Abstract

Intravenous ganciclovir and, increasingly, oral valganciclovir are now considered the mainstay of treatment for cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection or CMV disease. Under certain circumstances, CMV immunoglobulin (CMVIG) may be an appropriate addition or, indeed, alternative. Data on monotherapy with CMVIG are limited, but encouraging, for example in cases of ganciclovir intolerance. In cases of recurrent CMV in thoracic transplant patients after a disease- and drug-free period, adjunctive CMVIG can be considered in patients with hypogammaglobulinemia. Antiviral-resistant CMV, which is more common among thoracic organ recipients than in other types of transplant, can be an indication for introduction of CMVIG, particularly in view of the toxicity associated with other options, such as foscarnet. Due to a lack of controlled trials, decision-making is based on clinical experience. In the absence of a robust evidence base, it seems reasonable to consider the use of CMVIG to treat CMV in adult or pediatric thoracic transplant patients with ganciclovir-resistant infection, or in serious or complicated cases. The latter can potentially include (i) treatment of severe clinical manifestations, such as pneumonitis or eye complications; (ii) patients with a positive biopsy in end organs, such as the lung or stomach; (iii) symptomatic cases with rising polymerase chain reaction values (for example, higher than 5.0 log10) despite antiviral treatment; (iv) CMV disease or CMV infection or risk factors, such as CMV-IgG–negative serostatus; (vi) ganciclovir intolerance; (vii) patients with hypogammaglobulinemia.

Treatment Strategies for CMV Events After Thoracic Transplantation

The incidence of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection after heart transplantation is similar to that in kidney or liver transplantation, with estimates ranging from 9% to 35%,1 but the risk of progression to CMV disease is markedly higher.1 One study observed a 25% risk of developing biopsy-confirmed CMV disease during the first year posttransplant in high-risk CMV-seronegative heart transplant recipients.2 The highest rates of both CMV infection and CMV disease—approximately 40%—are seen in lung and heart-lung transplant patients.3 Treatment strategies aim to avoid progression to organ involvement and development of opportunistic infections and to reduce CMV-related complications, such as graft rejection.

Intravenous (IV) ganciclovir and oral valganciclovir are the mainstay of treatment for CMV infection or CMV disease after solid organ transplantation. In a population of mixed solid organ transplant recipients, the VICTOR study showed CMV viremia to be eradicated in approximately 70% of cases by week 7 using either therapy.4 However, antiviral therapy does not achieve viral clearance in all patients even when exposure is confirmed to be adequate.5,6 Late-onset CMV disease, defined as occurring after cessation of prophylaxis, is of particular concern. Studies have suggested the incidence of late-onset CMV to be 29% and 49% in D+/R− recipients of heart7,8 and lung9 transplants, respectively, with an increased risk if only a short course of antiviral prophylaxis is given10,11 compared with extended antiviral prophylaxis.12 In cases of late-onset CMV infection, an antiviral treatment course followed by secondary prophylaxis for one to three months is recommended,13 and is usually adequate to control the infection. Other interventions may, however, become necessary if invasive disease develops or ganciclovir resistance emerges. In addition, prolonged therapy of ganciclovir may lead to severe toxicity, of which bone marrow toxicity with severe cytopenia is the most feared complication.14

There are circumstances where the use of CMV immunoglobulin (CMVIG) may be an appropriate addition to ganciclovir and valganciclovir administration, although data are currently highly limited. Of note, negative CMV IgG serostatus at the start of antiviral treatment in the VICTOR study of patients who had received various types of solid organ transplant was associated with a significantly higher rate of recurrent disease compared with seropositive patients (27.6% vs 13.0%; P = 0.039), that is, an adequate anti-CMV IgG level is important for mounting an effective anti-CMV response.4 Although the main commercially available CMVIG preparations, Cytotect or Cytogam, are licensed only for prophylactic use, some centers use CMVIG off-label to support the treatment of CMV infection or disease, for example, in patients with hypogammaglobulinemia, in the event of ganciclovir resistance, or in the event of tissue-invasive disease. This article considers the available evidence concerning use of CMVIG to treat CMV infection or CMV disease after thoracic transplantation (Tables 1 and 2).

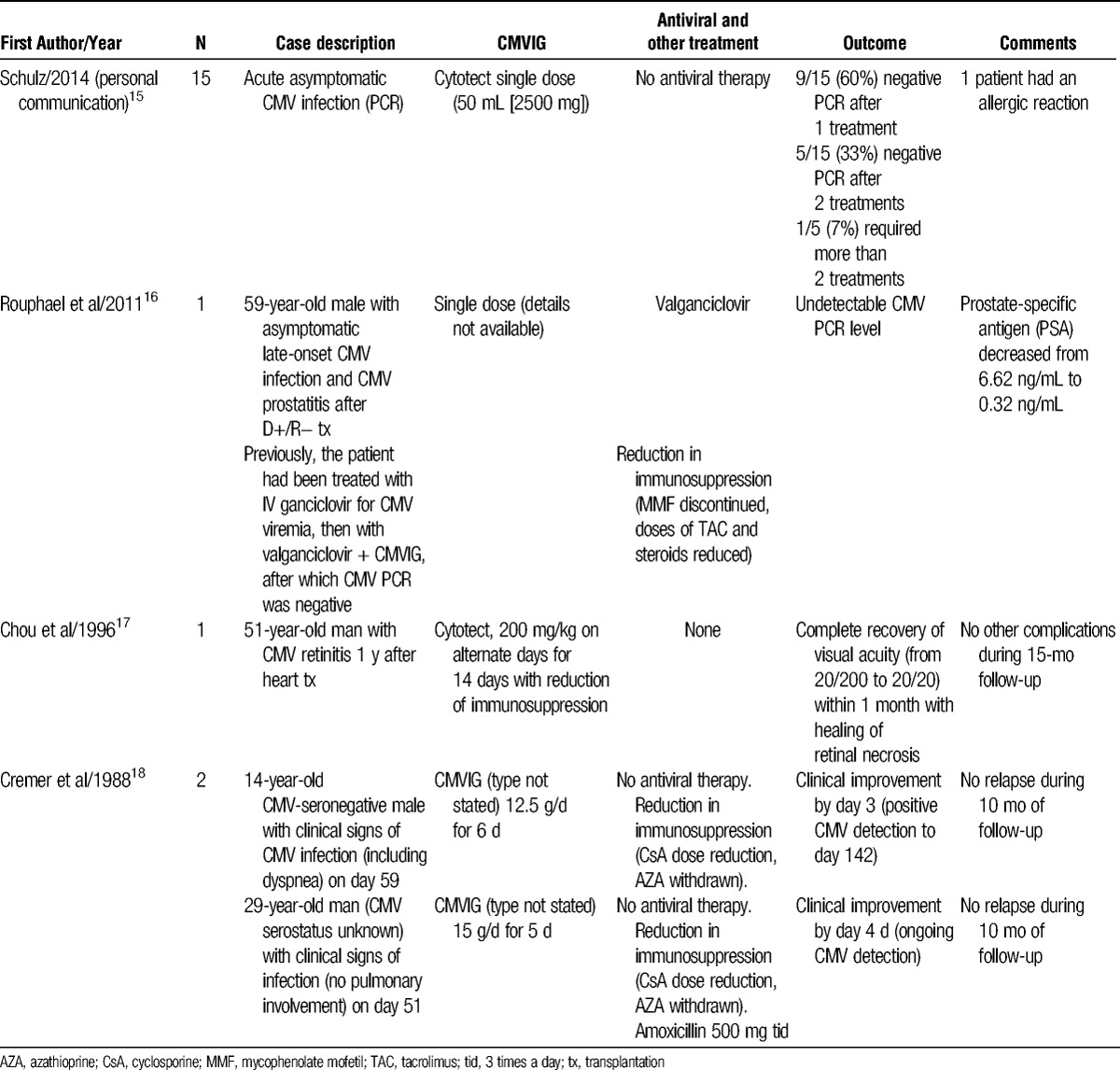

TABLE 1.

Experience with CMVIG treatment for CMV infection or CMV disease in heart transplantation

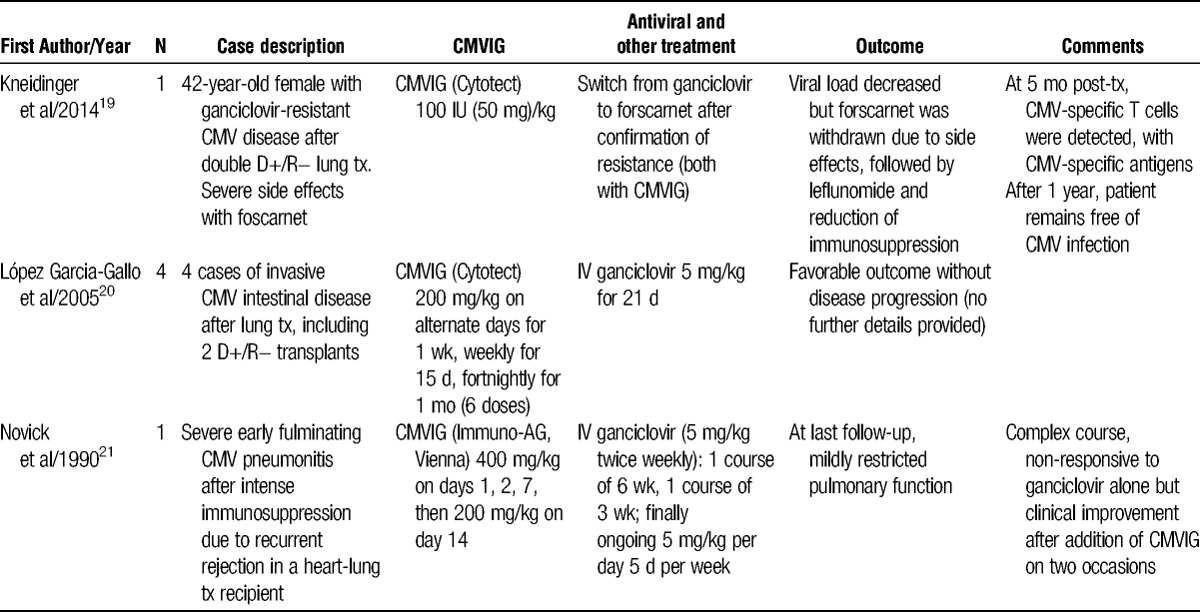

TABLE 2.

Experience with CMVIG treatment for CMV infection or CMV disease in lung and heart-lung transplantation

CMVIG in Uncomplicated Cases

Although antiviral agents remain the cornerstone for routine management of CMV infection or CMV disease, CMVIG has been used as an alternative in asymptomatic cases. In a series of 15 asymptomatic heart transplant recipients who had acute CMV infection with no CMV disease and low viral load (defined as 500-1000 CMV DNA copies/mL detected by polymerase chain reaction [PCR]), Schulz et al15 administered a single low dose of 50 mL Cytotect without antiviral therapy. In 14 cases, viral clearance was achieved. In 1 patient, a second 50-mL dose was given after the next PCR test continued to show a viral load in the range of 500 to 1000 CMV DNA copies/mL. Five patients subsequently relapsed, showing positive CMV viremia, and received another single 50-mL dose. No antiviral therapy was given. Over half the patients (9/15, 60%) were found to be CMV-negative after just 1 dose, with all but 1 clearing CMV infection with 2 doses. These encouraging results merit further investigation.

There are also published cases in which CMVIG has been used to treat symptomatic CMV disease without concomitant antiviral therapy.17,18 In an early report, Cremer et al18 described 2 heart transplant recipients who were not given any antiviral therapy, and who presented with clinical symptoms consistent with CMV infection (Table 1). In the first case, symptoms including dyspnea and pulmonary infection developed on day 59 posttransplant in a 14-year CMV-seronegative boy. The CMVIG was started (12.5 g on 6 consecutive days), and immunosuppression was reduced (cyclosporine concentration was reduced from 600 ng/mL to 350 ng/mL and azathioprine was withdrawn). Symptoms improved within 3 days. The second case was a 29-year-old with CMV viremia who presented with malaise, subfebrile raised temperature, epigastric pain, and nausea but no pulmonary involvement. The CMVIG was administered at a dose of 15 g for 5 consecutive days, accompanied by cyclosporine reduction and azathioprine discontinuation, leading to clinical improvement by day 4 and hospital discharge by day 7. In both cases, there was no sign of relapse after 10 months of follow-up.18 In another published case report, a 51-year-old man was found to have CMV-related retinitis 1 year after heart transplantation.17 Antiviral therapy was not instituted due to the clinician's concern about relapse and the need for maintenance therapy. Instead, the patient was successfully treated with CMVIG (Cytotect, 200 mg/kg every other day for 2 weeks) and reduced intensity of immunosuppression (Table 1).

López Garcia-Gallo et al20 have briefly described 4 cases in which lung transplant recipients who developed invasive CMV-related intestinal disease were treated with CMVIG (200 mg/kg every 2 days for a week, weekly for a further 2 weeks, then once every 2 weeks for a month) in combination with IV ganciclovir (Table 2). Two of the patients received a D+/R− transplant, with gastritis and hepatitis diagnosed at 16 and 18 months posttransplant, respectively. All 4 cases evolved favorably.

Intolerance to antiviral therapy can also represent a suitable occasion for introduction of CMVIG. Rouphael et al16 recently described the case of a 59-year-old male recipient of a D+/R− heart transplant. Based on a preemptive management protocol, a CMV level of 10 400 copies/mL on PCR at week 6 posttransplant triggered treatment with IV ganciclovir for 6 weeks, which lowered CMV level to 2900 copies/mL. Oral valganciclovir was started. However, the patient developed neutropenia and valganciclovir had to be withdrawn for 2 weeks. At this point, CMVIG was added once a month for 6 months (the dose was not stated), and after 3 months, the patient was CMV-negative.16

Recurrent CMV Infections

Despite high rates of response when CMV disease is treated with IV ganciclovir or valganciclovir,6,22,23 recurrence remains a problem.24 Across all organ types, 1 study reported recurrent CMV viremia or disease in 27% of patients within approximately 2.5 years after completion of a treatment course comprising IV ganciclovir and oral valganciclovir.25 Risk factors for recurrent CMV infection include primary CMV infection (ie, D+/R− recipients), CMV-IgG negative serostatus, high initial viral load, slow viral response to treatment, persistent viremia during secondary prophylaxis, and antirejection therapy during anti-CMV treatment.13,23

Isada et al26 described 13 cases of solid organ transplant patients with ganciclovir-resistant CMV infection, pointing out that 6 of the patients had received only oral ganciclovir and 5 had received intermittent IV ganciclovir prophylaxis, highlighting the need for therapeutic exposure levels. Conventional short treatment courses are now being extended at many centers in an attempt to avoid recurrence.27

Recurrent episodes of CMV disease do not always respond to additional antistatic treatment22 or modification of the immunosuppression regimen, and the 2013 CMV Consensus Conference of The Transplantation Society recommends that in cases of recurrent CMV in thoracic transplant patients after a disease- and drug-free period, adjunctive CMVIG can be considered in patients with hypogammaglobulinemia. Many thoracic transplant patients receive mycophenolic acid immunosuppression, which inhibits T- and B-cell proliferation, suppressing expression of adhesion molecules,28 and can induce hypogammaglobulinemia. Novick et al21 have reported a case in which a patient developed severe pulmonary rejection 3 weeks after receipt of a D+/R− heart-lung transplant, requiring IV steroids and OKT3. The CMV pneumonitis was detected, at which point the patient was leukopenic. Intravenous ganciclovir did not lead to clinical or radiologic improvement until after addition of CMVIG (400 mg/kg on days 1, 2, and 7; 200 mg/kg on day 14). Four months later, she developed shortness of breath, and CMV was detected in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Another 3-week course of IV ganciclovir with concomitant CMVIG was initiated, leading to resolution of symptoms, and she was subsequently maintained on IV ganciclovir as an outpatient.

Ganciclovir-Resistant CMV Infection

Nonresponse to antiviral therapy may indicate the presence of viral resistance. Antiviral-resistant CMV is more common among thoracic organ recipients than other types of solid organ transplantation,24 and often has an unfavorable clinical outcome29,30 including tissue-invasive disease.13 The incidence of resistance has been estimated to be between 0.25% and 5.3% after heart transplantation, and between 2.2% and 15.2% in lung transplant patients.24 Resistance is more frequent in D+/R− recipients.30,31 One single-center analysis of 274 heart transplant patients transplanted during 1995 to 2006 found a 1.5% incidence of ganciclovir-resistant CMV disease overall (5% among D+/R− patients), which was associated with prolonged CMV-related hospitalization.31 In lung transplantation, full or partial resistance has been reported in between 5%32 and 9%33 of patients and is associated with shorter survival and early onset of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome.32 Inadequate antiviral exposure can lead to resistance,13 and most cases have been reported in patients given oral ganciclovir rather than IV ganciclovir or valganciclovir, suggesting that inadequate exposure may contribute, although resistance to valganciclovir is not unknown.34 In 1 series of 5 lung transplant patients with CMV infection who showed a persistent poor response to ganciclovir, ganciclovir levels were found to be subtherapeutic and genotyping confirmed ganciclovir-resistant CMV.35 Longer exposure to ganciclovir levels that does not completely inhibit CMV replication can lead to sudden appearance of resistance31,32,36,37 particularly in D+/R− recipients given intensive immunosuppressive regimens.38 There are few therapeutic options for ganciclovir-resistant CMV infections. Foscarnet is the most frequent choice, but is used off-label in this setting and is limited by severe bone marrow and renal toxicity. No other therapies are approved for ganciclovir-resistant CMV infection.

There are no controlled studies comparing different management strategies for ganciclovir-resistant CMV disease. Moreover, decision-making often has to be based on clinical suspicion of resistance because of the time required for laboratory confirmation. The most common mutation (UL97) usually appears in isolation without cross-resistance to the other antivirals licensed for CMV treatment, that is, cidofovir or foscarnet. However, the combination of UL97 and UL54 mutations usually confers cross-resistance to cidofovir. Foscarnet is considered the antiviral agent of choice in cases of ganciclovir-resistant CMV disease; however, even with the introduction of foscarnet, survival rates can be low in thoracic transplant patients,26,30 and toxicity is high.30 Other approaches include introduction of a non–CMV-specific agent (leflunomide or artesunate) or switch to mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition immunosuppression but these remain poorly documented.13

In cases of suspected ganciclovir-resistant CMV infection where the patient is asymptomatic or not severely ill, increased ganciclovir exposure with CMVIG and reduced immunosuppressive therapy have been proposed. Complete discontinuation of immunosuppression is impracticable after thoracic transplantation.

Hypogammaglobulinemia

To date, published results for treatment with CMVIG therapy in patients with CMV infection and hypogammaglobulinemia are lacking. One center has reported the effect of nonspecific IV immunoglobulin (Ig) treatment for severe infections in heart transplant patients with hypogammaglobulinemia (mean IgG 480 mg/dL).39 In the subpopulation of 24 patients with CMV disease, 10 of whom received IV Ig, the mortality rate was 20% compared with 71% in the 14 patients without IV Ig therapy (odds ratio, 0.06; 95% confidence interval, 0.006-0.63; P = 0.01). Another report has described outcomes in 5 heart transplant patients with hypogammaglobulinemia, and recurrent CMV disease was treated with IV infusions of pooled human IG (200-400 mg/g per cycle) every 3 weeks until at least 3 months after a negative assay for CMV antigenemia.40 Batches with the highest anti-CMV titers were selected for use. Patients also received IV ganciclovir. All patients became negative for CMV antigenemia, at a mean of 34 days after the first infusion, and symptoms resolved with no adverse events.

Reduction of antiproliferative immunosuppressive agents, notably mycophenolic acid, is an alternative approach to restoring IgG levels in patients with hypogammaglobulinemia and is an economical strategy. Use of IVIG, while not providing the same degree of anti-CMV antibody protection, may also be adequate in many cases and could offer a more cost-effective approach to CMVIG although a benefit for IVIG in the management of both CMV infections and acute rejections has not been confirmed.

Case Study

A 30-year-old woman received a high-urgency heart transplant on March 19, 2010. Two years before referral to the transplant center, she was diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy, probably caused by myocarditis, according to an endomyocardial biopsy performed elsewhere. While awaiting transplantation, her heart failure syndrome progressed rapidly, necessitating introduction of inotrope therapy followed by insertion of an intra-aortic balloon pump and, finally, on March 3, she received venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

The donor, a 55-year-old woman, who died after cerebral hemorrhage, was seropositive for CMV, whereas the recipient was CMV-negative.

The postoperative course was characterized by severe renal impairment which required continuous veno-venous hemofiltration, and by moderate right ventricle dysfunction secondary to pretransplant reactive pulmonary hypertension.

Induction therapy comprised basiliximab (Simulect; Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland) administered on day 0 and day 4, with maintenance therapy based on mycophenolate mofetil (Cellcept; Roche Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland) and prednisone, started on day 2. Due to the severe renal impairment, cyclosporine (Neoral; Novartis Pharma AG) was started at a very low dose only on postoperative day 13 after a second protocol endomyocardial biopsy showed grade 3A cellular rejection. Graft rejection characterized the patient's course. She was resistant to steroids and 3 consecutive biopsies indicated grade 3A rejection despite intensive steroid therapy and increasing cyclosporine exposure.

The patient received anti-CMV prophylaxis with valganciclovir 450 mg every second day, based on her renal function. Despite this, she developed a primary CMV infection during valganciclovir treatment on April 19. CMV DNA PCR testing of whole blood was positive, at 500 copies/mL, with the titer rising to 6500 copies/mL on April 26. At that point, her measured creatinine clearance was only 10 mL/min so the valganciclovir could not be increased. The patient was in very poor condition, weighing only 40 kg with a BMI of 18 kg/m2. In response to the primary CMV infection, she was switched from valganciclovir to low-dose ganciclovir (1 mg/kg per day) combined with CMVIg (Cytotect, Biotest AG, Dreieich, Germany). The dose of CMVIg was an empirically defined ‘intensive’ regimen of 50 U/kg given every second day for a total of four doses.

During a myocardial biopsy procedure the tricuspid valve was damaged, causing severe tricuspid regurgitation followed by refractory right heart failure. This ultimately required surgery for tricuspid valve repair on April 29. During surgery another biopsy sample was taken and revealed ongoing grade 3A rejection. However, the cellular infiltrate was very rich in plasma cells, supporting the suspicion of concomitant parvovirus B19 infection which was later confirmed by myocardial and blood PCR.

The patient received another course of steroids and CMVIg (50 U/kg) was continued twice weekly from May 2 to May 14. The CMV DNA peaked on May 6 at 18 100 copies/mL during combined treatment with ganciclovir and CMVIg treatment, then started to decline before becoming negative on June 17. Ganciclovir was discontinued on June 21.

After the tricuspid valve repair, repeat biopsy was not feasible. The presence of rejection was monitored by measuring graft function with ultrasound and by screening for myocardial edema (which is suggestive of possible rejection) using cardiac magnetic resonance. These 2 noninvasive, albeit indirect, monitoring techniques did not suggest significant myocardial rejection relapse. Throughout the patient's course, she remained negative for donor-specific antibodies.

The patient was discharged from the hospital on June 21.

This case reflects the complexity of managing heart transplantation in an extremely ill and frail patient. Coexistence of multiple comorbidities and procedural complications prevented administration of adequate CMV prophylactic antiviral therapy, further worsening the clinical situation. In this patient, CMVIG was used off-label as adjuvant therapy to treat a primary CMV infection, at a dosage significantly higher than that typically recommended for CMV prophylaxis. There were no adverse events associated with CMVIG treatment.

The breakthrough CMV infection during valganciclovir prophylaxis may have been due to viral resistance, a possibility that was not investigated with molecular testing. Based on the clinical course, however, it was more likely caused by inadequate valganciclovir dosing necessitated by the presence of severe renal dysfunction, coupled with a severely suppressed immune system. In this context, the use of CMVIG is likely to have made a substantial contribution to controlling CMV infection when added to ganciclovir therapy. Notably, the usual dose of ganciclovir when used to treat CMV infection in patients with normal renal function is 2.5 mg/kg twice per day, whereas here, the dose was 5 times lower. In addition, it could be speculated that due to the immunomodulatory properties of immunoglobulins, use of high-dose CMVIG may have positively modulated the immune response, since no further signs of rejection were detected despite a previous succession of steroid-resistant rejection episodes.

This case does not permit any conclusions about the role of CMVIG beyond those specified on the product label. However, it raises important hypotheses about its immunomodulatory properties and efficacy as adjuvant therapy that merit further investigation in appropriately designed prospective studies.

CONCLUSIONS

There is a pressing need for more rigorous comparative data to define the optimal role for CMVIG therapy for CMV treatment which balances the clinical benefit versus the additional cost of therapy. Based on the current limited evidence base, the use of CMVIG to treat CMV in adult or pediatric thoracic transplant patients appears to be most appropriate for ganciclovir-resistant infection or in serious or complicated cases. The latter can potentially include (i) treatment of severe clinical manifestations, such as pneumonitis or eye complications; (ii) patients with a positive biopsy in end organs, such as the lung or stomach; (iii) symptomatic cases with rising PCR values (eg, higher than 5.0 log10) despite antiviral treatment; (iv) CMV disease or CMV infection with severe leukopenia (eg, arising from antiviral treatment); (v) recurrent CMV infection or risk factors, such as CMV-IgG negative serostatus; (vi) ganciclovir intolerance; (vii) or patients with hypogammaglobulinemia. There is no consensus on the optimal CMVIG regimen when used as a treatment for CMV infection or CMV disease, but dosages are higher than for prophylactic use, with 200 to 400 mg/kg being typical.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are grateful to Luciano Potena, Heart and Lung Transplant Program, Cardiovascular Department, Academic Hospital Sant' Orsola Malpighi Bologna, Bologna, Italy, for contributing this case study.

Footnotes

This supplement was funded by Biotest AG, Dreieich, Germany.

All authors received an honorarium from Biotest AG to attend the meeting upon which this publication is based. Veronika Müller has received a travel grant from Biotest AG.

All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

All authors attended a meeting to discuss the content of this supplement and review the available evidence, after which the article was developed by a freelance medical writer. All authors undertook a detailed critique of draft texts and approved the final manuscript for submission.

REFERENCES

- 1. Roman A, Manito N, Campistol JM, et al. The impact of the prevention strategies on the indirect effects of CMV infection in solid organ transplant recipients. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2014; 28: 84– 91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mendez-Eirin E, Paniagua-Martín MJ, Marzoa-Rivas R, et al. Cumulative incidence of cytomegalovirus infection and disease after heart transplantation in the last decade: effect of preemptive therapy. Transplant Proc. 2012; 44: 2660– 2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McDevitt LM. Etiology and impact of cytomegalovirus disease on solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006; 63(19 Suppl 5): S3– S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Asberg A, Humar A, Rollag H, et al. Oral valganciclovir is noninferior to intravenous ganciclovir for the treatment of cytomegalovirus disease in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2007; 7: 2106– 2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perrottet N, Manuel O, Lamoth F, et al. Variable viral clearance despite adequate ganciclovir plasma levels during valganciclovir treatment for cytomegalovirus disease in D+/R− transplant recipients. BMC Infect Dis. 2010; 10: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fellay J, Venetz JP, Aubert JD, et al. Treatment of cytomegalovirus infection or disease in solid organ transplant recipients with valganciclovir. Transplant Proc. 2005; 37: 949– 951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kijpittayarit-Arthurs S, Eid AJ, Kremers WK, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of delayed-onset primary cytomegalovirus disease in cardiac transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007; 26: 1019– 1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Humar A, Mazzulli T, Moussa G, et al. Clinical utility of cytomegalovirus (CMV) serology testing in high-risk CMV D+/R− transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2005; 5: 1065– 1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schoeppler KE, Lyu DM, Grazia TJ, et al. Late-onset cytomegalovirus (CMV) in lung transplant recipients: can CMV serostatus guide the duration of prophylaxis? Am J Transplant. 2013; 13: 376– 382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Humar A, Lebranchu Y, Vincenti F, et al. The efficacy and safety of 200 days valganciclovir cytomegalovirus prophylaxis in high-risk kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2010; 10: 1228– 1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gupta S, Mitchell JD, Markham DW, et al. High incidence of cytomegalovirus disease in D+/R− heart transplant recipients shortly after completion of 3 months of valganciclovir prophylaxis. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008; 27: 536– 539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Humar A, Limaye AP, Blumberg EA, et al. Extended valganciclovir prophylaxis in D+/R− kidney transplant recipients is associated with long-term reduction in cytomegalovirus disease: two-year results of the IMPACT study. Transplantation. 2010; 90: 1427– 1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kotton CN, Kumar D, Caliendo AM, et al. Updated international consensus guidelines on the management of cytomegalovirus in solid-organ. Transplantation. 2013; 96: 333– 360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crumpacker CS. Ganciclovir. N Engl J Med. 1996; 335: 721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Personal Communication, U Schulz, Ruhr University Bochum, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

- 16. Rouphael NG, Laskar SR, Smith A, et al. Cytomegalovirus prostatitis in a heart transplant recipient. Am J Transplant. 2011; 11: 1330– 1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chou PI, Lee H, Lee FY. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after heart transplant: a case report. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 1996; 57: 310– 313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cremer J, Schäfers HJ, Wahlers T, et al. Hyperimmunoglobulin treatment in CMV infections following heart transplantation. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1988; 113: 18– 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kneidinger N, Giessen C, von Wulffen W, et al. Trip to immunity: resistant cytomegalovirus infection in a lung transplant recipient. Int J Infect Dis. 2014; 28: 140– 142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. López Garcia-Gallo C, Ussetti Gil P, Laporta R, et al. Is gammaglobulin anti-CMV warranted in lung transplantation? Transplant Proc. 2005; 37: 4043– 4045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Novick RJ, Menkis AH, McKenzie N, et al. Should heart-lung transplant donors and recipients be matched according to cytomegalovirus serologic status? J Heart Transplant. 1990; 9: 699– 706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Keay S, Petersen E, Icenogle T, et al. Ganciclovir treatment of serious cytomegalovirus infection in heart and heart-lung transplant recipients. Rev Infect Dis. 1988; 10(Suppl 3): S563– S572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Falagas ME, Snydman DR. Recurrent cytomegalovirus disease in solid-organ transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 1995; 27(5 Suppl 1): 34– 37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Snydman DR, Limaye AP, Potena L, et al. Update and review: state-of-the-art management of cytomegalovirus infection and disease following thoracic organ transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2011; 43(3 Suppl): S1– S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eid AJ, Arthurs SK, Deziel PJ, et al. Clinical predictors of relapse after treatment of primary gastrointestinal cytomegalovirus disease in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2010; 10: 157– 161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Isada CM, Yen-Lieberman B, Lurain NS, et al. Clinical characteristics of 13 solid organ transplant recipients with ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus infection. Transpl Infect Dis. 2002; 4: 189– 194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jaksch P, Zweytick B, Kerschner H, et al. Cytomegalovirus prevention in high-risk lung transplant recipients: comparison of 3- vs 12-month valganciclovir therapy. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009; 28: 670– 675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Allison AC, Eugui EM. Mycophenolate mofetil and its mechanisms of action. Immunopharmacology. 2000; 47: 85– 118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boivin G, Goyette N, Rollag H, et al. Cytomegalovirus resistance in solid organ transplant recipients treated with intravenous ganciclovir or oral valganciclovir. Antivir Ther. 2009; 14: 697– 704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Minces LR, Nguyen MH, Mitsani D, et al. Ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus infections among lung transplant recipients are associated with poor outcomes despite treatment with foscarnet-containing regimens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014; 58: 128– 135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li F, Kenyon KW, Kirby KA, et al. Incidence and clinical features of ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus disease in heart transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 45: 439– 447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kruger RM, Shannon WD, Arens MQ, et al. The impact of ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus infection after lung transplantation. Transplantation. 1999; 68: 1272– 1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Limaye AP, Raghu G, Koelle DM, et al. High incidence of ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus infection among lung transplant recipients receiving preemptive therapy. J Infect Dis. 2002; 185: 20– 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Eid AJ, Arthurs SK, Deziel PJ, et al. Emergence of drug-resistant cytomegalovirus in the era of valganciclovir prophylaxis: therapeutic implications and outcomes. Clin Transplant. 2008; 22: 162– 170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gagermeier JP, Rusinak JD, Lurain NS, et al. Subtherapeutic ganciclovir (GCV) levels and GCV-resistant cytomegalovirus in lung transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2014; 16: 941– 950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Emery VC, Griffiths PD. Prediction of cytomegalovirus load and resistance patterns after antiviral chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000; 97: 8039– 8044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zamora MR. Controversies in lung transplantation: management of cytomegalovirus infections. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2002; 21: 841– 849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Limaye AP, Corey L, Koelle DM, et al. Emergence of ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus disease among recipients of solid-organ transplants. Lancet. 2000; 356: 645– 649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Carbone J, Sarmiento E, Palomo J, et al. The potential impact of substitutive therapy with intravenous immunoglobulin on the outcome of heart transplant recipients with infections. Transplant Proc. 2007; 39: 2385– 2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sarmiento E, Rodriguez-Molina J, Muñoz P, et al. Decreased levels of serum immunoglobulins as a risk factor for infection after heart transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005; 37: 4046– 4049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]