Abstract

Background: World Health Organization (WHO) defines three goals to assess the performance of a health system: the state of health, fairness in financial contribution and responsiveness. We assessed the responsiveness of health system for patients with diabetes in a defined population cohort in Tehran, Iran.

Methods: Total responsiveness and eight domains (prompt attention, dignity, communication, autonomy, confidentiality, choice, basic amenities and discrimination) were assessed in 150 patients with diabetes as a representative sample from the Tehran Glucose and Lipid Study (TLGS) population cohort. We used the WHO questionnaire and methods for analysis of responsiveness.

Results: With respect to outpatient services, 67% (n=100) were classified as Good for total responsiveness. The best and the worse performing results were related to information confidentiality (84% good responsiveness) and autonomy (51% good responsiveness), respectively. About 61% chose "communication" as the most important domain of responsiveness; it was on the 4th rank of performance. The proportions of poor responsiveness were higher in women, individuals with lower income, lower level of education, and longer history of diabetes. "Discrimination" was considered discrimination as the cause of inappropriate services by 15%, and 29% had limited access to services because of financial unaffordability.

Conclusion: Health system responsiveness is not appropriate for diabetic patients. Improvement of responsiveness needs comprehensive planning to improve attitudes of healthcare providers and system behavior. Activities should be prioritized through considering weaker domains of performance and more important domains from the patients’ perspective.

Keywords: Responsiveness, Delivery of healthcare, Patient satisfaction, Diabetes mellitus, Iran

Introduction

The definition of health offered by the world health organization (WHO) encompasses total physical, psychological and social well-being. Accordingly, the health system must pay attention to the factors impacting well-being besides mere medical needs (1,2). Thus, not only the doctor-patient relationship, but also the interaction between the health system and the individual is important.

Receiving services, as well as the atmosphere and environment in which s/he gets the services, is of utmost importance. Besides the maintenance and promotion of healthy standards, users of the health system expect to enjoy respect and dignity, more partnership in decision making for self-care, as well as a clear and assured relation regarding the confidentiality of medical information. Additionally, some other expectations including immediate attention, access to social support, the right to choose service-provider and the primary well-being possibilities are notable (3). An important achievement in 1980s’ quality care discussions was that the satisfaction of the patient from the medical care provided should be considered; though the satisfaction is also influenced by the understanding a patient develops from the health system and particularly his/her expectations of it (1-4).

In the year 2000, WHO called this concept as responsiveness, and considered it as an inherent goal for the evaluation of health systems, besides the state of health and fairness in financial contribution for health (1-4). It is also known as "patient experience" in the literature (4). In fact, the health system responsiveness finds and detects what is happening now in the health system (5,6). Health system responsiveness includes 8 operational domains; prompt attention, dignity, communication, autonomy, information confidentiality, choice, quality of basic amenities and social support (7).

Although responsiveness by itself is important as an intrinsic goal, a responsive system also encourages individuals to take care, lets them interact better with health care providers and enables better health information communication to the patient; thus enhances the health status (2-4). Interpersonal aspects of service quality could also affect utilization and the effectiveness of interventions in the health (8).

Similar to many countries, achieving adequate responsiveness remains a challenge for Iran's health system. In WHR 2000, Iran health system ranked 100 in terms of responsiveness, which indicated an urgent need for special attention to healthcare responsiveness (9).

In the year 2002, the evidence and information for policy (EPI) section performed a study on 17 countries including Iran (Multi-Country Survey Study or MCSS) to evaluate the level and distribution of health and responsiveness to assess the health system performance of the selected countries. The compared countries were mostly European and American and mainly among developed states. In the Asian continent, it was only Iran that was subjected to this comparative study. The mentioned countries also included the USA, Canada, UK, and Finland (10).

Due to the importance of responsiveness, we decided to study this factor in diabetic patients (11). The reason for focusing on diabetes is the high economic, social and individual costs and the burden of this disease on patients as well as the existing preventive capacity for the disease at all levels (11). Due to the complexity of caring the diabetic patients, many studies have been carried out to determine its cause and obstacles affecting the quality of care for this disease (12). Such a research was carried out in a mental health care center in Germany (13). Another study on older adults in South Africa assessed diabetic patients’ experiences and the health system responsiveness (14). In Iran, a case study was performed on health system responsiveness in general hospitals (15).

In this survey, responsiveness was assessed in two service sectors: outpatient and inpatient care of diabetics according to the WHO guidelines in the MCSS to answer the following key questions (5):

- The best and worst performances belong to which domains?

- How is the level and degree of perception from responsiveness among the socio–demographic groups, particularly the vulnerable groups?

- What are the most important responsiveness domains from the point of view of the respondents and what was the degree of its performance?

- To what degree are the financial barriers and discrimination responsible for not having access to the health and treatment services?

Methods

This research carried out on subcohort of residents of the 13th district of Tehran metropolitan with diabetes mellitus, who were under the coverage of Tehran lipid and glucose study (TLGS) since 1998. TLGS is an extended epidemiologic and prospective cohort study with the goal of estimating the level of metabolic disorders and their risk factors and testing population interventions for prevention and control of these disorders. The research has been carried out in the framework of a national research project of the country's research council since the year 1377 AH (1998) (16). Among inhabitants of the 13th district of Tehran, a group of 15000 persons were selected randomly and investigated and screened periodically every 2.5 years, observing the time priority.

- The population of this cross-sectional study included diabetic patients over 18 years of age, confirmed in TLGS, who did not belong to intervention group of TLGS (and did not receive any special care more than routine services available for general population) and were able to speak and listen. A sample of 150 diabetic persons was chosen with the simple random method and studied concurrently with their planned round of workup (in TLGS).

- We used the WHO standard questionnaire for responsiveness to collect data (17). This questionnaire was validated and used in 1380 AH (2000-2001) during the MCSS study for assessing the responsiveness of health system in Iran (10). The questionnaire is comprised of three parts for the social background (record), responsiveness of the health system and health system enjoyment. The health system responsiveness questions in its different domains were designed to assess the experience of individuals with respect to outpatient services, care at home and inpatient services during the last 12 months. The offered service could have started from the doctor's office or infirmary, a hospital or a center offering health and treatment service or during a home call by a health service worker. The health system responsiveness questions are designed for eight domains of responsiveness and items.

- Face to face interview was performed by a trained interviewer. A brief standard explanation was given on the study and goals of the project as well as on its social and moral benefits. The subject's consent was obtained before the interview.

- The inputted data were analyzed using the SPSS v. 16 software. We also used the STATA10 do-files of MCSS which had been designed by WHO (18). All figures and tables were prepared by Microsoft excel.

Each domain was either assessed as "good responsiveness" (for good or very good choices) or "responsiveness as poor" (for very bad, bad and average choices). This analysis was performed both for outpatient and inpatient services and the total responsiveness was calculated from the average responsiveness of the areas in two parts.

The study was approved both by the research council of Iran University of Medical Sciences (and its committee on research ethics) and the Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Results

The sample included 97 women (65%) and 53 men (35%) with a mean (±SD) age of 59 (±9.2) years (Range: 31-86 years). Among total 150 patients, 148 individuals (99%) had received outpatient services during the past 12 months while just 12% had received inpatient services; around 1.3% had not received any inpatient or outpatient service. The last healthcare visit was done during the past 30 days in 54% (n=81), between 1 to 3 month in 22% (n=33), between 3 to 6 month in 13% (n=20) and between 6 to 12 months in the rest of patients.

Responsiveness in the Outpatient Care Services

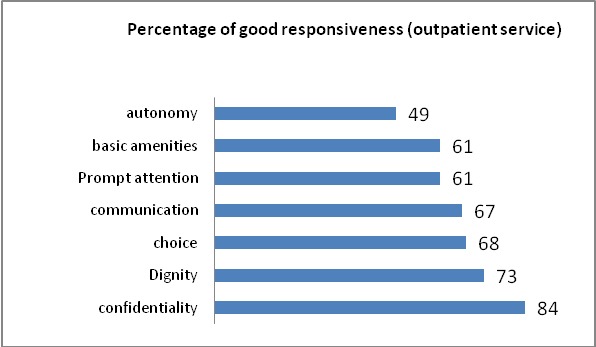

The level and degree of good responsiveness in this part was reported as 67%. Fig. 1 shows the responsiveness in different domains. The performance was better for the domains of confidentiality (84%) and dignity (73%). The patients’ reported lowest percentage of good responsiveness was for the domain of autonomy (49%).

Fig. 1 .

Percentage rating good responsiveness in different domains (outpatient service)

Women's perception of poor responsiveness was lower than men (28% vs 38%). Individuals with lower incomes (first and second quintiles) showed lower perception of responsiveness (64.5%) compared to higher-income groups (69%). With increasing age, the perception of "responsiveness as poor" decreased while the highest such proportion was reported by the youngest age group (Table 1).

Table 1 . Percentage rating outpatient service responsiveness as poor in subgroups .

| Characteristic | Categories | Number |

| Sex | Female | 27 (28%) |

| Male | 20 (38%) | |

|

Age group (years) |

30-44 | 6 (41%) |

| 45-59 | 21 (33%) | |

| 60-69 | 12 (30%) | |

| 70 or more | 9 (31%) | |

| Disease duration (years) | 0-4 | 16 (39%) |

| 5-9 | 9 (27%) | |

| 10-14 | 14 (36%) | |

| 15 or more | 8 (27%) | |

| Income quintile | First | 6 (30%) |

| Second | 9 (41%) | |

| Third | 5 (27%) | |

| Fourth | 6 (29%) | |

| Fifth | 7 (37%) | |

| Education | No Education | 8 (33%) |

| Primary | 10 (32%) | |

| secondary | 17 (36%) | |

| Higher Education | 14 (30%) | |

| Overall | 49 (33%) |

The levels of "responsiveness as poor" in different domains and their subdomains different domains and their subdomains were estimated by age group, sex, level of education, level of income and the duration of diabetes; domains with the best and worst performances were specified in each sub-group (Table 2).

Table 2 . Patient assessed responsiveness of ambulatory care services: percentage reporting “Moderate”, ”Bad” or ”Very Bad” .

| Prompt Attention | Dignity | Communication | Autonomy | ||||||||||

| Category | Timely care | Overall | Respectful treatment by health care staff | Respectful treatment by office staff | Respect for privacy during physical exams | Overall | Attentiveness of health care staff | Clarity of explanations by health care providers | Time to ask questions | Overall | Involvement in decision- making | Permission sought before testing/treating | Overall |

| Sex | |||||||||||||

| Female | 23 | 38 | 6 | 14 | 10 | 27 | 15 | 26 | 26 | 36 | 55 | 64 | 53 |

| Male | 25 | 43 | 6 | 14 | 14 | 27 | 14 | 20 | 25 | 27 | 49 | 57 | 47 |

| Age Group (years) | |||||||||||||

| 30-44 | 33 | 40 | 0 | 13 | 27 | 33 | 13 | 13 | 27 | 27 | 60 | 67 | 53 |

| 45-59 | 19 | 34 | 6 | 14 | 9 | 27 | 13 | 14 | 22 | 27 | 48 | 61 | 44 |

| 60-69 | 23 | 46 | 10 | 13 | 10 | 28 | 18 | 36 | 38 | 49 | 56 | 69 | 62 |

| 70 or more | 31 | 41 | 4 | 14 | 10 | 24 | 14 | 35 | 17 | 31 | 56 | 48 | 52 |

| Quintiles of income | |||||||||||||

| Q1 (Poorest) | 10 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 25 | 60 | 55 | 45 |

| Q2 | 40 | 35 | 15 | 20 | 20 | 40 | 15 | 20 | 45 | 35 | 45 | 85 | 75 |

| Q3 | 15 | 30 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 35 | 40 | 45 | 35 |

| Q4 | 21 | 47 | 0 | 21 | 11 | 21 | 11 | 32 | 11 | 21 | 32 | 58 | 42 |

| Q5 (Richest) | 25 | 55 | 5 | 20 | 5 | 35 | 10 | 20 | 25 | 25 | 65 | 45 | 45 |

| Education | |||||||||||||

| No Education | 8 | 38 | 8 | 8 | 13 | 21 | 13 | 17 | 25 | 25 | 46 | 67 | 58 |

| Primary (<5y) | 33 | 43 | 10 | 20 | 17 | 37 | 20 | 47 | 37 | 53 | 57 | 57 | 57 |

| Secondary (6-11y) | 25 | 38 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 15 | 10 | 8 | 17 | 25 | 60 | 65 | 50 |

| Higher (+12y) | 24 | 40 | 2 | 16 | 11 | 38 | 16 | 29 | 29 | 33 | 47 | 58 | 44 |

| Duration of Disease(year) | |||||||||||||

| 0-4 | 31 | 43 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 19 | 14 | 17 | 24 | 24 | 54 | 64 | 46 |

| 5-9 | 14 | 23 | 3 | 11 | 9 | 29 | 14 | 11 | 23 | 26 | 56 | 51 | 51 |

| 10-14 | 23 | 46 | 5 | 15 | 13 | 41 | 15 | 39 | 28 | 44 | 57 | 69 | 56 |

| 15 or more | 27 | 47 | 7 | 17 | 13 | 20 | 13 | 27 | 30 | 43 | 60 | 57 | 53 |

| Total | 24 | 39 | 6 | 14 | 12 | 27 | 14 | 24 | 26 | 33 | 57 | 61 | 51 |

| Confidentiality | Choice | Basic amenities | Discrimination* | Total Respondents | |||||||||

| Category | Respect for privacy during consultations |

Keeping personal information confidential |

Overall | Ease of getting to healthcare provider of choice |

Ease of getting to other healthcare services |

Overall | Quality of waiting room | Cleanliness | Overall | Discrimination | Discrimination against women | ||

| Sex | |||||||||||||

| Female | 7 | 2 | 11 | 18 | 11 | 28 | 29 | 26 | 33 | 9 | 4 | 96 | |

| Male | 14 | 12 | 24 | 14 | 10 | 41 | 51 | 35 | 51 | 2 | 2 | 51 | |

| Age Group (years) | |||||||||||||

| 30-44 | 13 | 7 | 20 | 33 | 13 | 47 | 53 | 40 | 40 | 13 | 20 | 15 | |

| 45-59 | 13 | 5 | 19 | 13 | 9 | 27 | 36 | 31 | 42 | 5 | 0 | 64 | |

| 60-69 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 18 | 13 | 36 | 38 | 28 | 38 | 8 | 5 | 39 | |

| 70 or more | 7 | 4 | 18 | 14 | 10 | 34 | 28 | 20 | 34 | 7 | 0 | 29 | |

| Quintiles of income | |||||||||||||

| Q1 (Poorest) | 0 | 5 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 35 | 30 | 45 | 50 | 5 | 5 | 20 | |

| Q2 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 35 | 10 | 45 | 40 | 25 | 45 | 10 | 5 | 20 | |

| Q3 | 15 | 5 | 20 | 5 | 5 | 30 | 25 | 20 | 25 | 5 | 0 | 20 | |

| Q4 | 5 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 21 | 47 | 26 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 19 | |

| Q5 (Richest) | 15 | 10 | 25 | 10 | 10 | 30 | 45 | 35 | 45 | 0 | 5 | 20 | |

| Education | |||||||||||||

| No Education | 21 | 8 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 25 | 33 | 25 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 24 | |

| Primary (<5y) | 13 | 3 | 20 | 20 | 17 | 47 | 47 | 40 | 57 | 10 | 0 | 30 | |

| Secondary (6-11y) | 4 | 6 | 15 | 15 | 6 | 27 | 38 | 29 | 38 | 10 | 8 | 48 | |

| Higher (+12y) | 7 | 4 | 16 | 18 | 11 | 33 | 31 | 24 | 29 | 4 | 2 | 45 | |

| Duration of Disease(year) | |||||||||||||

| 0-4 | 12 | 2 | 19 | 19 | 29 | 45 | 48 | 36 | 52 | 19 | 5 | 42 | |

| 5-9 | 6 | 6 | 18 | 6 | 6 | 26 | 26 | 31 | 37 | 11 | 3 | 35 | |

| 10-14 | 13 | 8 | 15 | 21 | 21 | 31 | 36 | 26 | 33 | 13 | 8 | 39 | |

| 15 or more | 7 | 7 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 27 | 37 | 23 | 33 | 13 | 4 | 30 | |

| Total | 10 | 5 | 16 | 16 | 19 | 32 | 36 | 29 | 39 | 15 | 5 | 148 | |

*percentage of perceived discrimination among total respondents

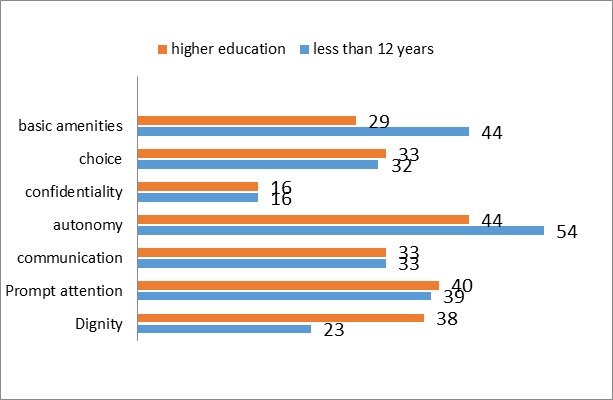

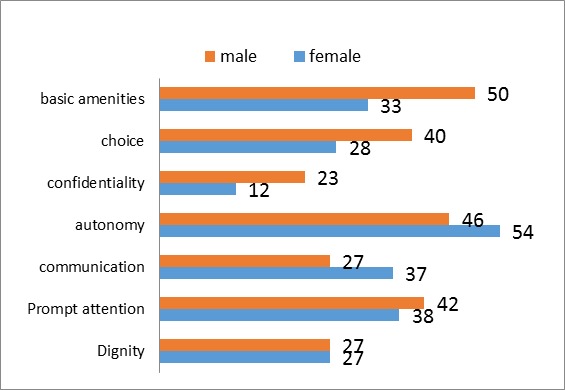

Women and under 12 years education group reported a higher percentage of 'responsiveness as poor" in all except two domains (Figs. 2 &3). About %84 of subjects had experienced diagnostic tests during the assessment period; In %7, tests were done on the same day while %38 waited 3-5 days, %46 between 6 to10 days and %50 of cases 6 days or more for doing.

Fig. 3 .

Percentage rating ambulatory care responsiveness as poor, by education level

Fig. 2 .

Percentage rating ambulatory care responsiveness as poor, by sex

Inpatient Care Responsiveness

Only 12% (n=18) had experienced inpatient care. They reported the level of good responsiveness as %67 (n=12) and the best and worst performances were reported for the domains of dignity (83%, n=15) and autonomy (53%, n=10) respectively. Overall Responsiveness of Health System

The level of good responsiveness for the combination of inpatient and outpatient services was 66%. That was 85% for the domain of confidentiality (the best performance), 78% for social support, 76% for dignity, 70% for communication, 68% for choice, 63% for prompt attention, 63% for quality of basic amenities and 52% for the domain of autonomy (the lowest performance).

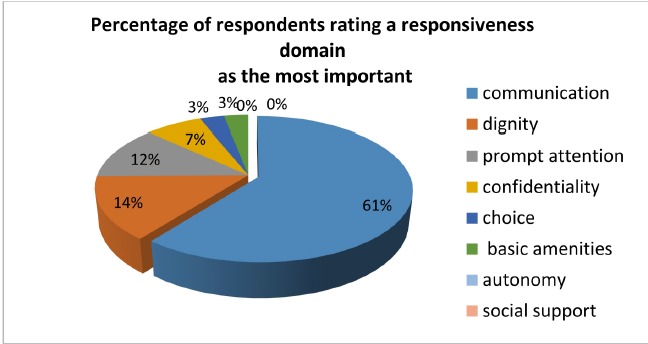

The Most Important Domain

The most important domain of responsiveness from the patients' point of view was "communication". Sixty-one percent of subjects chose communication as the most important domain (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 .

Percentage of respondents rating a responsiveness domain as the most important

Among female and male responders, 65% and 47% considered communication as the most important domain, respectively. The groups with lower education and older age groups also selected this domain more than other respondents (Table 3).

Table 3 . Population of the relative importance of responsiveness domains: percentage reporting domain to be the “Most Important” .

| Category | Prompt Attention | Dignity | Communication | Autonomy | Confidentiality | Choice | Basic Amenities | Social Support | Total Respondents |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 10 | 10 | 66* | 1 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 97 |

| Male | 16 | 20 | 49* | 2 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 52 |

| Age Group (years) | |||||||||

| 30-44 | 40* | 13 | 13 | 0 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| 45-59 | 6 | 13 | 66* | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 64 |

| 60-69 | 15 | 10 | 62* | 0 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 40 |

| 70 or more | 7 | 21 | 69* | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 30 |

| Quintiles of income | |||||||||

| Q1 (Poorest) | 5 | 20 | 65* | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| Q2 | 5 | 15 | 65* | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 |

| Q3 | 10 | 20 | 60* | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| Q4 | 11 | 0 | 74* | 5 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 20 |

| Q5 (Richest) | 25 | 5 | 40* | 0 | 10 | 15 | 5 | 0 | 20 |

| Education | |||||||||

| No Education | 8 | 21 | 67* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 24 |

| Primary (<5y) | 13 | 7 | 70* | 0 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 30 |

| Secondary (6-11y) | 8 | 15 | 54* | 2 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 48 |

| Higher (+12y) | 18 | 13 | 56* | 2 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 47 |

| Duration of Disease(year) | |||||||||

| 0-4 | 12 | 19 | 52* | 2 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 42 |

| 5-9 | 6 | 17 | 57* | 0 | 11 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 35 |

| 10-14 | 13 | 8 | 64* | 3 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 39 |

| 15 or more | 20 | 10 | 67* | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 30 |

| Total | 12 | 14 | 59* | 1 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 148 |

*Most important domain in the subgroup

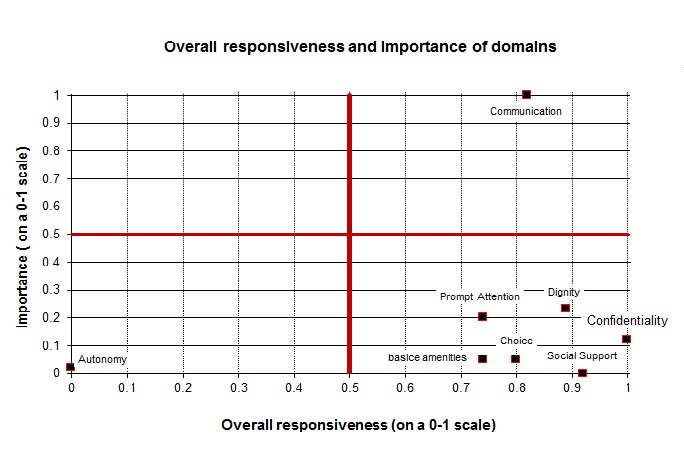

Figure 5 demonstrates the relationship between important domains from the respondents' point of view and the performance of health system for each domain in a 0-1 scale. Communication, as the most important domain for responders, got the 4th rank according to performance of health system.

Fig. 5 .

Overall responsiveness and importance domains

Financial Barrier and Discrimination

Around 24% (n=35) of the respondents stated that they had not sought for health care services due to affordability issues, and 27% (n=40) refrained and refused health care for the same reason. Refusal to seek care due to unaffordability was four times higher among women than men. It was 32% in the group with education lower than 12 years, compared to 23% in higher educational levels (Table 4). This percentage in the higher three quintiles of income was three times less than the poorest two quintiles.

Table 4 . Self-reported utilization of health services and unmet need in the previous 12 months .

| Percentage of patients reported utilization or unmet need during past 12 months | Average number of visits to provider/facility in the previous 12 months | |||||||||||

| Ambulatory Care | Home Care | Hospital Inpatient Care | Non Use | Refused care due to unaffordability | Did not seek care due to unaffordability | General practitioner | Hospital Ambulatory | Hospital Inpatient | Pharmacy | Other* | Total Respondents | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 99 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 36 | 40 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 97 |

| Male | 98 | 0 | 12 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 52 |

| Age Group (years) | ||||||||||||

| 30-44 | 100 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 33 | 40 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 15 |

| 45-59 | 100 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 27 | 27 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 64 |

| 60-69 | 98 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 30 | 35 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 40 |

| 70 or more | 96 | 0 | 23 | 4 | 20 | 23 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 28 |

| Quintiles of income | ||||||||||||

| Q1 (Poorest) | 100 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 20 |

| Q2 | 95 | 0 | 14 | 5 | 38 | 38 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 21 |

| Q3 | 100 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 20 |

| Q4 | 95 | 0 | 20 | 5 | 20 | 15 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 20 |

| Q5 (Richest) | 100 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 20 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| No Education | 100 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 21 | 21 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 24 |

| Primary (<5y) | 100 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 33 | 33 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 30 |

| Secondary (6-11y) | 100 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 29 | 38 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 48 |

| Higher (+12y) | 96 | 0 | 11 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 47 |

| Duration of Disease(year) | ||||||||||||

| 0-4 | 98 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 21 | 21 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 43 |

| 4-9 | 100 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 29 | 31 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 35 |

| 10-14 | 98 | 0 | 18 | 3 | 33 | 38 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 40 |

| 15 or more | 100 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 28 | 27 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 30 |

| Total | 99 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 27 | 29 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 148 |

*Other: dentist-specialist-traditional healer-clinic-home health care service

Utilization of Service Units

In this study, the level of benefiting from the health services during the last 12 months reached 99%. In the last 30 days, this level was 62%, and the average number of outpatient visits was two times. Table 4 demonstrates average times of visiting the health care providers in different sub-groups. The percentage of utilizing the inpatient services was higher in patients with older age and longer length of diabetes.

Discussion

In this study, we estimated degree and level of responsiveness of the health system with respect to the diabetics under the scrutiny of TLGS study project. We chose the chronic disease of diabetic because of the high prevalence of this problem and its wide spectrum of side effects which requires integration with the health system and its sources for the sake of promoting health and life quality.

We used a sub-sample of diabetic patients from a population cohort in Iran. The average age of patients in our study was 59 years with a minimum age of 31 which is not far from the population-based studies in Isfahan and Tehran. Most of our patients were woman; this finding is compatible with the higher prevalence of diabetes in women than men in Iran (19). Our study emphasized the importance of communication domain from the perspective of patients; the best performance was observed in confidentiality.

WHO carried out MCSS in 2001 in 17 countries including Iran? The MCSS study results in Iran was reported separately (18,20).

Due to the small number of the individuals who reported inpatient services (18 persons), we did not compare responsiveness based on outpatient and inpatient services.

In this study, the best performance in the outpatient section was reported in the confidentiality domain with (84%). MCSS reported the same domain as the best domain of performance for the general health system in Iran by 85% of respondents (18). In both studies, dignity was the second rank of performance; however, its performance was weaker in the current study than MCSS (73% vs. 81%). In the present study, good performance on communication was reported by 67% (the 4th rank of domains) compared to 73% in MCSS (the 3rd rank).

Although the best performance in responsiveness domains was related to confidentiality, in the MCSS study, rank of Iran in this domain was 13th among the 17 countries studied. Confidentiality score of England (first rank) was 96% compared to 81% in Iran (10).

In a study on mental health care in Germany, the best performance was related to confidentiality domain with 90% reported good performance (13). Confidentiality and Dignity showed the best performance in a study on older adults in South Africa (14).

The worst performance in the outpatient services in our study was related to autonomy domain, with "responsiveness as poor" assessment of 51%. In the MCSS, the same domain was the worst with a 38% reported poor responsiveness.

Distribution of responsiveness and presence of systematic differences between different subgroups of population are other important aspects of assessment of health system responsiveness. It is important to know whether perceived responsiveness is different between women, older people (60 year and more), people with lesser incomes (lower two quintiles), individuals with lower education (under 12 years), people with bad health conditions (in their self-assessment) with respect to others or not.

In this study, women reported better responsiveness compared to men, and individuals with older age, less education and lower income reported worse responsiveness than other subgroups. It was reported in MCSS study that individuals with a poor perceived health report worse responsiveness. We used disease duration as a surrogate of health condition, but we did not observe a specific pattern of different responsiveness based on this factor.

All domains of responsiveness are important, and specifying a domain as the most important one does not degrade others, however it can help policy makers and health managers for prioritizing interventions to improve health system responsiveness.

The communication domain was reported as the most important domain by respondents (61%). This was a consistent observation in almost all the population subgroups. The weakest performance was autonomy in this study, which was also the last rank of importance. This might be a cultural aspect of Iranian behavior who delegates most of the important decisions to health care providers.

In the health system of Iran based on the MCSS study, the most important domain was prompt attention (selected by 31% of respondents) and the domains of dignity (21%), communication (16%), confidentiality (13%), basic amenities’ quality (8%), the right of choice (5%), autonomy (3%) and social support (3%) were reported as important less frequently (18). Also, in another study in patients with chronic heart failure in Tehran (Iran), prompt attention and dignity were selected as the most important domains. (21) In the MCSS study, prompt attention was reported as the most important domain of responsiveness in general (all countries) (22). We do not know why the result is different with other studies, but chronic nature of diabetes might be a reason for their preference in choosing communication as the most important domain. This disorder needs a set of complicated services for these patients, of which the manner for establishing communication for presenting such services is more important than the speed of attention in submitting them. Transparency in communication means that the provider of services must listen carefully to the concerns of the patients and give a clear explanation regarding their side effects or that of complications related to it. The explanations must be comprehensible and prepare the ground for more questions. This will lead to more understanding of the sickness for the patient and consequently better management of it. It is worth mentioning that the most weakness is related to the two last concepts, namely comprehensible explanations and opportunity for forwarding the reported question which confirms the probability mentioned above.

Improving the communication establishment field does not need a lot of investment, and only a change of attitude by the health care personal through using such procedures as training and health care methods could achieve this task with less investment, contrary to the internet goal of health keeping which needs expensive technology and specialists to keep health conditions promoted.

After passing a decade from the MCSS study at the public health level of Iran, a better performance of responsiveness in this study was expected. This might be related to two different factors; the health system responsiveness has not improved or, a more uniform distribution of the chronic health condition in the participants of this study influenced the results (and this does not represent representative of health system). Individuals with a poor health condition (in their self-assessment) usually have a worse perception of the responsiveness performance (17). Also, in this study, there were more women and women had a different perception of performance.

Conclusion

Critical analysis of the results of health system responsiveness could greatly contribute to the improvement and promotion of health system practical policies.

The purpose of this study was to present health system responsiveness with respect to the diabetic patients. We recommend paying attention to each domain of responsiveness, especially communication as the most important domain, both in all clinical settings and in the national comprehensive program for control and prevention of diabetes.

Although the study was limited to individuals with diabetes, it is a reflection of general responsiveness of health system; considering the relative importance and performance of different domains of responsiveness are helpful for planning health services, especially for chronic diseases.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the people who have collaborated in this study: Mr. K. Ahmadi, Iran's permanent representative at the UN Office in Geneva, NaidooNirmala Devi at the WHO, DrSeyyed Mohammad Sajjad, Dr Sarah Shakerian the Department of Social Medicine.

Cite this article as: Sajjadi F, Moradi-Lakeh M, Nojomi M, Baradaran HR, Azizi F. Health system responsiveness for outpatient care in people with diabetes Mellitus in Tehran. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2015 (15 November). Vol. 29:293.

References

- 1.Valentine NB, de Silva A, Kawabata K, Darby C, Murray CJ, Evans DB, et al. Health system responsiveness: concepts, domains and operationalization. Health System Performance Assessment Debates Methods Empiricism. 2003:573–96. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arokiasamy P, Guruswamy M, Roy TK, Lhungdim H, Chatterji S, Nandraj S. Health System Performance Assessment, World Health Survey, 2003, India. Mumbai, Geneva, New Delhi: International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), World Health Organization (WHO), India, WR office; 2006.

- 3. Darby C, Valentine N, Murray CJ, De Silva A. World Health Organization (WHO): strategy on measuring responsiveness (Internet). World Health Organization; 2000. Available from: http://www.who.int/entity/healthinfo/paper23.pdf, Accessed by 2/25/2015.

- 4. Gostin L, Valentine N, Hodge JrJG. The domains of health responsiveness–a human rights analysis.2003 Available from: http://www.who.int/entity/hhr/information/en/Series_2%20Domains%20of%20health%20responsiveness.pdf,Accessed by 2/25/2015.

- 5. World Health Organization: The Health Systems Responsiveness Analytical Guidelines for Surveys in the Multi-country Survey Study, WHO, 2005; 9-54.

- 6.Murray CJ, Kawabata K, Valentine N. People’s experience versus people’s expectations. Health Aff(Millwood) 2001;20(3):21–4. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. De Silva A, Valentine N. Measuring responsiveness: results of a key informants’ survey in 35 countries (Internet). World Health Organization; 2000. Available from: http://www.who.int/entity/responsiveness/papers/paper21.pdf?ua=1, Accessed by 2/25/2015.

- 8. Evidence and Information for Policy, Why responsiveness is important. Available from: http://www3.who.int/whosis/menu.cfm?path=hsr,Accessed by 7/15/2008.

- 9.Rashidian A, Kavosi Z, Majdzadeh R, Pourreza A, Pourmalek F, Arab M. et al. Assessing health system responsiveness: a household survey in 17th District of Tehran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2011;13(5):302–308. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Naghavi M, Jamshidi H. Utilization of health services in the Islamic Republic of Iran (2002) (Internet). Tehran, Iran: Ministry of health and medical education; 2004 (cited 2015 Feb 24). Available from: http://behdasht.gov.ir/uploads/1-9.

- 11. Delavari A, MahdaviHazave A, NorouziNejad A, Yarahmadi SH.The doctor and diabetes (national program on prevention and control of diabetes).3rd ed. Publication center of Seda.Tehran, 2005.

- 12.Alberti H, Boudriga N, Nabli M. Primary care management of diabetes in a low/middle income country: A multi-method, qualitative study of barriers and facilitators to care. BMC FamPract. 2007;8(1):63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bramesfeld A, Wedegärtner F, Elgeti H, Bisson S. How does mental health care perform in respect to service users’ expectations? Evaluating inpatient and outpatient care in Germany with the WHO responsiveness concept. BMC Health Serv Res 2007 Jul. 2;7(1):99. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peltzer K, Phaswana-Mafuya N. Patient experiences and health system responsiveness among older adults in South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2012;5:18545. doi: 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebrahimipour H, Najjar AV, Jahani AK, Pourtaleb A, Javadi M, Rezazadeh A. et al. Health system responsiveness: a case study of general hospitals in Iran. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2013;1(1):85. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2013.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azizi F, Rahmani M, Emami H, Mirmiran P, Hajipour R, Madjid M. et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in an Iranian urban population: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (Phase 1) Soz- Präventivmedizin 2002 Dec. 1;47(6):408–26. doi: 10.1007/s000380200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Valentine NB, Lavallée R, Liu B, Bonsel GJ, Murray CJL. Classical Psychometric Assessment of the Responsiveness Instrument in the WHO Multi-country Survey Study on Health and Responsiveness 2000–2001. In Health Systems Performance Assessment: Debates, methods and Empiricism. Ed, Christopher J. L. Murray, David B. Evans, WHO 2001:616-20.

- 18. Prasad A, Valentine NB, Vega J. Iran Health System Responsiveness: the Multi-Country Survey Study, 2000-2001. Country Analysis and Report Series on Household Surveys of Health System Responsiveness.WHO Equity Team, Evidence and Information for Policy, 2006.

- 19. Alavi M, Ghotbi M. Comprehensive program to prevent and control type 2 diabetes - Phase (2) 2009. 1st ed. Sepidbarg press, Tehran, 2012.

- 20. De Silva A. A framework for measuring responsiveness (Internet).World Health Organization Geneva; 2000. Available from: http://wwwlive.who.int/entity/healthinfo/paper32.pdf, Accessed by 2/25/2015.

- 21.Karami-Tanha F, Moradi-Lakeh M, Fallah-Abadi H, Nojomi M. Health system responsiveness for care of patients with heart failure: evidence form a university hospital. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(11):736–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valentine NB, Salomon JA, Murray CJL, Evans DB, Murray CJL, Evans DB. Weights for responsiveness domains: analysis of country variation in 65 national sample surveys. Murray CJL Evans DB Health System Performance Assessment Debates Methods Empiricism Geneva World Health Organ. 2003:631–52. [Google Scholar]