Abstract

Background

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is associated with poor survival. This study compares the outcome of patients with unresectable ICC treated with hepatic arterial infusion (HAI) plus systemic chemotherapy (SYS) to SYS alone.

Methods

Consecutive patients with ICC were retrospectively reviewed. Clinicopathologic data were reviewed. Survival rates were compared by Kaplan-Meier analysis and log rank test.

Results

Between 1/2000 and 8/2012, 525 patients with ICC were evaluated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and 236 patients with unresectable tumors (locally advanced or metastatic) were analyzed. Disease was confined to the liver in 104 patients who underwent treatment with combined HAI and SYS (78, 75%) or SYS alone (26, 25%). The response rate in the combined group was better than in those who received SYS alone, although this did not reach statistical significance (59% vs 39%, respectively; p=0.11). Overall survival in the combined group was longer compared to patients who received SYS alone (30.8 months vs 18.4 months, respectively; p<0.001), and this difference was maintained when patients with portal lymph node disease were included in the survival analysis (HAI and SYS n=93 with survival 29.6 months vs SYS n=74 with survival 15.9 months, respectively; p<0.001). Eight patients who initially presented with unresectable tumors responded enough to undergo complete resection and had a median overall survival of 37 months (range=10.4 – 92.3 months).

Conclusion

In patients with unresectable ICC confined to the liver or with limited regional nodal disease, combined SYS and HAI chemotherapy is associated with greater survival compared to SYS alone.

Keywords: Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, hepatic arterial infusion, FUDR, systemic chemotherapy, survival

Introduction

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is the second most common primary liver cancer and is increasing in incidence(1). Unresectable ICC is associated with a median survival of less than 5 months without treatment(2), and about 1 year with contemporary systemic chemotherapy(3). Patients who undergo resection with curative intent frequently develop a recurrence,(4) resulting in a median survival ranging from 27 to 36 months(4, 5). The ABC-02 phase 3 trial established the current standard of systemic chemotherapy (SYS) in advanced biliary cancer but showed only a modest survival benefit in patients treated with gemcitabine-cisplatin compared to gemcitabine monotherapy (11.7 months vs 8.1 months, respectively)(3). More effective non-operative therapies are therefore necessary if improvements in outcome are to be realized.

Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAI) represents a locoregional approach that administers a continuous infusion of drug directly into the liver, thereby allowing much greater drug delivery to the tumor without increasing systemic toxicity(6). Other hepatic artery based treatment modalities that are being utilized for unresectable ICC include transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and radioembolization with Yttrium-90(7, 8).

The greatest experience with HAI has been in patients with colorectal liver metastases, particularly those with advanced disease. Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of HAI in both the adjuvant and unresectable disease settings, with significantly higher response rates, less toxicity and, in some cases, a potential survival benefit compared to systemic chemotherapy alone (9–17). By contrast, experience with HAI in primary liver cancer is much more limited. Studies in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma have suggested efficacy and a potential survival benefit for patients who respond to a combination of systemic chemotherapy and HAI(18, 19). The existing experience on ICC has been limited to small phase I and II trials using a variety of agents with promising results(20–22). The authors have previously published their experience with HAI FUDR monotherapy and FUDR in combination with bevacizumab in unresectable primary liver cancer in two phase II clinical trials with encouraging response rates and median survival of approximately 30 months(23, 24); however, large, prospective trials comparing HAI with SYS to SYS alone have not been performed.

The aims of the present study were to compare the response and survival after SYS with combined HAI and SYS in patients with unresectable ICC. The study represents a retrospective review of a consecutive series of patients with unresectable ICC treated with systemic chemotherapy (SYS), with or without HAI, over a 12-year period.

Patients and Methods

Patients and Tumors

This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board and is HIPAA compliant. Prospectively maintained databases in the Department of Surgery were queried to identify patients with ICC referred for surgical evaluation; an institutional database was also queried for patients with the ICD-9 diagnosis code 155.1 (malignant neoplasm of intrahepatic bile ducts) to identify all ICC patients referred for non-surgical therapy. The study included only patients with a histologically confirmed diagnosis of ICC that was not amenable to resection at initial presentation, as determined by attending hepatobiliary surgeons. Unresectable disease included distant metastases, non-reconstructable vascular involvement, or severe underlying liver parenchymal disease. Patients with multifocal tumors and extensive regional nodal disease were, in general, considered unresectable, due to the poor prognosis associated with these findings. Satellite lesions were defined as ICC nodules separate from the main tumor mass. Patients submitted to resection and those not treated with chemotherapy or treated elsewhere or with missing treatment and/or outcome data were excluded from this study.

The majority of patients initially considered candidates for resection or HAI pump placement underwent surgical exploration, and their staging was derived from the operative findings. Patients who were not explored were staged based on imaging. Evidence of extra-hepatic disease in the initial imaging (nodal disease, distant metastases) was reviewed on subsequent scans for the purpose of this study, and evidence of radiologic progression was used to confirm the presence of disease.

Patients with unresectable disease were referred for treatment with chemotherapy, either SYS alone, or combined SYS and HAI, based on disease extent and at the discretion of the treating medical oncologist. The indications for HAI chemotherapy in patients with ICC and the technique of HAI pump placement have been published previously(23, 24). Briefly, patients were considered for HAI placement if they had liver confined disease with <70% of the liver involved. Exclusion criteria included prior hepatic radiation or treatment with FUDR, Karnofsky performance status <60, first-degree sclerosing cholangitis, Gilbert’s disease, portal hypertension, severe hepatic parenchymal dysfunction (encephalopathy, serum albumin <2.5 g/dl, serum bilirubin ≥1.8 mg/dl, or international normalized ration (INR) >1.5), portal inflow occlusion, WBC <3500 cells/mm3, concurrent malignancy (except localized basal or squamous cell skin cancers), active infection, and concurrent pregnancy or lactation (females). Forty-four patients who received HAI were part of two previously reported clinical trials(23, 24). The first trial reported on thirty-four unresectable patients with primary liver cancer (26 ICC) and investigated the use of dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) for assessment of the tumor vascularity as a biomarker of outcome. The second trial reported on 22 unresectable patients with primary liver cancer (18 ICC) and investigated the safety and efficacy of adding systemic (IV) bevacizumab to HAI. HAI therapy was typically reserved for patients with disease confined to the liver or selected patients with limited regional lymph node disease (ie, porta hepatis), often identified at the time of exploration. Systemic chemotherapy without HAI was the treatment of choice for all patients with lymph node disease beyond the porta hepatis (ie, celiac, para-aortic).

HAI chemotherapy consisted of a continuous infusion of floxuridine (FUDR) into the hepatic arterial circulation, administered through the surgically implanted pump, with a predetermined flow rate (23). Pump chemotherapy treatment generally began 2 weeks after pump placement, with each cycle consisting of 2 weeks of continuous FUDR infusion followed by 2 weeks of heparin-saline; concurrent systemic chemotherapy was typically delivered during this latter 2-week period. In the face of disease progression in the liver, selected patients received side port injections of mitomycin C or gemcitabine. The administration of HAI and SYS chemotherapy has been described in several prior publications (23–25). A variety of systemic regimens were used in combination with HAI. For patients treated with SYS alone, gemcitabine-based combination therapy was used most often, although several different agents were ultimately employed.

After the onset of treatment, patients were followed at approximately 3-month intervals with computerized tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans and positron emission tomography (PET) scans were obtained during treatment to investigate specific findings, as necessary. Response to therapy was assessed with the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST 1.1)(26). When disease progression was evident, the treatment regimen was changed or new agents were added, depending on the specific findings(23, 24). Liver disease progression for a patient on HAI led to adding either a systemic chemotherapy agent and/or another HAI agent via sideport injection. Extrahepatic progression was treated with adding or modifying the systemic chemotherapy regimen according to disease response.

Treatment with SYS and/or HAI continued until one of the following conditions was observed: liver disease progression, extrahepatic progression, treatment-related toxicity/complications, or until surgical resection. Toxicity during chemotherapy was graded according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Toxicity Criteria 3.0. With regard to biliary toxicity, liver function tests are routinely evaluated during each HAI cycle. Dose modifications of FUDR were calculated according to the changes in liver function tests. Hepatic toxicity from treatment was defined as a significant increase over individual pre-treatment values (two-fold or greater for alkaline phosphatase, three-fold or greater for AST, and 1.5-fold or greater for bilirubin), leading to dose reduction, as described previously(27). Our experience with biliary toxicity related to HAI in combination with bevacizumab has been reported previously (24, 28).

Outcomes Measures and Statistical Analysis

Responses based on RECIST and overall survival were analyzed in patients stratified by treatment (HAI and SYS vs SYS alone) and disease extent (liver-only with or without regional nodal disease); patients with distant metastatic disease were included in the survival analysis for comparison purposes. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 14.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney test were used to compare continuous variables, and χ2 test and Fischer’s exact test were used to compare categorical variables as appropriate. Overall Survival (OS) was measured from the date of the first histological diagnosis until death or last follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) was measured from the date of treatment initiation until first documented progression, death, or last follow-up. Survival rates were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The log rank test was used to assess differences between survival curves. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Clinicopathologic Characteristics

Between January 2000 and August 2012, 525 patients with biopsy confirmed ICC were evaluated at MSKCC. After excluding patients who underwent resection (n=138) and those who received treatment elsewhere without sufficient data (n=151), 236 patients with unresectable ICC had complete clinicopathologic, chemotherapy and survival data available. Of these, 167 patients had disease confined to the liver and/or regional lymph nodes and represent the focus of this study; the remaining 69 patients had distant metastases.

The characteristics of the 167 patients without distant disease are summarized in Table 1. Median age of all patients was 62 years (range: 30–88) and the majority (59%) were female. The most frequent presentation was abdominal pain (43%). Median radiologic tumor size was 8.5 cm (range: 1.5–16.4 cm); most tumors involved both liver lobes (74%), were multifocal (63.5%) and were moderately differentiated (67%). The majority of included patients (n=117 (70%)) had unresectable disease at exploration, of which 93 (56%) underwent HAI pump placement. Overall, 104 patients (62%) had disease confined to the liver (i.e. without nodal disease), but were not candidates for resection due to locally advanced and/or multifocal tumors, whereas 63 (38%) were found to have nodal disease.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 167 patients with unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) and no distant metastases

| Characteristic | N=167(%) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Median Age (range, yr) | 62(30–88) |

| Female Gender | 99(59) |

| Presenting Symptom | 165 |

| Abdominal Pain | 72(43) |

| Jaundice | 17(10) |

| Elevated LFTs | 26(16) |

| Non-specific GI symptoms (nausea, weight loss) | 17(10) |

| Incidentally found during imaging | 23(14) |

| Non-GI complains (chest pain, back pain, fever) | 10(6) |

| Radiology | |

| Median Tumor Size (range) | 8.5(1.5–16.4) |

| Bilobar disease | 123(74) |

| Multifocal | 106(63.5) |

| Surgical Exploration | 117(70) |

| Unresectability Reason | |

| Locally advanced/multifocal tumors | 104(44) |

| Nodal disease | 63(27) |

| Histologic Grade (n) | 126 |

| Well | 1(1) |

| Moderately | 84(67) |

| Poor | 41(32) |

| Treatment | |

| SYS | 74(44) |

| HAI plus SYS | 93(56) |

| Surgery with curative intent after treatment | 9(5) |

HAI: Hepatic Arterial Infusion, SYS: systemic chemotherapy

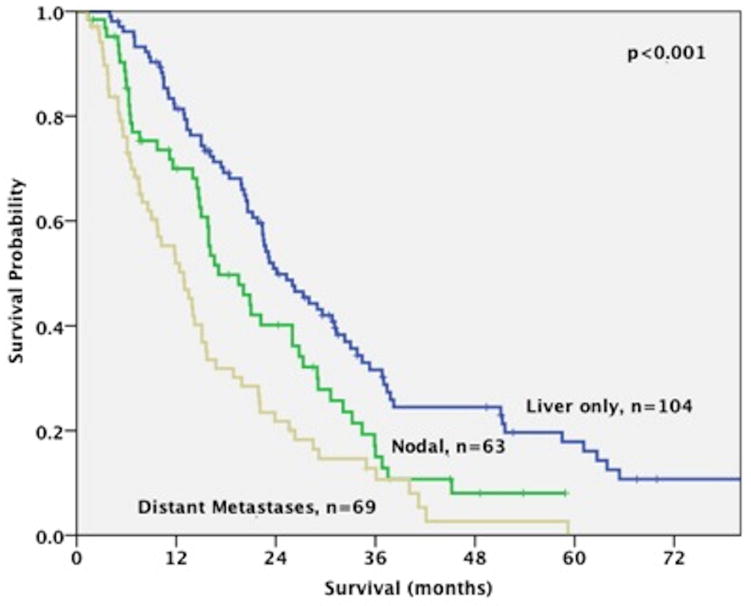

At the time of analysis, the majority of the 236 patients (79%) were dead of disease. The median OS for the study cohort was 20.1 months (range: 1.3–120.3 months). Patients with liver-only disease experienced a better survival compared to patients with nodal disease or distant metastases, irrespective of treatment (24.1 months (range: 4–120.3 months) vs 17.1 months (range: 1.4–58.9 months) vs 12.4 months (range: 1.3–59.2 months), respectively; p<0.001) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overall Median Survival for 236 patients with advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) according to disease location (liver-only disease: 24.1 months, nodal disease: 17.1 months, distant metastases: 12.9 months; p<0.001).

Hepatic Arterial Infusion and Systemic Chemotherapy. Treatment Groups and Chemotherapy Agents

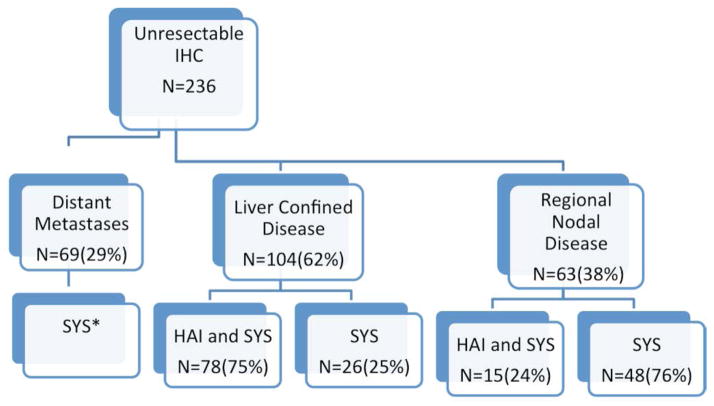

Figure 2 shows a schema of all patients according to disease extent and the treatment received. The majority of patients with liver confined disease (75%) received both SYS and HAI; 6 patients (2.5%) received only HAI, as they did not tolerate SYS but are included in the HAI and SYS group. By contrast, patients with regional nodal disease were most frequently (76%) treated with SYS alone.

Figure 2.

Schema of 236 patients with unresectable ICC who were treated with systemic chemotherapy (SYS) and/or hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAI)

*nine patients received also HAI (had equivocal evidence of distant metastases at time of HAI placement which progressed/mainly lung nodules)

**six patients received only HAI (systemic chemotherapy was not tolerated)

Table 2 outlines the administered chemotherapy agents for the 167 patients with disease confined to the liver and/or regional lymph nodes who are the focus of this study. In total, 93 patients received HAI (56%). FUDR was used in all of these patients, with mitomycin C added in 38%; gemcitabine-based HAI was used in 3%. The most common systemic chemotherapy agents used in combination with HAI was a gemcitabine-based regimen (86%); irinotecan-and 5-fluoruracil-based regimens were used in 67% and 54% of patients, respectively. Forty-four patients were treated in the setting of two clinical trials (26 with FUDR monotherapy and 18 with FUDR plus bevacizumab).

Table 2.

Chemotherapy Lines and Agents

| N=167(%) | |

|---|---|

| Systemic Chemotherapy and | 93(56) |

| HAI | |

| HAI Agents | |

| FUDR monotherapy | 93(100) |

| FUDR/Mitomycin | 35(38) |

| Gemcitabine | 3(3) |

| Systemic Agents | |

| Gemcitabine regimen | 80(86) |

| Irinotecan regimen | 62(67) |

| 5-Fluoruracil regimen | 50(54) |

| Systemic Chemotherapy Only | 74(44) |

| First Line Regimen | |

| Gemcitabine-based | 58(78) |

| Gemcitabine Monotherapy | 18(24) |

| Gemcitabine with second agent* | 40(76) |

| Other Agents* | 16(22) |

| Second Line Regimen | 34(46) |

| 5-Fluoruracil-based | 22(65) |

| Third Line Regimen | 7(9) |

A variety of systemic chemotherapy regimens were used: gemcitabine monotherapy, gemcitabine/cisplatin, gemcitabine/cisplatin/sorafenib, gemcitabine/cisplatin/irinotecan, gemcitabine/oxaliplatin, gemcitabine/capecitabine, gemcitabine/erlotinib, gemcitabine/irinotecan, gemcitabine/carboplatin/taxol, 5-fluoruracil, 5-fluoruracil/irinotecan, 5-fluoruracil/oxaliplatin, other systemic agents (GX-8951S, platinum based regimens, taxol based regimens)

In patients who received only SYS therapy, 78% were administered gemcitabine-based regimens as first line and 65% were administered 5-fluoruracil regimens as second line. Of patients who received only SYS therapy, 85% received gemcitabine-based chemotherapy at some point in their treatment, the vast majority of which were either gemcitabine/cisplatin (30%), or another gemcitabine-based multiagent therapy (43%) such as gemcitabine/oxaliplatin.

Patients with Liver Confined Disease. HAI and SYS versus SYS Alone

Among the 104 patients with liver confined disease, the majority n=78(75%) were treated with HAI and SYS versus 26(25%) SYS alone. Table 3 shows the clinicopathologic characteristics of these patients. All patients who were treated with HAI underwent surgical exploration, whereas 11(42%) of the patients treated with SYS alone were also surgically explored.

Table 3.

Patients with liver confined disease (n=104) (%)

| Characteristic | SYS (n=26) | SYS and HAI (n=78) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Median Age (range, yr) | 56(41–88) | 62(30–84) | 0.82 |

| Female Gender | 13(50) | 47(60) | 0.37 |

| Presenting Symptom | 0.38 | ||

| Abdominal Pain | 12(46) | 30(38) | |

| Jaundice | 5(19) | 5(6) | |

| Elevated LFTs | 2(8) | 14(18) | |

| Non-specific GI symptoms | 3(11) | 10(13) | |

| Incidentally found during imaging | 3(11) | 13(17) | |

| Non-GI complains | 1(4) | 4(5) | |

| Radiology | |||

| Median Tumor Size (range) | 6.8(2.7–15.5) | 9.4(2.1–14.6) | 0.14 |

| Satellite Lesions | 21(81) | 51(65) | 0.22 |

| Bilobar disease | 19(73) | 61(87) | 0.6 |

| Histologic Grade (n) | 19 | 59 | 0.75 |

| Well | 0 | 1(2) | |

| Moderately | 13(68) | 43(73) | |

| Poor | 6(32) | 15(25) | |

| Surgery with Curative Intent after Induction Chemotherapy | 2(8) | 3(4) | 0.6 |

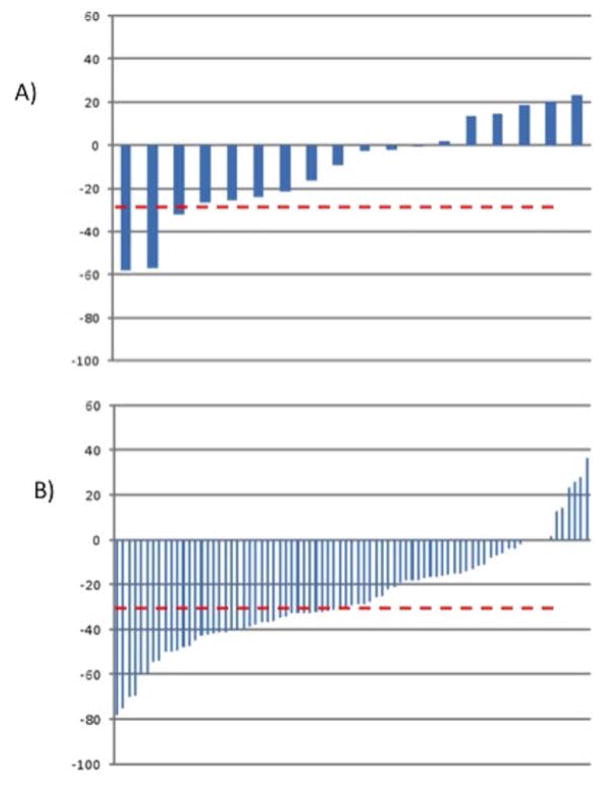

Overall, patients who received only SYS had patient and tumor characteristics similar to patients treated with HAI and SYS. Based on available chemotherapy response data, (HAI: 78 and SYS: 18), the response rate for patients who received HAI and SYS was better than for those who received SYS alone. A partial response according to RECIST was observed in 47 of 79 (59%) after HAI and SYS, versus 7 of 18 (39%) for patients with SYS (p=0.11) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Waterfall plots presenting the ranking of individual patients according to RECIST response to treatment. A) response with systemic chemotherapy (n=7 of 18 patients or 39%), B) response with HAI chemotherapy (n=47 of 79 or 59%) (p=0.11)

(y axis: % change in tumor diameter, red line 30% response)

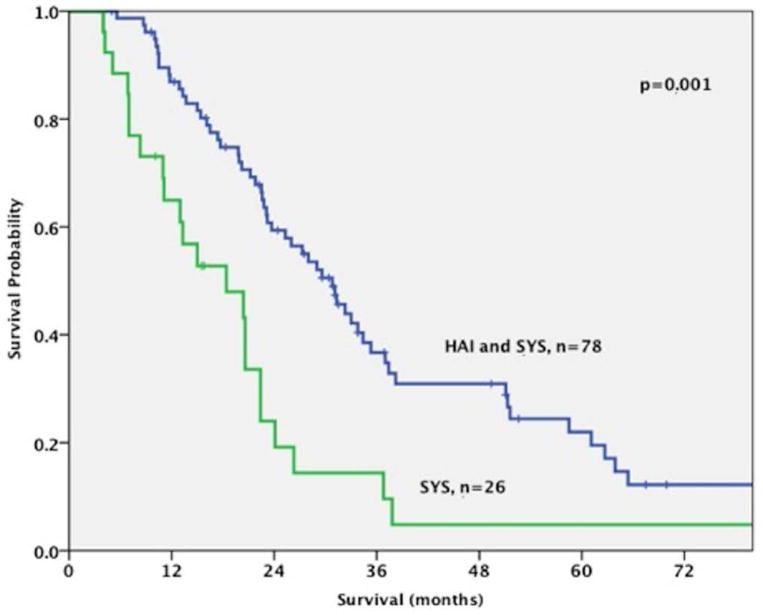

Progression-free survival was better for the HAI and SYS group, although this did not reach statistical significance (12 months vs 7 months, p=0.2). The combination of both HAI and SYS was associated with an improved overall survival compared to patients who received only SYS (30.8 months vs 18.4 months, respectively; p<0.001) (figure 4). When patients who received both HAI and SYS (n=78) were compared to those treated with SYS only and specifically received either gemcitabine/cisplatin or gemcitabine/oxaliplatin (n=9), the survival difference was maintained (30.8 months vs 15 months, respectively; p<0.001). When patients with regional nodal disease were included in the survival analysis, the advantage of HAI and SYS over SYS alone was maintained (29.6 months (range 3.4–120.3 months) vs 15.9 months (range: 1.4–45.2 months), respectively; p<0.001).

Figure 4.

Patients with liver-only disease who underwent treatment with Hepatic Arterial Infusion (HAI) and Systemic (SYS) Chemotherapy (N=78) had an improved survival compared to those who were treated only with Systemic Chemotherapy (N=26) (30.8 months vs 18.4 months, respectively; p<0.001)

Patients Submitted to Resection after Conversion Chemotherapy

In total, 8 patients who initially presented with unresectable tumors underwent a resection with curative intent after conversion chemotherapy. Four patients received SYS only and four SYS and HAI (one patient in the latter group received HAI only). Median age of these patients was 63.5 years (range: 41–80) and 4 were female. Five of these patients (62%) were initially not candidates for resection due to liver-confined advanced disease and three due to nodal disease. Median time from initial diagnosis to resection was 11 months (range=7–36 months) and from chemotherapy initiation to resection 10 months (range=5.3–33.9 months). Seven of 8 resections were extended hepatectomies and resection margins were negative in 5 patients; median tumor size was 6 cm (range: 4–9.5 cm) and 2 patients had confirmed metastatic disease to regional lymph nodes. Two patients died peri-operatively, and five patients recurred within a year. The two patients with nodal disease received only systemic chemotherapy. Two patients remain with no evidence of disease after more than 5 years from the initial diagnosis (one had a small recurrence which was ablated percutaneously). The median overall survival since surgery for all patients who underwent resection was 36.9 months (range: 10.4–92.3 months).

Discussion

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, albeit the second most common primary liver cancer, is a rare malignancy. It has been increasing in frequency and mortality(29) likely due to increase in established risk factors, such as HCV and nonalcoholic liver disease, as well as due to more accurate recognition(30, 31). Most of these tumors present in an advanced unresectable stage with limited treatment options, whereas even resectable disease frequently recurs and is associated with a limited survival(4, 5). More effective treatments are thus needed.

Currently, the gold standard for advanced biliary tumors consists of a combination of gemcitabine plus cisplatin, which offers a modest survival over gemcitabine monotherapy (11.7 vs 8.1 months, respectively)(3). Other gemcitabine-based regimens, notably gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin, have shown similar efficacy(32). The large majority of SYS patients with disease confined to the liver and regional lymph nodes in this study were treated with gemcitabine (85%), which was combination therapy in 73%. The addition of biologic agents such as cetuximab has failed so far to lead to improvement in survival of these patients (33). Recent advancements in knowledge of the biology of these tumors and identification of novel mutations are expected to aid in the identification of new, targeted therapies that could potentially lead to improvements in survival(34, 35).

Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy represents a therapeutic approach that combines delivery of high doses of chemotherapy directly to the arterial circulation where tumors derive most of their supply, minimizing the systemic toxicity of the chemotherapeutic agent. FUDR, a pyrimidine antimetabolite transformed to 5-FU in the liver, is the preferred agent in our institution as it has an extraction rate of 94% to 99% in the liver during the first pass, leading to a high ratio of hepatic-to-systemic drug exposure and minimizing the systemic toxicity (36). The use of HAI for the treatment of extensive colorectal cancer liver metastases is associated with improved responses, less toxicity, and a potential survival benefit compared to systemic chemotherapy alone. The use of HAI in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is limited to small clinical trials frequently combining HAI with a variety of systemic agents(20–23). We had previously reported two clinical trials on the use of FUDR first alone and subsequently combined with systemic bevacizumab for unresectable primary liver cancer, the majority of the patients with cholangiocarcinomas(23, 24). The first trial demonstrated the safety and efficacy of HAI for ICC (23). The second trial concluded that the addition of bevacizumab to HAI with FUDR increased the biliary toxicity without an improved outcome(24). In these trials, we reported high response rates and a median survival of approximately 30 months.

In the present study, we report our entire experience with HAI and SYS in a large series of patients with unresectable ICC. Patients with liver confined disease who were treated with both HAI and SYS experienced better response rates and improved survival compared to patients who received only SYS (30.8 months vs 18.4 months, respectively), a survival benefit that was maintained when patients with nodal disease were included in the survival analysis (29.6 months vs 15.9 months, respectively). The combination of HAI and SYS aims to maximize the therapeutic effect in the liver, while also treating microscopic metastatic disease at extrahepatic sites.

Only eight patients eventually underwent a resection with curative intent after induction treatment with SYS and/or HAI, with a median survival time of 3 years. This conversion to resectability rate is far below the rates achieved for colorectal cancer liver metastases (34, 35). Whether the combination of HAI and systemic chemotherapy can lead to improved resectability rates for this disease that usually presents in advanced, unresectable stage merits more investigation.

The main limitations of this study are its retrospective nature and the single institutional experience. The former has obvious implications for potential bias introduced into patient selection, while the latter precludes generalizability of the recommendations, pending confirmation in a multicenter study. Given that a significant proportion of the HAI patients (n=44) were derived from two clinical trials, the generalizability of the results will be somewhat limited, and while inclusion of patients with regional nodal disease helps in this regard, confirmation of the results in larger studies will be required. The heterogeneity of systemic chemotherapy regimens, which is inherent to studies other than controlled clinical trials, represents a limitation and must be considered when interpreting these results. Additionally, potential differences in staging might have existed between the groups, given that not all patients were staged surgically; however, to minimize this possibility, equivocal radiologic findings were followed in serial scans to determine their nature. Despite these limitations, however, the results of the present study represent the best reported treatment results in patients with advanced ICC and demand that the HAI and SYS treatment approach be further investigated.

Future studies should investigate the best systemic regimen combined with regional FUDR. Additionally, recent studies of ICC have suggested a number of potentially exploitable mutations in known cancer-related genes; continued efforts to characterize these mutations may not only help identify patients most likely to benefit from this treatment approach, but may also open up other therapeutic avenues.

In conclusion, in this retrospective review, the use of HAI chemotherapy offered a partial response in 59% of patients and was associated with a higher overall survival when compared to the use of systemic chemotherapy alone for unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma confined to the liver and/or the portal nodes (30.8 months vs 18.4 months). The efficacy of regional FUDR is established. Whether the survival benefit observed in our study is derived from the use of FUDR will need to be answered in larger prospective studies.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748

Footnotes

No conflict of interest disclosures from any authors

References

- 1.Shaib YH, Davila JA, McGlynn K, El-Serag HB. Rising incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a true increase? Journal of hepatology. 2004 Mar;40(3):472–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park J, Kim MH, Kim KP, Park do H, Moon SH, Song TJ, et al. Natural History and Prognostic Factors of Advanced Cholangiocarcinoma without Surgery, Chemotherapy, or Radiotherapy: A Large-Scale Observational Study. Gut and liver. 2009 Dec;3(4):298–305. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2009.3.4.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2010 Apr 8;362(14):1273–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Endo I, Gonen M, Yopp AC, Dalal KM, Zhou Q, Klimstra D, et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: rising frequency, improved survival, and determinants of outcome after resection. Annals of surgery. 2008 Jul;248(1):84–96. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318176c4d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Jong MC, Nathan H, Sotiropoulos GC, Paul A, Alexandrescu S, Marques H, et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: an international multi-institutional analysis of prognostic factors and lymph node assessment. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011 Aug 10;29(23):3140–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sullivan RD, Norcross JW, Watkins E., Jr Chemotherapy of Metastatic Liver Cancer by Prolonged Hepatic-Artery Infusion. The New England journal of medicine. 1964 Feb 13;270:321–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196402132700701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown DB, Geschwind JF, Soulen MC, Millward SF, Sacks D. Society of Interventional Radiology position statement on chemoembolization of hepatic malignancies. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR. 2006 Feb;17(2 Pt 1):217–23. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000196277.76812.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ibrahim SM, Mulcahy MF, Lewandowski RJ, Sato KT, Ryu RK, Masterson EJ, et al. Treatment of unresectable cholangiocarcinoma using yttrium-90 microspheres: results from a pilot study. Cancer. 2008 Oct 15;113(8):2119–28. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiorentini G, Cantore M, Rossi S, Vaira M, Tumolo S, Dentico P, et al. Hepatic arterial chemotherapy in combination with systemic chemotherapy compared with hepatic arterial chemotherapy alone for liver metastases from colorectal cancer: results of a multi-centric randomized study. In vivo. 2006 Nov-Dec;20(6A):707–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goere D, Deshaies I, de Baere T, Boige V, Malka D, Dumont F, et al. Prolonged survival of initially unresectable hepatic colorectal cancer patients treated with hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin followed by radical surgery of metastases. Annals of surgery. 2010 Apr;251(4):686–91. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d35983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.House MG, Kemeny NE, Gonen M, Fong Y, Allen PJ, Paty PB, et al. Comparison of adjuvant systemic chemotherapy with or without hepatic arterial infusional chemotherapy after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer. Annals of surgery. 2011 Dec;254(6):851–6. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822f4f88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ducreux M, Ychou M, Laplanche A, Gamelin E, Lasser P, Husseini F, et al. Hepatic arterial oxaliplatin infusion plus intravenous chemotherapy in colorectal cancer with inoperable hepatic metastases: a trial of the gastrointestinal group of the Federation Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005 Aug 1;23(22):4881–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kemeny NE, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis DR, Lenz HJ, Warren RS, Naughton MJ, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion versus systemic therapy for hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: a randomized trial of efficacy, quality of life, and molecular markers (CALGB 9481) Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006 Mar 20;24(9):1395–403. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.8166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerr DJ, McArdle CS, Ledermann J, Taylor I, Sherlock DJ, Schlag PM, et al. Intrahepatic arterial versus intravenous fluorouracil and folinic acid for colorectal cancer liver metastases: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2003 Feb 1;361(9355):368–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12388-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mocellin S, Pilati P, Lise M, Nitti D. Meta-analysis of hepatic arterial infusion for unresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer: the end of an era Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007 Dec 10;25(35):5649–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mancini R, Tedesco M, Garufi C, Filippini A, Arcieri S, Caterino M, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion (HAI) of cisplatin and systemic fluorouracil in the treatment of unresectable colorectal liver metastases. Anticancer research. 2003 Mar-Apr;23(2C):1837–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kemeny N, Jarnagin W, Paty P, Gonen M, Schwartz L, Morse M, et al. Phase I trial of systemic oxaliplatin combination chemotherapy with hepatic arterial infusion in patients with unresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005 Aug 1;23(22):4888–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamashita T, Arai K, Sunagozaka H, Ueda T, Terashima T, Yamashita T, et al. Randomized, phase II study comparing interferon combined with hepatic arterial infusion of fluorouracil plus cisplatin and fluorouracil alone in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2011;81(5–6):281–90. doi: 10.1159/000334439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ueshima K, Kudo M, Takita M, Nagai T, Tatsumi C, Ueda T, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy using low-dose 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2010 Jul;78( Suppl 1):148–53. doi: 10.1159/000315244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cantore M, Mambrini A, Fiorentini G, Rabbi C, Zamagni D, Caudana R, et al. Phase II study of hepatic intraarterial epirubicin and cisplatin, with systemic 5-fluorouracil in patients with unresectable biliary tract tumors. Cancer. 2005 Apr 1;103(7):1402–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mambrini A, Guglielmi A, Pacetti P, Iacono C, Torri T, Auci A, et al. Capecitabine plus hepatic intra-arterial epirubicin and cisplatin in unresectable biliary cancer: a phase II study. Anticancer research. 2007 Jul-Aug;27(4C):3009–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inaba Y, Arai Y, Yamaura H, Sato Y, Najima M, Aramaki T, et al. Phase I/II study of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with gemcitabine in patients with unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (JIVROSG-0301) American journal of clinical oncology. 2011 Feb;34(1):58–62. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181d2709a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarnagin WR, Schwartz LH, Gultekin DH, Gonen M, Haviland D, Shia J, et al. Regional chemotherapy for unresectable primary liver cancer: results of a phase II clinical trial and assessment of DCE-MRI as a biomarker of survival. Ann Oncol. 2009 Sep;20(9):1589–95. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kemeny NE, Schwartz L, Gonen M, Yopp A, Gultekin D, D’Angelica MI, et al. Treating primary liver cancer with hepatic arterial infusion of floxuridine and dexamethasone: does the addition of systemic bevacizumab improve results? Oncology. 2011;80(3–4):153–9. doi: 10.1159/000324704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen PJ, Nissan A, Picon AI, Kemeny N, Dudrick P, Ben-Porat L, et al. Technical complications and durability of hepatic artery infusion pumps for unresectable colorectal liver metastases: an institutional experience of 544 consecutive cases. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2005 Jul;201(1):57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.03.019. Epub 2005/06/28. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) European journal of cancer. 2009 Jan;45(2):228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kemeny N, Capanu M, D’Angelica M, Jarnagin W, Haviland D, Dematteo R, et al. Phase I trial of adjuvant hepatic arterial infusion (HAI) with floxuridine (FUDR) and dexamethasone plus systemic oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin in patients with resected liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2009 Jul;20(7):1236–41. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kemeny NE, Jarnagin WR, Capanu M, Fong Y, Gewirtz AN, Dematteo RP, et al. Randomized phase II trial of adjuvant hepatic arterial infusion and systemic chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with resected hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011 Mar 1;29(7):884–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.5977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2001 Jun;33(6):1353–7. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bridgewater J, Galle PR, Khan SA, Llovet JM, Park JW, Patel T, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Journal of hepatology. 2014 Jun;60(6):1268–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Welzel TM, Graubard BI, El-Serag HB, Shaib YH, Hsing AW, Davila JA, et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a population-based case-control study. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2007 Oct;5(10):1221–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andre T, Tournigand C, Rosmorduc O, Provent S, Maindrault-Goebel F, Avenin D, et al. Gemcitabine combined with oxaliplatin (GEMOX) in advanced biliary tract adenocarcinoma: a GERCOR study. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2004 Sep;15(9):1339–43. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malka D, Cervera P, Foulon S, Trarbach T, de la Fouchardiere C, Boucher E, et al. Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin with or without cetuximab in advanced biliary-tract cancer (BINGO): a randomised, open-label, non-comparative phase 2 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2014 Jul;15(8):819–28. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70212-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hezel AF, Deshpande V, Zhu AX. Genetics of biliary tract cancers and emerging targeted therapies. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010 Jul 20;28(21):3531–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiao Y, Pawlik TM, Anders RA, Selaru FM, Streppel MM, Lucas DJ, et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent inactivating mutations in BAP1, ARID1A and PBRM1 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. Nature genetics. 2013 Dec;45(12):1470–3. doi: 10.1038/ng.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collins JM. Pharmacologic rationale for regional drug delivery. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1984 May;2(5):498–504. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.5.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]