Abstract

Objective(s):

This study aimed to establish a novel non-binding, reversible rat model of acute cholangitis of the severe type (ACST).

Materials and Methods:

Twenty-six rats were randomly divided into the sham-operated group (n=13) and the ACST group (n=13). All rats were intubated with a modified catheter through the external jugular vein. The ACST model was established by ligation of the distal bile duct, placing one end of a modified catheter in the common bile duct, and then injecting lipopolysaccharides from the other end of the catheter and sealing it. The common bile duct pressure was measured before and at 0, 24, 48, and 72 hr after the model was established; similarly, the levels of serum total bilirubin (TBIL), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α were measured at 0, 12, 24, and 48 hr after the model was established.

Results:

Pathological examination of liver tissues was carried out at 24 and 72 hr. The common bile duct pressure increased gradually after the operation. Serum levels of TBIL, ALT, and TNF-α in the ACST group progressively increased and were significantly higher than those in the sham-operated group, at each time point (P<0.05).

Conclusion:

Obvious pathological changes were observed in the liver tissue of rats in the ACST group. This model appears to reflect the early course of human ACST and thus, can be used in postoperative experimental studies of ACST.

Keywords: Acute cholangitis of severe-type, ALT, Common bile duct pressure, Rat model, TBIL, TNF-α

Introduction

Acute cholangitis of the severe type (ACST) is caused by the complete obstruction of the bile duct complicated with biliary infection. It is characterized by the existence of bacterial translocation, gut-derived endotoxemia, and extensive hemodynamic effects caused by the systemic release of inflammatory mediators, which eventually lead to multiple organ dysfunction or failure (1-3). ACST is dangerous and has a high mortality rate because of its rapid onset and development. Therefore, the prevention and treatment of ACST is a relevant issue in medical research. A good animal model provides an important foundation and condition for experimental studies on diseases. Currently, the most widely used animal model for ACST is a rat model established by the complete obstruction of the biliary tract and injection of bacteria or endotoxin into the biliary tract. However, this model is irreversible and cannot clinically resolve ACST, as biliary obstruction is not relieved (4-6). In this regard, we applied a catheter commonly used in epidural anesthesia to establish an unrestrained and reversible ACST rat model, aimed at designing a more suitable model for using in experimental studies.

Materials and Methods

Animals and grouping

Twenty-six clean healthy male Sprague Dawley rats, weighing 227–385 g were offered by the experimental animal center. Animals were raised as matched-pairs according to age (months) and weight, and randomly divided into two groups: the sham-operated group (n=13) and the ACST group (n=13). All animals were fed normally before the operation.

Preparation of catheters

Human epidural anesthesia catheters (F3; Zhejiang Haisheng Medical Apparatus and Instrument Company, Zhejiang, Saoxing, P.R. China) with an outside diameter of 0.9 mm were used. The proximal end (the blunt end with a side hole) of the catheter was cut at about 5 cm. The catheter was then used for catheterization of the common bile duct. The segment cut from the catheter was used for catheterization via the external jugular vein. The catheter’s proximal end was heated and was slightly elongated to enable its flattening in order to prevent piercing of the blood vessel wall.

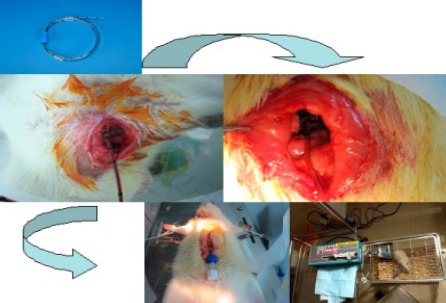

Establishment of the ACST rat model

All animals were fasted with free access to water for 6 hr before the operation (Figure 1). Then, a dose of 50 mg/kg pentobarbital was injected intraperitoneally for anesthesia. After anesthesia, the right external jugular vein was dissected and was ligated at the distal side. A small incision was made in the external jugular vein and a prepared epidural catheter was intubated into the external jugular vein to a depth of 3–4 cm and was fixed with double lines to avoid removal. Then, the other end of the catheter was led from the back of the neck skin and through a spring spiral tube. One end of the spring was fixed on the back of the neck skin with a clip, and the other end was fixed on a supporter outside the rearing cage. The outer end of the catheter was connected to a microcomputer with a digital syringe pump (Alcott Biotech Co., LTD, Shanghai, R.R. China) for transfusion and blood collection during the operation and for the following three consecutive days.

Figure 1.

A flowchart of the technical aspects of the rat model

After the external jugular vein was catheterized, the sham-operated and the ACST models were established under sterile conditions according to the following methods. In the sham-operated group, the abdominal cavity was excised along the ventral midline, the tissues around the common bile duct were dissected bluntly, and then, the abdominal cavity was closed. In the ACST model group, the abdominal cavity was excised along the ventral midline. Then, a small incision was made in the common bile duct, 1 cm away from the confluence of the left and right hepatic ducts, and the distal end was ligated with double lines. Subsequently, a prepared anesthesia catheter was inserted into the proximal end, to a depth of about 6 mm. After being fixed properly, the other end of the catheter was led outside the body and connected to an injection component with a sealing cap. After confirming the patency of the bile output, 10 mg/kg lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and 0.2 ml air were injected into the catheter. The LPS was extracted from Escherichia coli serotype O55:B5 (Sigma Chemical Co., Saint Louis, Missouri, USA). The catheter was then sealed, and the abdominal cavity was closed.

Detection of common bile duct pressure and serological markers

The common bile duct pressure (in cmH2O) of the rats in the ACST group was monitored at 0, 24, 48, and 72 hr after the ligation of the common bile duct with a pressure sensor of type MX9505T (Medex, Inc., Carlsbad, California, USA) connected to the catheter. The serum levels of TBIL and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 0, 12, 24, and 48 hr after injection of endotoxin were determined using an Aeroset automatic biochemical analyzer (Abbott Laboratories, Illinois, USA) and the serum tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) levels at 0, 12, 24, and 48 hr were measured using ELISA (Boster Bio-engineering Co., Ltd, Wuhan, PR China).

Pathological examination

Four rats in each group were chosen at random and euthanized at 24 hr after the model was established. The liver tissue was collected and fixed in 10% neutral formalin. The remaining rats were euthanized at 72 hr after the model was established, and the liver tissue was also collected and fixed in 10% neutral formalin. After 24 hr fixation, paraffin-embedded blocks of liver tissue were prepared according to the conventional methods, sliced, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin dye, and observed with a light microscope.

Statistical analysis

Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were analyzed using the SPSS v17.0 (Chicago, IL, USA). Differences among groups were compared using Student t-test and F test. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Postoperative state

All rats awoke within 1 hr after the operation. Rats in the ACST group appeared fatigued and sallow with dull eyes at 12 hr after the operation. They were also crouching, with oral lip lividity, not eating or drinking, with oliguria and dark yellow urine at 24 hr after the operation. Rats in the sham-operated group drank normally once they were awake, but their activity was slightly decreased. Their general state at 12 hr after the operation was not significantly different from that before the operation. The abdominal cavity of each rat in the ACST group was excised post-mortem to observe the common bile duct. No catheter displacement or bile leakage was observed. Rats in the sham-operated group were healthy at each time phase, and only 1 rat in the ACST group died after 72 hr.

Common bile duct pressures

Rats in the ACST group had higher common bile duct pressure. The pressure increased as the obstruction time was prolonged and reached 11.10±0.72 cmH2O at 72 hr. There were significant differences in common bile duct pressure between the time points (t=10.69, 6.25, and 13.41, P<0.05; Table 1).

Table 1.

The common bile duct pressure of rats in the acute cholangitis of the severe type (ACST) group at different time point.

| Time points (hr) | N | Common bile duct pressure (cmH2O) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 13 | 4.82±0.21 |

| 24 | 13 | 6.47±0.44* |

| 48 | 9 | 7.64±0.42* |

| 72 | 9 | 11.10±0.72* |

Data are shown as mean±SD.

P<0.05, compared with the previous time point using Paired-Sample t-test

Serum indicators

Serum TBIL levels in the sham-operated group did not change significantly across the four time points. However, in the ACST group, serum TBIL levels were increased rapidly as obstruction time increased, and these levels were significantly higher than those in the sham-operated group, at each time point (t=7.28, 12.04, and 11.88, respectively, P<0.05) after 0 hr. Similar to serum TBIL levels, serum ALT and TNF-α levels in the ACST group were also increased sharply, as obstruction time prolonged, and were higher than those in the sham-operated group at 12, 24, and 48 hr after the operation (t=10.03, 28.18, and 20.55; 14.27, 20.67, and 36.89, P<0.05; Table 2).

Table 2.

The serum indicators in both groups of sham and acute cholangitis of the severe type (ACST) group at the different points

| Serum indicators | Groups | 0 hr | 12 hr | 24 hr | 48 hr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBIL (μmol/l) | SHAM | 4.83±1.93 | 5.36±1.64 | 4.52±0.96 | 4.85±1.61 |

| ACST | 5.19±1.23 | 35.39±16.47* | 72.46±21.28* | 108.34±27.54* | |

| ALT (U/l) | SHAM | 24.69±3.86 | 26.23±4.92 | 25.92±4.19 | 24.67±5.24 |

| ACST | 25.46±4.24 | 62.08±17.40* | 162.85±21.54* | 245.22±37.15* | |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | SHAM | 47.25±7.76 | 52.55±9.15 | 48.72±11.26 | 48.20±7.42 |

| ACST | 47.10±7.58 | 114.25±24.09* | 258.69±47.45* | 612.23±51.66* |

Data are shown as mean±SD.

P<0.05, compared with the same time point in the sham operated group using Paired-Sample t-test

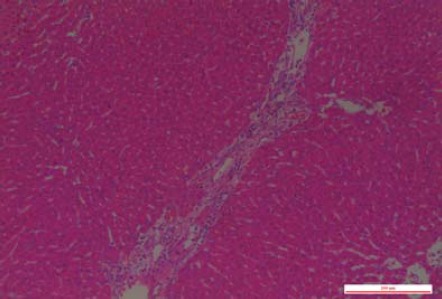

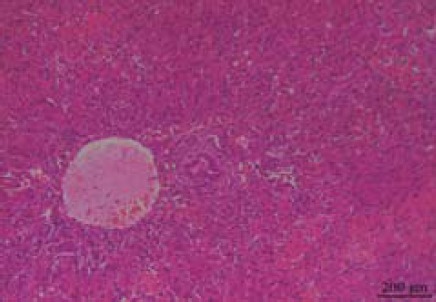

Histopathological changes

There were no obvious gross abnormalities in the liver tissue of the rats in the sham-operated group at 24 or 72 hr after the operation; neither was there any pathological change on light microscopy (Figures 2 and 3). However, in the ACST group, there were obvious histopathological changes in the liver tissue. Small round points of yellow pus, less than 2 mm, were found occasionally on the surface of the liver at 24 hr after the operation; the amount of pus was increased significantly and the liver was enlarged at 72 hr after the operation. As observed under a light microscope, hepatocytes were edematous with spotty necrosis, and the portal area was infiltrated with inflammatory cells at 24 hr after the operation (Figure 4). At 72 hr after the model was established, hepatocytes showed patchy necrosis, and the portal area was more obviously infiltrated by inflammatory cells (Figure 5).

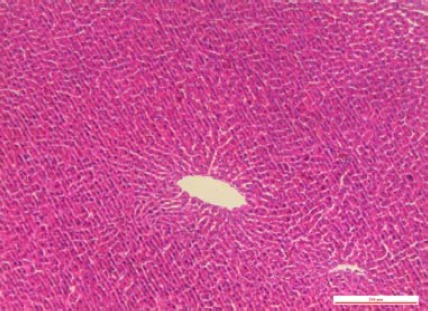

Figure 2.

In the sham-operated group at 24 hr after the operation, light microscope showed no pathological change

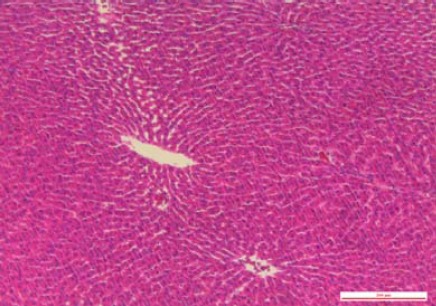

Figure 3.

In the sham-operated group at 72 hr after the operation, light microscope showed no pathological change

Figure 4.

In the acute cholangitis of the severe type (ACST) group at 24 hr after the operation, hepatocytes showed edema and spotty necrosis, and the portal area was infiltrated with the inflammatory cells

Figure 5.

In the acute cholangitis of the severe type (ACST) group at 72 hr after the model established, hepatocytes showed patchy necrosis and the portal area was infiltrated with the inflammatory cells more obviously

Discussion

ACST is caused by obstruction of the bile duct, which causes increased pressure in the bile duct, cholestasis, and bacterial translocation and propagation. The purulent bile flows back under high pressure to the portal vein and the surrounding hepatic lymphatic vessels, and causes a systemic sepsis (7, 8).

There are several methods to establish ACST animal models. However, direct injection of bacteria or mere biliary obstruction can only simulate a single factor such as infection or obstruction, which simulate the disease poorly (9, 10). Currently, the complete obstruction combined with infection model is widely used, which is established with biliary obstruction and injection of bacteria (4-6, 11). This model is reliable and shows obvious pathological changes. However, more in-depth research is required, as a second surgery is needed for de-obstruction. This is more difficult to achieve an experimental model of bile duct ligation combined with internal drainage, as the trauma caused is severe, and the complications and mortality rates are high (12, 13). Higure A et al had established an ACST rabbit model (14) and ohta T et al had established an ACST canine model (15). Further, horses and other large animals can be used to establish an ACST model (16). All these models were established by ligation of the distal common bile duct, leading the internally installed tube to be outside the body, and by injecting bacteria into the tube. This modeling method has the advantages of easy catheterization, easy obstruction control, and is almost similar to natural clinical progression. However, such animal models are expensive, and experiments on these cannot be carried out widely. Restraint of large animals is also a large practical problem.

In this study, a rat was used to establish an ACST model by using an epidural anesthesia catheter. This is easy to operate and control due to the scale on the catheter. Furthermore, the epidural anesthesia catheter can be used for multiple purposes in this operation. During the operation, we first established an external jugular vein infusion system, and then applied the spiral spring to fix the tube to the rats, so that the rats could be unrestrained after the operation, whilst providing a guaranteed access for postoperative continuous infusion and multiple collections of blood samples.

Anatomically, the common bile duct is surrounded by pancreatic tissue. The pancreatic secretory ducts join into a larger duct and then, join the common bile duct. Thus, in order to avoid injury to the pancreas, the catheterization was performed 1 cm away from the confluence of the left and right hepatic ducts. The bile duct wall is thin, so catheterization is difficult and is prone to bile leakage in cases of high biliary pressure; this is most difficult during the establishment of a rat ACST model. The head-end being small and blunt and its natural curvature because of coiling, the epidural anesthesia catheter is easy to use, thus reducing the possibility of damage to the common bile duct. The distal common bile duct and the proximal end of the internal catheter were both fixed with double lines of silk thread. During the operation, the endotoxin was injected without any visible leakage. Post-mortem, no catheter displacement, bile leakage, or perforated biliary ducts were found. The component with the sealing cap used to seal the tube, enables a sterile and active operative condition and a closed conduit, thus significantly reduces the risk of additional infection and improves the success rate of modeling.

In the study, only 1 rat in the ACST group died after 72 hr, which indicates that the clinical features of ACST were more closely represented in this model, and that the model could have higher success rate, as appropriate catheterization was possible and the obstruction was easy controlled. In the past, the mortality rate of ACST rat models was up to 50%. Further study should be performed to validate whether endotoxin should be used instead of E. coli, to determine whether adult rats having strong resistance for disease should be used in the study, and to observe the mortality rate with a longer follow-up time. Our results showed that the common bile duct pressure in the ACST group increased gradually after surgery. Compared to the sham-operated group, the serum TBIL level at each time point was elevated sharply. Normal rat bile duct pressure is approximately 4.5 cmH2O, and the normal serum bilirubin level is 4 µmol/l. However, as the common bile duct is obstructed, the pressure within the entire biliary system increases significantly due to cholestasis and causes mechanical breakage of the ampulla connecting the cholangioles and canals of Hering. The bile then enters into the lymphatic vessels directly. In addition to the disordered secretory function of hepatocytes, obstructive jaundice occurs. In this study, we injected endotoxin into the common bile duct rather than bacteria, because sepsis is an important cause of the high mortality rate of ACST disease. Bacterial endotoxin may be a more important factor than bacterial infections seen in multiple organ failure syndromes (MODS). Clinically, even though there is no evidence of bacteremia in ACST patients, endotoxemia and high levels of serum TNF-α are usually seen (2, 17). Endotoxin-induced cytokines play an important role in the occurrence and development of sepsis. Our results showed that the serum TNF-α levels were significantly higher at each time point in the ACST group than those of the sham-operated group. The potential mechanism is that cholestasis induces LPS hypersensitivity, and the expression of endotoxin receptor CD14 in liver cells is enhanced progressively, so that the downstream signaling pathways of TLR4 are activated, which activate NF-κB to direct transcription of target genes. Consequently, the expression of TNF-α and other inflammatory factors is enhanced progressively (18, 19). Inflammatory factors also exacerbate the infiltration of inflammatory cells in the liver tissue and lead to hepatocyte degeneration and necrosis.

This preliminary experimental result showed that rat ACST model represents the clinical features of ACST more closely and can reflect the early course and lesions of human ACST. Since the catheter is retained in the common bile duct, it can also be used for the further experimental studies on ACST.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by Zhejiang Provincial Public Welfare Technology Application Research Projects under grant no.2011C33023, and Research Foundation of Health Bureau of Zhejiang Province under grant no.2013RCB018.

Conflicts of interest

All of the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding this paper.

References

- 1.Stewart L, Oesterle AL, Grifiss JM, Jarvis GA, Way LW. Cholangitis: bacterial virulence factors that facilitate cholangiovenous reflux and tumor necrosis factor-alpha production. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:191–198. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(02)00133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanazawa A, Kinoshita H, Hirohashi K, Kubo S, Tsukamoto T, Hamba H, et al. Concentrations of bile and serum endotoxin and serum cytokines after biliary drainage for acute cholangitis. Osaka City Med J. 1997;43:15–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tu B, Gong JP, Feng HY, Wu CX, Shi YJ, Li XH, et al. Role of NF-κB in multiple organ dysfunction during acute obstructive cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:179–183. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miao HL, Qiu ZD, Hao FL, Bi YH, Li MY, Chen M, et al. Significance of MD-2 and MD-2B expression in rat liver during acute cholangitis. World J Hepatol. 2010;2:233–238. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v2.i6.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watanabe K, Yokoyama Y, Kokuryo T, Kawai K, Kitagawa T, Seki T, et al. 15-deoxy-delta 12,14-prostaglandin J2 prevents inflammatory response and endothelial cell damage in rats with acute obstructive cholangitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G410–G418. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00233.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu H, Wu SD. Activation of TLR-4 and liver injury via NF-kappa B in rat with acute cholangitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:185–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karsten TM, van Gulik TM, Spanjaard L, Bosma A, van der Bergh Weerman MA, Dingemans KP, et al. Bacterial translocation from the biliary tract to blood and lymph in rats with obstructive jaundice. J Surg Res. 1998;74:125–130. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1997.5192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White JS, Hoper M, Parks RW, Clements WD, Diamond T. Patterns of bacterial translocation in experimental billary obstruction. J Surg Res. 2006;132:80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang ZK, Xiao JG, Huang XF, Gong YC, Li W. Effect of biliary drainage on inducible nitric oxide synthase, CD14 and TGR5 expression in obstructive jaundice rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2319–2330. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i15.2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raper SE, Barker ME, Jones AL, Way LW. Anatomic correlates of bacterial cholangiovenous reflux. Surgery. 1989;105:352–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gong JP, Wu CX, Liu CA, Li SW, Shi YJ, Li XH, et al. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cell injury by neutrophils in rats with acute obstructive cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:342–345. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i2.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan CJ, Than T, Blumgart LH. Choledochoduo-denostomy in the rat with obstructive jaundice. J Surg Res. 1977;23:321–331. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(77)90069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W, Chung SC. An improved rat model of obstructive jaundice and its reversal by internal and external drainage. J Surg Res. 2001;101:4–15. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higure A, Okamoto K, Hirata K, Todoroki H, Nagafuchi Y, Takeda S, et al. Macrophages and neutrophils infiltrating into the liver are responsible for tissue factor expression in a rabbit model of acute obstructive cholangitis. Thromb Haemost. 1996;75:791–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohta T, Nagakawa T, Tsukioka Y, Sanada H, Miyazaki I, Terada T. Proliferative activity of bile duct epithelium after bacterial infection in dogs. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:845–851. doi: 10.3109/00365529209000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis JL, Jones SL. Suppurative cholangiohepatitis and enteritis in adult horses. J Vet Intern Med. 2003;17:583–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saia RS, Bertozi G, Mestriner FL, Antunes-Rodrigues J, Queiróz Cunha F, Cárnio EC. Cardiovascular and inflammatory response to cholecystokinin during endotoxemic shock. Shock. 2013;39:104–113. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182793e2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daubeuf B, Mathison J, Spiller S, Hugues S, Herren S, Ferlin W, et al. TLR4/MD-2 monoclonal antibody therapy affords protection in experimental models of septic shock. J Immunol. 2007;179:6107–6114. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.6107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou MH, Chuang JH, Eng HL, Tsai PC, Hsieh CS, Liu HC, et al. Effects of hepatocyte CD14 upregulation during cholestasis on endotoxin sensitivity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]