One of the surprises revealed by comparative genome sequencing is that closely related species share remarkably similar complements of genes. For example, a recent evaluation of the human gene catalog found at most 168 genes without close homologs in mouse or dog, with perhaps as few as 12 representing newly evolved protein-coding regions (1). Moreover, the corresponding genes tend not to differ much in their coding sequences: Nearly 80% of amino acids are identical between orthologous human and mouse proteins (2). Although this leaves many potentially functional coding changes, these observations lend further credence to the proposal, first made more than 30 years ago, that many of the observed differences between species likely stem from when and where the products of the genes are made (3). But what governs these changes in gene expression? There is no shortage of possible explanations—differences in external cues and cellular milieus, in how genomes are packaged, in the proteins that control transcription, and in the regulatory sequences to which they bind. Strikingly, on page 434 of this issue (4), Wilson et al. show that in human and mouse liver cells, the differences in regulatory sequences dominate all other factors.

Wilson et al. took advantage of an ideal system: a mouse model of Down syndrome in which mouse cells contain a copy of human chromosome 21 in addition to the complete mouse genome (5). In these cells, the human DNA sequence is placed in an otherwise murine context, including all external and cellular cues as well as regulatory proteins. This system allowed the authors to ask an otherwise impossible question: Is regulation of the genes on human chromosome 21 in these mouse cells (Tc1 hepatocytes) determined by the human DNA sequence, or by the mouse cellular environment and transcriptional machinery?

The authors compared the regulation of human genes in Tc1 cells to those of their mouse orthologs in these same cells. They then compared the observed patterns to those in mouse hepatocytes from littermates that did not inherit the extra human chromosome, as well as to those in normal human hepatocytes. The authors first confirmed that the protein binding and expression patterns of mouse genes in Tc1 hepatocytes match those in normal mouse hepatocytes, and that both differ from patterns for orthologous genes in human cells. What about the human genes in the Tc1 hepatocytes? If regulation is driven largely by sequence, then these genes should be regulated just as they are in normal human hepatocytes, whereas if species-specific developmental context, epigenetic factors, or differences in transcription factors themselves play a defining role, then the genes should most closely mimic their mouse orthologs.

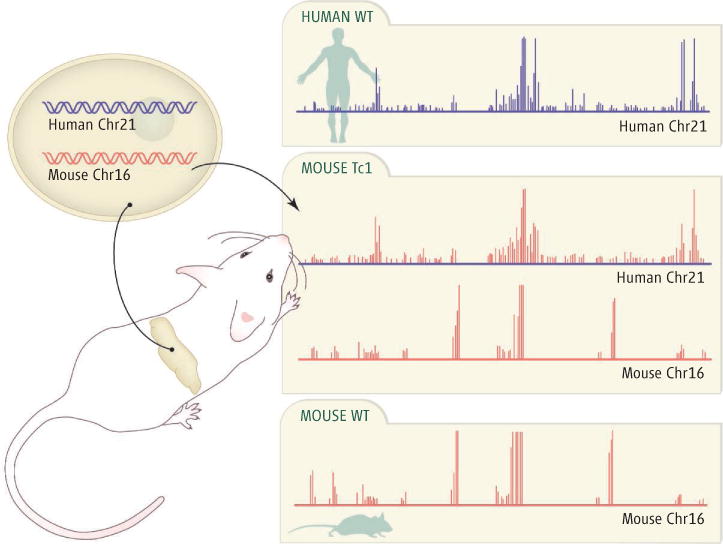

The authors compared regulation at three levels: binding of transcription factors to DNA, modification of histones [proteins that bind chromosomal DNA and determine its packing and accessibility for binding (6)], and gene expression. The results were clear. The binding patterns of transcription factors HNF1α, HNF4α, and HNF6 on human chromosome 21 in mouse cells matched those seen in human cells, not those observed in mouse cells, with only a few exceptions (see the figure). Similarly, although histone H3K4me3 modifications at canonical transcription start sites were largely shared between the human and mouse chromosomes, these same modifications at other sites (thought to represent unannotated promoters) showed human-specific patterns on human chromosome 21 in Tc1 cells. Finally, gene expression (the amount of messenger RNA transcribed) from human chromosome 21 genes in Tc1 hepatocytes was more closely correlated to the expression of human chromosome 21 genes in human hepatocytes than to the expression of their mouse orthologs in the Tc1 cells. The authors thus concluded that it is the regulatory DNA sequence, rather than any other species-specific factor, that is the single most important determinant of gene expression.

Figure. Reading the regulatory code.

Transcription factor proteins in mouse Tc1 cells carrying a human chromosome (middle) bind to the human DNA in a human-specific pattern (top) and to the corresponding mouse DNA in a mouse-specific pattern (bottom).

This result raises many interesting questions about the transcriptional regulatory code. Wilson et al. show that the information required for species-specific regulation is encoded in cis-regulatory DNA sequence. Yet because essentially all of human chromosome 21 is present, the data do not address whether the code is local. The results are consistent with either a few regulatory sites for each gene close to the corresponding start of transcription, or many interacting regulatory sites scattered across large swaths of human chromosome 21. Experiments that replaced a mouse gene by its human ortholog along with varying lengths of upstream and downstream regions might address how much human sequence is needed to recapitulate a human pattern of binding and expression. Would a few kilobases upstream be sufficient, as would be expected if only proximal transcription factor binding sites matter, or would much larger segments upstream and downstream be required, indicating that multiple types of poorly understood sequence elements are acting in concert?

The paper’s findings also call into question one of the basic tenets of comparative genomics: that evolutionary conservation can serve as the primary tool for finding functional sequences (2, 7, 8). Clearly, nonconserved sequences are responsible for the observed functional differences in binding and expression of human and mouse genes in the same cells. Thus, although many conserved noncoding sequences are functional, and interspecies comparisons can help us to identify these motifs, narrowing our attention only to these sequences must result in an incomplete understanding of the regulatory code (9). Indeed, this approach guarantees missing the species-specific regulatory instructions that make us different from mice.

Finally, the transcriptional machinery of a mouse cell is able to read out human-specific gene expression instructions based solely on the sequence of the human chromosome, but today’s bioinformatic methods cannot. Substantial progress has been made in predicting expression from sequence in yeast (10, 11), whereas in mammals, known regulatory sequences are too short and degenerate, and extend too far from the start of transcription, for us to accurately predict gene expression from sequence information alone. So what would it take for us to predict how mouse cells would read out the regulatory code of, say, an armadillo chromosome, without doing the experiments? That is, how can we move toward reading the regulatory code as easily as we read the genetic code, which allows us to seamlessly go from the DNA sequence to the protein complement of any species? We anticipate that deciphering the regulatory code will require a combination of computational and experimental approaches, in concert with improved physical models of protein-DNA interaction (12). It will also require an understanding of the cellular context to an extent not necessary for the genetic code, because the complement of regulatory proteins operating to control transcription varies with the species, the cell type, and the environment. The ENCODE project provides one model of experimentally monitoring all accessible regulatory readouts, such as transcription itself, binding of regulatory proteins, histone modification states, and nucleosome positioning on a global scale (13). Our hope is that innovative approaches to the analysis of ENCODE-like data will ultimately allow us to crack the regulatory code.

Differences in regulatory DNA sequences drive species-specific gene expression.

Contributor Information

Hilary A. Coller, Email: hcoller@princeton.edu.

Leonid Kruglyak, Email: leonid@genomics.princeton.edu.

References

- 1.Clamp M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709013104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waterston RH, et al. Nature. 2002;420:520. doi: 10.1038/nature01262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King MC, Wilson AC. Science. 1975;188:107. doi: 10.1126/science.1090005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson MD, et al. Science. 2008;322:434. doi: 10.1126/science.1160930. published online 11 September (2008 10.1126/science.1160930) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Doherty A, et al. Science. 2005;309:2033. doi: 10.1126/science.1114535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Science. 2001;293:1074. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang QF, et al. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-1-r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie X, et al. Nature. 2005;434:338. doi: 10.1038/nature03441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li XY, et al. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e27. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beer MA, Tavazoie S. Cell. 2004;117:185. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harbison CT, et al. Nature. 2004;431:99. doi: 10.1038/nature02800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moses AM, et al. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birney E, et al. Nature. 2007;447:799. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]