Abstract

Purpose

Given the potential significance of speech naturalness to functional and social rehabilitation outcomes, the objective of this study was to examine the effect of listener perceptions of monopitch on speech naturalness and intelligibility in individuals with Parkinson's disease (PD).

Method

Two short utterances were extracted from monologue samples of 16 speakers with PD and 5 age-matched adults without PD. Sixteen listeners evaluated these stimuli for monopitch, speech naturalness and intelligibility using the visual sort and rate method.

Results

Naïve listeners can reliably judge monopitch, speech naturalness, and intelligibility with minimal familiarization. While monopitch and speech intelligibility were only moderately correlated, monopitch and speech naturalness were highly correlated.

Conclusions

A great deal of attention is currently being paid to improvement of vocal loudness and thus speech intelligibility in PD. Our findings suggest that prosodic characteristics such as monopitch should be explored as adjuncts to this treatment of dysarthria in PD. Development of such prosodic treatments may enhance speech naturalness and thus improve quality of life.

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a slowly progressing neurodegenerative condition that affects approximately 1%–2% of the population aged over 65 years and 3%–5% of the population over 85 years (Fahn, 2003). Although individuals with PD commonly present with cardinal motor deficits, such as tremor, rigidity, akinesia/bradykinesia, and postural instability, more than 90% of individuals with PD develop various speech deficits, such as reduced loudness, impaired articulation, and abnormal prosody (i.e., dysprosody) that collectively affect intelligibility of speech (Logemann, Fisher, Boshes, & Blonsky, 1978). Intelligibility can be defined as “the degree to which a speaker's message can be recovered by a listener” (Kent, Weismer, Kent, & Rosenbek, 1989, p. 483). Dysprosody is a well-known and common speech deficit associated with PD (Caekebeke, Jennekens-Schinkel, Van der Linden, Buruma, & Roos, 1991). It can include disturbances in variation of fundamental frequency (f0; Gamboa et al., 1997; Goberman, Coelho, & Robb, 2002; Holmes, Oates, Phyland, & Hughes, 2000; Jiménez-Jiménez et al., 1997; Metter & Hanson, 1986; Skodda, Rinsche, & Schlegel, 2009) commonly perceived as monopitch, disturbances in variation of intensity (Metter & Hanson, 1986) commonly perceived as monoloudness, and disturbances in variation of stress (Cheang & Pell, 2007; Pell, Cheang, & Leonard, 2006). Previous research has demonstrated that monopitch is the most deviated perceptual dimension in PD speech (Darley, Aronson, & Brown, 1969; Holmes et al., 2000; Ludlow & Bassich, 1984; Plowman-Prine et al., 2009). Despite this widespread agreement on the occurrence of prosodic impairments in individuals with PD, little progress has been made toward assessment and treatment of prosodic impairments. This lack of attention may be related to the complexity of the analysis of prosodic impairments. For instance, no clear consensus exists on perceptual, acoustic, or linguistic classifications, and speech stimuli that are most sensitive to prosodic disturbances (e.g., conversations) have more complex structures.

These prosodic deficits, such as monopitch, are also closely related to the concept of the naturalness of speech. Speech naturalness can be described as how the speech of a person with a speech disorder compares with that of typical speech or, in the case of an acquired disorder, how an individual's speech compares to its premorbid state. Speech is natural “if it conforms to the listener's standards of rate, rhythm, intonation, stress patterning, and if it conforms to the syntactic structure of the utterance being produced” (Yorkston, Beukelman, Strand, & Bell, 1999, p. 464). Studies examining listener impressions of speech reveal that individuals with PD are often perceived to be significantly unhappy, cold, withdrawn, introverted, and bored compared with controls (Jaywant & Pell, 2010; Pitcairn, Clemie, Gray, & Pentland, 1990). Recent research also suggests that individuals with PD perceive a negative impact on their communication, which is accompanied by feelings of social isolation (Miller, Noble, Jones, Allcock, & Burn, 2008). It is highly likely that such self-perceived and/or listener-perceived changes could be related to naturalness of speech. It is important to note that such reductions in naturalness could occur before any apparent decline in intelligibility or referral to speech-language pathologists (Miller, Noble, Jones, & Burn, 2006). Speech naturalness has been investigated as an outcome measure in disorders such as stuttering (Metz, Schiavetti, & Sacco, 1990; Teshima, Langevin, Hagler, & Kully, 2010) and alaryngeal speech (Eadie & Doyle, 2002), yet it has received very little attention in individuals with dysarthria (Dagenais, Brown, & Moore, 2006; Whitehill, Ciocca, & Yiu, 2004). Although there is an established relationship between speech naturalness and monopitch in electrolaryngeal and synthetically monotonized laryngeal speech (Meltzner & Hillman, 2005), to our knowledge, no study has precisely explored the relationship between these two entities in PD.

Over the past several decades, improvement of speech intelligibility in individuals with PD has been a matter of foremost concern among speech therapy approaches. Such approaches can be categorized into those that use biofeedback (e.g., speech intensity; Rubow & Swift, 1985); devices (e.g., voice amplifiers; Greene & Watson, 1968); masking (Adams & Lang, 1992; Ho, Bradshaw, Iansek, & Alfredson, 1999; Stathopoulos et al., 2014); behavioral voice treatments, such as rate reduction (Duffy, 1995; Lowit, Dobinson, Timmins, Howell, & Kröger, 2010); delayed auditory feedback (Hanson & Metter, 1983); clear speech (Goberman & Elmer, 2005); targeted respiratory exercises (Baumgartner, Sapir, & Ramig, 2001; Ramig, Countryman, Thompson, & Horii, 1995); and Lee-Silverman Voice Treatment (Ramig, Bonitati, Lemke, & Horii, 1994; Ramig, Fox, & Sapir, 2004, 2008). A large number of studies have reported overall improvements in speech intensity, voice quality, articulation, and speech intelligibility (Baumgartner et al., 2001; Cannito et al., 2012; Fox et al., 2006; Ramig et al., 1994, 1995, 2001; Sapir, Spielman, Ramig, Story, & Fox, 2007; Trail et al., 2005), but the effects of these treatments on speech naturalness has not been investigated. For example, although the rate reduction technique provides significant improvements in intelligibility, it is arguable that a slow rate of speech could affect how natural an individual might sound in his or her everyday life (Patel, Connaghan, & Campellone, 2013). Prosodic improvements are typically not tracked in the current treatment methods, and increasing speech intensity (the most common PD treatment goal) may not necessarily transfer to improvements in prosodic variations. It is important to note that anecdotal reports have shown that prosody-based treatment approaches hold the most promise for improving speech intelligibility as well as naturalness (Liss, 2007). One of the earliest studies by Scott and Caird (1983) reported significant improvements in 26 patients with PD when they received daily speech therapy that focused on prosodic exercises for 2 to 3 weeks. Therefore, directed treatments to aspects such as prosody and their effects on speech naturalness are needed.

Speech naturalness may be a useful functional outcome measure of the effects of PD on individuals' communication for two primary reasons. First, although articulatory disturbances predominantly affect judgments of speech intelligibility, prosodic deficits, such as monopitch, arguably affect judgments of speech naturalness to a greater extent (Kent & Rosenbek, 1982; Yorkston et al., 1999). For example, De Bodt, Hernández-Dí́az Huici, and Van De Heyning (2002) found that articulation was highly correlated with intelligibility (r = .82) rather than prosody (r = .55). Plowman-Prine et al. (2009) also confirmed this argument, finding that articulatory imprecisions were highly correlated to judgments of speech intelligibility (r s = .81, p < .01) and that the perception of monopitch and intelligibility were only moderately correlated (r s = .48, p < .01). Therefore, there is reason to believe that prosodic abnormalities, such as monopitch, may significantly limit an individual's ability to communicate in a natural manner even in the presence of largely preserved intelligibility (Yorkston, Miller, & Strand, 2004). Second, speech characterized by monopitch and reduced naturalness can specifically translate to decreases in participation: “taking part in life situations where knowledge, information, ideas or feelings are exchanged” (Eadie et al., 2006, p. 309). When communication deficits interfere with participation in life roles, negative consequences, such as loss of employment or difficulty pursuing services (for example, health care) may follow. Thus, reduced naturalness can cause loss of independence affecting individuals' participation at the society level and thus their quality of life (Miller et al., 2006, 2008; Pell et al., 2006).

In general, studies of fundamental frequency (f0) variability in PD have found nonexistent (Holmes et al., 2000; Ludlow & Bassich, 1984) or very small effects (Adams, Reyno-Briscoe, & Hutchinson, 1998; Bowen, Hands, Pradhan, & Stepp, 2014; Gamboa et al., 1997; Jiménez-Jiménez et al., 1997; Skodda, Grönheit, & Schlegel, 2011). Findings related to f0 variability may be equivocal because the acoustic measure (f0SD) in a connected speech sample may reflect the use of intonation for many communicative functions without clearly identifying the contribution of any single aspect (for example, at specific syntactic boundaries or to mark stress) to perception of monopitch (MacPherson, Huber, & Snow, 2011). Thus, f0 variability may be a correlate, albeit a poor one. Hence, examination of monopitch in PD must rely on carefully conducted listener judgments until a valid acoustic correlate can be identified. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to examine effects of listener perception of monopitch on speech naturalness and compare it to intelligibility. It was hypothesized that judgments of monopitch would explain a significant portion of the variance in judgments of naturalness but only a moderate amount of the variance in judgments of intelligibility.

Understanding the effects of monopitch on speech naturalness will provide specific therapeutic targets to enhance prosodic proficiency and consequently improve speech naturalness and communicative effectiveness in a greater number of individuals with PD. Even small changes in remediating prosodic abnormalities, such as monopitch and speech naturalness, may be associated with substantial improvement in social communication, for example, in the patient's self-confidence in his or her ability to use telephone, and subsequently the level of independence achieved. Speech naturalness is a combination of all prosodic dimensions, such as monopitch, monoloudness, and stress. In this study, we focused on the effects of monopitch on speech naturalness because prior perceptual studies suggest that this dimension has been highly ranked compared with others (Darley et al., 1969). Further, as evidenced by the literature, studies of monoloudness and intensity variation in PD do not appear to be as comprehensive or conclusive as that of monopitch and f0 variability. Results of this study may facilitate future work utilizing novel f0 variability measures and prosodic dimensions through acoustic-perceptual studies.

Method

All the individuals completed informed consent either through the University of Washington Institutional Review Board or through the Boston University Institutional Review Board. All participants received compensation for their time.

Speakers

Speakers for perceptual testing were chosen from a speech database of 75 older adults diagnosed with idiopathic PD by a movement disorders specialist and 45 older adults without PD. These recordings included 45- to 90-s monologue samples, and therefore, samples were different for each speaker. The first author (S.A.) and a speech-language pathology undergraduate student who was trained by the first author selected 16 speakers with PD aged 41–82 years (12 men and four women) from this database, grouped under each of the following categories: (a) high naturalness and high intelligibility, (b) high naturalness and low intelligibility, (c) low naturalness and high intelligibility, and (d) low naturalness and low intelligibility, to represent a continuum of speech naturalness and intelligibility. The mean age for male and female speakers with PD was 66 (SD = 11.18) and 74 (SD = 6.45) years, respectively. The disease duration since time of diagnosis ranged from 1 to 17 years (M = 9.00; SD = 5.92). In addition, the first author judged severity of dysarthria on a 3-point scale (1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe). About half of the speakers with PD (50%) were judged to be mild in severity, 25% were judged to be moderate, and the remaining 25% to be severe. It was also ensured that all the chosen recordings were consistent with regard to medication status (“ON”). Speech stimuli from five male controls aged 51–74 years (M = 61.00; SD = 9.26) were also selected with high naturalness and high intelligibility to represent a continuum. None of the speakers had reported any neurological, speech, or language disorders other than PD; a fraction had reported some minor age-related hearing loss. Demographic characteristics of the speakers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Speaker demographics.

| S. No | Group | Age | Sex | Disease duration (years) | Dysarthria severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | PD | 58 | M | 16 | Severe |

| 2. | PD | 81 | M | 2 | Moderate |

| 3. | PD | 68 | F | 17 | Mild |

| 4. | PD | 73 | M | 10 | Severe |

| 5. | PD | 69 | M | 9 | Severe |

| 6. | PD | 70 | M | 1.5 | Mild |

| 7. | PD | 78 | M | 8 | Severe |

| 8. | PD | 57 | M | 15 | Mild |

| 9. | PD | 82 | F | 16 | Moderate |

| 10. | PD | 41 | M | 2 | Mild |

| 11. | PD | 74 | M | 9 | Moderate |

| 12. | PD | 69 | M | 5 | Mild |

| 13. | PD | 70 | F | 1 | Mild |

| 14. | PD | 61 | M | 10 | Mild |

| 15. | PD | 77 | F | 16 | Moderate |

| 16. | PD | 58 | M | 2.5 | Mild |

| 17. | HC | 66 | M | ||

| 18. | HC | 56 | M | ||

| 19. | HC | 51 | M | ||

| 20. | HC | 56 | M | ||

| 21. | HC | 74 | M |

Note. PD = individuals with Parkinson's disease; HC = healthy controls; M = male; F = female.

Speech Stimuli

Two utterances were extracted from the monologue samples, resulting in a total of 42 stimuli (21 speakers × two utterances). Inclusionary criteria for the utterance selections were absence of obvious misarticulation that would impair intelligibility judgments, absence of extreme emotional or linguistic content that would affect monopitch judgments, and absence of long pauses or hesitations exhibited by stuttering-like behavior that would influence naturalness judgments. The first author heard the speech stimuli multiple times to ensure that the chosen monologue samples were representative of the speaker's natural speech pattern. The selected speech stimuli were edited to be of approximately 2 s each in Audacity software (version 2.0.5), and each utterance consisted of one to two complete sentences, similar to previous studies (Nagle & Eadie, 2012; Spielman, Ramig, Mahler, Halpern, & Gavin, 2007; Tjaden & Wilding, 2004; Weismer & Laures, 2002). All stimuli were amplitude normalized, and speech-shaped noise was added for judgments of intelligibility. The addition of noise to speech samples served as a method to (a) produce more realistic daily-life listening conditions and (b) to reduce ceiling effects in listener ratings of intelligibility. Speech-shaped noise was created such that the signal-to-noise ratio was −4 dB consistent with prior studies (Bunton, Kent, Kent, & Duffy, 2001; Laures & Weismer, 1999). For the purposes of intralistener reliability, 15% of the total stimuli were repeated during the listening session. Thus, listeners provided ratings of monopitch, speech naturalness, and speech intelligibility for a total of 48 stimuli.

Listeners

Sixteen listeners aged 18–27 years (10 women and six men) provided ratings of monopitch, speech naturalness, and speech intelligibility. All listeners were native speakers of American English and did not have any speech-language pathology background. Although a formal hearing screening was not conducted, a self-report from listeners revealed that they all had normal hearing abilities.

Experimental Procedure

Prior to the acquisition of ratings, listeners were first familiarized with descriptions of naturalness and intelligibility. Speech naturalness was described as how the speech of a person with a speech disorder compares with that of nondisordered speech or, in the case of an acquired disorder, how an individual's speech compares to its premorbid state as well as if it conforms to the listener's standards of rate, rhythm, intonation, and stress patterning and if it conforms to the syntactic structure of the utterance being produced. Speech intelligibility was described as the degree to which speech is understood. Monopitch was operationally defined as voice that lacks normal pitch and inflectional changes, tending to stay at one pitch level. All the stimuli were presented using headphones (Sennheiser HD280 PRO) in a sound-treated room. There was not a set dB level used across listeners. Listeners could change the computer volume level. This method was specifically followed to accommodate the different hearing comfort levels for the intelligibility judgments given the presence of noise in stimuli.

All the stimuli were presented in three blocks, each consisting of four sets of 12 stimuli. In the first block, listeners made judgments of speech intelligibility. Intelligibility was judged first to avoid familiarization effects. The second and third blocks required listeners to make judgments of speech naturalness and then monopitch. Listeners were given a short familiarization task prior to making judgments of monopitch to confirm that they could identify pitch variability within an utterance. Six different stimuli were chosen to represent a continuum of pitch variability, and listeners heard these samples as many times as they required. The total duration of the listening session was approximately 2 hr per listener, including breaks.

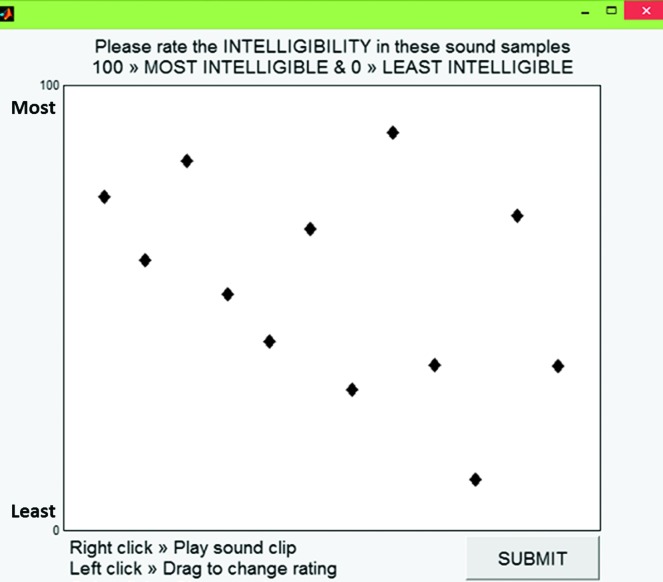

Visual Sort and Rate Method

Listeners provided ratings using the visual sort and rank method (Granqvist, 2003) using a custom-designed user interface developed in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA). Listeners listened to each stimulus by clicking on each of the markers (see Figure 1). First, listeners sorted all stimuli such that stimuli perceived to be highly natural or intelligible or had adequate pitch variability were placed higher on the screen by varying the height of a horizontal line on the interface using a mouse. Second, they assigned specific ratings on a scale between 0 and 100 that represented two ends of the continuum, for instance, 0 = least natural, 100 = highly natural. Listeners were encouraged to listen to all sound samples from low–high or high–low continuums to ensure they were satisfied with their ratings. One of the main advantages of this method is that it facilitates comparison of each stimulus with one other—that is, each stimulus serves as an external reference for all other stimuli rather than an internal reference that is commonly used in other perceptual rating methods. In this visual sort and rank task, 48 stimuli were presented in four sets of 12 stimuli each to reduce listener fatigue and allow easy comparison. Four listeners provided pilot ratings of the three percepts; then sets were arranged so that the distribution of the stimuli in each set were representative of the distribution of the entire data set. Stimuli were also randomized within and between sets for each listener.

Figure 1.

An illustration of the graphical user interface used for the collection of perceptual judgments. Each of the diamond markers represents a sound clip.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (Version 20) and an alpha level of 0.05 was used for significance testing. Perceived judgments were averaged between the two utterances that were selected from each speaker. Inter- and intralistener reliability for mean ratings of monopitch, speech naturalness, and intelligibility were determined by computing Pearson product–moment correlation coefficients (r). Regression analysis was performed to evaluate the amount of variance (coefficient of determination, expressed as R 2) explained by monopitch on perceptual judgments of speech naturalness and intelligibility. In addition, the relationship between judgments of speech naturalness and intelligibility was also investigated using Pearson's r. The relationship between disease duration in speakers with PD and these speech percepts was also examined using correlation analysis. Given the limited sample size, a visual analysis of the relationship between dysarthria severity and perceptual dimensions was performed.

Results

Reliability Analysis

Perceptual judgments of monopitch, speech naturalness, and intelligibility of 15% of repeated samples (N = 6) were used for computing intralistener reliability. Because the listeners in this experiment had no previous experience in assessing dysarthric speech samples, we set a specific criteria of Pearson's r ≥ 0.65 to ascertain that they were consistent. This criterion was chosen in accordance with reliability thresholds of dysarthric speech ratings from prior literature (Plowman-Prine et al., 2009). In accordance with this criterion, we eliminated four listeners (two women and two men) from further analyses. The mean intralistener reliability for monopitch, speech naturalness, and intelligibility judgments pre- and postlistener exclusion is presented in Table 2. To determine the interlistener reliability, pairwise Pearson's correlation coefficients were computed for the average judgments of monopitch, speech naturalness, and intelligibility for each stimulus across all pairs of listeners. These were then averaged to obtain the mean interlistener reliability. The mean interlistener reliability for intelligibility judgments was 0.70 (SD = 0.15). The interlistener reliability for speech naturalness and monopitch judgments were 0.81 (SD = 0.14) and 0.65 (SD = 0.18), respectively.

Table 2.

Mean intralistener reliability for judgments of monopitch, speech naturalness, and intelligibility without (center column, N = 16) and with (right column, N = 12) exclusion on the basis of criterion.

| Judgments | Pearson's r (SD) | Pearson's r (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Monopitch | 0.83 (0.16) | 0.91 (0.07) |

| Speech naturalness | 0.93 (0.08) | 0.94 (0.05) |

| Speech intelligibility | 0.88 (0.09) | 0.91 (0.06) |

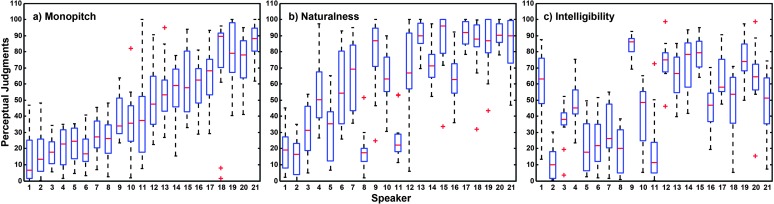

Mean Perceptual Judgments

Perceptual judgments of monopitch, speech naturalness, and intelligibility for all experimental stimuli are shown in Figures 2a–2c, respectively. On the abscissa, speaker order has been maintained for all the subplots. Values near 0 correspond to low pitch variability (monopitch), naturalness, or intelligibility, and values near 100 correspond to high pitch variability, naturalness, or intelligibility on the ordinate. It is evident that judgments for the 21 speakers covered a broad continuum of perceived monopitch with judgments ranging from 14.52 to 86.72. Likewise, perceived speech naturalness and intelligibility ranged from 15.51 to 91.46 and 10.90 to 83.84, respectively.

Figure 2.

Perceptual judgments across 21 speakers. Subplots represent (a) Perceived monopitch, (b) perceived speech naturalness, and (c) perceived speech intelligibility. Each of the speakers are shown on the abscissa and ordered from low to high perceived pitch variability. The same order of speakers is maintained for subplots (b) and (c). Box plots based on results from the 12 listeners show the median, 25th, and 75th percentile, SD, and outliers.

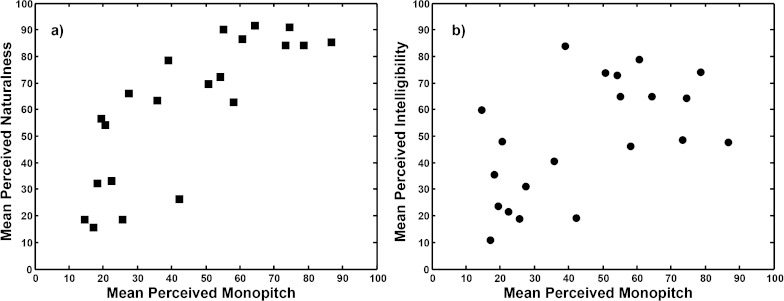

Relationship Between Judgments

Figures 3a and 3b display mean perceived naturalness and intelligibility judgments as a function of perceived monopitch judgments, respectively. Again, values near 0 correspond to low pitch variability (monopitch), naturalness, or intelligibility, and values near 100 correspond to high pitch variability, naturalness, or intelligibility. It is evident from the figure that perceived monopitch is strongly related to perceived naturalness. Confirming our hypothesis, a linear regression analysis revealed that, while 64% of the variance in perceived naturalness judgments was explained by perceived monopitch judgments, only 31% of the variance in perceived intelligibility judgments was explained by perceived monopitch judgments. However, the relationship between perceived speech naturalness and intelligibility was significant (r = .720, p < .001).

Figure 3.

Mean perceived (a) speech naturalness and (b) speech intelligibility plotted as a function of perceived monopitch. Values closer to 0 reflect greater monopitch (low pitch variability), and values closer to 100 reflect less monopitch (high pitch variability). Symbols or markers represent judgments averaged across 12 listeners.

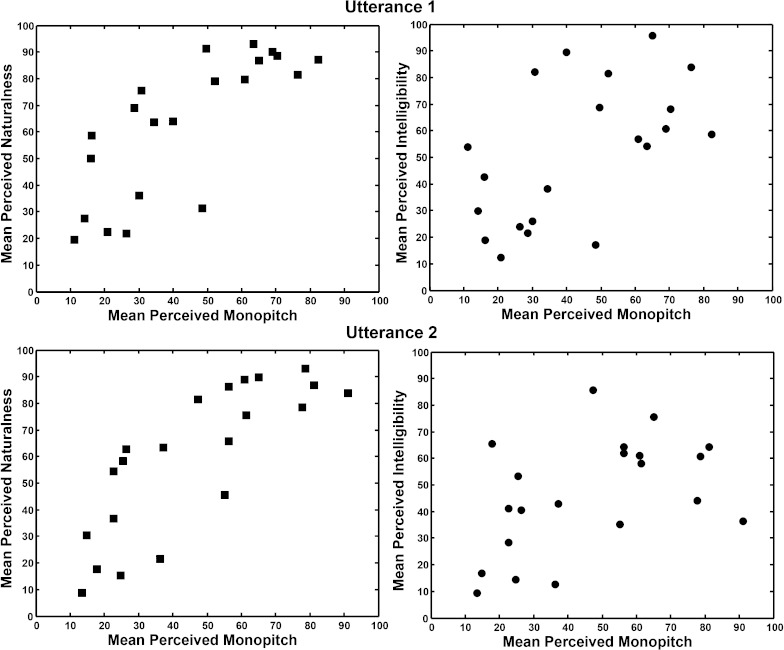

Utterance Effect

For all the previous analyses, perceived judgments were averaged between the two utterances that were selected from each speaker to get an overall judgment of the intelligibility, naturalness, and monopitch of the speaker. It is likely that each utterance was produced in a different manner, and hence, we performed individual regression analyses for each of the utterances to determine if specific utterances had an impact on different judgments. These findings, as depicted in Figure 4, revealed that the overall relationships followed the same trend as averaged perceptual judgments. The correlation between mean perceived monopitch and perceived naturalness was again strong for each utterance (Pearson's r = .774; p < .001 and r = .806; p < .001). The correlation between mean perceived monopitch and perceived intelligibility was moderate for each utterance (Pearson's r = .570; p < .010 and r = .474; p < .050). Results from linear regression analysis revealed perceived monopitch accounts for 60% of the variance in perceived naturalness for Utterance 1 and 65% of the variance in perceived naturalness for Utterance 2. Similarly, analysis revealed that only 33% and 22% of the variance in perceived intelligibility was explained by perceived monopitch judgments for Utterances 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 4.

Mean perceived speech naturalness (left) and speech intelligibility (right) plotted as a function of perceived monopitch. Values closer to 0 reflect greater monopitch (low pitch variability), and values closer to 100 reflect less monopitch (high pitch variability). Top row represents judgments for utterance 1, and bottom row represents judgments for utterance 2. Symbols or markers represent judgments averaged across 12 listeners.

Relationship Between Disease Duration and Mean Perceptual Judgments

Disease duration showed a significant negative correlation to only mean perceived monopitch (Pearson's r = −.505, p < .050). Although the correlation between disease duration and other two speech percepts (speech naturalness and intelligibility) did not achieve significance, trends revealed that they were moderately correlated (also in the negative direction). Thus, as the disease duration progressed in individuals with PD, their speech was perceived to be less natural, less intelligible, and to have low pitch variability or monopitch.

Relationship Between Dysarthria Severity and Mean Perceptual Judgments

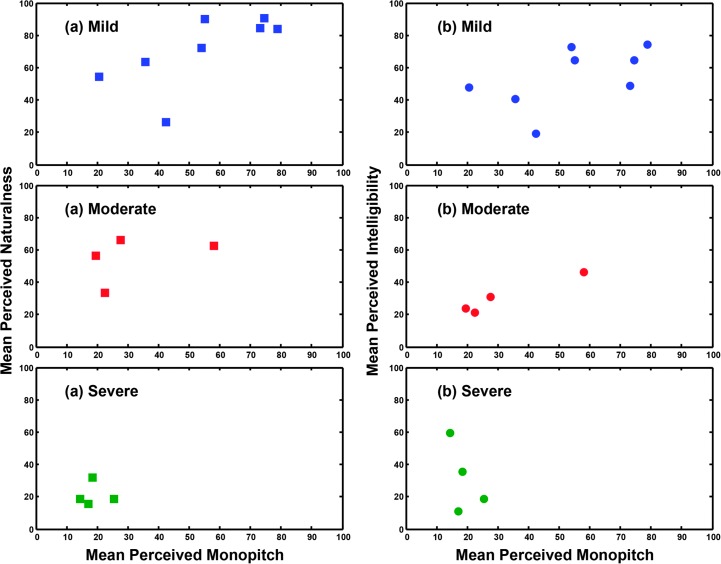

Figure 5 depicts mean perceived naturalness (left column) and intelligibility (right column) judgments as a function of perceived monopitch judgments in speakers with PD only. The rows reflect the degree of dysarthria severity (top = mild; center = moderate; bottom = severe). Values near 0 correspond to low pitch variability (monopitch), naturalness, or intelligibility, and values near 100 correspond to high pitch variability, naturalness, or intelligibility. Visual inspection revealed that speakers with PD with mild severity received a wider range of perceptual ratings compared with other degrees of severity. Within the group of mild dysarthric speakers with PD, while monopitch appeared highly related to speech naturalness, it was only moderately related to intelligibility. For severely dysarthric speakers with PD, monopitch seemed moderately related to speech naturalness and poorly related to intelligibility. On the other hand, for individuals with moderate dysarthria, monopitch seemed highly related to speech intelligibility and only moderately related to naturalness.

Figure 5.

Mean perceived speech naturalness (left column) and speech intelligibility (right column) plotted as a function of perceived monopitch for PD speakers. Each row represents the overall degree of dysarthria severity (top = mild; center = moderate; bottom = severe). On the x-axis, values closer to 0 reflect greater monopitch (low pitch variability), and values closer to 100 reflect less monopitch (high pitch variability).

Discussion

The current study was designed to explore the potential relationship between perception of monopitch and speech naturalness in individuals with PD and compare it to speech intelligibility. Although there have been some opposing findings regarding the role of listener experience (naïve vs. expert) in the assessment of dysarthric speech (Bunton, Kent, Duffy, Rosenbek, & Kent, 2007; Dagenais, Watts, Turnage, & Kennedy, 1999), our findings demonstrate that naïve listeners are capable of judging PD speech, specifically characteristics of monopitch, speech naturalness, and intelligibility, in a reliable manner. Both intra- and interlistener reliability values in this study are higher when compared with a previous study by Plowman-Prine et al. (2009) in which three expert listeners (speech-language pathologists with an average of 9 years of experience) demonstrated mean intralistener reliability of 0.84 and mean interlistener reliability of 0.65. In addition, our listener judgments spanned a wide range of perceived values, affirming our range of stimuli selection (four listeners were excluded due to mediocre intralistener reliability with r < .65). Naïve listeners with no experience in judging a speech-disordered population were selected in the present study to represent perception of communication partners of individuals with PD in their everyday life. Our findings are encouraging because, with minimum familiarization, listeners were able to judge dysarthric speech characteristics, and their reliability values were comparable to experts and existing dysarthric literature on other speech dimensions.

Prior research suggests that listeners' perception of intelligibility is highly correlated with the perception of other dimensions, such as bizarreness, naturalness, and acceptability (Dagenais et al., 1999; Southwood & Weismer, 1993). Our results agree, showing a significant correlation between perceived speech intelligibility and naturalness. However, although related, there were differences between these two perceptual dimensions, confirming our initial hypotheses. Overall findings as well as individual utterance analysis indicated that the contribution of perceived monopitch toward naturalness judgments was almost twice that of intelligibility. These findings are analogous to earlier perceptual studies in which monopitch was only moderately correlated to speech intelligibility in comparison to high correlations between articulatory impairments to speech intelligibility.

On the basis of visual inspection, even though disease duration was not significantly correlated with all of the speech percepts, general trends indicated that there was a decline in pitch variability, speech naturalness, and intelligibility. It is interesting to note that the relationship between these perceptual dimensions (monopitch, speech naturalness, and intelligibility) changed on the basis of the severity of dysarthria. For speakers with PD in the mild and severe categories, monopitch seemed highly related to naturalness compared with speech intelligibility. These results are analogous to the overall trends. On the contrary, for speakers with PD in the moderate category, monopitch seemed more related to speech intelligibility than speech naturalness. This could suggest that listeners agreed on end points of the scale—that is, what constituted as least or most natural or intelligible—but were variable specifically in their judgments of speech naturalness for speakers in the middle or with moderate dysarthria severity. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution due to limited sample size (N = 4 in the moderate and severe dysarthria categories).

To determine if any of our speakers with PD demonstrated declines in speech naturalness but not intelligibility, we examined the perceptual judgments for each speaker. Among the 16 speakers with PD, one received a relatively high mean intelligibility rating of 59.7 and a naturalness rating of only 18.6. Mean perceived monopitch rating for this speaker was 14.5. Although only evident in one of our speakers with PD, this finding suggests that self-perceived or listener-perceived changes in speech (e.g., speech naturalness) could occur before the decline in speech intelligibility and that monopitch could be a contributing factor. Speech characterized by monopitch could lead to a reduction in perceived naturalness of speech and often be misinterpreted by communication partners as an indicator of a possible lack of interest on the part of the speaker and/or affective disorders, such as depression (Aronson, 1990). Thus, loss of speech naturalness can lead to a variety of psychosocial sequelae in PD and specifically affect participation at the societal level as recently highlighted by the World Health Organization (2006).

Although the current findings show promising trends, certain limitations must be highlighted. A small sample of both speakers with PD and listeners were assessed compared with other perceptual studies. To be more specific, a limited number of female speakers with PD limits the generalizability of these conclusions. In addition, we did not have equal representation of dysarthria severity. Our goal was to determine if listener perceptions of monopitch, speech naturalness, and intelligibility exist in the first place and how they are related to each other. The present study was not intended to identify the difference between listener perceptions for speakers with PD and controls. A larger study with more controls who also vary along a continuum will give us more information on group differences. These limitations provide directions for important future work in this area. A logical extension of this study will be to examine listener perceptions of other prosodic characteristics, such as monoloudness and reduced stress. Systematic analyses of speech naturalness should be conducted by experimentally manipulating these individual prosodic components.

In summary, to our knowledge, this study provides the first confirmation of the relationships between monopitch, speech naturalness, and speech intelligibility in individuals with PD. Monopitch is highly correlated to speech naturalness. Findings also point to further exploration of contributions of other prosodic dimensions toward speech naturalness. Current rehabilitative programs for improving communication in individuals with PD largely emphasize increasing speech intelligibility (primarily through increasing loudness) in keeping with the tradition of functional communicative goals. Although these programs may be efficacious for some speakers with PD, these findings suggest that some patients may benefit from alternative approaches. To be specific, the discrepancy between contributions of perceived monopitch toward perceived naturalness versus intelligibility calls into question the validity of using only intelligibility for planning therapeutic intervention, especially in individuals with PD whose intelligibility is not severely degraded. Last, careful examination of acoustic–perceptual relationships of speech naturalness using novel acoustic measures of different prosodic dimensions could provide much-needed objective measures to evaluate treatment outcomes. Speech naturalness translates to individual's participation at the societal level. Thus, from a rehabilitation perspective, exploring speech naturalness and communicative participation using both perceptual and acoustic measures of prosody is an important clinical endeavor.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant DC012651 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (awarded to C. E. Stepp), and the Boston Rehabilitation Outcomes Center was supported by Grant HD065688 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (awarded to A. M. Jette). The authors wish to thank Jessica Malloy for assistance with participant recruitment and the four listeners who provided pilot ratings of the three percepts.

This work was completed by the first author, Supraja Anand, as part of postdoctoral training at Boston University under the mentorship of the second author, Dr. Cara E. Stepp.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Grant DC012651 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (awarded to C. E. Stepp), and the Boston Rehabilitation Outcomes Center was supported by Grant HD065688 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (awarded to A. M. Jette).

References

- Adams S. G., & Lang A. E. (1992). Can the Lombard effect be used to improve low voice intensity in Parkinson's disease? International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 27, 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams S. G., Reyno-Briscoe K., & Hutchinson L. (1998). Acoustic correlates of monotone speech in Parkinson's disease. Canadian Acoustics, 26(3), 86–87. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson A. E. (1990). Clinical voice disorders: An interdisciplinary approach. New York, NY: Thieme. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner C. A., Sapir S., & Ramig L. O. (2001). Voice quality changes following phonatory-respiratory effort treatment (LSVT®) versus respiratory effort treatment for individuals with Parkinson disease. Journal of Voice, 15, 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen L. K., Hands G. L., Pradhan S., & Stepp C. E. (2014). Effects of Parkinson's disease on fundamental frequency variability in running speech. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 21, 235–244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunton K., Kent R. D., Duffy J. R., Rosenbek J. C., & Kent J. F. (2007). Listener agreement for auditory-perceptual ratings of dysarthria. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50, 1481–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunton K., Kent R. D., Kent J. F., & Duffy J. R. (2001). The effects of flattening fundamental frequency contours on sentence intelligibility in speakers with dysarthria. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 15, 181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Caekebeke J., Jennekens-Schinkel A., Van der Linden M., Buruma O., & Roos R. (1991). The interpretation of dysprosody in patients with Parkinson's disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, & Psychiatry, 54, 145–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannito M. P., Suiter D. M., Beverly D., Chorna L., Wolf T., & Pfeiffer R. M. (2012). Sentence intelligibility before and after voice treatment in speakers with idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Journal of Voice, 26, 214–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheang H. S., & Pell M. D. (2007). An acoustic investigation of Parkinsonian speech in linguistic and emotional contexts. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 20, 221–241. [Google Scholar]

- Dagenais P. A., Brown G. R., & Moore R. E. (2006). Speech rate effects upon intelligibility and acceptability of dysarthric speech. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 20, 141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagenais P. A., Watts C., Turnage L., & Kennedy S. (1999). Intelligibility and acceptability of moderately dysarthric speech by three types of listeners. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 7, 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Darley F. L., Aronson A. E., & Brown J. R. (1969). Differential diagnostic patterns of dysarthria. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 12, 246–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bodt M. S., Hernández-Dí́az Huici M. E., & Van De Heyning P. H. (2002). Intelligibility as a linear combination of dimensions in dysarthric speech. Journal of Communication Disorders, 35, 283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy J. R. (1995). Motor speech disorders: Substrates, differential diagnosis, and management. St. Louis, MO: Mosby. [Google Scholar]

- Eadie T. L., & Doyle P. C. (2002). Direct magnitude estimation and interval scaling of naturalness and severity in tracheoesophageal (TE) speakers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 45, 1088–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eadie T. L., Yorkston K. M., Klasner E. R., Dudgeon B. J., Deitz J. C., Baylor C. R., … Amtmann D. (2006). Measuring communicative participation: A review of self-report instruments in speech-language pathology. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15, 307–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahn S. (2003). Description of Parkinson's disease as a clinical syndrome. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 991, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox C. M., Ramig L. O., Ciucci M. R., Sapir S., McFarland D. H., & Farley B. G. (2006). The science and practice of LSVT/LOUD: Neural plasticity-principled approach to treating individuals with Parkinson disease and other neurological disorders. Seminars in Speech and Language, 27, 283–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamboa J., Jiménez-Jiménez F. J., Nieto A., Montojo J., Ortí-Pareja M., Molina J. A., … Cobeta I. (1997). Acoustic voice analysis in patients with Parkinson's disease treated with dopaminergic drugs. Journal of Voice, 11, 314–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goberman A. M., Coelho C., & Robb M. (2002). Phonatory characteristics of Parkinsonian speech before and after morning medication: The ON and OFF states. Journal of Communication Disorders, 35, 217–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goberman A. M., & Elmer L. W. (2005). Acoustic analysis of clear versus conversational speech in individuals with Parkinson disease. Journal of Communication Disorders, 38, 215–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granqvist S. (2003). The visual sort and rate method for perceptual evaluation in listening tests. Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocology, 28, 109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene M., & Watson B. (1968). The value of speech amplification in Parkinson's disease patients. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 20, 250–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson W. R., & Metter E. J. (1983). DAF speech rate modification in Parkinson's disease: A report of two cases. In Berry W. R. (Ed.), Clinical dysarthria (pp. 231–251). San Diego, CA: College-Hill Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ho A. K., Bradshaw J. L., Iansek R., & Alfredson R. (1999). Speech volume regulation in Parkinson's disease: Effects of implicit cues and explicit instructions. Neuropsychologia, 37, 1453–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes R. J., Oates J. M., Phyland D. J., & Hughes A. J. (2000). Voice characteristics in the progression of Parkinson's disease. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 35, 407–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaywant A., & Pell M. D. (2010). Listener impressions of speakers with Parkinson's disease. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 16, 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Jiménez F. J., Gamboa J., Nieto A., Guerrero J., Orti-Pareja M., Molina J. A., … Cobeta I. (1997). Acoustic voice analysis in untreated patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 3, 111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent R. D., & Rosenbek J. C. (1982). Prosodic disturbance and neurologic lesion. Brain and Language, 15, 259–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent R. D., Weismer G., Kent J. F., & Rosenbek J. C. (1989). Toward phonetic intelligibility testing in dysarthria. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 54, 482–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laures J. S., & Weismer G. (1999). The effects of a flattened fundamental frequency on intelligibility at the sentence level. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 42, 1148–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss J. (2007). The role of speech perception in motor speech disorders. In Weismer G. (Ed.), Motor speech disorders (pp. 187–219). San Diego, CA: Plural. [Google Scholar]

- Logemann J. A., Fisher H. B., Boshes B., & Blonsky E. R. (1978). Frequency and cooccurrence of vocal tract dysfunctions in the speech of a large sample of Parkinson patients. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 43, 47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowit A., Dobinson C., Timmins C., Howell P., & Kröger B. (2010). The effectiveness of traditional methods and altered auditory feedback in improving speech rate and intelligibility in speakers with Parkinson's disease. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 12, 426–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow C. L., & Bassich C. J. (1984). Relationships between perceptual ratings and acoustic measures of hypokinetic speech. In McNeil M. R., Rosenbek J. C., & Aronson A. E. (Eds.), The dysarthrias: Physiology, acoustics, perception, management (pp. 163–195). San Diego, CA: College-Hill Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson M. K., Huber J. E., & Snow D. P. (2011). The intonation-syntax interface in the speech of individuals with Parkinson's disease. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 54, 19–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzner G. S., & Hillman R. E. (2005). Impact of aberrant acoustic properties on the perception of sound quality in electrolarynx speech. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48, 766–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metter J. E., & Hanson W. R. (1986). Clinical and acoustical variability in hypokinetic dysarthria. Journal of Communication Disorders, 19, 347–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz D. E., Schiavetti N., & Sacco P. R. (1990). Acoustic and psychophysical dimensions of the perceived speech naturalness of nonstutterers and posttreatment stutterers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 55, 516–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller N., Noble E., Jones D., Allcock L., & Burn D. J. (2008). How do I sound to me? Perceived changes in communication in Parkinson's disease. Clinical Rehabilitation, 22, 14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller N., Noble E., Jones D., & Burn D. (2006). Life with communication changes in Parkinson's disease. Age and Ageing, 35, 235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagle K. F., & Eadie T. L. (2012). Listener effort for highly intelligible tracheoesophageal speech. Journal of Communication Disorders, 45, 235–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel R., Connaghan K. P., & Campellone P. J. (2013). The effect of rate reduction on signaling prosodic contrasts in dysarthria. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 65, 109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pell M. D., Cheang H. S., & Leonard C. L. (2006). The impact of Parkinson's disease on vocal-prosodic communication from the perspective of listeners. Brain and Language, 97, 123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitcairn T. K., Clemie S., Gray J. M., & Pentland B. (1990). Impressions of Parkinsonian patients from their recorded voices. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 25, 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plowman-Prine E. K., Okun M. S., Sapienza C. M., Shrivastav R., Fernandez H. H., Foote K. D., … Rosenbek J. C. (2009). Perceptual characteristics of Parkinsonian speech: A comparison of the pharmacological effects of levodopa across speech and non-speech motor systems. NeuroRehabilitation, 24, 131–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramig L. O., Bonitati C., Lemke J., & Horii Y. (1994). Voice treatment for patients with Parkinson disease: Development of an approach and preliminary efficacy data. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 2, 191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Ramig L. O., Countryman S., Thompson L. L., & Horii Y. (1995). Comparison of two forms of intensive speech treatment for Parkinson disease. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 38, 1232–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramig L. O., Fox C., & Sapir S. (2004). Parkinson's disease: Speech and voice disorders and their treatment with the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment. Seminars in Speech and Language, 25, 169–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramig L. O., Fox C., & Sapir S. (2008). Speech treatment for Parkinson's disease. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 8, 297–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramig L. O., Sapir S., Countryman S., Pawlas A., O'Brien C., Hoehn M., & Thompson L. (2001). Intensive voice treatment (LSVT®) for patients with Parkinson's disease: A 2 year follow up. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, & Psychiatry, 71, 493–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubow R., & Swift E. (1985). A microcomputer-based wearable biofeedback device to improve transfer of treatment in Parkinsonian dysarthria. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 50, 178–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapir S., Spielman J. L., Ramig L. O., Story B. H., & Fox C. (2007). Effects of intensive voice treatment (the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment [LSVT]) on vowel articulation in dysarthric individuals with idiopathic Parkinson disease: Acoustic and perceptual findings. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50, 899–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott S., & Caird F. (1983). Speech therapy for Parkinson's disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, & Psychiatry, 46, 140–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodda S., Grönheit W., & Schlegel U. (2011). Intonation and speech rate in Parkinson's disease: General and dynamic aspects and responsiveness to levodopa admission. Journal of Voice, 25, e199–e205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodda S., Rinsche H., & Schlegel U. (2009). Progression of dysprosody in Parkinson's disease over time: A longitudinal study. Movement Disorders, 24, 716–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwood M., & Weismer G. (1993). Listener judgments of the bizarreness, acceptability, naturalness, and normalcy of the dysarthria associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 1, 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Spielman J., Ramig L. O., Mahler L., Halpern A., & Gavin W. J. (2007). Effects of an extended version of the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment on voice and speech in Parkinson's disease. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16, 95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulos E. T., Huber J. E., Richardson K., Kamphaus J., DeCicco D., Darling M., … Sussman J. E. (2014). Increased vocal intensity due to the Lombard effect in speakers with Parkinson's disease: Simultaneous laryngeal and respiratory strategies. Journal of Communication Disorders, 48, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teshima S., Langevin M., Hagler P., & Kully D. (2010). Post-treatment speech naturalness of Comprehensive Stuttering Program clients and differences in ratings among listener groups. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 35, 44–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden K., & Wilding G. E. (2004). Rate and loudness manipulations in dysarthria: Acoustic and perceptual findings. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 47, 766–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trail M., Fox C., Ramig L. O., Sapir S., Howard J., & Lai E. C. (2005). Speech treatment for Parkinson's disease. NeuroRehabilitation, 20, 205–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weismer G., & Laures J. S. (2002). Direct magnitude estimates of speech intelligibility in dysarthria: Effects of a chosen standard. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 45, 421–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehill T., Ciocca V., & Yiu E. (2004). Perceptual and acoustic predictors of intelligibility and acceptability in Cantonese speakers with dysarthria. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 12, 229–233. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2006). Neurological disorders: Public health challenges. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Yorkston K. M., Beukelman D. R., Strand E. A., & Bell K. (1999). Management of motor speech disorders in children and adults (2nd ed.). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Yorkston K. M., Miller R., & Strand E. (2004). Management of speech and swallowing in degenerative diseases (2nd ed.). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. [Google Scholar]