Abstract

Purpose of review

Hypertension is a leading cause of cardiovascular and renal morbidity and mortality. Genome wide association studies identified a single nucleotide polymorphism in the gene SH2B3 encoding the lymphocyte adaptor protein, LNK, but until recently, little was known about how LNK contributes to hypertension. This review summarizes recent work highlighting a central role for LNK in inflammation and hypertension.

Recent findings

Using a systems biology approach that integrates genomic data with whole blood transcriptomic data and network modeling, LNK/SH2B3 was identified as a key driver gene for hypertension in humans. LNK is an intracellular adaptor protein expressed predominantly in hematopoietic and endothelial cells that negatively regulates cell proliferation and cytokine signaling. Genetic animal models with deletion or mutation of LNK revealed an important role for LNK in renal and vascular inflammation, glomerular injury, oxidative stress, interferon gamma (IFNγ) production, and hypertension. Bone marrow transplantation experiments revealed that LNK in hematopoietic cells is primarily responsible for blood pressure regulation.

Summary

LNK/SH2B3 is a key driver gene for human hypertension, and alteration of LNK in animal models has a profound effect on inflammation and hypertension. Thus, LNK is a potential therapeutic target for this disease and its devastating consequences.

Keywords: LNK, SH2B3, hypertension, inflammation, interferon gamma (IFNγ)

Introduction

Inflammatory cells have been observed in the kidneys of hypertensive animals and humans for almost half a century, yet we are only now starting to understand their importance. In the 1960s, Okuda and Grollman showed that transfer of lymph node cells from rats with renal infarction into normal recipient rats induced hypertension [1]. This was the first evidence of a soluble immune factor inducing hypertension. In recent years, through the development of sophisticated tools to study and manipulate the immune system in experimental animals, it is clear that cells of the innate and adaptive immune system play critical roles at least in experimental hypertension. Guzik et al. showed that recombination activating gene 1 deficient mice, which lack both T and B lymphocytes, develop blunted hypertension in response to angiotensin II infusion with the hypertensive response being restored by adoptive transfer of T lymphocytes [2]. Recently Chan et al. demonstrated that B cells also play an important role in hypertension and hypertensive end-organ damage [3]. Wenzel et al. and Kirabo et al. identified a critical role for antigen presenting cells such as monocytes and dendritic cells in hypertension and vascular dysfunction [4, *5]. Kirabo et al. showed that isoketals (a lipid oxidation product) accumulate in dendritic cells in experimental and human hypertension and that isoketal-modified proteins may serve as neoantigens to activate T cells in hypertension. In the past decade, we and others have shown that pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 17 (IL-17), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha, interferon gamma (IFNγ), and IL-6 play critical roles in hypertension and that inhibition or genetic deletion of these cytokines results in blunted hypertension and reduced end-organ damage [*6]. For a more comprehensive review of the role of innate and adaptive immunity in hypertension, see McMaster et al. [*6].

Genome wide association studies for hypertension identified a polymorphism in LNK/SH2B3

Epidemiological studies in twins and in families from three generations of Framingham Heart Study participants revealed that blood pressure has a substantial heritable component ranging from 33-57% [7-9]. In an attempt to elucidate the genetic components of hypertension, multiple genome wide association studies (GWAS) have been conducted over the past several years [10, 11]. A recent meta-analysis of GWAS data in 200,000 individuals of European descent revealed that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 29 loci attained genome-wide significance for systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, or both [12]. One of these loci, the SH2B3 gene that encodes the lymphocyte adaptor protein, LNK, was significantly associated with both systolic and diastolic blood pressure [10]. LNK is not specific to lymphocytes but rather is expressed in all hematopoietic lineages and some non-hematopoietic cells, particularly endothelial cells [13]. A non-synonymous SNP in exon 3 of LNK, rs3184504, leading to an arginine to tryptophan substitution in amino acid 262 (R262W) was found to be associated with hypertension and myocardial infarction as well as multiple autoimmune disorders including type 1 diabetes, celiac disease, and multiple sclerosis [13].

Systems biology identifies LNK/SH2B3 as a key driver gene for hypertension

Single gene SNP analyses provide only one dimension of genetic information, and unfortunately, even the top loci identified by GWAS in aggregate explain only ~1% of blood pressure (BP) variability. Recognizing that genes, rather than working in isolation, interact with other genes in complex regulatory networks, Levy and colleagues designed a novel systems biology framework to integrate gene expression (transcriptomic) data with blood pressure GWAS and cellular network modeling to determine if perturbations in gene subnetworks are linked to hypertension [*14]. They used genetic and transcriptomic data (>17,000 measured gene transcripts isolated from whole blood) from 3,679 Framingham Heart Study participants who were not receiving antihypertensive drug treatment. This analysis further supported an important role for SH2B3 in hypertension, identifying it as a key driver gene in this disease process. The rs3184504 SNP that was associated with blood pressure in GWAS was found to be associated with 19 genes in a cis or trans manner. The LNK/SH2B3-derived protein-protein interaction network consisted of 362 genes (41 of which are known blood pressure related genes). Of note, this network was enriched for genes involved in intracellular signaling, T cell activation, and T cell differentiation. To validate the accuracy of these findings, we used a mouse model of LNK deficiency and performed RNA sequencing of the entire transcriptome in whole blood from wild type and LNK−/− mice. At a false discovery rate of <0.05, there were 2,240 differentially expressed genes, supporting a large-scale perturbation of the transcriptome in LNK−/− mice. These gene signatures showed significant overlap with the genes identified by the in silico model and were enriched for genes involved in inflammation and T cell activation as predicted by the SH2B3 subnetworks [*14].

Levy and colleagues subsequently performed a meta-analysis of results from 6 studies of global gene expression profiles in whole blood from 7017 individuals who were not receiving antihypertensive drug treatment and identified 34 genes that were differentially expressed in relation to BP [*15]. The top BP signature genes in aggregate explain 5-9% of BP variability. Of note, the rs3184504 SNP in LNK/SH2B3 was found to be a trans regulator of the expression of 6 of the transcripts associated with BP (FOS, MYADM, PP1R15A, TAGAP, S100A10, and FGBP2).

Structure and function of LNK/SH2B3

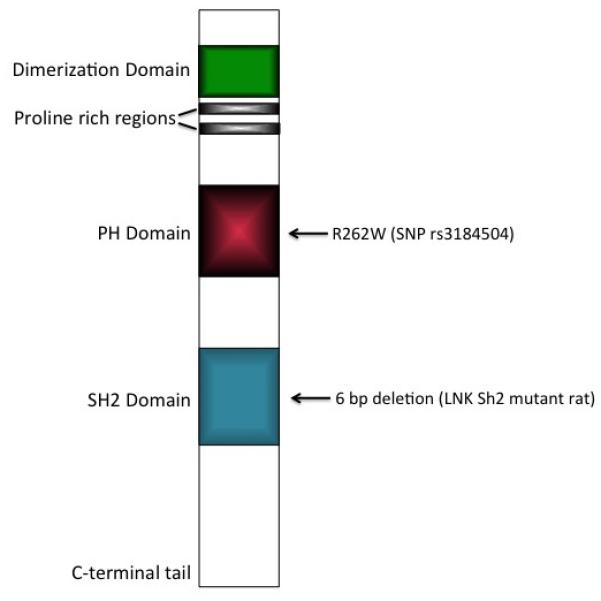

LNK is composed of four functional domains: a dimerization domain, a proline rich region, a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, and a Src homology 2 (SH2) domain (Figure 1). The PH domain recognizes phosphotidylinositol lipids within biological membranes and is thought to target LNK to the cell membrane to facilitate its function as a signal transduction regulator. The rs3184504 SNP that results in an arginine to tryptophan substitution at amino acid 262 (R262W) is located in the PH domain. The SH2 domain represents the largest class of phosphotyrosine-selective recognition domains and generally serves to target kinases to their substrates [13].

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the structural organization of LNK/SH2B3 showing the location of the GWAS identified single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP rs3184504), leading to an arginine to tryptophan substitution at amino acid 262 (R262W) and the 6 bp in frame deletion created by Rudemiller et al [**17]. PH: Pleckstrin homology domain; SH2: Src homology 2 domain.

As a member of the SH2B family of adaptor proteins, LNK influences a variety of signaling pathways mediated by Janus kinase and receptor tyrosine kinases. Initially described as a regulator of hematopoiesis and lymphocyte differentiation, LNK is now known to play key roles in regulating growth factor and cytokine receptor-mediated signaling in both hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells. In endothelial cells, LNK is a negative regulator of TNF signaling. In both platelets and endothelial cells, LNK modulates integrin signaling and actin cytoskeleton organization to impact cell adhesion, migration, and thrombosis. For a detailed review of LNK function and signaling, see Devalliere and Charreau [13].

LNK/SH2B3 regulates blood pressure and IFNγ production

Using two different animal models and approaches to disrupt LNK signaling, we [*16] and Rudemiller et al. [**17] confirmed that LNK indeed regulates blood pressure and renal inflammation. We studied mice with a genetic deletion of LNK and induced hypertension using angiotensin II infusion. Rudemiller et al. created Dahl salt-sensitive rats with a 6-bp in frame deletion within a highly conserved portion of the Sh2 domain and induced hypertension with a 4% salt diet. It should be noted that this mutation does not recapitulate the GWAS identified SNP which is in the PH domain (Figure 1). Rather, this mutation is predicted to alter a phosphotyrosine-peptide binding pocket in the Sh2 domain [**17]. At baseline, there is no change in blood pressure between LNK deficient and wild type mice. However, loss of LNK severely exacerbates angiotensin II induced hypertension. When infused with a subpressor dose of angiotensin II that normally does not raise blood pressure in wild type mice, LNK−/− mice reach blood pressures of 160-170 mmHg. Kidneys of LNK−/− mice exhibit greater baseline levels of inflammation, oxidative stress, and glomerular injury (as measured by albuminuria) compared to wild type animals, and these parameters are further exacerbated by angiotensin II infusion. LNK−/− mice also exhibit enhanced vascular inflammation, reduced aortic nitric oxide levels, and impaired endothelial-dependent relaxation (Figure 2) [*16]. On the other hand, mutation of the Sh2 domain of LNK results in attenuation of Dahl salt-sensitive hypertension, albuminuria, and renal inflammation with no effect on vascular reactivity [**17]. In both cases, bone marrow transplantation from LNK deleted or mutated mice into wild type recipients, resulted in hypertension exacerbation or protection, respectively. This demonstrates that modulation of LNK function in immune cells is primarily responsible for blood pressure control. Interestingly, bone marrow transplantation from wild type mice into LNK−/− recipients did result in an intermediate hypertensive response to angiotensin II, suggesting that LNK in somatic cells also contributes to blood pressure regulation.

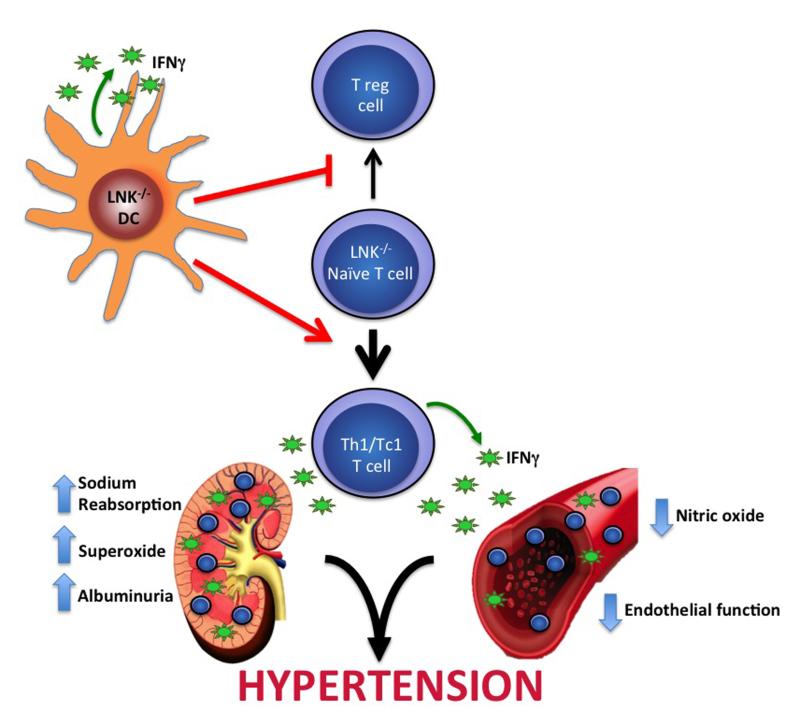

Figure 2.

Proposed model for how LNK deficiency exacerbates hypertension and end-organ dysfunction. Loss of LNK in dendritic cells (DC) promotes polarization of naïve T cells into IFNγ producing Th1/Tc1 cells rather than the anti-inflammatory T regulatory (T reg) cells. LNK deficiency results in increased accumulation of Th1/Tc1 cells in organs such as the kidney and blood vessel. Increased inflammation and IFNγ production lead to increased sodium reabsorption, superoxide production, and albuminuria in the kidney and decreased nitric oxide and impaired endothelial dependent relaxation in vessels and ultimately hypertension.

At first glance, the findings from the two models may seem disparate, but it is likely related to the method used to disrupt LNK function. As a key driver gene, LNK regulates the expression of a number of other genes. As mentioned above, LNK−/− mice had perturbations in over 2,000 transcripts compared to wild type mice. LNK also interacts with a number of binding partners, primarily through the Sh2 domain. Thus, while the first model represents a complete loss of function of LNK, the second model represents an “alteration” of function of LNK. Importantly, these two models provide proof of principle that modulation of LNK function in immune cells can regulate blood pressure and the associated inflammation and end-organ damage.

To determine how LNK modulates inflammation, we examined T cell subsets and cytokine production from splenic T cells of wild type and LNK−/− mice infused with vehicle or angiotensin II. The LNK−/− splenic T cells produced significantly more IFNγ at baseline and following angiotensin II infusion, consistent with skewing of these cells towards a Th1 (CD4+) and Tc1 (CD8+) phenotype. Intracellular staining for IFNγ in spleen and kidney revealed increased accumulation of Th1 cells, and particularly Tc1 cells, in LNK deficient animals [*16]. Interestingly, the same LNK polymorphism that is associated with hypertension is also associated with celiac disease. A recent study by Katayama et al. [18] demonstrated that LNK deficient mice had intestinal pathology resembling human celiac disease that was associated with enhanced IFNγ producing CD8+ T cells in the spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes, and intestinal lamina propria.

LNK in dendritic cells regulates T cell production of IFNγ

Dendritic cells (DCs) are potent antigen presenting cells that play critical roles in the immune response to pathogens by activating and polarizing T cells. Recently, Kirabo et al. [*5] identified a novel pathway by which DCs promote hypertension through presentation of isoketal-modified proteins to T cells resulting in T cell activation and proliferation. An elegant study by Mori et al. [**19] linked LNK with DC function and T cell polarization. The authors showed that LNK is expressed in DCs and that LNK−/− mice exhibit increased numbers of DCs in the spleen and lymph nodes. Compared to wild type DCs, LNK−/− DCs produce more IFNγ and promote differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into IFNγ producing Th1 cells even under conditions in which wild type DCs promote the induction of anti-inflammatory T regulatory (Treg) cells. Tregs have been shown to blunt angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular injury [20]. Interestingly, in the LNK Sh2 domain mutated mice, Rudemiller et al. [**17] detected an increased percentage of circulating and splenic Treg cells which could, in part, explain the blunted blood pressure response in these mice. Thus, LNK in DCs may regulate blood pressure by modulating the balance of pro-inflammatory Th1/Tc1 cells and anti-inflammatory Treg cells (Figure 2).

IFNγ regulates blood pressure and renal dysfunction

Since LNK deficiency enhances IFNγ production, could this explain the mechanism by which loss of LNK leads to hypertension susceptibility? We and others have investigated the effect of IFNγ signaling on blood pressure and end-organ dysfunction in recent years using several different animal models with somewhat mixed results. Garcia et al. [21] found that IFNγ deficiency protected against hypertension in a mouse model of uninephrectomy combined with aldosterone infusion and salt feeding. However, these mice developed more left ventricular hypertrophy and worse diastolic dysfunction. We found that IFNγ deficient mice developed blunted hypertension in response to angiotensin II infusion [*16]. Marko et al. [22] studied mice with IFNγ receptor 1 deficiency and found that although there was no change in blood pressure following high dose angiotensin II infusion in these mice compared to wild type mice, IFNγ receptor 1 deficient mice developed blunted cardiac hypertrophy and decreased renal inflammation and tubulointerstitial damage, suggesting that blockade of IFNγ signaling alleviates the end-organ effects of hypertension.

Renal salt handling is a critical regulator of blood pressure. Kamat et al. [*23] recently examined the effect of IFNγ on renal sodium transport. Wild type mice exhibit a significant decrease in the rate of sodium excretion when challenged with a saline bolus following 10 days of angiotensin II infusion compared to baseline. In response to the same saline challenge, IFNγ deficient mice excreted significantly more of the injected sodium at baseline, and their rate of sodium excretion did not change following 10 days of angiotensin II infusion. This data suggests that IFNγ mediates the kidney’s anti-natriuretic response to angiotensin II. Renal sodium transporter profiling performed at baseline and after 2 weeks of angiotensin II infusion demonstrated that IFNγ−/− mice exhibited a decrease in abundance of the proximal tubule sodium hydrogen exchanger 3 (NHE3) after angiotensin II infusion with no change in NHE3 abundance detected in wild type mice. Reduced NHE3 expression is an important mechanism for pressure natriuresis. In the distal nephron, angiotensin II infusion increased abundance of the phosphorylated forms of the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter and the Na-Cl cotransporter in wild type but not IFNγ−/− mice. In keeping with this, Satou et al. [24] showed that IFNγ can increase angiotensinogen production from renal proximal tubule cells, thereby stimulating the intrarenal renin angiotensin system (RAS). Locally produced angiotensin II can promote salt and water reabsorption through effects on proximal and distal sodium transporters [*6]. Taken together, these data suggest that IFNγ, either directly or through activation of the intrarenal RAS, interferes with the pressure natriuretic response in the proximal tubule and promotes distal tubule sodium reabsorption.

Conclusion and Future Directions

A critical role for LNK signaling in hypertension has recently been elucidated using genetic animal models containing a deletion or mutation of LNK. Loss of LNK leads to profound inflammation in renal and vascular tissues as well as increased IFNγ production from DCs and T lymphocytes. LNK in DCs may regulate the balance between pro-inflammatory Th1/Tc1 cells and anti-inflammatory Treg cells. IFNγ likely mediates, at least in part, the effect of LNK deficiency on hypertensive end-organ damage (Figure 2).

The discovery and validation of LNK/SH2B3 as a key regulator of blood pressure is a prime example of the power of systems biology to identify novel genes and pathways that cause human disease. However, even the top BP signature genes in aggregate only explained 5-9% of BP variability. Thus, we are still missing a component of BP heritability that may lie in the epigenome or microRNAs. In the future, additional genomic data such as DNA methylation signatures and microRNA expression profiling can be integrated with GWAS and transcriptomic data to further define the genetics of hypertension well beyond single nucleotide polymorphisms. In the meantime, extensive research is still needed to understand how LNK in different cell types (dendritic cells, T lymphocytes, endothelial cells, etc.) contributes to normal physiology as well as pathophysiological alterations and disease. We need to delineate the binding partners and signaling pathways through which LNK mediates hypertension and renal/vascular dysfunction. Another important question is what is the effect of the human missense SNP in the PH domain of SH2B3 on LNK function? Is this a functional SNP or is it a marker of other alterations in LNK or neighboring genes that are inherited in linkage disequilibrium? Since the PH domain is predicted to target LNK to the cell membrane, a missense mutation in the PH domain would be predicted to alter subcellular localization, but this is yet to be determined. The Sh2 domain mutant studies demonstrate that LNK function can be modulated in a beneficial way to reduce hypertension and end-organ damage. Since LNK has been linked to multiple autoimmune as well as cardiovascular disorders, novel therapeutic approaches to modulate LNK signaling could have profound therapeutic benefit in a myriad of inflammatory diseases.

Key points.

Genome-wide association studies identified a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP rs3184504) that results in a missense mutation in the pleckstrin homology domain of LNK/SH2B3 to be associated with hypertension.

A systems biology approach that integrates genomic data with whole blood transcriptomic data and network modeling revealed that SH2B3 was a top key driver gene for hypertension in humans.

LNK is an intracellular adaptor protein expressed in all hematopoietic lineages and some non-hematopoietic cells, particularly endothelial cells, and negatively regulates cell proliferation and cytokine signaling.

Genetic animal models with deletion of LNK or mutation in the Src homology 2 domain of LNK revealed an important role for LNK in renal and vascular inflammation, glomerular injury, oxidative stress, interferon gamma (IFNγ) production, and hypertension.

LNK is potentially a novel therapeutic target for hypertension as well as other cardiovascular and autoimmune disorders.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Drs. Daniel Levy and Tianxiao Huan for critically reviewing the manuscript.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by an NIH T32 training grant to B. Dale, an NIH NHLBI K08 grant to M.S. Madhur, and a Gilead Cardiovascular Scholars Award to M.S. Madhur.

Funding sources:

NIH T32 (Dale), NIH K08 (Madhur), Gilead CV Scholars Award (Madhur)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

M.S. Madhur is currently receiving a grant from Gilead Sciences, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Okuda T, Grollman A. Passive transfer of autoimmune induced hypertension in the rat by lymph node cells. Tex Rep Biol Med. 1967;25(2):257–64. Summer. PubMed PMID: 6040652. Epub 1967/01/01. eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, et al. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med. 2007 Oct 1;204(10):2449–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. PubMed PMID: 17875676. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2118469. Epub 2007/09/19. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan CT, Sobey CG, Lieu M, Ferens D, Kett MM, Diep H, et al. Obligatory Role for B Cells in the Development of Angiotensin II-Dependent Hypertension. Hypertension. 2015 Sep;:8. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05779. PubMed PMID: 26351030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wenzel P, Knorr M, Kossmann S, Stratmann J, Hausding M, Schuhmacher S, et al. Lysozyme M-positive monocytes mediate angiotensin II-induced arterial hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Circulation. 2011 Sep 20;124(12):1370–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.034470. PubMed PMID: 21875910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *5.Kirabo A, Fontana V, de Faria AP, Loperena R, Galindo CL, Wu J, et al. DC isoketal-modified proteins activate T cells and promote hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2014 Oct 1;124(10):4642–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI74084. PubMed PMID: 25244096. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4220659. This manuscript describes a novel pathway by which dendritic cells become activated and promote T cell activation in hypertension. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *6.McMaster WG, Kirabo A, Madhur MS, Harrison DG. Inflammation, immunity, and hypertensive end-organ damage. Circ Res. 2015 Mar 13;116(6):1022–33. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303697. PubMed PMID: 25767287. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4535695. This is a comprehensive review of the role of inflammatory cytokines in hypertension and hypertensive end-organ damage. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jermendy G, Horvath T, Littvay L, Steinbach R, Jermendy AL, Tarnoki AD, et al. Effect of genetic and environmental influences on cardiometabolic risk factors: a twin study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011;10:96. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-10-96. PubMed PMID: 22050728. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3219730. Epub 2011/11/05. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell GF, DeStefano AL, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Chen MH, Vasan RS, et al. Heritability and a genome-wide linkage scan for arterial stiffness, wave reflection, and mean arterial pressure: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2005 Jul 12;112(2):194–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.530675. PubMed PMID: 15998672. Epub 2005/07/07. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy D, DeStefano AL, Larson MG, O'Donnell CJ, Lifton RP, Gavras H, et al. Evidence for a gene influencing blood pressure on chromosome 17. Genome scan linkage results for longitudinal blood pressure phenotypes in subjects from the framingham heart study. Hypertension. 2000 Oct 36;4:477–83. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.4.477. PubMed PMID: 11040222. Epub 2000/10/21. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy D, Ehret GB, Rice K, Verwoert GC, Launer LJ, Dehghan A, et al. Genome-wide association study of blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Genet. 2009 Jun;41(6):677–87. doi: 10.1038/ng.384. PubMed PMID: 19430479. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2998712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newton-Cheh C, Johnson T, Gateva V, Tobin MD, Bochud M, Coin L, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight loci associated with blood pressure. Nat Genet. 2009 Jun;41(6):666–76. doi: 10.1038/ng.361. PubMed PMID: 19430483. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2891673. Epub 2009/05/12. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International Consortium for Blood Pressure Genome-Wide Association S. Ehret GB, Munroe PB, Rice KM, Bochud M, Johnson AD, et al. Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk. Nature. 2011 Oct 6;478(7367):103–9. doi: 10.1038/nature10405. PubMed PMID: 21909115. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3340926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devalliere J, Charreau B. The adaptor Lnk (SH2B3): an emerging regulator in vascular cells and a link between immune and inflammatory signaling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011 Nov 15;82(10):1391–402. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.06.023. PubMed PMID: 21723852. Epub 2011/07/05. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *14.Huan T, Meng Q, Saleh MA, Norlander AE, Joehanes R, Zhu J, et al. Integrative network analysis reveals molecular mechanisms of blood pressure regulation. Molecular systems biology. 2015 Jan;11(1):799. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145399. PubMed PMID: 25882670. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4422556. This manuscript describes a novel systems biology approach to identify key driver genes for hypertension and demonstrates that LNK/SH2B3 is one of the top key driver genes for this disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *15.Huan T, Esko T, Peters MJ, Pilling LC, Schramm K, Schurmann C, et al. A meta-analysis of gene expression signatures of blood pressure and hypertension. PLoS Genet. 2015 Mar;11(3):e1005035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005035. PubMed PMID: 25785607. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4365001. This meta-analysis identified 34 genes that were differentially expressed in relation to blood pressure (BP). The top BP signature genes in aggregate explain 5-9% of BP variability. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *16.Saleh MA, McMaster WG, Wu J, Norlander AE, Funt SA, Thabet SR, et al. Lymphocyte adaptor protein LNK deficiency exacerbates hypertension and end-organ inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2015 Feb;:9. doi: 10.1172/JCI76327. PubMed PMID: 25664851. This is the first experimental study demonstrating that loss of LNK promotes hypertension and hypertensive end-organ damage. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **17.Rudemiller NP, Lund H, Priestley JR, Endres BT, Prokop JW, Jacob HJ, et al. Mutation of SH2B3 (LNK), a genome-wide association study candidate for hypertension, attenuates Dahl salt-sensitive hypertension via inflammatory modulation. Hypertension. 2015 May;65(5):1111–7. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04736. PubMed PMID: 25776069. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4412596. This study demonstrates that LNK can be altered in a beneficial way to blunt hypertension and renal inflammation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katayama H, Mori T, Seki Y, Anraku M, Iseki M, Ikutani M, et al. Lnk prevents inflammatory CD8 T-cell proliferation and contributes to intestinal homeostasis. Eur J Immunol. 2014 Feb;:17. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343883. PubMed PMID: 24536025. Epub 2014/02/19. Eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **19.Mori T, Iwasaki Y, Seki Y, Iseki M, Katayama H, Yamamoto K, et al. Lnk/SH2B3 controls the production and function of dendritic cells and regulates the induction of IFN-gamma-producing T cells. J Immunol. 2014 Aug 15;193(4):1728–36. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303243. PubMed PMID: 25024389. This study demonstrates that LNK in dendritic cells can influence T cell polarization and regulate the balance between pro-inflammatory Th1 cells and anti-inflammatory T regulatory cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barhoumi T, Kasal DA, Li MW, Shbat L, Laurant P, Neves MF, et al. T regulatory lymphocytes prevent angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular injury. Hypertension. 2011 Mar;57(3):469–76. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.162941. PubMed PMID: 21263125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia AG, Wilson RM, Heo J, Murthy NR, Baid S, Ouchi N, et al. Interferon-gamma ablation exacerbates myocardial hypertrophy in diastolic heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012 Sep 1;303(5):H587–96. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00298.2012. PubMed PMID: 22730392. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3468473. Epub 2012/06/26. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marko L, Kvakan H, Park JK, Qadri F, Spallek B, Binger KJ, et al. Interferon-gamma signaling inhibition ameliorates angiotensin II-induced cardiac damage. Hypertension. 2012 Dec;60(6):1430–6. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.199265. PubMed PMID: 23108651. Epub 2012/10/31. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *23.Kamat NV, Thabet SR, Xiao L, Saleh MA, Kirabo A, Madhur MS, et al. Renal transporter activation during angiotensin-II hypertension is blunted in interferon-gamma−/− and interleukin-17A−/− mice. Hypertension. 2015 Mar;65(3):569–76. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04975. PubMed PMID: 25601932. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4326622. This study demonstrates that interferon gamma regulates sodium reabsorption through renal proximal and distal sodium transporters. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Satou R, Miyata K, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Ingelfinger JR, Navar LG, Kobori H. Interferon-gamma biphasically regulates angiotensinogen expression via a JAK-STAT pathway and suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1) in renal proximal tubular cells. FASEB J. 2012 May;26(5):1821–30. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-195198. PubMed PMID: 22302831. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3336777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]