Abstract

Osteopontin is robustly upregulated following myocardial infarction (MI), which suggests that it has an important role in post-MI remodeling of the left ventricle (LV). Osteopontin deletion results in increased LV dilation and worsened cardiac function. Thus, osteopontin exerts protective effects post-MI, but the mechanisms have yet to be defined. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) regulate LV remodeling post-MI, and osteopontin is a known substrate for MMP-2, -3, -7, and -9, although the cleavage sites have not been mapped. Osteopontin-derived peptides can exert distinct biological functions that may depend on their cleavage sites. We mapped the MMP-9 cleavage sites via LC-MS/MS analysis using label-free and N-terminal labeling methods, and compared them with those of MMP-2, -3, and -7. Each MMP yielded a unique cleavage profile with few overlapping cleavage sites. Using synthetic peptides, we validated 3 sites for MMP-9 cleavage at amino acid positions 151–152, 193–194, and 195–196. Four peptides were synthesized based on the upstream- and downstream-generated fragments and were tested for biological activity in isolated cardiac fibroblasts. Two peptides increased cardiac fibroblast migration rates post-wounding (p < 0.05 compared with the negative control). Our study highlights the importance of osteopontin processing, and confirms that different cleavage sites generate osteopontin peptides with distinct biological functions.

Keywords: myocardial infarction, osteopontin, cleavage sites, matrix metalloproteinases, MMP-9, cardiac, fibroblasts, peptides, proteomics, mass spectrometry

Introduction

Despite improvements in pharmacological and interventional therapies, myocardial infarction (MI)-induced cardiac remodeling that progresses to heart failure remains a leading cause of death in the United States (Go et al. 2014). Several matricellular members of the cardiac extracellular matrix (ECM) family, such as osteopontin (OPN), thrombospondin, and tenascin-C, play important roles in pathophysiological remodeling of the heart (Schellings et al. 2004; Charest et al. 2006; Dobaczewski et al. 2010; Okamoto and Imanaka-Yoshida 2012). OPN, also known as secreted phosphoprotein-1, is a phosphorylated acidic glycoprotein with multi-molecular weight forms varying from 30 to 100 kDa, depending on post-translational modifications (Sodek et al. 2000).

OPN occurs both as a soluble secreted cytokine and an immobilized matricellular protein (Singh et al. 2010; Frangogiannis 2012; Wolak 2014). Under physiological conditions, OPN is expressed at low levels in the heart by multiple cell types, including myocytes, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells (Singh et al. 2010). During pathological conditions, OPN expression markedly increases in multiple species including mice, rats, dogs, pigs, and humans (Komatsubara et al. 2003; Kossmehl et al. 2005; Suezawa et al. 2005; Dobaczewski et al. 2006).

In a murine MI model of permanent occlusion, OPN mRNA expression in the infarcted region of the left ventricle (LV) at day 3 post-MI was ∼40-fold higher than the sham-operated controls (Trueblood et al. 2001). Such a robust increase in OPN expression in the heart suggests a role for OPN in LV remodeling post-MI. Trueblood and colleagues presented genetic evidence for the role of OPN in myocardial remodeling using OPN−/− mice. After MI, OPN−/− mice showed exacerbated LV dilation and reduced collagen deposition compared with the wild type (Trueblood et al. 2001). Furthermore, OPN−/− mice showed worsened LV function 14 days post-MI, as evidenced by enhanced LV end-diastolic and end-systolic diameters and decreased percent fractional shortening and ejection fraction compared with the wild type mice (Krishnamurthy et al. 2009). Thus, there are increasing amounts of data that suggest a protective role for OPN during LV remodeling post-MI.

Post-MI, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are major contributors to LV remodeling. MMP protein expression increases in all cases of MI, and all ECM proteins can be degraded by at least one MMP (Iyer et al. 2014). Within the MMP family, MMP-9 has been reported as a prognostic indicator of cardiac dysfunction in MI patients (Hou et al. 2013). Thus, MMP-9 has emerged as a strong candidate for therapeutical applications with direct effects on cardiac remodeling. In vitro, OPN has been shown to be a substrate for several MMPs, including MMP-9, and there is increasing evidence suggesting active biological roles for MMP-generated OPN protein fragments (Agnihotri et al. 2001; Gao et al. 2004; Dean and Overall 2007; Takafuji et al. 2007; Goncalves DaSilva et al. 2010). The goals of the present study were: (i) to identify the cleavage sites for MMP-9 on OPN and to compare this with other MMPs (e.g., -2, -3, and -7); and (ii) to test the biological function of MMP-9 generated OPN fragments on cardiac fibroblast wound healing.

Materials and methods

All reagents used were mass-spectrometry grade.

Identification of MMP cleavage sites using the label-free method

Mouse recombinant osteopontin protein (mrOPN, No. 441-OP (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA); accession number Q547B5, clone F630228I12) was incubated with active MMP-9 (Calbiochem, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA) or activated proMMP-2, -3, or -7 (all from R&D Systems) at a ratio of 3:1 (w/w) in 1× zymogram developing buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA). Pro-form MMPs were activated with 1 mmol/L p-aminophenylmercuric acetate (APMA). All reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h The mixture was dried in the SpeedVac and resuspended in 20 μL 1 mol/L urea– 50 mmol/L ammonium with 10 mmol/L Tris-(2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine (TCEP), followed by 30 min reduction at room temperature. Iodoacetamide (16 mmol/L) was added for alkylation during 30 min at room temperature, in the dark. Sequencing grade modified trypsin (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) was added at 1:30 (enzyme:protein) and the incubation continued at 37 °C for 18 h. The digests were cleaned using C18 ziptip (Millipore, Billerica, Mass.), followed by analysis using liquid chromatography – tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). mrOPN directly digested with trypsin was included as a control and underwent the same procedure.

Identification of MMP cleavage sites using N-terminal labeling

mrOPN incubated with (reaction) or without (control) active MMP was labeled, respectively, with succinic-d4-anhydride: C/D/N isotopes (Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) or succinic-d0-anhydride (Sigma). Briefly, after incubation with MMP, samples were dried by SpeedVac and resuspended in 2 mg/mL of the appropriate succinic anhydride in 50% dimethylformamide (DMF), 40% H2O, 10% pyridine. After 1 h incubation at room temperature, labeled samples (control, d0-labeled; reaction, d4-labeled) were mixed and dried. Samples were reduced, alkylated, and trypsin-digested as described above. The digests were cleaned using C18 ziptip (Millipore), followed by LC-MS/MS analysis.

In-vitro MMP-9 cleavage assay

To validate the cleavage sites identified, we synthesized 2 synthetic OPN-peptides, 15 amino acids long, that included the cleavage sites in the middle of their sequence (Table 1) (CPC Scientific, Sunnyvale, Calif). These peptides were incubated with active MMP-9 (Calbiochem) at a ratio of 20:1 (w/w) in 1× zymogram developing buffer (Bio-Rad). Two negative controls, without MMP-9 or without OPN-peptide, were included and the mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. C18 ziptip (Millipore) was used for desalting and the samples were analyzed by mass spectrometry.

Table 1.

List of synthetic OPN-fragments used for MMP-9 cleavage validation (first 2 peptides) and OPN-peptides tested for their biological effect on fibroblast proliferation and migration (last 4 peptides).

| Designation | Sequence | Cleavage site |

|---|---|---|

| GL fragment | Ac-NGRGDSLAYGLRSKSRSFQV-amide | 151–152 |

| LL fragment | Ac-SLDVIPVAQLLSMPSDQDNN-amide | 195–196 |

| OPN-peptide151 (GL upstream) | Ac-TVDVPNGRGDSLAYG-amide | 151–152 |

| OPN-peptide152 (GL downstream) | Ac-LRSKSRSFQVSDEQY-amide | 151–152 |

| OPN-peptide195 (LL upstream) | Ac-GESKESLDVIPVAQ L-amide | 195–196 |

| OPN-peptide196 (LL downstream) | Ac-LSMPSDQDNNGKGSH-amide | 195–196 |

Note: OPN, osteopontin; MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase 9.

LC-MS/MS analysis

Analyses were performed on a Q Exactive (ThermoFisher, Waltham, Mass.) fitted with a 15 cm × 75 μm C18 column (5 μm particles with 100 Å pore size). A nano-UHPLC at 300 nL/min with a linear acetonitrile gradient (A = 2% acetonitrile and 0.2% formic acid in water; B = 0.2% formic acid in 90% acetonitrile) was used. Top 12 data-dependent MS/MS with exclusion for 25 s was set. Samples were run with Higher-energy C-trap dissociation (HCD) fragmentation at normalized collision energy of 30 and isolation width of 2 m/z. A lock mass of the polysiloxane peak at 371.1012 was used to correct the mass in MS and MS/MS. Target values in MS were 1e6 ions at a resolution setting of 70 000 and in MS2 1e5 ions at a resolution setting of 17 500. For cleavage site identification a 60 min linear acetonitrile gradient (from 5%–45% B over 60 min) was used. For the peptide cleavage assays, a linear acetonitrile gradient (from 5%–45% B over 20 min) was used.

Using Proteome Discoverer (version 1.4; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Mass.), MS/MS spectra were searched with SEQUEST against the mouse RefSeq database (3 November 2013) containing 27186 sequences. For this database search, the precursor mass tolerance and fragment mass tolerance were set at 10 ppm and 0.02 Da, respectively. Semi-trypsin was specified for recombinant protein cleaved by MMPs, while no trypsin was used for synthetic peptides cleaved by MMPs. Carbamidomethylation (C) and oxidation (M) were set as dynamic modifications for protein cleavage products. Succinylation-d0 or d4 modification on N-terminal or lysine was set as dynamic modifications for succinic anhydride labeled samples. A decoy version of the RefSeq mouse database was used to estimate peptide and protein false discovery rates.

Silver staining

mrOPN was incubated with MMP-2, -3, -7, or -9 as described above, and separated by SDS–PAGE electrophoresis in a 4%–12% Bis–Tris gel (Bio-Rad). mrOPN without MMP was used as a negative control. Gels were removed from the cast and fixed in 10% acetic acid – 50% methanol for 45 min. Silver staining solution was prepared as follows: 0.6 g/4 mL (AgNO3–ddH2O) mixed with 21 mL–250 μL–1.4 mL (ddH20 – 30% NaOH – 11.8 mol/L NH3H20). After 15 min, stained gels were rinsed extensively with water developed for 2 to 15 min in developing buffer (ddH2O – 1% citric acid – 37% HCHO (100 mL – 0.5 mL – 50 μL)). Bands were visualized using the GE Image Quant LAS4000 luminescent image analyzer (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA).

Cardiac fibroblast isolation

The mouse hearts were washed in phosphate saline buffer (PBS) and the LV separated from the right ventricle. The LV was minced and digested in collagenase solution (collagenase type 2, 600 U/mL and DNase I, 60 U/mL in Hanks' buffered saline solution) for 45 min at 37 °C. Cell aggregates were mechanically dissociated by pipetting during incubation. Cell lysate was centrifuged at 10 062g for 5 min and cells resuspended in fibroblast medium (DMEM–F12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution). Cardiac fibroblasts were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and used at passage 3.

Proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was assessed by a colorimetric immunoassay, based on the measurement of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation during DNA synthesis (Roche, Branford, Connecticut, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were plated in 0.1% FBS medium (negative control), or stimulated with 0.5 or 5 μmol/L of the test OPN peptide in 0.1% FBS medium. We used 10% FBS medium as a positive control.

Wound healing assay

Cell migration was analyzed using electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS; Applied Biophysics, Troy, Ohio, USA). Cells were plated in an ECIS-wound 96-well plate (4.0 × 104 cells/mL, quadruplicates/condition). Cells were allowed to proliferate until stable impedance values were observed (∼48 h); at this point the instrument was paused and the plate removed. The fibroblast medium was removed and replaced with: (i) 0.1% FBS medium (negative control); (ii) 10% FBS medium (positive control); or (iii) 0.1% FBS medium + 0.5 or 5 μmol/L test OPN-peptide. The plate was placed back in the ECIS instrument and the cell monolayer wounded for 10 sec at 1200 μA and 40 000 Hz. After wounding, impedance values were recorded for 48 h. Four custom activity OPN derived peptides (CPC Scientific) were tested for cell migration (Table 1). These peptides were designed upstream and downstream of the cleavage sites 151/152 and 195/196.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, Calif.). Results are the mean ± SEM for (n) number of independent observations. Statistical significance was determined using 2-way ANOVA followed by Newman– Keuls multiple comparisons test. A value for p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

MMP-9 generated OPN-fragments

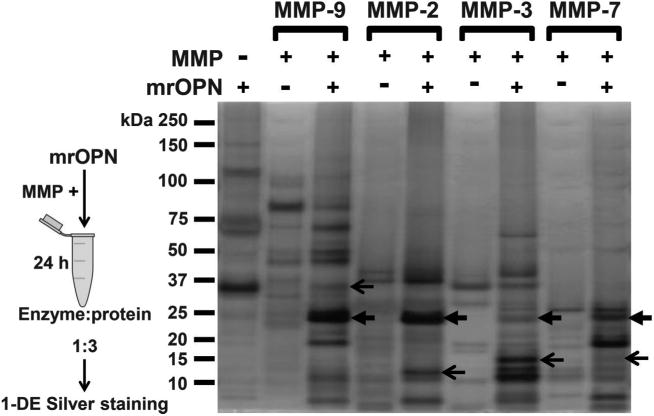

We used a mouse recombinant OPN protein that contains multiple post-translational modifications (PTMs) as observed in nature. As shown in Fig. 1, lane 1, under reducing conditions mrOPN shows 3 bands: 32.5 kDa, 65 kDa, and 130 kDa. Since PTMs may prevent OPN from proteolytic hydrolysis, the cleavage sites identified will correspond to OPN sites that can be cleaved by MMPs in its native condition. Figure 1 shows that OPN was cleaved by MMP-9 into multiple fragments. MMP-2, -3, and -7 all generated OPN-fragments. The generated fragments did not follow the same pattern for each MMP. Some fragments overlapped (such as some MMP-2 and MMP-9 sites), while others were distinct for each enzyme, suggesting the presence of both unique and overlapping cleavage sites. Fragments were compared after excluding the bands from the controls, full length OPN, and the respective MMP.

Fig. 1.

Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, -3, -7, and -9 induced distinct profiles of osteopontin fragments. Representative picture of a silver staining gel visualizing multiple fragments generated by each of MMP-2, -3, -7, and -9, by comparison with intact mouse recombinant osteopontin control (mrOPN). The generated fragments do not follow the same pattern, creating a unique cleavage profile for each enzyme. Some fragments do overlap between all or some MMPs (close arrows), whereas others were conserved for each enzyme (open arrows).

Identification of MMP-2, -3, -7, and -9 cleavage sites in osteopontin by LC-MS/MS

Although OPN cleavage by MMP-2, -3, -7, and -9 has been documented, the majority of cleavage sites have not been mapped (Agnihotri et al. 2001; Gao et al. 2004; Takafuji et al. 2007). Both label-free and N-terminal labeling methods were used to maximize identification of cleavage sites on OPN. With the label-free method, OPN was incubated with the particular MMP followed by trypsin digestion and LC-MS/MS analysis. OPN digested by trypsin only was used as a control. The non-tryptic ends of semi-tryptic peptides uniquely identified in MMP incubated samples were considered MMP cleavage sites. For N-terminal labeling method, OPN was incubated with or without MMP and labeled, respectively, with succinic d4- or d0-anhydride, to separate the MMP generated neo-N terminus sites from the trypsin generated ones. Labeled proteins were mixed and subjected to trypsin digestion and MS analysis.

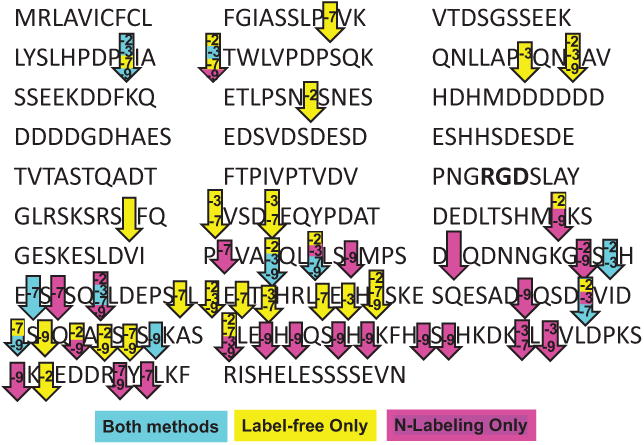

MMP-9 generated 30 cleavage sites, whereas 19 cleavage sites were identified for either MMP-2 or MMP-3, and 24 cleavage sites were identified for MMP-7. Seven OPN cleavage sites were identified as being in common among all 4 MMPs. Figure 2 shows the number of cleavage sites identified for each MMP by identification method. The OPN sequence with the identified cleavage sites for each MMP is presented in Fig. 3. Sites determined by both methods, which increased confidence rate, included 2 sites identified for MMP-2, 5 sites for MMP-3, 4 sites for MMP-7, and 5 sites for MMP-9 (Fig. 3, blue label). By the label-free method, 2 unique cleavage sites were identified for MMP-2 and MMP-3 and 4 unique sites for MMP-7 (Fig. 3, yellow label). The N-labeling method identified 3 unique cleavage sites for MMP-7 and 9 unique cleavage sites for MMP-9 (Fig. 3, pink label). Identified MMP cleavage sites are shown in Supplementary Table S12.

Fig. 2.

Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) cleavage sites on osteopontin (OPN) were identified using label-free and N-terminal labeling methods. The graph displays the number of cleavage sites identified by either label-free or N-labeling methods, by both methods, and using synthetic OPN-peptides (LL and GL fragments). Cleavage sites were identified using LC-MS/MS.

Fig. 3.

Visualization of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, -3, -7, and -9 relative cleavage sites on mouse recombinant osteopontin. Cleavage sites are identified with arrows. The MMP(s) responsible for cleavage is(are) identified by number, for example, -2 refers to MMP-2. Arrows are color coded depending on the identification method. Blue represents cleavage sites determined by both methods (label-free and N-labeling), yellow denotes sites identified only by the label-free method, and pink indicates cleavage sites determined by the N-labeling method only. Arrows with no label correspond to a site cleaved by all tested MMPs.

Using synthetic peptides to validate MMP-9-induced OPN cleavage sites

Our expertise with MMP-9-mediated cardiac remodeling motivated us to focus further attention on additional MMP-9 targeted OPN cleavage sites. Two peptides, 20 amino acids long, were selected to validate the cleavage sites identified in Fig. 3, based on the following rationale: (i) Gly–Leu (GL) at position 151–152, is one of the MMP-9 consensus cleavage motifs that was previously identified by unbiased phage display strategy, and is only 5 amino acids downstream of the RGD motif that facilitates OPN-cell interactions (McFarland et al. 1995; Kridel et al. 2001). GL was not identified as a cleavage site by either label-free or N-labeling methods. This peptide, referred to as the GL fragment, was synthesized for cleavage validation: 142NGRGDSLAYGLRSKSRSFQV; and (ii) Leu– Leu (LL) at position 195–196 was identified as a common cleavage site for all 4 MMPs: by both label-free and N-labeling methods for MMP-7 and -9 and by 1 of the 2 methods for MMP-2 and -3. For this cleavage site, the following peptide, referred to as the LL fragment, was synthesized for validation: 186SLDVIPVAQLLSMPSDQDNN.

Each peptide was incubated with MMP-9 at 20:1 ratio as described in the Materials and methods. The reaction fragments were compared with both negative controls (without MMP-9 and MMP-9 only without protein). As seen in Fig. 4, the peak of both intact peptides was significantly reduced after incubation with MMP-9 with a hydrolytic efficiency of 99% for the GL fragment and 93% for the LL fragment as calculated using peak area. Of note, in addition to the LL site, there was also cleavage at the AQ site of this peptide (Fig. 4A). Both AQ and LL sites of the LL fragment were cleaved and validated. Interestingly, the GL fragment was cleaved at the GL site despite the absence of detection by label-free and N-labeling methods when using the full-length protein (Fig. 4B). One explanation for this difference is that the native tertiary structured protein could limit MMP-9 accessibility, whereas the linear short amino acid sequence is more readily cleaved. This indicates that absence of in-vitro cleavage does not rule out the possibility that the site can be cleaved.

Fig. 4.

Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 cleavage sites were validated using synthetic osteopontin (OPN)-peptides. Figure shows MS/MS results for MMP-9 cleavage site validation using synthetic peptides. (A) Fragment LL: The upper panel shows the synthetic Fragment LL identified at 35.18 min retention time. The middle panel shows the MMP-9-generated fragments with their retention time. Results show cleavage at 2 sites (AQ and LL; position 193-194 and 195-196 respectively). The lower panel is the MMP-9 only background. Peptide cleavage efficiency was ∼93% (n = 5 technical replicates) and was calculated using peak area. (B) Fragment GL: Upper panel shows synthetic peptide identified at 20.38 min retention time. Middle panel shows the MMP-9 generated fragments, with cleavage between GL (position 151–152), with their retention times. Lower panel is the MMP-9 only background. The peptide cleavage efficiency was ∼99% (n = 5 technical replicates) and was calculated using peak area.

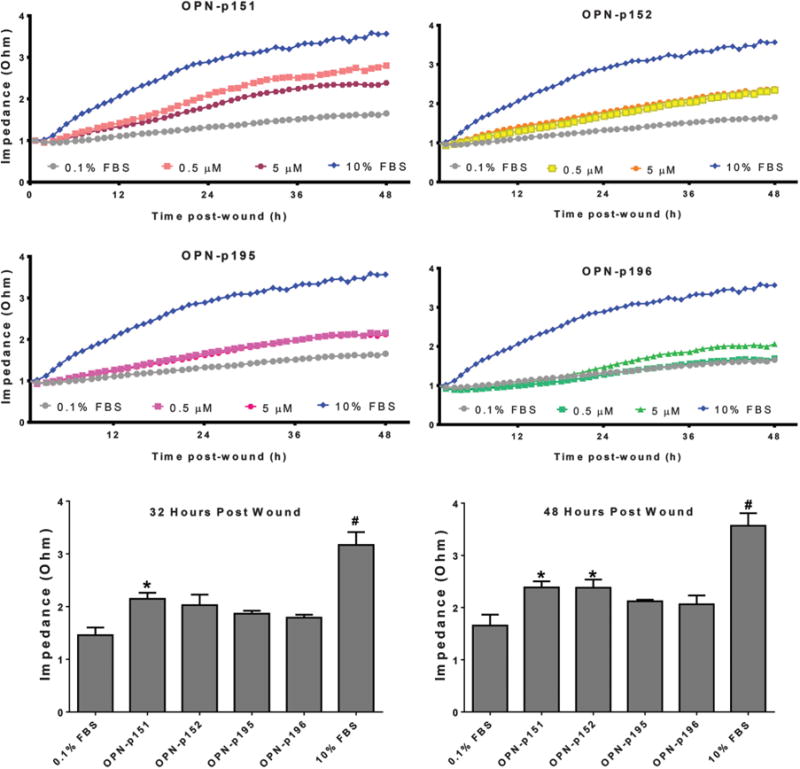

Biological function of synthesized OPN-peptides based on MMP-9 cleavage sites

Based on the GL and LL MMP-9 cleavage site validations, a total of 4 peptides 15-amino acids long (OPN-peptide) upstream and downstream of GL and LL cleavage sites were synthesized as shown in Table 1. The biological activity of these peptides was tested to assess the physiological importance of the cleavage and determine whether the fragments possess any functional domains. All 4 peptides were used to assess the impact on murine cardiac fibroblast proliferation and wound healing. None of the peptides affected cardiac fibroblast proliferation (Supplementary Fig. S12). As shown in Fig. 5, peptide OPN-151 (GL upstream) significantly increased wound healing rates after 32 h and this effect was present up to 48 h; OPN-p152 (GL downstream) only showed effects 48 h after wounding, and OPN-p195 (LL upstream) and OPN-p196 (LL downstream) had no effect on fibroblast wound healing. Because the wound healing response is dependent on both proliferation and migration, the lack of a proliferation response indicates that the peptides are functioning to alter migration.

Fig. 5.

Osteopontin (OPN)-derived synthetic peptides stimulated wound healing rates in cardiac fibroblasts. Four peptides 15-amino acids long (OPN-p151, -p152, -p195, and -p196) were synthesized based on the MMP-9 cleavage sites GL (151/152) and LL (195/196). Each peptide was designed upstream (p151 and p195) or downstream (p152 and p196) of the cleavage site, as shown on Table 1. Each OPN peptide was tested at 2 concentrations of 0.5 and 5.0 μmol/L, for biological effects on wounded isolated cardiac fibroblast (top and middle panels). Ten percent fetal bovine serum (FBS) was used as the positive control and 0.1% FBS was the negative control. Fibroblasts were cultured until confluent, then wounded and treated with or without peptide. The wound closing rates were recorded using electric cell-substrate impedance sensing. Wound healing was observed up to 48 h post-wounding. No significant effect was observed with any peptide during the first 24 h post-wounding OPN-p151 significantly increased wound healing 32 h post-wound, and this effect was maintained up to 48 h. OPN-p152 enhanced wound healing at 48 h post-wounding. The lower panel shows bar graphs for all OPN-peptides at concentrations of 5 μmol/L at 32 and 48 h post-wounding Both OPN-p195 and OPN-p196 had no effect on fibroblast healing rates. Data are the mean ± SEM, n = 4 biological replicates/group. Analysis was by 2-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test; *, p < 0.05 compared with the 0.1% treatment group; #, p < 0.05 by comparison with all of the other groups.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to determine where MMP-9 cleaved OPN and to determine whether the generated cleavage peptides had biological activity. The major findings were that (i) MMP-9 proteolytically processed OPN in at least 30 sites, and (ii) the generation of peptides from the GL, but not the LL, cleavage site, resulted in increased cardiac fibroblast migration. Combined, these results indicate that cleavage site affects the biological activity of the generated OPN-fragments and OPN-peptides may have therapeutic potential in the post-MI setting.

Cellular interactions involving OPN are mostly mediated by integrin receptors, which by binding to the different domains of OPN can regulate cellular differentiation, migration, adhesion, and apoptosis (Grassinger et al. 2009). OPN contains an Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) amino acid sequence that facilitates OPN-cell interactions via the αvβ3 integrin that promotes cell adhesion (McFarland et al. 1995). Proteolytic cleavage can either enhance or reduce the ability of OPN to bind to integrins (Christensen and Sorensen 2014). This illustrates that slight differences in the cleavage pattern, i.e., different cleavage sites, can have substantial effects on the biological function of OPN.

OPN is a biological substrate for MMPs, thrombin, plasmin, and cathepsin D (Christensen et al. 2010; Christensen and Sorensen 2014). Of these proteases, MMPs are robustly expressed post-MI and play a major role in LV remodeling (Iyer et al. 2014). Accordingly, we focused our efforts on OPN cleavage by MMPs, particularly MMP-2, -3, -7, and -9 that have been reported to interact with or cleave near the RGD motif (Brooks et al. 1996; Agnihotri et al. 2001; Hamano et al. 2003).

OPN cleavage by MMP-2, -3, -7, and -9 in other organs has been reported (Agnihotri et al. 2001; Gao et al. 2004; Takafuji et al. 2007), but mapping of cleavage sites using mass spectrometry label-free and N-labeling methods has not been done. Studies have highlighted the biological activity of some MMP-generated OPN fragments in cancer (Takafuji et al. 2007), but to the best of our knowledge, none of these fragments have been tested in the context of heart disease or on cardiac fibroblasts. Additionally, none of those fragments overlap with the ones tested in our study.

Our study identifies novel cleavage sites in OPN by multiple MMPs and identifies specific OPN-peptides by which OPN might mediate its biological actions post-MI. We found that mrOPN protein is cleaved by MMP-2, -3, -7, and -9, generating both unique and overlapping fragments for all 4 MMPs. These results highlight the unique cleavage profile for each enzyme. Using label-free and N-labeling methods, a total of 24 and 30 cleavage sites were identified for MMP-7 and MMP-9, respectively, and 19 cleavage sites for both MMP-2 and MMP-3 (Figs. 2 and 3). Of the cleavage sites identified, 2 sites for MMP-2, 9 sites for MMP-9, and 5 sites for MMP-3 and MMP-7 were considered high confidence, since they were identified by both label-free and N-labeling methods or by validation using cleavage site generated fragments. Additionally, 7 sites overlapped among all 4 MMPs (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 12). Using a synthetic peptide, an MMP-9 consensus cleavage site motif at position 151–152 was cleaved by MMP-9, although it was not recognized by label-free nor N-labeling method. This probably results from the native tertiary structure blocking MMP-9 from interacting with the site, which would not occur when using a short linear peptide. High confidence cleavage sites by MMP-9 at position 193–194 and 195–196 were also validated.

Finally, 4 synthesized peptides, each 15 amino acids long, based on the upstream and downstream sequence at positions 151–152 and 195–196 were tested for biological activity under serum-deprived conditions. Two of the 4 tested peptides increased fibro-blast wound-healing rates at32 to 48 h post-wounding, which may be relevant in vivo in the infarct environment. Since these pep-tides did not affect cell proliferation, the effects observed in the wound healing assay result from cell migration. OPN-p151 (GL upstream) showed the quickest and more prolonged effect and contains the RGD motif within its sequence. Other groups have used short RGD-based peptides to study fibroblast migration. Munevar and colleagues used the peptide GRGDTP to disrupt cell-substrate attachment in traction force microscopy studies (Munevar et al. 2001). Peptides containing the RGD motif act as competitive inhibitors of integrin–ECM binding. Therefore, OPN-p151 may enhance fibroblast migration by disrupting cell-substrate attachment. OPN-p152 (GL downstream) displayed later term effects, with fibroblasts showing increased migration rates after 48 h, suggesting that the peptide contains one or more functional domains that exert biological functions. Our results suggest that peptides generated from the same cleavage site can have different kinetics. Of note, OPN-p151 and OPN-p152 peptides frame the amino acid position 151–152, which was not identified as a cleavage site when using the full length protein. This suggests that position 151–152 can only be recognized by MMP-9 when OPN loses its tertiary structure; thus, in native conditions 151–152 is a secondary cleavage site, not a primary. Enhanced fibroblast migration rates are associated with upregulation of ECM protein synthesis and scar formation (Dobaczewski et al. 2010). Thus, identification of pro-migration cleavage sites may offer new cardio protective avenues in the setting of impaired cardiac healing.

Post-MI, OPN is exposed to a large number of different proteinases that may generate additional fragments. The large amount of proteins in the heart and number of proteinases makes it impossible to identify all cleavage fragments and cleavage sites of specific proteinases in the infarcted heart. Using in-vitro approaches to validate enzyme cleavage sites as well as identifying OPN functional domains is one step closer to better understand the biological role of OPN. Our approach could potentially lead to the development of functional therapeutic peptides to mimic the protective effects of OPN in cardiac remodeling post-MI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from HHSN 268201000036C (N01-HV-00244) for the San Antonio Cardiovascular Proteomics Center (R01HL075360, HL095852, HL051971, and P20GM104357), as well as from the Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service of the Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development Award to M.L.L. We acknowledge support from the American Heart Association 14POST18770012 to R.P.I. and 14SDG18860050 to L.E.C.B. Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest associated with this work.

Footnotes

This article is part of a special issue entitled “2nd Cardiovascular Forum for Promoting Centers of Excellence and Young Investigators.”

Contributor Information

Merry L. Lindsey, San Antonio Cardiovascular Proteomics Center; Mississippi Center for Heart Research, Department of Physiology and Biophysics, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216-4505, USA; Research Service, G.V. (Sonny) Montgomery Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Jackson, Mississippi, USA

Fouad A. Zouein, San Antonio Cardiovascular Proteomics Center; Mississippi Center for Heart Research, Department of Physiology and Biophysics, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216-4505, USA

Yuan Tian, San Antonio Cardiovascular Proteomics Center; Mississippi Center for Heart Research, Department of Physiology and Biophysics, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216-4505, USA.

Rugmani Padmanabhan Iyer, San Antonio Cardiovascular Proteomics Center; Mississippi Center for Heart Research, Department of Physiology and Biophysics, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216-4505, USA.

Lisandra E. de Castro Brás, San Antonio Cardiovascular Proteomics Center; East Carolina University, Department of Physiology, Greenville, North Carolina, USA

References

- Agnihotri R, Crawford HC, Haro H, Matrisian LM, Havrda MC, Liaw L. Osteopontin, a novel substrate for matrix metalloproteinase-3 (stromelysin-1) and matrix metalloproteinase-7 (matrilysin) J Biol Chem. 2001;276(30):28261–28267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103608200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks PC, Stromblad S, Sanders LC, von Schalscha TL, Aimes RT, Stetler-Stevenson WG, et al. Localization of matrix metalloproteinase MMP-2 to the surface of invasive cells by interaction with integrin alpha v beta 3. Cell. 1996;85(5):683–693. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charest A, Pepin A, Shetty R, Cote C, Voisine P, Dagenais F, et al. Distribution of SPARC during neovascularisation of degenerative aortic stenosis. Heart. 2006;92(12):1844–1849. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.086595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen B, Sorensen ES. Osteopontin is highly susceptible to cleavage in bovine milk and the proteolytic fragments bind the alphaVbeta(3)-integrin receptor. J Dairy Sci. 2014;97(1):136–146. doi: 10.3168/jds.2013-7223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen B, Schack L, Klaning E, Sorensen ES. Osteopontin is cleaved at multiple sites close to its integrin-binding motifs in milk and is a novel substrate for plasmin and cathepsin D. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(11):7929–7937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.075010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean RA, Overall CM. Proteomics discovery of metalloproteinase substrates in the cellular context by iTRAQ labeling reveals a diverse MMP-2 substrate degradome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6(4):611–623. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600341-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobaczewski M, Bujak M, Zymek P, Ren G, Entman ML, Frangogiannis NG. Extracellular matrix remodeling in canine and mouse myocardial infarcts. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;324(3):475–488. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobaczewski M, Gonzalez-Quesada C, Frangogiannis NG. The extracellular matrix as a modulator of the inflammatory and reparative response following myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48(3):504–511. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frangogiannis NG. Matricellular proteins in cardiac adaptation and disease. Physiol Rev. 2012;92(2):635–688. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao YA, Agnihotri R, Vary CP, Liaw L. Expression and characterization of recombinant osteopontin peptides representing matrix metallo-proteinase proteolytic fragments. Matrix Biol. 2004;23(7):457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, et al. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics–2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(3):399–410. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000442015.53336.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves DaSilva A, Liaw L, Yong VW. Cleavage of osteopontin by matrix metalloproteinase-12 modulates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis disease in C57BL/6 mice. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(3):1448–1458. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassinger J, Haylock DN, Storan MJ, Haines GO, Williams B, Whitty GA, et al. Thrombin-cleaved osteopontin regulates hemopoietic stem and progenitor cell functions through interactions with alpha9beta1 and alpha4beta1 integrins. Blood. 2009;114(1):49–59. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-197988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamano Y, Zeisberg M, Sugimoto H, Lively JC, Maeshima Y, Yang C, et al. Physiological levels of tumstatin, a fragment of collagen IV alpha3 chain, are generated by MMP-9 proteolysis and suppress angiogenesis via alphaV beta3 integrin. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(6):589–601. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00133-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou ZH, Lu B, Gao Y, Cao HL, Yu FF, Jing N, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and myeloperoxidase (MPO) levels in patients with nonobstructive coronary artery disease detected by coronary computed tomographic angiography. Acad Radiol. 2013;20(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer RP, de Castro Bras LE, Jin YF, Lindsey ML. Translating Koch's postulates to identify matrix metalloproteinase roles in postmyocardial infarction remodeling: cardiac metalloproteinase actions (CarMA) postulates. Circ Res. 2014;114(5):860–871. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.301673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsubara I, Murakami T, Kusachi S, Nakamura K, Hirohata S, Hayashi J, et al. Spatially and temporally different expression of os-teonectin and osteopontin in the infarct zone of experimentally induced myocardial infarction in rats. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2003;12(4):186–194. doi: 10.1016/S1054-8807(03)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossmehl P, Schonberger J, Shakibaei M, Faramarzi S, Kurth E, Habighorst B, et al. Increase of fibronectin and osteopontin in porcine hearts following ischemia and reperfusion. J Mol Med (Berl) 2005;83(8):626–637. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kridel SJ, Chen E, Kotra LP, Howard EW, Mobashery S, Smith JW. Substrate hydrolysis by matrix metalloproteinase-9. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(23):20572–20578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100900200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy P, Peterson JT, Subramanian V, Singh M, Singh K. Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases improves left ventricular function in mice lacking osteopontin after myocardial infarction. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;322(1–2):53–62. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9939-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland RJ, Garza S, Butler WT, Hook M. The mutagenesis of the RGD sequence of recombinant osteopontin causes it to lose its cell adhesion ability. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1995;760:327–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munevar S, Wang YL, Dembo M. Distinct roles of frontal and rear cell-substrate adhesions in fibroblast migration. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12(12):3947–3954. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.12.3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto H, Imanaka-Yoshida K. Matricellular proteins: new molecular targets to prevent heart failure. Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;30(4):e198–e209. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2011.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellings MW, Pinto YM, Heymans S. Matricellular proteins in the heart: possible role during stress and remodeling. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;64(1):24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Foster CR, Dalal S, Singh K. Osteopontin: role in extracellular matrix deposition and myocardial remodeling post-MI. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48(3):538–543. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodek J, Ganss B, McKee MD. Osteopontin. Criti Rev Oral Biol Med. 2000;11(3):279–303. doi: 10.1177/10454411000110030101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suezawa C, Kusachi S, Murakami T, Toeda K, Hirohata S, Nakamura K, et al. Time-dependent changes in plasma osteopontin levels in patients with anterior-wall acute myocardial infarction after successful reperfusion: correlation with left-ventricular volume and function. J Lab Clin Med. 2005;145(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takafuji V, Forgues M, Unsworth E, Goldsmith P, Wang XW. An osteopontin fragment is essential for tumor cell invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2007;26(44):6361–6371. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trueblood NA, Xie Z, Communal C, Sam F, Ngoy S, Liaw L, et al. Exaggerated left ventricular dilation and reduced collagen deposition after myocardial infarction in mice lacking osteopontin. Circ Res. 2001;88(10):1080–1087. doi: 10.1161/hh1001.090842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolak T. Osteopontin — a multi-modal marker and mediator in atherosclerotic vascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2014;236(2):327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.