Abstract

Background

Hibernators such as the 13-lined ground squirrel endure severe hypothermia during torpor followed by periodic rewarming during interbout arousal (IBA), pro-apoptotic conditions that are lethal to non-hibernating mammals. We have previously shown that 13-lined ground squirrel tubular cells are protected from apoptotic cell death during IBA. To understand the mechanism of protection, we developed an in vitro model of prolonged cold storage followed by rewarming (CS/REW), which is akin to the in vivo changes of hypothermia followed by rewarming observed during IBA. We hypothesized that renal tubular epithelial cells (RTECs) isolated from hibernating ground squirrels would be protected against apoptosis during CS/REW, vs. non-hibernating mouse RTECs.

Methods

Isolated hibernating ground squirrel and mouse RTECs were subjected to cold storage at 4°C for 24 hours followed by rewarming to 37°C for 24 hours (CS/REW).

Results

Ground squirrel RTECs had significantly less apoptosis compared to mouse RTECs when subjected to CS/REW. Next, we hypothesized that the mechanism of protection was related to the anti-apoptotic proteins XIAP, pAkt and pBAD. There was significantly increased pAkt and pBAD expression in ground squirrel vs. mouse RTECs subjected to CS/REW. XIAP expression was maintained in ground squirrel RTECs but was significantly decreased in mouse RTECs following CS/REW. Ground squirrel RTECs in which gene expression of Akt1 and XIAP was silenced lost their protection and demonstrated increased apoptosis & cleaved capase-3 expression following CS/REW.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that ground squirrel RTECs are protected against apoptosis during prolonged CS/REW by the ‘pro-survival’ factors XIAP and pAkt.

INTRODUCTION

During hibernation, mammals such as the 13-lined ground squirrel undergo extreme reductions in core body temperature (CBT) from 38°C to ~ 4°C for up to 18 days during torpor (1). Torpor is periodically interrupted by rewarming of organs to 38°C for ~ 24 hours during interbout arousal (IBA) (1). The hibernator then re-enters torpor and cycles through torpor-arousal ~ 20 times in a winter season (1).

Several features of torpor-arousal are pro-apoptotic and lethal to non-hibernators (2, 3), such as hypothermia (4, 5), and warm reperfusion (3, 6, 7). Thus hibernation has the potential to induce apoptosis in at risk-organs such as the kidney, which has been described as being on the verge of anoxia (8–10).

We have previously shown that mouse kidneys and isolated tubular cells subjected to prolonged ex vivo cold storage and rewarming have increased caspase-3 protein expression and increased tubular cell apoptosis (11, 12). Human kidneys also demonstrate increased caspase-3 protein expression and increased tubular cell apoptosis during both prolonged ex vivo cold storage (5), and during cold storage followed by rewarming after transplantation (4).

We have also shown that in contrast, renal tubular epithelial cell (RTEC) apoptosis is largely absent in 13-lined ground squirrel kidneys, despite exposure to the pro-apoptotic conditions of prolonged hypothermia followed by rewarming during IBA (13). The mechanism by which RTEC apoptotic cell death is prevented during hypothermia followed by rewarming is unknown, but has been linked to increased protein expression of anti-apoptotic proteins such as Akt (3), and to prevention of capsase-3 activation (13).

We therefore hypothesized that RTECs isolated from hibernating ground squirrel kidneys would be protected from apoptosis under conditions of hypothermia and rewarming, by the anti-apoptotic proteins pAkt, pBAD and XIAP, the most potent naturally occurring inhibitor of caspase-3(14). The first aim of this study was to examine the expression of pAkt, pBAD and XIAP in isolated ground squirrel RTECs, in an in vitro model of cold storage followed by rewarming that is akin to conditions encountered by hibernating ground squirrels.

The second aim of this study was to determine the effect of XIAP or pAkt inhibition on apoptotic cell death of ground squirrel RTEC. We hypothesized that isolated ground squirrel RTECs subjected to cold storage followed by rewarming in vitro would be protected from apoptosis in association with upregulation of pAkt and XIAP. Furthermore, we hypothesized that inhibition of pAkt and XIAP during cold storage followed by rewarming would lead to loss of protection from apoptosis in isolated ground squirrel RTECs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

To isolate ground squirrel RTECs, ground squirrels were euthanized by cardiac exsanguination under deep isoflurane anesthesia during IBA as previously described (13). Kidneys from 1–2 year old male 13-lined ground squirrel kidney were harvested. Kidney cortex was incubated with collagenase and minced with sharp blade and then filtered through 0.2 micron filter. The filtrate was then centrifuged and washed with Dulbeco’s modified Eagles medium (DMEM)/F-12 50/50 medium x 3. Cells were plated in DMEM medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and kept at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 until they become confluent. Epithelial morphology of these cells was confirmed by cytokeratin k8 and βcatenin expression. Cell immortalization was carried out through the expression of Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase protein (TERT) using lentivirus marker supernatant: Lenti-hTert-GFP (Biogenova, LG508) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Immortalized RTECs of ground squirrels were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin and 100μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 and fed with fresh medium at intervals of 48 h.

Immortalized mouse renal tubular cells were used as a positive control from a non-hibernating species. Mouse renal tubular epithelial cells (RTECs) (15) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin and 100μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 and fed with fresh medium at intervals of 48 h.

CS/REW of RTECs

Experiments were performed with RTECs grown to 70–80% confluence. For CS/REW, normal growth media was replaced with University of Wisconsin (UW) solution and RTECs were subjected to cold storage (CS) for 24 h at 4°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Cold UW solution was then replaced with warm DMEM media containing FBS at 37°C (REW) and the RTECs were incubated at 37°C incubator for 24 h. Control RTECs were kept at 37°C degrees.

Since our in vitro model of CS/REW involves replacement of cold UW solution with warm media, it is possible that dead, detached cells in the UW solution may be removed and produces a selection bias in the data. To address this limitation we also performed CS/REW in media that was cooled for 24 h at 4°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2, and rewarmed back to 37°C (REW) in an incubator for 24 h. We therefore preserved dead cells, which were subsequently analyzed in viability assays.

Viability assay (Trypan blue exclusion assay)

Trypan Blue dye exclusion was used to determine cell viability (16). Briefly, after the RTECs were exposed to CS/REW, both floaters and attached (mild trypsinization ~ 2 minutes) RTECs were collected and washed twice with 1× PBS. The resulting cell pellet was then suspended in 1X PBS. An equal volume of trypan blue dye and cell pellet were mixed and quantification of cells was performed in quadruplicate per treatment (in 8 random fields per sample) to score live and dead cells using Nexcelom Automated Cell Counter. The cells were classified as follows: (i) viable cells - clear cytoplasm and (ii) nonviable cells- blue cytoplasm.

Cell lysis and western blot analysis

RTECs were lysed in RIPA buffer for 10 minutes on ice and then subjected to sonication for 10s. The lysate was centrifuged at 14,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay. Equal amounts of protein were separated on SDS-PAGE, transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, blocked, and incubated with primary antibodies of cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling, 9661), XIAP (Cell Signaling, 2042), Akt1 (Cell Signaling, 2938) pAkt Ser473 (Cell Signaling, 9271), or pBAD Ser136 (Cell Signaling, 4366) overnight at 4°C. After washing, the membrane was incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody. ECL was used as a method of detection. Each membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti β-actin antibody β-actin (Cell Signaling, 4970) to verify equal protein loading. Immunoblots for every protein were performed on samples from 4 separate, independent experiments for each condition to ensure reproducibility. To quantitate the results, densitometry and statistical analyses were performed. The densitometry values were adjusted to loading control (β-actin).

Mitochondrial Fractionation

After CS/REW, mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were isolated from RTECs using a mitochondrial fractionation kit (Active Motif, 100942) according to manufacturer’s directions. To verify equal protein loading COX IV (Cell Signaling, 4850) and α tubulin (Cell Signaling, 2144) were used as mitochondrial and cytosolic loading controls respectively.

Transfection of XIAP small interfering RNA (siRNA)

XIAP siRNA (Invitrogen, 4390824), was used to reduce the expression of XIAP in ground squirrel RTECs. Briefly, ground squirrel RTECs were plated in 60mm dishes in growth medium without antibiotics such that they were 80–85% confluent at the time of transfection. RTECs were transfected for 24 hours with XIAP 100 pmol siRNA or control nonspecific siRNA (Invitrogen, 4390843) with the transfection reagent lipofectamine2000™ (Invitrogen, 11668-019). RTECs were further exposed to CS/REW. After exposure to apoptotic stimuli, RTECs were harvested and analyzed for protein expression.

Transfection of Akt1 short hairpin RNA (shRNA)

Akt1 shRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 29195 v) was used to make a stable colony of ground squirrel RTECs in which gene expression of Akt1 was reduced. Briefly, ground squirrel RTECs were plated in 60mm dishes in growth medium without antibiotics to achieve 50% confluence at the time of transfection. Polybrene at a final concentration of 5μg/ml was added before adding lentiviral particles. RTECs were then infected by adding Akt1 shRNA lentiviral particles and incubated overnight. On the following day, cells were split in ratio 1:3 and further incubated for 48 hours in complete growth medium. To select stable clones expressing Akt1 shRNA, puromycin dihydrochloride selection was used. Complete medium with puromycin was replaced every 3–4 days until resistant colonies were identified. Several colonies were picked and expanded and assayed for stable shRNA expression. Colonies with 60–70% knockdown expression of Akt1 were picked for further study. RTECs derived from a colony with a stable knockdown of Akt1 (60–70%) colony were further exposed to CS/REW. After exposure to apoptotic stimuli, RTECs were harvested and analyzed for the expression of proteins.

Detection of Apoptosis

RTECs were grown in chamber slides for TUNEL assay. After stimulation of apoptosis (CS/REW), morphological assessment and TUNEL assay (Promega, G7130) were performed according to manufacturer’s directions. Positive and negative controls for TUNEL stain were performed. The number of TUNEL-positive and RTECs was counted by using a Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope equipped with a digital camera connected to SPOT ADVANCED 3.5 imaging software by an observer blinded to the treatment modality. At least 10 areas per sample were randomly selected. Morphologic assessment was performed by examining RTECs for cellular rounding and shrinkage, pyknotic nuclei, and formation of apoptotic bodies in a blinded fashion as previously described (17, 18). Apoptotic RTECs were identified as those that stained positive with TUNEL and also demonstrated apoptotic morphology as we have previously described (17, 18).

Statistical Analyses

All data and results presented were confirmed in at least 3–4 independent experiments. All values are expressed as means ± SE. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s Multiple Comparison Test or unpaired t test using GraphPad prism software version 5.01 (California, USA). A P value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Primary ground squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW in UW solution or media are protected from apoptosis compared to mouse RTECs

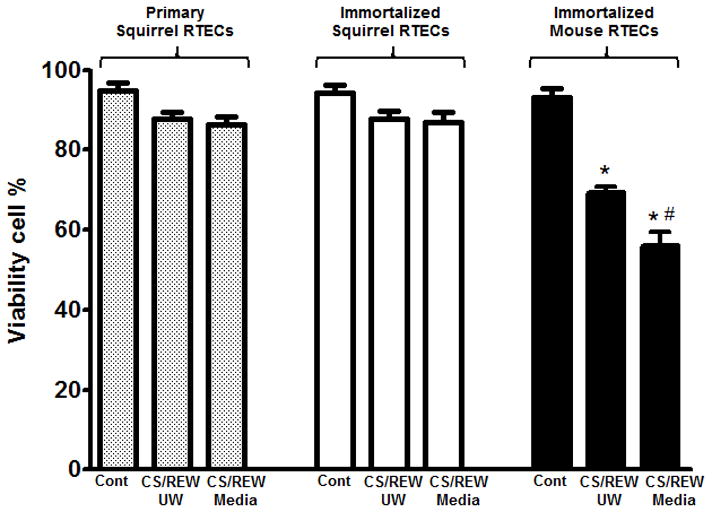

Primary ground squirrel RTECs isolated from kidney cortex (primary RTECs), immortalized squirrel RTECs (by lentiviral transduction) and mouse RTECs were subjected to an in vitro model of CS/REW. After treatment both floaters and attached RTECs were collected. There was no significant difference in percent viability in ground squirrel primary and immortalized RTECs subjected to CS/REW in UW solution or media versus their respective controls (Figure 1). Percent viability was significantly reduced in immortalized mouse RTECs subjected to CS/REW either in UW solution or in media (p<0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Primary and immortalized squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW in UW solution or media are protected from cell death. No significant difference was found in the percent viability of primary or immortalized squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW in UW solution or media compared to their respective controls. In contrast, percent viability was significantly reduced in immortalized mouse RTECs subjected to CS/REW in UW solution or media vs. mouse controls, and primary and immortalized squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW in UW solution or media (*p <0.001 vs. immortalized control mouse RTECs, primary control squirrel RTECs, immortalized control squirrel RTECs and primary and immortalized squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW in UW solution or media; #p <0.01 vs. immortalized mouse RTECs subjected to CS/REW in UW solution, n=4). Data are shown as means ± SE.

Ground squirrel RTECs are protected from apoptosis compared to mouse RTECs subjected to CS/REW

Ground squirrel primary or immortalized RTECs that were subjected to CS/REW had significantly fewer apoptotic cells versus immortalized mouse RTECs subjected to the same treatment (p<0.001) (Figure 2A–B). Immortalized squirrel RTECs and immortalized mouse RTECs are hereafter mentioned as squirrel and mouse RTECs respectively.

Figure 2.

Primary and immortalized squirrel RTECs are protected from apoptosis during CS/REW. (2A) Representative pictures of TUNEL staining in primary squirrel RTECs, immortalized squirrel RTECs and immortalized mouse RTECs exposed to CS/REW. Mouse RTECS demonstrate significantly increased TUNEL staining following CS/REW. (2B) No significant increase in percent apoptosis was observed in primary and immortalized squirrel RTECs exposed to CS/REW compared to their respective controls. In contrast, percent apoptosis was increased significantly in immortalized mouse RTECs subjected to CS/REW vs. mouse controls, and primary and immortalized squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW (*p <0.001 vs. immortalized control mouse RTECs, primary control squirrel RTECs, immortalized control squirrel RTECs and primary and immortalized squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW, n=4). Data are shown as means ± SE.

Protection of ground squirrel RTECs against CS/REW apoptosis is associated with increased expression of anti-apoptotic proteins

To determine whether the protection of ground squirrel RTECs from caspase-3 activation and apoptotic cell death during CS/REW was associated with an increase in anti-apoptotic proteins, we examined the expression of XIAP, pAkt (Ser473) and pBAD (Ser136) in RTECS subjected to CS/REW. Protein expression of pAkt (Ser473) and pBAD (Ser136) was significantly increased in ground squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW versus control ground squirrel RTECs and mouse RTECs subjected to CS/REW (Figure 3A–D). XIAP expression was maintained in ground squirrel RTECs following CS/REW, whereas XIAP expression was significantly decreased in mouse RTECs following CS/REW (Figure 3A and 3E).

Figure 3.

Protection of squirrel RTECs from apoptosis during CS/REW is associated with increased protein expression of XIAP, pAkt (Ser473) and pBAD (Ser136). (3A) Representative blots demonstrate increased pAkt (Ser473) and pBAD (Ser136) protein expression in squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW vs. control squirrel RTECs. XIAP protein expression persists in squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW. In contrast mouse RTECs subjected to CS/REW have reduced protein expression of the pAkt (Ser473), pBAD (Ser136) and XIAP vs. control mouse RTECs. (3B) The bar graphs represent densitometry values obtained from 4 independent experiments (see methods). Data are shown as means ± SE. No significant difference was found in Akt1 protein expression between squirrel and mouse RTECs. (3C) pAkt (Ser473) expression was significantly increased in squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW compared to control squirrel RTECs and mouse RTECs subjected to CS/REW (*p <0.001 vs. control squirrel RTECs and mouse RTECs subjected to CS/REW). (3D) pBAD (Ser136) expression was significantly increased in squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW compared to control squirrel RTECs and mouse RTECs subjected to CS/REW (*p <0.001 vs. control mouse RTECs and mouse RTECs subjected to CS/REW; #p <0.05 vs. control squirrel RTECs). (3E) XIAP expression remains persistent in squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW compared to control squirrel RTECs and mouse RTECs subjected to CS/REW (*p <0.001 vs. mouse RTECs subjected to CS/REW).

Ground squirrel RTECs deficient in Akt1 undergo apoptosis when subjected to CS/REW compared to untreated wild type ground squirrel RTECs

Akt1 gene expression was silenced to determine whether pAkt (Ser473) and pBAD (Ser136) were necessary for protection against CS/REW induced apoptotic cell death in ground squirrel RTECs. Akt1 shRNA was used to achieve a 60–70% reduction in Akt1 gene expression in ground squirrel RTECs (Figure 4A–B). Ground squirrel RTECs deficient in Akt1 and subjected to CS/REW had: (i) significantly decreased pAkt (Ser473) expression (Figure 4A and 4C) (ii) significantly reduced pBAD (Ser136) expression (Figure 4A and 4D) (iii) significantly increased cleaved caspase-3 protein expression (Figure 4A and 4E) and (iv) significantly increased apoptotic cells versus untreated wild type ground squirrel RTECs (p <0.001) (Figure 4F–G).

Figure 4.

Squirrel RTECs treated with Akt1 shRNA and then subjected CS/REW undergo apoptosis. (4A) Representative blots demonstrate reduced protein expression of Akt1 in squirrel RTECs treated with shRNA against Akt1. Squirrel RTECs deficient in Akt1 and exposed to CS/REW have decreased pAkt (Ser473), pBAD (Ser136) and increased cleaved caspase-3 protein expression compared to wild type control and wild type squirrel RTECs exposed to CS/REW. (4B) The bar graphs represent densitometry values obtained from 4 independent experiments (see methods). Data are shown as means ± SE. Akt1 expression was significantly reduced in squirrel RTECs treated with Akt1 shRNA compared to wild type squirrel RTECs (*p <0.001 vs. wild type squirrel RTECs). (4C) pAkt (Ser473) expression was significantly reduced in squirrel RTECs treated with Akt1 shRNA compared to wild type squirrel RTECs (*p <0.05 vs. wild type control squirrel RTECs; *p <0.001 vs. wild type squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW; #p <0.01 vs. wild type squirrel control RTECs). (4D) pBAD (Ser136) expression was significantly reduced in squirrel RTECs treated with Akt1 shRNA compared to wild type squirrel RTECs (*p <0.01 vs. wild type control squirrel RTECs and wild type squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW; #p <0.001 vs. wild type control squirrel RTECs). (4E) Cleaved caspase-3 expression was significantly increased in squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW and treated with Akt1 shRNA compared to wild type squirrel RTECs (*p <0.001 vs. wild type and Akt1 deficient control squirrel RTECs and wild type squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW). (4F) Representative pictures of TUNEL staining in wild type and Akt1 deficient squirrel RTECs exposed to CS/REW is shown. (4G) Squirrel RTECs deficient in Akt1 and exposed to CS/REW have significantly increased apoptotic cells compared to controls and wild type squirrel RTECs exposed to CS/REW. (*p <0.001 vs. wild type and Akt1 deficient control squirrel RTECs, and wild type squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW, n=4).

Ground squirrel RTECs deficient in XIAP undergo apoptosis when subjected to CS/REW compared to untreated wild type ground squirrel RTECs

XIAP expression was knocked down using siRNA. Ground squirrel RTECs treated with siRNA against XIAP followed by CS/REW had: (i) significantly decreased XIAP expression (Figure 5A–B) (ii) significantly increased cleaved caspase-3 protein expression (Figure 5A and 5C) and (ii) significantly (p <0.001) increased apoptotic cells vs. untreated wild type ground squirrel RTECs (Figure 5D–E).

Figure 5.

Squirrel RTECs treated with XIAP siRNA and then subjected CS/REW undergo apoptosis. (5A) Representative blots demonstrate reduced protein expression of XIAP in squirrel RTECs treated with XIAP siRNA. Squirrel RTECs treated with XIAP siRNA and exposed to CS/REW have decreased XIAP and increased cleaved caspase-3 protein expression compared to wild type control and wild type squirrel RTECs exposed to CS/REW. (5B) The bar graphs represent densitometry values obtained from 4 independent experiments (see methods). Data are shown as means ± SE. XIAP expression was significantly reduced in squirrel RTECs treated with XIAP siRNA compared to wild type squirrel RTECs (*p <0.001 vs. wild type squirrel RTECs) (5C) Cleaved caspase-3 expression was significantly increased in squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW and treated with XIAP siRNA compared to wild type squirrel RTECs (*p <0.001 vs. wild type, XIAP deficient control squirrel RTECs, and wild type squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW). (5D) Representative pictures of TUNEL staining in wild type and XIAP deficient squirrel RTECs exposed to CS/REW is shown. (5E) Squirrel RTECs deficient in XIAP and exposed to CS/REW have significantly increased apoptosis compared to controls and wild type squirrel RTECs exposed to CS/REW. (*p <0.001 vs. wild type and XIAP deficient control squirrel RTECs and wild type CS/REW squirrel RTECs, n=4).

XIAP is exclusively present in cytoplasm in ground squirrel and mouse RTECs when subjected to CS/REW

To determine the subcellular localization of XIAP, we subjected ground squirrel and mouse RTECs to mitochondrial separation following CS/REW. XIAP was exclusively found in cytosolic fraction in both squirrel and mouse RTECs (Figure 6). Furthermore, XIAP expression in the cytosolic fractions of both ground squirrel and mouse RTECS subjected to CS/REW mirrored the expression observed in whole cell lysates (Figure 3A). XIAP expression was maintained in ground squirrel RTECs following CS/REW, whereas XIAP expression was significantly reduced in mouse RTECs following CS/REW.

Figure 6. Subcellular localization of XIAP is cytoplasmic when RTECs were subjected to CS/REW.

Representative blots demonstrate XIAP was exclusively present in cytoplasmic fraction compared to mitochondrial fraction when squirrel and mouse RTECs were subjected to CS/REW. In cytoplasm XIAP expression remains persistent in squirrel RTECs subjected to CS/REW compared to mouse RTECs subjected to CS/REW.

DISCUSSION

Increased caspase-3 protein and tubular cell apoptosis are features of prolonged ex vivo cold of donor kidneys followed by transplantation. We have previously demonstrated an increase caspase-3 protein and tubular cell apoptosis in isolated renal tubular cells and mouse whole kidneys subjected to prolonged cold storage in UW solution in vitro and ex vivo (12, 13). Human kidneys also demonstrate increased caspase-3 protein and tubular cell apoptosis during prolonged ex vivo cold storage (5), and during cold storage followed by rewarming after transplantation (4). Hypothermia followed by rewarming is therefore a well-known pro-apoptotic stimuli in non-hibernating mammals (19).

Conversely, hibernating mammals are able to survive prolonged hypothermia followed by rewarming under conditions that would be lethal to non-hibernators (2, 13). We have previously shown that remarkably little tubular cell apoptosis occurs despite the prolonged hypothermia of torpor followed by rewarming during arousal in ground squirrels in vivo (13). Furthermore, we demonstrated that kidneys from 13-lined ground squirrels were protected from tubular cell apoptosis when subjected to prolonged ex vivo cold storage in UW solution, regardless of whether the kidneys were obtained from summer non-hibernating animals, or from hibernating torpid or aroused animals (13). We therefore surmised that protection of tubular cells during pro-apoptotic conditions of cold storage or rewarming was an intrinsic feature of 13-lined ground squirrel tubular cells. The mechanism of protection from apoptotic cell death during conditions of hypothermia and rewarming are unknown however. In our previous study (13) we were unable to investigate RTEC protection in a mechanistic fashion. Thirteen lined ground squirrels are outbred, and must be trapped before study. Therefore, only small colonies of ~ 20–25 animals can be studied each season.

In order to circumvent the limitations of a shortage of squirrels and to be able to knock out proteins to gain mechanistic insights into protection from CS/REW, we developed an in vitro model of CS/REW in isolated 13-lined ground squirrel tubular cells. We were thus able to study the specific effect of inhibition of XIAP and Akt1 during pro-apoptotic conditions of cold storage and rewarming in a manner that is not possible in vivo. Both primary and immortalized ground squirrel tubular cells are protected from apoptosis during CS/REW to the same degree and demonstrate no significant difference in viability. We therefore conclude that cell viability and protection from apoptosis during CS/REW is a feature of squirrel tubular cells that is independent of immortalization.

We focused on potential inhibitors of caspase-3 activation, namely X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) and Phospho Akt (Ser473). XIAP is a naturally occurring inhibitor of caspase-3 (14). XIAP belongs to the Inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) families, whose member’s binds and inhibit caspases 3, 7, and/or 9, but not caspase 8(20). XIAP is inhibited by HtrA2 (High temperature requirement protein A2), a mitochondrial serine protease released during mitochondrial injury (21). Akt has been shown to prevent apoptotic death of a variety of cell types induced by a number of stimuli, including DNA damage, withdrawal of growth factors, and loss of cell adhesion (22). PhosphoAkt (Ser473) exerts its anti-apoptotic function in part by via phosphorylating BAD at serine 136 to its inactive form (22). BAD is an important negative regulator of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-xL (23, 24), which stabilizes the mitochondrial membrane and prevents the release of the pro-apoptotic cytochrome-C (25).

We first examined the expression of XIAP, pAkt (Ser473) and pBAD (Ser136) in RTECs isolated from hibernating 13-lined ground squirrel kidneys. Protection of ground squirrel RTECs from CS/REW induced apoptosis was associated with a significant increase in protein expression of pAkt (Ser473) and pBAD (Ser136), and persistence of XIAP protein expression. Mitochondrial separation determines the subcellular location of XIAP was cytosolic in both squirrel and mouse RTECs following CS/REW. The pattern of XIAP expression in cytosolic fractions mirrored that of whole cell lysates, thus confirming that XIAP expression is maintained in squirrel RTECs following CS/REW, whereas XIAP expression is significantly reduced in mouse RTECs following CS/REW.

To demonstrate that XIAP and phosphorylated Akt1 were required for protection from apoptosis, we used a gene silencing approach against XIAP and Akt1. Since gene silencing was not feasible in primary ground squirrel RTECs (due to shortage of primary cells) we used immortalized ground squirrel RTECS. As noted earlier, protection from apoptosis and cell death occurred to the same degree in primary ground squirrel RTECs and was therefore independent of immortalization. Ground squirrel RTECs silenced for the expression of XIAP or Akt1 had increased protein expression of cleaved caspase-3 and a significant increase in apoptotic cells versus untreated ground squirrel RTECs under conditions of CS/REW. Protection from apoptosis would provide a significant survival advantage to ground squirrels during winter, since hibernation engenders several distinct pro-apoptotic conditions such as hypothermia (4, 5), prolonged fasting (3), and hypothermia followed by rewarming and reperfusion of splanchnic organs (3, 6, 7, 26).

It may be possible to identify other potential therapeutic targets to prevent injury during CS/REW from the study of hibernating mammals. We have previously examined the kidney proteome during the torpor-arousal cycle of 13-lined ground squirrels (19), and identified a group of proteins that were increased during summer and arousal, involving hexose metabolism and ketone body synthesis. It is noteworthy that the latter enzymes may be anti-apoptotic, and suggest that specific responses to protect cells from pro-apoptotic ischemic stress during hibernation may exist. Hexokinase has been shown to stabilize the outer mitochondrial membrane and thus prevent the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis (27) (28, 29). Ketone body formation during hibernation may increase the survival of ground squirrels during acute hypoxia (30) (1). Other potential therapeutic targets that may ameliorate apoptosis during CS/WR include Apoptosis Inducing Factor (AIF) which mediates caspase independent apoptosis mediated (31). Following translocation to the nucleus, AIF induces chromatin condensation and DNA degradation, leading to caspase independent apoptosis (32). To our knowledge, the role of AIF during CS/WR of tubular cells has not been explored. Examination of potentially protective pathways employed by hibernators to prevent apoptotic cell death during CS/WR may provide novel therapies to prevent cell death during organ storage and transplantation.

The applicability of our current study to organ preservation lies in the possibility of increasing XIAP or Akt expression in donor organs. To that end, we have recently demonstrated that up regulation of XIAP can be achieved using UCF-101, a novel compound that specifically inhibits the proteolytic activity of HtrA2 (Jain et al. Transplantation. In press). Treatment of mouse RTECs subjected to in vitro CS/REW, and whole mouse kidneys subjected to prolonged ex vivo cold preservation, results in significantly increased XIAP, and significantly decreased caspase-3 protein and activity, and apoptosis.

A specific limitation of our in vitro model is that it employs hypothermia alone as opposed to hypothermic ischemia. Indeed, oxygen was not evacuated from the cell culture media. We chose to use hypothermia alone in our model to mimic the conditions that exist during retrieval and storage of human donor kidneys prior to transplantation, where oxygen is not removed. However, one could argue that due to the enormous cell density of donor kidneys, a state of almost complete oxygen depletion exists in the interstitial spaces of donor kidneys immediately after retrieval and flushing. Whether squirrel tubular cells are similarly resistant to apoptosis during hypothermic ischemia remains to be determined.

In conclusion our findings demonstrate that XIAP, pAkt (Ser473) and pBAD (Ser136) expression protect ground squirrel RTECs during CS/REW against apoptosis. Interestingly, tubular cell apoptosis is observed in human kidneys subjected to prolonged CS/REW during transplantation (4, 5). Our studies have implications regarding how isolated ground squirrel RTECs are protected from apoptosis during prolonged hypothermia and rewarming. Upregulation of XIAP, pAkt (Ser473) and pBAD (Ser136) may improve outcomes in donor kidneys with prolonged cold ischemia times that are subjected to rewarming and reperfusion during transplantation. By studying tolerance of profound hypothermia followed by rewarming in RTECs isolated from in hibernating ground squirrels, we have identified therapeutic targets that may lead to improved organ preservation, and novel therapies for delayed graft function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by 1 R03 DK96151-01 to Alkesh Jani. Charles Edelstein was supported by a VA Merit Award (1I01BX001737).

ABBREVIATIONS

- CS/REW

Cold Storage followed by Rewarming

- IBA

InterBout Arousal

- RTECs

Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells

- UW solution

University of Wisconsin solution

- XIAP

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Carey HV, Andrews MT, Martin SL. Mammalian hibernation: cellular and molecular responses to depressed metabolism and low temperature. Physiol Rev. 2003;83 (4):1153. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai D, McCarron RM, Yu EZ, Li Y, Hallenbeck J. Akt phosphorylation and kinase activity are down-regulated during hibernation in the 13-lined ground squirrel. Brain Res. 2004;1014 (1–2):14. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleck CC, Carey HV. Modulation of apoptotic pathways in intestinal mucosa during hibernation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289 (2):R586. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00100.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castaneda MP, Swiatecka-Urban A, Mitsnefes MM, et al. Activation of mitochondrial apoptotic pathways in human renal allografts after ischemiareperfusion injury. Transplantation. 2003;76 (1):50. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000069835.95442.9F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oberbauer R, Rohrmoser M, Regele H, Muhlbacher F, Mayer G. Apoptosis of tubular epithelial cells in donor kidney biopsies predicts early renal allograft function. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10 (9):2006. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1092006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He Z, Lu L, Altmann C, et al. Interleukin-18 binding protein transgenic mice are protected against ischemic acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295 (5):F1414. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90288.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melnikov VY, Faubel S, Siegmund B, Lucia MS, Ljubanovic D, Edelstein CL. Neutrophil-independent mechanisms of caspase-1- and IL-18-mediated ischemic acute tubular necrosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2002;110 (8):1083. doi: 10.1172/JCI15623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silva P, Hallac R, Spokes K, Epstein FH. Relationship among gluconeogenesis, QO2, and Na+ transport in the perfused rat kidney. Am J Physiol. 1982;242 (5):F508. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1982.242.5.F508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brezis M, Rosen S, Silva P, Epstein FH. Renal ischemia: a new perspective. Kidney Int. 1984;26 (4):375. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke TJ, Malhotra D, Shapiro JI. Factors maintaining a pH gradient within the kidney: role of the vasculature architecture. Kidney Int. 1999;56 (5):1826. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jani A, Ljubanovic D, Faubel S, Kim J, Mischak R, Edelstein CL. Caspase inhibition prevents the increase in caspase-3, -2, -8 and -9 activity and apoptosis in the cold ischemic mouse kidney. Am J Transplant. 2004;4 (8):1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain S, Keys D, Nydam T, Plenter RJ, Edelstein CL, Jani A. Inhibition of autophagy increases apoptosis during re-warming after cold storage in renal tubular epithelial cells. Transpl Int. 2014 doi: 10.1111/tri.12465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jani A, Epperson E, Martin J, et al. Renal protection from prolonged cold ischemia and warm reperfusion in hibernating squirrels. Transplantation. 2011;92 (11):1215. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182366401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damgaard RB, Gyrd-Hansen M. Inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) proteins in regulation of inflammation and innate immunity. Discovery medicine. 2011;11 (58):221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoos BA, Naray-Fejes-Toth A, Carretero OA, Ito S, Fejes-Toth G. Characterization of a mouse cortical collecting duct cell line. Kidney Int. 1991;39 (6):1168. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strober W. Trypan blue exclusion test of cell viability. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2001 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.ima03bs21. Appendix 3: Appendix 3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zafar I, Ravichandran K, Belibi FA, Doctor RB, Edelstein CL. Sirolimus attenuates disease progression in an orthologous mouse model of human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2010;78 (8):754. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tao Y, Kim J, Faubel S, et al. Caspase inhibition reduces tubular apoptosis and proliferation and slows disease progression in polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102 (19):6954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408518102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jani A, Orlicky DJ, Karimpour-Fard A, et al. The changing kidney proteome provides evidence for dynamic metabolism and regional redistribution of plasma proteins during torpor-arousal cycles of hibernation. Physiol Genomics. 2012 doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00010.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crook NE, Clem RJ, Miller LK. An apoptosis-inhibiting baculovirus gene with a zinc finger-like motif. J Virol. 1993;67 (4):2168. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2168-2174.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klupsch K, Downward J. The protease inhibitor Ucf-101 induces cellular responses independently of its known target, HtrA2/Omi. Cell death and differentiation. 2006;13 (12):2157. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Datta SR, Dudek H, Tao X, et al. Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell. 1997;91 (2):231. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Springer JE, Azbill RD, Nottingham SA, Kennedy SE. Calcineurin-mediated BAD dephosphorylation activates the caspase-3 apoptotic cascade in traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2000;20 (19):7246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07246.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Won J, Kim DY, La M, Kim D, Meadows GG, Joe CO. Cleavage of 14-3-3 protein by caspase-3 facilitates bad interaction with Bcl-x(L) during apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278 (21):19347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gross A, McDonnell JM, Korsmeyer SJ. BCL-2 family members and the mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13 (15):1899. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bullard RW, Funkhouser GE. Estimated regional blood flow by rubidium 86 distribution during arousal from hibernation. Am J Physiol. 1962;203:266. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1962.203.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gogvadze V, Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B. Mitochondria in cancer cells: what is so special about them? Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18 (4):165. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Southworth R, Davey KA, Warley A, Garlick PB. A reevaluation of the roles of hexokinase I and II in the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292 (1):H378. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00664.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gall JM, Wong V, Pimental DR, et al. Hexokinase regulates Bax-mediated mitochondrial membrane injury following ischemic stress. Kidney Int. 2011;79 (11):1207. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Alecy LG, Lundy EF, Kluger MJ, Harker CT, LeMay DR, Shlafer M. Beta-hydroxybutyrate and response to hypoxia in the ground squirrel, Spermophilus tridecimlineatus. Comparative biochemistry and physiology B, Comparative biochemistry. 1990;96 (1):189. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(90)90361-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Broker LE, Kruyt FA, Giaccone G. Cell death independent of caspases: a review. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11 (9):3155. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu C, Wang X, Huang Z, et al. Apoptosis-inducing factor is a major contributor to neuronal loss induced by neonatal cerebral hypoxia-ischemia. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14 (4):775. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]