Abstract

Background

Previous studies have raised concerns that video-assisted thoracoscopic (VATS) lobectomy may compromise nodal evaluation. The advantages or limitations of robotic lobectomy have not been thoroughly evaluated.

Methods

Perioperative outcomes and survival of patients who underwent open versus minimally-invasive surgery (MIS [VATS and robotic]) lobectomy and VATS versus robotic lobectomy for clinical T1-2, N0 non-small cell lung cancer from 2010 to 2012 in the National Cancer Data Base were evaluated using propensity score matching.

Results

Of 30,040 lobectomies, 7,824 were VATS and 2,025 were robotic. After propensity score matching, when compared with the open approach (n = 9,390), MIS (n = 9,390) was found to have increased 30-day readmission rates (5% versus 4%, p < 0.01), shorter median hospital length of stay (5 versus 6 days, p < 0.01), and improved 2-year survival (87% versus 86%, p = 0.04). There were no significant differences in nodal upstaging and 30-day mortality between the two groups. After propensity score matching, when compared with the robotic group (n = 1,938), VATS (n = 1,938) was not significantly different from robotics with regard to nodal upstaging, 30-day mortality, and 2-year survival.

Conclusions

In this population-based analysis, MIS (VATS and robotic) lobectomy was used in the minority of patients for stage I non-small cell lung cancer. MIS lobectomy was associated with shorter length of hospital stay and was not associated with increased perioperative mortality, compromised nodal evaluation, or reduced short-term survival when compared with the open approach. These results suggest the need for broader implementation of MIS techniques.

Video-assisted thoracoscopic (VATS) lobectomy is associated with shorter chest tube duration, less pain, and shorter length of hospital stay compared with thoracotomy [1]. Despite the benefits associated with VATS lobectomy, the technique has not been universally used for a spectrum of reasons, including concerns that a VATS approach compromises the oncologic principles of anatomic resection and complete lymphadenectomy [2].

Robotic techniques may offer advantages over a VATS approach by providing a three-dimensional binocular view of tissue planes as well as better precision and maneuverability due to a greater degree of wrist rotation. A recent study of 302 robotic lobectomies suggested that the robotic approach had improved nodal upstaging when compared with the VATS approach [3]. The utilization of robotic technology may, however, be limited by the high associated cost [4, 5]. Questions have also been raised regarding the safety of robotic techniques when compared with VATS or open lobectomy, and a recent national study found that the robotic approach was associated with a higher rate of intraoperative injury when compared with the VATS approach [6].

Previous studies that have investigated the use of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) techniques have either been from high-volume single centers or have utilized databases that lacked oncologic or survival data or only included data from specialized thoracic surgeons. This study was undertaken to evaluate MIS lobectomy techniques using the population-based National Cancer Data Base (NCDB), which includes oncologic and survival data from a range of academic and community centers across the United States. The purpose of the study was to compare perioperative outcomes, nodal evaluation, and short-term survival between open and MIS (VATS and robotic) lobectomy and between VATS and robotic lobectomy for clinical T1-2, N0, M0 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Material and Methods

Data Source

The NCDB is jointly administered by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society, and is estimated to capture 70% of all newly diagnosed cases of cancer in the United States and Puerto Rico. The American College of Surgeons has executed a Business Associate Agreement which includes a data use agreement with each of its Commission on Cancer accredited hospitals. Clinical staging data for the population of interest is directly recorded in the NCDB using the American Joint Committee on Cancer seventh edition TNM classifications [7].

Study Design

This retrospective analysis was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board. All patients in the NCDB diagnosed with clinical T1-2, N0, M0 NSCLC from 2010 to 2012 were identified for inclusion, and patients undergoing lobectomy were then identified using Surgical Procedure of the Primary Site codes 30 and 33. Only patients with available data on surgical approach were included for analysis. Exclusion criteria included nonmalignant pathology and history of previous unrelated malignancy. The primary outcomes were pathologic nodal upstaging, 30-day mortality and readmission, hospital length of stay, lymph node retrieval, surgical margin positivity, and rates of conversion to open. Secondary outcome was overall survival. The years 2010 to 2012 were chosen for analysis because data on surgical approach were not available before 2010. Because survival data were not available for patients diagnosed in 2012, survival analysis only included patients from 2010 to 2011.

Statistical Analysis

Outcomes of surgical approach were evaluated using an intent-to-treat analysis. Differences in perioperative outcomes between surgical approaches were evaluated using a propensity-matched analysis of open versus minimally invasive (VATS and robotic) surgery and also as a propensity-matched analysis of VATS versus robotic lobectomy. Propensity scores were developed, defined as the probability of treatment with the MIS approach versus open or with the robotic approach versus VATS, conditional on age, sex, race, Charlson/Deyo comorbidity score, median census-tract education and income levels, TNM T-status, tumor size, use of induction chemoradiation, and facility type. Patients were then matched on propensity score using a 1:1 nearest neighbor matching algorithm (MatchIt: Nonparametric Preprocessing for Parametric Causal Inference). After matching, balance was assessed using standardized differences of means. Primary and secondary outcomes were compared after propensity-matching using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous measures and Pearson’s χ2 test for discrete variables. Differences in survival between groups were evaluated with two additional propensity-matched analyses of open versus MIS and VATS versus robotic, using the Kaplan-Meier method with log rank test. Survival analysis only included patients from years 2010 to 2011 because, as described above, survival data were not available for 2012. Survival was measured from time of diagnosis to time of death or last follow-up.

Model balance and diagnostics were assessed, and no major assumptions were violated. The p value of 0.05 was used to define statistical significance for all comparisons. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 3.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Use of MIS Versus Open Approaches

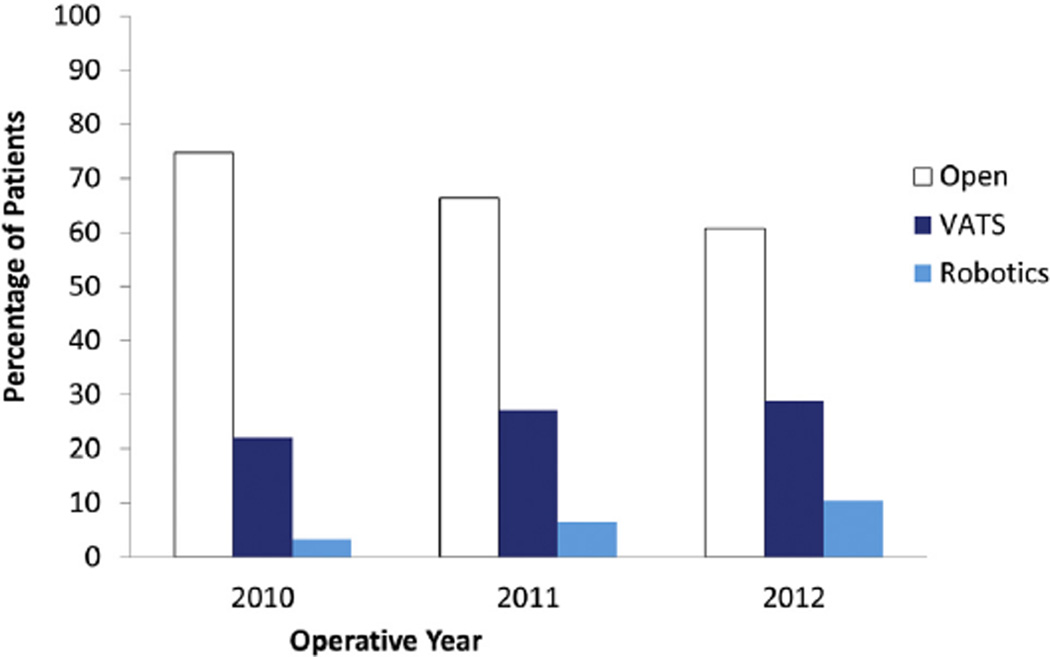

A minimally invasive approach was used in 9,849 (33%) of 30,040 patients in the NCDB who underwent lobectomy for clinical T1-2, N0, M0 NSCLC between 2010 and 2012 and met all study criteria. Among these 9,849 MIS patients, a VATS approach was used in 79% (n = 7,824) and a robotic approach was used in 21% (n = 2,025). Figure 1 shows the percentage of open, VATS, and robotic lobectomies performed per year of study. Use of MIS increased with each year of the study. Specifically, of the 10,004 lobectomies performed in 2010, 2,203 (22%) were VATS and 333 (3.3%) were robotic, whereas by 2012, of the 10,161 lobectomies performed, 2,934 (29%) were VATS and 1,055 (10.4%) were robotic. That translated to a 215% increase in robotic use over the 3-year study.

Fig 1.

Use of open (white) versus video-assisted thoracoscopic (blue) versus robotic (turquoise) lobectomy from 2010 to 2012.

The number of unique institutions utilizing a MIS approach to lobectomies for patients with stage 1 lung cancer increased over the 3-year study period. Specifically, of 1,220 unique hospitals that performed lobectomies in 2010, 93 hospitals (8%) performed VATS and 117 (9.6%) performed robotic lobectomy; whereas by 2012, of 1,686 unique hospitals that performed lobectomies, 537 (32%) performed VATS and 208 (12.3%) performed robotic lobectomy. Of 10,557 lobectomies performed at academic/research programs, 940 (9%) were performed by a robotic approach and 3,555 (34%) were performed using a VATS approach. Of 19,425 lobectomies performed at nonacademic community programs, 1,084 (5%) were performed using a robotic approach and 4,265 (22%) were performed by VATS approach.

Perioperative Outcomes for MIS Versus Open Approaches

Propensity-score matching was used to create two groups of 9,390 patients each who had undergone an open or MIS approach who were well-matched with regard to baseline characteristics (Table 1). Table 2 shows perioperative and pathologic data for the two matched groups. The MIS group did not differ significantly from the open group in 30-day mortality but had a higher 30-day readmission rate as well as a shorter length of hospital stay.

Table 1.

Propensity-Matched Analysis of Open Versus Minimally Invasive Surgery (Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic or Robotic) Lobectomy: Patient Baseline Characteristics

| Patient Baseline Characteristics |

Open (n = 9,390) |

MIS (n = 9,390) |

SD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 68 (60,74) | 68 (60,74) | 0.1 |

| Female | 5,385 (57.3) | 5,375 (57.2%) | 0.9 |

| Race | |||

| White | 8,336 (88.8) | 8,263 (88%) | 0.7 |

| Black | 739 (7.9) | 785 (8.4) | 0.1 |

| Other | 315 (3.4) | 342 (3.6) | 1.3 |

| Charlson comorbidity score | |||

| 0 | 4,747 (50.6) | 4,670 (49.7) | 2.6 |

| 1 | 3,426 (36.5) | 3,446 (36.7) | 1.2 |

| 2+ | 1,217 (13.0) | 1,274 (13.6) | 1.9 |

| Education above median | 6,014 (64) | 5,961 (63.5) | 0.1 |

| Income above median | 6,886 (73.3) | 6,769 (72.1) | 1.1 |

| Facility | |||

| Academic/research program | 4,201 (44.7) | 4,269 (45.5) | 0.8 |

| Community cancer program | 608 (6.5) | 397 (4.2) | 0.1 |

| Comprehensive community cancer program | 4,581 (48.8) | 4,724 (50.3) | 0.8 |

| Insurance | |||

| Private | 3,492 (37.6) | 3,575 (38.4) | 2.4 |

| Medicare/Medicaid | 5,583 (60.1) | 5,551 (59.6) | 1.8 |

| Uninsured | 212 (2.3) | 195 (2.1) | 2.1 |

| Clinical T status | |||

| T1 | 6,685 (71.2) | 6,598 (70.3) | 2.0 |

| T2 | 2,705 (28.8) | 2,792 (29.7) | 2.0 |

| Tumor location | |||

| Left lower lobe | 1,358 (14.5) | 1,404 (15) | 0.6 |

| Left upper lobe | 2,376 (25.3) | 2,301 (24.5) | 0.01 |

| Right lower lobe | 1,673 (17.8) | 1,714 (18.3) | 0.7 |

| Right middle lobe | 621 (6.6) | 639 (6.8) | 1.4 |

| Right upper lobe | 3,208 (34.2) | 3,179 (33.9) | 2.1 |

| Unknown | 154 (1.6) | 153 (1.6) | 0.4 |

| Induction therapy | 138 (1.5) | 120 (1.3) | 0.2 |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

IQR = interquartile range; MIS = minimally invasive surgery; SD = standardized difference.

Table 2.

Propensity-Matched Analysis of Open Versus Minimally Invasive Surgery (Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic or Robotic) Lobectomy: Perioperative and Postoperative Data

| Perioperative and Postoperative Data |

Open (n = 9,390) |

MIS (n = 9,390) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment specifics | |||

| Days to definitive surgery | 28 (4–49) | 28 (0–49) | 0.34 |

| Adjuvant therapy | |||

| Radiotherapy | 289 (3.1) | 273 (2.9) | 0.49 |

| Chemotherapy | 1,269 (13.7) | 1,257 (13.5) | 0.69 |

| Chemoradiation | 207 (2.2) | 180 (1.9) | 0.17 |

| Surgical endpoints | |||

| Nodes removed | 8 (5–12) | 8 (5–13) | <0.01 |

| Surgical margins | 0.36 | ||

| Negative | 9,143 (97.8) | 9,139 (97.6) | |

| Positive margin, microscopic | 127 (1.4) | 150 (1.6) | |

| Positive margin, macroscopic | 82 (0.9) | 77 (0.8) | |

| Short-term outcomes | |||

| Thirty-day mortality | 117 (1.8) | 79 (1.5) | 0.13 |

| Thirty-day readmission | 375 (4) | 467 (5) | 0.01 |

| Hospital length of stay, days | 6 (4,8) | 5 (3,7) | <0.01 |

| Tumor characteristics | |||

| Pathologic tumor size, cm | 2.7 ± 2.1 | 2.7 ± 2.1 | 0.65 |

| Pathologic T statusa | 0.04 | ||

| T0 (in situ) | 7 (0.1) | 12 (0.1) | |

| T1 | 5,398 (59.7) | 5,259 (57.8) | |

| T2 | 3,222 (35.6) | 3,386 (37.2) | |

| T3 | 362 (4.0) | 393 (4.3) | |

| T4 | 56 (0.6) | 44 (0.5) | |

| Pathologic N statusb | 0.53 | ||

| N0 | 7,861 (87.8) | 7,969 (88.5) | |

| N1 | 728 (8.1) | 691 (7.7) | |

| N2 | 366 (4.1) | 338 (3.8) | |

| N3 | 1 (0.0) | 3 (0.0) | |

| Pathologic M statusc | 0.47 | ||

| M0 | 9,300 (99.8) | 9,295 (99.7) | |

| M1 | 21 (0.2) | 26 (0.3) | |

| Graded | 0.64 | ||

| Well differentiated | 1,813 (20.5) | 1,826 (20.5) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 4,167 (47.2) | 4,255 (47.9) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 2,758 (31.2) | 2,722 (30.6) | |

| Undifferentiated/anaplastic | 97 (1.1) | 86 (1) |

Data missing for 641 patients.

Data missing for 823 patients.

Data missing for 138 patients.

Data missing for 1,056 patients.

Values are median (interquartile range), n (%), or mean ± SD.

MIS = minimally invasive surgery.

Although there was a statistically significant difference in the distribution of nodes removed between the groups that showed more lymph nodes removed with an MIS approach, this difference is likely not clinically significant, and a median 8 nodes were removed with both open and MIS approaches. The rates of nodal upstaging in this cN0 cohort to either pN1 or pN2 were not significantly different between the approaches.

Because survival data are not yet available in the NCDB for 2012 patients, short-term survival was evaluated using a propensity-matched analysis of open versus MIS patients from 2010 to 2011. There were 5,559 patients in each group. After matching, covariates were well-balanced between the groups with residual standardized differences of means for all confounders < 10% (data not shown). The open group statistically had a significantly worse overall survival when compared with the MIS group (p = 0.035) although the actual differences in 2-year survival between open lobectomy (86%; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 85% to 87%) versus MIS lobectomy (87%; 95% CI: 86% to 88%) were small.

Perioperative Outcomes for VATS Versus Robotic Lobectomy

Propensity-score matching was used to create two groups of 1,938 patients each who had undergone a VATS or robotic approach who were well matched with regard to baseline characteristics (Table 3). Table 4 shows perioperative and pathologic data for these two matched groups. Slightly more lymph nodes were removed with the VATS approach. The rates of nodal upstaging in this cN0 cohort to either pN1 or pN2 were not significantly different between the approaches. In propensity-matched analysis of VATS versus robotic patients from 2010 to 2011 that created two groups of 924 patients each, there were no significant differences between VATS versus robotic lobectomy in short-term overall survival (2-year overall survival VATS 86%, 95% CI: 84% to 88%, versus robotic 85.3%, 95% CI: 83% to 88%, p = 0.9).

Table 3.

Propensity-Matched Analysis of Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Versus Robotic Lobectomy: Patient Baseline Characteristics

| Patient Baseline Characteristics |

VATS (n = 1,938) |

Robotic (n = 1,938) |

SD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 69 (62–74) | 68 (61–74) | 1.1 |

| Female | 1,079 (55.7) | 1,099 (56.7) | 0.9 |

| Race | |||

| White | 1,721 (88.8) | 1,687 (87) | 3.4 |

| Black | 168 (8.7) | 184 (9.5) | 2.6 |

| Other | 49 (2.5) | 67 (3.5) | 2.0 |

| Charlson comorbidity score | |||

| 0 | 863 (44.5) | 889 (45.9) | 2.2 |

| 1 | 811 (41.8) | 762 (39.3) | 2.3 |

| 2+ | 264 (13.6) | 287 (14.8) | 0.3 |

| Education above median | 1,131 (58.4) | 1,093 (56.4) | 1.8 |

| Income above median | 1,334 (68.8) | 1,311 (67.6) | 1.0 |

| Facility | |||

| Academic/research program | 908 (46.9) | 887 (45.8) | 6.0 |

| Community cancer program | 86 (4.4) | 66 (3.4) | 0.9 |

| Comprehensive community cancer program | 944 (48.7) | 985 (50.8) | 5.1 |

| Insurance | |||

| Private | 691 (35.9) | 704 (36.7) | 4.2 |

| Medicare/Medicaid | 1,199 (62.3) | 1,161 (60.6) | 2.6 |

| Uninsured | 36 (1.9) | 51 (2.7) | 4.4 |

| Clinical T status | |||

| T1 | 1,445 (74.6) | 1,401 (72.3) | 7.3 |

| T2 | 493 (25.4) | 537 (27.7) | 7.3 |

| Tumor location | |||

| Left lower lobe | 309 (15.9) | 309 (15.9) | 0.4 |

| Left upper lobe | 475 (24.5) | 443 (22.9) | 0.5 |

| Right lower lobe | 377 (19.5) | 375 (19.3) | 0.9 |

| Right middle lobe | 109 (5.6) | 130 (6.7) | 3.1 |

| Right upper lobe | 641 (33.1) | 653 (33.7) | 3.3 |

| Unknown | 27 (1.4) | 28 (1.4) | 1.7 |

| Induction therapy | 14 (0.7) | 14 (0.7) | 0.6 |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

IQR = interquartile range; SD = standardized difference; VATS = video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Table 4.

Propensity-Matched Analysis of Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Versus Robotic Lobectomy: Perioperative and Postoperative Data

| Perioperative and Postoperative Data |

VATS (n = 1,938) |

Robotic (n = 1,938) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment specifics | |||

| Days to definitive surgery | 27 (0–48) | 31 (6–53) | <0.01 |

| Adjuvant therapy | |||

| Radiotherapy | 42 (2.2) | 60 (3.1) | 0.09 |

| Chemotherapy | 221 (11.6) | 251 (13.1) | 0.17 |

| Chemoradiation | 23 (1.2) | 38 (2) | 0.07 |

| Surgical endpoints | |||

| Conversion to open | 340 (17.5) | 200 (10.3) | <0.01 |

| Nodes removed | 9 (5–14) | 8 (5–13) | 0.01 |

| Surgical margins | 0.32 | ||

| Negative | 1,881 (97.6) | 1,888 (97.6) | |

| Positive margin-microscopic | 29 (1.5) | 35 (1.8) | |

| Positive margin-macroscopic | 18 (0.9) | 11 (0.6) | |

| Short-term outcomes | |||

| Thirty-day mortality | 17 (1.5) | 12 (1.3) | 0.96 |

| Thirty-day readmission | 103 (5.3) | 89 (4.6) | 0.34 |

| Hospital length of stay, days | 5 (3–7) | 5 (3–7) | 0.34 |

| Tumor characteristics | |||

| Pathologic tumor size, cm | 2.6 ± 1.4 | 2.7 ± 2.3 | 0.16 |

| Pathologic T statusa | 0.39 | ||

| T0 (in situ) | 5 (0.3) | 3 (0.2) | |

| T1 | 1,143 (61.0) | 1,112 (59.5) | |

| T2 | 625 (33.4) | 665 (35.6) | |

| T3 | 87 (4.6) | 82 (4.4) | |

| T4 | 13 (0.7) | 7 (0.4) | |

| Pathologic N statusb | 0.55 | ||

| N0 | 1,661 (89.4) | 1,652 (89.0) | |

| N1 | 138 (7.4) | 136 (7.3) | |

| N2 | 65 (3.5) | 67 (3.6) | |

| N3 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | |

| Pathologic M statusc | 1.00 | ||

| M0 | 1,910 (99.7) | 1,910 (99.7) | |

| M1 | 6 (0.3) | 6 (0.3) | |

| Graded | 0.19 | ||

| Well differentiated | 359 (19.6) | 415 (22.5) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 897 (48.9) | 865 (46.9) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 565 (30.8) | 551 (29.9) | |

| Undifferentiated/anaplastic | 13 (0.7) | 14 (0.8) |

Data missing for 134 patients.

Data missing for 155 patients.

Data missing for 44 patients.

Data missing for 107 patients.

Values are median (interquartile range), n (%), or mean ± SD.

VATS = video-assisted thoracoscopic.

There were no significant differences between the two groups with regard to 30-day mortality, 30-day readmission, and length of hospital stay. The number of days between diagnosis and surgery was longer by 4 days for the robotics group, but the conversion rate to open was significantly lower for the robotics group.

Comment

To our knowledge, this is the largest observational study to date comparing the outcomes between open versus MIS lobectomy and VATS versus robotic lobectomy for the treatment of stage I NSCLC. A VATS or robotic approach was used in 26% and 7% of all lobectomy cases, respectively, for stage I NSCLC from 2010 to 2012 in the NCDB. The percentage of MIS cases increased over the study period, and included a 215% increase in percentage of robotic lobectomies over 3 years. In propensity score matched analysis, the open group was found to have slightly decreased 30-day readmission rates and slightly longer hospital length of stay when compared with the MIS group, as well as slightly decreased 2-year survival. The MIS group did not have significantly different 30-day mortality from the open groups. In propensity score-matched analysis, the VATS group was found to have a higher conversion rate, slightly decreased days to definitive surgery, and slightly more nodes removed when compared with the robotic group. The VATS group did not differ significantly from the robotic group with regard to 30-day mortality and 2-year survival. With regard to nodal upstaging, there were no differences between open versus MIS and VATS versus robotic approaches in propensity score-matched analysis.

Our finding that VATS is used in approximately 26% of lobectomy cases is lower than previous analyses of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) general thoracic database, which found the VATS approach to be used in 49.1% of lobectomy cases [8]. The discrepancy may be explained in part by the differences the databases have with regard to types of reporting centers and surgeons. The NCDB presumably captures operations performed by both general surgeons and thoracic surgeons in both community and academic settings whereas more than 97% of reporting physicians in the STS general thoracic database are thoracic surgeons [9]. The STS database may also have a larger proportion of higher-volume thoracic surgeons than the NCDB.

The findings of our analysis of open versus MIS lobectomy for stage I NSCLC are generally consistent with previous studies that have noted improved survival in the MIS group with no difference in perioperative mortality between the two groups [1]. However, we found no significant difference in N0 to N1 or N0 to N2 nodal upstaging between open versus MIS groups in a propensity-matched analysis, which is in contrast to findings from two previous studies. A national study of the Danish Lung Cancer Registry found an increase in N0 to N1 and N0 to N2 upstaging associated with open lobectomy when compared with VATS lobectomy [10]. In addition, recent propensity-matched analyses of the STS database found no differences in N0 to N2 upstaging between VATS and open groups, but found that N0 to N1 upstaging was less common with VATS when compared with open procedures [11]. The difference between our study and the Danish and STS studies may be due to differences in staging between the studies. The American Joint Commission on Cancer sixth edition was used for the Danish study and was used for more than 50% of patients in the STS study. This resulted in the inclusion of a significant number of tumors in the Danish and STS studies that would have been classified as T2b using the 7th edition; T2b tumors are not included in the present study [3]. Another key difference between the current study and the STS and Danish studies is with respect to the study period. The Danish study included patients from 2007 to 2011 and the STS study included patients from2001 to 2010, whereas our study only evaluated patients from 2010 to 2012. It is possible that, with time and experience, lymph node evaluations may have improved.

Our finding that robotics is used in approximately 7% of lobectomy cases is higher than previous analyses of the State Inpatient Databases, which found robotics to be performed in 3.4% of lobectomy cases in 2010 [12]. The State Inpatient Databases contains primarily data from community hospital inpatient discharge records whereas the NCDB includes data from both community and academic centers [13]. We found a higher percentage of robotics being performed in academic centers than in community cancer programs, which likely explains the differences in percentages found between the present study and the State Inpatient Databases analysis.

Currently, there are few studies comparing outcomes between robotic versus open approaches and robotic versus VATS approaches [6, 12, 14–18]. Three small multicenter studies have suggested similar perioperative mortality rates and length of stay between the VATS and robotic approach [12, 14, 15], with one of these studies also showing reduced mortality, length of stay, and complications with the robotic lobectomy when compared with the open approach [12]. However, one study of the Nation-wide Inpatient Sample found that the robotic approach was associated with a higher rate of intraoperative injury and bleeding when compared with the VATS approach [6], although this study was limited by absence of staging data, and it is unclear how many patients underwent robotic lobectomy for stage I disease. One recent study of 302 robotic lobectomies also suggested that the robotic approach had improved nodal upstaging when compared with the VATS approach [3]. In contrast, our study found no differences in perioperative mortality, 2-year survival, and nodal upstaging between VATS versus robotic lobectomy. The much larger sample size and better staging data available in the present study may explain some of the discrepancies between our study findings and those of previous studies. Another consideration is that there may not be an inherent advantage intrinsic to any specific approach, and perhaps more important factors are how a particular surgeon harvests nodes and how extensively the specimen is pathologically examined.

This study has several limitations. First, the study is retrospective, and there is a possibility for unobserved confounding and selection bias. Second, although we propensity matched patient and tumor characteristics to reduce bias, there are important covariates such as surgeon experience and detailed comorbidity information that are not available in the NCDB. Third, detailed information regarding complications does not exist in the NCDB. Fourth, other long-term outcomes including 5-year overall survival and disease-free survival were not available because the NCDB only started recording information regarding surgical approach from 2010 onward.

In conclusion, MIS approaches are associated with shorter hospital stay and no apparent oncologic compromise in terms of nodal evaluation and upstaging or short-term survival when used to perform lobectomy for stage I NSCLC in a population-based analysis. However, MIS techniques are used in the minority of patients. Considering other benefits that have been demonstrated for MIS lobectomy, these results suggest that broader implementation of MIS techniques is needed for early stage lung cancer. Given that robotic and VATS approaches have similar short-term and oncologic outcomes, surgeons should consider either of these approaches as an alternative to thoracotomy in the context of their experience and availability of resources, as well as overall patient cost.

Acknowledgments

Dr Yang is supported by the American College of Surgeons Resident Research Scholarship. Drs Gulack and Hartwig are supported by the NIH-funded Cardiothoracic Surgery Trials Network, 5U01HL088953-05.

Footnotes

The data used in this study are derived from a deidentified National Cancer Data Base file. The American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer have not verified and are not responsible for the analytic or statistical methodology used or the conclusions drawn from these data by the investigators.

References

- 1.Yan TD, Black D, Bannon PG, McCaughan BC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized trials on safety and efficacy of video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2553–2562. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathisen DJ. Is video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy inferior to open lobectomy oncologically? Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:755–756. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson JL, Louie BE, Cerfolio RJ, et al. The prevalence of nodal upstaging during robotic lung resection in early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:1901–1907. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park BJ. Cost concerns for robotic thoracic surgery. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;1:56–58. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2012.04.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasir BS, Bryant AS, Minnich DJ, Wei B, Cerfolio RJ. Performing robotic lobectomy and segmentectomy: cost, profitability, and outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paul S, Jalbert J, Isaacs AJ, Altorki NK, Isom OW, Sedrakyan A. Comparative effectiveness of robotic-assisted versus thoracoscopic lobectomy. Chest. 2014;146:1505–1512. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-3032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. New York: Springer; 2010. American Joint Committee on Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burt BM, Kosinski AS, Shrager JB, Onaitis MW, Weigel T. Thoracoscopic lobectomy is associated with acceptable morbidity and mortality in patients with predicted postoperative forced expiratory volume in 1 second or diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide less than 40% of normal. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:19.e11–29.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shahian DM, Jacobs JP, Edwards FH, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons national database. Heart. 2013;99:1494–1501. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Licht PB, Jorgensen OD, Ladegaard L, Jakobsen E. A national study of nodal upstaging after thoracoscopic versus open lobectomy for clinical stage I lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:943–950. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boffa DJ, Kosinski AS, Paul S, Mitchell JD, Onaitis M. Lymph node evaluation by open or video-assisted approaches in 11,500 anatomic lung cancer resections. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kent M, Wang T, Whyte R, Curran T, Flores R, Gangadharan S. Open, video-assisted thoracic surgery, and robotic lobectomy: review of a national database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.07.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steiner C, Elixhauser A, Schnaier J. The healthcare cost and utilization project: an overview. Effect Clin Pract. 2002;5:143–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams RD, Bolton WD, Stephenson JE, Henry G, Robbins ET, Sommers E. Initial multicenter community robotic lobectomy experience: comparisons to a national database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:1893–1900. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swanson SJ, Miller DL, McKenna RJ, et al. Comparing robot-assisted thoracic surgical lobectomy with conventional video-assisted thoracic surgical lobectomy and wedge resection: results from a multihospital database (premier) J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:929–937. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee BE, Korst RJ, Kletsman E, Rutledge JR. Transitioning from video-assisted thoracic surgical lobectomy to robotics for lung cancer: are there outcomes advantages? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:724–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Augustin F, Bodner J, Maier H, et al. Robotic-assisted minimally invasive versus thoracoscopic lung lobectomy: comparison of perioperative results in a learning curve setting. Langenbeck’s Arch Surgery/Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Chirurgie. 2013;398:895–901. doi: 10.1007/s00423-013-1090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Louie BE, Farivar AS, Aye RW, Vallieres E. Early experience with robotic lung resection results in similar operative outcomes and morbidity when compared with matched video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:1598–1605. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]