Abstract

Objective

The stress hormone cortisol exhibits a diurnal rhythm throughout the day, as well as within person variability. Recent statistical approaches allow for the estimation of intraindividual cortisol variability (“ICV”) and a greater ICV has been observed in some mood disorders (major depression, remitted bipolar disorder); however, ICV has not been examined following stress management. In this secondary analyses of an efficacious randomized clinical trial, we examine how ICV may change after cognitive behavioral stress management (CBSM) among healthy stressed women at risk for breast cancer. Second, we concurrently compare other calculations of cortisol that may change following CBSM.

Methods

Multilevel modeling (MLM) was applied to estimate ICV and to test for a group by time interaction from baseline, post-intervention, to 1 month following CBSM. Forty-four women were randomized to the CBSM; 47 to the comparison group; mean age of the entire group was 44.2 (SD = 10.27).

Results

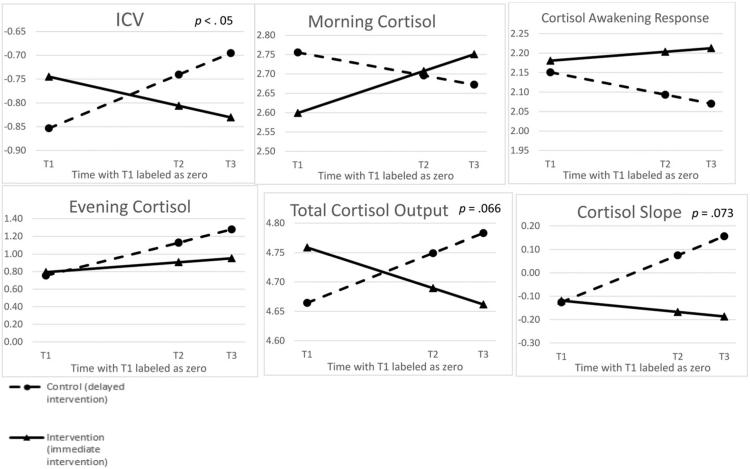

After controlling for relevant covariates, a significant time by group interaction emerged (β estimate = −.070; p < .05), such that CBSM participants demonstrated a lower ICV following CBSM compared to the comparison group. The interaction for cortisol slope and cortisol output (area under the curve) approached significance (β estimates = −.10 and −.062, respectively; p's < .08), while other cortisol outcomes tested were not significantly changed following CBSM.

Conclusion

ICV may represent a novel index of cortisol dysregulation that is impacted by CBSM and may represent a more malleable within-person calculation than other, widely applied cortisol outcomes. Future research should examine these relationships in larger samples, and examine ICV and health outcomes.

Keywords: Cortisol, Variability, Stress, Stress management, Modeling

Introduction

The stress hormone cortisol is a potent endogenous anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid produced by the adrenal cortex. Cortisol exhibits a diurnal rhythm throughout the day, with an initial rise in the morning (referred to as the “cortisol awakening response” or CAR; [39]) and an anticipated decline throughout the day. Given cortisol's role in the immune system [37], in addition to tumor biology [16,36] there is a wealth of interest in the extant literature examining relations among cortisol rhythm in cancer populations (for review see [6,13]). For example, a flatter cortisol slope (corresponding a less pronounced decline in cortisol throughout the day), maintains predictive value of decreased survival in breast cancer [33] and, most recently, in lung cancer [32]. Further, a flatter cortisol slope (thought to represent cortisol dysregulation throughout the day) is related to clinical outcomes such as fatigue in breast cancer patients [9]. However, less is known about cortisol rhythms among healthy populations, who may be at risk for cancer.

Given that cortisol is released during times of stress, there is a robust body of literature examining changes in cortisol rhythm across those experiencing disturbances in mood. For example, higher evening cortisol, resulting in a flatter cortisol slope throughout the day, has been observed in those suffering from chronic stress [1], patients with psychotic major depression [7], and depressed patients with coronary artery disease [8]. Indeed, meta-analysis confirms that depressed individuals demonstrate increased morning and evening cortisol levels [20]. In cancer populations, specifically, — a group which may be at risk for developing psychological distress [26] – cortisol rhythm is related to social isolation in breast cancer patients, such that greater cortisol output is related to those experiencing the least amount of social support [35]. In ovarian cancer, a greater difference between morning and evening cortisol values is significantly related to greater functional disability, fatigue and vegetative depression [38]. Conversely, breast cancer patients who meet criteria for PTSD or prior major depressive disorder exhibit decreased plasma cortisol [22]. Collectively, while cortisol rhythm is notably altered within psychiatric disturbances, it remains difficult to compare across studies given the many different calculations applied.

An emerging cortisol calculation that is related to a number of psychiatric conditions, yet has received less attention, is estimating the degree to which an individual's cortisol output may be erratic on a given day. Referred to as intraindividual cortisol variability (ICV, [31]), this variability estimate is similar to what has been termed beep-level variance [27], cortisol pulsatility [41] and approximate entropy in cortisol production [29]. In clinical populations, higher cortisol ICV is seen among those with remitted bipolar disorder [17] and major depressive disorder [27,29] suggesting that a more erratic cortisol rhythm is related to psychiatric disorder. These relationships were recently extended to a group of women undergoing surgery for suspected endometrial cancer, where greater depressive symptoms were related to a more erratic cortisol output [31]. It remains less clear how such relationships extend to healthy, stressed populations or how ICV is impacted by stress management intervention.

If ICV is associated with increased stress and depressive symptoms, then interventions designed to address these symptoms should improve ICV. A number of clinical trials have applied stress management in cancer populations in an effort to potentially attenuate cortisol production. For example, participation in cognitive behavioral stress management in cancer populations resulted in a decrease in afternoon cortisol levels [4,28] as well as total 24 hour urinary cortisol output [3]. These changes also parallel changes in participants’ perceived ability to relax [28]. Similarly, in breast cancer patients, supportive expressive therapy and mindfulness based cancer recovery both resulted in a more normalized cortisol slope (e.g., greater decline throughout the day) compared to controls [11]. Similar to the cross-sectional studies of mood disturbances and cortisol rhythm reviewed above, this literature is limited by the number of cortisol calculations applied, leaving unanswered questions such as which calculations are most sensitive to change and which are most relevant to health outcomes? It is therefore germane to examine multiple cortisol calculations including ICV, concurrently following participation in a stress management intervention.

Given these limitations in the current literature, the present study aimed to examine changes in cortisol rhythm among healthy stressed women at risk for breast cancer due to family history. Women were randomized to a cognitive behavioral stress management (CBSM) intervention or to a wait-list control condition. This 10-week intervention was shown to reduce perceived stress and depressive symptoms and, further, those that practiced relaxation more frequently demonstrated the greatest reductions in these parameters [25]. For the current secondary analysis, it was hypothesized that women randomized to the CBSM condition would demonstrate lower ICV immediately after the intervention and during the immediate follow-up period (1 month post-intervention). No specific hypotheses were put forth for other cortisol outcomes, given the heterogeneity of cortisol outcomes across the relevant literature reviewed above.

Methods

Study design

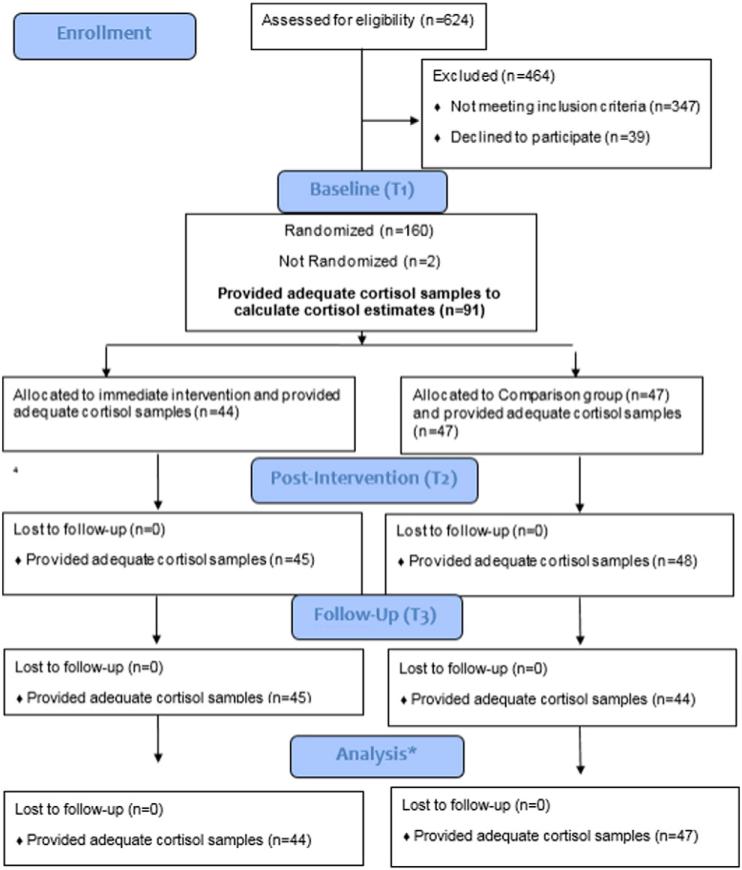

The present study is a secondary data analysis of a larger randomized controlled trial of the effects of CBSM on antibody response to vaccine among stressed women at risk for breast cancer. Eligible participants completed a baseline (T1) questionnaire and then were randomized to either CBSM or a wait-list comparison group. Outcome variables were collected at baseline (T1), immediately post-intervention or 10-week waiting period (T2), and one month (T3). While data was collected at 6 months (T4), and 7 months (T5) post-intervention, the present study examines data from only the T1, T2 and T3 time points consistent with hypotheses regarding potential effects of the intervention. Comparison group women were offered the full CBSM intervention after completing questionnaires at all time points. Participant flow through each stage of the study is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Participant flow chart. *The multilevel models applied in the current analyses accommodate missing data in longitudinal models, thus participants providing initial cortisol sample (n = 91) were included in the final analysis.

Participants

Participants were recruited from the greater Seattle area and were eligible if they were between the ages of 18–60, reported having any family history of breast cancer, had a healthy immune system, and elevated levels of distress. Participants were screened for psychological distress and women reported distress at a ½ standard deviation above the population mean for at least one of the 4-item instruments given (Perceived Stress Scale and the Breast Cancer Worry Scale). Exclusion criteria included prior diagnosis of cancer or autoimmune disease, current major depressive episode, (or other unmanaged mood disorder), history of psychotic disorder, smoking or substance dependence, consuming more than 10 drinks of alcohol a week, previous Hepatitis A diagnosis or Hepatitis A vaccination. All study procedures were approved by the Fred Hutchinson Center Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained in writing from all participants before study entry.

Intervention

Women randomized to the intervention condition were asked to attend 10, 2-hour, group CBSM sessions (4–10 women) on a weekly basis. The CBSM intervention was based on an existing intervention for women with early stage breast cancer [5]. Elements of the intervention were similar to the existing CBSM intervention and included education on awareness of the effects of stress, cognitive reframing, cognitive coping skills training, assertiveness training, anger management, and various relaxation techniques (e.g., including progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, and mindfulness meditation). All CBSM sessions were led by female licensed clinical psychologists, master-level social workers, postdoctoral fellows, or psychology interns. Adherence to the intervention protocol was ensured by the study author (BAM) reviewing recorded audio taped according to a module-specific Intervention Integrity Checklist.

Cortisol

Salivary cortisol was collected across 5 time points throughout the day (at awakening, 30 min following awakening, 11 AM, 5 PM and at bedtime, hereafter referred to as “evening”) for 2 consecutive days prior to the intervention, immediately following the 10 week intervention, and at 1 month follow-up.

Analytic Plan

The primary research question in the present analyses was whether the cognitive behavioral stress management intervention was related to changes in ICV from T1 to T3. However, as a host of calculations exist in the extant literature of cortisol rhythm and overall output [14], we included 5 cortisol output calculations in addition to ICV (described below) which are commonly reported. Specifically, given their previously reported relationship with psychosocial factors in cancer populations, we chose to calculate the following: 1) cortisol slope [33], 2) evening cortisol [23], 3) morning cortisol [22], 4) the cortisol awakening response [24] and 5) total cortisol area under the curve (with respect to ground [30]). This approach to aggregating data has been shown to increase the reliability of cortisol data [21]. Each individual calculation is described in further detail below.

All analyses utilized Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21. To ensure the proper application of parametric statistics, all data were examined for outliers and investigated for characteristics of normality. If deemed nonnormal, an appropriate transformation was applied.

Raw cortisol data

Before the following analyses were conducted, cortisol values were examined for outliers and were included in analyses if values were within 4 standard deviations of the mean. In each of the calculations described below, each calculation was computed separately for each of the two days of salivary cortisol collection and each individual's mean was saved.

Cortisol slope

Slopes were calculated by regressing the measured salivary cortisol levels on time of collection, a method that is related to important clinical outcomes in women with cancer [33]. To isolate the diurnal rhythm within the day, the awakening plus 30 min time point was excluded from this analysis. Participants were asked to record their exact time of collection. To accurately calculate the cortisol slope for each individual, the measured cortisol values were regressed on the recorded times of collection. If participants did not record the exact time of collection, the mean time of collection (for that time point) from the entire sample was used. The regression weights were then saved for subsequent analyses.

Overall Cortisol Output

Area Under the Curve with respect to ground (AUCg) represents the total hormonal output throughout the day and was computed by applying a widely applied, published formula [30]. For this calculation, all 5 time points of salivary cortisol collection were included in the calculation.

Awakening cortisol

Out of the five time points collected, the collection time point upon awakening was retained separately for subsequent analyses. This was based on prior published research showing alterations in morning cortisol in major depression [20] and, in women with breast cancer, with symptoms of PTSD [22].

Evening cortisol

Evening cortisol was also retained as a separate variable to compare with baseline psychological measures, based on prior published research demonstrating that cortisol later in the day was lowered following a stress management intervention [4,28]. Further, in ovarian cancer, evening cortisol is related to vegetative depressive symptoms [23].

Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR)

A widely used calculation was applied to operationalize the cortisol awakening response, which used the awakening value of cortisol and the value collected 30 min after awakening: total area under the curve (AUCgCAR [30]). These calculations were included as the CAR is thought to represent its own regulatory process of the HPA-axis [15], separate from the summations of cortisol output throughout the day described above.

Intraindividual cortisol variability

This cortisol estimate, in concert with previous research in female cancer populations examining ICV [31], was the degree to which cortisol varied from the expected linear slope throughout the day, thus, the saliva collection time point at 30 min after awakening was excluded from further analysis.1 ICV estimations are described in detail elsewhere [31]. In brief, multilevel modeling was applied to estimate individual linear cortisol trends,2 the residuals were saved, and the standard deviation of these residuals was saved as its own variable [19]. Each individual's mean ICV was saved for the two days of salivary cortisol collection and averaged for each individual. Once deemed normal, the aforementioned cortisol calculations were compared with one another applying Pearson bivariate correlations, with no a priori hypotheses put forth regarding these comparisons. The significance level was set at α = .05.

Modeling change of cortisol over the course of the intervention

In addition to the multilevel models applied to create the ICV estimate for each individual, multilevel models [34] were also applied to assess a group by time interaction from baseline, to post-intervention, to 1 month following the intervention/comparison group. Only linear time trends were tested in concert with the k-2 rule of polynomials [34], given that 3 time points were measured. These models selected maximum likelihood estimation and were chosen given their flexibility with unequally spaced time points, handling of missing data and allowance for random intercepts (e.g., varying initial cortisol values; [18]). To remain parsimonious in the models tested, theoretically based covariates were tested in the primary aims’ model (e.g., modeling a potential group by time interaction for ICV) and included in the final model if they improved model fit (significantly lowered Akaike's Information Criteria based on a chi-square test comparison to the previous model) or significantly contributed the change of ICV over time. The following covariates were tested applying this strategy: age, baseline sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; [10]), health status (self-reported questionnaire), prior history of depression, or oral contraceptive use.

Results

Participant characteristics

Out of the 159 women enrolled, 91 provided a full day of cortisol samples and were included in subsequent analyses (full details of participant flow in Fig. 1). This included a total of 2279 total cortisol samples provided across the ten possible time points. Participants were primarily Caucasian (85.6%), non-Hispanic (96.6%) with a mean age of 44.2 (SD = 10.27). There were no statistically significant differences in any of the demographic variables examined between those who provided cortisol and those who did not. Similarly, there were not statistically different differences in history of depression or history of mental health treatment. Out of the 91 women retained in the current analyses, 44 were randomized to the CBSM intervention and 47 to the comparison group. There were no significant differences between those randomized to the CBSM or comparison groups and those whom provided sufficient cortisol samples to calculate an estimate of ICV (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic information between CBSM intervention and wait-list comparison groups.

| Variable | CBSM (n = 47) |

Comparison group (n = 44) |

Test statistic |

Effect size |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | n | M | (SD) | n | t-value | X 2 | p-value | d | Cramer's V | |

| Age | 43.63 | (10.47) | 44.73 | (10.15) | .51 | .61 | .11 | ||||

| BMI | 26.57 | (5.54) | 27.95 | (6.79) | 1.05 | .30 | .22 | ||||

| Education (years) | 17.55 | (2.07) | 16.91 | (2.34) | –1.35 | .18 | .29 | ||||

| Race | 4.17 | .38 | .22 | ||||||||

| Caucasian | 39 | 38 | |||||||||

| African-American | 0 | 3 | |||||||||

| Asian | 2 | 2 | |||||||||

| Other | 2 | 3 | |||||||||

| Ethnicitya | 3.18 | .12 | .19 | ||||||||

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 41 | 44 | |||||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 | 0 | |||||||||

| Perceived stress scale | 19.70 | (5.67) | 16.57 | (5.67) | .01 | .55 | |||||

| Center for epidemiological studies | 15.23 | (9.41) | 12.70 | (7.51) | .16 | .30 | |||||

| Breast cancer worry scale | 6.07 | (1.90) | 5.70 | (1.69) | .33 | .21 | |||||

Some participants (n = 3) chose not to answer this question.

Covariates

All covariates were centered prior to investigating whether they were significantly related to the linear time trend across the three study time points, or significantly improved model fit. Health status and sleep quality both significantly improved model fit of ICV (p = .02) and were retained in subsequent models. Participants included in the final analyses reported their average health as a 2.33 (SD = .76) on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 corresponding to “excellent” health and 5 corresponding to “poor” health. Regarding sleep quality, participants reported an average PSQI score of 6.34 (SD = 2.84), ranging from 2 to 15 in which higher scores indicate poor sleep quality and scores greater than 5 suggest sleep disturbance [10].

Correlations among cortisol calculations

A number of the cortisol calculations were highly correlated. These data are summarized in Table 2. In brief, the ICV estimate was significantly correlated with awakening cortisol (r = –.30; p = .004), such that a higher morning cortisol value was related to a lower ICV (e.g., less erratic). The relationship among a more pronounced cortisol awakening response and lower ICV approached significance (r = –.30; p = .06). Overall cortisol output was significantly correlated with awakening cortisol (r = .53; p = 8.32 E-8) evening cortisol (r = .60; p = .179 E-9) and CAR ((r = .62; p = .149 E-10). Further, slope was significantly correlated with evening cortisol (r = .81, p < 1.01E-20) and awakening cortisol was highly correlated with CAR (r = .81; p < .101 E-20). Finally, the relationship among CAR and evening cortisol reached statistical significance (r = .22; p = .045).

Table 2.

Correlations among cortisol calculations.*

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Slope | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2. Overall cortisol output (AUCg) | .20 | - | - | - | - |

| 3. Awakening cortisol | –.19 | .53** | - | - | - |

| 4. Evening cortisol | .81** | .60** | .16 | - | - |

| 5. Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR) | .029 | .62** | .81** | .22* | - |

| 6. Intraindividual Cortisol Variability (ICV) | .072 | .047 | –.30* | –.015 | –.20 |

p < .05.

p < .001.

Cortisol slope

Cortisol slope was calculated by regressing the individual time structure on natural log of cortisol values; however, these data remained non-normal and therefore a natural log transformation was also applied to these final summaries of linear cortisol slope for each participant. Out of all the models tested, cortisol slope demonstrated convergence problems with the variance components autocorrelation structure, thus after testing a number of covariance structures, a scaled identity represented the best fit to the data. In this model, the time by group interaction approached significance (β estimate = – .10; p = .073), suggesting that CBSM participants demonstrated a steeper linear slope (represented by a more negative β weight) compared to the comparison group.

Overall Cortisol Output

A natural log transformation was applied to AUCg summary scores, resulting in adequate characteristics of normality. In this model, the CBSM by time interaction approached significant (β estimate = −.062; p = .066), suggesting that CBSM participants demonstrated a lower overall cortisol output compared to the comparison group following the intervention and during the follow-up period.

Awakening cortisol

Awakening cortisol was normalized by applying a natural log transformation. A significant group by time interaction was not observed (β estimate = .067; p = .16).

Evening cortisol

Evening cortisol was also normalized by applying a natural log transformation. A significant group by time interaction did not emerge (β estimate = – .10; p = .19).

Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR)

The CAR demonstrated adequate characteristics of normality after a natural log transformation was applied. A significant group by time interaction was not observed (β estimate = .032; p = .37).

Intraindividual cortisol variability

The ICV estimate was skewed and kurtotic, thus a natural log transformation was used as the final dependent variable. After controlling for covariates that improved overall model fit (sleep quality and health status), a significant time by group interaction emerged (β estimate = – .070; p = .044), such that CBSM participants demonstrated a lower ICV following the intervention and in the follow-up period compared to the comparison group. All cortisol outcomes are reported in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics across time points of measurement for cognitive behavioral stress management and comparison groups.

| T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisol outcome | Mean (95% CI) | Median | IQR | Mean (95% CI) | Median | IQR | Mean (95% CI) | Median | IQR | |

| Slope | CBSM | –.121 (–.147, –.0946) | –.112 | .08 | –.164 (–.445, .1118) | –.217 | 1.07 | –.283 (–.543, –.0219) | –.307 | 1.04 |

| Comparison | –.115 (.134, –.0956) | –.124 | .10 | –.0179 (–.311, .2750) | –.0017 | 1.31 | .0964 (–.219, .412) | .1101 | 1.38 | |

| Overall cortisol output (AUCg) | CBSM | 4.759 (4.628, 4.889) | 4.653 | .57 | 4.803 (4.630, 4.976) | 4.716 | .62 | 4.705 (4.574, 4.836) | 4.681 | .57 |

| Comparison | 4.743 (4.595, 4.891) | 4.734 | .52 | 4.743 (4.594, 4.891) | 4.685 | .84 | 4.812 (4.643, 4.981) | 4.804 | .86 | |

| Awakening cortisol level | CBSM | 2.604 (2.439, 2.770) | 2.611 | .81 | 2.659 (2.513, 2.804) | 2.785 | .59 | 2.779 (2.615, 2.943) | 2.824 | .61 |

| Comparison | 2.708 (2.563, 2853) | 2.755 | .78 | 2.668 (2.455, 2.881) | 2.799 | .79 | 2.612 (2.412, 2.813) | 2.662 | .82 | |

| Evening cortisol level | CBSM | .812 (.343, 1.282) | .779 | 1.22 | .932 | .817 | 1.20 | .883 (.591, 1.175) | .867 | .97 |

| Comparison | .868 (.555, 1.180) | .728 | 1.39 | 1.058 (.699, 1.448) | .788 | 1.93 | 1.291 (.924, 1.659) | 1.368 | 1.87 | |

| Cortisol awakening response (CAR) | CBSM | 2.214 (2.081, 2.346) | 2.280 | .51 | 2.241 (2.124, 2.357) | 2.33 | .44 | 2.256 (2.121, 2.392) | 2.23 | .51 |

| Comparison | 2.22 (2.094, 2.353) | 2.262 | .59 | 2.165 (1.99, 2.336) | 2.286 | .65 | 2.131 (1.952, 2.309) | 2.195 | .54 | |

| Intraindividual cortisol variability (ICV) | CBSM | –.724 (–.885, –.562) | –.764 | .66 | –.911 (–1.064, –.759) | –.864 | .68 | –.850 (–1.047, –.652) | –.836 | .74 |

| Comparison | –.867 (–.991, –.745) | –.818 | .53 | –.838 (–.987, –.688) | –.729 | .67 | –.778 (–.923, –.632) | –.842 | .68 | |

IQR = Interquartile Range.

Table 4.

Cognitive behavioral stress management and Cortisol outcomes.

| Cortisol outcomea | Coefficient | SE | t | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | ||||

| Intercept | –.12 | .076 | –1.64 | (–.27, .025) |

| Group*time | –.10 | .055 | –1.80 | (–.21, .0094) |

| Overall Cortisol Output (AUCg) | ||||

| Intercept | 4.67 | .072 | 64.76 | (4.52, 4.81) |

| Group*time | –.062 | .033 | –1.85 | (–.13, .0042) |

| Awakening Cortisol Level | ||||

| Intercept | 2.75 | .085 | 32.38 | (2.59, 2.92) |

| Group*time | .067 | .047 | 1.42 | (–.027, .16) |

| Evening Cortisol Level | ||||

| Intercept | .76 | .14 | 5.35 | (.48, 1.05) |

| Group*time | –.10 | –1.31 | –1.31 | (–.26, .053) |

| Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR) | ||||

| Intercept | 2.15 | .061 | 35.56 | (2.03, 2.27) |

| Group*time | .032 | .036 | .90 | (–.039, .11) |

| Intraindividual Cortisol Variability (ICV) | ||||

| Intercept | –.85 | .062 | –13.66 | (–.98, –.73) |

| Group*time | –.070 | .034 | –2.03* | (–14, –.0018) |

ICV = Intraindividual cortisol variability.

All plots represent estimated marginal means from multilevel models.

P values are presented when models were significant or approached significance.

p < .05.

All cortisol outcomeswere log transformed and allmodels controlled for self-reported health and sleep quality (both grandmean centered), as both significantly improvedmodel fit for the primary cortisol outcome (ICV) of interest.

Discussion

The present study examined the hypothesis that stressed healthy women at risk for breast cancer who participated in a CBSM intervention would demonstrate a more regular (or less erratic) cortisol output throughout the day compared to a wait-list control group. Prior work has observed that cortisol rhythm throughout the day (linear slope) is related to important clinical outcomes in women with breast cancer such as fatigue [9] and mortality [33]. Consistent with hypotheses, CBSM participants had a significantly lower ICV following the intervention and during the one-month follow-up. While participants randomized to CBSM intervention trended towards a steeper cortisol slope and less overall cortisol output (AUCg; p = .073 and p = .066, respectively) compared to the comparison group, this relationship did not reach statistical significance. In contrast, the other three estimates of cortisol output did not demonstrate a CBSM group by time interaction.

A unique contribution of this study was the examination of how within-person fluctuations in cortisol may change over time following participation a stress management intervention. Prior reports have focused on cross-sectional study designs in participants with psychiatric conditions [17,27], suggesting that great variability in cortisol output is related to the presence of the conditions studied (major depression and remitted bipolar disorder, respectively) compared to controls. The current sample consisted of a group of healthy women who reported high levels of distress at study entry; however, these levels were not to the degree that they were indicative of psychopathology. This makes a direct comparison difficult with prior work on cortisol variability. Nevertheless, if these clinical conditions are conceptualized as manifestations of exposure to long-term psychological distress, it is noteworthy that a physiological correlate of these conditions (e.g., ICV) may be reduced through participation in a CBSM intervention. Given that recent work in women undergoing surgery for endometrial cancer suggests that greater ICV may be related to increased depressive symptoms [31], it is also compelling that ICV may be attenuated by participation in CBSM intervention. Future research should examine ICV outcomes after CBSM among women facing cancer diagnoses, as well as women who may meet criteria for the aforementioned psychiatric conditions at the time of diagnosis or over the course of corresponding treatment.

The data presented herein are also noteworthy in that multiple cortisol calculations were compared concurrently. A number of published studies have observed no demonstrable changes in cortisol rhythm/output following participation in a stress management intervention. While no published work to our knowledge has examined intraindividual cortisol variability in the context of a stress management intervention, it is interesting that this calculation showed a significant difference between groups, whereas as other calculations did not demonstrate a significant difference between groups.

These results should be interpreted with caution, as this study has a number of limitations. First, the study aims of this secondary data analyses are focused on ICV exclusively, and it remains unclear how the ICV estimate in this sample is related to other cortisol calculations. As the majority of work examining similar stress management interventions (e.g., CBSM) reports an intervention effect on lowering overall cortisol levels [2,12], it may be hypothesized that participants in the CBSM study would have lower cortisol levels than participants in the comparison group. Second, and also beyond the scope of this paper, ICV was not compared to measures of psychological distress. In prior work, higher levels of depressive symptoms were related to greater ICV in women undergoing surgery for cancer [31]. It will be worthwhile in future investigations to examine whether changes in distress are also related to reductions in ICV between groups as the intervention described herein mitigated depressive symptoms and perceived stress [25]. Third, only 4 time points of salivary collection were used to generate the ICV estimate and a larger, more robust sampling protocol may yield different results. Prior studies have applied hourly serum collections [40] to fully capture the circadian, sinusoidal rhythm observed in cortisol output. Thus, the current results may not be directly comparable to these more comprehensive sampling procedures and the analytic methods applied to such data. Finally, a large portion of participants neglected to provide a complete set of 5 salivary cortisol samples (68 out of 159 randomized; or 42.8%). The present results may represent a population that was self-selected based on their ability to completely follow all study procedures (e.g., collecting salivary cortisol). Similarly, this may explain the low dropout rate across the time points analyzed in the current study.

Conclusions

In summary, ICV may represent a novel index of cortisol dysregulation that is impacted by participation in a stress management intervention. Future research should examine these relationships in larger samples, across different clinical conditions and examine the relationship between ICV and potential immune and general health outcomes.

Footnotes

Funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute (K07 CA107085-01; McGregor).

Additional support by T32AG044296 (Sannes).

All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Cancer Institute or any of the funding agencies listed above.

Clinical Trials identifier: NCT01048528

This eliminated the well documented cortisol awakening response [42] which was not an outcome of interest for this calculation.

b1: Yij = b0 + u0i + (b1 + u1i)Xij + eij. Each individual's (i) average linear trend was modeled on cortisol's (Yij) linear relationship to recorded time of collection (Xij) with a linear mixed model specifying random intercepts and slopes (varying by individual an amount u0i from the intercept b0 and an amount u1i from the slope).

Declaration of interest

The authors claim no conflict of interest in presentation of this work.

References

- 1.Adam EK, Kumari M. Assessing salivary cortisol in large-scale, epidemiological research. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(10):1423–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antoni MH, Cruess S, Cruess DG, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management reduces distress and 24-hour urinary free cortisol output among symptomatic HIV-infected gay men. Ann. Behav. Med. 2000;22(1):29–37. doi: 10.1007/BF02895165. Winter. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antoni MH, Cruess DG, Klimas N, Carrico AW, Maher K, Cruess S, et al. Increases in a marker of immune system reconstitution are predated by decreases in 24-h urinary cortisol output and depressed mood during a 10-week stress management intervention in symptomatic HIV-infected men. J. Psychosom. Res. 2005;58(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antoni MH, Lechner S, Diaz A, Vargas S, Holley H, Phillips K, et al. Cognitive behavioral stress management effects on psychosocial and physiological adaptation in women undergoing treatment for breast cancer. Brain Behav. Immun. 2009;23(5):580–591. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Kilbourn KM, Boyers AE, Culver JL, Alferi SM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2001;20(1):20–32. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armaiz-Pena GN, Lutgendorf SK, Cole SW, Sood AK. Neuroendocrine modulation of cancer progression. Brain Behav. Immun. 2009;23(1):10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belanoff JK, Kalehzan M, Sund B, Fleming Ficek SK, Schatzberg AF. Cortisol activity and cognitive changes in psychotic major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158(10):1612–1616. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhattacharyya MR, Molloy GJ, Steptoe A. Depression is associated with flatter cortisol rhythms in patients with coronary artery disease. J. Psychosom. Res. 2008;65(2):107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Aziz N. Altered cortisol response to psychologic stress in breast cancer survivors with persistent fatigue. Psychosom. Med. 2005;67(2):277–280. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000155666.55034.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson LE, Doll R, Stephen J, Faris P, Tamagawa R, Drysdale E, et al. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based cancer recovery versus supportive expressive group therapy for distressed survivors of breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31(25):3119–3126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.5210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cruess DG, Antoni MH, McGregor BA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management reduces serum cortisol by enhancing benefit finding among women being treated for early stage breast cancer. Psychosom. Med. 2000 May-Jun;62(3):304–308. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costanzo ES, Sood AK, Lutgendorf SK. Biobehavioral influences on cancer progression. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2011;31(1):109–132. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fekedulegn DB, Andrew ME, Burchfiel CM, Violanti JM, Hartley TA, Charles LE, et al. Area under the curve and other summary indicators of repeated waking cortisol measurements. Psychosom. Med. 2007;69(7):651–659. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31814c405c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fries E, Dettenborn L, Kirschbaum C. The cortisol awakening response (CAR): facts and future directions. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2009;72(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140(6):883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Havermans R, Nicolson NA, Berkhof J, deVries MW. Patterns of salivary cortisol secretion and responses to daily events in patients with remitted bipolar disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;36(2):258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hruschka DJ, Kohrt BA, Worthman CM. Estimating between- and within-individual variation in cortisol levels using multilevel models. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30(7):698–714. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hultsch DF, MacDonald S. Intraindividual variability in performance as a theoretical window onto cognitive aging. New Front. Cogn. Aging. 2004:65–88. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knorr U, Vinberg M, Kessing LV, Wetterslev J. Salivary cortisol in depressed patients versus control persons: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(9):1275–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kraemer HC, Giese-Davis J, Yutsis M, O'Hara R, Neri E, Gallagher-Thompson D, et al. Design decisions to optimize reliability of daytime cortisol slopes in an older population. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 2006;14(4):325–333. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000201816.26786.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luecken LJ, Dausch B, Gulla V, Hong R, Compas BE. Alterations in morning cortisol associated with PTSD in women with breast cancer. J. Psychosom. Res. 2004;56(1):13–15. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00561-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lutgendorf SK, Weinrib AZ, Penedo F, Russell D, DeGeest K, Costanzo ES, et al. Interleukin-6, cortisol, and depressive symptoms in ovarian cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26(29):4820–4827. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matousek RH, Pruessner JC, Dobkin PL. Changes in the cortisol awakening response (CAR) following participation in mindfulness-based stress reduction in women who completed treatment for breast cancer. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2011;17(2):65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGregor BA, et al. Cognitive Behavioral Stress Management for Healthy Women at Risk for Breast Cancer: A Novel Application of a Proven Intervention. Ann. Behav. Med. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9726-z. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miovic M, Block S. Psychiatric disorders in advanced cancer. Cancer. 2007;110(8):1665–1676. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peeters F, Nicolson NA, Berkhof J. Levels and variability of daily life cortisol secretion in major depression. Psychiatry Res. 2004;126(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillips KM, Antoni MH, Lechner SC, Blomberg BB, Llabre MM, Avisar E, et al. Stress management intervention reduces serum cortisol and increases relaxation during treatment for nonmetastatic breast cancer. Psychosom. Med. 2008;70(9):1044–1049. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318186fb27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Posener JA, Charles D, Veldhuis JD, Province MA, Williams GH, Schatzberg AF. Process irregularity of cortisol and adrenocorticotropin secretion in men with major depressive disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29(9):1129–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pruessner J, Kirschbaum C, Meinlschmid G, Hellhammer D. Two formulas for computation of the area under the curve represent measures of total hormone concentration versus time-dependent change. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28(7):916–931. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sannes TS, Jensen SE, Dodd SM, Kneipp SM, Garey Smith S, Patidar SM, et al. Depressive symptoms and cortisol variability prior to surgery for suspected endometrial cancer. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(2):241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sephton SE, Lush ED, Dedert EA, Floyd AR, Gesler WN, Dhabhar FS, et al. Diurnal cortisol rhythm as a predictor of lung cancer survival. Brain Behav. Immun. 2013;30(S):S163–S170. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sephton SE, Sapolsky RM, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Diurnal cortisol rhythm as a predictor of breast cancer survival. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2000;92(12):994–1000. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.12.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singer JD, Willet JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. Oxford University Press, Oxford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turner-Cobb JM, Sephton SE, Koopman C, Blake-Mortimer J, Spiegel D. Social support and salivary cortisol in women with metastatic breast cancer. Psychosom. Med. 2000;62(3):337–345. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200005000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Volden PA, Conzen SD. The influence of glucocorticoid signaling on tumor progression. Brain Behav. Immun. 2013;30(Suppl):S26–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Webster Marketon JI, Glaser R. Stress hormones and immune function. [review] Cell. Immunol. 2008;252(1–2):16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinrib AZ, Sephton SE, Degeest K, Penedo F, Bender D, Zimmerman B, et al. Diurnal cortisol dysregulation, functional disability, and depression in women with ovarian cancer. [research support, N.I.H., extramural] Cancer. 2010;116(18):4410–4419. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wust S, Wolf J, Hellhammer DH, Federenko I, Schommer N, Kirschbaum C. The cortisol awakening response — normal values and confounds. Noise Health. 2000;2(7):79–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yehuda R, Teicher MH, Trestman RL, Levengood RA, Siever LJ. Cortisol regulation in posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression: a chronobiological analysis. Biol. Psychiatry. 1996;40(2):79–88. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00451-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Young EA, Abelson J, Lightman SL. Cortisol pulsatility and its role in stress regulation and health. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2004;25(2):69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kudielka BM, Wust S. Human models in acute and chronic stress: assessing determinants of individual hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis activity and reactivity. Stress. 2010;13(1):1–14. doi: 10.3109/10253890902874913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]