Abstract

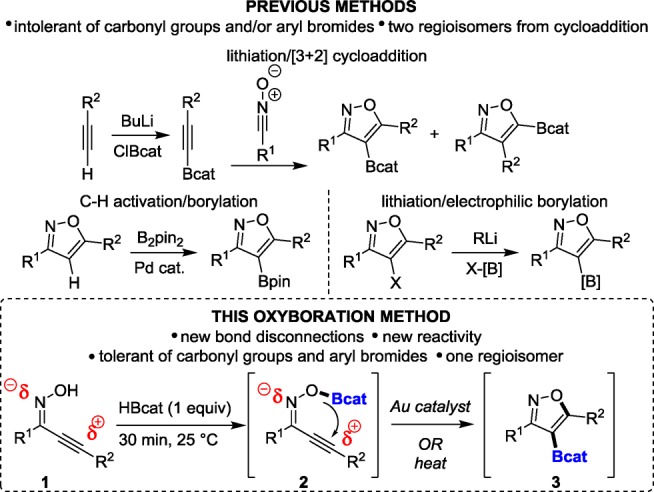

Herein we report an oxyboration reaction with activated substrates that employs B–O σ bond additions to C–C π bonds to form borylated isoxazoles, which are potential building blocks for drug discovery. Although this reaction can be effectively catalyzed by gold, it is the first example of uncatalyzed oxyboration of C–C π bonds by B–O σ bonds—and only the second example that is catalyzed. This oxyboration reaction is tolerant of groups incompatible with alternative lithiation/borylation and palladium-catalyzed C–H activation/borylation technologies for the synthesis of borylated isoxazoles.

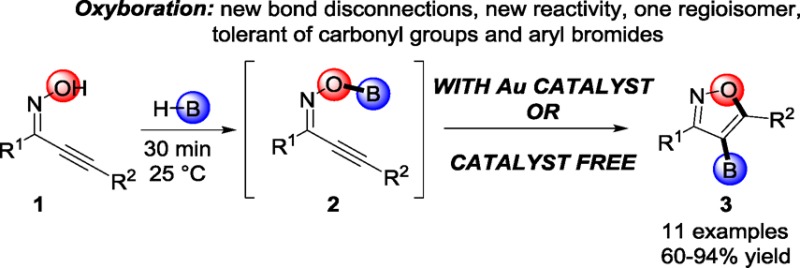

Isoxazoles1 exhibit a wide variety of biological activities, including analgesic,2 antibiotic,3 antidepressant,4 and anticancer5 activities. Consequently, borylated isoxazoles are valuable bench-stable building blocks for drug discovery.6 Oxyboration reactions that proceed through the addition of B–O σ bonds to C–C π bonds would be an attractive route to these and other building blocks by transforming easily formed B–O σ bonds into more difficult to form B–C σ bonds. Yet the addition of B–O σ bonds to C–C multiple bonds had remained elusive for 65 years7 until our first report in 2014.8a We herein report catalyzed and uncatalyzed oxyboration routes to borylated isoxazoles. This is the first report of an uncatalyzed oxyboration of C–C π bonds with B–O σ bonds. This oxyboration method is tolerant of a wide variety of functional groups and produces exclusively the 4-borylated regioisomer, which establishes the generality of oxyboration strategies8 to generate borylated heterocycles for drug discovery. Specifically, compounds of this type may currently be accessed through the [3 + 2] cycloaddition reaction of nitrile oxides and alkynylboronates as shown in Scheme 1. However, this method can produce two regioisomers, and the alkynylboronate synthesis involves a lithiation step.9 Alternatively, the Pd(0)-catalyzed Miyaura borylation10 and lithiation/electrophilic borylation11 have been used for the synthesis of borylated heterocycles, but as with lithiation/cycloaddition, aryl bromides and electrophilic functional groups are reactive under these conditions.

Scheme 1. Comparison of Previous Methods and New Oxyboration Method for the Synthesis of 4-Borylated Isoxazoles.

Inspired by previous reports from Perumal12 and Ueda,13 who demonstrated analogous Au-catalyzed rearrangements of oximes to form 4-substituted isoxazoles without boron, we considered that analogous routes to borylated isoxazoles may be assessable through oxyboration. We hypothesized that this gold-catalyzed oxyboration reaction could proceed through carbophilic Lewis acid activation of the C–C π bond, a mechanistically distinct route to B–Element addition reactions.8 The oxyboration reaction developed here is an operationally simple one-pot procedure from oximes and requires no isolation of reaction intermediates (Scheme 1).

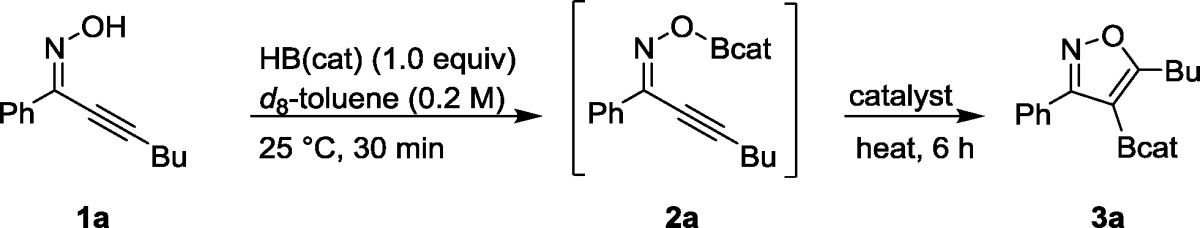

The reaction was developed through optimization studies with model substrate 1a. We first investigated a series of Au catalysts through varying the oxidation state and counterion (Table 1, entries 1–5). The catalyst IPrAuTFA proved an optimal balance of counterion coordinating ability.14 The catalyst IPrAuOAc, with the more strongly coordinating acetate ion,14b did not lead to any detectable product formation. A control reaction with catalytic NaTFA (entry 6) in place of IPrAuTFA showed no product, confirming a key role for the gold. Control experiments with IPrAuCl (no product formation) and separately with AgTFA (30% 1H NMR yield of product vs 90% under identical conditions but with IPrAuTFA) confirmed the catalytic activity was optimal with IPrAuTFA and not its synthetic precursors (entries 7–9). A survey of catalyst loading and reaction temperature (entries 10–13) determined the optimal loading to be 2.5 mol %, resulting in full conversion (90% 1H NMR yield) after 6 h at 50 °C.

Table 1. Selected Data from Optimization Studya.

| entry | catalyst | temp (°C) | cat. loading (% mol) | yieldb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AuCl | 50 | 2.5 | 0 |

| 2 | AuCl3 | 50 | 2.5 | 0 |

| 3 | IPrAuOAc | 50 | 2.5 | 0 |

| 4 | IPrAuOTs | 50 | 2.5 | 34 |

| 5 | IPrAuTFA | 50 | 2.5 | 90 |

| 6 | NaTFA | 50 | 2.5 | 0 |

| 7 | None | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | IPrAuCl | 50 | 2.5 | 0 |

| 9 | AgTFA | 50 | 2.5 | 48 |

| 10 | IPrAuTFA | 50 | 1.0 | 85c |

| 11 | IPrAuTFA | 50 | 5.0 | 90 |

| 12 | IPrAuTFA | 50 | 10 | 92 |

| 13 | IPrAuTFA | 25 | 10 | 89d |

Reactions were carried out on a 0.10 mmol scale.

Yields were determined by the ERECTIC method using mesitylene as 1H NMR external standard.

23 h.

22 h.

Interestingly, oxyboration of 1a could be carried out under catalyst-free conditions, albeit with higher temperatures and longer reaction times. Specifically, heating 1a to 110 °C for 17 h afforded 3a in 58% 1H NMR yield (Table 2). Similarly, cyclization of 1c under catalyst-free conditions of 110 °C for 17 h produced 3c in 89% 1H NMR yield. We hypothesize that the Michael-acceptor/polar character of the starting materials enables this catalyst-free oxyboration through lowering the barrier of cyclization (Scheme 1); alternatively, the nucleophilic nitrogen lone pair15 of the hydroxylimine may coordinate and activate the boron. Identification of this class of activated substrates thus provides access to catalyst-free reactivity that was not possible within our earlier reported oxyboration substrates.8 In contrast to the reactivity exhibited by 1a and 1c, when silylated 1f was used as the substrate for catalyst-free oxyboration, only B–O σ-bond formation was observed (boric ester 2f), and no cyclized products were formed even after an extended time of heating at 110 °C. This lack of reactivity possibly derives from the steric hindrance and the electron-donating ability of the trimethylsilyl group16 adjacent to the alkyne carbon, which may alter the polarization of the alkyne, rendering it less susceptible to nucleophilic attack. Because of its reduced temperatures, shorter reaction times, and action with the silylated substrate, the metal-catalyzed route was selected for further isolation.

Table 2. Initial Reaction Development with and without Catalyst.

| R1/R2 | IPrAuTFA 6 h, 50 °C | uncat. 6 h, 50 °C | uncat. 17 h, 110 °C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | Ph/Bu | 90% | <1% | 58% |

| 1c | 4-BrC6H4/n-Bu | 93% | 4% | 89% |

| 1f | Ph/TMS | 87% | <1% | <1% |

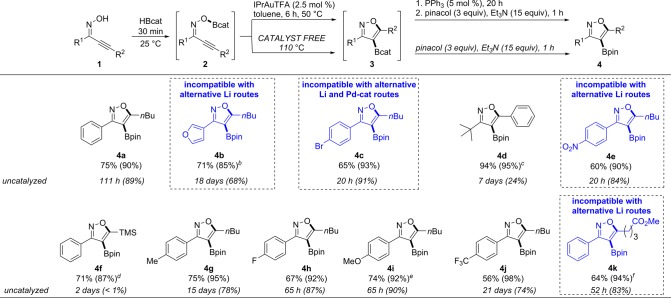

This oxyboration method provided a new set of bond disconnections to access previously unreported isoxazole pinacol boronic esters 4a–4k (except 4f(9)), which are isolable by silica gel chromatography and are bench-stable building blocks for a variety of downstream reactions6a,6b as shown in Scheme 2. The numbers in parentheses denote the 1H NMR spectroscopy yield of catechol boronic ester 3 relative to an external standard. The numbers outside the parentheses in the first row denote the isolated yield of bench-stable pinacol boronic ester 4.17 The numbers outside the parentheses in the second row correspond to the reaction time of the uncatalyzed oxyboration when run at 110 °C. After completion of the catalytic reaction, PPh3 was employed to quench the active catalyst IPrAuTFA by trapping it as the catalytically inactive [IPrAuPPh3]+.18

Scheme 2. Reaction Substrate Scope.

Substrates shown in blue are incompatible with alternative routes. All substrates give exclusively 4-borylated regioisomer. Isolated yield of 4 (1H NMR yield of 3). Uncatalyzed: Reaction time (1H NMR yield of 3).

50 °C, 24 h.

110 °C, 4 h.

90 °C 24 h.

60 °C 24 h

50 °C, 8h

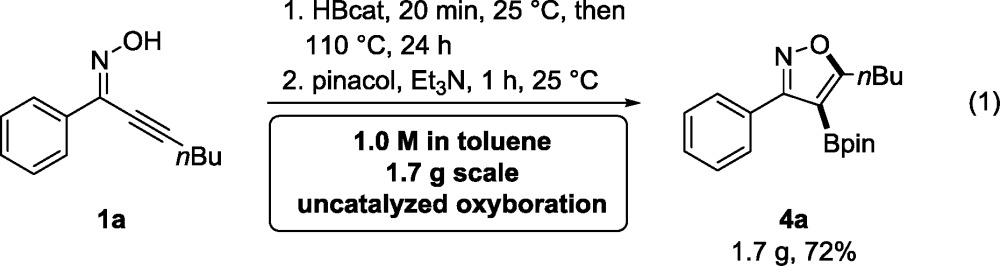

We herein compare the catalyzed reaction yields with those obtained through the uncatalyzed method for each substrate. To permit direct comparison, both reactions were performed at 0.2 M in substrate. The lengthy reaction times for the uncatalyzed reaction were reduced at higher concentration in substrate upon scale-up (eq 1). With the exception of silylated 1f, all substrates showed uncatalyzed reactivity at longer reaction times. Bulky substituents such as tert-butyl and trimethylsilyl, however, only produced very low 1H NMR yield (24% for 3d and <1% for 3f), with the starting materials remaining. Thus, they required catalysis for synthetically useful product formation. The electron-poor p-CF3 substrate and 3-furyl substrate required a rather lengthy 18–21 d to reach full conversion at 110 °C. In many cases, the cost benefit of obtaining the product under catalyst-free conditions may be desired in exchange for elevated temperatures and marginally longer reaction times, most notably with 4c, 4e, 4h, 4i, 4k, reactions which achieved similar 1H NMR yields to the catalyzed reactions in 20–65 h.

Interestingly, substrates that exhibited slow conversions under the catalyzed conditions for apparent electronic reasons (rather than steric reasons) such as 1i and 1k were the faster converting substrates under the uncatalyzed conditions; it may be that the electronics that favor π Lewis acid catalysis through gold–alkyne binding disfavor cyclization in the absence of a catalyst. This orthogonality in electronic and steric substrate reactivity highlights the complementarity provided by the catalyzed and uncatalyzed methods. Both the metal-catalyzed and the uncatalyzed oxyboration reactions are tolerant of functional groups that would otherwise be sensitive to alternative borylation methods. For example, aryl bromide 1c smoothly undergoes oxyboration to produce borylated isoxazole 3c (93% 1H NMR yield, 65% isolated yield of 4c with a catalyst; 91% 1H NMR yield without a catalyst). This substrate would be sensitive to a lithiation/borylation sequence11,19 because of competitive lithium/halogen exchange,20 and to an alternative palladium-catalyzed borylation10 because of competitive oxidative addition of the aryl–bromide bond. The nitro group in 1e and the ester group in 1k are similarly tolerated, producing oxyboration product 3e in 90% 1H NMR yield (60% isolated yield of 4e) and 3k in 94% 1H NMR yield (64% isolated yield of 4k) under catalysis whereas these groups are intolerant of alternative lithiation techniques.11 Furan-substituted 4b demonstrates the complementary bond disconnections enabled by oxyboration to avoid competitive ortho-borylation of the furan ring21 which would compete under alternative lithiation/borylation strategies (85% 1H NMR yield of 3b; 71% isolated yield of 4b).

In addition, heteroaryl (4b), aliphatic (4d), electron-poor aryl (4e, 4j, and 4k), silyl (4f), and electron-rich aryl (4g and 4i) are all compatible with the reaction conditions. Some substrates required a higher reaction temperature and/or longer reaction time to achieve full conversion under catalytic conditions, while no reaction was observed when the same conditions were applied in the absence of an Au catalyst. Oxyboration products 3d and 3f required 110 °C for 4 h and 90 °C for 24 h, respectively, which may be caused by the steric hindrance of the tert-butyl and the silyl groups. Electron-rich aryl 3i and heteroaryl 3b required heating at 60 °C for 24 h and 50 °C for 24 h, respectively, which may be attributed to the electron-donating ability of these substituents to reduce the electrophilicity of boron.

We proposed that a plausible catalytic cycle for the gold catalyzed oxyboration reaction could be similar to our previously published proposed mechanism for alkoxyboration,8a which highlights the activation of the C–C π bond by the carbophilic Lewis acid catalyst.22 Investigation of the proposed mechanism for both the catalyzed and uncatalyzed oxyboration reactions are currently underway in our laboratory.

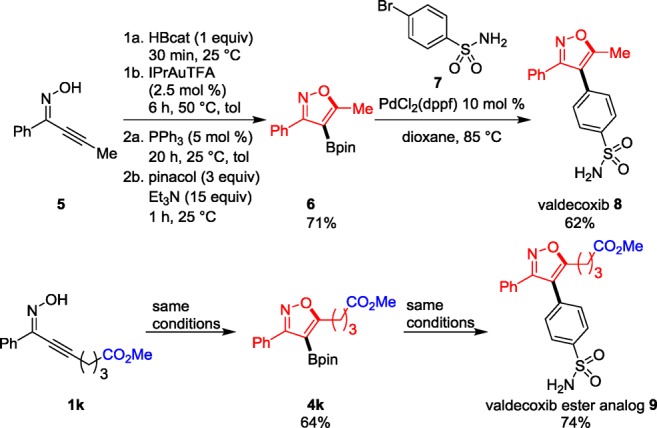

Synthetic Utility. The utility of the oxyboration reaction to generate building blocks for pharmaceutical targets was showcased through the synthesis of valdecoxib, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID),23 and its analog. Our synthetic route is shown in Scheme 3. Under standard catalytic conditions, bench-stable pinacol boronate building blocks 6 and 4k were generated from oximes 5 and 1k in 71% and 64% isolated yields, respectively. Suzuki cross-coupling of these borylated isoxazoles with p-bromobenzenesulfonamide 7 afforded valdecoxib 8 and valdecoxib ester analog 9 in 62% and 74% isolated yields, respectively. This synthesis provides the key substituted organoboron building block 6 in higher isolated yield, compared to the competing route with [3 + 2] cycloaddition of nitrile oxides and alkylboronates, which formed the same organoboron 6 in only 54% isolated yield in a route employed in a previously reported synthesis of valdecoxib.9

Scheme 3. Oxyboration Synthesis of Valdecoxib.

Additionally, the application of oxyboration to the synthesis of ester-containing valdecoxib analog 9 showcases the utility of the functional group tolerance of this oxyboration method. Previously reported syntheses of valdecoxib from academic9,11 and industrial23 laboratories involve lithiation steps that are not compatible with ester functional groups. These applications demonstrate the versatility and efficiency of the oxyboration reaction for the construction of pharmaceutical targets.

Access to a cost-effective uncatalyzed version of the reaction is particularly desirable on scale, wherein the cost of the catalyst may become a significant consideration that outweighs time considerations. The uncatalyzed oxyboration reaction scales well. Compound 1a was successfully converted to 1.7 g of pinacol boronate 4a on a 7.3 mmol scale under catalyst-free conditions in 24 h with 1.0 M in 1a (eq 1, vide supra). The reaction time was reduced significantly when the starting material concentration was increased to the widely employed concentration in the chemical industry. This convenient scalability demonstrates that quantities of these heterocyclic boronic acid building blocks that are sufficient for multistep downstream synthesis may be prepared by this oxyboration method.

|

1 |

In conclusion, we have developed a method for preparing 4-borylated isoxazoles via oxyboration. This reaction proceeds with catalytic gold(I), or for many substrates without an added catalyst in the first reported uncatalyzed oxyboration reaction of C–C multiple bonds with B–O σ bonds. The reaction conditions are sufficiently mild to form functionalized borylated isoxazoles in good yields and in exclusively one regioisomer. The utility and functional group compatibility of this method were highlighted in the synthesis of valdecoxib and a valdecoxib ester analog and an effective scale-up reaction.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH (1R01GM098512-01) and the University of California, Irvine, for funding. We thank Dr. Eugene Chong (The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI), Mr. Drew W. Cunningham, and Mr. Darius J. Faizi (The University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA) for helpful conversations. We thank Dr. John Greaves, Mr. Beniam Berhane, and Ms. Shirin Sorooshian (The University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA) for mass spectrometry analysis.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03530.

Full experimental procedures, characterization data and 1H and 13NMR spectra (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Provisional patent application (no. 62/198,410) has been filed by the University of California..

Supplementary Material

References

- Pinho e Melo T. M. V. D. Curr. Org. Chem. 2005, 9, 925–958. 10.2174/1385272054368420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daidone G.; Raffa D.; Maggio B.; Plescia F.; Cutuli V. M. C.; Mangano N. G.; Caruso A. Arch. Pharm. 1999, 332, 50–54. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cali P.; Nærum L.; Mukhija S.; Hjelmencrantz A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 5997–6000. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.09.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Yu L.-F.; Eaton J. B.; Caldarone B.; Cavino K.; Ruiz C.; Terry M.; Fedolak A.; Wang D.; Ghavami A.; Lowe D. A.; Brunner D.; Lukas R. J.; Kozikowski A. P. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 7280–7288. 10.1021/jm200855b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumbhare R. M.; Kosurkar U. B.; Janaki Ramaiah M.; Dadmal T. L.; Pushpavalli S. N.; Pal-Bhadra M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 5424–5427. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Burke M. D.; Berger E. M.; Schreiber S. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 14095–14104. 10.1021/ja0457415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mlynarski S. N.; Karns A. S.; Morken J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 16449–16451. 10.1021/ja305448w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Gutiérrez M.; Matus M. F.; Poblete T.; Amigo J.; Vallejos G.; Astudillo L. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2013, 65, 1796–1804. 10.1111/jphp.12180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Vitale P.; Tacconelli S.; Perrone M. G.; Malerba P.; Simone L.; Scilimati A.; Lavecchia A.; Dovizio M.; Marcantoni E.; Bruno A.; Patrignani P. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 4277–4299. 10.1021/jm301905a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Tzanetou E.; Liekens S.; Kasiotis K. M.; Melagraki G.; Afantitis A.; Fokialakis N.; Haroutounian S. A. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 81, 139–149. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Cragg R. H.; Lappert M. F.; Tilley B. P. J. Chem. Soc. 1964, 2108–2115. 10.1039/jr9640002108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Matsumi N.; Chujo Y. Macromolecules 1998, 31, 3802–3806. 10.1021/ma971263p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Hirner J. J.; Faizi D. J.; Blum S. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 4740–4745. 10.1021/ja500463p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chong E.; Blum S. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 10144–10147. 10.1021/jacs.5b06678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hirner J. J.; Blum S. A. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 4445–4449. 10.1016/j.tet.2015.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore J. E.; Davies M. W.; Goodenough K. M.; Wybrow R. A. J.; York M.; Johnson C. N.; Harrity J. P. A. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 6707–6714. 10.1016/j.tet.2005.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W.; Keshipeddy S.; Zhang Y.; Wei X.; Savoie J.; Patel N. D.; Yee N. K.; Senanayake C. H. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 1366–1369. 10.1021/ol2000556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velcicky J.; Soicke A.; Steiner R.; Schmalz H.-G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 6948–6951. 10.1021/ja201743j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Praveen C.; Kalyanasundaram A.; Perumal P. T. Synlett 2010, 2010, 777–781. 10.1055/s-0029-1219342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Kung K. K–Y.; Lo V. K–Y.; Ko H–M.; Li G–L.; Chan P–Y.; Leung K–C.; Zhou Z.; Wang M–Z.; Che C–M.; Wong M–K. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013, 355, 2055–2070. 10.1002/adsc.201300005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ueda M.; Sato A.; Ikeda Y.; Miyoshi T.; Naito T.; Miyata O. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 2594–2597. 10.1021/ol100803e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jeong Y.; Kim B.-I.; Lee J. K.; Ryu J.-S. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 6444–6455. 10.1021/jo5008702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ciancaleoni G.; Belpassi L.; Zuccaccia D.; Tarantelli F.; Belanzoni P. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 803–814. 10.1021/cs501681f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Jia M.; Bandini M. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 1638–1652. 10.1021/cs501902v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fina N. J.; Edwards J. O. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 1973, 5, 1–26. 10.1002/kin.550050102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gassman P. G.; Deck P. A.; Winter C. H.; Dobbs D. A.; Cao D. H. Organometallics 1992, 11, 959–960. 10.1021/om00038a069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Del Grosso A.; Singleton P. J.; Muryn C. A.; Ingleson M. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 2102–2106. 10.1002/anie.201006196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y.; Roth K. E.; Ramgren S. D.; Blum S. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 18022–18023. 10.1021/ja9068497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott H. K.; Aggarwal V. K. Chem. - Eur. J. 2011, 17, 13124–13132. 10.1002/chem.201102581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey W. F.; Patricia J. J. J. Organomet. Chem. 1988, 352, 1–46. 10.1016/0022-328X(88)83017-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung K.-S. Top. Heterocycl. Chem. 2012, 29, 47–76. 10.1007/7081_2012_79. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Gimeno A.; Cuenca A. B.; Suarez-Pantiga S.; de Arellano C.; Medio-Simon M.; Asensio G. Chem. - Eur. J. 2014, 20, 683–688. 10.1002/chem.201304087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tang Y.; Li J.; Zhu Y.; Li Y.; Yu B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 18396–18405. 10.1021/ja4064316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley J. J.; Brown D. L.; Carter J. S.; Graneto M. J.; Koboldt C. M.; Masferrer J. L.; Perkins W. E.; Rogers R. S.; Shaffer A. F.; Zhang Y. Y.; Zweifel B. S.; Seibert K. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 775–777. 10.1021/jm990577v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.