Abstract

Although it is now evident that microRNAs (miRNAs) play a critical regulatory role in many, if not all, pathological and physiological processes, remarkably they have only formally been recognized for less than fifteen years. These endogenously produced short non-coding RNAs have created a new paradigm of gene control and have utility as both novel biomarkers of cancer and as potential therapeutics. In this review we consider the role of miRNAs in lymphoid biology both under physiological (i.e. lymphopoiesis) and malignant (i.e. lymphomagenesis) conditions. In addition to the functional significance of aberrant miRNA expression in lymphomas we discuss their use as novel biomarkers, both as a in situ tumour biomarker and as a non-invasive surrogate for the tumour by testing miRNAs in the blood of patients. Finally we consider the use of these molecules as potential therapeutic agents for lymphoma (and other cancer) patients and discuss some of the hurdles yet to be overcome in order to translate this potential into clinical practice

Keywords: Biomarker, Hematological malignancies, Lymphoid, Lymphoma, microRNA, ncRNA.

1. INTRODUCTION

According to the central dogma of molecular biology, biological information flows in one direction from DNA to RNA to protein [1]. The logical consequence of this dogma is that non-coding RNA (ncRNA) has no intrinsic value, however over 90% of transcriptional output in eukaryotes are non-coding [2]. Therefore it is perhaps unsurprising that microRNAs (miRNAs) were unknown to science up until just over 20 years ago, and not formally recognized until 2001 [3]. Now we realize that miRNAs play key regulatory roles in nearly every aspect of biology including cell differentiation, developmental timing, cell proliferation, apoptosis, organ development, metabolism, and hematopoiesis [4]. Approximately, 2/3 of all human genes are regulated directly by miRNAs [5], and now over 2500 human miRNAs have been identified [6]. The importance of miRNAs in cancer is suggested as most of them are located at cancer-associated genomic regions [7]. Furthermore, miRNAs are aberrantly expressed in all cancers including lymphoma [8]. There are many causes of dysfunctional expression in cancer including epigenetic deregulation, chromosomal aberrations, aberrant expression of transcription factors that regulate promoters of miRNAs, and factors that change miRNA biosynthesis or function [9].

Lymphoma is a cancer of the lymphatic system (B and T cells) representing the fifth most common cancer type worldwide and affecting more than a million people. The incidence of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) has increased74% in the US, between 1976 and 2001, and since then is the fifth most common form of death from cancer [10]. In this review we consider the role of miRNAs in lymphomas, their use as biomarkers and their potential as therapeutics.

2. ROLE OF MIRNAS IN LYMPHOPOIESIS

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) must balance their pluripotency whilst at the same time responding to lineage determining signals. This process is tightly regulated by a network of intrinsic and extrinsic stimuli, transcription factors, signaling pathways, cytokines, growth factors, and other molecular components. MiRNAs can target many of these as well as more generally determining HSC fate, differentiation state, self-renewal ability and function, apoptosis levels, and the balance of lymphoid and myeloid progenitor cells [11].

MiRNAs play a crucial role in hematopoiesis as demonstrated by the deletion of Dicer1, which severely inhibited peripheral CD8+ development as well as reducing numbers of CD4+ cells which when stimulated displayed increased apoptosis rates and low proliferatation [12]. However, when Dicer1 was deleted in CD34+ HSCs an increase in apoptosis occurred along with reduced hematopoietic ability [13], and when deleted in early B cell progenitors the pro to pre B cell transition was blocked as a result of miR-17~92 targeting of BIM which could be rescued by BCL2 expression [14].

The first study to look at miRNA involvement in lymphocyte development was in 2004, and demonstrated that miR-223, miR-181 and miR-142 were highly expressed in B-cells, and that HSCs expressing ectopic miR-181 significantly increased the numbers of B-cells and cytotoxic CD8+ T-cells in recipient mice [15]. miR-181 can also regulate levels of CD69, BCL2 and TCRα during T cell development [16], and is responsible for T-cell receptor sensitivity [17]. miR-155 deletion in mice made them immunodeficient, with B cells producing lower immunoglobulin levels after antigen treatment, and T cells producing reduced levels of IFNG and IL2. Both of these effects were mediated by regulation of PU.1 [18]. Activation of B cells or CD4+ T cells in vitro can up-regulate miR-155, whilst deletion of this miRNA in activated B cells reduces TNF and lymphotoxin levels as well biasing T cell differentiation towards the Th2 phenotype [19].

Both miR-155 and miR-181 are key regulators of germinal centre (GC) B-cell differentiation [20]. Deletion of Dicer1 in activated B cells reduces GC B-cell formation and consequent B-cells express higher levels of BIM [21]. GC B-cells are characterized by CD10, HGAL, BCL6, and LMO2 expression of the lack of the activated B-cell markers XBP1 or PRDM1/BLIMP1 [22]. miR-155 directly regulates levels of both HGAL and Rhotekin 2 [23], whilst the miR-30 family, miR-9 and let-7a, all target BCL6 and PRDM1/BLIMP1 [24]. miR-223 controls expression of LMO2 [25], and miR-125b of PRDM1/BLIMP1 and IRF4 [26]. miR-155 also regulates PU1 and CD10 modulating activated B-cell formation through NF-kB [27], and miR-125a/b can regulate TNFAIP3 promoting activation of NF-kB [28]. The miR-17-92 cluster is another essential regulator of lymphopoiesis. Targeted deletion of these miRNAs causes blockage of pro- to pre-B cell pathway as a result of BIM inhibition [29]. Members of the miR-17-92 cluster can also target other key immunomodulatory components including PP2A, PTEN and PRKAA1 [29, 30]. Pro- to pre-B cell development is also regulated by miR-34a and miR-150 via modulation of FOXP1 [31], and MYB respectively [32].

3. B-CELL LYMPHOMAS

As under physiological conditions there is a clear involvement of miRNAs in malignant lymphomagenesis in general. For example, Dicer1 deletion in a murine myc-lymphoma model decreased the incidence of lymphoma coupled with a change to very early B-cell precursor stage of diesase [33]. Similarly in a p53-null model, Dicer1 deletion reduced lymphomagenesis and conferred prolonged survival to the mice [34]. Below we discuss the involvement of miRNAs in the most common types of lymphoma.

3.1. Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) represents the most common lymphoid malignancy with an incidence of about 3 per 100,000 people and accounts for nearly 40% all lymphoid tumors [35]. DLBCL was one of the first lymphomas to be linked with aberrant miRNA expression, in particular the observation that miR-155 is highly expressed in this malignancy [36]. Indeed, forced over-expression of this miRNA in mice results in the development of a high grade B-cell lymphoma similar to DLBCL [37]. Further experimentation has shown that this oncogenicity is mediated by miR-155 targeting of SHIP1 and C/EBPβ [38]. When miR-155 was expressed in an inducible manner, although mice developed lymphoma, when the stimulus was removed the tumor quickly disappeared and after one week mice had no measurable disease at all [39]. In vitro, miR-155 expression suppresses the growth-inhibition of BMP2/4 and TGF-β1 in DLBCL cells via SMAD5 inhibition [40]. It can also regulate the PI3K-AKT pathway via targeting of PIK3R1 [41]. Interestingly it has been demonstrated that SHIP1 is differentially expressed in the two major molecular subtypes of DLBCL (i.e. activated B cell-like (ABC) and germinal center B cell-like (GC)) [42]. This is consistent with identified differences in miR-155 expression between GC- and ABC-type DLBCL [36b, 36c]. Moreover, CD10, associated with GC-type DLBCL [43], and constitutive NF-κB expression, the hallmark of ABC-type DLBCL [44], are linked through the miR-155/PU.1 pathway [27]. When mice were inoculated with U2932, an ABC-type DLBCL cell line treatment with exogenous miR-34a reduced tumor growth via targeting Foxp1 [45], a molecule associated with ABC-type DLBCL [22]. miR-34a is a well described tumor suppressor miRNA that is closely connected with the p53 network in solid tumors [46], and a positive feedback loop exists whereby p53 induces miR-34a expression and in turn miR-34a activates p53 through SIRT1 inhibition [47].

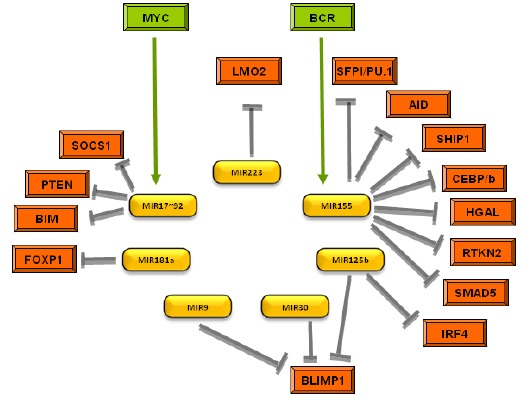

Over-expression of the miR-17~92 cluster in a Eµ-myc model resulted in increased aggressiveness of lymphoma development [48]. The MYC/miR-17-92/E2F circuit was shown to be responsible for this affect [49], as MYC up-regulates the miR-17-92 cluster which in turn targets E2F1, whilst conversely pro-proliferative E2F3 regulates the miR-17-92 cluster [50]. miR-19 has been identified as the key oncogenic component of the miR-17-92 cluster and can activate the Akt-mTOR pathway in the Eµ-myc model through PTEN antagonization resulting in the promotion of cell survival [51] (Fig. 1).

Fig. (1).

MiRNA implicated in the pathogenesis of DLBCL and their target genes.

3.2. Follicular Lymphoma (FL)

Despite follicular lymphoma (FL) being the most common indolent lymphoma, there are relatively few studies that have investigated miRNA expression in this disease. In the first of these, the levels of 153 miRNAs were measured in 46 FL samples and compared with DLBCL cases or normal lymph nodes [52]. Shortly afterwards, our group measured the expression levels of 464 miRNAs in 18 cases of FL and 80 cases of DLBCL [53]. In this publication we reported that the levels of six miRNAs (miR-223, miR-217, miR-222, miR-221, let-7i and let-7b) were differentially expressed between cases of FL that underwent high grade histological transformation compared to those that did not. More recently, the miR-17~92 cluster has been identified as a useful diagnostic differentiator between the potentially confounding diagnosis of GC-DLBCL and FL (grade 3) [54]. Another study compared FL with nodal marginal zone lymphoma (NMZL) [55], and yet another with follicular hyperplasia [56]. This latter study identified miRNAs associated with FL patients that responded to PACE chemotherapy, as well as showing that p21 and SOCS2 were regulated by miR-20a/b and miR-194 in FL cell lines.

Although >90% of FL cases have the t(14;18) translocation, a minority do not. Interestingly, a recent study identified 17 miRNAs that were differentially expressed between these diseases [57].

3.3. Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL)

Although relatively rare, mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is a particular aggressive lymphoma and the prognostic outcome of patients is poor. Several studies have looked at miRNA expression in MCL [58]. The loss of potential miRNA target sites for miR-15/16 and members of the miR-17-92 cluster in the 3'UTR of CCND1 are proposed to contribute to the characteristic Cyclin D1 over-expression in MCL [59]. Indeed, over-expression of miR-17~92 cluster members are correlated with high MYC expression in aggressive MCL [58c]. Similarly a high proliferation gene signature [58d], and activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway, as well as inhibition of chemotherapy-induced apoptosis are found in MCL cell lines [60]. PHLPP2, a key regulator of the PI3K/Akt pathway, has been shown to be targeted by the miR-17-92 cluster along with PTEN and BIM in MCL [61]. Inhibition of miR-17-92 expression in a xenotransplant model of MCL inhibited PI3K/Akt pathway and caused decreased tumor growth. Also the inhibition of miR-29 was demonstrated to activate CDK4/CDK6 in MCL, as well as acting as a potential prognostic marker for this disease [58a].

3.4. Burkitt Lymphoma (BL)

The hallmark of Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is the MYC-IgH (t(8;14)) translocation that results in over-expression of the MYC oncogene. Mice with a mutation in a miR-155 binding site of the 3´-UTR of the AID gene display increased levels of these translocations [62]. MYC regulates, and in turn itself is regulated by a large number of miRNAs. This results in a complex regulatory loop that is intimately involved in lymphomagenesis [63]. Indeed it has been suggested that MYC over-expression in BL cases without the t(8;14) translocation can be explained by miRNA deregulation [64]. In addition to a functional role, miRNAs could also facilitate classification of the group of B-cell lymphomas with intermediate features between DLBCL and BL [64].

3.5. Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL)

Ribonucleoprotein chromatin immunoprecipitation (RIP-ChIP) was used to look at the involvement of miRNAs Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) HL cell lines [65]. They found an over-representation of genes associated with cell proliferation, apoptosis and the p53 pathway. Elsewhere JAK2 was demonstrated to be regulated by miR-135a, and that over-expression increased apoptosis and decreases cell growth via Bcl-xL inhibition in HL cell lines [66]. Furthermore they observed that patients with low miR-135a had significantly poorer prognostic outcome. Inhibition of let-7 and miR-9 reduced the levels of PRDM1/BLIMP1 in HL cell lines preventing plasma cell differentiation [67]. In another study miR-9 was shown to target Dicer and HuR in HL. Inhibition of miR-9 led to a decrease in cytokine production and a reduced ability to attract inflammatory cells [68]. Ectopic administration of a miR-9 antagomir caused to decreased tumor growth in a xenotransplant model.

3.6. Other B-cell Lymphomas

A number of studies have looked at the role of miRNAs in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. For example, a 27-miRNA signature was identified that could distinguish between gastric DLBCL and MALT lymphoma [69]. This study proposed that the transformation from gastritis to MALT lymphoma is regulated epigenetically by methylation of miR-203, leading to the proposition that ABL1 might be a useful druggable target for this malignancy [70]. In another study five miRNAs (miR-150, miR-550, miR-124a, miR-518b and miR-539) were identified as being differentially expressed in MALT lymphoma compared to gastritis [71]. High E2A levels were found to correlate with increased miR-223 expression in gastric MALT lymphoma [72]. Finally, a miRNA signature of splenic marginal zone lymphoma (SMZL) cases was reported [73].

4. T-CELL LYMPHOMAS

Compared to their B-cell counterparts, very little is known about miRNA expression in T-cell lymphoma. Our group provided the first functional evidence for miRNAs in T-cell lymphomas in a study on Sézary syndrome (SzS), a rare aggressive primary cutaneous T-cell (CD4(+)) lymphoma [74]. We demonstrated that miR-342 plays an important pathogenic role in SzS by targeting RANKL which was associated with the protection of SzS cells from apoptosis. The identity of several of the miRNA we identified as being aberrantly expressed have subsequently been validated by other groups since [75]. More recently, further mechanistic insights into the role of miRNA in SzS showed that the widespread deficiency of PTEN observed in SzS might be in part explained by the dysregulation of miR-21, miR-106b, and miR-486 [76].

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is a common, indolent primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), with rare, more aggressive variants. A minority of the MF cases may undergo transformation associated with poor prognosis. Our group have also performed profiling studies on tumor stage MF [77], as well as in cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (cALCL) [78]. As a result of these, a qRT-PCR based classifier (miR-155, miR-203 and miR-205) has been proposed, able to distinguish between the various forms of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas and related benign disorders [79]. Importantly, both a training (n = 90) and a blinded test (n = 58) cohorts were used in this study. Besides its role in B-cell development, miR-150 also regulates NK cells via Myb targeting [80], as well as other T-cell subsets through NOTCH3 inhibition [81]. Transfection of miR-150 into NK/T cell lymphoma cell lines increased apoptosis and decreased cell proliferation. These effects were mediated via DKC1 and AKT2targeting, and caused a decrease in BIM, p53 and phospho-AKT levels. In addition, over-expression of miR-155 and miR-21 was shown to activate the PI3K-Akt pathway in NK/T-cell lymphomas [38c]. Also, over-expression of miR-122 in CTCL induced AKT phosphorylation linked to a decreased sensitivity to chemotherapy-induced apoptosis, as well as inhibiting p53 expression [82].

5. MIRNAS AS BIOMARKERS OF LYMPHOID MALIGNANCIES

The first demonstration that miRNAs could be useful as diagnostic biomarkers came from the 2002 groundbreaking publication of Calin and co-workers, who made the connection between the frequently deleted 13q14 locus, and the down-regulation of the miR-15a/16 cluster that is encoded within this region in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) patients [83]. Two years later, miRNAs were first demonstrated as prognostic biomarkers in lung cancer patients [84]. Since then, the speed of miRNA cancer biomarker discovery has been quite astonishing with over 9600 publications to date (source: Pubmed search (15/03/15) string= “(microRNA AND cancer) AND (prognosis OR diagnosis OR biomarker)”). The potential of miRNAs as cancer (diagnostic) biomarkers is obvious as particular miRNA expression profiles can distinguish cancers according to diagnosis and developmental stage of the tumor to a greater degree of accuracy than traditional gene expression analysis, even discriminating between cancers that are poorly separated histologically [85]. This ability is especially attractive to the field of B-cell lymphomas, a group of more than 35 recognized neoplasms [86] classified largely on the basis of immunohistochemical staining patterns, that are often challenging to accurately diagnose [87]. The usefulness of molecular methods to complement traditional morphological classifications in B-cell lymphoma is exemplified by DLBCL, where gene expression profiling has led to the identification of least two distinct subtypes that are prognostically and mechanistically very different, and respond differently to treatment [42, 88] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of deregulated ncRNAs in relationship with their potential as biomarkers in various lymphoma types.

| Lymphoma | miRNA | Biomarker Type | Sample Source | Cohort Size | P-value | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | ||||||

| DLBCL |

miR-155miR-210 miR-21 |

D | Serum | 60 | 43 | 0.009 0.02 0.04 |

[94] |

| miR-21 | D, P | Serum | 62 | 50 | < 0.001 | [106] | |

| miR-15a, miR-16-1, miR-29c, miR-34a, miR-155 | D | Serum | 75 | 77 | < 0.05 | [96] | |

| miR-155 | PR | Biopsy | 79 | - | 0.0008 | [102] | |

|

miR-18a miR-181a miR-222 |

P | Biopsy | 176 | - | 0.038 0.026 0.004 |

[101] | |

| SNORA48, miR-106b*, miR-106b, miR-1181, miR-124, miR-1299, miR-25*, miR-33b*, miR-432, miR-551b*, miR-629, miR-652, miR-654-3p, miR-671-5p, miR-766, miR-877*, miR-93, miR-93* | PR | Biopsy | 116 | - | 0.03 | [107] | |

| FL | miR-9, miR-9*, miR-301, miR-338, miR-213 | D | Biopsy | 46 | 7 | NA | [52] |

| miR-223, miR-217, miR-222, miR-221, let-7i, let-7b | P | Biopsy | 7 | 11 | < 0.05 | [53] | |

| MCL | miR-29 | P | Biopsy | 30 | - | 0.04 | [58a] |

| HL | miR-494, miR-1973, miR-21 | D | Plasma | 42 | 20 | 0.004 0.007 < 0.0001 |

[99] |

| miR-135a | P | Biopsy | 89 | - | 0.04 | [66] | |

| miR-21, miR-30e, miR-30d, miR-92b | P, PR | Biopsy | 29 | - | < 0.001 | [108] | |

| MALT | miR-150, miR-550, miR-124a, miR-518b, miR-539 | D | Biopsy | NA | NA | < 0.001 | [71] |

| SzS | miR-150, miR-191, miR-15a, miR-16 | D | PBMCs | 36 | 12 | 0.04 | [109] |

|

miR-21 miR-214 miR-486 |

P | PBMCs | 23 | - | 0.03 0.004 0.0038 |

[75b] | |

| MF |

miR-155 miR-92a miR-93 |

D | Biopsy | 19 | 12 | 0.014 0.001 0.001 |

[77] |

| NK/T-cell | miR-221 | D, P | Plasma | 79 | 37 | 0.038 | [100] |

ncRNA, non-coding RNA; miR, microRNA; SNOR, small nucleolar RNAs; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FL, follicular lymphoma; MCL, mantle-cell lymphoma; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; MALT, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma; SzS, Sézary syndrome; MF, mycosis fungoides; NK/T-cell, extra-nodal natural killer T-Cell (NK/T-cell) lymphoma; D, Diagnostic Biomarker; P, prognostic Biomarker; PR, Predictive of response to treatment Biomarker; MV, microvesicles; PBMCs, peripheral blood monuclear cells; NA, not available.

5.1. miRNAs As Non-invasive Biomarkers of B-cell Lymphoma

An additional feature of miRNAs that make them attractive candidates as cancer biomarkers is that they are much more stable than other RNA species and, as a result, can be purified and measured easily in routinely prepared formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) biopsy material [36b] and biological fluids such as blood or its derivatives (sera, plasma) [89]. The standard protocol for many cancers (including lymphoma) diagnosis remains the histopathological inspection of tumor material obtained by invasive biopsy; a procedure that is rather frequently expensive, uncomfortable and sometimes risky for patients. Therefore there has been great interest in the field of circulating nucleic acids in blood as non-invasive cancer biomarkers [90]. An additional benefit of blood-based testing is the capability to perform screening and repeat sampling on patients undergoing therapy, or monitoring disease progression allowing for the development of a personalised approach to cancer patient management. Unlike other RNA molecules, the vast majority of which are degraded by high levels of RNases found in the blood [91], miRNAs seem to be stable in the blood and are surprisingly resistant to fragmentation by either chemical or enzymatic agents [92].

In 2007 we first reported the presence of miRNAs in the blood of lymphoma patients [93] and in 2008 demonstrated the up-regulation of miR-155 and miR-210 in the blood (sera) of DLBCL patients compared to healthy controls, as well as the prognostic potential of miR-21 [94], an observation validated independently some years later [95]. In addition to confirming the up-regulation of miR-155 in DLBCL sera, another study also reported up-regulation of miR-15a, miR-16 and miR-29c, and down-regulation of miR-34a [96]. A third study, this time in plasma rather than sera, observed reduced levels of miR-92 that varied in response to chemotherapy in DLBCL, FL and T-cell non-Hodgkins lymphoma patients [97]. Similarly, plasma levels of miR-92a have been proposed as diagnostic/prognostic biomarkers for multiple myeloma (MM) [97, 98].

In HL patient, plasma levels of miR-494 and miR-1973 were identified as indicators of both relapse and interim therapy response [99]. In addition, plasma miR-221 has been found to be a good diagnostic and prognostic marker for extranodal natural killer T-Cell NK/Tcell lymphoma [100].

Clearly although results are very preliminary, the ability of miRNAs to act as non-invasive biomarkers of B-cell lymphomas is a promising prospect (Table 1).

6. MIRNAS AS PREDICTIVE MARKERS OF RESPONSE AND POTENTIAL THERAPEUTIC USES

Recently, miRNA profiling of different B-cell lymphomas has been shown to be useful beyond the mere classification of different lymphoma entities. For example, a 6-gene model combined with the international prognostic index (IPI) and with a three-miRNA expression signature could predict patients’ outcome in a series of 176 uniformly treated DLBCL cases, and correlated the results to survival [101]. More recently, Iqbal and collaborators have found a predictive miRNA signature in DLBCL, associated with R-CHOP response failure. This signature included high expression levels of miR-155, as we have previously reported [53]. Furthermore, in vitro overexpression of miR-155 sensitized cells to AKT inhibitors, suggesting a novel treatment option for resistant DLBCL [102].

Indeed, probably the most promising clinical aspect of miRNAs is their potential as novel therapeutic molecules, either as a tool to modulate target genes associated with disease, or by correcting dysfunctional expression of the miRNAs themselves. The former approach is particularly attractive because a single miRNA can be used against multiple components of a disease pathway or even against the pathway in its entirety [103]. There are two major strategies to therapeutically modulate deregulated miRNAs in cancer; the first to use miRNA mimics to restore physiological levels of miRNAs that are down-regulated for example tumor suppressor miRNAs such as miR-34 or let-7. A second strategy is to use inhibitors of over-expressed miRNAs for example directed against so-called oncomirs such as miR-21 or miR-155 [39, 104].

There now exists a wealth of in vivo animal evidence that have provided the proof-of-principle of the therapeutic efficacy of miRNAs in disease; however, at present all but a couple of these studies remain at the pre-clinical stage. Translating these results into the clinic need first addressing a few major issues, such as the effective targeting of therapy (e.g. tissue-specific delivery, dosage and pharmacodynamics), as well as safety concerns (e.g. off-target effects, RNA-mediated immunostimulation and the use of viral vectors etc.). Indeed, although a number of strategies to deliver miRNA in experimental models have been used in research, clinically applicable tools for gene delivery are limited and currently are focused on retroviral-based or adenoviral-based vectors.

In addition to viral vector-based gene therapy, synthetic miRNA has also been used in gain-of-function assays. These miRNA mimics are small, chemically modified RNA molecules that resemble endogenous mature miRNA molecules that are commercially available [105]. By the use of formulated synthetic miRNA, the therapeutic potential of exogenous miR-34a against human multiple myeloma cells in vitro and in vivo has been successful in preclinical models. This favorable outcome is a proof of concept that supports the use of formulated miR-34a based treatment strategies in patients [104a]. MiRNA mimics have no vector-based toxicity; therefore, if their delivery agents do not cause side effects over long-term use, they can be a promising therapeutic approach for tumors.

That said, this is an area very much still in its infancy that is almost certain to flourish in the near future as the field matures, and promises to add to the current battery of therapies available to clinicians in the continual fight against lymphoma.

7. CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Over the last years, a number of studies have underlined the key role that miRNAs have in lymphoma, both in B-cell and in T-cell malignancies. They interfere with multiple pathways involved in cell cycle, tumor growth and apoptosis, acting as tumor suppressor or oncogenes. Interestingly, different lymphoma subtypes have distinct miRNAs expression profiles. Their ability to improve histological classification and their stability in body fluids make them ideal biomarkers. Further studies and clinical trials are needed to confirm the prognostic and predictive power of miRNAs, as well as to test the miRNAs and their blocking molecules as a therapeutic approach for lymphoma.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We apologize to the authors of the many studies that were not included in this review due to space limitations. CHL and his research are supported by funding from the Starmer-Smith memorial lymphoma Fund, Ikerbasque (the Basque Foundation for Science), MINECO (Spanish Ministry in charge of R&D&i), Gobierno Vasco and Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa. MFM is supported by the Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer (AECC).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author(s) confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crick F. Central dogma of molecular biology. Nature. 1970;227(5258):561–563. doi: 10.1038/227561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattick J.S. Non-coding RNAs: the architects of eukaryotic complexity. EMBO Rep. 2001;2(11):986–991. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee R.C., Ambros V. An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;294(5543):862–864. doi: 10.1126/science.1065329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim V.N. MicroRNA biogenesis: coordinated cropping and dicing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6(5):376–385. doi: 10.1038/nrm1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman R.C., Farh K.K., Burge C.B., Bartel D.P. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19(1):92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffiths-Jones S., Grocock R.J., van Dongen S., Bateman A., Enright A.J. miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Database issue):D140–D144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calin G.A., Sevignani C., Dumitru C.D., Hyslop T., Noch E., Yendamuri S., Shimizu M., Rattan S., Bullrich F., Negrini M., Croce C.M. Human microRNA genes are frequently located at fragile sites and genomic regions involved in cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101(9):2999–3004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307323101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a)Lawrie C.H. MicroRNA expression in lymphoid malignancies: new hope for diagnosis and therapy? J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2008;12(5A):1432–1444. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Iorio M.V., Croce C.M. MicroRNAs in cancer: small molecules with a huge impact. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27(34):5848–5856. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Croce C.M. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10(10):704–714. doi: 10.1038/nrg2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cancer Statistics Review S.E. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2002. National Cancer Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Georgantas R.W., III, Hildreth R., Morisot S., Alder J., Liu C.G., Heimfeld S., Calin G.A., Croce C.M., Civin C.I. CD34+ hematopoietic stem-progenitor cell microRNA expression and function: a circuit diagram of differentiation control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104(8):2750–2755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610983104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a)Cobb B.S., Nesterova T.B., Thompson E., Hertweck A., O'Connor E., Godwin J., Wilson C.B., Brockdorff N., Fisher A.G., Smale S.T., Merkenschlager M. T cell lineage choice and differentiation in the absence of the RNase III enzyme Dicer. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201(9):1367–1373. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b)Muljo S.A., Ansel K.M., Kanellopoulou C., Livingston D.M., Rao A., Rajewsky K. Aberrant T cell differentiation in the absence of Dicer. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202(2):261–269. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo S., Lu J., Schlanger R., Zhang H., Wang J.Y., Fox M.C., Purton L.E., Fleming H.H., Cobb B., Merkenschlager M., Golub T.R., Scadden D.T. MicroRNA miR-125a controls hematopoietic stem cell number. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107(32):14229–14234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913574107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koralov S.B., Muljo S.A., Galler G.R., Krek A., Chakraborty T., Kanellopoulou C., Jensen K., Cobb B.S., Merkenschlager M., Rajewsky N., Rajewsky K. Dicer ablation affects antibody diversity and cell survival in the B lymphocyte lineage. Cell. 2008;132(5):860–874. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen C.Z., Li L., Lodish H.F., Bartel D.P. MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science. 2004;303(5654):83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1091903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neilson J.R., Zheng G.X., Burge C.B., Sharp P.A. Dynamic regulation of miRNA expression in ordered stages of cellular development. Genes Dev. 2007;21(5):578–589. doi: 10.1101/gad.1522907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Q.J., Chau J., Ebert P.J., Sylvester G., Min H., Liu G., Braich R., Manoharan M., Soutschek J., Skare P., Klein L.O., Davis M.M., Chen C.Z. miR-181a is an intrinsic modulator of T cell sensitivity and selection. Cell. 2007;129(1):147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a)Rodriguez A., Vigorito E., Clare S., Warren M.V., Couttet P., Soond D.R., van Dongen S., Grocock R.J., Das P.P., Miska E.A., Vetrie D., Okkenhaug K., Enright A.J., Dougan G., Turner M., Bradley A. Requirement of bic/microRNA-155 for normal immune function. Science. 2007;316(5824):608–611. doi: 10.1126/science.1139253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b)Thai T.H., Calado D.P., Casola S., Ansel K.M., Xiao C., Xue Y., Murphy A., Frendewey D., Valenzuela D., Kutok J.L., Schmidt-Supprian M., Rajewsky N., Yancopoulos G., Rao A., Rajewsky K. Regulation of the germinal center response by microRNA-155. Science. 2007;316(5824):604–608. doi: 10.1126/science.1141229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vigorito E., Perks K.L., Abreu-Goodger C., Bunting S., Xiang Z., Kohlhaas S., Das P.P., Miska E.A., Rodriguez A., Bradley A., Smith K.G., Rada C., Enright A.J., Toellner K.M., Maclennan I.C., Turner M. microRNA-155 regulates the generation of immunoglobulin class-switched plasma cells. Immunity. 2007;27(6):847–859. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a)de Yebenes V.G., Belver L., Pisano D.G., Gonzalez S., Villasante A., Croce C., He L., Ramiro A.R. miR-181b negatively regulates activation-induced cytidine deaminase in B cells. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205(10):2199–2206. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b)Teng G., Hakimpour P., Landgraf P., Rice A., Tuschl T., Casellas R., Papavasiliou F.N. MicroRNA-155 is a negative regulator of activation-induced cytidine deaminase. Immunity. 2008;28(5):621–629. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu S., Guo K., Zeng Q., Huo J., Lam K.P. The RNase III enzyme Dicer is essential for germinal center B-cell formation. Blood. 2012;119(3):767–776. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-355412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi W.W., Weisenburger D.D., Greiner T.C., Piris M.A., Banham A.H., Delabie J., Braziel R.M., Geng H., Iqbal J., Lenz G., Vose J.M., Hans C.P., Fu K., Smith L.M., Li M., Liu Z., Gascoyne R.D., Rosenwald A., Ott G., Rimsza L.M., Campo E., Jaffe E.S., Jaye D.L., Staudt L.M., Chan W.C. A new immunostain algorithm classifies diffuse large B-cell lymphoma into molecular subtypes with high accuracy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15(17):5494–5502. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dagan L.N., Jiang X., Bhatt S., Cubedo E., Rajewsky K., Lossos I.S. miR-155 regulates HGAL expression and increases lymphoma cell motility. Blood. 2012;119(2):513–520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-370536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin J., Lwin T., Zhao J.J., Tam W., Choi Y.S., Moscinski L.C., Dalton W.S., Sotomayor E.M., Wright K.L., Tao J. Follicular dendritic cell-induced microRNA-mediated upregulation of PRDM1 and downregulation of BCL-6 in non-Hodgkin ?(tm)s B-cell lymphomas. Leukemia. 2011;25(1):145–152. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gururajan M., Haga C.L., Das S., Leu C.M., Hodson D., Josson S., Turner M., Cooper M.D. MicroRNA 125b inhibition of B cell differentiation in germinal centers. Int. Immunol. 2010;22(7):583–592. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malumbres R., Sarosiek K.A., Cubedo E., Ruiz J.W., Jiang X., Gascoyne R.D., Tibshirani R., Lossos I.S. Differentiation stage-specific expression of microRNAs in B lymphocytes and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2009;113(16):3754–3764. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson R.C., Herscovitch M., Zhao I., Ford T.J., Gilmore T.D. NF-kappaB down-regulates expression of the B-lymphoma marker CD10 through a miR-155/PU.1 pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(3):1675–1682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.177063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim S.W., Ramasamy K., Bouamar H., Lin A.P., Jiang D., Aguiar R.C. MicroRNAs miR-125a and miR-125b constitutively activate the NF-I B pathway by targeting the tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3, A20). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109(20):7865–7870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200081109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ventura A., Young A.G., Winslow M.M., Lintault L., Meissner A., Erkeland S.J., Newman J., Bronson R.T., Crowley D., Stone J.R., Jaenisch R., Sharp P.A., Jacks T. Targeted deletion reveals essential and overlapping functions of the miR-17 through 92 family of miRNA clusters. Cell. 2008;132(5):875–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.(a)Xiao C., Srinivasan L., Calado D.P., Patterson H.C., Zhang B., Wang J., Henderson J.M., Kutok J.L., Rajewsky K. Lymphoproliferative disease and autoimmunity in mice with increased miR-17-92 expression in lymphocytes. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9(4):405–414. doi: 10.1038/ni1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b)Mu P., Han Y.C., Betel D., Yao E., Squatrito M., Ogrodowski P., de Stanchina E., D'Andrea A., Sander C., Ventura A. Genetic dissection of the miR-17~92 cluster of microRNAs in Myc-induced B-cell lymphomas. Genes Dev. 2009;23(24):2806–2811. doi: 10.1101/gad.1872909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c)Mavrakis K.J., Wolfe A.L., Oricchio E., Palomero T., de Keersmaecker K., McJunkin K., Zuber J., James T., Khan A.A., Leslie C.S., Parker J.S., Paddison P.J., Tam W., Ferrando A., Wendel H.G. Genome-wide RNA-mediated interference screen identifies miR-19 targets in Notch-induced T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12(4):372–379. doi: 10.1038/ncb2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rao D.S., O'Connell R.M., Chaudhuri A.A., Garcia-Flores Y., Geiger T.L., Baltimore D. MicroRNA-34a perturbs B lymphocyte development by repressing the forkhead box transcription factor Foxp1. Immunity. 2010;33(1):48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou B., Wang S., Mayr C., Bartel D.P., Lodish H.F. miR-150, a microRNA expressed in mature B and T cells, blocks early B cell development when expressed prematurely. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104(17):7080–7085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702409104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arrate M.P., Vincent T., Odvody J., Kar R., Jones S.N., Eischen C.M. MicroRNA biogenesis is required for Myc-induced B-cell lymphoma development and survival. Cancer Res. 2010;70(14):6083–6092. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adams C.M., Eischen C.M. Inactivation of p53 is insufficient to allow B cells and B-cell lymphomas to survive without Dicer. Cancer Res. 2014;74(14):3923–3934. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coiffier B. Diffuse large cell lymphoma. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2001;13(5):325–334. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200109000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.(a) Kluiver J., Poppema S., de Jong D., Blokzijl T., Harms G., Jacobs S., Kroesen B.J., van den Berg A. BIC and miR-155 are highly expressed in Hodgkin, primary mediastinal and diffuse large B cell lymphomas. J. Pathol. 2005;207(2):243–249. doi: 10.1002/path.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lawrie C.H., Soneji S., Marafioti T., Cooper C.D., Palazzo S., Paterson J.C., Cattan H., Enver T., Mager R., Boultwood J., Wainscoat J.S., Hatton C.S. MicroRNA expression distinguishes between germinal center B cell-like and activated B cell-like subtypes of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Int. J. Cancer. 2007;121(5):1156–1161. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Eis P.S., Tam W., Sun L., Chadburn A., Li Z., Gomez M.F., Lund E., Dahlberg J.E. Accumulation of miR-155 and BIC RNA in human B cell lymphomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102(10):3627–3632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500613102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costinean S., Zanesi N., Pekarsky Y., Tili E., Volinia S., Heerema N., Croce C.M. Pre-B cell proliferation and lymphoblastic leukemia/high-grade lymphoma in E(mu)-miR155 transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103(18):7024–7029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602266103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.(a) O'Connell R.M., Chaudhuri A.A., Rao D.S., Baltimore D. Inositol phosphatase SHIP1 is a primary target of miR-155. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106(17):7113–7118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902636106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pedersen I.M., Otero D., Kao E., Miletic A.V., Hother C., Ralfkiaer E., Rickert R.C., Gronbaek K., David M. Onco-miR-155 targets SHIP1 to promote TNFalpha-dependent growth of B cell lymphomas. EMBO Mol. Med. 2009;1(5):288–295. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yamanaka Y., Tagawa H., Takahashi N., Watanabe A., Guo Y.M., Iwamoto K., Yamashita J., Saitoh H., Kameoka Y., Shimizu N., Ichinohasama R., Sawada K. Aberrant overexpression of microRNAs activate AKT signaling via down-regulation of tumor suppressors in natural killer-cell lymphoma/leukemia. Blood. 2009;114(15):3265–3275. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-222794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Babar I.A., Cheng C.J., Booth C.J., Liang X., Weidhaas J.B., Saltzman W.M., Slack F.J. Nanoparticle-based therapy in an in vivo microRNA-155 (miR-155)-dependent mouse model of lymphoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109(26):E1695–E1704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201516109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rai D., Kim S.W., McKeller M.R., Dahia P.L., Aguiar R.C. Targeting of SMAD5 links microRNA-155 to the TGF-beta pathway and lymphomagenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107(7):3111–3116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910667107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang X., Shen Y., Liu M., Bi C., Jiang C., Iqbal J., McKeithan T.W., Chan W.C., Ding S.J., Fu K. Quantitative proteomics reveals that miR-155 regulates the PI3K-AKT pathway in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2012;181(1):26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alizadeh A.A., Eisen M.B., Davis R.E., Ma C., Lossos I.S., Rosenwald A., Boldrick J.C., Sabet H., Tran T., Yu X., Powell J.I., Yang L., Marti G.E., Moore T., Hudson J., Jr, Lu L., Lewis D.B., Tibshirani R., Sherlock G., Chan W.C., Greiner T.C., Weisenburger D.D., Armitage J.O., Warnke R., Levy R., Wilson W., Grever M.R., Byrd J.C., Botstein D., Brown P.O., Staudt L.M. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403(6769):503–511. doi: 10.1038/35000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hans C.P., Weisenburger D.D., Greiner T.C., Gascoyne R.D., Delabie J., Ott G., Muller-Hermelink H.K., Campo E., Braziel R.M., Jaffe E.S., Pan Z., Farinha P., Smith L.M., Falini B., Banham A.H., Rosenwald A., Staudt L.M., Connors J.M., Armitage J.O., Chan W.C. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood. 2004;103(1):275–282. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Compagno M., Lim W.K., Grunn A., Nandula S.V., Brahmachary M., Shen Q., Bertoni F., Ponzoni M., Scandurra M., Califano A., Bhagat G., Chadburn A., Dalla-Favera R., Pasqualucci L. Mutations of multiple genes cause deregulation of NF-kappaB in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 2009;459(7247):717–721. doi: 10.1038/nature07968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Craig V.J., Tzankov A., Flori M., Schmid C.A., Bader A.G., Muller A. Systemic microRNA-34a delivery induces apoptosis and abrogates growth of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in vivo. Leukemia. 2012;26(11):2421–2424. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He L., He X., Lim L.P., de Stanchina E., Xuan Z., Liang Y., Xue W., Zender L., Magnus J., Ridzon D., Jackson A.L., Linsley P.S., Chen C., Lowe S.W., Cleary M.A., Hannon G.J. A microRNA component of the p53 tumour suppressor network. Nature. 2007;447(7148):1130–1134. doi: 10.1038/nature05939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamakuchi M., Lowenstein C.J. MiR-34, SIRT1 and p53: the feedback loop. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(5):712–715. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.5.7753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.(a) He L., Thomson J.M., Hemann M.T., Hernando-Monge E., Mu D., Goodson S., Powers S., Cordon-Cardo C., Lowe S.W., Hannon G.J., Hammond S.M. A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature. 2005;435(7043):828–833. doi: 10.1038/nature03552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tagawa H., Karube K., Tsuzuki S., Ohshima K., Seto M. Synergistic action of the microRNA-17 polycistron and Myc in aggressive cancer development. Cancer Sci. 2007;98(9):1482–1490. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O'Donnell K.A., Wentzel E.A., Zeller K.I., Dang C.V., Mendell J.T. c-Myc-regulated microRNAs modulate E2F1 expression. Nature. 2005;435(7043):839–843. doi: 10.1038/nature03677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woods K., Thomson J.M., Hammond S.M. Direct regulation of an oncogenic micro-RNA cluster by E2F transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282(4):2130–2134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600252200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Olive V., Bennett M.J., Walker J.C., Ma C., Jiang I., Cordon-Cardo C., Li Q.J., Lowe S.W., Hannon G.J., He L. miR-19 is a key oncogenic component of mir-17-92. Genes Dev. 2009;23(24):2839–2849. doi: 10.1101/gad.1861409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roehle A., Hoefig K.P., Repsilber D., Thorns C., Ziepert M., Wesche K.O., Thiere M., Loeffler M., Klapper W., Pfreundschuh M., Matolcsy A., Bernd H.W., Reiniger L., Merz H., Feller A.C. MicroRNA signatures characterize diffuse large B-cell lymphomas and follicular lymphomas. Br. J. Haematol. 2008;142(5):732–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lawrie C.H., Chi J., Taylor S., Tramonti D., Ballabio E., Palazzo S., Saunders N.J., Pezzella F., Boultwood J., Wainscoat J.S., Hatton C.S. Expression of microRNAs in diffuse large B cell lymphoma is associated with immunophenotype, survival and transformation from follicular lymphoma. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009;13(7):1248–1260. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00628.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fassina A., Marino F., Siri M., Zambello R., Ventura L., Fassan M., Simonato F., Cappellesso R. The miR-17-92 microRNA cluster: a novel diagnostic tool in large B-cell malignancies. Lab. Invest. 2012;92(11):1574–1582. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arribas A.J., Campos-Martin Y., Gomez-Abad C., Algara P., Sanchez-Beato M., Rodriguez-Pinilla M.S., Montes-Moreno S., Martinez N., Alves-Ferreira J., Piris M.A., Mollejo M. Nodal marginal zone lymphoma: gene expression and miRNA profiling identify diagnostic markers and potential therapeutic targets. Blood. 2012;119(3):e9–e21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-339556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang W., Corrigan-Cummins M., Hudson J., Maric I., Simakova O., Neelapu S.S., Kwak L.W., Janik J.E., Gause B., Jaffe E.S., Calvo K.R. MicroRNA profiling of follicular lymphoma identifies microRNAs related to cell proliferation and tumor response. Haematologica. 2012;97(4):586–594. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.048132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leich E., Zamo A., Horn H., Haralambieva E., Puppe B., Gascoyne R.D., Chan W.C., Braziel R.M., Rimsza L.M., Weisenburger D.D., Delabie J., Jaffe E.S., Fitzgibbon J., Staudt L.M., Mueller-Hermelink H.K., Calaminici M., Campo E., Ott G., HernA ndez L., Rosenwald A. MicroRNA profiles of t(14;18)-negative follicular lymphoma support a late germinal center B-cell phenotype. Blood. 2011;118(20):5550–5558. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-361972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.(a) Zhao J.J., Lin J., Lwin T., Yang H., Guo J., Kong W., Dessureault S., Moscinski L.C., Rezania D., Dalton W.S., Sotomayor E., Tao J., Cheng J.Q. microRNA expression profile and identification of miR-29 as a prognostic marker and pathogenetic factor by targeting CDK6 in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2010;115(13):2630–2639. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-243147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Di Lisio L., Gomez-Lopez G., Sanchez-Beato M., Gomez-Abad C., Rodriguez M.E., Villuendas R., Ferreira B.I., Carro A., Rico D., Mollejo M., Martinez M.A., Menarguez J., Diaz-Alderete A., Gil J., Cigudosa J. C., Pisano D.G., Piris M.A., Martinez N. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed]; (c) Navarro A., BeA S., Fernandez V., Prieto M., Salaverria I., Jares P., Hartmann E., Mozos A., Lopez-Guillermo A., Villamor N., Colomer D., Puig X., Ott G., Sole F., Serrano S., Rosenwald A., Campo E., Hernandez L. MicroRNA expression, chromosomal alterations, and immunoglobulin variable heavy chain hypermutations in Mantle cell lymphomas. Cancer Res. 2009;69(17):7071–7078. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Iqbal J., Shen Y., Liu Y., Fu K., Jaffe E.S., Liu C., Liu Z., Lachel C.M., Deffenbacher K., Greiner T.C., Vose J.M., Bhagavathi S., Staudt L.M., Rimsza L., Rosenwald A., Ott G., Delabie J., Campo E., Braziel R.M., Cook J.R., Tubbs R.R., Gascoyne R.D., Armitage J.O., Weisenburger D.D., McKeithan T.W., Chan W.C. Genome-wide miRNA profiling of mantle cell lymphoma reveals a distinct subgroup with poor prognosis. Blood. 2012;119(21):4939–4948. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-370122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.(a) Chen R.W., Bemis L.T., Amato C.M., Myint H., Tran H., Birks D.K., Eckhardt S.G., Robinson W.A. Truncation in CCND1 mRNA alters miR-16-1 regulation in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2008;112(3):822–829. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-142182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Deshpande A., Pastore A., Deshpande A.J., Zimmermann Y., Hutter G., Weinkauf M., Buske C., Hiddemann W., Dreyling M. 3'UTR mediated regulation of the cyclin D1 proto-oncogene. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(21):3592–3600. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.21.9993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chaudhuri A.A., So A.Y., Mehta A., Minisandram A., Sinha N., Jonsson V.D., Rao D.S., O'Connell R.M., Baltimore D. Oncomir miR-125b regulates hematopoiesis by targeting the gene Lin28A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109(11):4233–4238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200677109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rao E., Jiang C., Ji M., Huang X., Iqbal J., Lenz G., Wright G., Staudt L.M., Zhao Y., McKeithan T.W., Chan W.C., Fu K. The miRNA-17 ^1/492 cluster mediates chemoresistance and enhances tumor growth in mantle cell lymphoma via PI3K/AKT pathway activation. Leukemia. 2012;26(5):1064–1072. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dorsett Y., McBride K.M., Jankovic M., Gazumyan A., Thai T.H., Robbiani D.F., Di Virgilio M., Reina San-Martin B., Heidkamp G., Schwickert T.A., Eisenreich T., Rajewsky K., Nussenzweig M.C. MicroRNA-155 suppresses activation-induced cytidine deaminase-mediated Myc-Igh translocation. Immunity. 2008;28(5):630–638. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.(a) Gao P., Tchernyshyov I., Chang T.C., Lee Y.S., Kita K., Ochi T., Zeller K.I., De Marzo A.M., Van Eyk J.E., Mendell J.T., Dang C.V. c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature. 2009;458(7239):762–765. doi: 10.1038/nature07823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chang T.C., Yu D., Lee Y.S., Wentzel E.A., Arking D.E., West K.M., Dang C.V., Thomas-Tikhonenko A., Mendell J.T. Widespread microRNA repression by Myc contributes to tumorigenesis. Nat. Genet. 2008;40(1):43–50. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c)Bueno M.J., Gomez de Cedron M., Gomez-Lopez G., Perez de Castro I., Di Lisio L., Montes-Moreno S., Martinez N., Guerrero M., Sanchez-Martinez R., Santos J., Pisano D.G., Piris M.A., Fernandez-Piqueras J., Malumbres M. Combinatorial effects of microRNAs to suppress the Myc oncogenic pathway. Blood. 2011;117(23):6255–6266. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-315432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leucci E., Cocco M., Onnis A., De Falco G., van Cleef P., Bellan C., van Rijk A., Nyagol J., Byakika B., Lazzi S., Tosi P., van Krieken H., Leoncini L. MYC translocation-negative classical Burkitt lymphoma cases: an alternative pathogenetic mechanism involving miRNA deregulation. J. Pathol. 2008;216(4):440–450. doi: 10.1002/path.2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tan L.P., Seinen E., Duns G., de Jong D., Sibon O.C., Poppema S., Kroesen B.J., Kok K., van den Berg A. A high throughput experimental approach to identify miRNA targets in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(20):e137. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Navarro A., Diaz T., Martinez A., Gaya A., Pons A., Gel B., Codony C., Ferrer G., Martinez C., Montserrat E., Monzo M. Regulation of JAK2 by miR-135a: prognostic impact in classic Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2009;114(14):2945–2951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-204842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nie K., Gomez M., Landgraf P., Garcia J.F., Liu Y., Tan L.H., Chadburn A., Tuschl T., Knowles D.M., Tam W. MicroRNA-mediated down-regulation of PRDM1/Blimp-1 in Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cells: a potential pathogenetic lesion in Hodgkin lymphomas. Am. J. Pathol. 2008;173(1):242–252. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leucci E., Zriwil A., Gregersen L.H., Jensen K.T., Obad S., Bellan C., Leoncini L., Kauppinen S., Lund A.H. Inhibition of miR-9 de-represses HuR and DICER1 and impairs Hodgkin lymphoma tumour outgrowth in vivo. Oncogene. 2012;31(49):5081–5089. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Craig V.J., Cogliatti S.B., Imig J., Renner C., Neuenschwander S., Rehrauer H., Schlapbach R., Dirnhofer S., Tzankov A., Muller A. Myc-mediated repression of microRNA-34a promotes high-grade transformation of B-cell lymphoma by dysregulation of FoxP1. Blood. 2011;117(23):6227–6236. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-312231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Craig V.J., Cogliatti S.B., Rehrauer H., Wundisch T., MA1/4ller A. Epigenetic silencing of microRNA-203 dysregulates ABL1 expression and drives Helicobacter-associated gastric lymphomagenesis. Cancer Res. 2011;71(10):3616–3624. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thorns C., Kuba J., Bernard V., Senft A., Szymczak S., Feller A.C., Bernd H.W. Deregulation of a distinct set of microRNAs is associated with transformation of gastritis into MALT lymphoma. Virchows Arch. 2012;460(4):371–377. doi: 10.1007/s00428-012-1215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu T.Y., Chen S.U., Kuo S.H., Cheng A.L., Lin C.W. E2A-positive gastric MALT lymphoma has weaker plasmacytoid infiltrates and stronger expression of the memory B-cell-associated miR-223: possible correlation with stage and treatment response. Mod. Pathol. 2010;23(11):1507–1517. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bouteloup M., Verney A., Rachinel N., Callet-Bauchu E., Ffrench M., Coiffier B., Magaud J.P., Berger F., Salles G.A., Traverse-Glehen A. MicroRNA expression profile in splenic marginal zone lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 2012;156(2):279–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ballabio E., Mitchell T., van Kester M.S., Taylor S., Dunlop H.M., Chi J., Tosi I., Vermeer M.H., Tramonti D., Saunders N.J., Boultwood J., Wainscoat J.S., Pezzella F., Whittaker S.J., Tensen C.P., Hatton C.S., Lawrie C.H. MicroRNA expression in Sezary syndrome: identification, function, and diagnostic potential. Blood. 2010;116(7):1105–1113. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-256719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.(a) Qin Y., Buermans H.P., van Kester M.S., van der Fits L., Out-Luiting J.J., Osanto S., Willemze R., Vermeer M.H., Tensen C.P. Deep-sequencing analysis reveals that the miR-199a2/214 cluster within DNM3os represents the vast majority of aberrantly expressed microRNAs in SA(c)zary syndrome. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2012;132(5):1520–1522. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Narducci M.G., Arcelli D., Picchio M.C., Lazzeri C., Pagani E., Sampogna F., Scala E., Fadda P., Cristofoletti C., Facchiano A., Frontani M., Monopoli A., Ferracin M., Negrini M., Lombardo G.A., Caprini E., Russo G. MicroRNA profiling reveals that miR-21, miR486 and miR-214 are upregulated and involved in cell survival in SA(c)zary syndrome. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e151. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cristofoletti C., Picchio M.C., Lazzeri C., Tocco V., Pagani E., Bresin A., Mancini B., Passarelli F., Facchiano A., Scala E., Lombardo G.A., Cantonetti M., Caprini E., Russo G., Narducci M.G. Comprehensive analysis of PTEN status in Sezary syndrome. Blood. 2013;122(20):3511–3520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-510578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.van Kester M.S., Ballabio E., Benner M.F., Chen X.H., Saunders N.J., van der Fits L., van Doorn R., Vermeer M.H., Willemze R., Tensen C.P., Lawrie C.H. miRNA expression profiling of mycosis fungoides. Mol. Oncol. 2011;5(3):273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Benner M.F., Ballabio E., van Kester M.S., Saunders N.J., Vermeer M.H., Willemze R., Lawrie C.H., Tensen C.P. Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma shows a distinct miRNA expression profile and reveals differences from tumor-stage mycosis fungoides. Exp. Dermatol. 2012;21(8):632–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2012.01548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ralfkiaer U., Hagedorn P.H., Bangsgaard N., Lovendorf M.B., Ahler C.B., Svensson L., Kopp K.L., Vennegaard M.T., Lauenborg B., Zibert J.R., Krejsgaard T., Bonefeld C.M., Sokilde R., Gjerdrum L.M., Labuda T., Mathiesen A.M., Gronbaek K., Wasik M.A., Sokolowska-Wojdylo M., Queille-Roussel C., Gniadecki R., Ralfkiaer E., Geisler C., Litman T., Woetmann A., Glue C., Ropke M.A., Skov L., Odum N. Diagnostic microRNA profiling in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). Blood. 2011;118(22):5891–5900. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-358382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bezman N.A., Chakraborty T., Bender T., Lanier L.L. miR-150 regulates the development of NK and iNKT cells. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208(13):2717–2731. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ghisi M., Corradin A., Basso K., Frasson C., Serafin V., Mukherjee S., Mussolin L., Ruggero K., Bonanno L., Guffanti A., De Bellis G., Gerosa G., Stellin G., D'Agostino D.M., Basso G., Bronte V., Indraccolo S., Amadori A., Zanovello P. Modulation of microRNA expression in human T-cell development: targeting of NOTCH3 by miR-150. Blood. 2011;117(26):7053–7062. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-326629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.ManfA" V., Biskup E., Rosbjerg A., Kamstrup M., Skov A.G., Lerche C.M., Lauenborg B.T., Odum N., Gniadecki R. miR-122 regulates p53/Akt signalling and the chemotherapy-induced apoptosis in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Calin G.A., Dumitru C.D., Shimizu M., Bichi R., Zupo S., Noch E., Aldler H., Rattan S., Keating M., Rai K., Rassenti L., Kipps T., Negrini M., Bullrich F., Croce C.M. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99(24):15524–15529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Takamizawa J., Konishi H., Yanagisawa K., Tomida S., Osada H., Endoh H., Harano T., Yatabe Y., Nagino M., Nimura Y., Mitsudomi T., Takahashi T. Reduced expression of the let-7 microRNAs in human lung cancers in association with shortened postoperative survival. Cancer Res. 2004;64(11):3753–3756. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lu J., Getz G., Miska E.A., Alvarez-Saavedra E., Lamb J., Peck D., Sweet-Cordero A., Ebert B.L., Mak R.H., Ferrando A.A., Downing J.R., Jacks T., Horvitz H.R., Golub T.R. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435(7043):834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Swerdlow S., Campo E., Harris N.L., Jaffe E.S., Pileri S.A., Stein H., Thiele J., Vardiman J.W. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissue. 4th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Connors J.M. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the clinician's perspective--a view from the receiving end. Mod. Pathol. 2013;26(Suppl. 1):S111–S118. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lenz G., Davis R.E., Ngo V.N., Lam L., George T.C., Wright G.W., Dave S.S., Zhao H., Xu W., Rosenwald A., Ott G., Muller-Hermelink H.K., Gascoyne R.D., Connors J.M., Rimsza L.M., Campo E., Jaffe E.S., Delabie J., Smeland E.B., Fisher R.I., Chan W.C., Staudt L.M. Oncogenic CARD11 mutations in human diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Science. 2008;319(5870):1676–1679. doi: 10.1126/science.1153629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lawrie C.H., Larrea E., Larrinaga G., Goicoechea I., Arestin M., Fernandez-Mercado M., Hes O., Cáceres F., Manterola L., López, J.I. Targeted next-generation sequencing and non-coding RNA expression analysis of clear cell papillary renal cell carcinoma suggests distinct pathological mechanisms from other renal tumour subtypes. J. Pathol. 2014;232(1):32–42. doi: 10.1002/path.4296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.(a) Pathak A.K., Bhutani M., Kumar S., Mohan A., Guleria R. Circulating cell-free DNA in plasma/serum of lung cancer patients as a potential screening and prognostic tool. Clin. Chem. 2006;52(10):1833–1842. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.062893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Anker P., Mulcahy H., Stroun M. Circulating nucleic acids in plasma and serum as a noninvasive investigation for cancer: time for large-scale clinical studies? Int. J. Cancer. 2003;103(2):149–152. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Duttagupta R., Jiang R., Gollub J., Getts R.C., Jones K.W. Impact of cellular miRNAs on circulating miRNA biomarker signatures. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mitchell P.S., Parkin R.K., Kroh E.M., Fritz B.R., Wyman S.K., Pogosova-Agadjanyan E.L., Peterson A., Noteboom J., O'Briant K.C., Allen A., Lin D.W., Urban N., Drescher C.W., Knudsen B.S., Stirewalt D.L., Gentleman R., Vessella R.L., Nelson P.S., Martin D.B., Tewari M. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105(30):10513–10518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804549105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lawrie C.H. MicroRNA expression in lymphoma. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2007;7(9):1363–1374. doi: 10.1517/14712598.7.9.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lawrie C.H., Gal S., Dunlop H.M., Pushkaran B., Liggins A.P., Pulford K., Banham A.H., Pezzella F., Boultwood J., Wainscoat J.S., Hatton C.S., Harris A.L. Detection of elevated levels of tumour-associated microRNAs in serum of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 2008;141(5):672–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen W., Wang H., Chen H., Liu S., Lu H., Kong D., Huang X., Kong Q., Lu Z. Clinical significance and detection of microRNA-21 in serum of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in Chinese population. Eur. J. Haematol. 2014;92(5):407–412. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fang C., Zhu D.X., Dong H.J., Zhou Z.J., Wang Y.H., Liu L., Fan L., Miao K.R., Liu P., Xu W., Li J.Y. Serum microRNAs are promising novel biomarkers for diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Ann. Hematol. 2012;91(4):553–559. doi: 10.1007/s00277-011-1350-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ohyashiki K., Umezu T., Yoshizawa S., Ito Y., Ohyashiki M., Kawashima H., Tanaka M., Kuroda M., Ohyashiki J.H. Clinical impact of down-regulated plasma miR-92a levels in non-Hodgkin ?(tm)s lymphoma. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e16408. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.(a) Yoshizawa S., Ohyashiki J.H., Ohyashiki M., Umezu T., Suzuki K., Inagaki A., Iida S., Ohyashiki K. Downregulated plasma miR-92a levels have clinical impact on multiple myeloma and related disorders. Blood Cancer J. 2012;2(1):e53. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2011.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tanaka M., Oikawa K., Takanashi M., Kudo M., Ohyashiki J., Ohyashiki K., Kuroda M. Down-regulation of miR-92 in human plasma is a novel marker for acute leukemia patients. PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jones K., Nourse J.P., Keane C., Bhatnagar A., Gandhi M.K. Plasma microRNA are disease response biomarkers in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014;20(1):253–264. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Guo H.Q., Huang G.L., Guo C.C., Pu X.X., Lin T.Y. Diagnostic and prognostic value of circulating miR-221 for extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Dis. Markers. 2010;29(5):251–258. doi: 10.1155/2010/474692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Alencar A.J., Malumbres R., Kozloski G.A., Advani R., Talreja N., Chinichian S., Briones J., Natkunam Y., Sehn L.H., Gascoyne R.D., Tibshirani R., Lossos I.S. MicroRNAs are independent predictors of outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with R-CHOP. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17(12):4125–4135. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Iqbal J., Shen Y., Huang X., Liu Y., Wake L., Liu C., Deffenbacher K., Lachel C.M., Wang C., Rohr J., Guo S., Smith L.M., Wright G., Bhagavathi S., Dybkaer K., Fu K., Greiner T.C., Vose J.M., Jaffe E., Rimsza L., Rosenwald A., Ott G., Delabie J., Campo E., Braziel R.M., Cook J.R., Tubbs R.R., Armitage J.O., Weisenburger D.D., Staudt L.M., Gascoyne R.D., McKeithan T.W., Chan W.C. Global microRNA expression profiling uncovers molecular markers for classification and prognosis in aggressive B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125(7):1137–1145. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-566778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bui T.V., Mendell J.T. Myc: Maestro of MicroRNAs. Genes Cancer. 2010;1(6):568–575. doi: 10.1177/1947601910377491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.(a) Di Martino M.T., Leone E., Amodio N., Foresta U., Lionetti M., Pitari M.R., Cantafio M.E., GullA A., Conforti F., Morelli E., Tomaino V., Rossi M., Negrini M., Ferrarini M., Caraglia M., Shammas M.A., Munshi N.C., Anderson K.C., Neri A., Tagliaferri P., Tassone P. Synthetic miR-34a mimics as a novel therapeutic agent for multiple myeloma: in vitro and in vivo evidence. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18(22):6260–6270. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Medina P.P., Nolde M., Slack F.J. OncomiR addiction in an in vivo model of microRNA-21-induced pre-B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 2010;467(7311):86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature09284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Akinc A., Zumbuehl A., Goldberg M., Leshchiner E.S., Busini V., Hossain N., Bacallado S.A., Nguyen D.N., Fuller J., Alvarez R., Borodovsky A., Borland T., Constien R., de Fougerolles A., Dorkin J.R., Narayanannair Jayaprakash K., Jayaraman M., John M., Koteliansky V., Manoharan M., Nechev L., Qin J., Racie T., Raitcheva D., Rajeev K.G., Sah D.W., Soutschek J., Toudjarska I., Vornlocher H.P., Zimmermann T.S., Langer R., Anderson D.G. A combinatorial library of lipid-like materials for delivery of RNAi therapeutics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26(5):561–569. doi: 10.1038/nbt1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen W., Wang H., Chen H., Liu S., Lu H., Kong D., Huang X., Kong Q., Lu Z. Clinical significance and detection of microRNA-21 in serum of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in Chinese population. Eur. J. Haematol. 2014;92(5):407–412. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Knudsen S., Hother C., Gronbaek K., Jensen T., Hansen A., Mazin W., Dahlgaard J., MA,ller M.B., RalfkiA r E., Brown Pde.N. Development and blind clinical validation of a microRNA based predictor of response to treatment with R-CHO(E)P in DLBCL. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0115538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sanchez-Espiridion B., Martin-Moreno A.M., Montalban C., Figueroa V., Vega F., Younes A., Medeiros L.J., Alves F.J., Canales M., Estevez M., Menarguez J., Sabin P., Ruiz-Marcellan M.C., Lopez A., Sanchez-Godoy P., Burgos F., Santonja C., Lopez J.L., Piris M.A., Garcia J.F. MicroRNA signatures and treatment response in patients with advanced classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 2013;162(3):336–347. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ballabio E., Mitchell T., van Kester M.S., Taylor S., Dunlop H.M., Chi J., Tosi I., Vermeer M.H., Tramonti D., Saunders N.J., Boultwood J., Wainscoat J.S., Pezzella F., Whittaker S.J., Tensen C.P., Hatton C.S., Lawrie C.H. MicroRNA expression in Sezary syndrome: identification, function, and diagnostic potential. Blood. 2010;116(7):1105–1113. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-256719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]