Abstract

Background

Limited data are available on long-term morbidity in adult retinoblastoma (Rb) survivors.

Methods

The Rb Survivor Study is a retrospective cohort of adult Rb survivors diagnosed between 1932 and 1994. Participants completed a comprehensive questionnaire, adapted from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) surveys. Chronic conditions were classified using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.03. Multivariate Poisson regression was used to compare Rb survivors with 2,377 non-Rb controls, consisting of the CCSS sibling cohort, and survivors with bilateral versus unilateral disease.

Results

Rb survivors (53.6% with bilateral disease) and non-Rb controls had mean ages of 43.3 (SD 11) and 37.6 (SD 8.6) years, respectively, at study enrollment. At a median follow-up of 42 years (range, 15-75), 86.6% of Rb survivors had at least one condition and 71.1% had a severe/life-threatening (grade 3-4) condition. The adjusted relative risk of a chronic condition in survivors, compared to non-Rb controls, was 1.4 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.3–1.4, p<0.01); for a grade 3-4 condition, the risk was 7.6 (95% CI, 6.4–8.9, p<0.01). Survivors were at excess risk regardless of laterality. After stratifying by laterality and excluding ocular conditions and SMN, only those with bilateral disease were at increased risk for any non-ocular, non-SMN condition (RR 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1–1.2) and for grade 3-4 non-ocular, non-SMN conditions (RR 1.7; 95% CI, 1.2–2.5).

Conclusions

Rb survivors have an increased risk of chronic conditions compared to non-Rb controls. After excluding ocular conditions and SMN, this excess risk persists only for those with bilateral disease.

Keywords: survivors, retinoblastoma, risk, follow-up studies, questionnaires

Introduction

Retinoblastoma (Rb) is the most common intraocular tumor of childhood. Due to therapeutic advances, survival rates in higher-income countries now exceed 95% 1. While much is known about Rb survivors' oculo-visual problems, as well as the increased risk for second malignant neoplasms (SMN) in those with hereditary disease 2-6, little is known about their long-term health.

The current study was designed to fill this gap by characterizing long-term medical outcomes among adult Rb survivors. The objectives of this study were to (1) determine the prevalence and excess risk of any chronic medical condition in adult Rb survivors when compared to unaffected individuals of similar age, sex, and race/ethnicity; (2) delineate the prevalence and excess risk of non-ocular, non-SMN chronic conditions in adult Rb survivors, when compared to a non-Rb cohort; (3) identify factors associated with inferior long-term medical outcomes; and (4) report on the general health of Rb survivors.

Methods

The current study is modeled after the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS), a questionnaire-based, retrospective cohort study investigating the long-term health of over 14,000 survivors of childhood cancer diagnosed from 1970-1986 7, 8. The CCSS has shown that childhood cancer survivors, when compared to a sibling comparison group, exhibit excess premature treatment-related morbidity and mortality 9-11. While the CCSS includes survivors of a wide range of pediatric cancers, Rb survivors are not included in the cohort. We performed a descriptive, cross-sectional, self-report study of health among adult Rb survivors.

Study Population

Eligible participants were defined as living Rb survivors, treated in New York, who were at least 18 years of age at the time of study enrollment and able to provide informed consent. Survivors were identified via the Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) and National Cancer Institute (NCI) databases (n=987). The study was approved by the MSK and NCI Institutional Review Boards/Privacy Boards.

Eligible participants were sent an introductory mailing that included an invitation for participation, an informed consent form, a survey packet, and a self-addressed, pre-stamped envelope by mail. Participants were contacted by telephone two weeks after mailing to ascertain interest in participation and were given the option of completing the survey by telephone or by mail, depending on participant preference. In total, 366 (77.9%) surveys were completed by mail. Enrollment occurred from March 2008-February 2011.

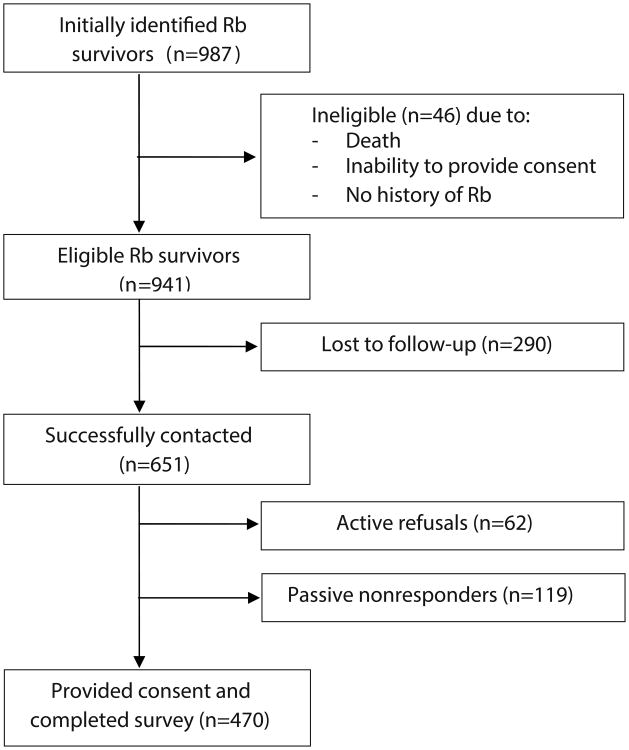

Despite repeated utilization of advanced tracing methods among 987 identified Rb survivors, we were unable to locate or contact 290 (29.3%) survivors. An additional 46 patients were found to be ineligible for reasons including: never having been diagnosed with Rb (n=15), death (n=11), and inability to provide consent due to significant cognitive impairment (n=8), language barrier (n=5), or miscellaneous reasons such as incarceration or emotional difficulties (n=5). Among the remaining 651 subjects, 470 consented and completed the questionnaire; 72.2% of those who were contacted and found to be eligible participated (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Participation and Contact in the Retinoblastoma (Rb) Survivor Study.

To provide a comparison population that had not been treated for cancer, responses were compared to those obtained from the CCSS sibling cohort7, a random sample of CCSS participants' nearest age, living siblings who also completed CCSS questionnaires. None of these individuals were siblings of Rb survivors. Rather, CCSS siblings who completed the CCSS Follow-Up 4 questionnaire (administered from July 2007-November 2009) were included as a control group (i.e., “non-Rb controls”). Self-reported data from 2,377 comparison individuals were included.

Outcome Measure

Rb survivors completed a comprehensive survey that was adapted from CCSS questionnaires 8, 12 and supplemented with questions of specific interest to Rb survivors (ie, a validated instrument that measures vision-related health status in those with chronic eye diseases13). A copy of the survey is available upon request. The survey included items that assessed sociodemographic factors; chronic medical conditions 9; health status 14; and visual impairment 13. Rb survivor responses were compared to previously collected CCSS sibling data, which did not include supplementary visual information. Data on survivors' health status, particularly in relation to visual functioning, will be reported elsewhere.

Severity of chronic conditions was coded using the NCI's Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE version 4.03) 15, a scoring system used to grade acute and chronic conditions in cancer patients and survivors as: mild (grade 1), moderate (grade 2), severe or disabling (grade 3), life-threatening (grade 4), or fatal (grade 5). There were no reported grade 5 conditions since all participants and controls were alive at the time of study entry. If adequate information to distinguish between grades was unavailable, the lower score was used.

Treatment History

Treatment history was abstracted from the NCI and MSK databases. Chemotherapy exposure was recorded as a yes/no/unknown variable; for those treated with chemotherapy, the names of specific agents were abstracted. Treatment with radiotherapy therapy was categorized as a binary yes/no variable; details on type of radiotherapy (brachytherapy, external beam radiotherapy, or both) were abstracted. All treatment data refers to therapy administered for treatment of primary or metastatic Rb; details of SMN-directed therapy were not available.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of survey respondents were described, using summary statistics and frequency counts, between Rb survivors (stratified by laterality) and the non-Rb controls. Differences between groups were examined by the non-parametric Wilcoxon Rank-sum test for continuous variables or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. The prevalence of: (1) any chronic condition and (2) non-ocular/non-SMN chronic conditions among Rb survivors and non-Rb controls was determined. For each analysis, three dichotomous outcome variables were assessed: (a) indication of any condition; (b) indication of grade 3-4 conditions; (c) multiple chronic conditions. For participants who had more than one chronic condition, the maximum grade of that condition was used. Tabulation of chronic conditions was censored at the time of SMN diagnosis for Rb survivors and primary cancer diagnosis for non-Rb controls. All included SMNs were pathologically verified. SMN and oculo-visual outcomes, such as cataracts, glaucoma, double vision and blindness, were excluded from the second analysis, which focused solely on non-ocular, non-SMN chronic conditions 2, 3.

To compare the prevalence of chronic conditions between Rb survivors and non-Rb controls, Poisson regression with robust variance estimates was used to estimate the relative risk (RR) ratios and their corresponding confidence intervals. Analyses were adjusted for age at study, sex, and race/ethnicity 16.

Multivariate Poisson regression was used to evaluate differences in severe/disabling or life-threatening conditions, and the two most common grade 3-4 chronic conditions, within Rb survivors according to Rb-directed treatment received.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.2 (SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and two-sided statistical inferences were employed throughout the analyses.

Results

Comparisons of Rb Survivor Participants and Non-Participants

When comparing baseline demographics of eligible Rb survivors who did or did not participate in the study, participants were more likely to be older at the time of study (median 48 years versus 46 years, p=0.02), female (52.1% versus 43.7%, p<0.01), and have a history of bilateral disease (53.6% versus 46.3%, p=0.02). There was no difference in age at Rb diagnosis among those who participated and those who did not.

Comparisons of Rb Survivors and the non-Rb Controls

Characteristics of survivors and non-Rb controls are shown in Table 1. Rb survivors were older at the time of study than controls (p<0.001), were less likely to be white, non-Hispanic (<0.001), and were more likely to report a lower household income (p<0.001). The two groups did not differ significantly in terms of sex, health insurance status, or highest level of education attained.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Adult Retinoblastoma (Rb) Survivors and a Non-Rb Control Group.

| Characteristics | All Rb Survivors (n=470) | Bilateral Survivors (n=252) | Unilateral Survivors (n=218) | Non-Rb Controls (n=2377) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at study, y, mean (Std) | 43.3 (11.0) | 42.5 (10.8) | 44.4 (11.0) | 37.6 (8.6) | <0.001 |

| Sex, No. (%) | 0.51 | ||||

| Male | 225 (47.9) | 127 (50.4) | 98 (44.9) | 1097 (46.2) | |

| Female | 245 (52.1) | 125 (49.6) | 120 (55.1) | 1280 (53.8) | |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 406 (86.4) | 221 (87.7) | 185 (84.9) | 2117 (89.0) | |

| Other group | 62 (13.2) | 30 (11.9) | 32 (14.7) | 177 (7.5) | |

| Don't know/missing | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 83 (3.5) | |

| Health insurance, No. (%) | 0.07 | ||||

| Yes or Canadian resident | 416 (88.5) | 228 (90.4) | 188 (86.2) | 2163 (91.0) | |

| No | 52 (11.1) | 23 (9.2) | 29 (13.3) | 199 (8.4) | |

| Don't know/missing | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 15 (0.6) | |

| Household income, No. (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| <$20,000/year | 45 (9.6) | 32 (13.5) | 13 (6.5) | 120 (5.1) | |

| ≥$20,000/year | 392 (83.4) | 205 (86.5) | 187 (93.5) | 2095 (88.1) | |

| Don't know/missing | 33 (7.0) | 15 (5.9) | 18 (8.3) | 162 (6.8) | |

| Education, No. (%) | 0.16 | ||||

| Complete high school or below | 64 (13.8) | 36 (14.5) | 28 (13.1) | 274 (11.5) | |

| Post-high school graduate or some college training | 394 (85.1) | 209 (83.5) | 185 (86.5) | 2100 (88.3) | |

| Missing | 12 (2.6) | 7 (2.7) | 5 (2.3) | 3 (0.1) | |

Comparisons between all Rb survivors and the non-Rb control group; responses coded as “don't know/missing” were excluded in the p-value calculations

Treatment Characteristics of Rb Survivors

Among Rb survivors, 26.0% were treated with any chemotherapy and 56.5% were treated with any radiotherapy (Table 2). Treatment with radiotherapy differed markedly by laterality; radiotherapy was administered to 91.7% of bilateral survivors and 15.7% of unilateral survivors, p<0.01.

Table 2. Treatment Characteristics of Retinoblastoma (Rb) Survivors, by Laterality.

| Characteristics | All Rb Survivors (n=470) | Unilateral (n=218) | Bilateral (n=252) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiation Therapy (RT) | <0.01 | |||

| Yes | 265 (56.5) | 34 (15.7) | 231 (91.7) | |

| No | 200 (42.6) | 180 (83.0) | 20 (7.9) | |

| Unknown | 4 (0.9) | 3 (1.3) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Type of RT (n=265) | <0.01 | |||

| Brachytherapy | 8 (3.0) | 3 (1.1) | 5 (1.9) | |

| External | 224 (84.5) | 28 (10.6) | 196 (73.9) | |

| External/Brachytherapy | 29 (11.0) | 1 (0.4) | 28 (10.6) | |

| Unspecified | 4 (1.5) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | |

| Chemotherapy | <0.01 | |||

| Yes | 119 (26.0) | 25 (11.5) | 94 (37.3) | |

| No | 347 (74.0) | 190 (87.6) | 157 (62.3) | |

| Unknown | 3 (0.6) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Type of Chemotherapy* | ||||

| EM | 74 (62.2) | 6 (27.3) | 68 (76.4) | |

| Cyclophosphamide | 33 (27.7) | 16 (72.7) | 17 (19.1) | |

| Nitrogen mustard | 2 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Non-alkylating agent | 30 (27.0) | 14 (63.6) | 16 (17.9) | |

Abbreviation: TEM=triethylene melamine

111 Rb survivors with complete chemotherapy data (22 with history of unilateral disease and 89 with history of bilateral disease)

Among Rb survivors treated with systemic chemotherapy, 95.5% had received at least one alkylating agent, which included triethylene melamine [TEM] (62.2%), cyclophosphamide (27.7%), and/or nitrogen mustard (1.7%) [Table 2]. None of the participants had documented exposure to a platinum agent. Survivors of bilateral disease were more likely to have received chemotherapy than survivors of unilateral disease (p<0.01).

Fifty-eight Rb survivors had at least one pathologically confirmed SMN (grade 3-4), which excluded nonmelanoma skin cancer, at a median age of 40.5 years (range, 5–70 years). Supplementary Table 1 outlines the distribution of SMN in the 58 affected Rb survivors.

General Health of Rb Survivors

Rb survivors were asked to provide self-reported ratings of their general health (“excellent,” “very good,” “good,” “fair” or “poor”). The vast majority of survivors (94.4%) described their health as “good” (24.2%), “very good” (40.0%), or “excellent” (28.9%) versus fair (4.9%) or poor (0.6%). A greater proportion of unilateral patients, when compared to bilateral patients, described their health as good to excellent (unilateral 98.1%; bilateral 91.2%; p<0.01).

Overall Risk of Chronic Medical Conditions: Comparison of Rb Survivors, by laterality, and the non-Rb Controls

Table 3a summarizes the risk of a chronic health condition of any grade among the Rb survivor cohort (stratified by laterality) and non-Rb controls.

Table 3. a. Any Chronic Health Condition (including Ocular Outcomes and SMN) in Adult Survivors of Rb *.

| Health Condition** | All Rb Survivors (n=470) | Unilateral Survivors (n=218) | Bilateral Survivors (n=252) | Non-Rb Controls (n=2377) | All Rb Survivors vs. Non-Rb Controls RR (95% CI)† | Unilateral Survivors vs. Non-Rb Controls RR (95% CI)† | Bilateral Survivors vs. Non-Rb Controls RR (95%CI)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any condition | |||||||

| Grades 1–4 | 407 (86.6) | 171 (78.4) | 236 (93.7) | 1381 (58.1) | 1.4 (1.3–1.4) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 1.5(1.4–1.6) |

| Grades 3–4 | 334 (71.1) | 133 (61.0) | 201 (79.8) | 195 (8.2) | 7.6 (6.4–8.9) | 5.7(4.6–7.1) | 8.3 (7.0–9.7) |

| Multiple health conditions (Grades 1–4) | |||||||

| ≥2 | 297 (63.2) | 113 (51.8) | 184 (73.0) | 714 (30.0) | 1.8 (1.6–2.0) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 2.1 (1.9 –2.4) |

| b. Non-Ocular/Non-SMN Chronic Health Conditions in Adult Survivors of Rb* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HealthCondition** | All Rb Survivors (n=470) | Unilateral Survivors (n=218) | Bilateral Survivors (n=252) | Non-Rb Controls (n=2377) | All Rb Survivors vs. Non-Rb Controls RR (95% CI)† | Unilateral Survivors vs. Non-Rb Controls RR (95% CI)† | Bilateral Survivors vs. Non-Rb Controls RR (95%CI)† |

| Any condition | |||||||

| Grades 1–4 | 320 (68.1) | 132 (60.5) | 188 (74.6) | 1314 (55.3) | 1.1 (1.02–1.2) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) |

| Grades 3–4 | 55 (11.7) | 17 (7.8) | 38 (15.1) | 142 (6.0) | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 1.7 (1.2–2.5) |

| Multiple health conditions (Grades 1–4) | |||||||

| ≥2 | 212 (45.1) | 74 (33.9) | 138 (54.7) | 671 (28.2) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) |

Abbreviations: Rb=retinoblastoma; SMN=second malignant neoplasm; RR=relative risk; CI=confidence interval

The severity of health conditions was scored according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.03)

All survivors and members of the non-Rb control group were alive at the time of study entry, thus no Grade 5, or fatal, conditions at the time of study

Comparisons between survivors and non-Rb controls were adjusted for age at enrollment, sex, and race/ethnicity

a. Risk in the overall Rb survivor cohort

With a median follow-up of 42 years (range, 15-75), 407 (86.6%) Rb survivors had a chronic health condition of any grade, and 334 (71.1%) had a severe, disabling, or life-threatening (grade 3-4) condition. Non-Rb controls reported fewer chronic conditions with 58.1% reporting any chronic condition and 8.2% reporting a grade 3-4 condition.

After adjusting for age at study, sex, and race/ethnicity, the relative risk of a survivor having any chronic condition, when compared with non-Rb controls, was 1.4 (95% CI, 1.3–1.4, p<0.01), while the relative risk of a grade 3-4 chronic condition was 7.6 (95% CI, 6.4–8.9, p<0.01). Rb survivors were 1.8 times more likely to have two or more chronic health conditions (95% CI, 1.6–2.0, p<0.01), when compared with non-Rb controls (Table 3a).

b. Risk by laterality

Within the Rb survivor cohort, the proportion of chronic conditions differed significantly by laterality with 78.4% of unilateral patients and 93.7% of bilateral patients reporting a chronic condition of any grade (p<0.01), and 61.0% of unilateral patients and 79.8% of bilateral patients reporting a grade 3-4 chronic condition (p<0.01) [see Table 3a].

When compared to non-Rb controls of similar age, sex, and race/ethnicity, Rb survivors were at increased risk for the development of any chronic condition regardless of laterality (RR 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1–1.3, p<0.01, for unilateral survivors; RR 1.5; 95% CI, 1.4–1.6, p<0.01, for bilateral survivors). Similarly, Rb survivors with a history of unilateral disease (RR 5.7; 95% CI, 4.6–7.1, p<0.01) and bilateral disease (RR 8.3; 95% CI, 7.0–9.7, p<0.01) were both at increased risk for the development of a grade 3-4 chronic condition, in comparison with non-Rb controls. Those with a history of bilateral disease had a higher risk of reporting these adverse outcomes than did those with a history of unilateral disease, when compared to non-Rb controls.

Risk of Non-Ocular, Non-SMN Chronic Medical Conditions: Comparison of Rb Survivors, by laterality, and Non-Rb Controls

a. Risk in the overall Rb survivor cohort

Given the paucity of data on long-term medical outcomes other than SMN and oculo-visual conditions in adult Rb survivors, a separate analysis focusing only on non-ocular, non-SMN conditions was performed. Among 470 adult Rb survivors, 68.1% reported at least one non-ocular, non-SMN chronic condition of any grade and 11.7% reported a grade 3-4 non-ocular, non-SMN condition (Table 3b). In contrast, 55.3% of non-Rb controls reported a non-ocular, non-SMN condition of any grade, and 6.0% reported a grade 3-4 non-ocular, non-SMN condition.

The adjusted relative risk of a non-ocular, non-SMN condition of any grade in an Rb survivor, when compared with non-Rb controls, was 1.1 (95% CI, 1.02–1.2, p<0.01); the risk of multiple non-ocular, non-SMN conditions was 1.3 (95% CI, 1.1–1.5, p<0.01). However, there was no excess risk of a grade 3-4 non-ocular, non-SMN chronic condition in Rb survivors (RR 1.3; 95% CI, 0.9–1.8, p=0.19), when compared with non-Rb controls.

b. Risk by laterality

After stratifying Rb survivors by laterality, we found that survivors of bilateral disease were more likely to report a non-ocular, non-SMN chronic condition of any grade (RR 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1–1.3, p<0.01); a grade 3-4 non-ocular, non-SMN chronic condition (RR 1.7; 95% CI, 1.2–2.5, p<0.01); and multiple non-ocular, non-SMN conditions of any grade (RR 1.6; 95% CI, 1.4–1.8, p<0.01), when compared with non-Rb controls. In contrast, survivors of unilateral disease were not at increased risk for any of these outcomes (see Table 3b).

Most Common Grade 3-4 Non-Ocular, Non-SMN Chronic Conditions within the Rb Survivor Cohort

The two most common grade 3-4 non-ocular, non-SMN conditions among Rb survivors were loss of hearing and suspicious thyroid nodules requiring partial or total thyroidectomy. Among the 15 Rb survivors who developed grade 3-4 severe hearing loss, 73.3% (n=11) received radiotherapy and 20% (n=3) received non-platinum chemotherapy. Among the 12 Rb survivors who developed grade 3 thyroid nodules, 75% (n=9) received radiotherapy and 41.7% (n=5) received chemotherapy. Eighty-seven percent of those who developed severe hearing loss and 83% of those who developed grade 3 thyroid nodules had a history of bilateral disease.

Predictors of Risk for the Development of Grade 3-4 Chronic Conditions: Overall and Non-Ocular, Non-SMN

a. Impact of treatment exposures and age at enrollment

In multivariate models, exposure to radiotherapy and increasing age at study were found to predict increased risk for the development of any grade 3-4 chronic condition (RR 1.2; 95% CI, 1.01–1.3, p=0.01 for radiation exposure; RR 1.1; 95% CI, 1.01–1.1, p=0.01 for older age at study) [see Table 4a]. Exposure to chemotherapy alone was not a predictor of increased risk (RR 1.1; 95% CI, 0.98–1.3, p=0.09).

Table 4. a. Predictors of Grade 3-4 Chronic Health Conditions in Adult Survivors of Rb.

| RR (95%CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Radiation therapy | 0.03 | |

| Yes | 1.2 (1.01–1.3) | |

| No (reference) | 1.0 | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.09 | |

| Yes | 1.1 (0.98–1.3) | |

| No (reference) | 1.0 | |

| Age at study* | 1.1 (1.01–1.1) | 0.01 |

| b. Predictors of Grade 3-4 Non-Ocular, Non-SMN Chronic Health Conditions in Adult Survivors of Rb | ||

|---|---|---|

| RR (95%CI) | p-value | |

| Radiation therapy | 0.07 | |

| Yes | 1.7 (0.9–2.8) | |

| No (reference) | 1.0 | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.64 | |

| Yes | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | |

| No (reference) | 1.0 | |

| Age at study* | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | <0.01 |

Abbreviations: Rb=retinoblastoma; RR=relative risk; CI=confidence interval

Estimating 10 year increments of age

When these same factors were examined in relation to the development of a grade 3-4 non-ocular, non-SMN condition, Rb-directed therapeutic exposures were not found to increase survivors' risk for these outcomes (Table 4a). However, there was a trend towards significance for those previously exposed to radiotherapy (RR 1.7; 95% CI, 0.9–2.8, p=0.07). Older patients at the time of study were more likely to report a grade 3-4 non-ocular, non-SMN chronic condition (RR 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2–1.9, p<0.01), compared to younger patients.

b. Impact of low visual acuity

The impact of low visual acuity on grade 3-4 non-ocular, non-SMN chronic condition risk was explored as well. A significantly greater percentage of those with grade 3-4 vision loss reported a severe, disabling, or life-threatening non-ocular, non-SMN condition, when compared to those with grades 0, 1 or 2 vision loss (14.1% versus 7.8%, p=0.04).

In multivariate analyses adjusting for age at enrollment, exposure to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, Rb survivors with grade 3-4 vision loss were no more likely to report a grade 3-4 non-ocular, non-SMN condition than those with grades 0, 1 or 2 vision loss (RR 1.6; 95% CI, 0.9–2.6,p=0.09).

Discussion

This is the largest study to date to assess medical outcomes and general health of adult Rb survivors. While extensive data exist on the risk of SMN 3-6, 17 and oculo-visual outcomes 18-22 in Rb survivors, there is a paucity of information on chronic medical conditions in this population. In the current report, we found that adult Rb survivors were 1.4 times more likely to report any chronic condition, and 7.6 times more likely to have a severe or life-threatening chronic condition, when compared to a similarly aged cohort of individuals without a history of Rb. Notably, Rb survivors were also more likely to develop multiple chronic conditions compared to controls. This excess risk was evident for Rb survivors regardless of laterality, although those with bilateral disease were at greater risk than those with unilateral disease.

Existing data on long-term medical outcomes in Rb survivors are limited. One report on medical outcomes in 21 Rb survivors found the most frequent late effects to be post-radiotherapy orbital deformation23. Another study on health-related quality of life in Swiss childhood cancer survivors reported on 37 Rb survivors finding lower scores in the Physical Component Summary when compared to other childhood cancer survivors 24. Van Dijk 25-28 and others 21, 29 have studied psychosocial, behavioral, and functional outcomes in Rb survivors, but have not described survivors' treatment-related medical chronic conditions.

Other reports have demonstrated similar excess risks of chronic conditions in non-Rb childhood cancer survivors. In a landmark study of over 10,000 adult survivors of childhood cancer from the CCSS, non-Rb cancer survivors were found to have a 3.3-fold increased risk of developing a chronic condition and an 8.2-fold increased risk of a grade 3-4 condition, when compared to unaffected siblings (who also comprise the control group in the current report) 9. More recently, Armstrong et al reported that the cumulative incidence of a grade 3-5 health condition among childhood cancer survivors by age 50 was 53.6% 30. While the risk of serious chronic conditions is modestly higher in the CCSS survivor cohort than in the Rb cohort reported here, it is important to note that we censored survivors at the time of SMN diagnosis, while the CCSS report did not.

Given that Rb survivors' non-ocular, non-SMN medical outcomes have been under-studied, we conducted a separate analysis of these outcomes. We found that Rb survivors were more likely to develop a non-ocular, non-SMN chronic condition of any grade, when compared to non-Rb controls, but were not more likely to develop a grade 3-4 non-ocular, non-SMN condition. Importantly, the excess risk of developing non-ocular, non-SMN chronic conditions in Rb survivors was confined to those with a history of bilateral disease.

Encouragingly, despite these excess risks, the vast majority of adult Rb survivors reported good to excellent health. As expected, significantly fewer patients with a history of bilateral disease reported good to excellent health, when compared to subjects with unilateral disease. This inferior self-perceived general health may be attributed to bilateral patients' excess chronic condition risk, higher lifelong risk of SMN, and/or morbidities related to additional more intensive therapies.

The present analysis has some limitations that must be considered when interpreting the study results. First, with the exception of SMNs, which were pathologically verified, chronic conditions and ratings of general health were self-reported by survivors and were not externally validated. Second, the cohort included only survivors who were alive at the time of the survey; surrogates for those who had died were not included, which may have led to under-reporting of serious medical conditions. Third, we were unable to include radiation or chemotherapy doses in the analysis, which would have allowed us to examine the impact of treatment exposures more closely. Additionally, since details of SMN-directed therapies were not available, we could not account for the impact of these therapies and thus censored all Rb survivors at the time of SMN diagnosis. Lastly, survivors included in the current study were treated in an era when radiotherapy was more frequently used.

Contemporary patients are less likely to receive radiotherapy and more likely to receive chemotherapy (either intravenous or intra-arterial) with different agents from those used in this cohort. Notably, none of the survivors in this cohort had documented exposure to platinum agents, including those with severe hearing loss. The lack of association between exposure to chemotherapy and risk of chronic conditions in our cohort is likely due to the small number of survivors so treated. Assessment of survivors treated with chemotherapy as it is used in more contemporary protocols will be required to detect its true impact on the risk of chronic conditions. Nonetheless, this cohort provides important historical data that may be used as a benchmark for future studies on late effects in Rb survivors.

This study is the first to show that adult Rb survivors have an increased risk of chronic conditions, when compared to non-Rb controls of similar age, sex, and race/ethnicity. This excess risk is largely driven by those with a history of bilateral disease. Information from the present report can be utilized to inform risk based-screening guidelines for the long-term follow-up of adult Rb survivors. Our data suggest that healthcare providers should perform careful skin and thyroid examinations; focus on signs and symptoms related to SMN in those with hereditary disease; consider audiologic evaluations when indicated; and co-manage ocular problems with an experienced ophthalmic oncologist. Special attention should be given to those with a history of bilateral disease. Late effects related to newer treatment modalities will need to be delineated by assessing late outcomes in more contemporarily treated patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Joseph Olechnowicz for his editorial contributions.

Funding: This study was supported by the New York Community Trust, the Frueauff Foundation, Perry's Promise Fund, National Cancer Institute [NCI] grant U24 CA55727 (CCSS, GT Armstrong, PI), grant KL2TR000458 of the Clinical and Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell (DN Friedman, PI), and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health [NIH], NCI; KCO is supported in part by the NIH (K05CA160724). Biostatistical support to Memorial Sloan Kettering was supported by P30CA008748.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

References

- 1.Howlader N, N A, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations) based on November 2011 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2012. [accessed April 23, 2013]; Available from URL: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/

- 2.Wong FL, Boice JD, Jr, Abramson DH, et al. Cancer incidence after retinoblastoma. Radiation dose and sarcoma risk. JAMA. 1997;278:1262–1267. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.15.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleinerman RA, Tucker MA, Tarone RE, et al. Risk of new cancers after radiotherapy in long-term survivors of retinoblastoma: an extended follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2272–2279. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleinerman RA, Tucker MA, Abramson DH, Seddon JM, Tarone RE, Fraumeni JF., Jr Risk of soft tissue sarcomas by individual subtype in survivors of hereditary retinoblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:24–31. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleinerman RA, Schonfeld SJ, Tucker MA. Sarcomas in hereditary retinoblastoma. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2012;2:15. doi: 10.1186/2045-3329-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francis JH, Kleinerman RA, Seddon JM, Abramson DH. Increased risk of secondary uterine leiomyosarcoma in hereditary retinoblastoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD, et al. Study design and cohort characteristics of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: a multi-institutional collaborative project. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38:229–239. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leisenring WM, Mertens AC, Armstrong GT, et al. Pediatric Cancer Survivorship Research: Experience of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:2319–2327. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mertens AC, Liu Q, Neglia JP, et al. Cause-specific late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1368–1379. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong GT, Liu Q, Yasui Y, et al. Late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: a summary from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2328–2338. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Boice JD, et al. The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: A National Cancer Institute–Supported Resource for Outcome and Intervention Research. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:2308–2318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mangione CM, Lee PP, Gutierrez PR, Spritzer K, Berry S, Hays RD. Development of the 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1050–1058. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.7.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Yasui Y, et al. Health status of adult long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA. 2003;290:1583–1592. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Program CTE. Common terminology criteria for adverse events, version 4.03. [accessed April 24, 2013]; Available from URL: http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_8.5x11.pdf.

- 16.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong JR, Morton LM, Tucker MA, et al. Risk of subsequent malignant neoplasms in long-term hereditary retinoblastoma survivors after chemotherapy and radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3284–3290. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.7844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peylan-Ramu N, Bin-Nun A, Skleir-Levy M, et al. Orbital growth retardation in retinoblastoma survivors: work in progress. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;37:465–470. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaste SC, Chen G, Fontanesi J, Crom DB, Pratt CB. Orbital development in long-term survivors of retinoblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1183–1189. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ek U, Seregard S, Jacobson L, Oskar K, Af Trampe E, Kock E. A prospective study of children treated for retinoblastoma: cognitive and visual outcomes in relation to treatment. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002;80:294–299. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2002.800312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desjardins L, Chefchaouni MC, Lumbroso L, et al. Functional results after treatment of retinoblastoma. J AAPOS. 2002;6:108–111. doi: 10.1067/mpa.2002.121451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abramson DH, Melson MR, Servodidio C. Visual fields in retinoblastoma survivors. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:1324–1330. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.9.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nahum MP, Gdal-On M, Kuten A, Herzl G, Horovitz Y, Weyl Ben Arush M. Long-term follow-up of children with retinoblastoma. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;18:173–179. doi: 10.1080/08880010151114769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rueegg CS, Gianinazzi ME, Rischewski J, et al. Health-related quality of life in survivors of childhood cancer: the role of chronic health problems. J Cancer Surviv. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Dijk J, Oostrom KJ, Imhof SM, et al. Behavioural functioning of retinoblastoma survivors. Psychooncology. 2009;18:87–95. doi: 10.1002/pon.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Dijk J, Oostrom KJ, Huisman J, et al. Restrictions in daily life after retinoblastoma from the perspective of the survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54:110–115. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Dijk J, Imhof SM, Moll AC, et al. Quality of life of adult retinoblastoma survivors in the Netherlands. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:30. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Dijk J, Grootenhuis MA, Imhof SM, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Moll AC, Huisman J. Coping strategies of retinoblastoma survivors in relation to behavioural problems. Psychooncology. 2009;18:1281–1289. doi: 10.1002/pon.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weintraub N, Rot I, Shoshani N, Pe'er J, Weintraub M. Participation in daily activities and quality of life in survivors of retinoblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56:590–594. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armstrong GT, Kawashima T, Leisenring W, et al. Aging and risk of severe, disabling, life-threatening, and fatal events in the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1218–1227. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.