Abstract

Background

Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) occur in 70-90% of patients at different stages of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), but the available methods for managing these problems are of limited effectiveness.

Aim

Assess the effects of high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), applied over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), on BPSD and cognitive function in persons with AD.

Methods

Fifty-four patients with AD and accompanying BPSD were randomly divided into an intervention group (n=27) and a control group (n=27). In addition to standard antipsychotic treatment, the intervention group was treated with 20Hz rTMS five days a week for four weeks, while the control group was treated with sham rTMS.The Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease Rating Scale (BEHAVE-AD), the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive (ADAS-Cog), and the Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale (TESS) were administered by raters who were blind to the group assignment of patients before and after four weeks of treatment.

Results

Twenty-six subjects from each group completed the study. After four weeks of antipsychotic treatment with adjunctive real or sham rTMS treatment, the mean (sd) total BEHAVE-AD scores and mean total ADAS-Cog scores of both groups significantly decreased from baseline. After adjusting for baseline values, the intervention group had significantly lower scores (i.e., greater improvement) than the control group on the BEHAVE-AD total score, on five of the seven BEHAVE-AD factor scores (activity disturbances, diurnal rhythm, aggressiveness, affective disturbances, anxieties and phobias), on the ADAS-Cog total score, and on all four ADAS-Cog factor scores (memory, language, constructional praxis, and attention). The proportion of individuals whose behavioral symptoms met a predetermined level of improvement (i.e., a drop in BEHAVE-AD total score of > 30% from baseline) in the intervention group was greater than that in the control group (73.1% vs.42.3%, X2=5.04, p=0.025).

Conclusion

Compared to treatment of AD with low-dose antipsychotic medications alone, the combination of low-dose antipsychotic medication with adjunctive treatment with high frequency rTMS can significantly improve both cognitive functioning and the behavioral and psychological symptoms that often accompany AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, behavioral and psychological symptoms, cognitive function, transcranial magnetic stimulation, China

Abstract

背景

:70-90%的阿尔茨海默氏病(Alzheimer's Disease, AD)患者在不同阶段都伴有痴呆的精神与行为症状(behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, BPSD), 但现有的针对这些问题的方法疗效十分有限。

目的

评估对AD患者的左背外侧前额叶皮层(left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, DLPFC)进行高频重复经颅磁刺激(repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, rTMS)对其BPSD和认知功能的疗效。

方法

将54例伴有BPSD的AD患者随机分为干预组(n=27)和对照组(n=27)。在常规抗精神病药物治疗的基础上, 干预组采用20 Hz的rTMS治疗, 每周五天, 共四周;而对照组采用伪磁刺激治疗。评估者采用阿尔茨海默病行为病理学评定量表(Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease Rating Scale, BEHAVE-AD)、阿尔茨海默氏病评估量表-认知分量表(Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive, ADAS-Cog)和副反应量表(Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale, TESS)对患者分别在4周治疗期前后进行盲法评估。

结果

每组都有26例患者完成了研究。抗精神病药治疗辅以磁刺激或伪磁刺激治疗4周后, 两组BEHAVEAD总分的均值(标准差)和ADAS-Cog总分的均值与基线相比均显著降低。校正基线值后, 干预组的BEHAVE-AD总分、BEHAVE-AD的7个因子分中5个(活动障碍、昼夜节律、攻击性、情感障碍、焦虑和恐惧)、ADAS总分以及ADAS量表4个因子分(记忆、语言、结构性练习、注意力)均显著低于对照组(即改善更明显)。事先将BEHAVE-AD总分比基线下降大于等于30%定义为症状改善, 干预组中行为症状改善的患者比例显著高于对照组(73.1% vs.42.3%, X2=5.04, p=0.025)。

结论

相较于单纯低剂量抗精神病药物治疗, 高频rTMS辅助低剂量抗精神病药物治疗能显著改善AD患者的认知功能和精神行为症状。

中文全文

本文全文中文版从2016年2月26日起在http://dx.doi.org/10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.215107可供免费阅览下载

1. Introduction

In China the prevalence of senile dementia in persons 60 years of age and older is reported to be 4.8%.[1] Dramatic improvements in health in China and the one child per family policy have resulted in a rapid increase in the proportion of the population that is elderly, and, thus, a similarly dramatic increase in the number of individuals with dementia. As the most common type of senile dementia, Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) has become a serious public health problem. AD is a primary degenerative cerebral disease of unknown etiology with a predominant clinical picture of cognitive impairment and different degrees of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). The incidence of BPSD during different stages of AD is 70-90%, [2, 3] and primarily consists of hallucinations, delusions, agitation, and behavioral disorders. Moreover, BPSD can exacerbate the cognitive and social dysfunction of AD, leading to decreased quality of life for both patients and caregivers, more frequent hospitalizations, and a higher burden of illness.

Currently, the management of BPSD usually involves the use of atypical antipsychotic medications at 1/3-1/2 the dosage recommended for primary psychosis.[4, 5] However, over the last decade several studies have reported increased rates of severe adverse reactions in AD patients treated with antipsychotic medications, primarily cardiovascular events and respiratory infections.[6] This has resulted in the increased use of other, non-pharmacological methods for managing BPSD, such as physical therapy.[7] Another alternative approach to BPSD might be the use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), a painless, non-invasive treatment that has been shown to be safe and effective for various neurological and psychiatric conditions.[8, 9] rTMS has a beneficial effect in the treatment of different mental disorders associated with the persistence of auditory hallucinations, agitation, anxiety, and depression; and it is associated with improved cognitive functioning.[10, 11, 12] Recent studies have shown that rTMS can delay the progression and improve cognitive function in AD without inducing any serious adverse events.[13, 14, 15, 16] But there have been few studies that assess the effects of rTMS on BPSD in persons with AD. The purpose of this study is to assess whether or not rTMS used as an adjunctive treatment to low-dose risperidone can improve the BPSD symptoms and cognitive functioning of individuals with AD.

2. Participants and methods

2.1. Participants

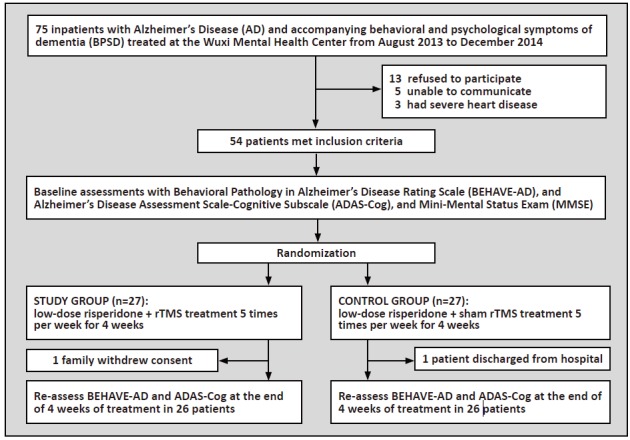

The recruitment and research procedures are shown in Figure 1. Participants in this study were recruited from the Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment Center at The Wuxi Mental Health Center from August 2013 to December 2014. Inclusion criteria were as foIlows: a) met the criteria for probable AD proposed by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disease and Stroke and Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA);[17] b) 60-80 years of age; c) minimum of 5 years of education; d) total score on Mini-Mental State Examination(MMSE)[18] of less than 24; e) total score on Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale (BEHAVE-AD)[19] of greater than 8; e) no history of epilepsy, stroke, or major head trauma; f) no severe physical illness or implants which could limit the use of rTMS; and g) had not taken antipsychotic medications or other drugs affecting mental activity in the previous month.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study

Fifty-four patients who met these inclusion criteria were randomly assigned (using a standard table of random numbers) before the commencement of the trial to either the intervention group or the control group. As shown in Table 1, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups at baseline in age, gender distribution, educational level, course of the disease, or MMSE score.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants

| characteristic | intervention group (n=26) |

control group (n=26) |

statistic | p-value |

| mean (sd) age in years | 71.4(4.9) | 71.9(4.8) | t=0.43 | 0.670 |

| gender (female/male) | 16/10 | 15/11 | X2=4.36 | 0.113 |

| mean (sd) years duration of illness | 5.1(1.5) | 5.1(1.5) | t=0.16 | 0.877 |

| mean (sd) years of education | 11.4(2.7) | 11.5(2.1) | t=0.23 | 0.821 |

| mean (sd) baseline total MMSEa | 15.3(3.1) | 15.2(3.1) | t=0.14 | 0.893 |

| aMMSE, Mini-Mental Status Exam | ||||

The protocol for this project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Wuxi Mental Health Center. Informed consents were obtained from all participants.

2.2. Intervention

This was a double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled study in which the rTMS therapist (who was not involved in the clinical assessment of the patients) used a random number table to assign subjects to either the real rTMS or the sham rTMS condition. In addition to conventional treatment with risperidone 1 mg per day, all patients were administered real or sham rTMS treatments for a total of 20 sessions, 5 days a week for 4 consecutive weeks. Other antipsychotic drugs were not used during the treatment.

A MagproR30 rTMS machine (with the figure-eight electromagnet) manufactured by Medtronic (a Danish company) was employed in the study. Patients lay down on a treatment table during the rTMS procedure. The stimulation position was over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC).[11] The stimulus intensity was 80% of the motor threshold (MT) and the frequency was 20 Hz for all patients. The total number of pulses was 1200 for a single treatment session. In the control group, the coils were turned 180 degrees so the magnetic field penetrating the brain was so weak that it was considered a sham condition; other settings were the same as those used in the intervention group.

2.3. Assessments

The primary outcome measure was the change in scores of the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale (BEHAVE-AD).[19] A secondary outcome was the change in scores of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADASCog).[20] BEHAVE-AD scores and ADAS-Cog scores were rated at baseline and after 4 weeks of treatment. The ratings were conducted by two attending-physician level psychiatrists who had been trained in the use of the scales and who were blind to the treatment status of the patients; their inter-rater reliability based on the simultaneous assessment of six patients was good (ICC=0.79-0.86). The percent reduction from baseline in the BEHAVE-AD total score was used to assess the effectiveness of treatment: based on cutoff scores used in a previous study,[21] those with ≥60% reduction were classified as ‘effectively treated’; those with 30-59% reduction were classified as ‘improved’; and those with < 30% reduction were classified as ‘not improved’.

BEHAVE-AD is a 25-item scale that assesses seven aspects of behavioral pathology including delusions and paranoid ideation, hallucinations, activity disturbances, aggressiveness, diurnal rhythm disturbances, affective disturbances, and anxieties and phobias; the range in scores is from 0 to 75, with lower scores representing better functioning. ADAS-Cog is a 12-item scale that assesses four aspects of cognitive functioning including memory, language, constructional praxis, and attention; the range in the total score is from 0 to 75, with lower scores representing better functioning.

Vital signs and adverse events were recorded at the time of each rTMS treatment. Routine blood tests, urine tests, electrocardiogram, blood biochemistry (liver and kidney function, electrolytes, glucose, etc.) tests and the Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale (TESS) were conducted at baseline and at the end of 4 weeks of treatment.

2.4. Statistical analysis

SPSS software version 13.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for analysis. Means (sd) were used to describe test scores. Mann-Whitney tests were used for variables with non-normal distributions. Chi-squared tests were used to compare categorical variables including gender and the proportion of patients in each group whose treatment was classified as ‘effective’. For normally distributed continuous measures, paired t-tests were performed to compare the BEHAVE-AD total score and each subscale score (except hallucinations), ADAS-Cog total score and each subscale score at baseline and after 4 weeks of treatment in each group. Two-sample t-tests were performed for between group comparisons. A repeated measures analysis of variance was also conducted to compare the change in the scale scores with treatment between the two groups after adjusting for the baseline values. The correlation between changes in BEHAVE-AD and ADAS-Cog was analyzed by Spearman correlation coefficients. The significant level was set at 0.05.

3. Results

As shown in Figure 1, one patient dropped out of each group, so the final analysis was based on data from the 26 subjects in each group that completed the 4-week treatment.

As shown in Table 2, there were no significant differences at baseline between groups in the total BEHAVE-AD score or in any of the seven BEHAVE-AD subscale scores. After 4 weeks of treatment, the total BEHAVE-AD score decreased (i.e., improved) significantly in both groups, but the decrease in the subscale scores was statistically significant for only six of the subscale scores in the intervention group and for only four of the subscale scores in the control group. The hallucination subscale score did not decrease significantly in either group. After controlling for baseline values using a repeated measures ANOVA, the improvement in the total BEHAVE-AD score after 4 weeks of treatment was significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group. The improvement was also greater in the intervention group for five of the seven BEHAVE-AD subscale scores: activity disturbances, diurnal rhythm disturbances, aggressiveness, affective disturbances, and anxiety and fear.

Table 2. Comparison of mean (sd) total and subscale scores on the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease Rating Scale (BEHAVE-AD) before and after 4 weeks of treatment in the study and control groups

| scale/subscale | time | intervention group (n=26) |

control group (n=26) |

t-value F-valuea |

p-value |

| total score | baseline | 14.00 (5.69) | 14.12 (5.08) | 0.08 | 0.939 |

| after treatment | 9.08 (4.27) | 11.96 (4.18) | 26.34 | < 0.001 | |

| paired t-test (p-value) | 12.82 (<0.001) | 5.68 (<0.001) | |||

| delusions and paranoid | baseline | 3.69 (1.46) | 3.73 (1.48) | 0.09 | 0.925 |

| ideations subscale score | after treatment | 3.08 (1.23) | 3.12 (1.21) | 0.00 | 1.000 |

| paired t-test (p-value) | 6.33 (<0.001) | 4.92 (<0.001) | |||

| hallucinations | baseline | 0.23 (0.59) | 0.27 (0.67) | 0.22 | 0.826 |

| subscale score | after treatment | 0.12 (0.33) | 0.17 (0.42) | 0.05 | 0.821 |

| paired t-test (p-value) | 1.81 (0.083) | 1.73 (0.096) | |||

| activity disturbances | baseline | 3.92 (1.74) | 4.19 (1.55) | 0.59 | 0.559 |

| subscale score | after treatment | 2.19 (1.90) | 3.46 (1.56) | 12.94 | 0.001 |

| paired t-test (p-value) | 12.18 (<0.001) | 3.06 (0.005) | |||

| aggressiveness | baseline | 2.38 (2.00) | 2.23 (1.80) | 0.29 | 0.772 |

| subscale score | after treatment | 1.50 (1.48) | 1.88 (1.53) | 5.79 | 0.020 |

| paired t-test (p-value) | 4.54 (<0.001) | 3.14 (0.004) | |||

| diurnal rhythm disturbances | baseline | 1.50 (0.51) | 1.46 (0.51) | 0.27 | 0.786 |

| subscale score | after treatment | 0.88 (0.65) | 1.31 (0.62) | 14.52 | < 0.001 |

| paired t-test (p-value) | 6.33 (<0.001) | 2.13 (0.043) | |||

| affective disturbances | baseline | 1.12 (0.71) | 1.15 (0.73) | 0.19 | 0.848 |

| subscale score | after treatment | 0.69 (0.47) | 1.12 (0.71) | 8.50 | 0.005 |

| paired t-test (p-value) | 4.28 (<0.001) | 0.44 (0.664) | |||

| anxiety and fear | baseline | 1.15 (0.67) | 1.08 (0.63) | 0.43 | 0.672 |

| subscale score | after treatment | 0.62 (0.50) | 0.92 (0.56) | 5.39 | 0.024 |

| paired t-test (p-value) | 4.24 (<0.001) | 1.44 (0.161) | |||

| aF-value is from the repeated measures ANOVA, adjusting for the baseline values of each variable | |||||

Based on considering a 60% decrease from baseline in the total BEHAVE-AD score as the cutoff for ‘effective treatment’, 30-59% for ‘improvement’, and < 30% for ‘no improvement’, 3 patients in the intervention group (11.5%) were effectively treated, 16 (61.5%) were improved, and 7 (26.9%) were not improved after treatment; in the control group 1 (3.8%) patient was effectively treated, 10 (38.5%) were improved, and 15 (41.7%) were not improved. That is, 73.1% (19/26) of the patients in the rTMS group showed improvement in their behavioral and psychological symptoms compared to only 42.3% (11/26) in the control group (X2=5.04, p=0.025).

As shown in Table 3, there were no significant differences in the ADAS-Cog total scores or in any of the four subscale scores between groups at baseline. After 4 weeks of treatment, the ADAS-Cog total scores dropped (i.e., improved) significantly in both groups, and the subscale scores dropped significantly in all four subscales in the intervention group and in two of the four subscales scores in the control group (the memory and attention subscales). After controlling for baseline values using a repeated measures ANOVA, the improvement in the total ADAS-Cog score after 4 weeks of treatment was significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group. The improvement was also greater in the intervention group for all four ADAS-Cog subscale scores: memory, language, constructional praxis, and attention.

Table 3. Comparison of mean (sd) total and subscale scores on the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive (ADAS-Cog) before and after 4 weeks of treatment in the study and control groups

| scale/subscale | time | intervention group (n=26) |

control group (n=26) |

t-value F-valuea |

p-value |

| total score | baseline | 30.08 (6.07) | 29.32 (6.31) | 0.44 | 0.659 |

| after treatment | 24.16 (5.21) | 27.65 (5.24) | 30.06 | <0.001 | |

| paired t-test (p-value) | 13.10 (<0.001) | 2.64 (0.014) | |||

| memory subscale score | baseline | 14.39 (4.94) | 14.28 (4.69) | 0.08 | 0.936 |

| after treatment | 10.70 (3.85) | 12.89 (4.04) | 13.06 | 0.001 | |

| paired t-test (p-value) | 12.45 (<0.001) | 2.45 (0.022) | |||

| language subscale score | baseline | 8.71 (3.27) | 8.78 (3.13) | 0.08 | 0.938 |

| after treatment | 7.98 (3.19) | 8.74 (3.25) | 6.12 | 0.017 | |

| paired t-test (p-value) | 7.74 (<0.001) | 0.12 (0.909) | |||

| constructional praxis | baseline | 3.41 (1.68) | 3.45 (1.66) | 0.08 | 0.941 |

| subscale score | after treatment | 3.22 (1.61) | 3.43 (1.64) | 24.15 | <0.001 |

| paired t-test (p-value) | 5.78 (<0.001) | 1.18 (0.250) | |||

| attention subscale score | baseline | 3.57 (1.70) | 2.81 (1.17) | 1.88 | 0.068 |

| after treatment | 2.27 (1.04) | 2.57 (1.09) | 7.62 | 0.008 | |

| paired t-test (p-value) | 3.48 (0.002) | 2.29 (0.031) | |||

| aF-value is from the repeated measures ANOVA, adjusting for the baseline values of each variable | |||||

Combining results for all 52 participants who completed the study, the correlation of the BEHAVEAD total score and the ADAS-Cog total score was nonsignificant, both at baseline (rs=0.11, p=0.459) and after treatment (rs=0.02, p=0.869). However, the magnitude of the change in the total scores of the two scales over the course of treatment was statistically significant (rs= 0.33, p=0.015).

During rTMS treatments, no patients experienced seizures or epilepsy-like symptoms. There were no changes in the ECG, EEG, or blood chemistry results. The most common adverse reactions in both groups reported on the TESS were mild extrapyramidal reactions (4 cases in the intervention group and 2 cases in the control group) and transient headache (4 cases in the intervention group and 5 cases in the control group). These side effects were mild and well tolerated. Overall, 30.8% (8/26) of the participants in the intervention group experienced an adverse event during the study while 26.9% (7/26) in the control group experienced an adverse event (X2=0.09, p=0.760).

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

This study used a randomized, double-blind design to compare the efficacy and safety of high frequency rTMS combined with low-dose risperidone to that of risperidone treatment alone for the treatment of BPSD in patients with AD. We found that 4 weeks of high frequency rTMS to the left DLPFC is an effective adjunctive treatment method for the treatment of BPSD in patients with AD. A much higher proportion of patients receiving rTMS than patients receiving sham rTMS experienced a 30% or greater drop in the overall BEHAVE-AD score (73.1% vs. 42.3%), indicating that the behavioral and psychological symptoms had substantially improved.

These findings are similar to those of other studies. Peng and colleagues[22] reported that TMS is more effective than drug therapy for BPSD, including sleep quality, anxiety and depression, aggression, and agitation. Another study in China by Wu and colleagues[23] also reported that rTMS improved BPSD, but the study did not include a sham rTMS comparison group. The efficacy of risperidone treatment alone reported in this study was similar to that reported by Onor and colleagues, [24] which found that low-dose risperidone was associated with reductions in agitation, aggression, irritability, delusions, and sleep disorders.

We found no significant improvement in either group in the hallucination subscale score of the BEHAVE-AD after 4 weeks of treatment. Becker and colleagues[25] regarded the occurrence of hallucinations as a marker of the severity of AD psychopathology; if true, this could explain the apparent insensitivity of hallucinations to treatment. On the other hand, a recent study[26] that reported the effectiveness of rTMS as an adjunctive treatment for auditory hallucinations used low-frequency stimulation, while our study used high-frequency rTMS. Future studies should assess the effectiveness of treating AD with low-frequency rTMS.

We also found that the cognitive functioning of the high frequency rTMS group improved significantly more than in the sham rTMS group that only received the low-dose risperidone. This finding is similar to that of a study by Ahmed and colleagues[15] which reported a significant improvement in MMSE after five daily sessions of high frequency rTMS (20Hz) over the DLPFC, an improvement that was maintained for three months after the end of rTMS treatments. Other studies have found that rTMS over the DLPFC has a good treatment effect on cognitive impairment in both mild AD and in moderate-to-severe AD.[27, 28] A study by Bentwich and colleagues [29] also showed a significant effect of rTMS (20 Hz) over the DLPFC in improving the scores of an auditory sentence comprehension test among patients with AD.

In this study there was no correlation between total BEHAVE-AD and ADAS-Cog scores among the 52 AD patients who completed the study, but there was a modest correlation (rs=0.33, p=0.015) between the magnitude of the improvement in cognitive symptoms (assessed by ADAS-Cog score) and the magnitude of improvement in behavioral and psychological symptoms (assessed by BEHAVE-AD) over the 4 weeks of treatment. Hollingworth and colleagues[30] consider BPSD in patients with AD a secondary cluster of symptoms directly resulting from the primary cognitive impairment, but Shinno and colleagues[31] consider BPSD and cognitive impairment two separate clusters of pathological symptoms. Our results suggest that BPSD and cognitive impairment are different, but related, pathological states.

This study, which administered high-frequency rTMS to 26 patients five days a week for four consecutive weeks, confirms previous results about the relative safety of this treatment. No seizures or other severe adverse effects were observed during the 4 weeks of treatment and there were no significant differences in the prevalence or severity of adverse reactions between the active and sham rTMS groups.

4.2. Limitations

There are several potential limitations to these results. The study has a relatively small sample size so some of the negative results, such as the failure to find significant differences for some of the subscale scores, may be due to Type II errors. We only assessed the treatment outcome at the end of the 4 weeks of rTMS treatment sessions. Follow-up studies are needed to determine a) how soon the treatment effect of rTMS manifests, b) how long the treatment effect persists after termination of the rTMS intervention, c) whether or not the effect will be greater if the rTMS is continued longer, d) whether or not rTMS can replace medication in individuals who are not tolerant to medication, and e) the appropriate interval and intensity of ‘booster sessions’ with rTMS to sustain the positive effect. We only used a single frequency (20Hz) and a single location (the DLPFC) for rTMS; additional studies will be needed to test the effect when rTMS is used at different frequencies and applied at different locations. Ultimately the goal will be to identify the parameters that can be used to tailor rTMS treatments to specific patients.

4.3. Importance

Our study found that high-frequency rTMS used as an adjunctive treatment with low-dose risperidone can significantly improve the behavioral and psychological symptoms of AD patients. Moreover, the combined treatment is more effective than medication alone for improving cognitive functioning in AD patients.

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely thank the patients who participated in the study and their caregivers.

Biography

Dr.Yue Wu graduated from Jiangnan University in 1993 and received a Master's of Medicine degree from Nanjing Medical University in 2014. She has been working in the Wuxi Mental Health Center since her graduation in 1993. Her main research interests are the early intervention of Alzheimer's disease, neurological assessment of dementia, and community rehabilitation of schizophrenia.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Wuxi Science and Technology Development Project (CSE31N1323).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Informed consent: All participants provided written informed consent.

Ethical review: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Wuxi Mental Health Center.

Authors’ contributions: WY participated in the design of the study, data collection and drafted the manuscript.XWW performed the statistical analysis and critically reviewed the manuscript.LXW carried out the clinical diagnosis and critically reviewed the manuscript.XQ and TL carried out the neurological evaluation.WSY delivered rTMS sessions.All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Dong YH, Mao XQ, Liu L, He W, Liu Y. [Prevalence of dementia among Chinese people aged 60 years and over: a meta-analysis] Zhongguo Gong Gong Wei Sheng. 2014;30(4):512–514. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seitz D, Purandare N, Conn D. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older adults in long-term care homes: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(7):1025–1039. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210000608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah A, Dalvi M, Thompson T. Behavioural and psychological signs and symptoms of dementia across cultures: current status and the future. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(12):1187–1195. doi: 10.1002/gps.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatic Association. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 2nd edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waldemar G, Dubois B, Emre M, Georges J, Mckeith IG, Rossor M, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders associated with dementia: EFNS guideline. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14 doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan MC, Chong CS, Wu AY, Wong KC, Dunn EL, Tang OW, et al. Antipsychotics and risk of cerebrovascular events in treatment of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in Hong Kong: a hospital-based, retrospective, cohort study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(4):362–370. doi: 10.1002/gps.2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Treloar A, Crugel M, Prasanna A, Solomons L, Fox C, Paton C, et al. Ethical dilemmas: should antipsycholics ever be prescribed for people with dementia? Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(2):88–90. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.076307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferreri F, Pasqualetti P, Määttä S, Ponzo D, Ferrarelli F, Tononi G, et al. Human brain connectivity during single and paired pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neuroimage. 2011;54(1):90–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoogendam JM, Ramakers GM, Di Lazzaro V. Physiology of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human brain. Brain Stimul. 2010;3(2):95–118. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solé-Padullés C, Bartrés-Faz D, Junqué C, Clemente IC, Molinuevo JL, Bargalló N, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation effects on brain function and cognition among elders with memory dysfunction. Cerebral Cortex. 2006;16(10):1487–1490. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.George MS, Lisanby SH, Avery D, McDonald WM, Durkalski V, Pavlicova M, et al. Daily left prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy for major depressive disorder: a sham-controlled randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(5):507–516. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barr MS, Farzan F, Tran LC, Fitzgerald PB, Daskalakis ZJ. A randomized controlled trial of sequentially bilateral prefrontal cortex repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Brain Stimul. 2012;5(3):337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fretas C, Mondragón-Llorca H, Pascual-Leone A. Noninvasive brain stimulation in Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and perspectives for the future. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46(8):611–627. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miniussi C, Cappa SF, Cohen LG, Floel A, Fregni F, Nitsche MA, et al. Efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation/transcranial direct current stimulation in cognitive neurorehabilitation. Brain Stimul. 2008;1(4):326–336. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed MA, Darwish ES, Khedr EM, El Serogy YM, Ali AM. Effects of low versus high frequencies of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on cognitive function and cortical excitability in Alzheimer’s dementia. J Neurol. 2012;259(1):83–92. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pennisi G, Ferri R, Cantone M, Lanza G, Pennisi M, Vinciguerra L, et al. A review of transcranial magnetic stimulation in vascular dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2011;31(1):71–80. doi: 10.1159/000322798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer′s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer′s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer′s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reisberg B, Auer SR, Monteiro IM. Behavioral pathology in Alzheimer’s disease (BEHAVE-AD) rating scale. Int Psychogeriatr. 1996;8 doi: 10.1017/s1041610296002621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pena-Casanova J. Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive in clinical practice. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hao WP, Ye FH, Li LZ, Wu XR, Ma L, Wang L. [The efficacy of risperidone intervention for behavioral and psychological symptoms of Alzheimer dementia] Zhong Hua Lao Nian Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2007;7(26):510–512. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng DT, Zhu R, Yuan XR, Zhang Y. [Clinical study of deep brain magnetic stimulation technique in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease] Zhong Hua Lao Nian Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2012;31(11):929–930. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Y, Gu J, Leng WJ, Huang H, Zhao XQ. The Thirteenth National Conference on Behavioral Medicine. Ningxia: Yinchuan: Chinese Medical Association.; 2011 August 1. [Clinical study of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms in patients with Alzheimer's] pp. 672–673. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onor ML, Saina M, Trevisiol M, Cristante T, Aguglia E. Clinical experience with risperidone in the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Prog Neuropsychophamacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(1):205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker D, Hershkowitz M, Maidler N, Rabinowitz M, Floru S. Psychopathology and cognitive decline in dementia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1994;182(12):701–703. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slotema CW, Aleman A, Daskalakis ZJ, Sommer IE. Meta-analysis of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of auditory verbal hallucinations: update and effects after one month. Schizophr Res. 2012;142(1-3):40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cotelli M, Manenti R, Cappa F, Zanetti O, Miniussi C. Transcranial magnetic stimulation improves naming in Alzheimer disease patients at different stages of cognitive decline. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(12):1286–1292. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cotelli M, Calabria M, Manenti R, Rosini S, Zanetti O, Cappa SF, et al. Improved language performance in Alzheimer disease following brain stimulation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(7):794–797. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.197848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bentwich J, Dobronevsky E, Aichenbaum S, Shorer R, Peretz R, Khaigrekht M, et al. Beneficial effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with cognitive training for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a proof of concept study. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2011;118(3):463–471. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0578-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollingworth P, Hamshere ML, Moskvina V, Dowzell K, Moore PJ, Foy C, et al. Four components describe behavioral symptoms in 1120 individuals with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(9):1348–1354. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shinno H, Inagaki T, Miyaoka T, Okazaki S, Kawamukai T, Utani E, et al. A decrease in N-acetylaspartate and an increase in myoinositol in the anterior cingulate gyrus are associated with behavioral and psychological symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2007;260(1-2):132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]