Abstract

Calcineurin heterodimer, comprised of the catalytic (CnaA) and regulatory (CnaB) subunits, localizes at the hyphal tips and septa to direct growth, septation, and disease in the human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Here we discovered a novel motif (FMDVF) required for this critical CnaA septal localization, including residues Phe368, Asp370 and Phe372 overlapping the cyclosporine A-cyclophilin A binding domain, CnaB-binding helix and the FK506-FKBP12 binding pocket. Mutations in adjacent residues Asn367, Trp374 and Ser375 confer FK506 resistance without impacting CnaA septal localization. Modeling A. fumigatus CnaA confirmed that the FMDVF motif forms a bridge between the two known substrate binding motifs, PxIxIT and LxVP, and concurrent mutations (F368A D370A; F368A F372A) in the FMDVF motif disrupt CnaA-substrate interaction at the septum.

Keywords: Aspergillus fumigatus, calcineurin, septum, FK506, PxIxIT motif, LxVP motif

Introduction

Calcineurin is a critical phosphatase required for hyphal growth and virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus [1,2]. As a heterodimer with a catalytic (CnaA) and regulatory (CnaB) subunit, it is activated by calmodulin [3]. CnaB binds to CnaA at the hydrophobic CnaB-binding helical region (CnBBH) between the catalytic domain and the calmodulin-binding domain (CaMBD) [3,4]. Calcineurin is the target of immunosuppressive drugs tacrolimus (FK506) and cyclosporine A (CsA) that bind to CnaA in proximity to the CnBBH in the presence of their respective immunophilins, FKBP12 and cyclophilin A, causing calcineurin inactivation [5]. To date, the only well-characterized motifs involved in calcineurin interaction with its substrates are the PxIxIT and LxVP motifs [6–11]. Recently, the mode of inhibition of calcineurin by the African swine fever virus protein A238L revealed how the immunosuppressants bind to LxVP sequences to inhibit substrate dephosphorylation without occupying the active site, paving the way for designing new calcineurin inhibitors [12].

The current antifungal armamentarium against deadly invasive fungal infections has limited effectiveness. The potential of exploiting the calcineurin signaling network as a novel antifungal target is yet to be harnessed [13,14]. Calcineurin’s importance for cellular processes, including growth, sexual development, pathogenesis and stress-dependent regulation, has been documented in multiple fungi [15–20]. Hyphal growth is required for invasive fungal disease, and our previous studies demonstrated that calcineurin regulates hyphal growth by localizing on either side of the hyphal septum as a disc around the septal pore [21]. We also demonstrated that CnaA septal localization is independent of CnaB-binding [22]. Generation of catalytic null mutants revealed that localization and activity of the calcineurin complex at the hyphal septum is indispensable for hyphal extension [22,23]. Mutation of the PxIxIT-substrate binding motif residues Asn352, Ile353, and Arg354 (352NIR354) in the substrate recognition β strand of CnaA demonstrated that CnaA localizes at the septum through binding to other protein(s) [23]. Identification of other functional domains required for calcineurin septal localization would provide important clues towards the modality of its interaction at the hyphal septum and be useful for designing novel fungal-specific inhibitory strategies.

Results and Discussion

The FMDVF motif is required for localization and function of CnaA at the hyphal septum

The PxIxIT-binding NIR residues (Asn352, Ile353, and Arg354) in CnaA are adjacent to the CnBBH and are part of the CsA-cyclophilin A binding domain (Fig. 1A). Although mutagenesis studies on the calcineurin catalytic subunit from humans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae revealed the importance of Val371, Phe372, Phe378, Val379, and Met386 (amino acids numbered as per A. fumigatus CnaA) for CnaB binding [24,25], the functionality of other residues present upstream and in proximity have never been examined.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic of domains of A. fumigatus calcineurin A: residues in the cyclosporine A-cyclophilin A binding domain (red underline), the FK506-FKBP12 binding domain (blue underline) and the CnaB-binding helix (CnBBH; green underline). PxIxIT-binding NIR residues are in bold and FMDVF motif residues underlined. Catalytic domain is orange, and the remaining C-terminal portion, including the CnBBH, the calmodulin-binding domain (CaMBD) and the autoinhibitory domain (AID), are boxed. (B) Radial growth of the wild-type strain (akuBKU80) and the CnaA FMDVF mutant strains (CnaA-F368A; CnaA-D370A; CnaA-F368A D370A and CnaA-F368A F372A) assessed after 5 days and depicted as mean ± standard deviation. (C) Respective FMDVF mutant strains cultured on coverslips in GMM liquid medium for 18–20 h at 37 °C. Scale bar is 10 μm.

To investigate the importance of conserved residues within the CnBBH overlapping the FK506-binding and CsA-binding domains, we performed single and simultaneous mutations of the Phe368, Asp370 and Phe372 residues in the FMDVF motif (underlined). In comparison to the wild-type strain (akuBKU80), strains expressing the individual mutations (CnaA-F368A or CnaA-D370A) showed a 40–50% reduction in radial growth (Fig. 1B; upper panel). However, simultaneous mutation of two residues (CnaA-F368A D370A or CnaA-F368A F372A) resulted in severe growth inhibition (75%), with maximal growth reduction (87%) in the CnaA-F368A F372A strain (Fig. 1B; lower panel). While the single mutation strains did not show any significant variations in hyphal morphology (Fig. 1C; upper panel), the double mutation strains had blunted hyphal tips with irregular branching (Fig. 1C; lower panel). This blunted phenotype resembled the phenotype of calcineurin deletion, indicating the likelihood of complete loss in calcineurin function due to these double mutations.

Because these mutations differentially affected hyphal growth and morphology, we next visualized the localization pattern of the respective mutated calcineurins. Mutation of single residues Phe368 (CnaA-F368A) or Asp370 (CnaA-D370A) did not impact septal localization of CnaA (Fig. 2A; upper panel). Surprisingly, while the double mutation CnaA-F368A D370A resulted only in partial or aberrant septal localization, the CnaA-F368A F372A double mutation caused complete mislocalization of CnaA from the hyphal septum (Fig. 2A; lower panel). In the CnaA-F368A D370A mutation, 65% septa showed aberrantly localized CnaA and 15% of the septa did not show any CnaA septal localization. Complete mislocalization due to the CnaA-F368A F372A mutation indicates a loss in binding of calcineurin to its substrate at the hyphal septum. Stable expression of the respective mutated proteins was confirmed by Western analysis (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, comparative sequence analysis of this region across eukaryotes indicated conservation of the FMDVF residues, revealing their importance for CnaA function (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

(A) Strains expressing FMDVF mutated CnaA-EGFP constructs cultured in GMM liquid medium on coverslips for 18–20 h. Localization is indicated as septal, partial septal or cytosolic. Arrowheads indicate proper localization of CnaA-EGFP on either side of the hyphal septa. Dotted arrow indicates aberrantly localized CnaA-EGFP at the hyphal septa following CnaA-F368A D370A mutation. White arrow indicates complete mislocalization of CnaA-EGFP from the hyphal septum upon CnaA-F368A F372A mutation. A total of 100 septa were observed in each case. Scale bar is 10 μm. (B) Western detection performed using the anti-GFP polyclonal primary antibody and peroxidase labeled anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody. Arrow indicates the ~92 kDa CnaA-EGFP fusion protein. (C) Clustal alignment of the region encompassing the FMDVF motif showing conservation between higher and lower eukaryotes. The FMDVF motif is boxed in yellow. Hs-Homo sapiens; Sc-Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Sp-Schizosaccharomyces pombe; Cn-Cryptococcus neoformans; Af-Aspergillus fumigatus; Nc-Neurospora crassa.

Previously we showed that mutation of Val371 (V371D) adjacent to Asp370 (Fig. 1A) completely abolished hyphal growth due to inhibition of interaction of CnaA with CnaB and subsequent reduction in calcineurin activity. However, the V371D mutation did not affect CnaA septal localization. Mutations in Asp370 and Phe372, along with other residues Phe378 and Val379 (residues numbered as per A. fumigatus CnaA), have also been shown to abolish CnaB-binding in the yeast and mammalian systems [26]. It remains to be determined if mutation of Phe368 also has any impact on the interaction with CnaB.

Mutations in proximity to the FMDVF motif confer FK506 resistance with no impact on CnaA septal localization

To further characterize the importance of other residues present in proximity to the FMDVF motif for septal localization and function of CnaA, we mutated the adjacent residues Asn367, Trp374 and Ser375 to Asp (N367D), Leu (W374L) and Thr (S375T), respectively. Initial growth screens did not indicate any defects compared to the akuBKU80 strain (Fig. 3A; upper panel). Moreover, septal localization of CnaA remained unaltered (data not shown), indicating that these mutations do not interfere with substrate binding and functionality of CnaA in vivo. Because the residues mutated were in the FK506-FKBP12 binding domain, we next verified the susceptibility of these strains to FK506. Interestingly, while the CnaA-W374L and CnaA-S375T strains exhibited complete resistance to FK506, the CnaA-N367D strain was only partially resistant (Fig. 3A; middle panel). The strains were also examined for susceptibility to CsA, another calcineurin inhibitor (Fig. 3A; lower panel), but none of the mutated strains displayed any CsA susceptibility differences compared to the akuBKU80 strain. To reconfirm the differential resistance observed following FK506 treatment, strains were cultured in RPMI liquid growth medium. While the CnaA-N367D strain was slightly more tolerant to FK506 than the akuBKU80 strain, the CnaA-W374L and CnaA-S375T strains did not show any growth inhibition (Fig. 3B). Together these results indicated that the Asn367, Trp374 and Ser375 residues are required for binding to the FK506-FKBP12 complex, and therefore mutations in these residues confer FK506 resistance. Because the Phe368, Asp370 and Phe372 residues are adjacent to the Asn367, Trp374 and Ser375 residues, we also verified if the FMDVF motif mutants exhibited resistance to FK506. All the FMDVF motif mutants were equally susceptible to FK506 (Fig. 1C), indicating that the mutant proteins are able to interact with the FK506-FKBP12 complex and be inhibited by FK506.

Figure 3.

(A) Mutations conferring FK506 resistance. Control strain (akuBKU80), CnaA-N367D, CnaA-W374L and CnaA-S375T strains cultured in the absence (Control; upper panel) or presence of calcineurin inhibitors FK506 (100 ng/ml; middle panel) and cyclosporine A (10 μg/ml) for 5 days. (B) 1×104 conidia of each strain inoculated into 200 μl of RPMI liquid medium in the absence or presence of FK506 (100 ng/ml), photographs (×10 magnification) taken after 24 h of growth. (C) FMDVF mutant strains examined for FK506 (100 ng/ml) susceptibility on GMM agar medium for 5 days. 1×104 conidia of each strain inoculated. Experiments were repeated three times, each in triplicate.

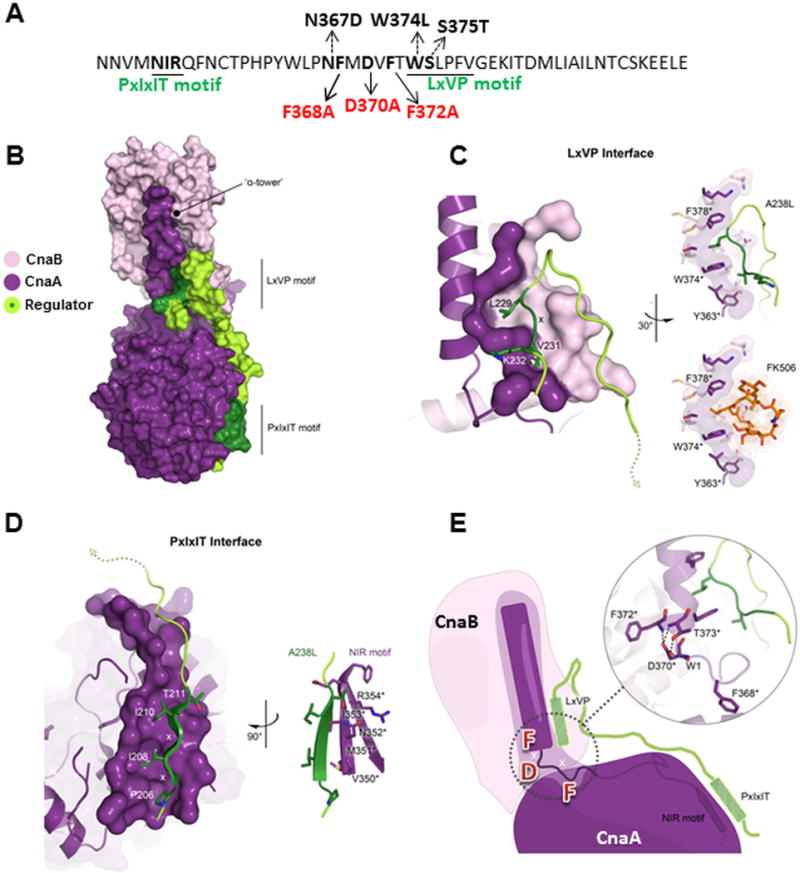

FMDVF motif forms a bridge between the PxIxIT and LxVP binding motifs

To understand the significance of the mutations and how they relate to the structure of calcineurin complexed with a substrate, we utilized the structure of human calcineurin A bound to the African swine fever virus protein A238L (PDB 4F0Z)[27] and modeled the functional motifs of A. fumigatus CnaA (Fig. 4A). Based on this model, the portion of the CnaA protruding helix, designated as the ‘α-tower’, provides the docking surface for CnaB, creating the LxVP interface for binding the substrate or the peptide regulator (Fig. 4B). The LxV portion of the regulator peptide motif interdigitates with the conserved F378 and W374 residues located on the α-tower and packs against Y363 (Fig. 4C). This is the same binding locale of FK506, explaining the competitive modality of inhibition (Fig. 4C). Although the FK506-FKBP12 binding region overlaps the LxVP substrate binding motif, we did not observe mislocalization of CnaA in the presence of FK506, raising the possibility of the FMDVF motif residues being directly involved in CnaA-substrate interaction at the septum. The PxIxIT binding interface is located on the opposite side and interacts with the NIR signature sequence (Asn352, Ile353, and Arg354) of CnaA and forms an extended β-sheet (Fig. 4D). Both the LxVP and PxIxIT substrate binding motifs interact with sites on CnaA that reside on the same linear stretch of residues, spaced only 20 amino acids apart (Fig. 4A and B). This architecture directly links the α-tower to the NIR site. Bridging these sites together is our newly identified FMDVF motif that possibly forms the foundation for orienting the α-tower (Fig. 4E). We therefore speculate that mutations in the FMDVF motif, specifically the CnaA-F368A F372A double mutation, likely disrupts the overall organization of the α-tower relative to the rest of the globular CnaA domain, which in turn affects interaction with the LxVP and PxIxIT motifs as well as localization of CnaA to the hyphal septum. This hypothetical conclusion based on our modeling should be confirmed experimentally by expressing the mutated form of CnaA and analyzing its structure in comparison to the native CnaA protein.

Figure 4.

(A) PxIxIT and LxVP substrate binding motifs with various mutations in the FMDVF motif indicated in black arrows and other mutations in the adjacent residues indicated by dotted arrows (B) Modeling functional motifs of calcineurin A from A. fumigatus and their importance for protein-substrate communication. The X-ray structure (PDB 4F0Z) of human calcineurin A (purple, CnaA) and B (pink, CnaB) bound to a viral peptide regulator (A238L; green). Both LxVP and PxIxIT binding motifs indicated and surfaces colored dark green. (C, D) Detailed interactions of the LxVP motif and calcineurin are shown. Residues with an asterisk numbered according to the A. fumigatus CnaA sequence. Molecular surfaces are of only those residues that contribute to regulator interactions and colored according to CnaA domain affiliation. The LxV portion of the regulator peptide motif interdigitates with F378* and W374* residues located on the CnaA α-tower and packs against Y363* (upper). Same binding position for FK506 is also shown from the X-ray structure (PDB 1TCO) of bovine calcineurin in complex with FK506 (lower). (D) The PxIxIT motif interacts with the NIR signature sequence of CnaA and forms an extended β-sheet. (E) Cartoon illustrates relationship between the functional motifs of substrate and CnaA domains. Bridging the LxVP and PxIxIT site is the FMDVF motif that forms the foundation for orienting the α-tower. Shown in inset figure, F368* packs into a shallow hydrophobic pocket on the surface of CnaA, whereas F372* interacts with a hydrophobic groove at the base of CnaB. D370* directly coordinates F372* and T373* orienting the N-terminal end of the α-tower.

While previous studies have reported that Thr373, Leu376 and Lys382 (residues numbered according to A. fumigatus CnaA) are also critical for FK506-FKBP12 binding [26], a recent study in Mucor circinelloides showed that mutations in CnaA residues Asn367, Trp374 and Ser375 confer FK506 resistance by altering the interactions between calcineurin and immunophilin-inhibitor complexes [28]. In this study, we have discovered a novel FMDVF motif responsible for septal localization and function of calcineurin. Based on our mutational analyses and modeling of the PxIxIT and LxVP domains we show that the FMDVF motif bridges these two domains, and it is possible that calcineurin interaction with its substrate at the hyphal septum might involve both the PxIxIT and LxVP motifs. Future identification of the protein(s) involved in tethering calcineurin to the hyphal septum would reveal the exact nature of this interaction.

Materials and Methods

Organism and culture conditions

A. fumigatus wild-type strain akuBKU80 was used and grown on glucose minimal medium (GMM) at 37 °C [29]. All growth experiments were repeated three times, each in triplicate and data presented as mean ± standard deviation. Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells were used for subcloning.

Construction of calcineurin A mutations in Aspergillus fumigatus

Site-directed mutagenesis of the FMDVF motif residues was performed using primers in Table S1 and the pUCGH-cnaA plasmid [21,22] as template. Briefly, in the first PCR, two fragments were amplified using complementary primers (with respective mutation) overlapping the cnaA region to be mutated and the respective primers at the N and C-terminus of the cnaA. No stop codon was introduced at C-terminal end of cnaA to facilitate expression of egfp fusion. Next, fusion PCR was done using equi-proportional mixture of the two PCR fragments as templates and the final cnaA mutated PCR fragment of 1674 bp was amplified with primers GCNA-F2 and GCNA-R-Bam at the N and C-terminal of cnaA (Table S1). Mutated cnaA fragments were digested with BamHI and cloned into the pUCGH-CnaApromo-CnaAterm plasmid harboring the 778 bp cnaA promoter and 386 bp cnaA terminator to facilitate homologous integration. Mutated cnaA genes were sequenced (primers in Table S2) to confirm the mutation and linearized with XbaI and HindIII for homologous integration. Linearized constructs were transformed into A. fumigatus akuBKU80 strain and transformants selected with hygromycin B (150 μg/ml) as described [1]. Transformants were verified for homologous integration by PCR and fluorescent microscopy. Recombinant strains were sequenced to confirm cnaA mutation (primers in Table S2). Site-directed mutagenesis of CnaA residues close to the FMDVF motif, Asn367 to Asp (N367D), Trp374 to Leu (W374L) and Ser375 to Thr (S375T) was performed as described for FMDVF mutations (primers in Table S1).

Protein extraction and Western analysis

A. fumigatus recombinant strains expressing respective mutated forms of CnaA-EGFP fusion protein were cultured in GMM liquid medium at 200 rpm for 24 h at 37 °C. Crude extracts were prepared as described [22]. Approximately 50 μg of protein electrophoresed on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel was transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (PVDF; Bio-Rad) and probed with rabbit polyclonal The™ anti-GFP primary antibody (1 μg/ml; GenScript) and peroxidase-labeled rabbit anti-IgG (1:5000; Rockland) secondary antibody. Detection used SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific).

Microscopy

Conidia (104) from the recombinant strains of A. fumigatus were inoculated into 5 ml GMM medium and poured over a sterile coverslip (22×60 mm; No.1) placed in a sterile dish (60×15 mm). Cultures grown for 18–20 h at 37 °C were observed by fluorescence microscopy using an Axioskop 2 plus microscope (Zeiss) equipped with AxioVision 4.6 imaging software. Each experiment was repeated three times and 100 septa were counted to assess CnaA localization.

Molecular modeling the FMDVF motif in calcineurin A

To glean direct insights into the structural role that the FMDVF motif plays with respect to the LxVP and PxIxIT motifs in protein-substrate binding and communication, the sequence of calcineurin from A. fumigatus was threaded onto the crystal structure of calcineurin complexed with the African swine fever virus protein A238L (Protein Data Bank ID: 4F0Z) using the PHYRE server. Although a homology model was generated, the sequence conservation of the functional motifs investigated in this study are identical, and surrounding regions are highly conserved. Analysis of the functional motifs was carried out using a combination of the threaded A. fumigatus homology model as well as superimposing the previously reported crystal structures of human calcineurin bound to the viral peptide regulator and bovine calcineurin in complex with the immunosuppressant inhibitor FK506 (PDB ID 4F0Z and 1TCO, respectively) using COOT. Structure and cartoon illustrations were generated using PYMOL and Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop.

Supplementary Material

Bullet Points.

Motif (FMDVF) required for proper septal localization of CnaA was identified

FK506 resistance mutations were identified in proximity to the FMDVF motif

Dual mutations in the FMDVF motif disrupt CnaA septal localization

FMDVF motif bridges the PxIxIT and LxVP substrate binding motifs

Acknowledgments

P.R.J. and W.J.S. are supported in part by NIH/NIAID grant R01 AI112595-01. YM was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81101233), and the Natural Science Foundation for youth in Shanxi province (Grant No. 2010021036-2). Modeling was performed at Duke Human Vaccine Institute Macromolecular Crystallography Shared Resource under the direction of Dr. Nathan I. Nicely. We thank Amber Richards for laboratory assistance.

Footnotes

Authors and Contribution

P.R.J. and W.J.S conceived and designed research; P.R.J., Y.M., performed research; P.R.J., and W.J.S acquired and analyzed the data; C.W.P performed molecular modeling and model data interpretation. P.R.J. and W.J.S. wrote the paper; P.R.J., Y.M., C.W.P., and W.J.S. approved the final submission.

References

- 1.Steinbach WJ, et al. Calcineurin Controls Growth, Morphology, and Pathogenicity in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryotic Cell. 2006;5:1091–1103. doi: 10.1128/EC.00139-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferreira MEdS, et al. Functional characterization of the Aspergillus fumigatus calcineurin. Fungal Genetics and Biology. 2007;44:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klee CB, Crouch TH, Krinks MH. Calcineurin: a calcium- and calmodulin-binding protein of the nervous system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1979;76:6270–6273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.12.6270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rusnak F, Mertz P. Calcineurin: Form and Function. Physiological Reviews. 2000;80:1483–1521. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu J, Farmer JD, Jr, Lane WS, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber SL. Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes. Cell. 1991;66:807–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90124-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aramburu J, García-Cózar F, Raghavan A, Okamura H, Rao A, Hogan PG. Selective Inhibition of NFAT Activation by a Peptide Spanning the Calcineurin Targeting Site of NFAT. Molecular Cell. 1998;1:627–637. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roy J, Li H, Hogan PG, Cyert MS. A Conserved Docking Site Modulates Substrate Affinity for Calcineurin, Signaling Output, and In Vivo Function. Molecular Cell. 2007;25:889–901. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martínez-Martínez S, Rodríguez A, López-Maderuelo MD, Ortega-Pérez I, Vázquez J, Redondo JM. Blockade of NFAT Activation by the Second Calcineurin Binding Site. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:6227–6235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513885200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodríguez A, et al. A Conserved Docking Surface on Calcineurin Mediates Interaction with Substrates and Immunosuppressants. Molecular Cell. 2009;33:616–626. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H, Rao A, Hogan PG. Interaction of calcineurin with substrates and targeting proteins. Trends in Cell Biology. 2011;21:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li H, Zhang L, Rao A, Harrison SC, Hogan PG. Structure of Calcineurin in Complex with PVIVIT Peptide: Portrait of a Low-affinity Signalling Interaction. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2007;369:1296–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grigoriu S, et al. The Molecular Mechanism of Substrate Engagement and Immunosuppressant Inhibition of Calcineurin. PLoS Biology. 2013;11:e1001492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S, Hou Y, Liu W, Lu C, Wang W, Sun S. Components of the Calcium-Calcineurin Signaling Pathway in Fungal Cells and Their Potential as Antifungal Targets. Eukaryotic Cell. 2015;14:324–334. doi: 10.1128/EC.00271-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinbach WJ, Reedy JL, Cramer RA, Perfect JR, Heitman J. Harnessing calcineurin as a novel anti-infective agent against invasive fungal infections. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2007;5:418–430. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cyert MS. Calcineurin signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: how yeast go crazy in response to stress. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2003;311:1143–1150. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01552-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen YL, Kozubowski L, Cardenas ME, Heitman J. On the Roles of Calcineurin in Fungal Growth and Pathogenesis. Current Fungal Infection Reports. 2010;4:244–255. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kume K, Koyano T, Kanai M, Toda T, Hirata D. Calcineurin ensures a link between the DNA replication checkpoint and microtubule-dependent polarized growth. Nature Cell Biology. 2011;13:234–242. doi: 10.1038/ncb2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugiura R, Sio SO, Shuntoh H, Kuno T. Calcineurin phosphatase in signal transduction: lessons from fission yeast. Genes to Cells. 2002;7:619–627. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu SJ, Chang YL, Chen YL. Calcineurin signaling: lessons from Candida species. FEMS Yeast Research. 2015;15 doi: 10.1093/femsyr/fov016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juvvadi PR, Lamoth F, Steinbach WJ. Calcineurin as a multifunctional regulator: Unraveling novel functions in fungal stress responses, hyphal growth, drug resistance, and pathogenesis. Fungal Biology Reviews. 2014;28:56–69. doi: 10.1016/j.fbr.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juvvadi PR, Fortwendel JR, Pinchai N, Perfect BZ, Heitman J, Steinbach WJ. Calcineurin Localizes to the Hyphal Septum in Aspergillus fumigatus: Implications for Septum Formation and Conidiophore Development. Eukaryotic Cell. 2008;7:1606–1610. doi: 10.1128/EC.00200-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juvvadi PR, Fortwendel JR, Rogg LE, Burns KA, Randell SH, Steinbach WJ. Localization and activity of the calcineurin catalytic and regulatory subunit complex at the septum is essential for hyphal elongation and proper septation in Aspergillus fumigatus. Molecular Microbiology. 2011;82:1235–1259. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juvvadi PR, et al. Phosphorylation of Calcineurin at a Novel Serine-Proline Rich Region Orchestrates Hyphal Growth and Virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Pathogens. 2013;9:e1003564. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang B, Cyert MS. Identification of a Novel Region Critical for Calcineurin Function in Vivo and in Vitro. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:18543–18551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe Y, Perrino BA, Chang BH, Soderling TR. Identification in the Calcineurin A Subunit of the Domain That Binds the Regulatory B Subunit. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:456–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawamura A, Su MSS. Interaction of FKBP12-FK506 with Calcineurin A at the B Subunit-binding Domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:15463–15466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grigoriu S, et al. The Molecular Mechanism of Substrate Engagement and Immunosuppressant Inhibition of Calcineurin. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SC, et al. Calcineurin orchestrates dimorphic transitions, antifungal drug responses and host–pathogen interactions of the pathogenic mucoralean fungus Mucor circinelloides. Molecular Microbiology. 2015;97:844–865. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimizu K, Keller NP. Genetic Involvement of a cAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase in a G Protein Signaling Pathway Regulating Morphological and Chemical Transitions in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics. 2001;157:591–600. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.2.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.