Abstract

Members of the genus Geobacillus have been isolated from a wide variety of habitats worldwide and are the subject for targeted enzyme utilization in various industrial applications. Here we report the isolation and complete genome sequence of the thermophilic starch-degrading Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1. The strain 12AMOR1 was isolated from deep-sea hot sediment at the Jan Mayen hydrothermal Vent Site. Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 consists of a 3,410,035 bp circular chromosome and a 32,689 bp plasmid with a G + C content of 52 % and 47 %, respectively. The genome comprises 3323 protein-coding genes, 88 tRNA species and 10 rRNA operons. The isolate grows on a suite of sugars, complex polysaccharides and proteinous carbon sources. Accordingly, a versatility of genes encoding carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZy) and peptidases were identified in the genome. Expression, purification and characterization of an enzyme of the glycoside hydrolase family 13 revealed a starch-degrading capacity and high thermal stability with a melting temperature of 76.4 °C. Altogether, the data obtained point to a new isolate from a marine hydrothermal vent with a large bioprospecting potential.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s40793-016-0137-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Thermophile, Geobacillus, Enzymes, Bioprospecting

Introduction

In 2001 the genus Geobacillus was proposed by Nazina et al. [1] to distinguish it from the genus Bacillus. Bacteria of the genus Geobacillus have been isolated from diverse marine and terrestrial habitats such as oil wells [2], cool soils like from Bolivian Andes [3], sediments from Mariana Trench [4] and deep sea hydrothermal vents [5]. Surprisingly, these thermophiles can be isolated from cold environments from different geographical regions in such large quantities that it speaks against a “contamination” from hot environments, which have been described as paradox [6]. The influence of direct heating action of the sun upon the upper soil layers and heat development due to putrefactive and fermentative processes of mesophiles could give an explanation for their abundance [7, 8]. To our knowledge, Geobacillus has not been isolated from an Arctic marine habitat. As of June 2015, 37 Geobacillus genomes have been deposited in GenBank. Due to the development of next generation sequencing the number of new sequenced genomes (17) has been almost doubled in the last one and a half years. Of all Geobacillus genomes, 13 have been described as complete, whilst the other 24 genomes have been deposited as drafts. The genus exhibits a broad repertoire of hydrolytic and modifying enzymes and is therefore a valuable resource for biocatalysts involved in biotechnological processes with accelerated temperatures [9, 10]. The application of thermophilic microorganisms or enzymes in biotechnology gives advantage in enhancing biomass conversion in a variety of biotechnical applications; it minimizes contamination and can reduce the process costs [11]. Diverse Geobacillus strains comprise an arsenal of complex polysaccharide degrading enzymes such as for lignocellulose [12]. Other Geobacillus strains are able to degrade a broad range of alkanes [13, 14]. Up to now a multiplicity of patents derived from the genus comprises restriction nucleases, DNA polymerases, α-amylases, xylanase, catalase, lipases and neutral protease among others (EP 2392651, US2011020897, EP2623591, US2012309063, KR100807275 [15, 16]). The glycoside hydrolase group 13 (GH13) α-amylases are well studied enzymes which have a broad biotechnological application, for example for bioethanol production, food processing or in textile and paper industry [17]. Due to the broad application of α-amylases there is a focus of interest to identify novel α-amylases for new and improved applications in biotechnology. In addition to functional screening for enzyme activity, genome investigation is a valuable tool to identify potential biocatalysts. Here we present the isolation and metabolic features of Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 (DSM 100439) together with the description of the complete genome and its annotation.

Organism information

Classification and features

Geobacillus sp. strain 12AMOR1 was isolated from a 90°C hot deep-sea sediment sample collected in July of 2012 from the Arctic Jan Mayen Vent Field (JMVF). The sample was collected using a shovel box connected to a Remote Operating Vehicle (ROV) at a water depth of 470 m. The detailed description of the JMVF site is described elsewhere [18, 19].

The bacterium was isolated at 60°C on Archaeoglobus medium agar plates [20] pH 6.3 containing 1 % Starch (Sigma Aldrich) at the attempt to screen for starch degraders. Genomic DNA of isolates was extracted using FastDNA® Spin Kit for Soil (MP). The partial 16S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR using Hot Star Plus (QIAGEN) and following universal primers B8f (5’ AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG) [21] and Un1391r (5’ GACGGGCGGTGWGTRCA) [22]. The preliminary partial 16S rRNA gene fragment of strain 12AMOR1 has been analyzed using the megablast algorithm in the standalone blastn [23] against 16S ribosomal RNA (Bacteria and Archaea database). The partial 16S rRNA gene shared 98 % sequence identity with the strains G. stearothermophilusDSM 22T (NR_114762.1) and R-35646 (NR_116987.1), as well as to other Geobacillus species: Geobacillus subterraneus strain 34T (NR_025109.1), Geobacilluszalihae strain NBRC 101842T (NR_114014.1), Geobacillus thermoleovorans strain BGSC 96A1T (ref|NR_115286.1), Geobacillus thermocatenulatus strain BGSC 93A1T (NR_043020.1), Geobacillus vulcani strain 3S-1T (NR_025426.1) and Geobacillus kaustophilus strain BGSC 90A1T (NR_115285.1) (Additional file 1). The genome of Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 encoded 10 genes for 16S rRNA whereby blastn analysis [23] revealed small differences in top hits towards multiple Geobacillus strains. The 16S rRNA gene GARCT_01776 was identical to the partial sequence obtained by PCR mentioned above, and thus, the whole 16S rRNA gene GARCT_01776 was used for the phylogenetic analysis.

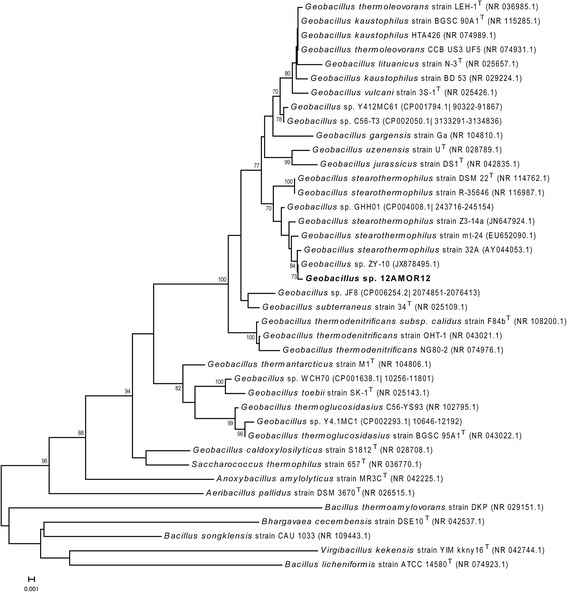

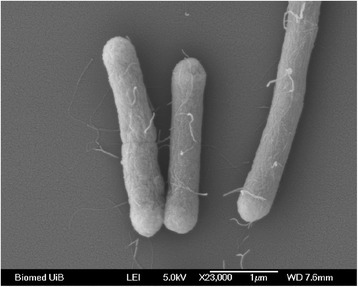

A phylogenetic tree was constructed from aligning the 16S rRNA gene GARCT_01776 with 16S rRNA genes from selected strains and species from the same genus using MUSCLE [24, 25] and Neighbor-Joining algorithm incorporated in MEGA 6.06 [26]. The 16S rRNA from Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 grouped together with Geobacillus sp. ZY-10 and G. stearothermophilus strain 32A, Z3-14a and mt-24 (Fig. 1). Interestingly, within the sub-cluster of G. stearothermophilus, the isolate 12AMOR1 and herein before mentioned strains were grouped apart from the type strain G. stearothermophilusDSM 22T. To further evaluate how closely related the new isolate was to existing species of Geobacillus, a digital DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) [27] was performed using the complete genomes of 13 Geobacillus species listed in Additional file 2. DDH estimations below 70 % suggested that Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 belonged to a new species. The level of relatedness by DDH estimations using formula 2 (identities/HSP length) ranged from 21.5 to 41.5 % between the isolate and different Geobacillus species. Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 is a Gram-positive [28], spore-forming, motile, facultative anaerobic rod. The cells are in average 0.5–0.7 μm in width and between 1.8 and 4.5 μm long. In addition, cells forming long filamentous chains were observed by microscopy. The cells were peritrichous flagellated (Fig. 2) consistent with previously observation of Geobacilli [1, 29]. Terminal ellipse shaped spores was observed.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree showing the position of Geobacillus strain 12AMOR1 relative to the other strains of Geobacillus based on 16S rRNA. The Neighbor-Joining tree was built from 1374 aligned positions of the 16S rRNA gene sequences and derived based on the Tamura 3-parameter as preferred model and gamma distribution (shape parameter = 1) for modeling rates variation among sites using MEGA6. Bootstrap values above 70, expressed as percentage of 1000 replicates, are shown at branch points. Bar: 0.01 substitutions per nucleotide position. Bacillus songklensis strain CAU 1033 (NR_109443.1), Bhargavaea cecembensis strain DSE10 (NR_042537.1), Bacillus licheniformis strain ATCC 14580T (NR_074923.1), Virgibacillus kekensis strain YIM kkny16T (NR_042744.1) and Bacillus thermoamylovorans strain DKP (NR_029151.1) was used as outgroup

Fig. 2.

Scanning electron microscopy of Geobacillus sp. strain 12AMOR1

The isolate was able to grow in a temperature range of 40 to 70 °C and pH of 5.5 to 9.0, with a temperature optimum of 60 °C and a broad pH optimum between 6.5 and 8.0. Growth was observed in concentrations ranging between 0 and 5 % NaCl. Besides aerobic growth, Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 was able to grow on yeast extract in anaerobic NRB medium containing nitrate [30].

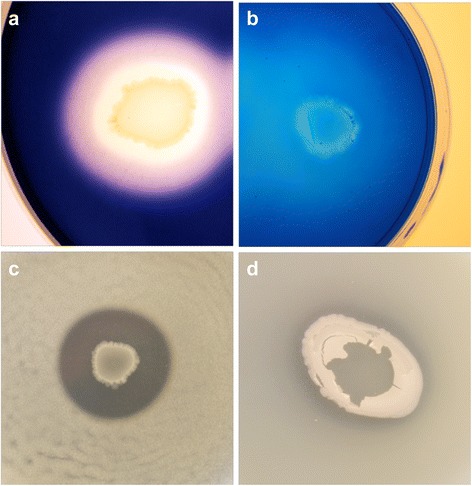

Besides the utilization of starch, Geobacillus 12AMOR1 was able to grow on complex polysaccharides such as xylan, chitin and α-cellulose (Table 1). Fast growth was accomplished by cultivating the isolate on yeast extract and gelatin. In addition, the isolate utilizes lactose, galactose and organic acids such as lactate and acetate. No growth was observed using pectine, xylose, tween20 and tween80 as carbon source. Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 degrades DNA supplemented in agar (Fig. 4d).

Table 1.

Classification and general feature of Geobacillus sp. strain 12AMOR1 according to the MIGS recommendations

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [55] | |

| Phylum Firmicutes | TAS [56, 57] | ||

| Class Bacilli | TAS [58, 59] | ||

| Order Bacillales | TAS [60, 61] | ||

| Family Bacillaceae | TAS [61, 62] | ||

| Genus Geobacillus | TAS [1, 7, 29] | ||

| Species Geobacillus sp. | IDA | ||

| Strain 12AMOR1 | IDA | ||

| Gram stain | Positive | IDA | |

| Cell shape | Rod | IDA | |

| Motility | Motile | IDA | |

| Sporulation | Spore forming | IDA | |

| Temperature range | 40-70 °C | IDA | |

| Optimum Temperature | 60 °C | IDA | |

| pH range, optimum | 5.5–9.0; 6.5–8.0 | IDA | |

| Carbon sources | starch, yeast extract, lactose, galactose, fructose, lactate, acetate, dextrin | IDA | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Marine, hydrothermal sediment | IDA |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | 0–5 % | IDA |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Aerobic | IDA |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free-living | IDA |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Non-pathogen | NAS |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Troll Wall vent, Arctic Mid-Ocean ridge | IDA |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection | July 2012 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | 71.29665 N | IDA |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | 5.773133 W | IDA |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | 470m | IDA |

Evidence codes – IDA Inferred from Direct Assay, TAS Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature), NAS Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [63]

Fig. 4.

Functional activity screening. Degradation halos around colonies of Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 growing on agar plates supplemented with a, starch; b, gelatin; c, skim milk and d, DNA

The strain produced acid, however no gas production was observed from the following carbohydrate substrates using API 50CH stripes and CHB/E medium (BioMérieux, France): D-fructose, glycerol, esculin, D-maltose, D-saccharose, D-trehalose, D-melezitose, amidon (starch), D-turanose, methyl-αD-glucopyranoside and potassium 5-ketogluconate. Weak acid was produced from D-glucose, D-mannose, methyl-αD-mannopyranoside, N-acetyl-glucosamine, D-lactose, D-melibiose, inulin, D-raffinose, glycogen, xylitol, (gentiobiose), D-lyxose and D-tagatose. In the API Zym panel (BioMérieux, France), strong activity was determined for alkaline phosphatase, esterase (C4), esterase/lipase (C8), leucine arylamidase, α-chymotrypsin, acidic phosphatase and α-glucosidase. Weak activity was observed for lipase (C14), valine arylamidase, cysteine arylamidase, naphtol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase, β-glucuronidase and β-glucosidase.

Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 was catalase positive using 3 % hydrogen peroxide. Tests using diatabs (Rosco Diagnostics) identified the isolate as oxidase positive and urease negative.

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

The complete genome sequence and annotation data of Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 have been deposited in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession number CP011832.1. Sequencing was performed at the Norwegian Sequencing Centre in Oslo, Norway [31]. Assembly and finishing steps were performed at the Centre for Geobiology, University of Bergen, Norway. Annotation was performed using the Prokka automatic annotation tool [32] and manually edited to fulfill NCBI standards. Table 2 summarizes the project information and its association with MIGS version 2.0 compliance [33].

Table 2.

Genome sequencing information

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Pacific Biosciences 10 kb library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platform | PacBio |

| MIGS-31.1 | Fold coverage | 88x |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Hierarchical Genome Assembly Process (HGAP) v2 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal |

| Locus tag | GARCT, pGARCT | |

| Genebank ID | Chromosme CP011832 | |

| Plasmid CP011833 | ||

| Genebank date of release | June 15, 2015 | |

| BioProject ID | PRJNA277925 | |

| GOLD ID | Gp0115795 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source Material Identifier | DSM 100439 |

| Project relevance | Bioprospecting |

Growth conditions and genomic DNA preparation

A pure culture of the isolated Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 was cultivated on 50 ml LB media for 18 h at 60 °C. After harvesting the cells by centrifugation at 8,000 x g for 10 min high-molecular DNA for sequencing was obtained using a modified method of Marmur [34]. In short: The pellet was suspended in a solution of 1 mg/ml Lysozyme (Sigma 62971) in 10 mM TE buffer (pH 8) and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. After a Proteinase K treatment (40mg/ml final concentration, Sigma P6556) at 37 °C for 15 min, a final concentration of 1 % SDS was added and the solution was incubated at 60 °C for 5 min until clearance of the solution. A final concentration of 1 M sodium perchlorate (Sigma-Aldrich 410241) was added and the solution well mixed, before an equal volume of Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamylalcohol (25:24:1) was added and the solution gently shaken on a Vortexer for 10 min. After centrifugation at 5,000 x g for 10 min the upper phase was collected and the nucleic acids again extracted twice with Chloroform:Isoamylalcohol (24:1). The nucleic acids was precipitated with 2 volumes of ice cold 100 % ethanol on ice for 60 min, washed in 70 % ethanol, dried and dissolved in 2 ml solution of 50 μg/ml RNase A (R6513 [Sigma]) in TE buffer for RNase treatment at 37 °C for 30 min. One deproteinizing step with Chloroform:Isoamylalcohol was performed as above. A final concentration of 0.3M Sodium Acetate pH 5.2 was added to the DNA solution and the DNA was precipitated using 100 % ethanol as described above. The dried pellet was dissolved in 100 μl 10 mM Tris.HCL (pH = 8) over night at 4°C.

Genome sequencing and assembly

Approximately 200 μg of genomic DNA was submitted for sequencing. In short, a library was prepared using Pacific Biosciences 10 kb library preparation protocol. Size selection of the final library was performed using BluePippin (Sage Science). The library was sequenced on Pacific Biosciences RS II instrument using P4-C2 chemistry. In total, two SMRT cells were used for sequencing. Raw reads were filtered and de novo assembled using SMRT Analysis v. 2.1 and the protocol HGAP v2 (Pacific Biosciences) [35]. The consensus polishing process resulted in a highly accurate self-overlapping contig, as observed using Gepard dotplot [36], with a length of 3,426,502 bp, in addition to a self-overlapping 45,474 bp plasmid. Circularization and trimming was performed using Minimus2 included in the AMOS software package [37]. The circular chromosomal contig and plasmid was polished and consensus corrected twice using the RS_Resequencing protocol in SMRT Analysis v. 2.1. The final polishing resulted in a 3,410,035 bp finished circular chromosome and a 32,689 bp circular plasmid, with a consensus concordance of 99.9 %. The chromosome was manually reoriented to begin at the location of the dnaA gene.

Genome annotation

The protein-coding, rRNA, and tRNA gene sequences were annotated using Prodigal v. 2.6 [38], RNAmmer v. 1.2 [39] and Aragorn v. 1.2 [40] as implemented in the Prokka automatic annotation tool v. 1.11 [32].

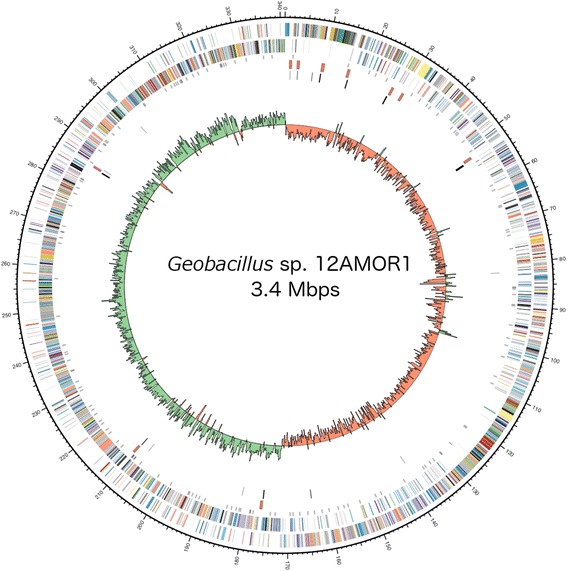

Genome properties

The genome of Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 includes one plasmid of 32,689 bp (47 % G + C content), with one circular chromosome of 3,410,035 bp (52 % G + C content). The main chromosome contained 10 rRNA operons and 88 tRNAs and predicted to encode 3323 protein-coding genes (Table 3 and Fig. 3). 2454 of the protein-coding genes were assigned to a putative function. Identification of peptidases and carbohydrate-degrading enzymes was performed using the MEROPS peptidase database [41] and dbCAN [42], respectively. Using the PHAST web server for the detection of prophages [43], two prophage regions were detected, one intact (56.1Kb: 2476493–2532633) and one incomplete (7.7 Kb: 2811872–2819623). 46 % of the intact prophage protein-coding genes were related to the deep-sea thermophilic bacteriophage GVE2 (NC_009552). The 32.7 Kbps plasmid encoded 34 protein-coding genes.

Table 3.

Summary of genome: one chromosome and one plasmid

| Lable | Size (Mb) | Topology | RefSeq ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | 3.4 | circular | NZ_CP011832.1 |

| Plasmid | 0.32 | circular | NZ_CP011833.1 |

Fig. 3.

Circular representation of the Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 draft genome displaying relevant genome features. Circles representing the following (from center to outside): 1, G + C skew [(G – C)/(G + C) using a 2-kbp sliding window] (green, positive G + C skew; red, negative G + C skew); 2, tRNAs (black); 3, rRNA operons (red); 4, CDS with signal peptides; 5, Coding DNA sequence (CDS) on the reverse strand; 6, CDS on the forward strand. Colour coding of CDS was based on COG categories. The figure was build using Circos version. 0.67-6 [54]

Insights from the genome sequence

The genome of Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 encodes for 3323 protein-coding genes (Table 4). Of those proteins 26.15 % could not be annotated towards a specific function and remain hypothetical. In total, 92.66 % of the proteins could be assigned to a COG functional category. The COG functional categories included replication, recombination and repair (9.4 %); amino acid transport and metabolism (6.9 %); inorganic ion transport and metabolism (3.9 %); energy production and conversion (4.17 %); cell wall/membrane/envelop biogenesis (3.7 %) and carbohydrate transport and metabolism (3.8 %) amongst others (Table 5). In the dbCAN analysis, 108 proteins were assigned for one or more functional activities within the CAZy families, which catalyzes the breakdown, biosynthesis or modification of carbohydrates and glycoconjugates [44, 45]. Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 hydrolyzes starch, dextrin, gelatin, casein and DNA, and utilized sugars such as D-glucose, D-galactose, D-mannose, D-maltose, D-lactose, D-melibiose, D-saccharose, D-trehalose, D-raffinose and glycogen. CDSs encoding for enzymes to metabolize the above mentioned substrates were identified by genome prediction, homology search or mapping onto pathways using the KEGG Automatic Annotation Server [46] server. Furthermore, the isolate was able to grow on the complex carbon polymers xylan, chitin and α-cellulose, however the pathways for such polymer degradation were not identified in the genome. In contrast, pathways for utilization of D-mannitol, arbutin and salicin were identified, although utilization involving acid production was not observed. In comparison with other Geobacillus strains, 12AMOR1 harbors less gene modules involved in hydrolysis and utilization of complex carbohydrates [8, 12].

Table 4.

Statistic of chromosomal genome, including nucleotide content and gene count levels

| Attribute | Value | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 3,410,035 | 100.00 |

| DNA coding (bp) | 2,936,125 | 86.1 |

| DNA G + C (bp) | 1,775,346 | |

| DNA scaffolds | 1 | |

| Total genes | 3,441 | 100.00 |

| rRNA operons | 10 | |

| rRNA genes | 29 | 0.83 |

| tRNA genes | 88 | 2.5 |

| tmRNA | 1 | 0.03 |

| Protein coding genes | 3,323 | 95.57 |

| Genes with function prediction | 2,454 | 70.58 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 3,079 | 88.55 |

| Genes with signal peptids | 147 | 4.23 |

| Genes assigned to prophages | 92 | 2.65 |

| CRISPR repeats | 4 |

Table 5.

Number of genes associated with general COG functional categories

| Code | Value | %agea | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 146 | 4,4 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 0 | 0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 153 | 4,6 | Transcription |

| L | 313 | 9,4 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 0 | 0 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 31 | 0,93 | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| V | 32 | 0,96 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 92 | 2,8 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 123 | 3,7 | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis |

| N | 41 | 1,2 | Cell motility |

| U | 31 | 0,93 | Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport |

| O | 93 | 2,8 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 136 | 4,1 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 127 | 3,8 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 230 | 6,9 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 65 | 1,9 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 107 | 3,2 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 80 | 2,4 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 132 | 3,9 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 17 | 0,5 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 0 | 0 | General function prediction only |

| S | 1130 | 34 | Function unknown |

| - | 244 | 7,3 | Not in COGs |

athe total is based on the number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome

Enzymes involved in protein degradation have been analyzed using MEROPS. In total 126 proteinases were identified. Of those 18 carried a signal peptide identified by SignalP [47] and could be responsible for the extracellular degradation of proteins. Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 showed strong enzymatic activities for esterase (C4), esterase/lipase (C8), leucine arylamidase, α-chymotrypsin, α-glucosidase, alkaline and acidic phosphatase and weak activity for lipase (C14), valine arylamidase, cysteine arylamidase, β-glucosidase, β-glucuronidase and naphtol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase.

The Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 was screened for the following enzymatic activities; α-amylases, gelatinases, caseinases, lipases, chitinases, xylanases [48–53] and DNase at 60 °C. AG agar plates containing 0.1 % (w/v) yeast extract were used supplemented with 1 % (w/v) starch, 0.5 % (w/v) gelatin, 1 % (w/v) skim milk, 1 % (v/v) olive oil, 1 % (v/v) Tween20, 1 % (v/v) Tween80, 0.5 % (w/v) chitin, 0.5 % (w/v) xylan, respectively. DNase activity was screened on DNase Test Agar (Difco). The strain exhibited hydrolytic enzymatic activity for starch, gelatin, skin milk and DNA (Fig. 4). In addition, growth on plates containing olive oil, chitin and xylan were observed, however no hydrolytic activity could be detected. Putative genes encoding for α-amylase, glycosylase, protease and DNase activity were identified in the genome based on annotation or by homology search (Table 6).

Table 6.

Candidate genes coding for putative amylase, proteinase and DNase activities identified in Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 draft genome

| Putative gene | Annotation | Size (aa) |

|---|---|---|

| Amylase | ||

| GARCT_00588 | alpha-amylase | 555 |

| GARCT_00679 | Neopullulanase | 588 |

| GARCT_00683 | alpha-amylase | 511 |

| GARCT_01758 | Trehalose hydrolase | 563 |

| GARCT_02913 | Glycogen debranching enzyme | 680 |

| Glycosylases | ||

| GARCT_00799 | Lysozyme | 207 |

| GARCT_00912 | Dextransucrase | 903 |

| GARCT_01278 | putative polysaccharide deacetylase PdaA precursor | 327 |

| GARCT_01944 | Rhamnogalacturonan acetylesterase RhgT | 279 |

| GARCT_02324 | 6-phospho-β-glucosidase | 490 |

| GARCT_03212 | Putative lysozyme/beta-N- acetylglucosaminidase precursor | 1279 |

| GARCT_03220 | Putative lysozyme | 772 |

| GARCT_03420 | Sucrose-6-phosphate hydrolase/GH32_beta_fructosidase | 481 |

| Proteases | ||

| GARCT_00241 | Serine protease | 453 |

| GARCT_00377 | Serine protease S01 | 401 |

| GARCT_00795 | Oligoendopeptidase M03 | 607 |

| GARCT_00799 | Peptidase M23 | 208 |

| GARCT_00975 | Oligoendopeptidase M03 | 564 |

| GARCT_01122 | Lon protease | 340 |

| GARCT_01527 | Serine protease | 453 |

| GARCT_01552 | Peptidase M32 | 500 |

| GARCT_01840 | Oligoendopeptidase M03 | 618 |

| GARCT_02099 | Aminopeptidase M29 | 413 |

| GARCT_02390 | Dipeptidase M24 | 353 |

| GARCT_02553 | ATP-dependent Clp proteolytic subunit | 244 |

| GARCT_02603 | Protease | 422 |

| GARCT_02604 | Peptidase U32 | 309 |

| GARCT_02662 | Peptidase M23 | 256 |

| GARCT_02693 | Lon protease 1 | 776 |

| GARCT_02694 | Lon protease 2 | 558 |

| GARCT_02769 | Aminopeptidase M42 | 362 |

| GARCT_02850 | Aminopeptidase M42 | 358 |

| GARCT_02860 | Putative dipeptidase | 471 |

| GARCT_02867 | Neutral protease M04 | 548 |

| GARCT_02978 | Aminopeptidase M17 | 497 |

| GARCT_03009 | Peptidase M23 | 331 |

| GARCT_03106 | ATP-dependent Clp proteolytic subunit | 197 |

| GARCT_03137 | Serine protease S41 | 480 |

| GARCT_03221 | Thermitase | 875 |

| GARCT_03224 | Stearolysin M4/S8 | 1338 |

| GARCT_03453 | Trypsin-like serine protease | 407 |

| DNase | ||

| GARCT_00042 | Putative Ribonuclease YcfH | 257 |

| GARCT_00112 | Ribonuclease III C | 141 |

| GARCT_00224 | Putative deoxyribonuclease YcfH | 251 |

| GARCT_00623 | 3’-5’ exoribonuclease YhaM | 326 |

| GARCT_00659 | Nuclease SbcCd subunitD | 395 |

| GARCT_01396 | Restriction endonuclease | 354 |

| GARCT_01547 | Putative Exonuclease (hypothetical protein) | 421 |

| GARCT_01867 | Extracellular ribonuclease | 309 |

| GARCT_02076 | HNH endonuclease | 420 |

| GARCT_02373 | Exodeoxyribonuclease VII, small subunit | 77 |

| GARCT_02374 | Exodeoxyribonuclease VII, large subunit | 449 |

| GARCT_02456 | Putative endonuclease 4 | 300 |

| GARCT_02557 | HNH Endonuclease | 165 |

| GARCT_02575 | HNH Endonuclease | 184 |

| GARCT_02948 | Endonuclease YokF | 303 |

| GARCT_03029 | Endonuclease YhcR | 461 |

Due to their broad biotechnological applications, such as in food processing, detergents or bioethanol production [17], identifying novel α-amylases is still of biotechnological interest. Five genes encoding for α-amylases of the GH13 family (Table 6) were identified by dbCAN analysis. The neopullulanase (GARCT_00679; AKM17981) was cloned using following primers F: AGG AGA TAT ACC ATG CAA AAA GAA GCC ATT CAC CAC CGC, R: GTG ATG GTG ATG TTT CCA GCT TTC AAC TTT ATA GAG CAC AAA CCC, and expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3). The protein GARCT_00679 was purified in high amounts from E. coli and revealed a melting temperature of 76.4 °C in differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis. As expected this value was elevated from the optimal growth temperature of the isolate. Using purified protein solution on 1 % starch-agar plates only GARCT_00679 showed starch degradation capacity comparable with the reference alpha amylase from B. licheniformis (Sigma-Aldrich) (Fig. 5).

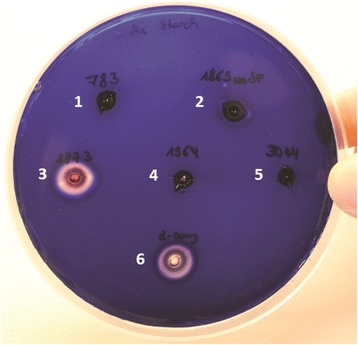

Fig. 5.

Activity of purified Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 alpha-amylases on starch agar plates. As the plate was colored with iodine solution degradation appear as clear zones. 1) Trehalose hydrolase (GARCT_01758), 2) Alpha-amylase (GARCT_00683), 3) Neopullulanase (GARCT_00679), 4) Alpha-amylase (GARCT_00588), 5) Glycogen debranching enzyme (GARCT_02913), 6) Alpha-amylase from B. licheniformis (Sigma-Aldrich)

Conclusions

The starch degrading, thermophilic Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1, isolated from an Arctic deep-sea hydrothermal vent system, revealed a 3.4 Mbp complete genome composed of a circular chromosome and a plasmid. The genome and plasmid have been deposited at GenBank under the accession numbers CP011832 and CP011833, respectively. The genome size within the genus ranges between 3.35 and 3.84 Mbp (RefSeq: NZ_BATY00000000.1; NC_014650.1), therefore Geobacillus. sp. 12AMOR1 belongs with 3.4 Mbp to the smaller genomes. The G + C content of 52 % is within the average of the genus.

16S rRNA analysis identified the isolate belonging to Geobacillus stearothermophilus, whereas DDH analysis with 13 Geobacillus genomes indicated a slightly distant relationship towards the other Geobacillus strains. In the phylogenetic analysis Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 was located in a sub-cluster apart from the type strain G. stearothermophilusDSM 22T within in the same cluster.

When comparing the phenotypical characteristics of diverse G. stearothermophilus strains in the literature, the profile varies from strain to strain [1, 14, 29]. Most of the phenotypical features of Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 lie within those variations. Minor divergences of 12AMOR1 are acid production from potassium 5-ketogluconate and lactose (and maybe gentiobiose), utilization of lactose, and being oxidase positive. Those phenotypical characteristics are not sufficient to support a differentiation between G. stearothermophilus and Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1, even though the DDH analysis suggests a distant relationship.

Although Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 features less genes encoding for carbohydrate degrading enzymes in comparison with other Geobacillus strains, a multiplicity of interesting enzymes, applicable for biotechnology, was identified by genome annotation and by activity screening. Hence, Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 can serve as a source of functional enzymes for future bioprospecting.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Norwegian Research Council (Mining of a Norwegian biogoldmine through metagenomics, project 208491). We would like to acknowledge Frida-Lise Daae at the Centre for Geobiology, University of Bergen for technical assistance during nucleic acid extraction.

Abbreviations

- CAZy

Carbohydrate active enzyme

- GH13

Glycoside hydrolase group 13

- AG

Archaeoglobus medium

Additional files

16S rRNA sequence identities towards Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1. Chosen blast hits with the highest sequence identity (98 %) towards the preliminary partial 16S rRNA gene of Geobacillus sp. strain 12AMOR1 using the megablast algorithm a standalone blastn [23] against 16S ribosomal RNA (Bacteria and Archaea database). (DOCX 14 kb)

Digital DNA-DNA Hybridization of Geobacillus sp.12AMOR1 genome towards other Geobacillus genomes performed by the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) 2.0 using formula 2 (identities/HSP length). The genomes of G. kaustophilus HTA426 [NC_006510.1], G. stearothermophilus strain X1 [CP008855.1], G. stearothermophilus NUB3621 isolate 9A5 [CM002692.1], G. thermoleovorans CCB_US3_UF5 [CP003125.1], G. thermodenitrificans NG80-2 [NC_009328.1], G. vulcani PSS1 [gb|JPOI01000001.1], Geobacillus sp. C56-T3 [NC_014206.1], Geobacillus sp. GHH01 [CP004008.1], Geobacillus sp. JF8 [CP006254.2], Geobacillus sp. WCH70 [CP001638.1], Geobacillus sp. Y4.1MC1 [NC_014650.1], Geobacillus sp. Y412MC52 [NC_014915.1], Geobacillus sp. Y412MC61 [NC_013411.1] was used for comparison. The genome of Bacillus licheniformis ATCC 14580T [NC_006270.3] was used as outgroup. (PDF 67 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: IHS, RS. Performed the isolation and characterization of the isolate: JW. Performed bioinformatics analysis and assembly refinement: RS. Analyzed the data: JW, RS and IHS. Performed enzyme expression, purification and characterization: JW, AEF, KL, AOS. Wrote the paper: JW, RS, HIS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Nazina TN, Tourova TP, Poltaraus AB, Novikova EV, Grigoryan AA, Ivanova AE, et al. Taxonomic study of aerobic thermophilic bacilli: descriptions of Geobacillus subterraneus gen. nov., sp. nov. and Geobacillus uzenensis sp. nov. from petroleum reservoirs and transfer of Bacillus stearothermophilus, Bacillus thermocatenulatus, Bacillus thermoleovorans, Bacillus kaustophilus, Bacillus thermoglucosidasius and Bacillus thermodenitrificans to Geobacillus as the new combinations G. stearothermophilus, G. thermocatenulatus, G. thermoleovorans, G. kaustophilus, G. thermoglucosidasius and G. thermodenitrificans. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2001;51(2):433–46. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-2-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kato T, Haruki M, Imanaka T, Morikawa M, Kanaya S. Isolation and characterization of long-chain-alkane degrading Bacillus thermoleovorans from deep subterranean petroleum reservoirs. J Biosci Bioeng. 2001;91(1):64–70. doi: 10.1016/S1389-1723(01)80113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchant R, Banat IM, Rahman TJ, Berzano M. The frequency and characteristics of highly thermophilic bacteria in cool soil environments. Environ Microbiol. 2002;4(10):595–602. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takami H, Inoue A, Fuji F, Horikoshi K. Microbial flora in the deepest sea mud of the Mariana Trench. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;152(2):279–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu B, Wu S, Song Q, Zhang X, Xie L. Two novel bacteriophages of thermophilic bacteria isolated from deep-sea hydrothermal fields. Curr Microbiol. 2006;53(2):163–6. doi: 10.1007/s00284-005-0509-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchant R, Banat IM, Rahman TJ, Berzano M. What are high-temperature bacteria doing in cold environments? Trends Microbiol. 2002;10(3):120–1. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(02)02311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Logan NA, De Vos P, Dinsdale AE. Genus VII. Geobacillus. In: De Vos P, Garrity GM, Jones D, Krieg NR, Ludwig W, Rainey FA, Schleifer KH, Whitman WB, editors. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, The Firmicutes. 2. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeigler DR. The Geobacillus paradox: why is a thermophilic bacterial genus so prevalent on a mesophilic planet? Microbiology-Sgm. 2014;160:1–11. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.071696-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inthanavong L, Tian F, Khodadadi M, Karboune S. Properties of Geobacillus stearothermophilus levansucrase as potential biocatalyst for the synthesis of levan and fructooligosaccharides. Biotechnol Prog. 2013;29(6):1405–15. doi: 10.1002/btpr.1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain I, Kumar V, Satyanarayana T. Applicability of recombinant beta-xylosidase from the extremely thermophilic bacterium Geobacillus thermodenitrificans in synthesizing alkylxylosides. Bioresour Technol. 2014;170:462–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.07.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antranikian G, Vorgias CE, Bertoldo C. Extreme Environments as a Resource for Microorganisms and Novel Biocatalysts. Adv Biochem Engin/Biotechnol. 2005;96:219–62. doi: 10.1007/b135786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhalla A, Kainth AS, Sani RK. Draft Genome Sequence of Lignocellulose-Degrading Thermophilic Bacterium Geobacillus sp. Strain WSUCF1. Genome Announc. 2013;1(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Wang L, Tang Y, Wang S, Liu RL, Liu MZ, Zhang Y, et al. Isolation and characterization of a novel thermophilic Bacillus strain degrading long-chain n-alkanes. Extremophiles. 2006;10(4):347–56. doi: 10.1007/s00792-006-0505-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nazina TN, Sokolova D, Grigoryan AA, Shestakova NM, Mikhailova EM, Poltaraus AB, et al. Geobacillus jurassicus sp. nov., a new thermophilic bacterium isolated from a high-temperature petroleum reservoir, and the validation of the Geobacillus species. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2005;28(1):43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Espacenet Patent search. In: European Patent Office. http://worldwide.espacenet.com/.

- 16.Zeigler DR. The Genus Geobacillus - Introduction and Strain Catalog. In: Ohio State University DoB, The Bacillus Genetic Stock Center, editor. Bacillus Genetic Stock Center - Catalog of Strains, 7th Edition, Volume 3. 2001

- 17.de Souza PM, de Oliveira Magalhães P. Application of microbial alpha-amylase in industry - A review. Braz J Microbiol. 2010;41(4):850–61. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822010000400004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedersen RB, Thorseth IH, Nygaard TE, Lilley MD, Kelley DS. Hydrothermal Activity at the arctic Mid-Ocean Ridges. Geophys Monogr. 2010;188:67–90. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urich T, Lanzen A, Stokke R, Pedersen RB, Bayer C, Thorseth IH, et al. Microbial community structure and functioning in marine sediments associated with diffuse hydrothermal venting assessed by integrated meta-omics. Environ Microbiol. 2014;16(9):2699–710. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hocking WP, Stokke R, Roalkvam I, Steen IH. Identification of key components in the energy metabolism of the hyperthermophilic sulfate-reducing archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus by transcriptome analyses. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:95. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards U, Rogall T, Blocker H, Emde M, Bottger EC. Isolation and direct complete nucleotide determination of entire genes. Characterization of a gene coding for 16S ribosomal RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17(19):7843–53. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.19.7843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lane DJ. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Auch AF, von Jan M, Klenk HP, Goker M. Digital DNA-DNA hybridization for microbial species delineation by means of genome-to-genome sequence comparison. Stand Genomic Sci. 2010;2(1):117–34. doi: 10.4056/sigs.531120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powers EM. Efficacy of the Ryu nonstaining KOH technique for rapidly determining gram reactions of food-borne and waterborne bacteria and yeasts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61(10):3756–8. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.10.3756-3758.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coorevits A, Dinsdale AE, Halket G, Lebbe L, De Vos P, Van Landschoot A, et al. Taxonomic revision of the genus Geobacillus: emendation of Geobacillus, G. stearothermophilus, G. jurassicus, G. toebii, G. thermodenitrificans and G. thermoglucosidans (nom. corrig., formerly ‘thermoglucosidasius’); transfer of Bacillus thermantarcticus to the genus as G. thermantarcticus comb. nov.; proposal of Caldibacillus debilis gen. nov., comb. nov.; transfer of G. tepidamans to Anoxybacillus as A. tepidamans comb. nov.; and proposal of Anoxybacillus caldiproteolyticus sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62(7):1470–85. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.030346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myhr S, Torsvik T. Denitrovibrio acetiphilus, a novel genus and species of dissimilatory nitrate-reducing bacterium isolated from an oil reservoir model column. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50(Pt 4):1611–9. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-4-1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Norwegian Sequencing Centre (NSC). https://www.sequencing.uio.no/.

- 32.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(14):2068–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(5):541–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marmur J, Doty P. Thermal Renaturation of Deoxyribonucleic Acids. J Mol Biol. 1961;3(5):585. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(61)80023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chin C-S, Alexander DH, Marks P, Klammer AA, Drake J, Heiner C, et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat Meth. 2013;10(6):563–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krumsiek J, Arnold R, Rattei T. Gepard: a rapid and sensitive tool for creating dotplots on genome scale. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(8):1026–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Treangen TJ, Sommer DD, Angly FE, Koren S, Pop M. Next Generation Sequence Assembly with AMOS. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2011;CHAPTER 11:Unit 11.8. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1108s33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rodland EA, Staerfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(9):3100–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laslett D, Canback B. ARAGORN, a program to detect tRNA genes and tmRNA genes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(1):11–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rawlings ND, Morton FR. The MEROPS batch BLAST: a tool to detect peptidases and their non-peptidase homologues in a genome. Biochimie. 2008;90(2):243–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yin Y, Mao X, Yang J, Chen X, Mao F, Xu Y. dbCAN: a web resource for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Web Server issue):445–51. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou Y, Liang Y, Lynch KH, Dennis JJ, Wishart DS. PHAST: a fast phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Web Server issue):347–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cantarel BL, Coutinho PM, Rancurel C, Bernard T, Lombard V, Henrissat B. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37:D233–D8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lombard V, Ramulu HG, Drula E, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014;42(D1):D490–D5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC, Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W182–W5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nature Methods. 2011;8(10):785–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Teather RM, Wood PJ. Use of Congo red-polysaccharide interactions in enumeration and characterization of cellulolytic bacteria from the bovine rumen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;43(4):777–80. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.4.777-780.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kasana RC, Salwan R, Dhar H, Dutt S, Gulati A. A Rapid and Easy Method for the Detection of Microbial Cellulases on Agar Plates Using Gram’s Iodine. Curr Microbiol. 2008;57(5):503–7. doi: 10.1007/s00284-008-9276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vaidya RJ, Macmil SL, Vyas PR, Chhatpar HS. The novel method for isolating chitinolytic bacteria and its application in screening for hyperchitinase producing mutant of Alcaligenes xylosoxydans. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2003;36(3):129–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765X.2003.01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee DG, Jeon JH, Jang MK, Kim NY, Lee JH, Lee JH, et al. Screening and characterization of a novel fibrinolytic metalloprotease from a metagenomic library. Biotechnol Lett. 2007;29(3):465–72. doi: 10.1007/s10529-006-9263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vermelho AB, Meirelles MN, Lopes A, Petinate SD, Chaia AA, Branquinha MH. Detection of extracellular proteases from microorganisms on agar plates. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1996;91(6):755–60. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02761996000600020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berlemont R, Pipers D, Delsaute M, Angiono F, Feller G, Galleni M, et al. Exploring the Antarctic soil metagenome as a source of novel cold-adapted enzymes and genetic mobile elements. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2011;43(2):94–103. doi: 10.1590/S0325-75412011000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krzywinski MI, Schein JE, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, et al. Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19(9):1639–45. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(12):4576–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gibbons NE, Murray RGE. Proposals Concerning the Higher Taxa of Bacteria. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1978;28(1):1–6. doi: 10.1099/00207713-28-1-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schleifer KH. In: Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, The Firmicutes. 2. De Vos P, Garrity GM, Jones D, Krieg NR, Ludwig W, Rainey FA, Schleifer KH, Whitman WB, editors. New York: Springer; 2009. p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- 58.List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60(3):469–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Ludwig W, Schleifer KH, Whitman WB. Class I. Bacilli class. nov. In: De Vos P, Garrity GM, Jones D, Krieg NR, Ludwig W, Rainey FA, Schleifer KH, Whitman WB, editors. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, The Firmicutes. 2. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prévot AR, Prévot AR. In: Dictionnaire des Bactéries Pathogènes. 2. Hauderoy PEG, Guillot G, Hauderoy PEG, Guillot G, Magrou J, Prévot AR, Rosset D, Urbain A, editors. Paris: Masson et Cie; 1953. pp. 1–692. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Skerman V, McGowan V, Sneath P. Approved Lists of Bacterial Names. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1980;30(1):225–420. doi: 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fischer A. Untersuchungen über bakterien. Jahrbücher für Wissenschaftliche Botanik. 1895;27:1–163. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25–9. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]