Abstract

Purpose

This study predicted the effects of velopharyngeal (VP) anatomical parameters on VP function to provide a greater understanding of speech mechanics and aid in the treatment of speech disorders.

Method

We created a computational model of the VP mechanism using dimensions obtained from magnetic resonance imaging measurements of 10 healthy adults. The model components included the levator veli palatini (LVP), the velum, and the posterior pharyngeal wall, and the simulations were based on material parameters from the literature. The outcome metrics were the VP closure force and LVP muscle activation required to achieve VP closure.

Results

Our average model compared favorably with experimental data from the literature. Simulations of 1,000 random anatomies reflected the large variability in closure forces observed experimentally. VP distance had the greatest effect on both outcome metrics when considering the observed anatomic variability. Other anatomical parameters were ranked by their predicted influences on the outcome metrics.

Conclusions

Our results support the implication that interventions for VP dysfunction that decrease anterior to posterior VP portal distance, increase velar length, and/or increase LVP cross-sectional area may be very effective. Future modeling studies will help to further our understanding of speech mechanics and optimize treatment of speech disorders.

Several studies have examined the variability in velopharyngeal (VP) muscle measures in healthy individuals (Perry, Kuehn, & Sutton, 2013; Perry, Kuehn, Sutton, & Gamage, 2014); however, the direct effects of this variability on normal and abnormal function are not well understood. One study demonstrated a significant gender effect for VP muscles among an adult population (Perry, Kuehn, Sutton, & Gamage, 2014). These findings were not observed in a prepubertal child population (N = 34), demonstrating that gender effects appear to be dependent on age (Kollara, Perry, & Hudson, 2014). Significant variation in VP muscle anatomy compared with noncleft anatomy has been associated with hypernasal speech among adults with repaired cleft palate (Ha, Kuehn, Cohen, & Alperin, 2007). Furthermore, variations in cleft infant anatomy compared with noncleft controls have been demonstrated (Kuehn, Ettema, Goldwasser, & Barkmeier, 2004; Kuehn, Ettema, Goldwasser, Barkmeier, & Wachtel, 2001; Perry, Kuehn, Sutton, Goldwasser, & Jerez, 2011). Understanding the effect of anatomical variability on VP mechanics is essential for developing effective treatments and interventions for VP dysfunction. The development of these treatments can be accelerated by using advanced imaging (Perry et al., 2013; Sutton, Conway, Bae, Seethamraju, & Kuehn, 2010) and computational modeling techniques (Inouye, Pelland, Lin, Borowitz, & Blemker, 2014) that can reveal important insights into the mechanical interactions between VP anatomy and function.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been used to study the geometry of the VP mechanism and the surrounding structures (e.g., Akgüner, 1999; Bae, Kuehn, Sutton, Conway, & Perry, 2011; Beer et al., 2004; Kollara & Perry, 2013; Tian & Redett, 2009). MRI studies have examined the soft palate (velum); the VP port; and the levator veli palatini (LVP) muscle, which is the primary muscle for VP closure. It has been hypothesized that specific dimensional features of VP anatomy are essential to producing the VP closure necessary for typical speech production (Perry et al., 2011; Perry, Sutton, Kuehn, & Gamage, 2014). These MRI studies have identified morphological variations between normal and cleft palate VP anatomy. Perry, Sutton, et al. (2014) used structural and dynamic MRI to assess LVP muscle contraction at the sentence level with high imaging speeds among 10 children with normal anatomy. These and other recent dynamic imaging advances (e.g., Scott, Boubertakh, Birch, & Miquel, 2013) provide insight into the relationship between VP anatomy and function in typical speech. Because dynamic MRI methods for LVP muscle contractions have been limited to small, homogeneous sample sizes, researchers have been unable to demonstrate a connection between variable anatomies, such as cleft palate anatomy, and the effect of these variations on the VP function.

The use of computational models to investigate form–function relationships and develop treatment protocols has increased dramatically in the past several decades (Inouye et al., 2014; Neptune, 2000; Valero-Cuevas, Hoffmann, Kurse, Kutch, & Theodorou, 2009) and empowers us to develop a mechanistically based understanding of VP function. For example, computational modeling can systematically investigate cause–effect relationships that are impossible to accomplish in vivo and/or take decades of clinical trials to elucidate. Previous computational models have provided insight into the mechanics of the VP mechanism (Berry, Moon, & Kuehn, 1999; Inouye et al., 2014; Srodon, Miquel, & Birch, 2012); however, these models have not explored how anatomical variability influences VP function.

The goal of this work was to integrate quantitative anatomical information obtained from MRI and the known properties of the velum (Birch & Srodon, 2009; Cheng, Gandevia, Green, Sinkus, & Bilston, 2011; Ettema & Kuehn, 1994; Kuehn & Kahane, 1990) and skeletal muscle (Blemker, Pinsky, & Delp, 2005; Gordon, Huxley, & Julian, 1966; Zajac, 1989) into a computational model to investigate how variations in VP anatomy across the normal population influence VP function (see Figure 1). In particular, this study aimed to (a) develop a model that accurately predicts experimental data, (b) simulate a large sample of random anatomies on the basis of distributions of MRI data collected from adult subjects, and (c) quantify the effects of isolated anatomical parameter changes on VP function.

Figure 1.

Inputs of velopharyngeal anatomical parameters and mechanical properties of muscle and the soft palate were used to create a computational model for assessing velopharyngeal function. MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; LVP = levator veli palatini.

Method

Subjects

In accordance with the local institutional review boards, 10 healthy male subjects with normal anatomy participated in the study. The use of male subjects eliminated the effect of gender, as gender has been shown to have a significant effect on VP parameters (Perry, Kuehn, Sutton, & Gamage, 2014; Perry, Kuehn, Sutton, Gamage, & Fang, 2014) and VP function (Kuehn & Moon, 1998; McKerns & Bzoch, 1970). Subjects were White native English speakers between 19 and 24 years of age (M = 21 years, SD = 1.5 years). Subjects displayed normal head and neck anatomy and had no history of neurological, swallowing, or hearing abnormalities. Perceptual speech assessments (by a speech-language pathologist) confirmed normal speech and oral-to-nasal resonance.

MRI

Methods for imaging subjects have been previously described (Perry et al., 2013; Sutton et al., 2010). In brief, subjects were scanned using a Siemens (Berlin, Germany) 3 T Trio and a 12-channel head coil. Imaging was obtained in the supine position while subjects were instructed to breathe through the nose with the mouth closed. A Velcro®-fastened elastic strap was placed around the subject's head, passing over the glabella, and fastened to the head coil to reduce motion during the scanning session. A high-resolution, T2-weighted turbo spin echo anatomical scan, sampling perfection with application optimized contrasts using different flip angle evolution (SPACE), was used to acquire three-dimensional data of the oropharyngeal anatomy (dimensions = 25.6 × 19.2 × 15.5 cm) with 0.8 mm isotropic resolution. The acquisition time was slightly less than 5 min (4 min 52 s). Echo time was 268 ms, and repetition time was 2.5 s. Static MRI data were used for the present study to determine the morphology of the VP mechanism among subjects.

Model Creation From MRI Measurements

Measures used in the present study have been previously described and used routinely in studies of the VP mechanism using MRI (Ettema, Kuehn, Perlman, & Alperin, 2002; Ha et al., 2007; Perry et al., 2013; Perry, Sutton, Kuehn, & Gamage, 2014; Tian & Redett, 2009). Measures from the MRI images included the LVP, velum, and posterior pharyngeal wall (see Figure 2a and Tables 1 and 2). The LVP major and minor axis measurements—anterior-to-posterior and superior-to-inferior distances, respectively, as in Perry et al. (2013)—were combined to calculate the cross-sectional area measurement. Values were used to create line segment representations of the velum, LVP, and posterior pharyngeal wall (see Figure 2b). Line segment components were oriented in the corresponding MRI image planes (see Figure 2c) to create a three-dimensional model (see Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

(a) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measures in the sagittal and oblique-coronal image planes. (b) Line segments represent the velum, levator veli palatini (LVP), and posterior pharyngeal wall (PPW). Width of posterior pharyngeal wall line segment was based on the velopharyngeal (VP) width measurement. The velum line segment extends down to the middle of the LVP, not along the nasal surface. (c) Orientation of the components with the MRI planes. (d) Computational model in the orientation shown in Panel C. (e) Model components reflect anatomical representation (Perry & Kuehn, 2007).

Table 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging measures for model creation.

| Measurement | Description |

|---|---|

| Sagittal plane | |

| LVP major axis | Largest cross-sectional diameter of the LVP along the midline of the velum |

| LVP minor axis | Smallest cross-sectional diameter of the LVP along the midline of the velum |

| Velum–LVP angle | Angle between the line connecting the tip of the posterior nasal spine and the middle of the LVP and the line of the oblique-coronal plane |

| Velar length | Effective velar length extending from the posterior nasal spine to the velar knee |

| Velar thickness | Thickness of the velum measured from the velar dimple to the velar knee (coursing through the bulk of the cross-sectional LVP muscle) |

| Oblique-coronal plane measurement | |

| Distance between points of origin | Distance between the LVP points of origin at the base of the skull |

| VP width | Width of the VP port |

| VP distance | Depth (anterior-to-posterior distance) of the VP port through the midline |

| Extravelar LVP length | Length of the LVP muscle between the point of origin and the region where the LVP enters the body of the velum. This represents the segment of the LVP muscle that is outside the body of the velum. |

| Intravelar LVP length | Distance between the points of LVP entry into the velum |

Note. LVP = levator veli palatini; VP = velopharyngeal.

Table 2.

Velopharyngeal (VP) dimensions on the basis of magnetic resonance imaging measurements from 10 healthy adults.

| Measurement | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| LVP cross-sectional area (mm2) | 35.0 | 4.65 |

| Velum–LVP angle (°) | 78.5 | 5.23 |

| Velar length (mm) | 13.6 | 1.82 |

| Velar thickness (mm) | 12.0 | 1.34 |

| Distance between points of origin (mm) | 59.3 | 4.89 |

| VP width (mm) | 17.2 | 3.57 |

| VP distance (mm) | 10.9 | 2.27 |

| Extravelar LVP length (mm) | 35.3 | 3.08 |

| Intravelar LVP length (mm) | 26.5 | 1.60 |

Note. LVP = levator veli palatini.

Modeling Assumptions and Intrinsic Parameters

Muscle properties from a previous study (Blemker, Pinsky, & Delp, 2005) were implemented for the LVP and contained both passive (related to passive muscle stretch) and active (related to muscle activation and muscle stretch) nonlinear tensile components. The active tensile component incorporates the known force–length behavior of skeletal muscle (Gordon, Huxley, & Julian, 1966), where the peak muscle force occurs when the muscle reaches its optimal length (see Figure 3) of λ muscle = 1, where λ muscle is the muscle stretch ratio (e.g., λ muscle = 1 is 100% rest position with no contraction and λ muscle = 0.8 is 80% rest position or 20% shortened from rest). Because the muscle fibers run parallel to the line of action of the muscle, we assumed that the maximal muscle force was proportionate to the muscle cross-sectional area. Cross-sectional area was calculated from the major and minor axis measurements by approximating the cross-section shape as an ellipse:

Figure 3.

The force–length properties of skeletal muscle were used to calculate active muscle tension on the basis of the amount of contraction. A higher amount of contraction from a 100% rest position lessens muscle force-generating capacity. LVP = levator veli palatini.

We varied the parameter of muscle specific tension (equal to the maximum force per unit area, also called peak isometric stress) so the average model (from the 10 subjects) would reproduce previously published experimental data of VP closure force (Kuehn & Moon, 1998). In iterating across a range of values, we found that 0.03 MPa generated computational data within 1 SD of all experimental data. (See the Discussion section for further details and a parameter sensitivity analysis.)

The velum was modeled as a simple spring with a Young's modulus of 1 kPa (Birch & Srodon, 2009) and a cross-sectional area defined by the multiplication of the velar thickness and the VP width (which we assumed was equal to the velar width). The force exerted by the velum was therefore determined from its extension, with the force equal to

where CSA velum is the velar cross-sectional area, E velum is the velum stiffness or Young's modulus, and λ velum is the stretch ratio of the velum.

The posterior pharyngeal wall was modeled as a rigid (nonmoving) body (a simplification also used by Berry et al., 1999) against which the velum would make contact. The width of this contact was set to the VP width measurement. The configurations of the LVP, velum, and posterior pharyngeal wall during LVP relaxation and LVP contraction producing closure were determined (see Figure 4a and 4b), and then the force calculations were based on the geometry of the VP closure configuration and corresponding static force balance (see Figure 4c). The force of the velum in the sagittal plane would naturally pull the LVP out of the oblique coronal plane. Therefore, a force equal to the velum force was applied in the downward direction in the sagittal plane to keep the LVP in the oblique-coronal plane (see Figure 4c, sagittal plane). This force represented known contributions (Seaver & Kuehn, 1980) from other soft tissue and palatal muscles that would pull the velum downward (e.g., palatopharyngeus and palatoglossus).

Figure 4.

Line segment model configuration for (a) relaxed levator veli palatini (LVP), (b) LVP during velopharyngeal (VP) closure, and (c) determining closure force calculations using a simple force balance.

LVP activation, ranging from 0% to 100%, was used as an input variable, and the output quantities of interest were the magnitude of the total force exerted on the posterior pharyngeal wall (VP closure force) and the minimum activation required from the LVP muscle to achieve closure.

Computational Simulations

We conducted three sets of computational simulations (see Figure 5). The first set of image-based simulations comprised 10 models, each from the MRI images of the individual subjects. The second set of randomized simulations comprised 1,000 randomized simulations, with each parameter drawn independently from a uniform probability distribution varying between the mean ± 1 SD for each anatomy, as in a previous study (Santos & Valero-Cuevas, 2006). The third set of parameter isolation simulations consisted of simulations in which each parameter was varied up and down 1 SD from its mean and other parameters were held at their mean values. These simulations quantified and ranked the importance of each anatomical parameter. Each parameter change affected the model anatomy in different ways, sometimes changing multiple basic measurements simultaneously (see Figure 6).

Figure 5.

We conducted three sets of computational simulations with our model. The first simulation set comprised 10 image-based simulations, each from the magnetic resonance images of the individual subjects, as well as an averaged simulation. The second set was 1,000 randomized simulations with each parameter drawn independently from a uniform probability distribution varying between the mean ± 1 SD for each anatomy. The third set was parameter isolation simulations that adjusted each parameter up and down 1 SD from the mean while holding other parameters constant to determine sensitivity of velopharyngeal closure to individual parameters.

Figure 6.

Effects of parameter adjustments on model anatomy. Velopharyngeal (VP) distance increased by moving the posterior pharyngeal wall (PPW) posteriorly in the oblique-coronal plane. Extravelar levator veli palatini (LVP) length increased by moving the points of origin posteriorly in the oblique-coronal plane. Intravelar LVP length increased by increasing the width of the intravelar segment while keeping the origin-to-origin distance and extravelar LVP length constant. This moved the points of origin posteriorly in the oblique-coronal plane. Distance between points of origin remained constant. VP width increased by widening the PPW contact area. Distance between points of origin increased while keeping extravelar LVP length constant. Velum–LVP angle increased by rotating the velum anteriorly in the sagittal plane. Velar length increased by extending the point of attachment to the hard palate posteriorly and superiorly while keeping the velum–LVP angle constant.

Definition of Anatomical Parameter Variations

The anatomical parameter variations in the model were defined such that the combined set of parameters could uniquely define a particular anatomy and that the anatomical parameters could be varied independently of one another (see Figure 6). VP distance (i.e., depth of the VP portal) was increased by moving the posterior pharyngeal wall posteriorly in the oblique-coronal plane. Extravelar LVP length was increased by moving the points of LVP muscle origin posteriorly in the oblique-coronal plane while keeping the side-to-side distance between points of origin constant. Intravelar LVP length was increased by increasing the width of the intravelar segment while keeping the origin-to-origin distance and extravelar LVP length constant. This moved the points of origin posteriorly in the oblique-coronal plane. VP width was increased by widening the posterior pharyngeal wall contact area. Distance between points of origin was increased while keeping extravelar LVP length constant. The velum–LVP angle was increased by rotating the velum anteriorly in the sagittal plane. Velar length was increased by extending the point of attachment to the hard palate posteriorly and superiorly while keeping the velum–LVP angle constant. Velar thickness was increased in simulation by increasing the velar cross-sectional area. The LVP cross-sectional area was increased in simulation by increasing the maximal force of the muscle.

Results

The variability of the individual models in the image-based simulations and the randomized simulations mirrors the observed experimental variability (see Figure 7a). The standard deviations of the experimental data points are as large as 50% or more of the mean. The individual models also deviate around 50% or more in closure force from the mean. This suggests that the large standard deviations of the experimental data may be a result of anatomic variability. Furthermore, the similar relative variability of closure force in experimental and model data provides further support for the predictive power of the model.

Figure 7.

(a) The average model agrees well with experimental data, falling within 1 SD of all data points. Individual models from magnetic resonance imaging scans (a) and randomized models (b) show variability similar to that observed experimentally.

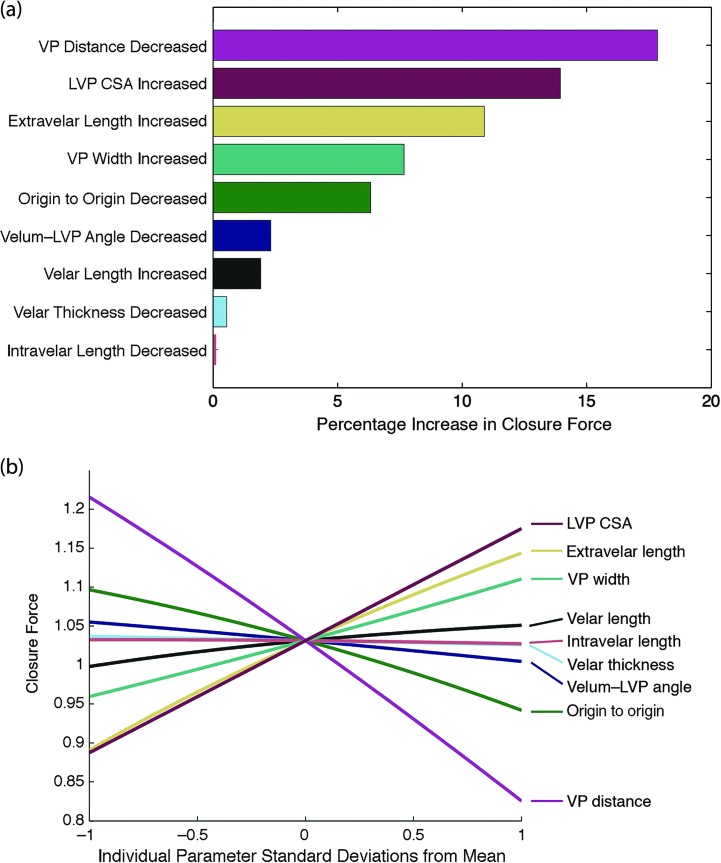

The parameter isolation simulations reveal that decreasing VP distance by 1 SD increases closure force and decreases minimum activation required more than any other parameter adjustment of 1 SD from the mean (see Figures 8 and 9). This highlights the importance of VP distance in creating adequate VP closure during speech. The model suggests that increased VP distance may be one of the main contributing factors to VP insufficiency.

Figure 8.

Parameter isolation simulations. (a) Ranked parameter sensitivities measured by percentage increase in closure force when varying parameters up or down 1 SD from the mean and holding other variables constant. (b) Closure force has positive relationships with isolated increases in some variables and negative relationships in others. VP = velopharyngeal; LVP = levator veli palatini; CSA = cross-sectional area.

Figure 9.

Parameter isolation simulations. (a) Ranked parameter sensitivities measured by percentage decrease in minimum activation required. (b) Minimum activation required has positive relationships with isolated increases in some variables and negative relationships in others. VP = velopharyngeal; LVP = levator veli palatini; CSA = cross-sectional area.

After VP distance, the next parameters most influential on closure force differed from those most influential on minimum activation required. Increasing LVP cross-sectional area and extravelar LVP length were the next parameters most influential on VP closure force. Velum–LVP angle and velar length were the next parameters most influential on minimum activation required. It is interesting to note that the most influential parameters for closure force tended to be those measured in the oblique-coronal plane and related to LVP configuration, whereas the most influential parameters for minimum activation required tended to be those measured in the sagittal plane and related to velar configuration (see Figure 10). VP distance was the most influential predictor of closure force and can be examined in either the oblique-coronal or sagittal imaging planes.

Figure 10.

Parameter isolation simulations (see Figures 8 and 9) enable identification of the most influential aspects of velopharyngeal (VP) closure. It is interesting to note that the most influential parameters for closure force (see Figure 8) tended to be those measured in the oblique-coronal plane and related to levator veli palatini (LVP) configuration, whereas the most influential parameters for minimum activation required (see Figure 9) tended to be those measured in the sagittal plane and related to velar configuration. PPW = posterior pharyngeal wall.

Discussion

In this study, we created a computational model of the LVP, velum, and posterior pharyngeal wall using MRI data from 10 adult subjects with normal anatomy to investigate how variability in anatomies affects VP closure. The model was able to predict closure forces that were, on average, consistent with experimental data. Analysis of the model revealed that anatomical variability has a significant impact on VP closure mechanics. As such, the most advantageous anatomies had more than twice the closure force of the least advantageous anatomies. Sensitivity analysis of the model reveals that some anatomical parameters have a much greater influence on VP mechanics compared with others, suggesting roles of these parameters of interest in normal and abnormal VP function.

One of our central working assumptions was that a higher closure force and a lower minimum activation required are predictors of better VP function, all other variables being equal. If closure force is higher for a given activation (which our study shows occurs for more advantageous anatomies), then less muscle activation is needed in general to produce the same amount of closure force (see Figure 11). This may be important for fatigue avoidance in patients with borderline VP incompetence (Nohara, Tachimura, & Wada, 2006). Furthermore, higher closure force in general should ensure a tighter, more complete VP closure for patients with VP dysfunction. Further validation of these concepts can be achieved in the future by creating models on the basis of anatomical measurements of individuals with VP dysfunction (Drissi et al., 2011; Ha et al., 2007; Ozgür, Tunçbilek, & Cila, 2000). We would predict that, compared with the normal ranges presented here, closure force would be lower and minimum activation required would be higher in models built from patients with VP dysfunction.

Figure 11.

Randomized simulation set, with each data point representing one random anatomy. Higher closure force at full muscle activation, in general, correlates with a lower minimum activation required in our model.

The variability in VP closure metrics for different anatomies in our study is explained by both the geometry of the VP mechanism (see Figure 4) and the force–length relationship of the LVP muscle (see Figures 3 and 12). For instance, in the case of geometry, if the LVP muscle origin-to-origin distance is decreased, closure force increases (see Figures 8 and 9) because of the more favorable angle to produce high closure force. The VP distance had the largest effect on closure force. A large VP distance requires more LVP contraction, thereby decreasing the force capacity of the muscle, and vice versa (see Figure 12). This is due to the intrinsic force–length relationship of muscle.

Figure 12.

Effect of velopharyngeal (VP) distance. A large VP distance requires more levator veli palatini contraction, resulting in less force capacity, and vice versa.

The geometry and the force–length relationships may also be dependent on each other. For instance, increasing the extravelar LVP length in our model makes the geometry more favorable because the angle of muscle force is more backward and therefore favorable for closure. Furthermore, the amount of muscle contraction (measured by percentage of the initial length) required for VP closure is decreased, making the overall LVP muscle force greater.

Although we have demonstrated that some parameters are more influential than others, the measurement of a particular influential parameter, such as VP distance, LVP cross-sectional area, or extravelar LVP length, is not sufficient to predict the VP closure for a given anatomy due to all of the other factors. For example, there is a significant scatter of closure forces over the range of the most important parameters (see Figure 13). There exist some anatomies that have the greatest VP distance (a large disadvantage) but still have higher closure forces than those with the smallest VP distance (a large advantage). This is because other anatomical factors combine to overcome the large VP distance. One implication of this is, for instance, that VP depth cannot be measured in isolation to make inferences about how advantageous the anatomy is to produce VP closure overall. In contrast, our model predicts that, if other factors are held constant, decreasing VP depth (e.g., via surgery) will in general result in an anatomy more advantaged for VP closure.

Figure 13.

Three plots of randomized simulation set, with each data point representing one random anatomy. Although the above anatomical parameters are the most influential, they cannot be considered in isolation of the other parameters because there is considerable variability of closure force for a given value of each individual parameter. Closure force was measured at 100% muscle activation. VP = velopharyngeal; LVP = levator veli palatini.

One of the assumptions of our study is that the LVP resting length corresponds to the optimal length of the muscle (i.e., that the muscle sarcomeres are at their optimal length for force production at rest; Zajac, 1989). The resting sarcomere lengths of the LVP muscle are unknown currently. However, regardless of the actual starting length of the sarcomeres, the force-generating capacity of the LVP will be highly sensitive to the amount of contraction, making anatomic variables that affect the amount of required contraction such as VP distance and extravelar LVP length very influential.

Of interest, the model predicted variability in closure force that resembled the variability in the published VP closure force data (Kuehn & Moon, 1998), suggesting that variability in VP function across individuals may be due to anatomical variability. Other studies have found similar effects of anatomical variability in the context of speech (Brunner, Fuchs, & Perrier, 2009; Finkelstein, Talmi, Nachmani, Hauben, & Zohar, 1992; Ha et al., 2007). However, it should be noted that in addition to the anatomical variability, the measurement variability of the electromyography data and closure force sensors, gender differences, and minor contributions of other palatal muscles to closure are factors that could contribute to the scatter of the data in the experimental study (Kuehn & Moon, 1998).

The simplicity of our model has both significant advantages and drawbacks. Advantages include a low computational cost (enabling a thousand simulations in only a few seconds) and ease of adjusting specific parameters in isolation. The main drawback of this approach is that it necessitates the exclusion of several more complex factors, such as other muscles' contributions to closure force, curvature of the intravelar LVP segment, dynamic and viscoelastic effects on tissue deformation, consideration of more complex tissue geometries, pharyngeal wall movement, Passavant's ridge, and movement of the LVP outside the original oblique-coronal plane. Future research that reduces the computational cost of more complex computational modeling techniques, such as finite-element models (Blemker et al., 2005; Inouye et al., 2014), will empower the exploration of these complexities.

Because the musculus uvulae is intrinsic to the velum, a line segment model is not conducive to modeling its contribution to closure using the proposed methods. During VP closure, the musculus uvulae likely facilitates VP closure by adding stiffness to the nasal velar surface and providing additional muscle bulk to fill the VP gap (M. Huang, Lee, & Rajendran, 1997). It has not be confirmed with imaging data in vivo whether individuals with repaired cleft palate demonstrate a musculus uvulae, although fibers have been distinctly reported in one histologic study of cleft infant specimens (Landes et al., 2012). However, nasendoscopy studies providing an indirect view of the musculus uvulae and other histology studies have suggested an absent or hypoplastic musculus uvulae (Azzam & Kuehn, 1977; Lewin, Croft, & Shprintzen, 1980; Pigott, Bensen, & White, 1969). In normal VP function, the actual closure force and minimum activation required are likely representative of the combined contributions of the LVP and musculus uvulae fibers rather than the LVP alone. The contribution of the musculus uvulae to VP function has never been quantified and is deserving of further research. However, given its very small size relative to the LVP, we assume that variations in the LVP muscle, velum, and VP port geometry contribute more to our quantitative metrics of closure force and minimum activation required than do variations in the musculus uvulae.

Assumptions regarding specific parameters in the model—in particular, the stiffness of the velum and the specific tension of the LVP muscle—should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. The Young's modulus of the velar tissue was assumed to be 1 kPa, which was based on what was found from ex vivo mechanical testing (Birch & Srodon, 2009). Other studies have found a wide range of palate stiffnesses (approximately 0.5–100.0 kPa, depending on the location in the velum; Berry et al., 1999; Cheng et al., 2011; L. Huang, 1995; M. Huang, Riski, Cohen, Simms, & Burstein, 1999; Liu, Luo, Lee, & Lu, 2007; Malhotra et al., 2002). Moreover, our use of 0.03 MPa for the specific tension of muscle is smaller than that reported in previous muscle experimental studies (0.11–0.47 MPa; Fukunaga, Roy, Shellock, Hodgson, & Edgerton, 1996) and that used in modeling studies (0.3–0.61 MPa; Arnold, Ward, Lieber, & Delp, 2010; Blemker et al., 2005). This parameter tuning was used to reproduce the experimental data to provide physiological relevance for the predicted results. This necessary tuning could be due in part to muscle activation measurement factors in the experimental data (Kuehn & Moon, 1998) used for comparison because the activation levels were measured relatively rather than absolutely. For instance, the maximum activation measured experimentally for a subject may have been 20% of physiological maximum but was reported as 100% activation because the data were normalized. Furthermore, the specific tensions of palate muscles have never been measured, but using 0.03 MPa in our models resulted in predictions that correspond well with experimental data. The velum stiffness also plays a role, as simulating a stiffer velum would require more specific tension to stretch the velum for a specific activation.

To quantitatively investigate the model's dependence on these parameter values, we performed a sensitivity analysis by multiplying the velum stiffness or specific tension by 10 (i.e., 10.0 kPa stiffness and 0.3 MPa specific tension). The data for percentage decrease in minimum activation required were identical to the nominal results (see Figure 9a). It is interesting to note that for closure force, 10 kPa of velar stiffness (10 times nominal) combined with 0.03 MPa specific tension (nominal) significantly changed the magnitude and the ranked importance of some parameters, but VP distance remained most important for all cases (see Figure 14). The magnitudes of all parameter influences were about five times those of nominal with the stiffer velum. For instance, the closure force increases almost 80% when VP distance is decreased by 1 SD for the stiffer velum compared with 18% for the nominal velum stiffness. VP distance remained the most influential factor, followed by velum–LVP angle, velar length, LVP cross-sectional area, extravelar LVP length, VP width, origin-to-origin distance, velar thickness, and intravelar LVP length. These data suggest that if the velum is stiffer than modeled (e.g., because of increased stiffness in healthy individuals or because of the stiffening effects of scar tissue [Birch & Srodon, 2009] in individuals with repaired cleft palate), VP distance, velum–LVP angle, and velar length may be even more influential for closure force than if the velum is more compliant.

Figure 14.

Tissue parameter sensitivity analyses on closure force. Velopharyngeal (VP) distance remains most important in all cases. Increasing velar stiffness by 10 times relative to nominal while keeping specific tension at nominal value (upper right panel) increases the effects of parameter variations about five times. Moreover, velum–levator veli palatini (LVP) angle and velar length increase in relative importance to second and third most influential, respectively. CSA = cross-sectional area.

The clinical relevance of the findings from this study is the potential impact of computational modeling using MRI data in understanding surgical intervention for cleft palate repair and treatment of VP dysfunction. The use of MRI and computational modeling provides a novel method for patient-specific assessments of VP anatomy and the changes required during surgery to create normal VP function for speech. This approach could be used to decrease the overall failure rate (25%–35%; McWilliams, 1990) of primary palate repair, thus reducing the need for secondary speech surgeries (e.g., pharyngoplasties). The methods in this proposed study can provide insight into which surgical maneuvers are likely contributing to the success of one surgery procedure over another. Our results suggest that decreased VP distance may be strongly associated with proper VP function. Surgical outcome studies have shown an association of improved speech outcomes with decreased VP portal distance during phonation (Deren et al., 2005) and at rest (Pet et al., 2015). Decreasing VP distance through retropositioning and/or overlap of the LVP muscle bundles during cleft palate surgery (Pet et al., 2015; Woo, Skolnick, Sachanandani, & Grames, 2014) and by lengthening the velum through posterior displacement of the LVP muscle bundle (Furlow, 1986; Sommerlad et al., 2002) has been proposed. Also, our results suggest that velar length is very influential for closure force (if velar stiffness is increased; see Figure 14) and minimum activation required (see Figure 9a), supporting the findings that increased velar length is associated with successful Furlow rerepair procedures (D'Antonio et al., 2000). In general, surgical techniques manipulate multiple anatomical parameters simultaneously (e.g., velar length and VP distance being changed by LVP retropositioning), whereas some anatomical parameters (e.g., distance between points of origin) cannot be practically modified by surgery. Future work will model these possible simultaneous parameter changes in response to surgeries to examine the potential outcomes of various repair techniques with full consideration of patient-specific cleft palate anatomical variations.

Our model shows that increasing LVP cross-sectional area (or strength) can have a large effect on VP closure. One effective nonsurgical intervention for the treatment of VPI is continuous positive airway pressure therapy (Kuehn, Moon, & Folkins, 1993). This can be likened to resistance training for the VP muscles. Continuous positive airway pressure therapy may increase the LVP cross-sectional area (or at least LVP strength), thus improving VP closure. Overlap of the muscle during surgery (Nguyen et al., 2014; Woo et al., 2014) would also increase LVP cross-sectional area in the overlapped segment, possibly leading to increased strength and force production in that area. Other methods, such as drug therapy, that may increase LVP cross-sectional area or strength are likely to improve VP closure as well.

Future modeling studies will elucidate the effects of anatomic variations on predicted VP function in populations differing in categories such as gender and race. Our use of male subjects in this study eliminated the effect of gender, as gender has been shown to have a significant effect on VP parameters (Perry, Kuehn, Sutton, & Gamage, 2014; Perry, Kuehn, Sutton, Gamage, & Fang, 2014) and VP function (Kuehn & Moon, 1998; McKerns & Bzoch, 1970). Modeling the differences in VP morphology and function among populations in future studies may reveal the optimality of different surgical procedures for different groups.

We have shown that (a) observed anatomical variability in healthy adults results in large differences in VP closure, mirroring the high amount of observed experimental closure force variability, and (b) VP distance and LVP cross-sectional area are perhaps the most influential factors on VP closure force in healthy adults given observed variability. From these results, we conclude that interventions for VP dysfunction that decrease VP distance (e.g., autologous fat transplants, surgery with LVP overlap, retropositioning) or increase LVP cross-sectional area (e.g., via continuous positive airway pressure therapy) may be very effective in improving VP function. Furthermore, because certain anatomies are naturally less anatomically advantaged with respect to VP closure, consideration of these weaker anatomies, such as those occurring in patients with cleft palate, may influence surgery selection. Future modeling studies including more anatomical complexity to simulate normal and pathological VP function as well as surgeries will further elucidate speech mechanics and lead to improved treatment for individuals born with cleft palate.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by The Hartwell Foundation and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant 1R03DC009676-01A1. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors gratefully acknowledge useful discussions with Geoffrey Handsfield, support from Bradley P. Sutton and David P. Kuehn in the magnetic resonance imaging methods and developments, and support from Jillian Nyswonger in image analyses.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by The Hartwell Foundation and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant 1R03DC009676-01A1. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Akgüner M. (1999). Velopharyngeal anthropometric analysis with MRI in normal subjects. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 43, 142–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold E. M., Ward S. R., Lieber R. L., & Delp S. L. (2010). A model of the lower limb for analysis of human movement. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 38, 269–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzam N. A., & Kuehn D. P. (1977). The morphology of musculus uvulae. The Cleft Palate Journal, 14, 78–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae Y., Kuehn D. P., Sutton B. P., Conway C. A., & Perry J. L. (2011). Three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging of velopharyngeal structures. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 54, 1538–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer A. J., Hellerhoff P., Zimmermann A., Mady K., Sader R., Rummeny E. J., & Hannig C. (2004). Dynamic near-real-time magnetic resonance imaging for analyzing the velopharyngeal closure in comparison with videofluoroscopy. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 20, 791–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry D. A., Moon J. B., & Kuehn D. P. (1999). A finite element model of the soft palate. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 36, 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch M. J., & Srodon P. D. (2009). Biomechanical properties of the human soft palate. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 46, 268–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blemker S. S., Pinsky P. M., & Delp S. L. (2005). A 3D model of muscle reveals the causes of nonuniform strains in the biceps brachii. Journal of Biomechanics, 38, 657–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner J., Fuchs S., & Perrier P. (2009). On the relationship between palate shape and articulatory behavior. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 125, 3936–3949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S., Gandevia S. C., Green M., Sinkus R., & Bilston L. E. (2011). Viscoelastic properties of the tongue and soft palate using MR elastography. Journal of Biomechanics, 44, 450–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Antonio L. L., Eichenberg B. J., Zimmerman G. J., Patel S., Riski J. E., Herber S. C., & Hardesty R. A. (2000). Radiographic and aerodynamic measures of velopharyngeal anatomy and function following Furlow Z-plasty. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 106, 539–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deren O., Ayhan M., Tuncel A., Görgü M., Altuntas A., Kutlay R., & Erdogan B. (2005). The correction of velopharyngeal insufficiency by Furlow palatoplasty in patients older than 3 years undergoing Veau-Wardill-Kilner palatoplasty: A prospective clinical study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 116, 85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drissi C., Mitrofanoff M., Talandier C., Falip C., Le Couls V., & Adamsbaum C. (2011). Feasibility of dynamic MRI for evaluating velopharyngeal insufficiency in children. European Radiology, 21, 1462–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettema S. L., & Kuehn D. P. (1994). A quantitative histologic study of the normal human adult soft palate. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 37, 303–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettema S. L., Kuehn D. P., Perlman A. L., & Alperin N. (2002). Magnetic resonance imaging of the levator veli palatini muscle during speech. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 39, 130–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein Y., Talmi Y. P., Nachmani A., Hauben D. J., & Zohar Y. (1992). On the variability of velopharyngeal valve anatomy and function: A combined peroral and nasendoscopic study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 89, 631–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga T., Roy R. R., Shellock F. G., Hodgson J. A., & Edgerton V. R. (1996). Specific tension of human plantar flexors and dorsiflexors. Journal of Applied Physiology, 80, 158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlow L. T., Jr. (1986). Cleft palate repair by double opposing Z-plasty. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 78, 724–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon A. M., Huxley A. F., & Julian F. J. (1966). The variation in isometric tension with sarcomere length in vertebrate muscle fibres. The Journal of Physiology, 184, 170–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha S., Kuehn D. P., Cohen M., & Alperin N. (2007). Magnetic resonance imaging of the levator veli palatini muscle in speakers with repaired cleft palate. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 44, 494–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L. (1995). Mechanical modeling of palatal snoring. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 97, 3642–3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M., Lee S., & Rajendran K. (1997). Structure of the musculus uvulae: Functional and surgical implications of an anatomic study. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 34, 466–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M., Riski J., Cohen S., Simms C., & Burstein F. (1999). An anatomic evaluation of the furlow double opposing Z-plasty technique of cleft palate repair. Annals of the Academy of Medicine Singapore, 28, 672–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye J. M., Pelland K., Lin K. Y., Borowitz K. C., & Blemker S. S. (2014). A computational model of velopharyngeal closure for simulating cleft palate repair. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 26, 658–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollara L., & Perry J. L. (2013). Effects of gravity on the velopharyngeal structures in children using upright magnetic resonance imaging. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 51, 669–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollara L., Perry J. L., & Hudson S. (2014, November). Racial variations in velopharyngeal and craniometric morphology in children: Imaging study. Presentation at the Annual Convention of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Orlando, FL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn D. P., Ettema S. L., Goldwasser M. S., & Barkmeier J. C. (2004). Magnetic resonance imaging of the levator veli palatini muscle before and after primary palatoplasty. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 41, 584–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn D. P., Ettema S. L., Goldwasser M. S., Barkmeier J. C., & Wachtel J. M. (2001). Magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of occult submucous cleft palate. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 38, 421–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn D. P., & Kahane J. C. (1990). Histologic study of the normal human adult soft palate. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 27, 26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn D. P., & Moon J. B. (1998). Velopharyngeal closure force and levator veli palatini activation levels in varying phonetic contexts. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 41, 51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn D. P., Moon J. B., & Folkins J. W. (1993). Levator veli palatini muscle activity in relation to intranasal air pressure variation. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 30, 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes C. A., Weichert F., Steinbauer T., Schröder A., Walczak L., Fritsch H., & Wagner M. (2012). New details on the clefted uvular muscle: Analyzing its role at histological scale by model-based deformation analyses. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 49, 51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin M. L., Croft C. B., & Shprintzen R. J. (1980). Velopharyngeal insufficiency due to hypoplasia of the musculus uvulae and occult submucous cleft palate. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 65, 585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. S., Luo X. Y., Lee H. P., & Lu C. (2007). Snoring source identification and snoring noise prediction. Journal of Biomechanics, 40, 861–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra A., Huang Y., Fogel R. B., Pillar G., Edwards J. K., Kikinis R., … White D. P. (2002). The male predisposition to pharyngeal collapse: Importance of airway length. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 166, 1388–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKerns D., & Bzoch K. R. (1970). Variations in velopharyngeal valving: The factor of sex. The Cleft Palate Journal, 7, 652–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams B. J. (1990). The long-term speech results of primary and secondary surgical correction of palatal clefts. In Bardach J. & Morris H. L. (Eds.), Multidisciplinary management of cleft lip and palate (pp. 815–819). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Neptune R. R. (2000). Computer modeling and simulation of human movement. Applications in sport and rehabilitation. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 11, 417–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen D. C., Patel K., Skolnick G., Grames L., Stahl M., & Woo A. (2014). Progressive tightening of the levator veli palatini muscle during intravelar veloplasty improves speech results in primary palatoplasty [Abstract]. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 133(4 Suppl.), 1003. [Google Scholar]

- Nohara K., Tachimura T., & Wada T. (2006). Levator veli palatini muscle fatigue during phonation in speakers with cleft palate with borderline velopharyngeal incompetence. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 43, 103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozgür F., Tunçbilek G., & Cila A. (2000). Evaluation of velopharyngeal insufficiency with magnetic resonance imaging and nasoendoscopy. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 44, 8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. L., & Kuehn D. P. (2007). Three-dimensional computer reconstruction of the levator veli palatini muscle in situ using magnetic resonance imaging. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 44, 421–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. L., Kuehn D. P., & Sutton B. P. (2013). Morphology of the levator veli palatini muscle using magnetic resonance imaging. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 50, 64–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. L., Kuehn D. P., Sutton B. P., & Gamage J. K. (2014). Sexual dimorphism of the levator veli palatini muscle: An imaging study. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 51, 544–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. L., Kuehn D. P., Sutton B. P., Gamage J. K., & Fang X. (2014). Anthropometric analysis of the velopharynx and related craniometric dimensions in three adult populations using MRI. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. doi:10.1597/14-015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. L., Kuehn D. P., Sutton B. P., Goldwasser M. S., & Jerez A. D. (2011). Craniometric and velopharyngeal assessment of infants with and without cleft palate. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 22, 499–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. L., Sutton B. P., Kuehn D. P., & Gamage J. K. (2014). Using MRI for assessing velopharyngeal structures and function. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 51, 476–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pet M. A., Marty-Grames L., Blount-Stahl M., Saltzman B. S., Molter D. W., & Woo A. S. (2015). The Furlow palatoplasty for velopharyngeal dysfunction: Velopharyngeal changes, speech improvements, and where they intersect. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 52, 12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigott R. W., Bensen J. F., & White F. D. (1969). Nasendoscopy in the diagnosis of velo-pharyngeal incompetence. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 43, 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos V. J., & Valero-Cuevas F. J. (2006). Reported anatomical variability naturally leads to multimodal distributions of Denavit-Hartenberg parameters for the human thumb. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 53, 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott A. D., Boubertakh R., Birch M. J., & Miquel M. E. (2013). Adaptive averaging applied to dynamic imaging of the soft palate. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 70, 865–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaver E. J., & Kuehn D. P. (1980). A cineradiographic and electromyographic investigation of velar positioning in non-nasal speech. The Cleft Palate Journal, 17, 216–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommerlad B. C., Mehendale F. V., Birch M. J., Sell D., Hattee C., & Harland K. (2002). Palate re-repair revisited. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 39, 295–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srodon P. D., Miquel M. E., & Birch M. J. (2012). Finite element analysis animated simulation of velopharyngeal closure. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 49, 44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton B. P., Conway C. A., Bae Y., Seethamraju R., & Kuehn D. P. (2010). Faster dynamic imaging of speech with field inhomogeneity corrected spiral fast low angle shot (FLASH) at 3 T. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 32, 1228–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian W., & Redett R. J. (2009). New velopharyngeal measurements at rest and during speech: Implications and applications. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 20, 532–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valero-Cuevas F. J., Hoffmann H., Kurse M. U., Kutch J. J., & Theodorou E. A. (2009). Computational models for neuromuscular function. IEEE Reviews on Biomedical Engineering, 2, 110–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo A. S., Skolnick G. B., Sachanandani N. S., & Grames L. M. (2014). Evaluation of two palatal repair techniques for the surgical management of velopharyngeal insufficiency. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 134, 588e–596e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajac F. E. (1989). Muscle and tendon: Properties, models, scaling, and application to biomechanics and motor control. Critical Reviews in Biomedical Engineering, 17, 359–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]