact, recent survey data collected by Latino Decisions has suggested that an overwhelming majority of Latino adults believe that there is both an anti-Latino and anti-immigrant climate in the United States today.8 It is very likely that this socio-political climate has increased perceptions of linked or common fate among the Latino population.

Beyond implications for lower reported levels of linked fate than anticipated, the time period of data collection has implications for more current drivers of group identity for other racial and ethnic groups as well. We have seen the election of the first African American to the presidency, with President Obama effectively mobilizing minority voters in ways that likely influence group identity. Similarly, there has been a significant increase in the multiracial population in the US over the past ten years, accompanied by advancement in our measurement approaches for this sub-group (Masuoka, 2010). Given that our study is not able to explore nuances within group identity within the multi-racial population, scholars should look to incorporate our approach with this population in the future. Finally, while exploring how inter-sectionality may influence group identity across racial/ethnic groups is outside of the scope of our analysis, exploring how gender consciousness intersects with racial and ethnic identity is definitely worth pursuing if data becomes available to do so. We hope that our analysis has improved our working knowledge of the concepts of group consciousness and linked fate so that scholars pursuing the research questions we could not address here will improve their research designs.

Footnotes

While Miller et al. (1981) did find evidence for group consciousness among one advantaged group tested, businessmen, they did not find it for Whites. Thus as concerns racial/ethnic groups we concur with Miller et al. (1981) and other scholars writing since that a perception of one’s racial/ethnic group as of lower status relative to other groups is one component of racial/ethnic group consciousness.

Although this is the best available dataset to test our research questions, there are several important limitations that are worth noting. As discussed in the paper, the Asian American respondents were not given the opportunity to conduct the interview in their language of choice. Furthermore, while the sample does include several racial/ethnic populations, Native Americans are not included in the sample, which limits our ability to explore whether this population is similar to African Americans.

We want to clarify that the creation of a latent factor underlying group consciousness does not imply moving away from a multi-dimensional conceptualization of this concept. Rather, we are attempting to determine if the measures typically associated with this concept are actually tapping into the same latent factor (group consciousness), providing scholars with justification to approach the measurement of this concept from a multidimensional perspective.

To test the robustness, we include both the Caribbean Black sample into the overall Black category and analyze them independently, and we find similar results.

Variable were all standardized to zero mean and unit variance before performing the singular value decomposition.

The analysis for Asians should be taken with some caution, as we are concerned about the limitations regarding language for the Asian sample. NPS was only administered in English and Spanish and does not adequately take into consideration the great variation in language for Asian populations.

To test the robustness, we include the Caribbean Black sample into the overall Black category as well as analyze them independently, and also find a one factor solution.

References

- Barreto Matt, Masuoka Natalie, Sanchez Gabriel. Religiosity, Discrimination and Group Identity Among Muslim Americans. Presented at the Western Political Science Association Annual Conference; San Diego. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán Cristina. The Trouble with Unity: Latino Politics and the Creation of Identity. Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chong Dennis, Rogers Reuel. Racial Solidarity and Political Participation. Political Behavior. 2005;27:347–374. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson Michael C. Behind the Mule: Race, Class and African American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- de la Garza Rodolfo, Vaughan David. The Political Socialization of Chicano Elites: A Generational Approach. Social Science Quarterly. 1984;65:290–307. [Google Scholar]

- Fraga Luis R, Garcia John A, Hero Rodney, Jones-Correa Michael, Martinez-Ebers Valerie, Segura Gary M. Latino National Survey (LNS), 2006. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2013. Jun 05, ICPSR20862-v6. http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR20862.v6. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia John. The Latino and African American Communities: Bases for Coalition Formation and Political Action. In: Jaynes Gerald., editor. Immigration and Race: New Challenges for American Democracy. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 2000. pp. 255–276. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia John. The 2000 National Census and its Implications for American Cities. In: Stokes Curtis, Melendez Theresa., editors. Racial Liberalism and the Politics of Urban America. Michigan State University Press; 2003. pp. 203–222. [Google Scholar]

- Greer Christina M. Black Ethnics: Race, Immigration, and the Pursuit of the American Dream. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gurin Patricia, Miller Arthur, Gurin Gerald. Stratum Identification and Consciousness. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1980;43:30–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild Jennifer. The Word American Ends in ‘I Can’: The Ambiguous Promise of the American Dream. William and Mary Law Review. 1992;34:139–170. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild Jan. Facing Up to the American Dream: Race, Class, and the Soul of the Nation. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson James S, Hutchings Vincent L, Brown Ronald, Wong Cara. National Politics Study, 2004. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2009. Mar 23, ICPSR24483-v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby William. Data Theory and Dimensional Analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Junn Jane, Mosuoka Natalie. Identities in Context: Racial Group Consciousness and Political Participation Among Asian American and Latino Young Adults” (with Jane Junn) Applied Developmental Science. 2008;12(2):93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kamasaki Charles. The Fair Housing Index: An Audit of Race and National Origin Discrimination in the Greater Washington Mortgage Lending Marketplace. Washington, DC: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann Karen. Cracks in the Rainbow: Group Commonality as a Basis for Latino and African-American Political Coalitions. Political Research Quarterly. 2003;56(2):199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Lavariega Monforti Jessica, Sanchez Gabriel. The Politics of Perception: An Investigation of the Presence and Sources for Perceptions of Internal Discrimination among Latinos. Social Science Quarterly. 2010;91(1):245–265. [Google Scholar]

- Leighley Jan. Strength in Numbers? The Political Mobilization of Racial and Ethnic Minorities. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lien Pei-te. Ethnicity and Political Participation: A Comparison Between Asians and Mexican Americans. Political Behavior. 1994;19:237–264. [Google Scholar]

- Lien Pei-te, Conway Margaret M, Wong Janelle. The Politics of Asian Americans. Vol. 2008 New York: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas, Denton NA. Racial Identity among Caribbean Hispanics: The Effect of Double Minority Status on Residential Segregation. American Sociological Review. 1989;54:790–808. [Google Scholar]

- Masuoka Natalie. Together They Become One: Examining the Predictors of Panethnic Group Consciousness Among Asian Americans and Latinos. Social Science Quarterly. 2006;87(5):993–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Masuoka Natalie. Defining the Group: Latino Identity and Political Participation. American Politics Research. 2008;36(1):33–61. [Google Scholar]

- Masuoka Natalie. The ‘Multiracial’ Option: Social Group Identity and Changing Patterns of Racial Categorization. American Politics Research. 2010;39(1):176–204. [Google Scholar]

- Masuoka Natalie, Sanchez Gabriel. Brown-Utility Heuristic? The Presence and Contributing Fators of Latino Linked Fate. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2010;32(4):519–531. [Google Scholar]

- McClain Paula D, Johson Carew Jessica D, Walton Eugene, Jr, Watts Candis S. Group Membership, Group Identity, and Group Consciousness: Measures of Racial Identity in American Politics? Annual Review of Political Science. 2009;12:471–485. [Google Scholar]

- Lavariega Monforti Jessica, Sanchez Gabriel. The Politics of Perception: An Investigation of the Presence and Sources of Perceptions of Internal Discrimination Among Latinos. Social Science Quarterly. 2010;91(1):245–265. [Google Scholar]

- Morin Jason. The Voting Behavior of Minority Judges in the U.S. Courts of Appeals: Does the Race of the Claimant Matter? American Politics Research. 2013;41(4):1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Arthur, Gurin Patrica, Gurin Gerald, Malanchuk Oksana. Group Consciousness and Political Participation. American Journal of Political Science. 1981;25:494–511. [Google Scholar]

- Olson Mancur. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen Marvin. Social and Political Participation of Blacks. American Sociological Review. 1970;35:682–697. [Google Scholar]

- Price Melanye T. Dreaming Blackness: Black Nationalism and African American Public Opinion. NYU Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shingles Richard. Black Consciousness and Political Participation: The Missing Link. American Political Science Review. 1981;75:76–9. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes-Brown Atiya. Latino Group Consciousness and Political Participation. American Politics Research. 2003;31(4):361–378. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Gabriel. The Role of Group Consciousness in Latino Public Opinion. Political Research Quarterly. 2006;59(3):435–446. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Gabriel. The Role of Group Consciousness In Political Participation Among Latinos in The United States. American Politics Research. 2006;34(4):427–451. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Gabriel. Latino Group Consciousness and Perceptions of Commonality With African Americans. Social Science Quarterly. 2008;89(2):428–444. [Google Scholar]

- Simien Evelyn M. Black Feminist Voices in Politics. SUNY Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Candice. The Politics of Black Pan-Ethnic Identity. New York: New York Univerity Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tate Katherine. From Protest to Politics, The New Black Voters in American Elections. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press and the Russell Sage Foundation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlaner Carole, Cain Bruce, Roderick Kiewiet D. Political Participation and Ethnic Minorities in the 1980s. Political Behavior. 1989;11:195–231. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlaner Carole. Perceived Discrimination and Prejudice and the Coalition Prospects of Blacks, Latinos, and Asian Americans. In: Jackson Bryan O, Preston Michael B., editors. Racial and Ethnic Politics in California. Berkeley, CA: IGS Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Verba Sidney, Nie Norman. Participation in America. New York: Harper; 1972. [Google Scholar]