Abstract

Intracellular triacylglycerol (TAG) is a ubiquitous energy storage lipid also involved in lipid homeostasis and signaling. Comparatively, little is known about TAG’s role in other cellular functions. Here we show a pro-longevity function of TAG in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In yeast strains derived from natural and laboratory environments a correlation between high levels of TAG and longer chronological lifespan was observed. Increased TAG abundance through the deletion of TAG lipases prolonged chronological lifespan of laboratory strains, while diminishing TAG biosynthesis shortened lifespan without apparently affecting vegetative growth. TAG-mediated lifespan extension was independent of several other known stress response factors involved in chronological aging. Because both lifespan regulation and TAG metabolism are conserved, this cellular pro-longevity function of TAG may extend to other organisms.

Author Summary

Triacylglycerol (TAG) is a ubiquitous lipid species well-known for its roles in storing surplus energy, providing insulation, and maintaining cellular lipid homeostasis. Here we present evidence for a novel pro-longevity function of TAG in the budding yeast, a model organism for aging research. Yeast cells that are genetically engineered to store more TAG live significantly longer without suffering obvious growth defects, whereas those lean cells that are depleted of TAG die early. Yeast strains isolated from the wild in general contain more fat and also display longer lifespan. One of the approaches taken here to force the increase of intracellular TAG is to delete lipases responsible for lipid hydrolysis. Energy extraction from TAG thus is unlikely an underlying cause of the observed lifespan extension. Our results are reminiscent of certain animal studies linking higher body fat to longer lifespan. Potential mechanisms for the connection of TAG and yeast lifespan regulation are discussed.

Introduction

Lipid is essential for all life forms on earth. Polar lipids, most notably phospholipids, are the primary components of biological membranes, whereas neutral lipids such as triacylglycerols (TAG; or triglycerides, TG), are long believed to store excessive energy and to provide thermal and physical insulation for animals. By esterifying three molecules of fatty acids to the glycerol backbone, TAG packs the highest density of chemical energy among major biomolecules, consistent with a role in storing surplus energy. In addition, TAG metabolism is linked to the overall lipid homeostasis in cells and the organism [1]. This is commonly achieved via diacylglycerol, DAG, which is a shared precursor for TAG and phospholipids biosynthesis. Interestingly, in many organisms, TAG accumulation is not a response of surplus nutrients, but of different stresses. For example, starvation for nitrogen, phosphorus, or sulfur causes a model photosynthetic microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii to accumulate TAG [2, 3]. Even the oleaginous marine alga Nannochloropsis species increase the TAG content by 50% when starved of nitrogen, and to a lesser extent when stressed by high light and salinity [4]. In animals, mild (5%) calorie restriction administered to laboratory mice shifted the relative abundance of fat and muscle by increasing the fat mass by 68%, and reducing the lean mass by 12%, with total bodyweight remained unchanged [5]. In budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a minimal amount of TAG is synthesized by vegetatively growing cells. When glucose becomes limited and that cells enter the stationary phase, TAG synthesis rises sharply [6]. One apparent reason for these organisms to maintain a larger storage of TAG under stress is to cope with the uncertainties of the environments. By storing chemical energy and materials for membrane lipid biosynthesis, TAG helps the underlying cells quickly resume robust metabolism and growth when conditions improve. On the other hand, whether the existence of TAG in cells affords other benefits for survival through the environmental stress remains an unaddressed question.

TAG is composed of a glycerol backbone esterified to three fatty acids by acyl coenzyme A:diacylglycerol acyltransferases, DGATs, and phospholipid:diacylglycerol acyltransferases, PDATs. In budding yeast, Dga1p and Lro1p are the major DGAT and PDAT, respectively [7]. Of these two, Lro1p appears to be responsible for TAG synthesis in vegetatively growing cells, whereas Dga1p contributes more significantly to the post-diauxic shift accumulation of TAG [8–10]. In addition to TAG, fatty acids can be esterified to sterols to form steryl esters (SE), another class of storage neutral lipids [10]. The two major enzymes responsible for SE biosynthesis are Are1p and Are2p [10]. In contrast to the stark differentiation of TAG abundance in log and stationary phase cells, SEs are maintained at a constant level at different phases of the growth curve [11], suggesting a function unique to TAG in the stationary phase. Intriguingly, deleting the four major neutral lipid biosynthetic genes (DGA1, LRO1, ARE1, ARE2), while causing yeast cells to lose practically all storage neutral lipids, does not result in significant deleterious effects in vegetatively growing cells [10]. However, these lean cells are hypersensitive to exogenous fatty acids and die with a phenotype of membrane over-proliferation [12], indicating that maintaining the capacity of incorporating excessive free fatty acids in the form of TAG or SE affords an important means to prevent lipotoxicity of free fatty acids. Accumulation of TAG and SE in the ER membrane causes expansion of the membrane, which eventually buds out to form lipid droplets (LD), a dynamic phospholipid monolayered organelle that has gained increasing research interests [13, 14]. A variety of proteins have been found associated with LD, including multiple TAG and SE hydrolases and signaling proteins that together play important roles in lipid homeostasis [15]. The yeast TGL3 and TGL4 genes encode the two major TAG lipases in yeast; additional lipases Tgl5p, Ayr1p and Lpx1p appear to be less robust enzymatically [16]. Tgl4p, which is thought to be the functional orthologue of the mammalian ATGL [17, 18], has been shown to be regulated by Cdk1-mediated phosphorylation in G1-to-S transition of dividing cells [19]. Blocking this phosphorylation event delays bud emergence. Deleting either or both major TAG lipases causes accumulation of TAG in stationary phase cells without a clear growth defect [18]. Similar to TAG, SE can be broken down by functionally redundant lipases Tgl1p, Yeh1p, and Yeh2p [20, 21]. SE lipase triple knockout cells, aside from possessing a significantly larger pool of SE, are phenotypically indistinguishable from the wildtype counterpart [20]. Together, these studies demonstrated clearly that yeast cells have the capacity of metabolizing neutral storage lipids. However, these lipids are not essential for cellular viability.

Budding yeast has been a model for two modes of aging [22, 23], chronological lifespan (CLS) and replicative lifespan (RLS). CLS refers to the overall viability of stationary-phase cells over time. RLS examines the number of daughters that each mother cell can produce before ceasing division. These two modes simulate, respectively, the senescence of post-mitotic (e.g., muscles and neurons) and stem cells in metazoans. Chronological aging in yeast has been linked closely to the nutrient status. When glucose is depleted, yeast cells exit from the log phase to enter diauxic shift, then into the stationary phase, a mitotically inactive yet metabolically active state [24]. The population viability is maintained in cells that enter the quiescent state [25, 26]. However, over time, the number of viable quiescent cells diminishes as well, resulting in a progressive increase of population mortality, a condition similar to metazoans including humans [22]. While there are yeast-specific chronological senescence and longevity factors (e.g., acetic acid and glycerol, respectively) [27, 28], a number of pathways are conserved [22, 23]. Some of the most notable pro-aging pathways include the Target Of Rapamycin (TOR)/S6 kinase (Sch9p in yeast) [29] and the Ras/adenylate cyclase/PKA pathways [30]. Intriguingly, these pathways control both CLS and RLS [23]. These two pathways are activated in response to the intake of selective nutrients, and are suppressed by caloric restriction, consistent with many reports that different organisms extend their lifespan when subjected to calorie restriction [31, 32]. Other pro-aging factors include oxidative stresses [33], mitochondrial dysfunction [34, 35], defective autophagy [36], DNA damages and replication stresses [37], and metabolic alterations [38]. Yeast genome-wide studies have identified a variety of gene mutations that extend chronological lifespan [39–42]. Many of these genes are involved in the metabolism of amino acids, nucleotides, or alternative carbon source, further underscoring the important roles played by metabolites in the control of lifespan. However, despite these relatively unbiased screens, very little is known regarding the role of lipids in the control of CLS. Here we present evidence for a novel energy usage-independent, anti-senescence function of TAG in yeast.

Results

TAG extends chronological lifespan

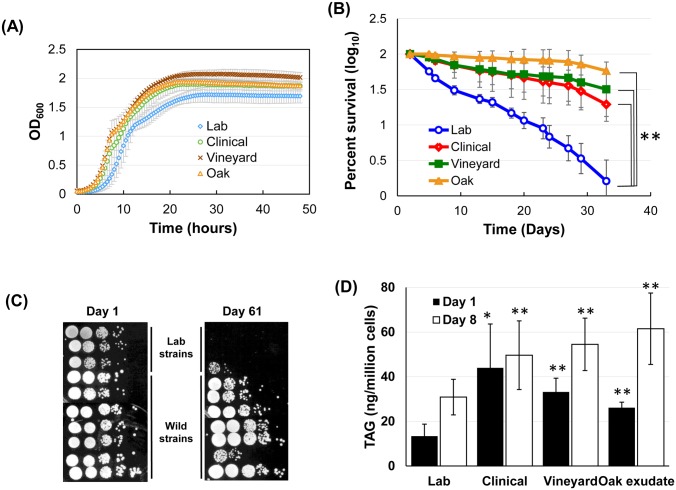

Budding yeast is an excellent model for elucidating gene functions, biochemical pathways, stress responses, and aging. Natural variations among yeast strains, including traits altered during laboratory domestication may help uncover the relationships between genotype and phenotype [43, 44]. We speculated that phenotypic differences between laboratory and wild isolates could reveal important biological information, including the relationship between lipid and aging. To this end, we first examined the growth curves, under standard laboratory growth conditions, of eight wild strains isolated from diverse natural environments and three laboratory strains. These wild strains were ho- (i.e., unable to switch mating type) haploid segregants of isolates from vineyards, oak exudates, and clinical samples. The three laboratory strains were yMK839, a derivative of EG123 [45], W303, and BY4742. Fig 1A shows that, in general, wild strains had a shorter lag phase and faster growth rate in log phase than laboratory strains (doubling time in YPD: lab, 94 ± 2 min; wild, 80 ± 3 min). In addition, the cell density at saturation, i.e., stationary phase, was also higher for the wild strains. The ability to accumulate higher cell density in spent medium indicated that these wild strains may have adapted more effectively to nutrient limitations in a harsh environment, and, if true, further suggested that such cells might survive better through stationary phase than their domesticated counterparts. To test this hypothesis, we measured the percent of cells able to re-enter vegetative growth from revival of the saturated cultures over a period of one month, using the quantitative “outgrowth” approach developed by Kaeberlein and colleagues [46]. The survival plot in Fig 1B demonstrates higher viability of wild strains. In a separate “spot assay”, cells cultivated for 61 days were serially diluted and spotted to a fresh solid medium. Two of the three laboratory strains fell below the detection limit of this assay, whereas the majority of the wild strains were capable of forming new colonies, indicating higher survival rates (Fig 1C).

Fig 1. Wild yeast strains from different origins accumulate higher levels of triacylglycerol (TAG) and exhibit longer chronological lifespan.

(A) Growth curves of wild strains isolated from oak exudates, vineyards, and clinical samples vs. three laboratory strains. Cells were grown in YPD at 30° in a 96-well plate. Each curve represents the average of growth of 2 to 4 strains in the category. Shown are representative results from two biological replicates. (B) Chronological lifespan in SC medium was measured by the “outgrowth” approach. (C) Chronological lifespan examined by spot assays. Viability of cultures was assayed every 3 to 5 days for two months. Only day 1 (all strains showed close to 100% viability) and day 61 images are shown. Cultures were 10-fold serially diluted in water before inoculation. (D) Quantification of triacylglycerol of cells harvested from day 1 and day 8 post-saturation YPD cultures.

Fig 1A–1C suggest that the laboratory domestication of S. cerevisiae might have artificially selected for certain physiology features leading to distinct phenotypes in the stationary phase [47]. Microscopic inspection of 5-day old stationary phase cells revealed more abundant cytoplasmic granules stainable by the neutral lipid dye Nile red in wild strains (S1 Fig). These Nile red stained lipid droplets are organelles that store neutral lipids, i.e., triacylglycerol and steryl esters [14]. Whereas the SE level stays constant through the growth curve [11], TAG abundance rises sharply when cells enter the stationary phase [6]. TAG thus seemed to be a plausible causal link to the observed difference in survival following saturation. To test this hypothesis, we first quantified cellular TAG abundance of day-1 and day-8 post-saturation cultures. Consistent with the microscopic observations, the wild strains contained higher levels of TAG at both time points (Fig 1D), providing a positive correlation between TAG abundance and survival.

The differential age-dependent survival shown above is equivalent to yeast chronological lifespan [48, 49], suggesting that TAG may have a role in maintaining or even extending chronological lifespan. To understand the causal relationship between TAG metabolism and chronological lifespan, we turned to a laboratory strain (yMK839) for genetic manipulation and phenotypic assessment.

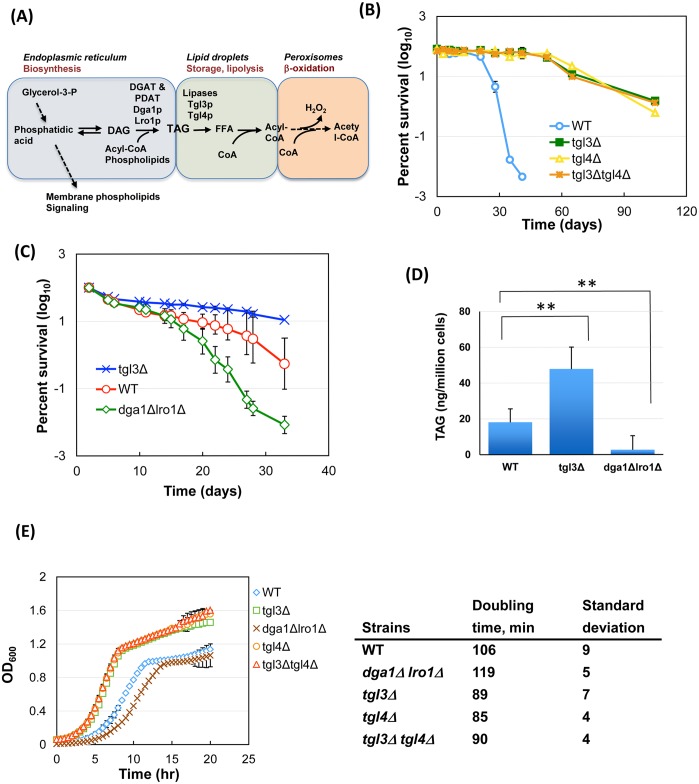

In yeast, Dga1p and Lro1p are the major TAG biosynthetic enzymes (Fig 2A). The aliphatic chain of each constituent fatty acid contains chemical energy that can be converted to metabolically useful energy by a series of -oxidation reactions taking place in peroxisomes, following lipolysis by lipases Tgl3p and Tgl4p [18, 50, 51]. To test whether the increased TAG storage prolongs chronological lifespan, we deleted TGL3 and TGL4, which caused TAG accumulation while blocking energy extraction from this lipid species. Consistent with published results [18, 51], the TAG level was elevated in tgl3Δ, tgl4Δ, and tgl3Δ tgl4Δ strains at stationary phase (S2 Fig). Importantly, all three TAG-rich strains showed extension of chronological lifespan (Fig 2B, and S5 Fig rows 2 to 4). These results indicate that the storage of TAG, but not its hydrolysis as a prerequisite for energy conversion or other cellular uses, is associated with improved viability in stationary phase. Intriguingly, deleting the TAG lipase did not cause discernible defects in doubling time (Fig 2E), mating efficiency of haploid cells, or sporulation of homozygous tgl3Δ/tgl3Δ cells (S3 Fig). Because deleting either or both TAG lipase genes resulted in similar phenotypes with respect to TAG accumulation and lifespan extension (Fig 2B), the tgl3Δ strain is representatively shown in further experiments below.

Fig 2. Elevated intracellular TAG level promotes longevity during chronological aging, whereas TAG depletion shortens lifespan.

(A) Abbreviated view of TAG metabolism in yeast. (B) A laboratory strain yMK839 and its single and double lipase knockout derivatives were grown deeply into stationary phase in SC medium. At different time points, cells were spread to fresh YPD plates to quantify the colony forming units, expressed as percent survival. The plot was from two biological replicates of each strain. (C) Deleting DGA1 and LRO1 causes early death in stationary phase. Shown are averages of five biological repeats by the outgrowth approach. ** p < 0.01. Note the difference in time scale between panel B and panel C. Also, the two different assays for chronological lifespan quantification, i.e., colony forming units and outgrowth method, might give rise to differences in the absolute numbers of percent survival. The former did not differentiate colony size variations, whereas the latter outgrowth assay, which relied on the population growth rate, would be impacted by differences in doubling time and in the time when a cell exited the lag phase. (D) Quantification of intracellular TAG from day-8 post-saturation cultures in SC medium. (E) Growth comparison of yMK839 and its TAG-rich and -depleted derivatives. Growth curves were obtained as in Fig 1A.

Blocking TAG hydrolysis also diminishes downstream reactions, including peroxisomal -oxidation that produces H2O2 that may cause oxidative stresses and cell death [52]. If a reduction of lipolysis-associated H2O2 production was solely responsible for the observed viability retention, deleting the two major TAG biosynthetic acyltransferases, Dga1p and Lro1p, would prevent TAG synthesis and the subsequent -oxidation (Fig 2A), and a similar beneficial effect on longevity would result as well. However, phenotypic analysis of the dga1Δ lro1Δ strain revealed the opposite. Deleting the two TAG biosynthetic acyltransferases caused a reduction of chronological lifespan (Fig 2C, and S5 Fig, row 6) and nearly eliminated cellular TAG (Fig 2D). The log phase growth rate also was reduced by the double deletion by approximately 12% (Fig 2E), which likely resulted from a defect in maintaining the cell’s replicative potential (see Fig 6 and below). This shortened chronological lifespan could not be rescued by deleting TGL3 (S5 Fig, row 5), underscoring the necessity of keeping the physical presence of TAG to maintain cellular viability during stationary phase.

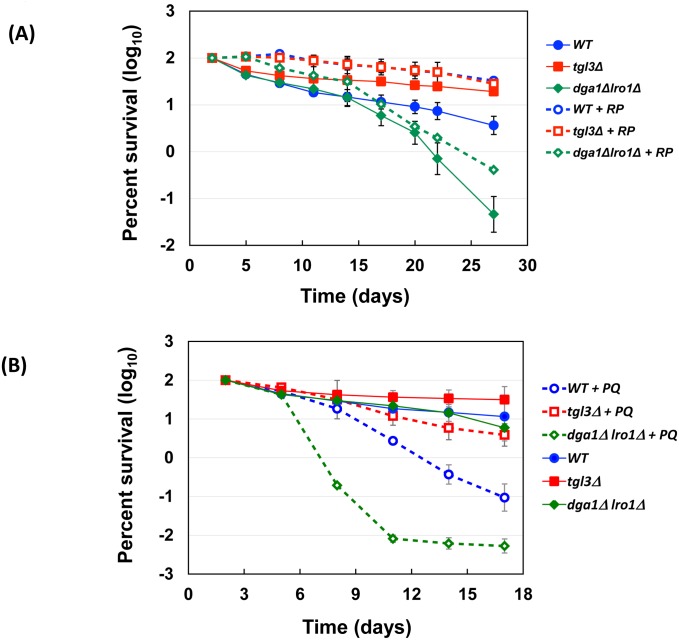

Fig 6. Rapamycin and paraquat respectively extends and shortens lifespan of the three core strains.

10 nM of Rapamycin (RP, panel A) and 10 μM of paraquat (PQ, panel B) were included in SC medium to assess the effects on the lifespan. Other parameters were identical to experiments shown in Fig 2C.

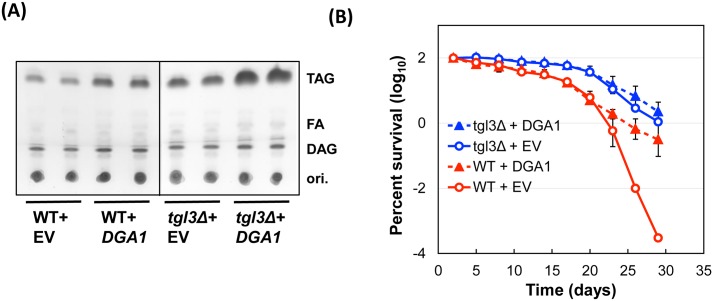

To further confirm the pro-longevity role of TAG, we overexpressed a TAG biosynthetic enzyme Dga1p [9] by introducing a multi-copy plasmid bearing DGA1 under the control of the native DGA1 promoter or a constitutive ADH1 promoter to TGL3+ and tgl3Δ strains. Cells from day-8 post-saturation cultures were processed for lipid extraction and TAG quantification. Data in Fig 3A confirmed the increased TAG content by Dga1p overproduction. The wildtype cells with a higher level of TAG exhibited longer lifespan (Fig 3B), strongly suggesting that TAG plays a causal role in preserving cellular viability during chronological senescence. Intriguingly, while Dga1p overexpression also raised the TAG content in tgl3Δ cells, the lifespan extension was relatively minor in this already long-living background. This observation indicates a limit of lifespan extension by TAG. Taking together the data in Figs 1 to 3, we conclude that intracellular triacylglycerol is essential for the maintenance of chronological lifespan, and that forcing the accumulation of TAG by either blocking its hydrolysis or increasing its biosynthesis, can extend lifespan.

Fig 3. Overproducing Dga1p increases TAG abundance and extends chronological lifespan.

(A) Thin-layer chromatography of neutral lipids from eight-day old stationary phase cultures bearing either the empty vector (EV) or one that expresses Dga1p. DAG, diacylglycerol; FA, free fatty acids; ori., origins for chromatography. The two EV lanes in panel A are biological duplicates; each of the two DGA1 lanes represents the two different constructs with DGA1 or ADH1 promoter driving the recombinant gene expression. (B) Survival curves. These are averages of four DGA1 overexpression isolates (two of each plasmid transformants), and two vector control duplicates. To accommodate the use of episomal plamids, yeast cells were grown in SC-uracil medium, which, compared with the use of synthetic complete medium seen in Figs 1 and 2, likely caused slightly faster viability loss of all strains analyzed.

TAG promotes longevity independently of other lifespan control pathways

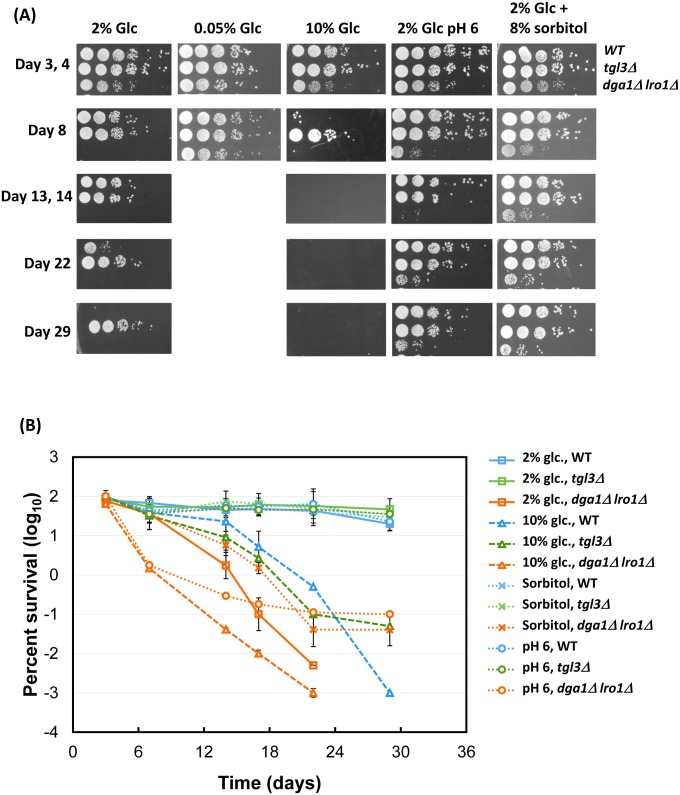

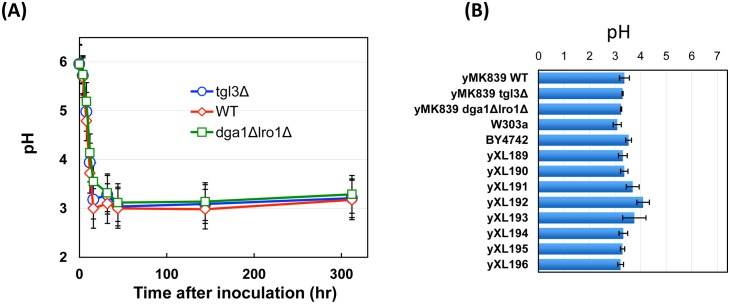

The yeast chronological lifespan is regulated by common as well as yeast-specific factors. Rapamycin and paraquat extends and shortens lifespan, respectively [40, 53]. Caloric restriction, e.g., reducing the initial glucose concentration from 2% to 0.5% or lower in the medium, promotes longevity, whereas excessive glucose (e.g., 10%) shortens it. More specific to yeast is medium acidification from fermentation that causes senescence, an aging mechanism that can be antagonized by using a buffered, neutral pH medium [27, 54, 55]. We examined the relationship between TAG and these lifespan regulators, and found that the lifespan-extending regimes of caloric restriction (0.05% glucose), medium neutralization (pH6 with citrate phosphate), and high osmolarity (8% sorbitol) all delayed senescence for both the yMK839 wildtype and its TAG-depleted derivative (Fig 4A and 4B), with the latter still exhibiting shorter lifespan. The exceptionally long lifespan of tgl3Δ cells prohibited us from quantitatively assessing the effect of these lifespan extending treatments. 10% glucose caused all three strains to die early, yet the lipase-null cells remained to be the longest-living strain, suggesting strongly that CLS regulation by the abundance of TAG operates in a novel pathway. The observation that medium neutralization effectively extended the lifespan of dga1Δ lro1Δ and wildtype cells (Fig 4A fourth column from left) could be interpreted as that differences in medium acidification underlay the observed differential lifespan. However, direct measurement of the medium pH of the three normal, lean, and fat strains for more than 10 days (Fig 5A), or of 4-day old cultures of the three lab strains and 8 wild strains (Fig 5B) revealed statistically indistinguishable degrees of medium acidification. These data therefore ruled out that changes in the TAG level would alter the acidity of the medium and, consequently, the lifespan of cells. Together, Figs 4 and 5 demonstrate that the chronological lifespan can be controlled by the abundance of intracellular TAG in a mechanism that is independent of pathways involving glucose, medium pH and osmolarity.

Fig 4. TAG-medicated lifespan control is independent of several yeast-specific and common lifespan regulatory regimes.

(A) Semi-quantitative comparison of lifespan of the three “core” strains used in this study: wildtype (WT), TAG lipase knockout (tgl3Δ), and TAG synthesis deficient mutant (dga1Δ lro1Δ) under different growth conditions. Glc, glucose; the medium neutralization experiment (fourth column from left) was done with SC medium supplemented with 64.2 mM Na2HPO4 and citric acid to stabilize the pH at 6.0. Shown are representative results of 2 or 3 biological repeats. (B) Quantitation of the spot assay results. All data were from three biological duplicates.

Fig 5. Culture medium pH changes are comparable among strains with different chronological lifespan.

The pH changes of YPD cultures were monitored for 312 hours after inoculating overnight cultures to fresh medium (Panel A). In a second set of experiments (Panel B) the medium pH was measured from 4-day old YPD cultures of the indicated lab and wild strains. n ≥ 3.

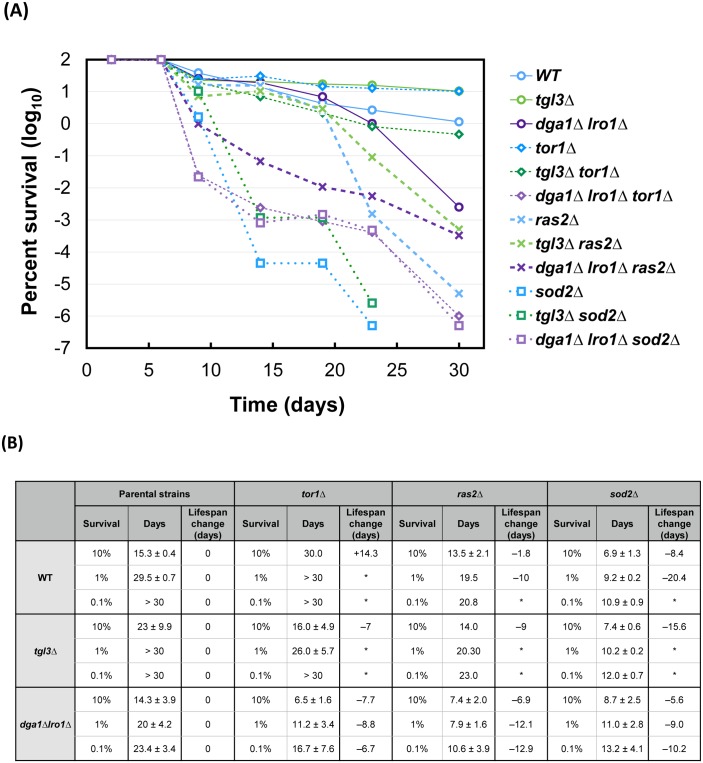

Rapamycin and paraquat are two potent extragenic lifespan modulators for many species [31, 40]. When treated with these two compounds, all three core strains responded similarly. That is, rapamycin extended, whereas paraquat shortened the lifespan of all three (Fig 6). When several highly conserved lifespan control genes TOR1, RAS2, and SOD2 were deleted from the three core strains, we observed differential responses (Fig 7A). From the time for each strain to drop to 10%, 1%, and 0.1% viability (Fig 7B), it is clear that deleting TOR1 made the wildtype strain live longer, in agreement with previous findings [28]. Intriguingly, despite that rapamycin (10 nM) treatment prolonged cellular survival (Fig 6A), deleting the entire Target of Rapamycin TOR1 gene actually shortened the lifespan of both the fat, tgl3Δ cells and the lean, dga1Δ lro1Δ cells (Fig 7). Because these lipase- and DGAT-deficient strains were unable to extract energy from TAG metabolism, we suspect that tor1Δ cells survived at least partly on the energy stored in TAG. Lacking either TGL3 or DGA1 and LRO1 resulted in the loss of viability during chronological aging. In contrast to the differential effects TOR1 deletion, knocking out RAS2 or SOD2 shortened lifespan of all three parental strains (crosses and open squares, Fig 7A). RAS2 in the RAS/cAMP/PKA pathway is involved in stress response and lifespan control [56]. Deleting RAS2 has been shown to preserve chronological lifespan [28]. However, a genome-wide screen showed reduced survival of chronologically aging ras2Δ cells [57]. In our hands, all ras2Δ strains died earlier than their corresponding parental strains regardless of the TAG content (Fig 7A, cross markers, and Fig 7B summary), suggesting that Ras2p controls the lifespan in a TAG-independent manner. Similarly, deleting SOD2, which encodes a mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase that is a key to the defense against reactive oxygen species originated from mitochondria, and to the preservation of full lifespan potential [58], significantly reduced the life expectancy of all three strains. These observations suggest that Sod2p remained to be a critical vitality enzyme in the long-living tgl3Δ cells, and that TAG likely functions independently of Sod2p to protect aged cells.

Fig 7. TAG controls chronological lifespan independently of conserved pathways.

TOR1, RAS2, and SOD2 were deleted from the three core strains with a normal, higher, and lower TAG content. The resultant strains were grown for outgrowth assays to compare their CLS with the corresponding parental strains. (A) Representative plot of one of three biological duplicate outgrowth experiments. (B) Quantitative analysis of lifespan from the outgrowth data seen in panel A. The time (in days) it took for each strain to drop to 10%, 1%, and 0.1% viability was calculated (see Materials and Methods) from two or three independent assays, whenever data available. Some thus did not yield a standard deviation. The lifespan changes of the tor1Δ, ras2Δ, and sod2Δ strains were differences (days to reach 10%, 1%, and 0.1% viability) from the corresponding parental strains. Asterisks (*) indicate that at least one of the two strains being compared maintained the viability higher than 1% or 0.1% throughout the duration of the experiments.

TAG is required for achieving full replicative potential

Like CLS, replicative lifespan of budding yeast is another model for cellular senescence, which is determined as the number of daughters produced by a mother cell during its lifespan [48]. One fundamental difference between chronological and replicative lifespan is that the ability to proliferate is measured from cells sampled from saturation versus logarithmic growth, respectively (Fig 8A). Intriguingly, log phase yeast cells, which allocate most fatty acids to phospholipid synthesis to support cell growth and division, store very little TAG [6]. Although TAG is dispensable for cell survival [10] (Fig 2), the immediate precursor for TAG, diacylglycerol, also supplies building blocks for phospholipids [59]. It is possible that changes in the flux of the albeit small amount of TAG in dividing cells may still impact their replicative lifespan by, for example, influencing the metabolism of other lipids derived from DAG.

Fig 8. Full replicative lifespan requires TAG.

(A) Replicative and chronological lifespan examine cells from log and stationary phase, respectively. (B) TAG quantification of strains harvested 12 and 24 hours after inoculation. These cells were at early and late log phase, respectively. The y axis was set at between 0 to 80 ng/million cells to be consistent with other similar Figs and to highlight the low abundance of TAG in log phase cells. (C) 60 to 90 newly divided daughter cells from the indicated strains were compared for their replicative lifespan. Shown are representative results from three biological duplicates. Breslow analysis showed that the RLS of the dga1Δ lro1Δ cells was significantly different from the other two strains (p < 0.0001).

To assess the influence of TAG on replicative lifespan, yMK839 wildtype, dga1Δ lro1Δ, and tgl3Δ strains were subjected to replicative lifespan comparison by the traditional microscopy approach [23]. Deleting the TAG biosynthetic enzymes further diminished the small TAG pool in log phase cells (12-hour post-inoculation, black bars, Fig 8B). Importantly, both maximum and median replicative lifespan were decreased in cells depleted of TAG (Fig 8C). This shortened replicative lifespan likely accounted for the increased population doubling time of dga1Δ lro1Δ cells (Fig 2E). On the other hand, deleting TGL3 had a minimal effect on the TAG level in early log phase cells (12-hour post-inoculation), and the lifespan of tgl3Δ cells also was unchanged (blue cross marker, Fig 8C). Together, these data demonstrate that maintaining a certain amount of TAG, or the ability to synthesize TAG, is required to reach full replicative potential. TAG hydrolysis apparently is not essential for replicative lifespan maintenance.

Discussion

Here we present evidence for a novel pro-longevity function of intracellular TAG in yeast. Deleting TAG lipases or overproducing a DGAT increased TAG accumulation and extended chronological lifespan. Deleting the two TAG biosynthetic enzymes practically eliminated TAG and significantly shortened the chronological lifespan, as well as the median and maximum replicative lifespan. The fact that chronological lifespan extension is seen in different lipase knockout (i.e., tgl3Δ, tgl4Δ, and tgl3Δ tgl4Δ) and in DGAT overexpression strains argues strongly that the accumulation of TAG was the contributing factor for lifespan extension. This conclusion is consistent with the observation that deleting TGL3 cannot rescue the early death phenotype of dga1Δ lro1Δ lean cells (rows 5 and 6, S5 Fig). Unlike other lifespan extension regimes such as SCH9 knockout and rapamycin treatment that also retard mitotic growth [60, 61], we have yet to detect obvious growth defects in the three lipase deletion strains. For example, aside from normal, or even faster growth rates (Fig 2E), mating and sporulation efficiency of these fat cells was essentially identical to their wildtype mother strain (S3A and S3B Fig). There were no significant differences in cellular sensitivity to heat (55°C), 260 nm UV, high concentrations of NaCl, or to H2O2 (S4 Fig). It is perceivable that a negative phenotype would be linked to TAG lipase null cells if they were grown without any fatty acid supplement, and with concomitant presence of a fatty acid synthase inhibitor such as cerulenin [62]. These cells would suffer from the lack of energy and fatty acid building blocks for growth and division. TAG hydrolysis is thus by and large dispensable as long as fatty acids are available from the environment or can be synthesized by de novo activities. It should be noted that Daum and colleagues reported that tgl3- homozygous knockout cells were unable to form spores [18]. Possible causes for this discrepancy may include differences in the genetic background of the strains, and the protocols for sporulation.

Chronological lifespan of S. cerevisiae is regulated by both yeast-specific and conserved factors and drugs. Experimental results shown in Figs 4 to 7 strongly suggest that TAG preserves viability during chronological senescence in a manner that is independent of those factors tested herein, including caloric restriction, high osmolarity, medium pH, rapamycin and paraquat responses, and conserved pathways involving TOR1, RAS2, and SOD2 genes. Results from genetic interaction tests also suggest a novel TAG pathway in CLS control. Both fat and lean strains responded similarly to the deletion of TOR1, RAS2, or SOD2 (Fig 7), indicating that changes in TAG metabolism does not affect the function of these conserved CLS regulators. Intriguingly, deleting TOR1 shortens the lifespan of both lipase-null and DGAT-deficient cells (Fig 7) but, as expected, protects those cells possessing the normal TAG metabolic capacity. We suggest that tor1Δ cells that survive on the caloric restriction pathway through chronological aging [23, 28] need to tap into the energy depot of TAG. Without TAG biosynthetic enzymes or TAG hydrolytic lipases perturbs this energy flux, thus resulting in early death of tor1Δ cells. In addition to TOR1 and RAS2, we have also combined tgl3Δ and sch9Δ mutations. Deleting SCH9, the ribosome S6 kinase homologue, has been shown to activate the Rim15-Msn2/4 and superoxide dismutase (SOD) stress pathways and prolongs lifespan significantly [29, 63]. Our tests of the genetic interaction between TGL3 and SCH9 were inconclusive. Independent tgl3Δ sch9Δ isolates showed mixed results, ranging from longer CLS to synthetic sickness (S6 Fig). The reason for the stochastic phenotypes is unclear.

Taking into account the observations presented above as well as from previous reports, we hypothesize that TAG has a role in stress response that underlies the observed phenotypes in chronological aging. Firstly, TAG accumulates when yeast cells enter stationary phase in which nutrients are becoming progressively limited [6, 47]. Starvation and stress-induced TAG accumulation appears to be a widespread response in different organisms, including photosynthetic algae [2–4, 64] and animals as well [65–67]. Dietary restriction has been suggested to prolong lifespan by eliciting cellular stress response [31]. Intriguingly, laboratory mice [5] and developing Caenorhabditis elegans [68] have an increased body fat mass when subjected to dietary restriction. Secondly, wild yeast strains in general exhibit higher TAG content and longer chronological lifespan (Fig 1). Food shortage is a common environmental crisis in the wild, but rarely a relevant factor for lab strains. A systematic phenotypic and transcriptomic survey of wild and laboratory strains showed that the latter are less tolerant of many environmental stresses [44]. Certain traits, including stress responses and high levels of TAG, might have lost during the domestication of S. cerevisiae in laboratory environments, in which the selection pressure for long-living, stress-tolerant stationary phase cells is low. It seems plausible that besides preserving energy to cope with uncertainties in food supply, the increased fat content in stressed cells may confer an additional, energy-independent function that helps sustain longevity.

The presumptive stress antagonized by TAG in post-mitotic cells remains to be identified. One candidate is fatty acid-solicited lipotoxicity [69]. Sequestering fatty acids in the form of TAG may prevent lipotoxicity that erodes replicative potential and chronological viability. Disabling TAG biosynthesis results in surplus fatty acids, which may arise from de novo synthesis, uptake from environment, or from lipolysis, that may disrupt membrane lipid homeostasis [9]. Indeed, in an extreme situation where the ability to incorporate fatty acids to TAG and SE is altogether eliminated, yeast cells become hypersensitive to fatty acids and die with membrane hyper-proliferation [12]. Similarly, the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe dga1+ and plh1+ double knockout cells (equivalent to the dga1Δ lro1Δ strain of S. cerevisiae) also die upon entering stationary phase, and are hypersensitive to exogenous fatty acids during vegetative growth [70]. While this lipotoxicity model explains the early death phenotype of dga1Δ lro1Δ cells, total lipid analysis of our long-living fat cells failed to detect significant changes in free fatty acids or DAG (see, for example, Fig 3A). While we cannot rule out the possibility that a small but critical change in certain lipid species contributes more critically to lifespan extension, other hypotheses are worth considering.

One frequently cited cause of aging is mitochondrial dysfunction that also involves oxidative damages [71]. While subcellular compartmentalization confines TAG synthesis and storage to ER and lipid droplets, respectively, a number of reports have demonstrated physical association of mitochondria with ER and LD [72], lending support for functional crosstalk between neutral lipid metabolism and mitochondria biogenesis [73]. Moreover, mitochondria also possess a type II fatty acid synthesis pathway [74]. Deleting enzymes within this pathway causes mouse embryonic lethality and yeast respiratory defects [75, 76]. Fatty acids trafficking between mitochondria and LD may help achieve mitochondrial lipid homeostasis. Importantly, mitochondria are a major source for reactive oxygen species. Free radicals that would otherwise escape from mitochondria and cause pleiotropic cellular damages might enter LD and attack the fatty acyl chains of the storage TAG molecules [77]. It is possible that the high density of peroxidated fatty acids in LD facilitates crosslinking of neighboring radicalized molecules, hence terminating the vicious propagation of radicals. This “radicals sink” model appears to be consistent with the experimental findings presented above.

TAG metabolism and many aspects of cellular aging are conserved. It is thus possible that the cytoprotective role of TAG also exists in higher organisms. For example, Bailey et al. recently reported an anti-oxidant role of lipid droplets in the stem cell niche of Drosophila during neurodevelopment by limiting the levels of reactive oxygen species and inhibiting the oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids [78]. In transgenic mice, overexpression of DGAT1 in the skeletal muscle and heart increased intracellular TAG abundance as well as insulin sensitivity of the underlying animals [79, 80]. Similarly, deleting adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) protected animals from high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance [81]. However, excessive TAG in heart muscle resulting from ATGL knockout also was associated with cardiac dysfunction [73, 82]. These transgenic animal studies underscore the complexity of mammalian metabolism and the interdigitating relationships between triglycerides (dietary, circulating, and in different tissues) and other nutrients. While the positive influence of intracellular TAG on chronological lifespan in yeast is reminiscent of the so-called obesity paradox in humans, that is, the overweight population has the lowest mortality under a number of medical conditions [83, 84], we caution that the comparatively simple yeast may not be immediately applicable to the complex human system. An integrative strategy combining metabolomics, lipidomics, and transcriptomics of representative yeast strains will help elucidate the molecular basis of this novel function of TAG, which might provide a toolbox for a better understanding of the benefits of intracellular TAG in humans.

Materials and Methods

Strains and media

Yeast strains used in this study are shown in Table 1. YPD medium contained 2% glucose (Sigma-Aldrich) (unless otherwise stated in the text), 2% peptone (BD Difco), and 1% yeast extract (BD Difco). SC medium (synthetic complete) contained 2% glucose, 5 g/l ammonium sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich), 1.7 g/l yeast nitrogen base without amino acids or ammonium sulfate (BD Difco), and complete amino acids as described in [85]. Auxotrophic nutrients were supplied at four-fold excess as recommended [23]. Citrate phosphate buffering was done as described [27]. Rapamycin (Sigma-Aldrich) and paraquat dichloride (Fluka) were added from 10 μM and 250 mM stocks to SC medium to make final concentrations of 10 nM and 10 mM, respectively.

Table 1. Yeast strains used in this study.

| Strains | Relevant genotypes | Sources or references |

|---|---|---|

| yMK839 | MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 | [45] |

| yXL004 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 tgl3Δ:: TRP1 | [2] |

| yXL001 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 tgl4Δ:: TRP1 | [2] |

| yXL005 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 tgl3Δ:: KanMX; tgl4Δ:: TRP1 | [2] |

| yXL172 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 ura3-52 dga1Δ:: KanMX; lro1Δ:: URA3 | This study |

| yWH001 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 tgl3Δ:: TRP1; dga1Δ:: KanMX; lro1Δ:: URA3 | This study |

| yXL023 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 pMK595 [2μ URA3] | [2] |

| yXL041 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 tgl3Δ:: TRP1 pMK595 [2μ URA3] | This study |

| yXL183 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 pMK595-DGA1 [2μ URA3] | This study |

| yWH083 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 pMK595 PDGA1-DGA1 [2μ URA3] | This study |

| yXL180 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 tgl3Δ:: TRP1 pMK595-DGA1 [2μ URA3] | This study |

| yWH087 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 tgl3Δ:: TRP1 pMK595 PDGA1-DGA1 [2μ URA3] | This study |

| W303a | MATa leu2-3,112 trp1-1 can1-100 ura3-1 ade2-1 his3-11,15 | |

| BY4742 | MATα his3Δ 1 leu2Δ 0 lys2Δ 0 ura3Δ 0 | |

| yWH47 | BY4742 with tgl3Δ:: URA3 | This study |

| EJ72 | MATa/α gal- trp1 leu2 ura3-52 his4 | [45] |

| yWH036 | EJ72 with tgl3Δ:: URA3/TGL3 | This study |

| yWH74 | EJ72 with tgl3Δ:: TRP1/tgl3Δ:: TRP1 | This study |

| 70‹ | MAT‹ thr3 met | [96] |

| 227a | MATa lys1 | [96] |

| yXL189 (B454‹; clinical sample) | MAT‹ ho::Hygromycin | This study. Haploid isoform of YJM454 from J. McCusker |

| yXL190 (B653‹; clinical sample) | MAT‹ ho::hisG lys2 gal2 | This study. YJM128 [ |

| yXL191 (B756‹; clinical sample) | MAT‹ ho::KanMX6 | This study. Haploid isoform of YJM450 from J. McCusker |

| yXL192 (B779‹; clinical sample) | MAT‹ ho::KanMX6 | This study. Haploid isoform of YJM326 from J. McCusker |

| yXL193 (B359‹; vineyard) | MAT‹ ho::KanMX6 | This study. Haploid isoform of YCD51-4 from Burgundy region of France, 1948 |

| yXL194 (B370‹; vineyard) | MAT‹ ho::KanMX6 | This study. Haploid isoform of M5-2 from Italy in 1993 by R. Mortimer |

| yXL195 (B357‹; oak exudate) | MAT‹; ho::KanMX6 | This study. Haploid isoform of YPS1009-2 from Mettler’s Woods, New Jersey in 2000 by P. Sniegowski |

| yXL196 (B390‹; oak exudate) | MAT‹ ho::KanMX6 | This study. Haploid isoform of YPS1000-1 from Mettler’s Woods, New Jersey in 2000 by P. Sniegowski |

| yXD188 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 tor1Δ:: URA3 | This study |

| yXD189 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 ras2Δ:: URA3 | This study |

| yXD190 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 sod2Δ:: URA3 | This study |

| yXD191 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 tgl3Δ:: TRP1; tor1Δ:: URA3 | This study |

| yXD192 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 tgl3Δ:: TRP1; ras2Δ:: URA3 | This study |

| yXD193 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 tgl3Δ:: TRP1; sod2Δ:: URA3 | This study |

| yXD200 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 dga1Δ:: KanMX; lro1Δ:: TRP1 | This study |

| yXD201 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 dga1Δ:: KanMX; lro1Δ:: TRP1; tor1Δ:: URA3 | This study |

| yXD202 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 dga1Δ:: KanMX; lro1Δ:: TRP1; ras2Δ:: URA3 | This study |

| yXD203 | From yMK839 MATa leu2-3 trp1 ura3-52 dga1Δ:: KanMX; lro1Δ:: TRP1; sod2Δ:: URA3 | This study |

Yeast methods

Yeast transformation was performed using the lithium acetate method [86]. Deletion of TGL3 and TGL4 was described in [2]. To delete DGA1, PCR reactions using primers ATGTCAGGAACATTCAATGATATAAGAAGAAGGAAGAAGGAAGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA and TTACCCAACTATCTTCAATTCTGCATCCGGTACCCCATATTTATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC and template pFA6a-KanMX6 [87] were conducted. To delete LRO1, primers TATCCATATGACGTTCCAGATTACGCTGCTCAGTGCGGCCGCATGTCAGGAACATTCAAT and GAATTTCGACGGTATCGGGGGGATCCACTAGTTCTAGCTAGATTACCCAACTATCTTCAA were used with pBS1539 as the template to amplify K. lactis URA3 gene as the selective marker [88]. To delete TOR1, primers GAACCGCATGAGGAGCAGATTTGGAAGAGTAAACTTTTGAAATGAAGCTTGATATCGAAT and CCAGAATGGGCACCATCCAATATAATGTTGACATAACCTTTCTACGACTCACTATAGGGC were used with pBS1539 to amplify K. lactis URA3. For RAS2 deletion, primers CCTTTGAACAAGTCGAACATAAGAGAGTACAAGCTAGTCGTCTGAAGCTTGATATCGAAT and ACTTATAATACAACAGCCACCCGATCCGCTCTTGGAGGCTTCTACGACTCACTATAGGGC were used to amplify K. lactis URA3 on pBS1539. For SOD2 deletion, primers TTCGCGAAAACAGCAGCTGCTAATTTAACCAAGAAGGGTGGTTGAAGCTTGATATCGAAT and GATCTTGCCAGCATCGAATCTTCTGGATGCTTCTTTCCAGTTTACGACTCACTATAGGGC were used to amplify K. lactis URA3 on pBS1539. The PCR products were gel-purified for yeast transformation. Genomic PCR was used to verify the correct insertion. To overproduce Dga1p, a yeast genomic PCR product was co-transformed with Not I-linearlized pMK595 [89] for ADH1-controlled expression (pMK595-DGA1). A second multicopy DGA1 overexpression plasmid with DGA1 under its own promoter control (pMK595 PDGA1-DGA1) was constructed similarly, except that the DGA1 promoter (961 bp) was included in the transforming PCR DNA, using primers ATCCATATGACGTTCCAGATTACGCTGCTCAGTGCGGGTAAAGAATCTAAATCGAGCTAC and atcggggggatccactagttctagctagagcggccTAGATAGGTACAATCGACTTAAAGC.

The tgl3Δ /tgl3Δ diploid strain yWH74 was generated by first transforming yXL004 with YCp50-HO [90] to induce mating type switch and subsequently spontaneous mating of cells in the same colony. Homozygous diploid cells were identified by their inability to mate as either a MATa and MATalpha strain. Diploid cells were then grown in YPD for two days to allow for the loss of YCp50-HO, resulting in 5-FOA resistant, ura3- cells.

For growth curve analyses, yeast cells were seeded at an initial concentration of 0.1 OD600 in 150 μl of YPD medium in 96-well plates with biological and technical duplicates. The plates were examined by measuring OD630 every 30 minutes via a BioTex PowerWave XS plate reader until cells reached saturation. The machine was programmed to shake at the high-speed setting and to control temperature at 30°C.

Lifespan analyses

Chronological lifespan was measured by the outgrowth method as described in [85]. Briefly, yeast from stab cultures were inoculated to YPD broth and grown at 30°C overnight or until late log phase. Cultures were then diluted into 5 ml SC medium at 0.1 OD600. The seeded cultures, in 15-ml glass tubes with a loose metal cap, were incubated in a rotator drum at 30°C. At selected time points, 5 μl of stationary phase cultures were sampled out and mixed with 145 μl of fresh liquid YPD in a 96-well plate. The plates were sealed with parafilm to prevent evaporation, and incubated in the BioTex PowerWave XS plate reader. Cell density (OD630) was monitored every 30 minute for 48 hours. Growth curves, doubling times, and survival fractions were calculated according to [85]. To compare the quantitative differences in lifespan of different strains, the time by which each culture reached 10%, 1%, and 0.1% survival fractions was obtained from three independent survival curves. The cultures which survived beyond 30 days before reaching the specified survival fractions were not included in the statistical calculation and represented as >30 days.

For spot assays, stationary phase cultures at selective time points were adjusted to 1 OD600 with sterile water in 96-well plates and ten-fold serially diluted. 5 μl of cells from each well were spotted to a YPD plate and grown at 30°C for two days. The culture viability was quantified by counting visible colonies at the most diluted spot. The number of colonies multiplied by the dilution factor of that spot was regarded as the viability. This method was adapted from the Tadpole assay as described in [91].

Replicative lifespan was performed according to previously described [92] by counting number of progeny produced by 60–90 virgin cells from young mother of each strain. Daughter cells were removed every 90 minutes by a micromanipulator. The lifespan analyses were performed by using R software, version 3.0.3 with survival and KMsurv packages. Breslow test was used for statistic analysis.

Lipid analysis and Nile red staining

Total lipid extraction was conducted essentially as described before [70] with modifications. Briefly, 3 OD600 cells from selected time points were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 5 minutes at room temperature, followed by washing once with 1 ml water, and were kept at -80°C if lipid extraction was not done immediately after cell collection. To extract total lipids, cells, if frozen, were removed from the freezer and mixed directly with 300 μl of glass beads (425–600 μm, Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 ml of chloroform: methanol (17:1, v/v) (JT Baker) by vortexing twice for 90 seconds at 4°C. The mixtures were briefly spun and the supernatant was moved to a new glass tube. The remaining cell debris and glass beads were vortexed with an additional 1 ml of chloroform: methanol (2:1, v/v). The supernatant was collected as above and pooled with the previous fraction. 1 ml of 0.2 M phosphoric acid and 1 M KCl, was added to the pooled organic fraction and vortexed vigorously for 30 seconds, and spun at 3,000 rpm, 4°C for 5 minutes to separate the organic and aqueous phases. The chloroform phase at the bottom was collected and dried under nitrogen gas. This lipid extract served as the total lipid fraction. To purify TAG, total lipids were developed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on a G60 silica plate (EMD Chemicals). The mobile phase was composed of petroleum ether (35–60°C, Macron): diethyl ether (JT Baker): acetic acid (JT Baker) = 80: 20: 1 (v/v/v). Following development, the TLC plates were briefly stained with iodine vapor to reveal the position of TAG. Spots co-migrating with a TAG control (olive oil, Dante) were isolated and converted to fatty acyl methyl esters (FAME) by reacting with 1 ml of 1 N Methanolic HCl (Sigma-Aldrich) at 80°C for 25 minutes [93]. A universal internal control of 5 μg of pentadecanoic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) was included in all samples for FAME derivatization and gas chromatography (GC). 1 ml of 0.9% NaCl was added to stop the FAME reaction, followed by the addition of 1 ml of hexane, and vortexed for 30 sec to extract FAME. Centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C was conducted before the hexane layer was aspirated to another glass tube, and the volume reduced to 30 μl under nitrogen blowing. 2 μl of the FAME in hexane was injected to a gas chromatography system (Agilent Technology, 7890A) for quantification.

To visualize lipid droplets in yeast cells, approximately 0.5 OD600 cells were collected by centrifugation (14,000 rpm for 1 min in a microfuge) and washed once by 1 ml TE buffer (pH 7.4). Cell pellets were suspended in 100 μl of TE buffer and stained with 1 mg/ml Nile red in the presence of 3.7% formaldehyde for concomitant fixation, and let sit in the dark for 20 min. Cells were collected again by microcentrifugation and re-suspended in 100 μl TE buffer and stored in the dark for no more than two days. For microscopy, an Olympus BX51 station with a Exfo X-cite 120 UV light fixture and a DP30-BW CCD camera were used. A GFP filter was used for lipid droplet fluorescence detection. For semi-quantitative comparison of lipid droplets, a fixed exposure (typically 2 seconds) for fluorescence was applied to all samples.

Sporulation and mating analysis

Sporulation efficiency was determined by microscopically examining the percent of diploid cells forming asci. Overnight YPD cultures of diploid strains were transferred to PSP2 medium (Potassium phthalate (Sigma-Aldrich) 8.3 g/l, yeast extract 1 g/l, 1.7 g/l yeast nitrogen base without amino acids or ammonium sulfate, ammonium sulfate 5 g/l, potassium acetate 10 g/l, pH 5.4 at 0.1 OD600 and grown at 30°C under vigorous shaking (200–250 rpm). After 24 hours, cells were harvested by centrifugation (14,000 rpm, 30 sec in a microfuge), washed once with sterile water, and re-suspended in 1 ml SPM medium (potassium acetate 3 g/l, raffinose 0.2 g/l). Cultures were shaken vigorously at 200–250 rpm at 30°C for 48–72 hours. A small amount of cells were removed from the culture, spun, and suspended in 1 mg/ml DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) in a mounting medium (1 mg/ml p-phenylenediamine, 0.9% glycerol, 2.25 μg/ml DAPI). Percent of cells forming asci with four DAPI foci (i.e., four spores) were counted.

Mating efficiency was quantified by mixing 0.1 OD600 of “tested” strains with 0.5 OD600 of tester strains of the opposite mating type (227a or 70 ‹), all in early log phase, in 1 ml of YPD. Cell mixtures were let sit at 30°C for 5 hours. The tested and tester stains were also incubated separately as the negative control. Cells were washed once with sterile water and plated on SD medium (2% glucose, 1.7 g/l nitrogen base with amino acids or ammonium sulfate, 5 g/l ammonium sulfate, 20 g/l agar). Mating between the tested and tester strains generated prototroph diploid cells that were able to form colonies on the SD medium plate.

Wild strains segregation

The strains B454, B756, B779, B359, B370, B357 and B390 were segregants of isolates collected in the wild (see Table 1 for source and reference). In order to generate isogenic haploid strains, the heterozygous wild isolates were sporulated and self diploidized due to homothallism. We randomly selected one of the four homozygous segregants from each tetrad. Next, strains were made heterothallic via removal of the HO gene, using homologous gene replacement with either a Hgh cassette (pAG32) [94] (strain B454 due to a natural kanamycin resistance) or a KanMX6 cassette (pFA6a) [95] (strains B756, B779, B359, B370, B357 and B390). Transformed strains were sporulated and dissected to verify 2:2 segregation of either hygromycin or kanamycin resistance. One MATa and MATalpha haploid transformant was retained from each strain. Proper integration at the HO locus was verified via PCR. Strain B653 was obtained from John McCusker.

Supporting Information

5-day old stationary phase cultures were harvested for neutral lipid staining with Nile red. DIC (differential interference contrast) and fluorescence microscopy were done using an Olympus BX51 station equipped with a Exfo X-cite 120 UV light fixture and a DP30-BW CCD camera. Fluorescence micrographs were taken with a fixed, 2-second exposure to aid comparison of the fluorescence intensity. Scale bars: 5 μm. All pictures were re-sized identically for presentation.

(TIF)

Total TAG, expressed as percentage of total cellular lipids, of wildtype, tgl3Δ, tgl4Δ, and tgl3Δ tgl4Δ strains were isolated and quantified by gas chromatography. Cells were from 3-day old YPD cultures. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01

(TIF)

(A) Haploid strains, as indicated, were tested for their mating efficiency with a tester strain. (B) TGL3 +/+ and -/- diploid strains were subjected to sporulation. 3 days after transferring cells to the sporulation medium, cells were examined under a microscope to quantify for the number of tetrads.

(TIF)

Day 3 early-stationary phase cultures were exposed to the shown stresses before plating to YPD. For the test of salt sensitivity, NaCl (0.7 or 1.4 M) was included in the YPD plate. Heat and H2O2 sensitivity were conducted by exposing cell suspension (after water wash for H2O2) to the stress before serially diluted for plating. For UV exposure, serially diluted cells were spotted to YPD before UV exposure. The plates were incubated in dark afterwards.

(TIF)

The indicated strains (on the right) were grown in SC with 2% glucose and sampled at the indicated time for semi-quantitative comparison of colony forming units. 10-fold serially diluted cell suspension was spotted to YPD.

(TIFF)

SCH9 was deleted from TGL3+ and tgl3Δ backgrounds for chronological lifespan assessment. Two independent tgl3Δ sch9Δ transformation colonies were isolated and tested. Both were ›+, but one apparently was synthetic sick while the other exhibited normal growth and extended lifespan. Shown are representative results of two independent SCH9 knockout attempts.

(TIFF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Zhiying You for assisting statistical analysis; Eve Gardner, Jaikishan Prasad, Rachel Green, Hao Nguyen, Jan Stoltin, and Rebecca Roston for technical assistance; and Kelly Tatchell and Paul Siliciano for tracing the history of yMK839 and EG123. Barbara Sears, Astrid Vieler, and Neil Bowlby are thanked for their advice on TAG analysis. We acknowledge Erik Martinez-Hackert, David Arnosti, Tom Sharkey, and John Wang for their critical reading and suggestions for this manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

WH was supported by the Royal Government of Thailand Scholarship for Development and Promotion of Science and Technology and subsidized by NSF MCB1050132; XL was partially supported by a fund from the GEDD Focus Group, MSU. The work on TAG biosynthesis in the Benning lab was supported by a Department of Energy–Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center Cooperative Agreement DE-FC02-07ER6449. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Murphy DJ. The dynamic roles of intracellular lipid droplets: from archaea to mammals. Protoplasma. 2012;249(3):541–85. 10.1007/s00709-011-0329-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li X, Benning C, Kuo MH. Rapid triacylglycerol turnover in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii requires a lipase with broad substrate specificity. Euk Cell. 2012;11(12):1451–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cakmak ZE, Olmez TT, Cakmak T, Menemen Y, Tekinay T. Induction of triacylglycerol production in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: comparative analysis of different element regimes. Bioresour Technol. 2014;155:379–87. 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.12.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pal D, Khozin-Goldberg I, Cohen Z, Boussiba S. The effect of light, salinity, and nitrogen availability on lipid production by Nannochloropsis sp. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;90(4):1429–41. Epub 2011/03/25. 10.1007/s00253-011-3170-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li X, Cope MB, Johnson MS, Smith DL Jr, Nagy TR. Mild Calorie Restriction Induces Fat Accumulation in Female C57BL/6J Mice. Obesity. 2009;18(3):456–62. 10.1038/oby.2009.312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor FR, Parks LW. Triaglycerol metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Relation to phospholipid synthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;575(2):204–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daum G, Wagner A, Czabany T, Athenstaedt K. Dynamics of neutral lipid storage and mobilization in yeast. Biochimie. 2007;89(2):243–8. Epub 2006/08/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oelkers P, Tinkelenberg A, Erdeniz N, Cromley D, Billheimer JT, Sturley SL. A lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase-like gene mediates diacylglycerol esterification in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(21):15609–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oelkers P, Cromley D, Padamsee M, Billheimer JT, Sturley SL. The DGA1 gene determines a second triglyceride synthetic pathway in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(11):8877–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandager L, Gustavsson MH, Stahl U, Dahlqvist A, Wiberg E, Banas A, et al. Storage lipid synthesis is non-essential in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(8):6478–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fenner GP, Parks LW. Gas chromatographic analysis of intact steryl esters in wild type Saccharomyces cerevisiae and in an ester accumulating mutant. Lipids. 1989;24(7):625–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petschnigg J, Wolinski H, Kolb D, Zellnig G, Kurat CF, Natter K, et al. Good fat, essential cellular requirements for triacylglycerol synthesis to maintain membrane homeostasis in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(45):30981–93. 10.1074/jbc.M109.024752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welte MA. Expanding Roles for Lipid Droplets. Curr Biol. 2015;25(11):R470–R81. Epub 2015/06/03. 10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radulovic M, Knittelfelder O, Cristobal-Sarramian A, Kolb D, Wolinski H, Kohlwein SD. The emergence of lipid droplets in yeast: current status and experimental approaches. Curr Genet. 2013;59(4):231–42. 10.1007/s00294-013-0407-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodges BD, Wu CC. Proteomic insights into an expanded cellular role for cytoplasmic lipid droplets. J Lipid Res. 2010;51(2):262–73. Epub 2009/12/08. 10.1194/jlr.R003582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ploier B, Scharwey M, Koch B, Schmidt C, Schatte J, Rechberger G, et al. Screening for hydrolytic enzymes reveals Ayr1p as a novel triacylglycerol lipase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(50):36061–72. Epub 2013/11/05. 10.1074/jbc.M113.509927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmermann R, Strauss JG, Haemmerle G, Schoiswohl G, Birner-Gruenberger R, Riederer M, et al. Fat mobilization in adipose tissue is promoted by adipose triglyceride lipase. Science. 2004;306(5700):1383–6. Epub 2004/11/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Athenstaedt K, Daum G. Tgl4p and Tgl5p, two triacylglycerol lipases of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae are localized to lipid particles. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(45):37301–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurat CF, Wolinski H, Petschnigg J, Kaluarachchi S, Andrews B, Natter K, et al. Cdk1/Cdc28-dependent activation of the major triacylglycerol lipase Tgl4 in yeast links lipolysis to cell-cycle progression. Mol Cell. 2009;33(1):53–63. Epub 2009/01/20. 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koffel R, Tiwari R, Falquet L, Schneiter R. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae YLL012/YEH1, YLR020/YEH2, and TGL1 genes encode a novel family of membrane-anchored lipases that are required for steryl ester hydrolysis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(5):1655–68. Epub 2005/02/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koffel R, Schneiter R. Yeh1 constitutes the major steryl ester hydrolase under heme-deficient conditions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5(7):1018–25. Epub 2006/07/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaeberlein M. Lessons on longevity from budding yeast. Nature. 2010;464(7288):513–9. Epub 2010/03/26. 10.1038/nature08981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Longo VD, Shadel GS, Kaeberlein M, Kennedy B. Replicative and chronological aging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Metab. 2012;16(1):18–31. 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herman PK. Stationary phase in yeast. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2002;5(6):602–7. Epub 2002/11/30. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen C, Buttner S, Aragon AD, Thomas JA, Meirelles O, Jaetao JE, et al. Isolation of quiescent and nonquiescent cells from yeast stationary-phase cultures. J Cell Biol. 2006;174(1):89–100. Epub 2006/07/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Werner-Washburne M, Roy S, Davidson GS. Aging and the Survival of Quiescent and Non-quiescent Cells in Yeast Stationary-Phase Cultures. Subcell Biochem. 2012;57:123–43. Epub 2011/11/19. 10.1007/978-94-007-2561-4_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burtner CR, Murakami CJ, Kennedy BK, Kaeberlein M. A molecular mechanism of chronological aging in yeast. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(8):1256–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei M, Fabrizio P, Madia F, Hu J, Ge H, Li LM, et al. Tor1/Sch9-regulated carbon source substitution is as effective as calorie restriction in life span extension. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(5):e1000467 Epub 2009/05/09. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fabrizio P, Pozza F, Pletcher SD, Gendron CM, Longo VD. Regulation of longevity and stress resistance by Sch9 in yeast. Science. 2001;292(5515):288–90. Epub 2001/04/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Longo VD. Mutations in signal transduction proteins increase stress resistance and longevity in yeast, nematodes, fruit flies, and mammalian neuronal cells. Neurobiol Aging. 1999;20(5):479–86. Epub 2000/01/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sinclair DA. Toward a unified theory of caloric restriction and longevity regulation. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126(9):987–1002. Epub 2005/05/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mirisola MG, Taormina G, Fabrizio P, Wei M, Hu J, Longo VD. Serine- and threonine/valine-dependent activation of PDK and Tor orthologs converge on Sch9 to promote aging. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(2):e1004113 Epub 2014/02/12. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Longo VD, Gralla EB, Valentine JS. Superoxide dismutase activity is essential for stationary phase survival in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mitochondrial production of toxic oxygen species in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(21):12275–80. Epub 1996/05/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonawitz ND, Rodeheffer MS, Shadel GS. Defective mitochondrial gene expression results in reactive oxygen species-mediated inhibition of respiration and reduction of yeast life span. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(13):4818–29. Epub 2006/06/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schroeder EA, Shadel GS. Crosstalk between mitochondrial stress signals regulates yeast chronological lifespan. Mech Ageing Dev. 2014;135:41–9. Epub 2014/01/01. 10.1016/j.mad.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carmona-Gutierrez D, Eisenberg T, Buttner S, Meisinger C, Kroemer G, Madeo F. Apoptosis in yeast: triggers, pathways, subroutines. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17(5):763–73. Epub 2010/01/16. 10.1038/cdd.2009.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weinberger M, Feng L, Paul A, Smith DL Jr., Hontz RD, Smith JS, et al. DNA replication stress is a determinant of chronological lifespan in budding yeast. PLoS One. 2007;2(1):e748. Epub 2007/08/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldberg AA, Bourque SD, Kyryakov P, Gregg C, Boukh-Viner T, Beach A, et al. Effect of calorie restriction on the metabolic history of chronologically aging yeast. Exp Gerontol. 2009;44(9):555–71. Epub 2009/06/23. 10.1016/j.exger.2009.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith ED, Tsuchiya M, Fox LA, Dang N, Hu D, Kerr EO, et al. Quantitative evidence for conserved longevity pathways between divergent eukaryotic species. Genome Res. 2008;18(4):564–70. Epub 2008/03/15. 10.1101/gr.074724.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Powers RW 3rd, Kaeberlein M, Caldwell SD, Kennedy BK, Fields S. Extension of chronological life span in yeast by decreased TOR pathway signaling. Genes Dev. 2006;20(2):174–84. Epub 2006/01/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matecic M, Smith DL, Pan X, Maqani N, Bekiranov S, Boeke JD, et al. A microarray-based genetic screen for yeast chronological aging factors. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(4):e1000921 Epub 2010/04/28. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burtner CR, Murakami CJ, Olsen B, Kennedy BK, Kaeberlein M. A genomic analysis of chronological longevity factors in budding yeast. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(9):1385–96. Epub 2011/03/31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liti G, Louis EJ. Advances in quantitative trait analysis in yeast. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(8):e1002912 Epub 2012/08/24. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kvitek DJ, Will JL, Gasch AP. Variations in stress sensitivity and genomic expression in diverse S. cerevisiae isolates. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(10):e1000223 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siliciano PG, Tatchell K. Transcription and regulatory signals at the mating type locus in yeast. Cell. 1984;37(3):969–78. Epub 1984/07/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murakami CJ, Burtner CR, Kennedy BK, Kaeberlein M. A method for high-throughput quantitative analysis of yeast chronological life span. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(2):113–21. Epub 2008/03/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gray JV, Petsko GA, Johnston GC, Ringe D, Singer RA, Werner-Washburne M. "Sleeping beauty": quiescence in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68(2):187–206. Epub 2004/06/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mortimer RK, Johnston JR. Life span of individual yeast cells. Nature. 1959;183(4677):1751–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fabrizio P, Longo VD. The chronological life span of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Aging Cell. 2003;2(2):73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Athenstaedt K, Daum G. YMR313c/TGL3 encodes a novel triacylglycerol lipase located in lipid particles of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(26):23317–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kurat CF, Natter K, Petschnigg J, Wolinski H, Scheuringer K, Scholz H, et al. Obese yeast: triglyceride lipolysis is functionally conserved from mammals to yeast. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(1):491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumar S, Kawalek A, van der Klei IJ. Peroxisomal quality control mechanisms. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2014;22:30–7. 10.1016/j.mib.2014.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loewith R, Hall MN. Target of rapamycin (TOR) in nutrient signaling and growth control. Genetics. 2011;189(4):1177–201. 10.1534/genetics.111.133363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mirisola MG, Longo VD. Acetic acid and acidification accelerate chronological and replicative aging in yeast. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(19):3532–3. 10.4161/cc.22042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burhans WC, Weinberger M. Acetic acid effects on aging in budding yeast: are they relevant to aging in higher eukaryotes? Cell Cycle. 2009;8(14):2300–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Longo VD. Ras: the other pro-aging pathway. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2004;2004(39):pe36 Epub 2004/10/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garay E, Campos SE, Gonzalez de la Cruz J, Gaspar AP, Jinich A, Deluna A. High-resolution profiling of stationary-phase survival reveals yeast longevity factors and their genetic interactions. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(2):e1004168 Epub 2014/03/04. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Unlu ES, Koc A. Effects of deleting mitochondrial antioxidant genes on life span. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1100:505–9. Epub 2007/04/27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carman GM, Han GS. Regulation of phospholipid synthesis in yeast. J Lipid Res. 2009;50 Suppl:S69–73. Epub 2008/10/29. 10.1194/jlr.R800043-JLR200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Neklesa TK, Davis RW. Superoxide anions regulate TORC1 and its ability to bind Fpr1:rapamycin complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105(39):15166–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Toda T, Cameron S, Sass P, Wigler M. SCH9, a gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae that encodes a protein distinct from, but functionally and structurally related to, cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunits. Genes Dev. 1988;2(5):517–27. Epub 1988/05/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nomura S, Horiuchi T, Omura S, Hata T. The action mechanism of cerulenin. I. Effect of cerulenin on sterol and fatty acid biosynthesis in yeast. J Biochem. 1972;71(5):783–96. Epub 1972/05/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fabrizio P, Liou LL, Moy VN, Diaspro A, Valentine JS, Gralla EB, et al. SOD2 functions downstream of Sch9 to extend longevity in yeast. Genetics. 2003;163(1):35–46. Epub 2003/02/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vieler A, Wu G, Tsai CH, Bullard B, Cornish AJ, Harvey C, et al. Genome, functional gene annotation, and nuclear transformation of the heterokont oleaginous alga Nannochloropsis oceanica CCMP1779. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(11):e1003064 Epub 2012/11/21. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khatchadourian A, Bourque SD, Richard VR, Titorenko VI, Maysinger D. Dynamics and regulation of lipid droplet formation in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated microglia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821(4):607–17. Epub 2012/02/01. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Younce C, Kolattukudy P. MCP-1 induced protein promotes adipogenesis via oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;30(2):307–20. Epub 2012/06/29. 10.1159/000339066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee SJ, Zhang J, Choi AM, Kim HP. Mitochondrial dysfunction induces formation of lipid droplets as a generalized response to stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:327167 Epub 2013/11/01. 10.1155/2013/327167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Palgunow D, Klapper M, Doring F. Dietary restriction during development enlarges intestinal and hypodermal lipid droplets in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e46198 10.1371/journal.pone.0046198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schrauwen P, Schrauwen-Hinderling V, Hoeks J, Hesselink MK. Mitochondrial dysfunction and lipotoxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801(3):266–71. Epub 2009/09/29. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang Q, Chieu HK, Low CP, Zhang S, Heng CK, Yang H. Schizosaccharomyces pombe cells deficient in triacylglycerols synthesis undergo apoptosis upon entry into the stationary phase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(47):47145–55. Epub 2003/09/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bonawitz ND, Shadel GS. Rethinking the mitochondrial theory of aging: the role of mitochondrial gene expression in lifespan determination. Cell Cycle. 2007;6(13):1574–8. Epub 2007/07/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barbosa AD, Savage DB, Siniossoglou S. Lipid droplet-organelle interactions: emerging roles in lipid metabolism. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2015;35:91–7. Epub 2015/05/20. 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Haemmerle G, Moustafa T, Woelkart G, Buttner S, Schmidt A, van de Weijer T, et al. ATGL-mediated fat catabolism regulates cardiac mitochondrial function via PPAR-alpha and PGC-1. Nat Med. 2011;17(9):1076–85. Epub 2011/08/23. 10.1038/nm.2439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hiltunen JK, Schonauer MS, Autio KJ, Mittelmeier TM, Kastaniotis AJ, Dieckmann CL. Mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis type II: more than just fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(14):9011–5. Epub 2008/11/26. 10.1074/jbc.R800068200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yi X, Maeda N. Endogenous production of lipoic acid is essential for mouse development. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(18):8387–92. Epub 2005/09/02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kastaniotis AJ, Autio KJ, Sormunen RT, Hiltunen JK. Htd2p/Yhr067p is a yeast 3-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase essential for mitochondrial function and morphology. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53(5):1407–21. Epub 2004/09/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Niki E. Lipid peroxidation: physiological levels and dual biological effects. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47(5):469–84. Epub 2009/06/09. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bailey AP, Koster G, Guillermier C, Hirst EM, MacRae JI, Lechene CP, et al. Antioxidant Role for Lipid Droplets in a Stem Cell Niche of Drosophila. Cell. 2015;163(2):340–53. Epub 2015/10/10. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu L, Shi X, Bharadwaj KG, Ikeda S, Yamashita H, Yagyu H, et al. DGAT1 expression increases heart triglyceride content but ameliorates lipotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(52):36312–23. Epub 2009/09/26. 10.1074/jbc.M109.049817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu L, Zhang Y, Chen N, Shi X, Tsang B, Yu YH. Upregulation of myocellular DGAT1 augments triglyceride synthesis in skeletal muscle and protects against fat-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(6):1679–89. Epub 2007/05/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hoy AJ, Bruce CR, Turpin SM, Morris AJ, Febbraio MA, Watt MJ. Adipose triglyceride lipase-null mice are resistant to high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance despite reduced energy expenditure and ectopic lipid accumulation. Endocrinology. 2011;152(1):48–58. Epub 2010/11/26. 10.1210/en.2010-0661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Haemmerle G, Lass A, Zimmermann R, Gorkiewicz G, Meyer C, Rozman J, et al. Defective lipolysis and altered energy metabolism in mice lacking adipose triglyceride lipase. Science. 2006;312(5774):734–7. Epub 2006/05/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Flegal KM, Kit BK, Orpana H, Graubard BI. Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2013;309(1):71–82. 10.1001/jama.2012.113905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lavie CJ, De Schutter A, Milani RV. Healthy obese versus unhealthy lean: the obesity paradox. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11(1):55–62. 10.1038/nrendo.2014.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Murakami C, Kaeberlein M. Quantifying yeast chronological life span by outgrowth of aged cells. J Vis Exp. 2009;(27). Epub 2009/05/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gietz D, Jean A, Woods RA, Schiestl RH. Improved method for high efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20(6):1425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wei W, McCusker JH, Hyman RW, Jones T, Ning Y, Cao Z, et al. Genome sequencing and comparative analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain YJM789. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(31):12825–30. Epub 2007/07/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Markgraf DF, Klemm RW, Junker M, Hannibal-Bach HK, Ejsing CS, Rapoport TA. An ER protein functionally couples neutral lipid metabolism on lipid droplets to membrane lipid synthesis in the ER. Cell Rep. 2014;6(1):44–55. Epub 2014/01/01. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.11.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Luo J, Xu X, Hall H, Hyland EM, Boeke JD, Hazbun T, et al. Histone h3 exerts a key function in mitotic checkpoint control. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(2):537–49. Epub 2009/11/18. 10.1128/MCB.00980-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]