Abstract

Recent studies reported increased (Pro)renin receptor (PRR) expression during low-salt intake. We hypothesized that PRR plays a role in regulation of renal epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) through serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase isoform 1 (SGK-1)-neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally downregulated 4–2 (Nedd4–2) signaling pathway. Male Sprague–Dawley rats on normal-sodium diet and mouse renal inner medullary collecting duct cells treated with NaCl at 130 mmol/l (normal salt), or 63 mmol/l (low salt) were studied. PRR and α-ENaC expressions were evaluated 1 week after right uninephrectomy and left renal interstitial administration of 5% dextrose, scramble shRNA, or PRR shRNA (n = 6 each treatment). In-vivo PRR shRNA significantly reduced expressions of PRR throughout the kidney and α-ENaC subunits in the renal medulla. In inner medullary collecting duct cells, low salt or angiopoietin II (Ang II) augmented the mRNA and protein expressions of PRR (P < 0.05), SGK-1 (P < 0.05), and α-ENaC (P < 0.05). Low salt or Ang II increased the phosphorylation of Nedd4–2. In cells treated with low salt or Ang II, PRR siRNA significantly downregulated the mRNA and protein expressions of PRR (P < 0.05), SGK-1 (P < 0.05), and α-ENaC expression (P < 0.05). We conclude that PRR contributes to the regulation of α-ENaC via SGK-1-Nedd4–2 signaling pathway.

Keywords: epithelial sodium channel, (Pro)renin receptor, renal sodium regulation

INTRODUCTION

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) plays an essential role in the regulation of blood pressure, renal hemodynamic function, and tubular sodium reabsorption. (Pro)renin receptor (PRR) is a recently discovered component of the RAS, and binds to renin and prorenin with almost equal affinity and enhance their catalytic activities [1]. It is a 350-amino acid single transmembrane protein and localized in diverse kidney structures, mainly in mesangial cells (RMC), podocytes, renal vasculature, proximal (RPT) and distal (RDT) tubules, and collecting ducts [1–4]. Although PRR was discovered over a decade ago [2], its physiologic functions are not well elucidated.

The amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channel (EN-aC) is an important transporter that plays a critical role in maintaining Na+ homoeostasis by enhancing its absorption [3]. ENaC comprises of three subunits: α, β, and γ [4] that are highly expressed in renal tubules [5]. It is expressed in distal convoluted tubules and collecting ducts [5–6]. The expression of ENaC subunits was shown to increase with low-salt intake [7]. Of the three subunits, α-ENaC is critical for the channel activity [4]. β and γ-ENaC subunits were shown to complement the function of α-ENaC [4]. Even though proximal tubule is responsible for reabsorbing the bulk of sodium, it is the distal nephron that is responsible for fine-tuning the rate of urine formation and its composition. Currently, there is a viable evidence that the serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase isoform 1 (SGK-1) contributes to the signal transduction cascade of epithelial sodium transport and via the control of ENaC activity and expression at the cell surface [8]. However, ENaC activation by SGK-1 is rather complex. A fundamental role of SGK-1 is to increase the cell surface expression of ENaC [16] by inhibiting the ubiquitin ligase neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally down-regulated 4–2 (Nedd4–2) [9–10]. Binding of Nedd4–2 to ENaC leads to ubiquitination of lysine residues in the N terminus of the channel and to internalization of sodium channel and proteasomal degradation. SGK-1 binds through its PY motif to a WW domain of Nedd4–2 and weakens the interaction between ENaC and Nedd4–2, and therefore reducing ENaC ubiquitination, which results in the increased expression of ENaC and increased Na+ reabsorption [11].

The contribution of PRR in regulation of renal α-ENaC is unknown. Recent, in-vivo and in-vitro studies from our laboratory demonstrated an increase in renal PRR expression in distal tubules with low sodium exposure [12–13]. In the present study, we hypothesized that PRR contributes to regulation of α-ENaC expression in collecting duct via SGK-1-Nedd4–2 signaling pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal preparation

The University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee approved all study protocols. Experiments were conducted in male Sprague–Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Massachusetts, USA) weighing 200–250 g. Animals were allowed 1 week to adjust to our animal care facility. Rats were provided tap water ad libitum and fed normal-sodium) diet (Harlan-Teklad, Madison, WI). Rats were allocated into three treatment groups (n = 6 each group); 5% dextrose in water, scramble shRNA, or PRR shRNA, and were placed in individual metabolic cages for a period of 24 h for urine collections on day 0 (baseline) and day 7.

Surgical procedures, dose response, and treatment administration

Right uninephrectomy and administration of different treatments were done as described in the supplement methods section, http://links.lww.com/HJH/A566.

On day 7 posttreatments, animals were anesthetized as stated above and endotracheal tube was inserted to maintain an open airway. Blood samples were collected from carotid artery in heparinized tubes [14–15]. Plasma samples were aliquoted and stored at −20°C until analyzed. To insure that PRR shRNA treatment was confined to the kidney, the heart was harvested and stored in −80°C until analyzed for measurement of PRR mRNA and protein expression.

Blood pressure, renal blood flow glomerular filtration rate, and urinary sodium

Blood pressure (BP) was assessed on day 0 (baseline) and day 7 of study as previously described [12] in nonanesthetized rats using a tail-cuff noninvasive multichannel blood pressure system (IITC Life Sciences, Woodland Hills, California, USA). Changes in renal cortical and medullary blood flow were determined by laser flowmeter (Advance Laser Flowmeter ALF 21D, Tokyo, Japan) as described earlier [16–17]. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was measured based on inulin clearance as previously described [18–19]. Urinary sodium concentration was measured using flame photometer IL 943 (Instrumentation Laboratory, Bedford, Massachusetts, USA).

Cell culture

Mouse renal inner medullary collecting duct epithelial cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, Virginia, USA) and cultured according to American Type Culture Collection recommended protocols. Low-salt media were prepared according to Yang’s methods [20]. Low-salt medium was prepared by Opti-MEM I medium in a 1 : 1 mixture with 300 mmol/l D-mannitol (to reduce Na+ concentration to 63.00 mmol/l). Osmolality was maintained by adding 300 mmol/l D-Mannitol to the culture media and was measured at 290 mOsmol/kg [21]. In control groups, cells were exposed to Opti-MEM I medium (final Na+ concentration about 130.00 mmol/l). Cells were exposed to normal salt or low-salt medium for 48 h, respectively. For angiopoietin II (Ang II) treatment, cells were starved overnight and Ang II (0.1 μmol/l; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Luis, Missouri, USA) was added to serum-free medium 30 min prior to the end of serum starvation. After 30 min pretreatment, cells were refreshed with normal salt medium with or without Ang II for 48 h. At the end of experiments, cells were harvested for total RNA and protein extraction.

(Pro)renin receptor siRNA transfection

Cells were either transfected with a scrambled siRNA (QIA-GEN, Valencia, California, USA, target sequences: 5′-AATTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′), which was confirmed as nonsilencing double-stranded RNA, and used as control for siRNA experiments or Accell PRR siRNA – SMART pool (20 μmol/l; Thermo Scientific Dharmacon Research Inc, USA, target sequences: 5′-CGAAUAGAUUGAAUUUUCC-3′; 5′-CGGUAUACCUUAAGUUUAU-3′; 5′-UGGUUUAGUAGAGAUAUUA-3′; 5′-GGACCAUCCUUGAGGCAAA). After 6 h of incubation in transfection reagent, the cells were then switched to normal salt with or without Ang II or low-salt medium for recovery [21–22].

RT-PCR analysis

mRNA expressions of PRR, SGK-1, and α-ENaC were performed as described in supplement methods section, http://links.lww.com/HJH/A566.

Western blot

Antibodies to PRR (1 : 1000 dilutions, Abcam, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA), prorenin/renin (1 : 200 dilutions; Santa Cruz biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, California, USA), SGK-1 (1 : 1000 dilutions, Cell Signaling, USA), p-Nedd4–2 (1 : 1000 dilutions, Abcam, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA), α-ENaC (1 : 500 dilutions; ASC-030, Alomone Labs, Israel) were used in the Western blot as previously described [12,21]. Protein expressions were normalized to β-actin protein.

Renal (Pro)renin receptor and epithelial sodium channel immunostaining

Kidney tissue blocks were prepared, deparaffinized, and sectioned as described previously [12]. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody directed against PRR monoclonal antibody (1 : 100 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA), or α-ENaC (1 : 50 dilutions; Alamone Labs, Israel). On the following day, sections were incubated for 1 h with secondary antibody at room temperature. A negative control (IgG) was included by omitting the primary antibody. The immunostaining images were captured by light microscopy using a Qimaging Micropublisher 5.0 RTV camera coupled to a Zeiss Axiophot microscopy (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Comparisons among different treatment groups were assessed by Student t-test, when appropriate or by one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey test for posthoc comparisons. Data are expressed as mean ± SE. P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Dose response

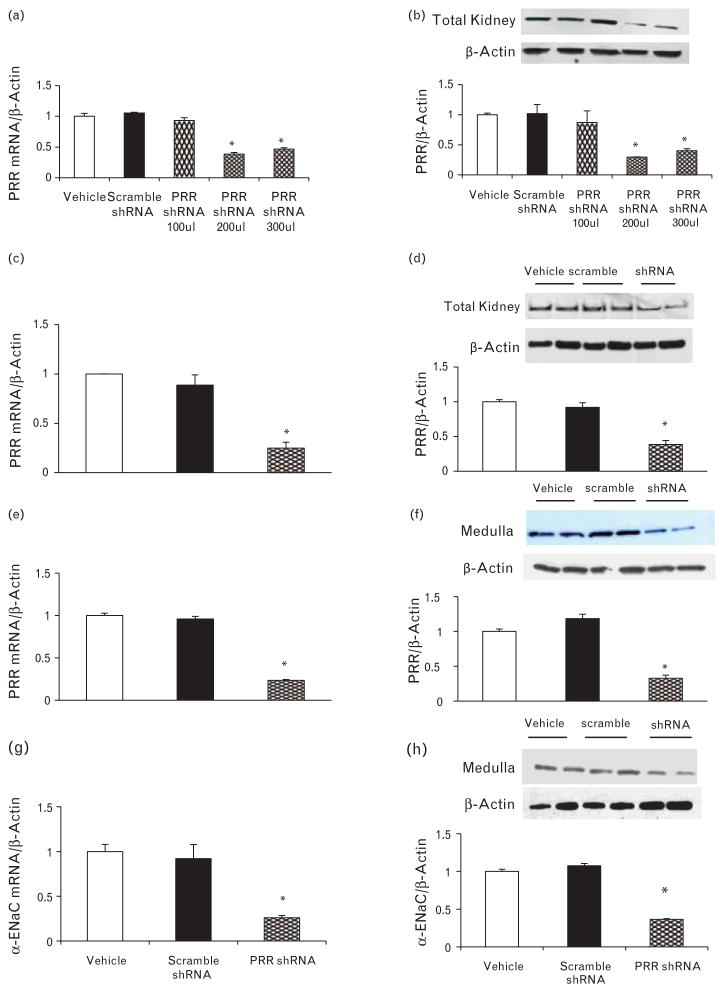

There were no significant differences in the total renal expression of PRR between vehicle, scramble shRNA, or PRR shRNA (100 μl) treatments groups. PRR shRNA (200 μl) treatment significantly reduced total renal expression of PRR mRNA and protein by 62 and 70%, respectively (P < 0.01). PRR shRNA (300 μl) reduced the expression of PRR mRNA and protein by 56 and 60%, respectively (P < 0.01, Fig. 1a and b). There was no significant difference in PRR expressions between 200 and 300 μl PRR shRNA.

FIGURE 1.

Expression of (Pro)renin receptor (PRR) in the kidney. PRR mRNA (a) and protein expression (b) in response to different doses of PRR shRNA. PRR mRNA and protein expression in total kidney tissue (c and d), renal medulla (e and f), and renal medulla α-ENaC mRNA and protein expression (f and g), respectively, at the end of the study in rats treated with vehicle (open bars), scramble shRNA (solid bars), or PRR shRNA (diamond bars). mRNA and protein levels were normalized to β-actin. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle or scramble shRNA.

Blood pressure, renal blood flow, glomerular filtration rate, urinary volume, urinary sodium volume and urinary potassium volume

There were no significant differences in systolic BP (Day 0: Vehicle 104 ± 1.34, scramble shRNA 104.2 ± 1.62, PRR shRNA 107 ± 1.28 mmHg; day 7 Vehicle: 101.6 ± 0.6, scramble shRNA 107.8 ± 1.51, PRR shRNA 108 ± 1.23 mmHg), diastolic BP (Day 0: Vehicle 67.8 ± 0.94, scramble shRNA 73.2 ± 1.52, PRR shRNA 73.1 ± 1.45 mmHg, day 7: Vehicle 68.8 ± 0.67, scramble shRNA 74.8 ± 0.55, PRR shRNA 75.6 ± 1.03 mmHg), renal cortical blood flow (Vehicle 36.4 ± 1.43, scramble shRNA 38.9 ± 0.6, PRR shRNA 38.9 ± 0.56 ml/min/100 g), renal medullary blood flow (Vehicle 25.8 ± 0.5, scramble shRNA 25.2 ± 0.3, PRR shRNA 23.7 ± 0.2 ml/min/100 g), GFR (Vehicle 0.98.4 ± 0.05, scramble shRNA 0.97 ± 0.13, PRR shRNA 1.12 ± 0.18 ml/min/g), urinary volume (Day 0: Vehicle 17 ± 1.78, scramble shRNA 17.3 ± 1.11, PRR shRNA 17 ± 0.37 ml/24 h; day 7: Vehicle 16.8 ± 1.23, scramble shRNA 17.5 ± 1.29, PRR shRNA 18.2 ± 1.19 ml/24 h) or urinary potassium volume (Day 0: Vehicle 0.13 ± 0.03, scramble shRNA 0.138 ± 0.04, PRR shRNA 0.125 ± 0.06 μmol/min; day 7: Vehicle 0.103 ± 0.02, scramble shRNA 0.12 ± 0.02, PRR shRNA 0.11 ± 0.03 μmol/min) between different treatment groups at baseline or at the end of the study. There were no differences in UNaV levels at baseline (Vehicle 214 ± 20.5, scramble shRNA 225 ± 21.4, PRR shRNA 227 ± 28.5 μmol/24 h). UNaV increased significantly at the end of study only in rats treated with PRR shRNA (Vehicle 220 ± 16.9, scramble shRNA 252 ± 21.6, PRR shRNA 357 ± 14.8 μmol/24 h; P < 0.05).

Expression of (Pro)renin receptor and α-epithelial sodium channel

There were no significant differences in expressions of PRR or α-ENaC subunit between vehicle or scramble shRNA treatments groups. PRR shRNA (200 μl) treatment significantly reduced total renal expression of PRR mRNA and protein by 76 and 62%, respectively (P < 0.01, Fig. 1c and d). Similarly, it significantly reduced PRR mRNA and protein expressions in the renal medulla by 77 and 68%, respectively (P < 0.01, Fig. 1e and f). PRR shRNA treatment significantly decreased mRNA and protein expressions of α-ENaC subunits in the renal medulla by 74 and 64%, respectively (P < 0.05, Fig. 1g and h).

Expressions of cardiac (Pro)renin receptor, and renal prorenin and renin

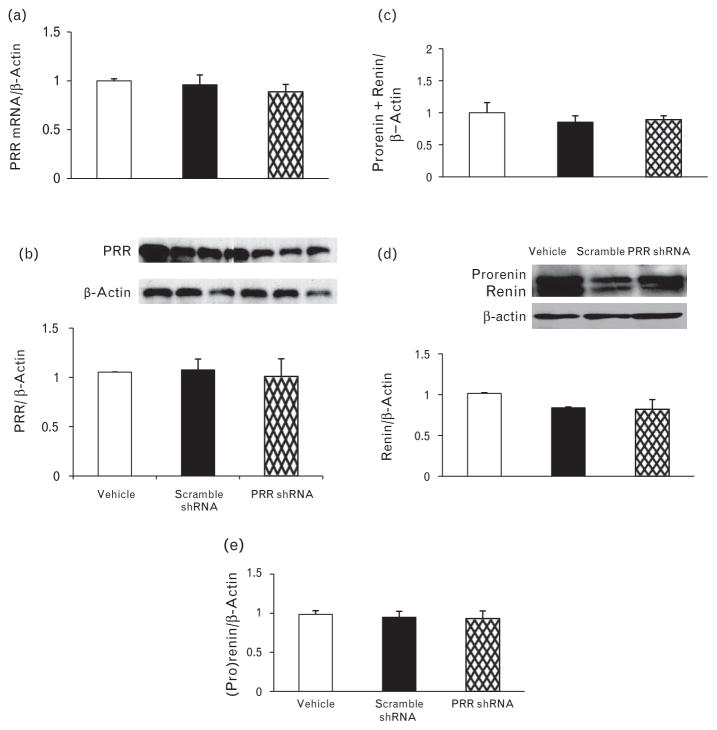

There were no significant changes in cardiac expression of PRR mRNA and protein (Fig. 2a and b) in response to left renal administration of different treatments.

FIGURE 2.

mRNA and protein expression of (Pro)renin receptor in heart (a and b), prorenin and renin mRNA (c), and protein expression (d and e) in total kidney at the end of the study in the rats given vehicle (open bars), scramble shRNA (solid bars), (Pro)renin receptor shRNA (diamond bars). mRNA and protein levels were normalized to β-actin.

We evaluated whether RAS is involved in the regulation of PRR expression as a result of its in-vivo knockdown with shRNA. There were no significant changes in mRNA and protein expressions of renin and prorenin (Fig. 2c and e) in response to different treatments.

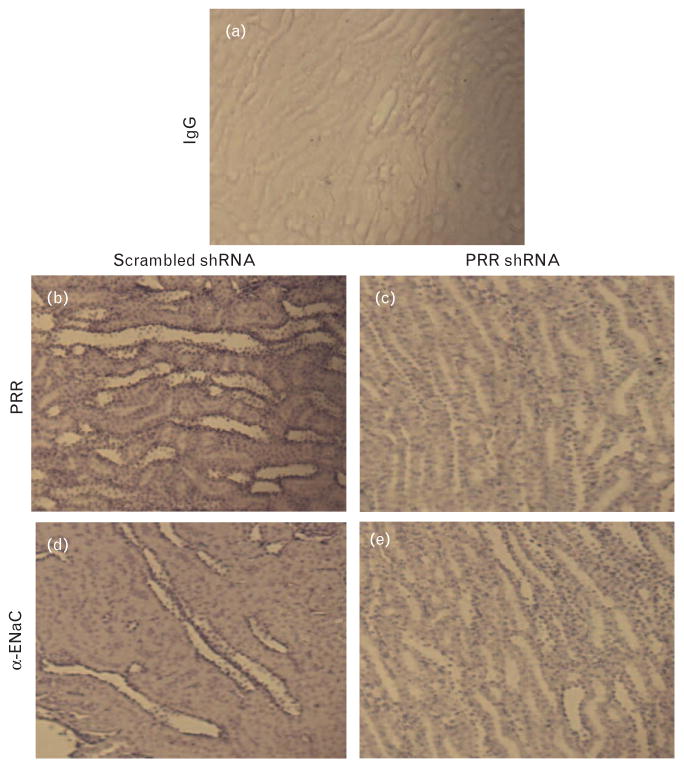

Immunostaining for (Pro)renin receptor and epithelial sodium channel in cortex and medulla

Compared with scramble shRNA, rats treated with PRR shRNA (200 μl) demonstrated a decrease in the renal PRR immunostaining in distal tubule (Fig. 3b and c). PRR shRNA treatment caused significant decrease in the immunostaining of α-ENaC in the distal tubule (Fig. 3d and e).

FIGURE 3.

Representative images of (Pro)renin receptor (b and c) and α-epithelial sodium channel (d and e) immunostaining in renal medulla. Left column represents scramble shRNA and right column represents (Pro)renin receptor shRNA.

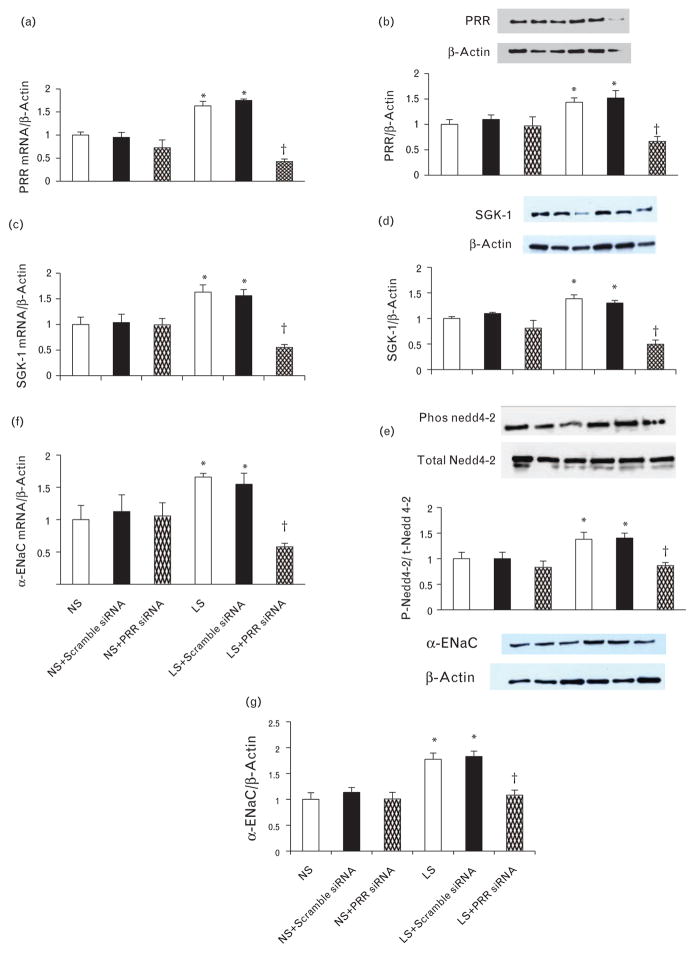

(Pro)renin receptor expression in mouse inner medullary collecting duct cells

Under normal salt condition, there were no changes in PRR mRNA and protein expressions in response to treatment with scramble or PRR siRNA. Compared with normal salt, low salt significantly increased PRR mRNA and protein expression by 63 and 43%, respectively (P < 0.05). In low salt group, treatment with PRR siRNA significantly reduced the PRR mRNA and protein expression by 74 and 53%, respectively (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4a and b). Similarly, compared to normal salt, treatment with Ang II significantly increased PRR mRNA and protein expression by 78 and 79%, respectively (P < 0.05). In Ang II group, treatment with PRR siRNA significantly reduced the PRR mRNA and protein expression by 60 and 51%, respectively (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5a and b).

FIGURE 4.

Expression of PRR, serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase isoform 1, p-neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally downregulated 4–2, and α-epithelial sodium channel in mIMCD and effect of PRR siRNA. PRR mRNA and protein expression (a and b), serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase isoform 1 mRNA and protein expression (c and d), phosphorylation of neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally downregulated 4–2 (e), α-epithelial sodium channel mRNA and (f and g) protein expression in response to normal salt and low salt. mRNA and protein levels were normalized to β-actin. PRR, (Pro)renin receptor.*P < 0.05 compared to normal salt and +P < 0.05 compared to low salt.

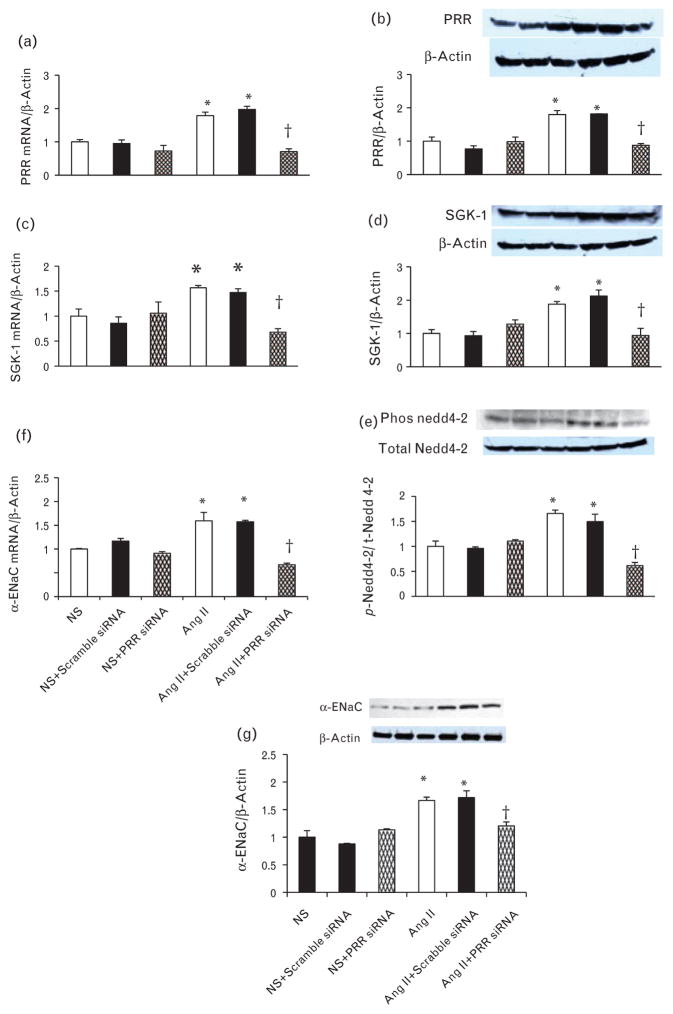

FIGURE 5.

Expression of PRR, serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase isoform 1, p-neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally downregulated 4–2 and α-epithelial sodium channel in mIMCD treated with Ang II and effect of PRR siRNA. PRR mRNA and protein expression (a and b), serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase isoform 1 mRNA, and protein expression (c and d), Phosphorylation of neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally downregulated 4–2 (e), α-epithelial sodium channel mRNA and (f and g) protein expression in response to normal salt and Angiotensin II. mRNA and protein levels were normalized to β-actin. PRR, (Pro)renin receptor. *P < 0.05 compared to normal salt and +P < 0.05 compared to Ang II.

Serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase isoform 1 expression in mouse inner medullary collecting duct cells

Under normal salt condition, there were no changes in SGK-1 mRNA and protein expression in response to treatment with scramble or PRR siRNA. Exposure to low salt significantly increased SGK-1 mRNA and protein expression by 63 and 38%, respectively (P < 0.05). Treatment with combined low salt and PRR siRNA significantly reduced SGK-1 mRNA and protein expression by 66 and 64%, respectively (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4c and d). Compared to normal salt, treatment with Ang II significantly increased SGK-1 mRNA and protein expression by 56 and 87%, respectively (P < 0.05). Treatment with combined Ang II and PRR siRNA significantly reduced the PRR mRNA and protein expression by 57 and 50%, respectively (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5c and d).

Phosphorylation of neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally downregulated 4–2

Under normal salt condition, there were no significant changes in p-Nedd 4–2 in response to treatment with scramble or PRR siRNA. Low salt increased p-Nedd4–2 by 37% (P < 0.05). Treatment with combined low salt and PRR siRNA significantly reduced the p-Nedd4–2 by 38% (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4e). Compared to normal salt, Ang II increased p-Nedd4–2 by 65% (P < 0.05). Treatment with combined Ang II and PRR siRNA significantly reduced the p-Nedd4–2 by 63% (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5e).

Expression of α-epithelial sodium channel in mouse inner medullary collecting duct cells

Under normal salt condition, there were no changes in mRNA and protein expressions of α-ENaC in response to treatment with scramble or PRR siRNA. Compared with normal salt, low salt increased α-ENaC mRNA and protein expression by 65 and 57%, respectively (P < 0.05). Combined low salt and PRR siRNA treatment significantly reduced α–ENaC mRNA and protein expressions of by 64 and 31%, respectively (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4f and g). Similarly, treatment with Ang II significantly increased α-ENaC mRNA and protein expression by 59 and 66%, respectively (P < 0.05). In Ang II group, treatment with PRR siRNA significantly reduced the PRR mRNA and protein expression by 58 and 30%, respectively (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5f and g).

DISCUSSION

The present study was conducted to evaluate the role of PRR in regulation of renal α-ENaC. We hypothesized that PRR regulates renal α-ENaC expression via SGK-1-Nedd4–2 signaling pathway. Our in-vivo results demonstrated that knockdown of PRR in the kidney reduced the expression of α-ENaC in the distal tubules without any changes in renal hemodynamic function.

Recently, we demonstrated an increase in renal PRR expression in response to low sodium [12–13] and established that the cGMP-PKG signaling pathway regulates its expression under such condition by enhancing the binding of CREB-1, NF-κB p65, and c-Jun to PRR promoter. However, the physiological role of PRR in the kidney is still not well elucidated. In the kidney, PRR is predominantly expressed in glomeruli [12], distal tubules, and collecting ducts [23]. Our in-vivo study was designed to evaluate the effects of decreased renal PRR on α-ENaC expression after 1 week of PRR shRNA treatment. Interestingly, studies using conditional PRR knockout in podocytes resulted in significant albuminuria and animal’s death within few weeks [24–25], demonstrating the importance of this receptor during development. In our study, we did not observe increase mortality in animals treated with PRR shRNA. The short duration of our study, 1 week, and relative reduction of PRR expression (about 70%) in adult fully developed kidney may explain the survival difference between our study and previous reports [25,26]. In the present study, we confirmed the dose and efficiency of PRR shRNA transfection by quantitative RT-PCR and western blot analysis [26–27]. We also confirmed that PRR shRNA treatment was confined to the kidney as evidenced by the absence of changes in PRR expression in a distant organ, the heart.

The current study demonstrates a novel finding that PRR contributes to the regulation of renal α-ENaC expression. Previous studies showed that renin angiotensin system enhance the expression of ENaC [28–29]. For instance, Peti-Peterdi et al. [29], found that Ang II increased luminal sodium transport and this effect was attenuated by AT1 receptor antagonist losartan, indicating direct regulation of ENaC by Ang II. Similar observation was reported in collecting ducts where Ang II increased ENaC expression and activity [30]. Our data corroborate with the previous reports and demonstrates that Ang II treatment significantly increased α-ENaC expression in mIMCD cells. However, the current in-vivo study was conducted during normal sodium intake, thus eliminating any significant contributions of the RAS to ENaC expression. In the present study, we did not observe changes in renal renin or prorenin with any of administered treatments, and makes it unlikely that RAS in general or Ang II in particular, contributed to PRR shRNA effects. The observed decrease in renal distal tubule α-ENaC subunit expression induced by downregulation of PRR provides a direct evidence for functional role of this receptor in the kidney.

Interestingly, despite an increase in the urinary sodium excretion because of a decrease in the α-ENaC expression in response to renal downregulation of PRR, we did not observe any significant changes in blood pressure. This is unexpected finding and could be because of the short duration of the study, free access to food and water or other vasoactive compensatory mechanisms. However, we cannot completely rule out a role for PRR in BP regulation. The absence of changes in the RBF and GFR, and increased UNaV with the reduction of PRR expression indicates that the observed natriuresis is attributed to reduced tubular sodium transport and not because of change in renal hemodynamic function. Our in-vitro study was designed to investigate the role of SGK-1-Nedd4–2 signaling pathway in mediating the effects of PRR on regulation of α-ENaC expression in the kidney. For this purpose, we selected mouse inner medullary collecting duct cells, which express both α-ENaC [31] and PRR [13]. Recently, Wang et al. [32], demonstrated that PRR is expressed in primary rat IMCD and indicated that Ang II upregulates PRR expression. Similarly, Ang II has been shown to upregulate SGK-1 and ENaC expression [28,33]. In the present study, experiments were conducted in vitro in mIMCD cells with or without any treatment with exogenous Ang II, suggesting presence of a RAS-dependent and independent regulation of PRR, SGK-1, and ENaC expression. These results complement our previous data demonstrating that PRR expression is upregulated in cells exposed to low salt or Ang II [21]. Our second finding is that increased PRR contributed to the increment in the SGK-1 expression. Previous studies reported that SGK-1 inhibited channel retrieval and increased the surface expression of α-ENaC. In addition, SGK1 was reported to stimulate ENaC by phosphorylating Nedd4–2, thereby preventing Nedd4–2-dependent channel ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [34]. Our data confirmed the previous findings and demonstrated that an increase in SGK-1 enhances the α-ENaC expression by phosphorylating Nedd4–2. The increase in SGK-1 and α-ENaC was attenuated by PRR siRNA treatment.

We conclude that renal PRR regulates α-ENaC via SGK-1-Nedd4–2 signaling pathway. These findings may lead to better understanding of the physiologic role of the PRR in the kidney. Future studies would look into prorenin/renin stimulation of PRR on α-ENaC expression.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK078757 and HL091535 to H.M.S.

Abbreviations

- Ang

angiopoietin

- BP

blood pressure

- ENaC

epithelial sodium channel

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- Nedd4-2

neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally down-regulated 4–2

- PRR

(pro)renin receptor

- RAS

renin-angiotensin system

- SGK-1

serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase isoform 1

- UNaV

urinary sodium volume

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Li W, Peng H, Seth DM, Feng Y. The prorenin and (Pro)renin receptor: new players in the brain renin: angiotensin System? Int J Hypertens. 2012;2012:290635. doi: 10.1155/2012/290635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang J, Siragy HM. Regulation of (pro)renin receptor expression by glucose-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase, nuclear factor-kappaB, and activator protein-1 signaling pathways. Endocrinology. 2010;151:3317–3325. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shehata MF. The Epithelial Sodium Channel alpha subunit (alpha ENaC) alternatively spliced form ‘b’ in Dahl rats: What’s next? Int Arch Med. 2010;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1755-7682-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canessa CM, Schild L, Buell G, Thorens B, Gautschi I, Horisberger JD, et al. Amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channel is made of three homologous subunits. Nature. 1994;367:463–467. doi: 10.1038/367463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duc C, Farman N, Canessa CM, Bonvalet JP, Rossier BC. Cell-specific expression of epithelial sodium channel alpha, beta, and gamma subunits in aldosterone-responsive epithelia from the rat: localization by in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry. J Cell Biol. 1994;127(6 Pt 2):1907–1921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvarez de la Rosa D, Canessa CM, Fyfe GK, Zhang P. Structure and regulation of amiloride-sensitive sodium channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2000;62:573–594. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ergonul Z, Frindt G, Palmer LG. Regulation of maturation and processing of ENaC subunits in the rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F683–F693. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00422.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu M, Wang J, Jones KT, Ives HE, Feldman ME, Yao LJ, et al. mTOR complex-2 activates ENaC by phosphorylating SGK1. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:811–818. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009111168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen SY, Bhargava A, Mastroberardino L, Meijer OC, Wang J, Buse P, et al. Epithelial sodium channel regulated by aldosterone-induced protein sgk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2514–2519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naray-Fejes-Toth A, Canessa C, Cleaveland ES, Aldrich G, Fejes-Toth G. sgk is an aldosterone-induced kinase in the renal collecting duct. Effects on epithelial na+ channels. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16973–16978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang LM, Rinke R, Korbmacher C. Stimulation of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) by cAMP involves putative ERK phosphorylation sites in the C termini of the channel’s beta- and gamma-subunit. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9859–9868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512046200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matavelli LC, Huang J, Siragy HM. In vivo regulation of renal expression of (pro)renin receptor by a low-sodium diet. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;303:F1652–F1657. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00204.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang J, Siragy HM. Sodium depletion enhances renal expression of (pro)renin receptor via cyclic GMP-protein kinase G signaling pathway. Hypertension. 2012;59:317–323. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.186056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed F, Kemp BA, Howell NL, Siragy HM, Carey RM. Extracellular renal guanosine cyclic 3′5′-monophosphate modulates nitric oxide and pressure-induced natriuresis. Hypertension. 2007;50:958–963. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.092973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quadri S, Prathipati P, Jackson D, Jackson K. Regulation of heme oxygenase-1 induction during recurrent insulin induced hypoglycemia. 2014;XXX doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siragy HM, Inagami T, Carey RM. NO and cGMP mediate angiotensin AT2 receptor-induced renal renin inhibition in young rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R1461–R1467. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00014.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson KE, Jackson DW, Quadri S, Reitzell MJ, Navar LG. Inhibition of heme oxygenase augments tubular sodium reabsorption. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300:F941–F946. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00024.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quadri S, Jackson DW, Prathipati P, Dean C, Jackson KE. Heme induction with delta-aminolevulinic Acid stimulates an increase in water and electrolyte excretion. Int J Hypertens. 2012;2012:690973. doi: 10.1155/2012/690973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quadri S, Prathipati P, Jackson DW, Jackson KE. Haemodynamic consequences of recurrent insulin-induced hypoglycaemia. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;41:81–88. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang T, Park JM, Arend L, Huang Y, Topaloglu R, Pasumarthy A, et al. Low chloride stimulation of prostaglandin E2 release and cyclooxygenase-2 expression in a mouse macula densa cell line. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37922–37929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quadri S, Siragy HM. Regulation of (pro)renin receptor expression in mimcd via GSK3beta-NFAT5- SIRT-1 signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00245.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li C, Siragy HM. High glucose induces podocyte injury via enhanced (pro)renin receptor-Wnt-beta-catenin-snail signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Advani A, Kelly DJ, Cox AJ, White KE, Advani SL, Thai K, et al. The (Pro)renin receptor: site-specific and functional linkage to the vacuolar H+-ATPase in the kidney. Hypertension. 2009;54:261–269. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.128645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oshima Y, Kinouchi K, Ichihara A, Sakoda M, Kurauchi-Mito A, Bokuda K, et al. Prorenin receptor is essential for normal podocyte structure and function. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:2203–2212. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011020202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riediger F, Quack I, Qadri F, Hartleben B, Park JK, Potthoff SA, et al. Prorenin receptor is essential for podocyte autophagy and survival. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:2193–2202. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011020200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gou D, Narasaraju T, Chintagari NR, Jin N, Wang P, Liu L. Gene silencing in alveolar type II cells using cell-specific promoter in vitro and in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e134. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inagaki K, Fuess S, Storm TA, Gibson GA, McTiernan CF, Kay MA, et al. Robust systemic transduction with AAV9 vectors in mice: efficient global cardiac gene transfer superior to that of AAV8. Mol Ther. 2006;14:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mamenko M, Zaika O, Ilatovskaya DV, Staruschenko A, Pochynyuk O. Angiotensin II increases activity of the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) in distal nephron additively to aldosterone. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:660–671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.298919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peti-Peterdi J, Warnock DG, Bell PD. Angiotensin II directly stimulates ENaC activity in the cortical collecting duct via AT(1) receptors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1131–1135. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000013292.78621.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun P, Yue P, Wang WH. Angiotensin II stimulates epithelial sodium channels in the cortical collecting duct of the rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302:F679–F687. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00368.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gumz ML, Cheng KY, Lynch IJ, Stow LR, Greenlee MM, Cain BD, et al. Regulation of alphaENaC expression by the circadian clock protein Period 1 in mpkCCD(c14) cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:622–629. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang F, Lu X, Peng K, Zhou L, Li C, Wang W, et al. COX-2 Mediates Angiotensin II-Induced (Pro)Renin Receptor Expression in the Rat Renal Medulla. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00548.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevens VA, Saad S, Poronnik P, Fenton-Lee CA, Polhill TS, Pollock CA. The role of SGK-1 in angiotensin II-mediated sodium reabsorption in human proximal tubular cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:1834–1843. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diakov A, Korbmacher C. A novel pathway of epithelial sodium channel activation involves a serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase consensus motif in the C terminus of the channel’s alpha-subunit. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38134–38142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]