Abstract

Dominant mutations in keratin genes can cause a number of inheritable skin disorders characterized by intraepidermal blistering, epidermal hyperkeratosis, or abnormalities in skin appendages, such as nail plate dystrophy and structural defects in hair. Allele-specific silencing of mutant keratins through RNA interference is a promising therapeutic approach for suppressing the expression of mutant keratins and related phenotypes in the epidermis. However, its effectiveness on skin appendages remains to be confirmed in vivo. In this study, we developed allele specific siRNAs capable of selectively suppressing the expression of a mutant Krt75, which causes hair shaft structural defects characterized by the development of blebs along the hair shaft in mice. Hair regenerated from epidermal keratinocyte progenitor cells isolated from mutant Krt75 mouse models reproduced the blebbing phenotype when grafted in vivo. In contrast, mutant cells manipulated with a lentiviral vector expressing mutant Krt75-specific shRNA persistently suppressed this phenotype. The phenotypic correction was associated with significant reduction of mutant Krt75 mRNA in the skin grafts. Thus, data obtained from this study demonstrated the feasibility of utilizing RNA interference to achieve durable correction of hair structural phenotypes through allele-specific silencing of the mutant keratin genes.

Keywords: siRNA, hair follicle, keratin, gene therapy, regeneration, ex vivo

INTRODUCTION

Keratins are the most abundant form of intermediate filament proteins in keratinocytes. Mutations in keratins are responsible for the majority of inheritable epidermal disorders, such as epidermolysis bullosa (EBS), epidermolytic ichthyosis (EI, formerly known as epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EHK)), Ichthyosis bullosa of Siemens (IBS), and pachyonychia congenita (PC), which are characterized by intraepidermal blistering and generalized or palmoplantar hyperkeratosis (Lane and McLean, 2004; Uitto et al., 2007). Mutations in hair follicle related keratins can cause hair abnormalities, such as monilethrix, autosomal dominant woolly hair, and pseudofolliculitis barbae (Harel and Christiano, 2012; Schweizer et al., 2007).

Most disease-causing mutations in keratins are dominant-negative mutations, in which the mutant keratin gene products adversely affect the integrity of the keratin intermediate filament network of affected keratinocytes (Harel and Christiano, 2012; Knobel et al., 2015; McLean and Moore, 2011; Uitto et al., 2007). Suppressing the production of mutant keratins through allele-specific inhibition of mutant keratin genes may be effective in correcting associated phenotypes (Knobel et al., 2015; McLean and Moore, 2011).

RNA interference (RNAi) has been successfully utilized in achieving allele-specific inhibition of mutant keratin genes. For example, mutant-specific siRNAs against disease-causing mutations in the KRT9, KRT5, and KRT6A genes were demonstrated to be capable of inhibiting the expression of these mutant keratins in vitro and in vivo (Atkinson et al., 2011; Hickerson et al., 2011b; Hickerson et al., 2008; Leslie Pedrioli et al., 2012). Moreover, intraepidermal injection of siRNA was capable of suppressing plantar hyperkeratosis in pachyonychia congenita (Leachman et al., 2010), confirming the therapeutic value of this approach for correcting phenotypes associated with keratin mutations. Whether this strategy can achieve lasting therapeutic benefit is yet to be determined in vivo.

KRT75, formerly known as K6HF, is expressed in the companion layer of the hair follicle and the medulla of the hair shaft (Winter et al., 1998; Wojcik et al., 2001). Heterozygous mutations in KRT75 (A12T and E337K) are associated with the development of pseudofolliculitis barbae and loose anagen hair syndrome, respectively (Chapalain et al., 2002; Winter et al., 2004). Moreover, decreased expression of KRT75 was also observed in cicatricial alopecia (Chapalain et al., 2002; Sperling et al., 2010). Genetically engineered mutant mice (Krt75tm1Der) expressing a mutant form of Krt75 (N159del) developed hair shaft blebbing (Chen et al., 2008). Moreover, mutations in Krt75 also contribute to the development of frizzle feathers in chicken (Ng et al., 2012) and altered enamel structure of human teeth (Duverger et al., 2014). These observations demonstrated an important role of KRT75 in maintaining the structural integrity of the hair and other skin appendages.

In this study, we demonstrated that hair follicles regenerated with mutant Krt75 epidermal keratinocyte progenitor cells were able to reproduce the hair shaft blebbing phenotype in vivo. Suppressing mutant Krt75 expression by shRNA effectively suppressed the development of this hair shaft phenotype. Thus, this study established the feasibility of using ex vivo modified epidermal keratinocyte progenitor cells to prevent structural abnormalities of the hair.

RESULTS

Development of allele-specific siRNA for mutant Krt75

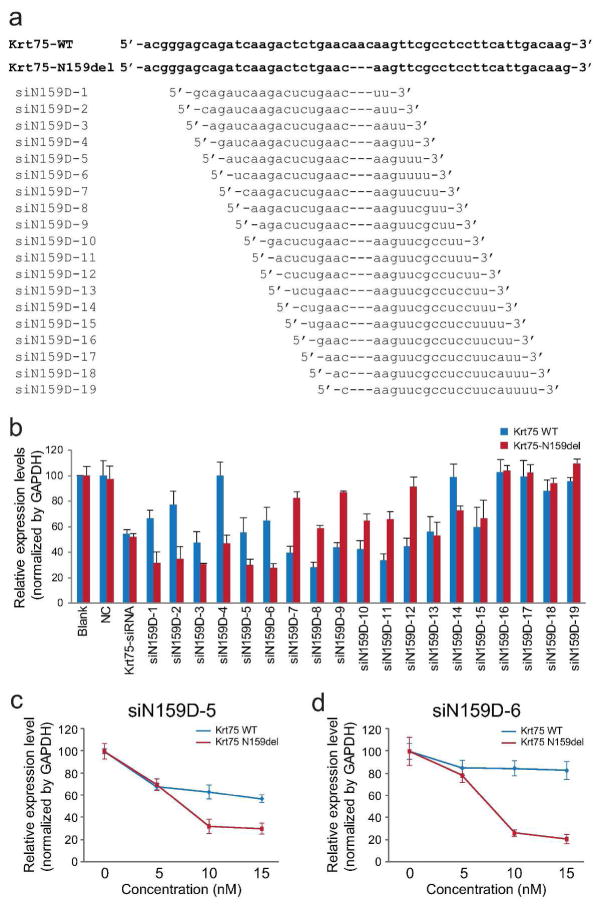

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are capable of selectively silencing mutant keratin genes, such as KRT6A, KRT5, and KRT9, at the resolution of single base pairs. In this study, we examined whether siRNA is able to suppress a three base pair in-frame deletion (c.545_547del (p.N159del)) mutation in the mouse Krt75 gene (Chen et al., 2008). Nineteen candidate siRNAs for the mutant Krt75 were engineered and tested by allele-specific qRT-PCR (Figure 1a and Supplemental Figure S1).

Figure 1. Mutant Krt75-specific siRNA.

(a) Sequences of wild-type and c.545_547del (p.N159del) Krt75 and candidate siRNAs for mutant Krt75. (b) Relative expression levels of wild-type and mutant Krt75 in HEK293T cells co-transfected with wild-type and mutant Krt75 and siRNA (15 nM) by quantitative RT-PCR. Blank, cells transfected with Krt75 expression plasmids without siRNA; NC, cells transfected with negative control (a fragment of inverted beta-galactosidase sequence) siRNA; Krt75-siRNA, a commercially available siRNA against Krt75. (c, d) Relative expression levels of wild-type and mutant Krt75 in cells transfected with 0 − 15 nM siN159D-5 and siN159D-6 siRNAs, as normalized to GAPDH. All experiments were carried out in triplicates in a minimum of three independent experiments.

Two candidate siRNAs, siN159D-5 and siN159D-6 (15 nM), demonstrated strong (> 70%) inhibition of mutant Krt75, but a moderate (< 45%) effect on wild-type Krt75 (Figure 1b). In contrast, negative control siRNA (15 nM) had no effect on the expression of Krt75 and a positive control siRNA (15 nM) indiscriminately suppressed the expression of both wild-type and mutant Krt75 (Figure 1b). When evaluated at variable concentrations, both siN159D-5 and siN159D-6 demonstrated robust inhibitory effect on mutant Krt75 (Figure 1c and d), but siN159D-6 is more selective for mutant, but not wild-type Krt75 (Figure 1d). Thus, siN159D-6 was selected for future experiments. The scrambled sequence of siN159D-6 was used as negative control (siN159D-6S).

In order to achieve long-term inhibition in cells in vivo, siN159D-6 and siN159D-6S were cloned as hairpin shRNAs into pLVX-ShRNA2 lentiviral vectors (Supplemental Figure S2). Lentiviral vectors are not only able to efficiently infect large amounts of keratinocyte progenitor cells, but are also able to integrate into the cell’s genome, thereby achieving continuous expression of shRNA. Lentiviral vectors expressing shN159D-6 or shN159D-6S were able to efficiently infect HEK293T and primary keratinocytes (greater than 83.6% and 82.0%, respectively) without noticeable adverse effects on cell growth and morphology in vitro (Supplemental Figure S2).

Mutant Krt75-specific shRNA suppresses hair shaft phenotype

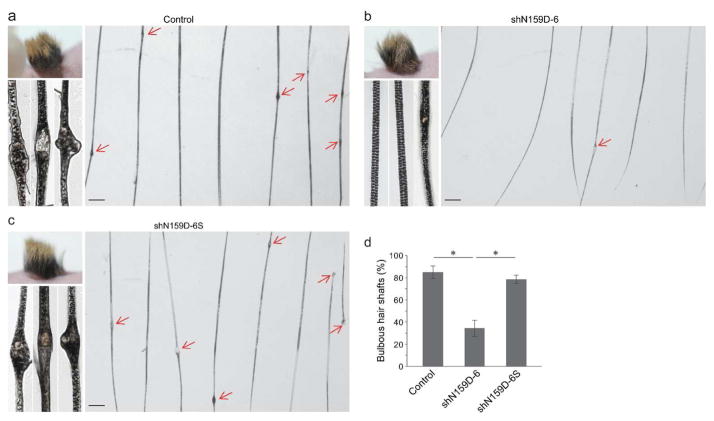

To establish an in vivo model suitable for testing therapeutic effectiveness of RNAi, mutant Krt75 keratinocyte progenitor cells were isolated from homozygous mutant Krt75 mice (Krt75tm1Der/Krt75tm1Der) and grafted onto immune deficient nude mice to regenerate skin and hair follicles in vivo. Mutant cells efficiently regenerated skin and hair and, most importantly, the majority of hair shafts (85.2 ± 5.4%) contained the characteristic bleb phenotype as observed in the homozygous mutant Krt75 mice (Figure 2a and Supplemental Figure S3). This result demonstrated the grafting of ex vivo cultured mutant keratinocyte progenitor cells can be used as a model to test therapeutic intervention.

Figure 2. Phenotypes of hair regenerated with shRNA-modified homozygous mutant Krt75 keratinocyte progenitor cells.

(a–c) Representative gross appearance, low and high power images of hair regenerated with non-infected cells. Control (a), shN159D-6 lentiviral vector infected cells (b), and scrambled (shN159D-6S) lentiviral vector infected cells (c) at one month of grafting. Arrows point to bulbous lesions (blebs) along the hair shaft. (d) Quantification of hair shafts containing blebs. Asterisk, P < 0.05. Scale bar: 250 μm.

To determine whether mutant Krt75-specific shRNA was able to suppress hair shaft defects regenerated in skin grafts, homozygous mutant Krt75 keratinocytes were infected with lentiviral vectors prior to grafting. One month later, hair was regenerated. Analyses of hair regenerated with lentiviral vector-infected cells by light and transmission electron microscopy demonstrated that shN159D-6 was able to robustly suppress the formation of blebs in the hair shaft such that only 34.6 ± 7.6% of hair shafts contained bulbous lesions (Figure 2b and d, and Supplemental Figure S3). In contrast, scrambled shRNA (shN159D-6S) had no effect on suppressing the hair phenotype (Figure 2c and d, and Supplemental Figure S3) and the majority (78.6 ± 4.0%) of hair shafts regenerated with scrambled shRNA-treated cells contained defective hair shafts (Figure 2d).

Because some hairs contain more than one bleb, the effectiveness of shRNA was also evaluated based on the number of bulbous lesions per hair shaft. Affected hair shafts regenerated with shN159D-6 lentiviral vector-infected cells contained 0.97 ± 0.11 bulbous lesions (Supplemental Figure S4), whereas affected hair shafts regenerated with non-infected cells and scrambled (shN159D-6S) lentiviral vector infected cells contained 1.43 ± 0.28 and 1.44 ± 0.23 blebs per hair shaft one month after grafting, respectively (P < 0.01, Supplemental Figure S4). Collectively, these findings demonstrated that the mutant Krt75-specific shRNA was not only able to suppress the frequency of defective hair shafts, but also ameliorate the severity of affected hair.

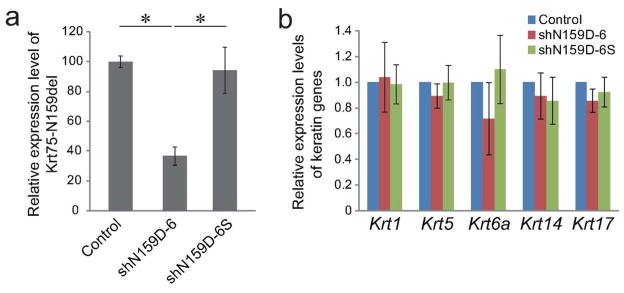

Mutant-specific shRNA suppresses the expression of mutant Krt75 in vivo

To determine whether suppression of the hair phenotype was associated with suppression of mutant Krt75 expression, qRT-PCR was performed on skin grafts. The relative expression level of mutant Krt75 was normalized to its level in non-infected control grafts. A marked reduction in the level of mutant Krt75 transcripts (37.3 ± 6.9%) was observed in grafts regenerated with shN159D-6 lentiviral vector-infected cells (Figure 3a). In comparison, the expression level of mutant Krt75 (94.2 ± 11.6%) in grafts regenerated with scrambled shRNA was almost identical to that in controls (Figure 3a).

Figure 3. Gene expression in skin grafts regenerated with shRNA modified homozygous mutant Krt75 keratinocyte progenitor cells.

(a) Relative expression level of mutant Krt75 (Krt75-N159del) in grafts regenerated with ex vivo cultured cells (as described in Figure 2) by qRT-PCR one month after grafting . (b) Relative expression levels of Krt1, Krt5, Krt6a, Krt14, and Krt17 by qRT-PCR in skin grafts described in (a). All experiments were carried out in triplicates in a minimum of three independent experiments. Asterisk, P < 0.05.

The expression of a number of keratin genes that are expressed in the epidermis and hair follicles (Krt5, Krt14, and Krt1) or related to Krt75 (Krt6a and Krt17) was evaluated. Results showed that the expression profiles of these genes were not affected in skin grafts regenerated with lentiviral vectors expressing either mutant Krt75-specific shRNA or scrambled shRNA. These results suggest that lentiviral-mediated transcription suppression of a mutant form of keratin is likely capable of achieving high specificity in vivo.

Lentiviral-mediated ex vivo modification of keratinocyte progenitor cells exhibit a sustained suppression of phenotype

To further determine whether phenotypic suppression was sustainable, skin grafts were analyzed three months after grafting. We estimate that hair follicles analyzed three months after grafting underwent two more hair cycles than those harvested at one month post-grafting. First, all experimental groups displayed no evidence of hair loss at three months (Supplemental Figure S5). Examination of hair shafts revealed that the proportion of phenotypic hair shafts in control and shRNA-treated groups was consistent with those harvested at one month post-grafting (Supplemental Figure S5). Specifically, non-infected control and scrambled shRNA-infected keratinocytes regenerated hair shafts with 84.7 ± 3.1% and 81.2 ± 5.3% defects, respectively (Supplemental Figure S5). In contrast, hair regenerated with cells infected with shN159D-6 contained 37.0 ± 9.0% defective hair shafts (Supplemental Figure S5). Thus, hair regenerated with shN159D-6 treated cells harbored significantly reduced numbers of defective shafts (P < 0.05, Supplemental Figure S5). These results suggested that lentiviral vector-mediated manipulation of ex vivo cultured keratinocytes was able to maintain a lasting suppression of hair shaft phenotypes, likely due to the integration capability of lentiviral vectors and continuous expression of encoded shRNA.

RNAi can suppress phenotypes associated with heterozygous mutant Krt75

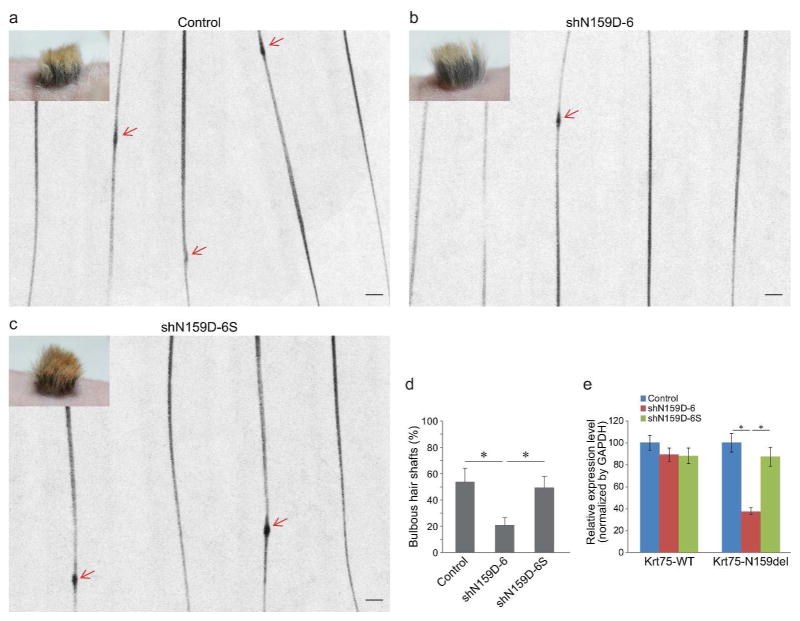

So far, the therapeutic effect of shN159D-6 was examined in homozygous mutant Krt75 cells. However, disease-causing mutations in keratin genes are predominantly heterozygous mutations (Harel and Christiano, 2012; Lane and McLean, 2004; Uitto et al., 2007), including those in KRT75 (Chapalain et al., 2002; Winter et al., 1998). To determine whether the RNAi is capable of suppressing phenotypes associated with heterozygous mutations, hair was regenerated with epidermal keratinocyte progenitor cells obtained from heterozygous mutant Krt75 mice (Krt75+/Krt75tm1Der).

Hair regenerated with heterozygous mutant Krt75 cells contained 53.8 ± 10.4% bulbous hair shafts (Figure 4a and d). In contrast, hair regenerated with heterozygous mutant cells treated with shRNAD-6 contained only 20.9 ± 5.8% defective hair shafts, which was significantly reduced in comparison to non-infected and scrambled shRNA-treated (49.3 ± 8.9) groups (P < 0.05, Figure 4).

Figure 4. Phenotype and gene expression in skin grafts regenerated with shRNA-modified heterozygous mutant Krt75 keratinocyte progenitor cells.

(a–c) Representative hair phenotypes of hair regenerated with control and lentiviral vector-infected cells (as described in Figure 2) at one month of grafting. Arrows point to bulbous lesions (blebs) along the hair shaft. (d) Quantification of hair shafts containing blebs. (e) Relative expression level of wild-type (Krt75-WT) and mutant Krt75 (Krt75-N159Del) in skin grafts described in (a). Asterisk, P < 0.05. Scale bar: 250 μm.

Heterozygous mutant cells express both wild-type and mutant Krt75, permitting the evaluation of the transcriptional levels of both transcripts. Quantitative RT-PCR on wild-type Krt75 demonstrated comparable expression levels of wild-type Krt75 in all experimental groups (non-infected control, 100.0 ± 6.7; shN159D-6, 89.2 ± 6.1; shN159D-6S, 88.1 ± 7.0, Figure 4e). In contrast, the expression of mutant Krt75 was selectively suppressed in shRNAD-6 treated group (37.5 ± 3.3) but not in non-infected or scrambled controls (100.0 ± 8.4 and 87.4 ± 8.5, respectively, Figure 4e). These results suggest that suppressing the expression of mutant Krt75 in heterozygous mutant cells is able to ameliorate the blebbing phenotype of the hair.

DISCUSSION

RNAi-mediated ex vivo therapy is among the most promising approaches for correcting phenotypes associated with dominant mutations in keratin genes in skin (Uitto, 2012). Although keratins are redundantly expressed in keratinocytes and considerable homology exists among keratin genes, recent progress has demonstrated the feasibility of engineering allele-specific siRNAs that are capable of suppressing mutant keratin expression (Atkinson et al., 2011; Hickerson et al., 2008; Leslie Pedrioli et al., 2012). More importantly, evidence obtained from a number of in vitro and in vivo models, and a single patient, split-body, vehicle-controlled phase I clinical trial support the usefulness of utilizing siRNA to suppress mutant keratin expression (Hickerson et al., 2011a; Leachman et al., 2010; Leslie Pedrioli et al., 2012). In this study, we developed siRNAs capable of specifically inhibiting a dominant mutant form of Krt75, and confirmed the effectiveness of RNAi-based ex vivo therapy at both the phenotypic and molecular levels in mice. Data obtained from this study not only demonstrated the feasibility of permanently suppressing the expression of mutant keratins, but also provided an example of correcting structural hair defects with ex vivo modified epidermal keratinocyte progenitor cells in vivo.

Models capable of mimicking skin disorders at both phenotypic and genetic levels may serve as important tools in testing novel therapeutics for inheritable skin disorders. The mouse model utilized in this study is a knock-in model. It contains a mutation analogous to one found in the KRT6A gene in pachyonychia congenita patients, in its endogenous Krt75 locus (Chen and Roop, 2008). This mouse model represents genetic changes that occur in most keratin mutation-related disorders. Therefore, it may serve as an ideal pre-clinical model in performing proof-of-principle experiments pertinent to the development of therapeutics for disorders caused by keratin mutations.

The mutation targeted in this study is an in-frame three base-pair deletion mutation. It is analogous to a common mutation in the KRT6A gene (c.513_515del (p.N171del), which is also reported as (c.516_518del (p.N172del) as the codon 171 and 172 are identical) in pachyonychia congenita (PC) patients (Smith et al., 2005; Wilson et al., 2014). Because sequences flanking this site are almost identical between the mouse Krt75 gene and human KRT6A gene, data obtained from this study strongly suggests that it is feasible to specifically target this mutation in human KRT6A. In fact, potent siRNAs were previously developed for a missense mutation (c.513C> A (p.N171K)) and the analogous c.513_515del mutation in KRT6A (Hickerson et al., 2011b; Hickerson et al., 2006). Interestingly, the most potent and selective siRNA for the analogous deletion in mouse Krt6a (N159del) or the human KRT6A (N171del) target the same region (D6 in Fig. 1c or (Hickerson et al., 2006), respectively). Thus, these findings collectively support the rationale of using RNAi to suppress the disease-causing mutant allele.

Mutations in a number of genes involved in inheritable hair disorders cause structural defects in the hair shaft (Harel and Christiano, 2012). Pertinent to this study, mutations in KRT75 are linked to loose anagen hair syndrome (Chapalain et al., 2002) and pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) (Winter et al., 2004). It is postulated that KRT75 is important for maintaining the integrity of the keratin intermediate filament network in companion layer cells where it is expressed. Mutations in KRT75 likely destabilize endogenous keratin filaments. When compounded by mechanical stress, such as combing and shaving, mutant KRT75 is likely to lead to the development of hair phenotypes. Data obtained from this study suggests that silencing mutant KRT75 may ameliorate hair phenotypes through restoring the stability of the endogenous keratin intermediate filament network in companion layer keratinocytes.

Although siRNA is highly efficient and specific in silencing mutant keratins and, as this study demonstrated, ex vivo therapy may achieve long-term phenotypic improvement, safety concerns associated with lentiviral vectors prevented the use of lentiviral vector-mediated delivery of shRNA in clinical settings. The development of robust delivery systems through which therapeutic siRNA oligonucleotides can be readily delivered to the site in need of treatment may provide a straight-forward and safe, albeit transient, solution for correcting associated phenotypes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design of mutant Krt75-specific siRNA

A total of 19 possible siRNAs against the previously reported mutant Krt75 (c.545_547 (p.N159del)) (Chen et al., 2008) were designed and synthesized (Thermo Fisher, Shanghai, China) (Figure 1a). Synthetic siRNA duplexes are 21-mers containing two uracyl (U) nucleotide overhangs at the 3’-end of the target sequences, designated consecutively from siN159D-1 to siN159-19 (Figure 1a). A nonspecific siRNA that contains the inverted beta-galactosidase sequence was used as a negative control. A commercial siRNA (SASI_Mm01_00158646, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) directed against the mouse Krt75 gene were used as positive control.

Cell culture and transient transfection

HEK293T cells, which do not express endogenous KRT75, were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. The day before transfection, cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 2.5 × 105 cells per well. Equal amounts (0.5 μg) of wild-type and mutant Krt75 expression plasmids (Chen et al., 2008) were co-transfected with each siRNA (5 − 15 nM) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were harvested 48 hours later for analyses.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells or graft tissues with Trizol (Invitrogen). After DNase (RQ1, Promega, Madison, WI) treatment, 250 ng mRNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA with SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). 15 ng cDNA was used in quantitative PCR. Quantitative real-time PCR for wild-type and mutant Krt75 was performed with an identical primer pair (GeneCore BioTechnologies, Shanghai, China) (Supplemental Figure S1). Two minor groove binder (MGB) probes for allelic-specific assays for wild-type and N159del Krt75 were designed with Primer Express Software (Applied Biosystems v2.0, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) and labeled with FAM and HEX, respectively (GeneCore BioTechnologies) (Supplemental Figure S1). Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out on an ABI 7500 thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Dx, Thermo Fisher). Mouse beta-actin (β-actin, FAM-MGB, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) was used as endogenous control. All experiments were carried out in triplicates in a minimum of three independent experiments. Data were analyzed with the standard curve method. Quantification of Krt1, Krt5, Krt6a, Krt14, and Krt17 were performed with specific TaqMan assays (Krt1, Mm00492992_g1; Krt5, Mm01305291_g1, Krt6a, Mm00833464_g1; Krt14, Mm00495207_m1; Krt17, Mm00495207_m1, Life Technologies). Gapdh (Mm99999915_g1, Life Technologies) was used as an internal control. The ΔΔCt method was used for analyses.

Lentiviral vector construction and production

The shRNAs encoding siN159D-6 and scrambled siRNA (siN159D-6S) were cloned into pLVX-shRNA lentiviral vectors (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) between Pst I and BamH I sites (Supplemental Figure S2). The lentiviral vectors were produced in 293T cells as described elsewhere (Yasuda et al., 2013). Viral vectors were dissolved in serum-containing medium, aliquoted in single-use vials, and stored at −80°C.

Primary keratinocyte culture

Primary keratinocytes were isolated from newborn mice as described previously (Lichti et al., 2008). Specifically, skins of control or mutant Krt75 pups (Chen et al., 2008) were incubated with dispase II (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) to separate the epidermis. Epidermal sheets were then digested with 0.25% trypsin (Life Technologies) to release keratinocytes. The keratinocyte suspension was then cleared through filtration and centrifugation. Keratinocytes were then plated in 10 cm dishes with fibroblast-conditioned medium (Yuspa et al., 1986).

HEK293T or primary keratinocytes were infected with lentiviral vectors as described previously (Yasuda et al., 2013). Briefly, cells growing at approximately 20–30% confluency were treated with 8 μl/ml polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) and infected with concentrated lentiviral vectors overnight. Subsequently, cells were cultured in complete growth medium until harvested for analyses or grafting.

Keratinocyte grafting and hair regeneration

Keratinocyte grafting was performed as described previously (Dai et al., 2011). Specifically, approximately 1 × 106 keratinocytes infected with lentiviral vector were mixed with 2 × 106 primary fibroblasts freshly isolated from newborn pups, and seeded in grafting chamber on the backs of nude (Foxn1−/−) mice. Three weeks later, hair grew out from the graft site. All procedures related to mice were approved by IACUC of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science and Stony Brook University.

Microscopy

Hair plucked from skin grafts or clipped with scissors was used for light microscopy examination. A minimum of one hundred hairs of each experimental group were examined under stereoscope. A hair shaft containing one or more characteristic blebs was recorded as defective. Scanning electron microscopy was carried out as described previously (Chen et al., 2008). Skin grafts were processed without any manipulation on the hair. TM1000 scanning electron microscope (Hitachi High-Technologies, Tokyo, Japan) was used for imaging.

Statistical analyses

All quantifications are presented as mean ± SD. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ning Yang and Dr. Yeun Ja Choi for discussion; David Naimzadeh for assistance in editing; Mallory Korman, Yu-Huan Xu, Yun-Lin Han for assistance in histology; the Departments of Pathology and Dermatology, Stony Brook Stem Cell Facility, and the Cancer Center of Stony Brook University for support. This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31301928) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. DWS201201), and grants from NIH (AR061485 to JC; AR060388, AR059947, and CA052607 to DRR; AR057212 to the SDRC of University of Colorado Denver).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None to declare.

References

- Atkinson SD, McGilligan VE, Liao H, et al. Development of allele-specific therapeutic siRNA for keratin 5 mutations in epidermolysis bullosa simplex. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:2079–86. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapalain V, Winter H, Langbein L, et al. Is the loose anagen hair syndrome a keratin disorder? A clinical and molecular study. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:501–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.4.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Jaeger K, Den Z, et al. Mice expressing a mutant Krt75 (K6hf) allele develop hair and nail defects resembling pachyonychia congenita. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:270–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Roop DR. Genetically engineered mouse models for skin research: Taking the next step. J Dermatol Sci. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai D, Zhu H, Wlodarczyk B, et al. Fuz controls the morphogenesis and differentiation of hair follicles through the formation of primary cilia. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:302–10. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duverger O, Ohara T, Shaffer JR, et al. Hair keratin mutations in tooth enamel increase dental decay risk. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:5219–24. doi: 10.1172/JCI78272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel S, Christiano AM. Genetics of structural hair disorders. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:E22–6. doi: 10.1038/skinbio.2012.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickerson RP, Flores MA, Leake D, et al. Use of self-delivery siRNAs to inhibit gene expression in an organotypic pachyonychia congenita model. J Invest Dermatol. 2011a;131:1037–44. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickerson RP, Leachman SA, Pho LN, et al. Development of quantitative molecular clinical end points for siRNA clinical trials. J Invest Dermatol. 2011b;131:1029–36. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickerson RP, Smith FJ, McLean WH, et al. SiRNA-mediated selective inhibition of mutant keratin mRNAs responsible for the skin disorder pachyonychia congenita. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1082:56–61. doi: 10.1196/annals.1348.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickerson RP, Smith FJ, Reeves RE, et al. Single-nucleotide-specific siRNA targeting in a dominant-negative skin model. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:594–605. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobel M, O'Toole EA, Smith FJ. Keratins and skin disease. Cell Tissue Res. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-2105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane EB, McLean WH. Keratins and skin disorders. J Pathol. 2004;204:355–66. doi: 10.1002/path.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leachman SA, Hickerson RP, Schwartz ME, et al. First-in-human mutation-targeted siRNA phase Ib trial of an inherited skin disorder. Mol Ther. 2010;18:442–6. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie Pedrioli DM, Fu DJ, Gonzalez-Gonzalez E, et al. Generic and personalized RNAi-based therapeutics for a dominant-negative epidermal fragility disorder. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1627–35. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichti U, Anders J, Yuspa SH. Isolation and short-term culture of primary keratinocytes, hair follicle populations and dermal cells from newborn mice and keratinocytes from adult mice for in vitro analysis and for grafting to immunodeficient mice. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:799–810. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean WH, Moore CB. Keratin disorders: from gene to therapy. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:R189–97. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng CS, Wu P, Foley J, et al. The chicken frizzle feather is due to an alpha-keratin (KRT75) mutation that causes a defective rachis. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer J, Langbein L, Rogers MA, et al. Hair follicle-specific keratins and their diseases. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2010–20. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith FJ, Liao H, Cassidy AJ, et al. The genetic basis of pachyonychia congenita. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10:21–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2005.10204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling LC, Hussey S, Sorrells T, et al. Cytokeratin 75 expression in central, centrifugal, cicatricial alopecia--new observations in normal and diseased hair follicles. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:243–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uitto J. Molecular therapeutics for heritable skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:E29–34. doi: 10.1038/skinbio.2012.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uitto J, Richard G, McGrath JA. Diseases of epidermal keratins and their linker proteins. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:1995–2009. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson NJ, O'Toole EA, Milstone LM, et al. The molecular genetic analysis of the expanding pachyonychia congenita case collection. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:343–55. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter H, Langbein L, Praetzel S, et al. A novel human type II cytokeratin, K6hf, specifically expressed in the companion layer of the hair follicle. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:955–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter H, Schissel D, Parry DA, et al. An unusual Ala12Thr polymorphism in the 1A alpha-helical segment of the companion layer-specific keratin K6hf: evidence for a risk factor in the etiology of the common hair disorder pseudofolliculitis barbae. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:652–7. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcik SM, Longley MA, Roop DR. Discovery of a novel murine keratin 6 (K6) isoform explains the absence of hair and nail defects in mice deficient for K6a and K6b. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:619–30. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200102079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda M, Claypool DJ, Guevara E, et al. Genetic manipulation of keratinocyte stem cells with lentiviral vectors. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;989:143–51. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-330-5_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuspa SH, Morgan D, Lichti U, et al. Cultivation and characterization of cells derived from mouse skin papillomas induced by an initiation-promotion protocol. Carcinogenesis. 1986;7:949–58. doi: 10.1093/carcin/7.6.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.