Abstract

Background:

The pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes is characterized by insulin resistance and insulin secretory dysfunction. Few existing metabolic tests measure both characteristics, and no such tests are inexpensive enough to enable widespread use.

Methods:

A hierarchical approach uses 2 down-sampled tests in the dynamic insulin sensitivity and secretion test (DISST) family to first determine insulin sensitivity (SI) using 4 glucose measurements. Second the insulin secretion is determined for only participants with reduced SI using 3 C-peptide measurements from the original test. The hierarchical approach is assessed via its ability to classify 214 individual test responses of 71 females with an elevated risk of type 2 diabetes into 5 bins with equivalence to the fully sampled DISST.

Results:

Using an arbitrary SI cut-off, 102 test responses were reassayed for C-peptide and unique insulin secretion characteristics estimated. The hierarchical approach correctly classified 84.5% of the test responses and 94.4% of the responses of individuals with increased fasting glucose.

Conclusions:

The hierarchical approach is a low-cost methodology for measuring key characteristics of type 2 diabetes. Thus the approach could provide an economical approach to studying the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes, or in early risk screening. As the higher cost test uses the same clinical protocol as the low-cost test, the cost of the additional information is limited to the assay cost of C-peptide, and no additional procedures or callbacks are required.

Keywords: a posteriori identification, hierarchical testing, insulin secretion, insulin sensitivity, type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is very costly in personal and economic terms and is increasing in prevalence globally.1,2 Obesity, increasingly sedentary lifestyles, environmental factors, and genetic predisposition have been implicated as the causes of type 2 diabetes.3-5 Intervention measures such as intensive exercise or dieting can mitigate or offset the onset of the disease.5-7 However, such methods have not been utilized widely, as it is not economically feasible to provide such interventions across wide population groups. However, if health care systems could recognize individuals with significant risk very early, there is potential for economic and personal benefit. The tools used to recognize individuals sufficiently early on the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes must be of low cost to be economically sustainable and of low intensity.

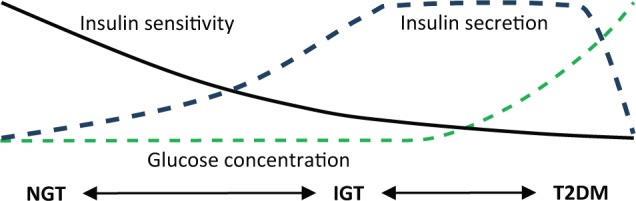

The typical pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes progresses through 3 distinct stages.8 In comparison to NGT, IGT is characterized by low insulin sensitivity (SI), high insulin secretion rates (UN), and equivalent basal glucose (G0).8-10 This state of high UN and low SI often occurs before the formal diagnosis of diabetes. While early-onset diabetes is often associated with hypersecretion, late-onset diabetes is typically characterized by a decline UN, coupled with insulin resistance, this causes an increase in G0 .8,11-15 Insulin sensitivity typically reduces during the progression of type 2 diabetes,16-19 but most measures of SI lose resolution at lower values.20 The changes in SI, UN, and G0 during the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes are summarized in Figure 1 and Table 1.

Figure 1.

Typical pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Typical Type 2 Diabetes Development With Respect to NGT Individuals.

| G0 | SI | UN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IGT | = | ↓ | ↑ |

| Type 2 diabetes | ↑ | ↓ | ↑↓a |

Insulin secretion typically reduces from hypersecretion to hyposecretion as the diabetic state exacerbates.

The dynamic insulin sensitivity and secretion test (DISST) was designed to capture high resolution estimates of SI and UN which are the key metabolic indicators of the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes and thus assess the risk or severity of the disease.21-23 Later analysis revealed that accurate SI values could be obtained using only the low-cost glucose assays.24,25 A spectrum of DISST tests showed that a range of accuracy and cost trade-off existed when different species from the blood samples from a single test are measured.26 This outcome implies that a single clinical protocol could yield results of differing cost and accuracy depending on the nature of the assays taken.

These outcomes enable a hierarchical approach wherein the lower cost tests can be used to screen a population, and the higher cost tests can be used to provide specificity or added information where the value is most needed. Since stored samples can be assayed for further species, only a single test needs to be performed. This article presents a novel hierarchical approach that provides SI and UN information for participants that were recognized as insulin resistant via a low-cost test.

Methods

Cohort

Seventy-one female participants from the Otago region of New Zealand were recruited to take part in a longitudinal study of dietary protein.27 Participants were randomized to either a high protein 30/40/30% protein/carbohydrate/fats, or high fiber 20/50 to 60/20 to 30% diets. Study participants were selected based on increased risk of diabetes and metabolic disease based on BMI (>25 kg/m2) or a genetic disposition to type 2 diabetes via ethnicity or family history. Subjects underwent a DISST test and had physical measurements taken at weeks 0, 12, and 24 of a randomized control trial measuring the effect of high protein dietary intervention. Full details of the trial can be seen in Te Morenga et al.27

DISST Protocols

Subjects fasted from 10 p.m. on the night prior to undertaking the DISST protocol. The subjects were seated in a reclined position and had a cannula placed in the antecubital fossa. A 10 g bolus of glucose (50% dextrose) was administered via the cannula at t = 1 minutes followed by a 1U insulin bolus (actrapid) at t = 11 minutes. Blood samples were taken via the same cannula at t = 0, 5, 10, 20, and 30 minutes. All samples were spun then frozen for later batch assays of glucose (Cobas Mira analyzer, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), insulin (Roche Elecsys after polyethylene glycol [PEG] precipitation of immunoglobulins), and C-peptide (Roche Elecsys methods).

DISST Model and Parameter Identification

The DISST model was used to model participant-specific behavior based on their measured glucose insulin and C-peptide responses to the clinical protocol.21,28 The model is defined as

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

where nomenclature is defined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Model Nomenclature and Roles During the Identification Process.

| Symbol | Meaning | Units | Approach role |

|---|---|---|---|

| G | Glucose concentration | mg·dL-1 | Measured/modeled |

| I | Plasma insulin concentration | mU·L-1 | Measured/modeled |

| Q | Interstitial insulin concentration | mU·L-1 | Modeled |

| C | Plasma C-peptide concentration | pmol·L-1 | Measured/modeled |

| Y | Interstitial C-peptide concentration | pmol·L-1 | Modeled |

| SI | Insulin sensitivity | mU·L-1 | Identified |

| UN | Insulin secretion rate | mU·L-1·min-1 | Identified/estimateda |

| nT | Plasma insulin clearance rate | min-1 | Identified/estimateda |

| xL | Proportion of first pass extraction | 1 | Identified/a prioria |

| nI | Plasma-interstitial insulin transport rate | L·min-1 | a priori |

| nC | Rate of insulin binding to cells | min-1 | a priori |

| k1-3 | C-peptide kinetic parameters | min-1 | a priori |

| pG | Rate of glucose dependent uptake | min-1 | a priori |

| VG, VP, VQ | Distribution volumes of glucose, plasma insulin and interstitial insulin, respectively | L | a priori |

The full DISST uses all available samples, and will be used as a comparator in this study. Information on the parameter identification methodology can be seen in Lotz et al.21 The DISST hierarchy requires identification of 2 distinct sets of data from the same clinical protocol. The DISTq requires 4 of the 5 available glucose samples (t = 0, 10, 20, 30).24,25 The DISTqUN requires 4 of the available 5 glucose samples (t = 0, 10, 20, 30), and 3 of the available C-peptide samples (t = 0, 10, 30).

The DISTq parameter identification method uses an initial estimate of the test participant’s insulin response to the clinical protocol as input to the identification of SI and VG using the iterative integral method29 with equation 5. An improved estimate of the participant’s insulin response can be made by determining the typical nT and UN values for the specific identified SI value. This approach allows an update of the SI via the improved input to the inverse problem. This process is iterated until convergence. Full details can be seen in Docherty et al.24,25

The DISTqUN uses a similar process to the DISTq.26 However, instead of using the SI values to predict UN, this vector is determined via the deconvolution approach typical of the full DISST.21,30 The nT parameter is still iteratively updated by the SI values. The value of xL is set at 0.7 for both DISTq and DISTqUN.31,32

The full DISST uses all of the samples to identify UN via deconvolution of equations 1 and 2. The UN profile is divided into 3 distinct periods. The basal insulin secretion rate (UB); the first phase insulin secretion (U1) and the second phase secretion (U2). UB is the first value of the UN profile (mU⋅L-1⋅min-1). U1 is the area under the UN profile from t = 5 to 10 minutes (mU⋅L-1) and U2 is the area under the UN profile from t = 10 to 30 minutes (mU⋅L-1). The nT and xL parameters were identified via the iterative integral method and equations 3 and 4. SI and VG are identified via the iterative integral method and equation 5. The remaining a priori values are determined via the equations defined by Van Cauter et al.33

The objective of the hierarchy of DISST tests is to determine the progression of type 2 diabetes for as little cost as possible. To reduce cost, a 2-stage test is proposed. The participant reports to undergo a DISST test and 5 blood samples are taken. Four of the samples are assayed for glucose straight away, and SI is estimated using the DISTq methodology. If this SI value falls below a certain threshold, the t = 0, 10, and 30 minute samples are then assayed for C-peptide. C-peptide assays are not typically available immediately. This analysis measures the C-peptide levels in blood samples of those participants that obtained an SI value of less than 8 × 10-4 L⋅mU-1⋅min-1 according to the DISTq and the 4 glucose samples.

Analysis

Spearman correlation and receiver operator characteristic curves (ROC) were used to compare SI values obtained by the fully sampled DISST to those obtained by DISTq. The ROC will use a diagnostic threshold of 7 × 10-4 L⋅mU-1⋅min-1 for insulin resistance in the absence of an established SI value for these purposes. The 8 × 10-4 L⋅mU-1⋅min-1 reassay threshold was determined to allow the hierarchy approach the ideal chances of correctly diagnosing participants about this threshold. This analysis will be repeated for the insulin sensitivity values obtained when samples from the qualifying tests are reassayed for C-peptide.

The hierarchy will be assessed via its ability to classify the patient states by defining a number of bins as shown in Table 3. The G0 threshold was 5.5 mmol⋅L-1 according to the ADA classification.34 The SI and U2 classifier thresholds were arbitrarily chosen at 7 × 10-4 L⋅mU-1⋅min-1 and 300 mU⋅L-1, respectively. Although there have been a number of studies that link SI and U2 to the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes, there have been no declared and accepted values of elevated risk. Hence, it was necessary to determine arbitrary values. The median SI value for the cohort was approximately 7 × 10-4 L⋅mU-1⋅min-1 and the 75th percentile U2 value was approximately 300 mU⋅min-1. The bins can be broadly considered as 1, NGT; 2, IGT; 3, IGT—hypersecretory; 4, IFG—hypersecretory; 5, IFG—hyposecretory. These groups allow a discrimination of key patient states for optimal application of intervention or therapy. Note that it is possible for individuals to escape classification if they have high insulin sensitivity and high fasting glucose.

Table 3.

Bins Classifying the Participant Responses to the DISST Test.

| Bin |

G0

mg·dL-1 |

SI

L·mU-1·min-1 |

U2

mU·L-1·min-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | <100 | >7 × 10-4 | — |

| 2 | <100 | <7 × 10-4 | <300 |

| 3 | <100 | <7 × 10-4 | >300 |

| 4 | >100 | <7 × 10-4 | >300 |

| 5 | >100 | <7 × 10-4 | <300 |

Results

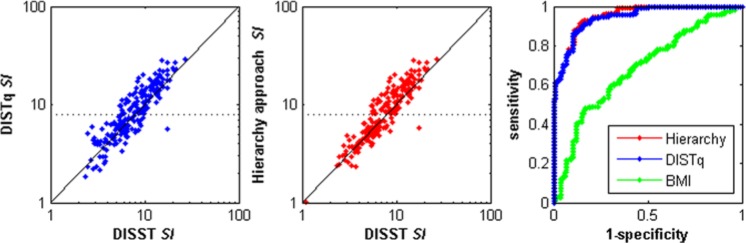

Using a retest threshold of SI < 8 × 10-4 mU.L-1.min-1 as measured by the DISTq meant that samples from 102/214 tests in this “at-risk” cohort were reassayed for C-peptide. Hence, the mean assay cost per person of the cohort was ~NZ$10 (~US$8.5) for DISTq, ~NZ$115 (~US$99) for DISTqUN and ~NZ$55 (~US$47) for the hierarchical approach. Table 4 shows correlations and diagnostic equivalence between the various down-sampled tests and the fully sampled DISST. As expected, the hierarchy approach represented a compromise between the lower cost DISTq and the higher cost DISTqUN. Figure 2 shows how the SI values were distributed about the retest point, and how the up-sampled analysis altered the diagnostic potential of SI. Figure 3 shows the distribution of second phase insulin secretion values and the improvement in diagnostic ability of the metric after the qualifying test samples were reassayed.

Table 4.

Correlation and ROC Analysis of SI Values From the Lower Cost Approaches and the Fully Sampled DISST.

| BMI | DISTq | DISTqUN | Hierarchy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI correlation | −.37 | .88 | .93 | .90 |

| SI ROC c-unit | .69 | .94 | .97 | .95 |

| UB correlation | .51 | .52 | 1.00 | .71 |

| UB ROC c-unit | .78 | .74 | 1.00 | .84 |

| U1 correlation | .12 | −.08 | .99 | .61 |

| U1 ROC c-unit | .57 | .53 | 1.00 | .84 |

| U2 correlation | .44 | .67 | .97 | .80 |

| U2 ROC c-unit | .67 | .83 | .98 | .92 |

Figure 2.

Comparison of insulin sensitivity values across the fully sampled DISST, DISTq, and the 2-stage hierarchal approach. The receiver operator curve was evaluated using a cutoff IS value of 7 × 10-4 L·mU-1·min-1. The dotted line shows the retest threshold.

Figure 3.

Distribution of the second phase insulin secretion content as determined by the fully sampled DISST and the reduced sample tests. The receiver operator curve was determined using a U2 value of 300 mU.min-1.

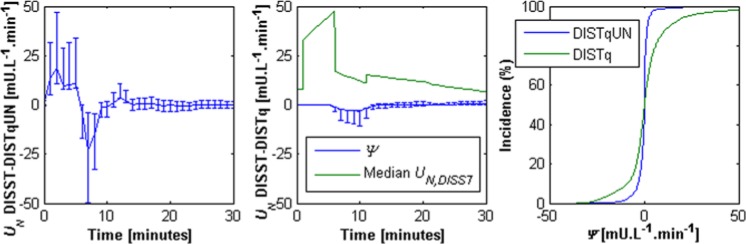

While DISTqUN and the hierarchy captured both SI and UN relatively well, DISTq effectively captured SI alone. This was an intended outcome of the hierarchy design as the low-cost SI value can be identified in real time and used to determine the insulin resistance subjects for whom UN information would be beneficial. The appendix shows the differences between the UN profiles estimated via the DISST and the down-sampled approaches.

Table 4 and Figures 2 and 3 show the ability of BMI to classify insulin resistance and hypersecretion, respectively. Obesity (BMI > 30) constituted 57/112 (50.9%) of group 1 as defined by the DISST, 35/46 (76%) of group 2, 30/36 (83.3%) of group 3, 6/7 (85.7%) of group 4, and 11/11 of group 5. Hence, in this cohort, the rate of obesity rose as the grouping criteria defined increasingly exacerbated states on the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. However, the ROC c-units for BMI to SI and UN show that BMI has very limited potential to capture or contrast the key metabolic signals of prediabetes.

Table 5 shows the correct reclassification rates of the various tests. Note that scores along the main diagonal represent correct reclassification and that groups 4 and 5 represent elevated fasting glucose (>100 mg⋅dL-1). Since all approaches measure fasting glucose, all were able to determine this threshold with full precision. The discrimination of groups 2 and 3 as well as groups 4 and 5 was done in terms of U2. Those that evaded classification (n = 3) had a high insulin sensitivity value (>7 × 10-4 mU.L-1.min-1) and a high basal glucose value (>5.6 mg⋅dL-1), and thus represented an unexpected state. The hierarchical approach correctly reclassified 181/214 trials (84.6%) whereas the DISTq test correctly reclassified 161/214 trials (75.2%).

Table 5.

Reclassification Rates for the Hierarchical Approach and the DISTq Approach.

| Classification by DISTq + DISTqUN hierarchy |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DISST outcome | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | UC |

| 1. (n = 112) | 92.0% | 8.0% | — | — | — | — |

| 2. (n = 46) | 30.4% | 52.2% | 17.4% | — | — | — |

| 3. (n = 36) | 2.8% | — | 97.2% | — | — | — |

| 4. (n = 7) | — | — | — | 100% | — | — |

| 5. (n = 11) | — | — | — | 9.1% | 90.9% | — |

| UC (n = 2) | — | — | — | — | — | 100% |

| Classification by DISTq only |

||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | UC | |

| 1. (n = 112) | 92.9% | 7.1% | — | — | — | — |

| 2. (n = 46) | 32.6% | 50.0% | 17.4% | — | — | — |

| 3. (n = 36) | 11.1% | 25.0% | 63.9% | — | — | — |

| 4. (n = 7) | — | — | — | 85.7% | 14.3% | — |

| 5. (n = 11) | — | — | — | 63.6% | 36.4% | — |

| UC (n = 2) | — | — | — | — | 50.0% | 50.0% |

UC, unclassified.

Discussion

The SI value obtained by DISTq was equivalent (R = .88, c-unit = .94) to the hierarchical SI values (R = .90, c-unit = .95) in terms of its ability to replicate the values obtained by the fully sampled DISST (Figure 2, Table 4). Hence, if SI values are the only metric of importance to a particular application, there is no justification for the increased expenditure to obtain the necessary measurements for DISTqUN. However, the ability of a subject to secrete insulin is of paramount importance to early recognition of diabetes risk, pretreatment, screening applications, or studies that seek to determine the etiology of type 2 diabetes.35-37

The hierarchical approach allows a low-cost method of obtaining insulin secretion information from only the individuals of interest, without the need for an additional test. The low-cost DISTq test uses the glucose data to determine the test participants level of insulin resistance in real time and provides an indication of where more expensive C-peptide assays will be most useful in describing the participants UN profile. While this study concentrated on the methods ability to reclassify participants in terms of SI and U2, the methodology will yield a full UN profile for all individuals classed as insulin resistant by the DISTq. Hence, clinicians will have information on the insulin resistant participants’ basal insulin secretion rate, first phase and second phase secretion rates and the ratio of first to second phase insulin secretion.38

The DISTq estimates insulin secretion based on the participant’s insulin sensitivity.24,25,39 Hence, UN values from the DISTq are not patient specific and cannot be used for discrimination. The DISTq U2 values were evenly distributed about the 1:1 line with respect to the fully sampled DISST (Figure 3), indicating an limited bias across the cohort and confirming the overall DISTq approach. However, the individual U2 values obtained by DISTq were not sufficiently correlated to the values obtained with the fully sampled test to make accurate conclusions regarding the patients’ secretory capability (Figure 3). In contrast, DISTqUN captured U2 values that were very similar to the fully sampled DISST (R = .96, c-unit = .99, Table 3). Hence, the lower cost DISTqUN is capable of capturing patient specific insulin secretion characteristics that are critical to determining the individual’s location on the progression of diabetes (Figure 2, Table 3).8,14,40

Taking C-peptide samples at t = 0, 10, and 30 minutes allows direct and unique identification of UB, U1, and U2 for a minimal cost. These secretion metrics provide value for distinct clinical research and screening applications. UB quantifies the rate of insulin secretion required to maintain the fasting glucose rate and elevated rates have been linked to diabetes risk.3,41 U1 is sometimes referred to as the acute insulin response and becomes blunted during the establishment of diabetes.42 Hence, it is an important aspect for the characterization of the metabolic responses of IGT and IFG participants. However, U1 values were not incorporated into the classification bins of this analysis to avoid excessive complexity of interpretation. U2 can determine how much insulin a healthy individual needs to release in response to glucose and how much an individual with diabetes is able to release in response to glucose. Hence, in healthy individuals, a lower secretion is often coupled with a higher SI and is preferable. In contrast, a lower U2 among individuals with diabetes is considered to imply an inability to produce sufficient insulin and is linked to the degree of hyperglycemia.8,14 In the full DISST, U2 showed the best discrimination of all secretion metrics.22

Table 5 shows the ability of the hierarchical approach to reclassify the various states on the progression of type 2 diabetes and compares the classification determined by the DISTq alone. In comparison to the DISTq, the hierarchical approach showed particular improvement in the identification of hypersecretion in insulin resistant patients. However, both protocols exhibited similar ability to reclassify those in group 2. In both cases, a similar number of trial responses were incorrectly reclassified to IGT hypersecretory and NGT. Hence, the errors were due to reduced resolution in SI and UN. The DISTq parameter identification method estimates higher insulin secretion for patients with lower SI. Thus DISTq estimated higher insulin secretion rate than was measured for the insulin resistant individuals in the IFG hyposecretory group, and classified them in the IFG hypersecretory group.

BMI is an import risk factor for insulin resistance, the development of type 2 diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome.43,44 In this present study BMI showed some limited ability to determine the insulin resistance or hypersecretion. However, its diagnostic ability for insulin resistance fell well short of the DISTq and hierarchy approach and its diagnostic ability for hypersecretion was less than that of the hierarchy method. Interestingly, the rate of obesity increased as the grouping criteria described exacerbated states of type 2 diabetes. However, this cannot be used as a diagnostic as over 50% of the comparatively healthy group 1 test responses were from individuals that were classed as obese.

In this analysis, the retest threshold was set at an arbitrary value of SI < 7 × 10-4 mU.L-1.min-1. This value was close to the median DISTq SI value obtained. As, the recruitment criteria was weighted toward individuals who were at risk of developing type 2 diabetes, using an SI value close to the median is a reasonable estimate. Hence, the cohorts were moderately insulin resistant, and in a wider population, the retest rate would be considerably less. In particular, if the hierarchical approach were used in a diabetes risk screening program, approximately >30% of a Western population could be excluded prior to testing due to age, existing diabetes, or levels of physical exercise. Only ~30% of the population would require the up-sampled test and the cost per participant could be as low as NZ$36 of assay cost per person on average. Importantly, the DISTq only requires glucose measurements, and as these are typically available in real time, the test result would be known immediately and thus whether reassay of test samples for C-peptide is necessary would also be known immediately.

It should be noted that the fasting glucose measurement could not be used in a hierarchy to instigate a higher accuracy test. In particular, only 18 of 214 tests yielded elevated basal glucose measurements whereas 102 of 214 exhibited signs of metabolic risk as defined by the SI threshold. If only those that had elevated basal glucose levels underwent a DISST test, all participants that were in groups 2 and 3 would not be recognized as at risk of metabolic dysfunction given their reduced insulin sensitivity or secretory capability.16-19 Individuals in groups 2 and 3 are perhaps of the greatest importance to screening and clinical research into the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes.

Furthermore, this analysis yields insulin secretory information that provides a more complete observation of a patient’s glycemic metabolism than would be possible with HbA1c measurements. In particular, HbA1c is a measure of average daily glucose45 and is thus not able to directly observe or delineate changes in insulin secretion capability, insulin sensitivity or nutritional intake. In particular, individuals in groups 3 and 4 can potentially maintain moderately healthy glucose levels despite insulin resistance by maintaining insulin hypersecretion.13 It has been shown that hypersecretion is an important risk-factor for the development of type 2 diabetes.11,12 This critical condition on the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes would be undetectable with HbA1c.

This proof of concept study was conducted using data from 71 nondiabetic women who met the recruitment criteria of an increased risk of developing diabetes. Increased risk was defined as a BMI greater than 25 kg.m-2 or a BMI greater than 23 kg.m-2 coupled with a family history or ethnic disposition toward diabetes. Hence, the cohort yielded glycemic abnormalities such as IGT, IFG, prediabetes, and hypersecretion with a greater rate of incidence would be expected from the general nondiabetic public. As the proposed hierarchy of tests was intended to exist in a wider hierarchy wherein those that are not considered at risk are not tested, this cohort was appropriate to measure the efficacy of the approach.

However, testing the efficacy of the overall approach for population screening should be undertaken with quite different experimental design. In particular, screening is only of value if it can prompt intervention that has long lasting patient benefits and lessens the economic burden on health care systems. Testing the efficacy of the overall approach must incorporate some intervention to mitigate or offset the onset of diabetes and precisely quantity the potential for successful intervention and resulting economic costs and benefits.

Measuring insulin sensitivity is often limited to epidemiological studies of type 2 diabetes or the metabolic syndrome. One of the barriers to more widespread uptake of such tests is the cost involved with established tests that are known to have sufficient accuracy. The hierarchical approach presented here was intended to yield the maximum possible information for a minimal cost. Hence, those that were deemed healthy at a cost of NZ$5 did not have their test samples reassayed. Those that were indicated to have lower insulin sensitivity with the lower cost test had blood samples that previously obtained in the DISTq protocol reassayed for C-peptide. The reassay allowed both a more accurate SI value, and patient specific insulin secretion characteristics to be obtained.

Conclusions

We have presented a novel hierarchical approach for low-cost and informative glycemic testing. The hierarchy allows many participants to be classified as healthy with a relatively inexpensive test, and can reclassify the remaining individuals for a moderate increase in cost, and no further clinical protocol. Hence, clinical research and screening applications that were previously impossible due to the high cost of the available insulin sensitivity and secretion tests may now be feasible. However, an economic analysis of the cost and potential benefits of such programs must be fully considered in further study.

Appendix

The DISTq UN profiles were estimated via an a posteriori function of insulin sensitivity, and were thus quite different to the profiles determined by the fully sampled DISST. The median absolute difference between the DISTq and DISST UN profiles was 3.56 mU⋅L-1⋅min-1 (IQR: 1.42 to 8.48 mU⋅L-1⋅min-1). In contrast, the profiles determined via DISTqUN were more similar to the fully sampled DISST. The median absolute difference in UN values was 0.69 mU⋅L-1⋅min-1 (IQR: 0.11 to 1.86 mU⋅L-1⋅min-1). Figure A1 shows the differences between the UN profiles determined by the approaches.

Figure A1.

Median difference (ψ) between the UN profiles estimated by the DISTq and the DISST (left); the DISTqUN and DISST (center). Error bars show the interquartile range. The median UN response is shown for scale. The cumulative distributions of differences in UN estimation for the 2 methods in comparison to the DISST are shown on the right.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DISST, dynamic insulin sensitivity and secretion test; DISTq quick dynamic insulin sensitivity test; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; NGT, normo-glucose tolerant; SI, insulin sensitivity.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Lam DW, LeRoith D. The worldwide diabetes epidemic. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2012;19(2):93-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gakidou E, Mallinger L, Abbot-Klafter J, et al. Management of diabetes and associated cardiovascular risk factors in seven countries: a comparison of data from national health examination surveys. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;89(3):161-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Corkey BE. Diabetes: have we got it all wrong? Insulin hypersecretion and food additives: cause of obesity and diabetes? Diabetes Care. 2012;35(12):2432-2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kolb H, Mandrup-Poulsen T. The global diabetes epidemic as a consequence of lifestyle-induced low-grade inflammation. Diabetologia. 2010;53(1):10-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zimmet P, Alberti KGMM, Shaw J. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature. 2001;414(6865):782-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lindgren P, Lindström J, Tuomilehto J, et al. Lifestyle intervention to prevent diabetes in men and women with impaired glucose tolerance is cost-effective. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2007;23(02):177-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McAuley KA, Williams SM, Mann JI, et al. Intensive lifestyle changes are necessary to improve insulin sensitivity: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(3):445-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pories WJ, Dohm GL. Diabetes: have we got it all wrong? Hyperinsulinism as the culprit: surgery provides the evidence. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(12):2438-2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hanefeld M, Koehler C, Fuecker K, Henkel E, Schaper F, Temelkova-Kurktschiev T. Insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity pattern is different in isolated impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose: the risk factor in impaired glucose tolerance for atherosclerosis and diabetes study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):868-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haffner SM, Stern MP, Mitchell BD, Hazuda HP, Patterson JK. Incidence of type II diabetes in Mexican Americans predicted by fasting insulin and glucose levels, obesity, and body-fat distribution. Diabetes. 1990;39(3):283-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lorenzo C, Wagenknecht LE, D’Agostino RB, Jr, Rewers MJ, Karter AJ, Haffner SM. Insulin resistance, beta-cell dysfunction, and conversion to type 2 diabetes in a multiethnic population: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(1):67-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weyer C, Bogardus C, Mott DM, Pratley RE. The natural history of insulin secretory dysfunction and insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 1999;104(6):787-794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferrannini E. Insulin resistance is central to the burden of diabetes. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1997;13(2):81-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fonseca VA. Defining and characterizing the progression of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(suppl 2):S151-S156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martin BC, Warram JH, Krolewski AS, Bergman R, Soeldner JS, Kahn CR. Role of glucose and insulin resistance in development of type 2 diabetes mellitus: results of a 25-year follow-up study. Lancet. 1992;340(8825):925-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zethelius B, Hales CN, Lithell HO, Berne C. Insulin resistance, impaired early insulin response, and insulin propeptides as predictors of the development of type 2 diabetes: a population-based, 7-year follow-up study in 70-year-old men. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(6):1433-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ingelsson E, Sundstrom J, Arnlov J, Zethelius B, Lind L. Insulin resistance and risk of congestive heart failure. JAMA. 2005;294(3):334-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hanley AJ, Williams K, Gonzalez C, et al. Prediction of type 2 diabetes using simple measures of insulin resistance: combined results from the San Antonio Heart Study, the Mexico City Diabetes Study, and the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes. 2003;52(2):463-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Quon M, Cochran C, Taylor S, Eastman R. Non-insulin-mediated glucose disappearance in subjects with IDDM. Discordance between experimental results and minimal model analysis. Diabetes. 1994;43:890-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lotz TF, Chase JG, McAuley KA, et al. Design and clinical pilot testing of the model-based Dynamic Insulin Sensitivity and Secretion Test (DISST). J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4(6):1408-1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McAuley KA, Berkeley JE, Docherty PD, et al. The dynamic insulin sensitivity and secretion test—a novel measure of insulin sensitivity. Metabolism. 2011;60(12):1748-1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McAuley KA, Mann JI, Chase JG, Lotz TF, Shaw GM. Point: HOMA—satisfactory for the time being: HOMA: the best bet for the simple determination of insulin sensitivity, until something better comes along. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(9):2411-2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Docherty PD, Berkeley JE, Lotz TF, et al. Clinical validation of the quick dynamic insulin sensitivity test. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2012;60(5):1266-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Docherty PD, Chase JG, Lotz T, et al. DISTq: An iterative analysis of glucose data for low-cost real-time and accurate estimation of insulin sensitivity. Open Med Inform J. 2009;3:65-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Docherty PD, Chase JG, Lotz TF, et al. A spectrum of dynamic insulin sensitivity test protocols. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2011;5(6):1499-1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Te Morenga L, Williams SM, Brown R, Mann JI. Effect of a relatively high protein, high fiber diet on body composition and metabolic risk factors in overweight women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64(11):1323-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lotz T, Chase J, McAuley K, et al. Monte Carlo analysis of a new model-based method for insulin sensitivity testing. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2008;89:215-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Docherty PD, Chase JG, David T. Characterisation of the iterative integral parameter identification method. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2012;50(2):127-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lotz TF, Goltenbolt U, Chase JG, Docherty PD, Hann CE. A minimal C-peptide sampling method to capture peak and total prehepatic insulin secretion in model-based experimental insulin sensitivity studies. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3(4):875-886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Meier JJ, Veldhuis JD, Butler PC. Pulsatile insulin secretion dictates systemic insulin delivery by regulating hepatic insulin extraction in humans. Diabetes. 2005;54(6):1649-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Toffolo G, Campioni M, Basu R, Rizza RA, Cobelli C. A minimal model of insulin secretion and kinetics to assess hepatic insulin extraction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290(1):E169-E176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Van Cauter E, Mestrez F, Sturis J, Polonsky KS. Estimation of insulin secretion rates from C-peptide levels. Comparison of individual and standard kinetic parameters for C-peptide clearance. Diabetes. 1992;41(3):368-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. ADA. Summary of revisions for the 2010 clinical practice recommendations. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(suppl 1):S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pacini G, Mari A. Methods for clinical assessment of insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;17(3):305-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mari A, Tura A, Pacini G, Kautzky-Willer A, Ferrannini E. Relationships between insulin secretion after intravenous and oral glucose administration in subjects with glucose tolerance ranging from normal to overt diabetes. Diabetes Med. 2008;25(6):671-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ahrén B, Pacini G. Islet adaptation to insulin resistance: mechanisms and implications for intervention. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2005;7(1):2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pratley RE, Weyer C. The role of impaired early insulin secretion in the pathogenesis of type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2001;44(8):929-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Docherty PD, Chase JG, Lotz TF, et al. Independent cohort cross-validation of the real-time DISTq estimation of insulin sensitivity. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2011;102(2):94-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ferrannini E, Mari A. Beta cell function and its relation to insulin action in humans: a critical appraisal. Diabetologia. 2004;47(5):943-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Boyko EJ, Fujimoto WY, Leonetti DL, Newell-Morris L. Visceral adiposity and risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study among Japanese Americans. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(4):465-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Toschi E, Camastra S, Sironi AM, et al. Effect of acute hyperglycemia on insulin secretion in humans. Diabetes. 2002;51(suppl 1):S130-S133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Black PH. The inflammatory consequences of psychologic stress: relationship to insulin resistance, obesity, atherosclerosis and diabetes mellitus, type II. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67(4):879-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. DeFronzo RA, Ferrannini E. Insulin resistance. A multifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care. 1991;14(3):173-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nathan DM, Kuenen J, Borg R, Zheng H, Schoenfeld D, Heine RJ. Translating the A1C assay into estimated average glucose values. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(8):1473-1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]