Abstract

Background:

Nonoccupational anthracosis and silicosis has been reported from various parts of the world including Ladakh in Jammu and Kashmir, India; however, anthracosilicosis has only been reported in industrial workers till date.

Materials and Methods:

Six cases from the Ladakh region in Jammu and Kashmir, India with similar clinico-radiological-pathological features, i.e., anthracosilicosis/anthracofibrosis have been analyzed. Of these, four were analyzed retrospectively and two prospectively.

Result:

All the patients were homemakers and resided in Ladakh in Jammu and Kashmir, India since birth with an age range of 42–62 years and an average age of 56 years. Their average duration of symptoms was 4 years. Spirometry showed small and/or large airway disease in 5/6 cases. On computed tomography (CT), 4/6 cases showed progressive massive fibrosis (PMF) with calcified mediastinal lymph nodes. There were random or centrilobular nodules in all the six cases. Bronchoscopy in 5/6 cases showed multiple anthracotic pigments with narrowing and distortion of the bronchus (anthracofibrosis). Malignancy was suspected clinico-radiologically in four cases and pathologically in two cases. On histopathology, anthracosis was demonstrated in all and silicosis in three cases.

Conclusion:

Anthracosilicosis can occur due to environmental exposure. Ladakh in Jammu and Kashmir, India is the only place across the globe with unique environmental features having the presence of both free silica and biomass fuel. The disease was observed predominantly in older women. Awareness would prevent unnecessary investigation for malignancy. Treatment with the bronchodilator is useful as it has evidence of airway disease. Finally, environmental measures and a proper study need to be undertaken for knowing the relative role of silica versus soot in causing the lung disease and preventing this irreversible condition.

Keywords: Anthracofibrosis, anthracosilicosis, anthracosis, environmental, nonoccupational

INTRODUCTION

The term “Pneumoconiosis” was coined by Zenker to define a group of diseases caused by inhalation of dust. The most common pneumoconiosis are silicosis, coal workers' pneumoconiosis, and asbestosis.[1] Silicosis is a fibrosing disease of the lung caused by the inhalation, retention, and pulmonary reaction to crystalline silica.[2] Silicosis is known to cause random nodules, progressive massive fibrosis (PMF), and obstructive airway disease.[2] Anthracosis or coal workers' pneumoconiosis is seen in coal workers and is caused by inhalation and deposition of black pigments of which carbon is a major constituent.[3,4] Air pollution, biomass smoke, and cigarette smoke are also known to cause deposition of black pigment leading to environmental anthracosis. Environmental anthracosis usually leads to anthracofibrosis (anthracosis with bronchial narrowing) and obstructive airway disease. It is not known to cause PMF. Both anthracosis and silicosis have been reported due to nonoccupational cause.[5,6] But anthracosilicosis, a form of mixed dust pneumoconiosis, has not been reported due to nonoccupational cause. We present six cases of nonoccupational anthracofibrosis/anthcosilicosis from Ladakh in Jammu and Kashmir, India.

CASE REPORTS

Six cases from the Ladakh region in Jammu and Kashmir (India) that presented to a tertiary care institute in Delhi from January 2012 to July 2015 with similar clinico-radiological-pathological features were analyzed. Of these six cases, four were analyzed from the available records and two were analyzed prospectively. The ethics committee was notified about these cases. These cases are described below and have been summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of patients

Case 1

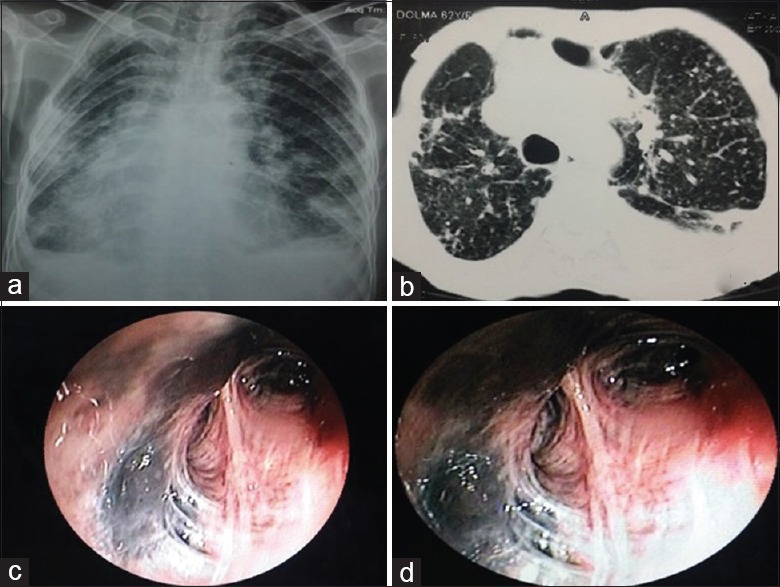

A 58-year-old nonsmoker lady had presented with breathlessness on exertion and cough with melanoptysis for 5 years. There was no significant past history except having taken antitubercular therapy 3 years ago for the same complaints with no improvement in the symptoms. On examination, the vital parameters were normal. There were bilateral fine crackles and occasional rhonchi on the respiratory system examination. The routine biochemical and hematological investigations were normal. The chest radiograph is shown in Figure 1a. The available computed tomography (CT) of the chest showed partially calcified bilateral uppers lobe masses, air trapping, and random nodules all over the lung fields [Figure 1b–d]. CT of the chest performed 2 years ago was also available in the records. On comparison of two CT scans, the masses had increased by 7 mm on the right side and 6 mm on the left side. The spirometry showed forced vital capacity (FVC) of 1.43 lit (67% predicted), forced expiratory volume in the 1st second (FEV1) of 1.10 lit (62% predicted) with FEV1/FVC of 0.77. Bronchoscopy had shown narrowing of both the upper lobe bronchi and distortion of the bronchial tree with deposition of anthracotic pigments throughout the bronchial tree [Figure 2a–c]. Transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) showed nodular aggregates of polygonal cells with abundant black pigment in the cytoplasm. The nuclei of these cells showed mild atypia with no evidence of mitotic figures. There was a suspicion of melanoma; hence, immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed. IHC was positive for CD68 while negative for CD56, HMB-45, and Ki, and hence, melanoma was ruled out. Transthoracic trucut biopsy was consistent with anthracosis [Figure 2d]. A final diagnosis of anthracofibrosis was made, as polarized light microscopy, which is pathognomonic of silicosis had not been performed in this case.

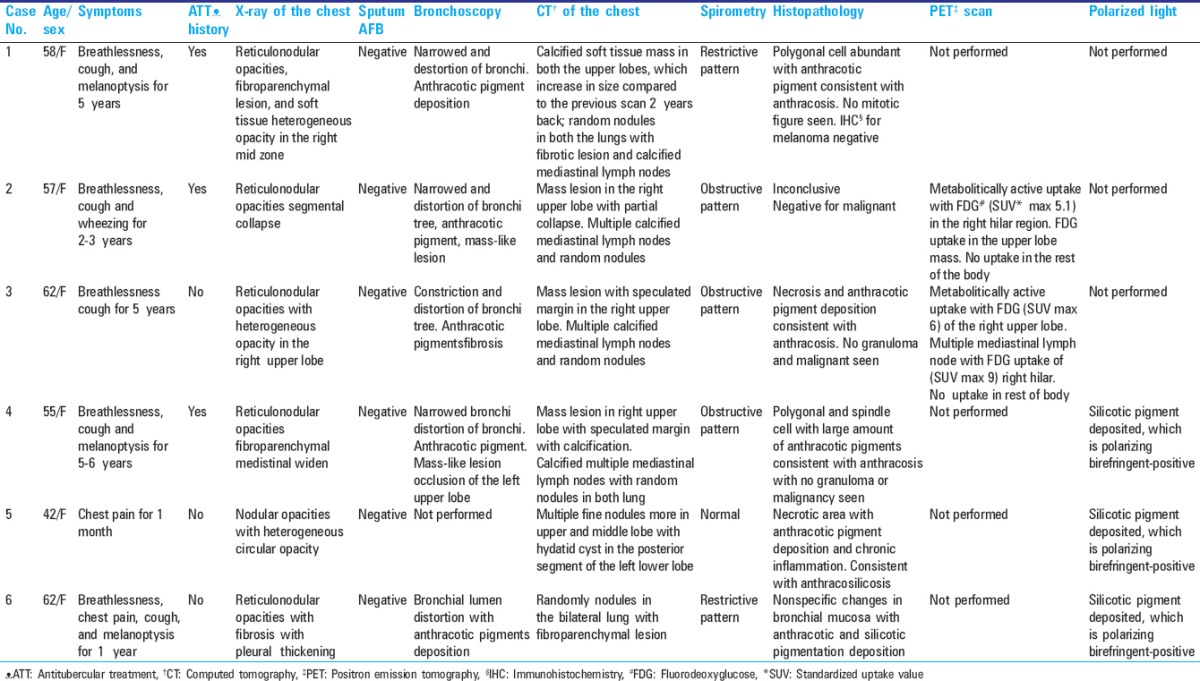

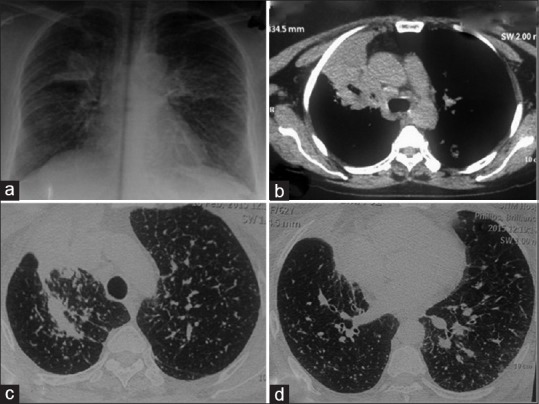

Figure 1.

(Case 1): a) Chest radiograph showing bilateral reticulonodular opacities, upper lobe fibroparenchymal lesion and heterogenous opacity in left mid zone. b) CT chest showing partially calcified soft tissue mass in the right upper lobe 34×58mm (shown by arrow) and left upper lobe (35×51mm). c) Fibrotic changes seen in both upper lobes d) Randomly distributed nodules in bilateral lung

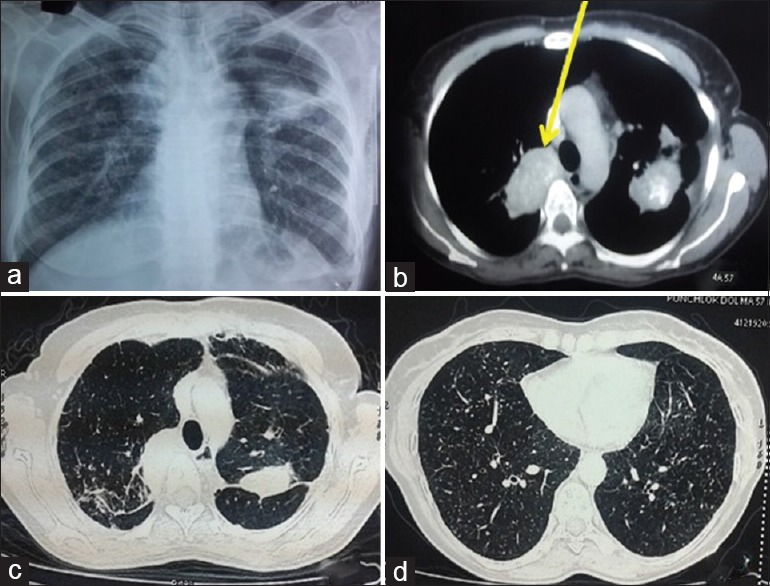

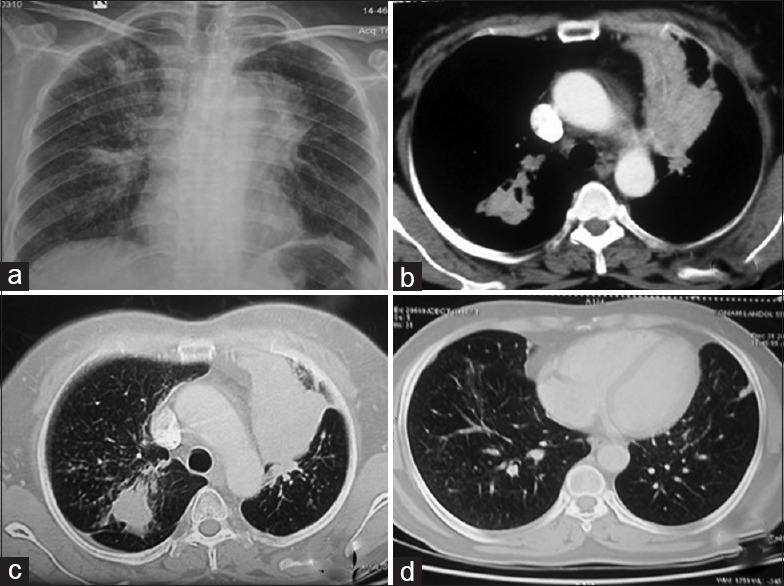

Figure 2.

(Case 1): (a and c) Bronchoscopy showing deposition of anthracotic pigments thought out bronchial tree on both sides and narrowing upper lobe bronchi due to b) external compression with distortion of bronchial lumen. d) Biopsy showing aggregates of polygonal cells with abundant black pigment in cytoplasm. Stroma was made up of fibrocollagenous tissue with neutrophils and mononuclear cells consistent diagnosis of anthracosis

Case 2

A 57-year-old nonsmoker lady from Ladakh in Jammu and Kashmir, India had presented with breathlessness on exertion and minimal cough for 2–3 years with occasional history of wheezing. There was also history of antitubercular treatment 9–10 years ago for 9 months. On examination, the vital parameters were within normal limits. There were scattered rhonchi on respiratory system examination. The chest radiograph showed reticulonodular opacities with right upper lobe collapse [Figure 3a]. The CT showed an ill-defined mass-like lesion in the right hilum with air trapping and multiple random nodules scattered in both the lung fields [Figure 3b–d]. The spirometry showed FVC of 2.36 lit (105% predicted), FEV1 of 0.99 lit (53% predicted), FEV1/FVC - 0.42. The DLCO was 1.26 mL/kg/min (76% predicted). The bronchoscopy had shown anthracotic pigment over the trachea. Both the right and left bronchial anatomies were distorted, with mucosal edema and anthracotic pigment. The right upper lobe lumen was not visualized. The bronchoscope could not be negotiated into the right intermedius bronchus due to distorted anatomy. No endobronchial growth was seen. Bronchial biopsy was taken from the right side. It showed bits of bronchial mucosa lined with metaplastic squamous epithelium. No malignant cell was seen. A repeat biopsy to rule out malignancy was taken but it showed a similar pathology. Whole body positron emission tomography (PET)-CT scan showed confluent lymph nodes with increased fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the right hilum [Table 1]. As per the records, she was being followed up for 2 years and treated with inhaled bronchodilator. The spirometry had shown improvement in FVC by 760 mL and FEV1 by 720 mL. After 2 years a repeat bronchoscopy, CT scan chest, and PET scan had also been performed. There was no significant change in CT scan, bronchoscopy, and PET scan compared to previous reports. A diagnosis of anthracofibrosis was made on the basis of nonprogressive lesions, bronchoscopy, and histopathology. Polarized light microscopy was not performed in this case.

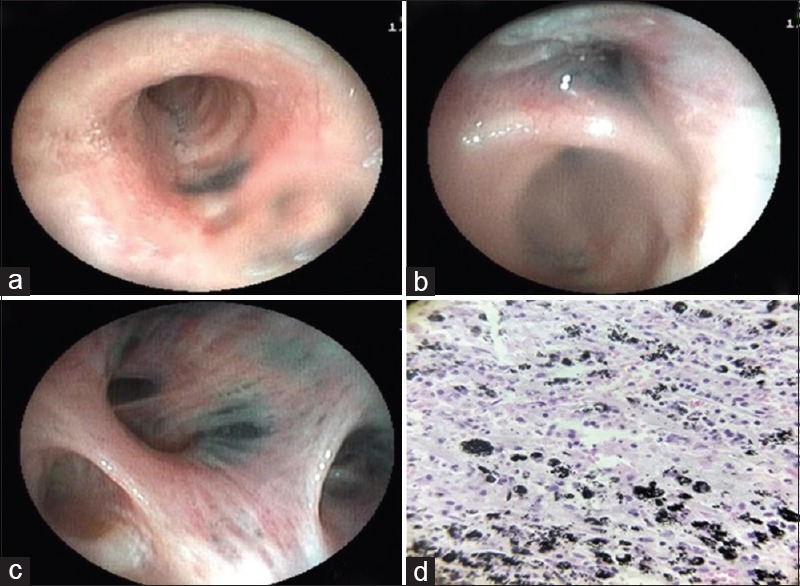

Figure 3.

(Case 2): a) Chest radiograph showing reticulo-nodular opacities in bilateral lung with segmental collapse of right upper lobe. b) CT chest showing ill-defined mass lesion of (3.2×2.7cm) in right hilum encasing the right upper lobe bronchus causing an abrupt cut off. c) Partial collapse of right upper lobe. d) Multiple randomly distributed nodules scatted in both lungs

Case 3

A 62-year-old old nonsmoker lady had presented with breathlessness on exertion of 5 years and cough with minimum sputum for 2–3 years. On examination, the vitals were within normal limits. There were scattered rhonchi on respiratory system examination. The chest radiograph is shown in Figure 4a. The CT had shown speculated mass lesion in the apical segments of the right upper lobe with air trapping and random nodules [Figure 4b–d]. The spirometry had shown FVC of 1.99 lit (84% predicted), FEV1 of 1.35 lit (69% predicted) with FEV1/FVC of 0.68. Bronchoscopy had shown constriction and deposition of anthracotic pigments in the right upper lobe bronchus. Secondary carina on the left side was widened with anthracotic pigments. Left upper lobe bronchus was constricted due to fibrosis. The bronchial biopsy was inconclusive. Whole body PET-CT scan showed an increased FDG uptake in the lung lesions and lymph nodes. Transthoracic lung biopsy of the lung mass was performed, which showed necrosis and anthrocotic pigment deposition consistent with anthracofibrosis. The sample was not subjected to polarized light and hence, a final diagnosis of anthracofibrosis was made.

Figure 4.

(Case 3): a) Chest radiograph showing bilateral small nodular opacities in all zones with one heteogenous opacity in right upper lobe. b) CT chest showing speculated mass in right upper lobe. (c and d) Multiple randomly distributed nodules scatted in bilateral lung field

Case 4

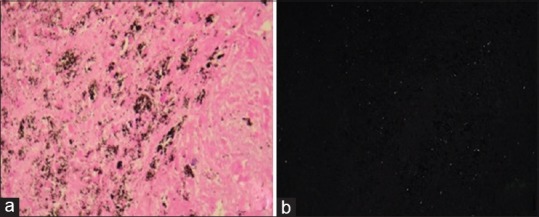

A 55-year-old nonsmoker lady had presented with dyspnea on exertion and cough with melanoptysis for the last 5–6 years. There was history of bronchodilator therapy for 3 years with some improvement in the symptoms. On examination, the vital parameters were within normal limits. There were bilateral fine crackles and occasional rhonchi on respiratory system examination. The routine biochemical and hematological investigations were normal. The chest radiograph is shown in Figure 5a. The CT of the chest showed an irregular soft tissue mass in both the upper lobes with random nodules in both the lungs [Figure 5b–d]. The spirometry showed FVC of 2.75 lit (131% predicted), FEV1 of 1.49 lit (85% predicted), and FEV1/FVC of 0.54. The diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) was -1.73 mL/kg/min (102% predicted). Bronchoscopy showed extensive anthracotic pigments scattered throughout the bronchial tree with complete occlusion of the left upper division with mass-like lesion [Figure 6a and b]. Bronchial biopsy was inconclusive; hence, trucut transthoracic lung biopsy was performed, which showed a tumor of polygonal and spindle cells. A suspicion of malignant melanoma was raised due to heavy pigmentation. Review of the biopsy from another pathologist did not confirm melanoma. Hence, a repeat biopsy was performed, which showed features of anthracosis [Figure 6c] and deposition of silicotic pigment (polarizing birefringent-positive) [Figure 6d]. A diagnosis of anthracosilicosis was made.

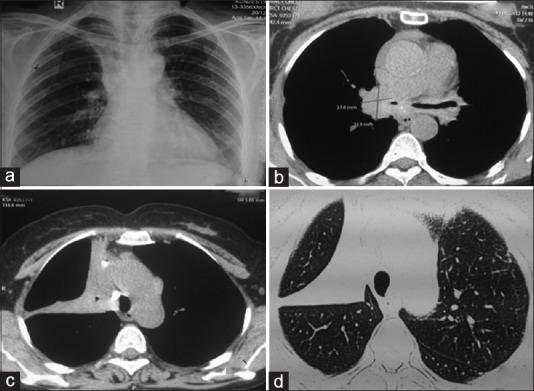

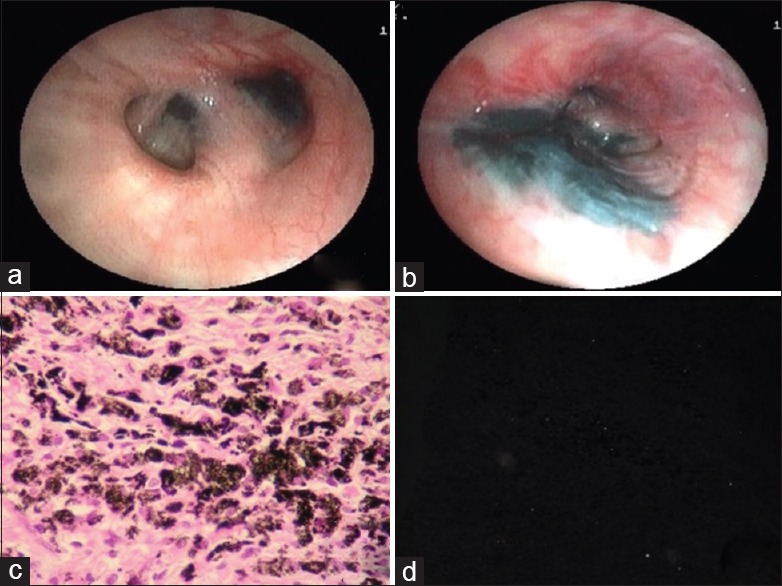

Figure 5.

(Case 4): a) Chest radiograph showing reticulo-nodular opacities in bilateral lung with fibrotic lesion on right parahilar region with mediastinal widening. b) CT chest showing irregular soft tissue (3 × 2.8 × 2.6 cm) mass with speculated margin, calcification and collapse of left upper lobe. c) Fibrotic changes in right upper. d) Multiple tiny random nodules were scattered in both lungs

Figure 6.

(Case 4): a) Bronchoscopy showing extensive anthracotic pigments deposition throughout the bronchial tree of both sides (a) with complete occlusion of left upper division with mass like lesion and b) distortion of bronchial lumen. c) Biopsy showing alveolar septae thicken due to infiltration of numerous polygonal and spindle cell with large amount of black (anthracotic) pigment. There were chronic inflammatory cells, pigment-laden macrophages, and fibrosis. d) The fibrous tissue was heavily infiltrated with silicotic pigment deposition (polarizing birefregent positive)

Case 5

A 42-year-old nonsmoker lady was investigated by the local physician with chest radiograph, CT scan of the thorax, and other routine investigation, and diagnosed to have left lower lobe hydatid cyst. She was referred for operative management. On examination, the vital parameters were within normal limits. The respiratory system examination was unremarkable. The chest radiograph is shown in Figure 7a. The CT showed diffuse fine nodules in both the lung fields, with a left lower lobe hydatid cyst [Figure 7b–d]. The spirometry showed FVC of 2.94 lit (105% predicted), FEV1 of 2.33 lit (93% predicted) with FEV1/FVC 0.76. The DLCO was 5.63 mL/kg/min (104% predicted). She was treated with oral albendazole 10 mg/kg per day and planned for surgery of hydatid cyst. Video-assisted thoracoscopy with excision of the hydatid cyst was performed and simultaneous biopsy was taken from the lung parenchyma. Apart from hydatid cyst, the lung biopsy showed anthracotic and polarizing birefringent pigment deposition [Figure 8a and b], suggestive of anthracosilicosis.

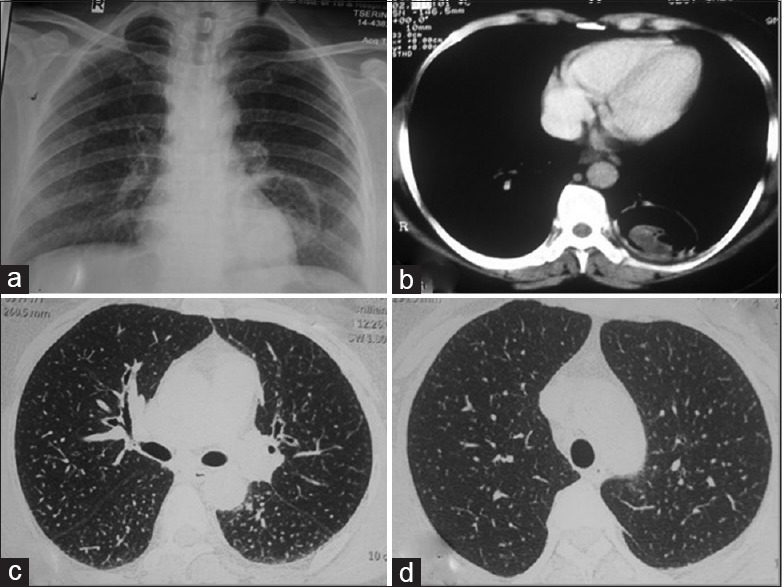

Figure 7.

(Case 5): a) Chest radiograph showing bilateral small nodular opacities in all zones with well, defined circular heterogeneous opacity in left lower lobe para and retrocardiac region. CECT chest showing b) well defined cavity containing soft tissue density in posterior basal segment of left lower lobe and (c and d) randomly distributed fine nodules involving bilateral lung parenchyma

Figure 8.

(Case 5): a) Lung biopsy showing fibrous exudate, macular patches around the bronchovascular bundle, circumscribed necrotic area with anthracotic and b) polarizing birefregent pigment deposition

Case 6

A 62-year-old nonsmoker lady presented with breathlessness on exertion, chest pain, and cough with on-and-off melanoptysis for 1 year. On examination, the vitals were within normal limits. There were scattered rhonchi with crepitation on respiratory system examination. The chest radiograph is shown in Figure 9a. The CT showed multiple centrilobular nodules scattered in both the lungs with fibroparenchymal changes and air trapping [Figure 9b]. The spirometry showed FVC of 1.54 lit (63% predicted), FEV1 of 1.22 lit (60% predicted) with FEV1/FVC of 0.79. Bronchoscopy showed anthrocotic pigments deposition in both sides with distortion of the bronchial mucosa [Figure 9c and d]. Bronchial biopsy showed nonspecific changes in the bronchial mucosa with anthracotic and silicotic pigment depositions. Polarizing birefringent was positive. A diagnosis of anthracosilicosis was made.

Figure 9.

(Case 6): a) Chest radiograph showing bilateral small nodular opacities in all zones with fibroparenchymal changes with pleural thickening. b) CECT chest showing randomly distributed nodules scatted in bilateral lung fields with fibroparenchymal changes and pleural reaction. (c and d) Bronchoscopy showing anthracotic pigments deposition throughout bronchial tree of both sides with luminal distortion

DISCUSSION

Anthracosis and silicosis are observed both in industrial workers and the nonindustrial population.[4,5,7,8,9,10,11] But anthracosilicosis has only been reported in industrial workers.[12] We have described six cases of nonoccupational anthracofibrosis/anthracosilicosis from the Ladakh region of Jammu and Kashmir in North India. Nonoccupational silicosis has been reported from various parts of the world including Ladakh.[6,12,13,14] In the study from Ladakh, the presence of soot and silica was demonstrated in the environment of Ladakh but the radiographic abnormality in the study was attributed to only silica. In fact, anthracosis and anthracofibrosis have been described from many parts of the country[10,11,15] but not from Ladakh. Also, this is the first time that anthracosilicosis has been described in the nonindustrial population. In our study, we could demonstrate soot in 6/6 cases and both soot and silica in the pathological samples of only 3/6 cases. These three patients where silica was not demonstrated were analyzed retrospectively. However, we believe that all the patients had anthracosilicosis because there is high predilection of silica exposure in the Ladakh region in Jammu and Kashmir, India (discussed later). Also, these three cases where silica could not be demonstrated had PMF with random nodules, a finding common with silica dust but not with anthracofibrosis.

Ladakh in Jammu and Kashmir, India is among the highest of the world's inhabited plateaus situated at >10,000 feet above the sea level. This high altitude and geographic location of Ladakh gives rise to the long duration of winter of nearly 4–5 months in years with sub-zero temperature.[16] One of the reasons for anthracosilicosis may be exposure to soot from the burning of wood and dung in winter to keep the rooms warm. Houses in Ladakh have fireplaces in the center of room, which use partially burnt wood/dung with smoke during the noncooking period. People usually remain indoors during this prolonged harsh winter; cooking is also usually done in the same room [Figure 10a]. The windows are also very small and the houses lack chimneys [Figure 10b]. These practices expose the residents to high concentrations of soot. Women are exposed more to this smoke and soot compared to men because of cooking and indoor confinement.[6] All the six cases in our series were women. The other reason for anthracosilicosis is exposure to silica dust. Dust storm is common in Ladakh mostly during spring season. During these storms a thick blanket of fine dust covers the affected villages, and inhabitants are exposed to considerable amounts of the dust for several days.[5] The frequency, duration, and severity of these dust storms vary considerably from one village to another. In a study by Norboo et al., dust taken from the living rooms from one of the village's houses had particles ranging from 0.5–5 µm diameters and about half of it was silica.[6] Women are again more prone to exposure because they do most of the farming work, sweep the dusty houses, and carry baskets of earth for the traditional toilets. These unique environmental features make the population in Ladakh, especially women, prone to nonoccupational anthracosilicosis.

Figure 10.

a) Roof and wall of the living room showing deposition of black soots and smoke particles. b) Showing old type of chula without chimney use decade back. c) New type of chula with chimmey using presently and old one

Nobroo et al. had mentioned about taking preventive measures in their study. In the last 30 years, a few preventive measures have been taken, i.e. some of the villages have switched over to electrical heating measures and chimneys have been installed in certain houses in the towns and cities [Figure 10c]. However, preventive measures are still required. These are: Awareness about environmental hygiene, education about installation of chimneys and exhaust fans in all the villages, and using noncombustive substance for cooking and heating in remote areas as well. A systemic study also needs to be undertaken in order to find out the exact role of silica and soot each and prevent this irreversible disease.

On CT 4/6 cases showed mass lesions of >3 cm size, i.e., PMF with calcified mediastinal lymph nodes, which is one of the commonest lesions seen in complicated pneumoconiosis.[17] In two of the cases (cases 1 and 4), an increase in the size of the mass lesion was demonstrated. PET scan of two of the patients (cases 2 and 3) showed an increased FDG uptake as well. In two of the cases, even histopathology mimicked malignancy (cases 1 and 4). Although increase in the size of the lesion, increased metabolic uptake and anthracotic pigments are known to occur in PMF,[18] these findings can be mistaken for malignancy if the patient is not expected to have PMF. There were random nodules and centrilobular nodules in all the six cases, which might have been misdiagnosed as miliary or pulmonary tuberculosis. In this series, three out of six patients (cases 1, 2, and 4) had received antituberculosis treatment possibly erroneously. Increased awareness about environmental anthracosilicosis can be helpful in preventing erroneous diagnosis of tuberculosis as well as malignancy.

Clinical finding, CT scan, and/or spirometry showed obstructive airway disease in all cases except for case 5 possibly because she was diagnosed incidentally early in the course of illness while undergoing investigation for hydatid. She was more than a decade younger than her counterparts. She would have had a similar fate after a few years, had she not been diagnosed and advocated the preventive measures. The obstructive abnormalities in other cases were possibly due to both soot and silica since both are known to cause obstructive airway disease.[19] Silica leads to obstructive airway disease because of inflammation of large and small airways with emphysema,[20] whereas anthracosis leads to chronic bronchitis.[21] The treatment of airway disease in these patients would go a long way in treating this “untreatable” disease.

On bronchoscopy, five cases showed multiple anthracotic pigments with narrowing and distortion of the bronchus, which is pathognomonic of anthracofibrosis.[3,4,22] On histopathology, abundant black anthracotic pigment was present in all the cases that was suggestive of anthracosis. The presence of birefringent particles on polarized light microscopy, which is diagnostic of silicosis is essential when the role of environmental dust is not known.[2,23,24] The earlier study reported from Ladakh in Jammu and Kashmir, India did not correlate the environmental dust with pathological findings.[25] We could demonstrate silicosis in only 3/6 cases because of retrospective analysis. So, though we have not accurately completed the unfinished work of Sayeed et al., it is an important step for inciting a prospective research in order to improve the environmental anomaly of this region.

CONCLUSION

Anthracosilicosis is a common finding among older female Ladakh residents due to exposure to free silica and biomass fuel smoke in the environment. The residents and treating physicians need to be aware about this nonoccupational risk. Awareness would prevent unnecessary investigation for malignancy and treatment with antituberculosis drugs. Treatment with bronchodilator is important for these “nontreatable'” patients. Finally, environmental measures and a proper study need to be undertaken for knowing a relative role of silica versus soot in causing the lung disease and preventing this irreversible condition.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Parveen Nath and Dr. Mohd Shamim for helping in the workup of the patients.

REFERENCES

- 1.Seaton A. Occupational lung diseases. In: Seaton A, editor. Chroftan and Doughlas's Text Book of Respiratory Diseases. 5th ed. France: Blackwell Science; 2009. p. 1408. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petsonk EL, Parker JE. Coal workers' lung disease and silicosis. In: Fishman AP, editor. Fishman's Textbook of Pulmonary Disease and Disorders. New York: McGraw Hill Medicine; 2008. pp. 974–75. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Comert SS, Dogan C, Caglayan B, Fidan A, Kiral N, Salepci B. The demographic, clinical, radiographic and bronchoscopic evaluation of anthracosis and anthracofibrosis cases. J Pulmonar Respir Med. 2012;2:119. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung MP, Lee KS, Han J, Kim H, Rhee CH, Han YC, et al. Bronchial stenosis due to anthracofibrosis. Chest. 1988;113:344–50. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norboo T, Angchuck PT, Yahya M, Kamat SR, Pooley FD, Corrin B, et al. Silicosis in a Himalayan village population: Role of environmental dust. Thorax. 1991;46:341–3. doi: 10.1136/thx.46.5.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saiyed HN, Sharma YK, Sadhu HG, Norboo T, Patel PD, Patel TS, et al. Non-occupational pneumoconiosis at high altitude villages in central Ladakh. Br J Ind Med. 1991;48:825–9. doi: 10.1136/oem.48.12.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirsadraee M, Saeedi P. Anthracosis of the Lung: Evaluation of potential causes. Iran J Med Sci. 2005;30:190–3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta A, Shah A. Bronchial anthracofibrosis: An emerging pulmonary disease due to biomass fuel exposure. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:602–12. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh V, Meena H, Bairwa R, Singh S, Sharma BB, Singh A. Clinico-radiological profile and risk factors in patients with anthracosis. Lung India. 2015;32:102–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.152614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sigari N, Mohammadi S. Anthracosis and anthracofibrosis. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:1063–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Törün T, Güngör G, Özmen I, Maden E, Bölükbaşı Y, Tahaoğlu K. Bronchial anthracostenosis in patients exposed to biomass smoke. Turk Respir J. 2007;8:48–51. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Policard A, Collet A. Deposition of silicosis dust in the lungs of the inhabitants of the Sahara regions. AMA Arch Ind Hyg Occup Med. 1952;5:527–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fennerty A, Hunter AM, Smith AP, Pooley FD. Silicosis in a Pakistani farmer. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;287:648–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.287.6393.648-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawass ND. Non-occupational pneumoconiosis (desert lung) In: Capesius P, editor. Proceedings of 15th International Congress of Radiology. Chest and Breast. Luxembourg: Interimages; 1983. pp. 280–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waldermar CD, Jones RR. Anthracosilicosis. JAMA. 1936;107:1179–85. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janet R. Ladakh - Crossroads of High Asia. 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 117–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferreira AS, Moreira VB, Ricado HM, Coutinho R, Gabetto JM, Marchiori E. Progressive massive fibrosis in silica-exposed workers. High-resolution computed tomography findings. J Bras Pneumol. 2006;32:523–8. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132006000600009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung SY, Lee JH, Kim TH, Kim SJ, Kim HJ, Ryu YH. 18 F-FDG PET imaging of progressive massive fibrosis. Ann Nucl Med. 2010;24:21–7. doi: 10.1007/s12149-009-0322-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeoh CI, Yang SC. Pulmonary function impairment in pneumoconiotic patients with progressive massive fibrosis. Chang Gung Med J. 2002;25:72–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hnizdo E, Vallyathan V. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease due to occupational exposure to silica dust: A review of epidemiological and pathological evidence. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:237–43. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.4.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mirsadraee M, Asnaashar M, Attaran D. Pattern of pulmonary function test abnormalities in anthracofibrosis of the lungs. Tanaffos. 2012;11:34–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wynn GJ, Turkington PM, O'Driscoll BR. Anthracofibrosis, bronchial stenosis with overlying anthracotic mucosa: Possibly a new occupational lung disorder: A series of seven cases from one UK hospital. Chest. 2008;134:1069–73. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonald JW, Roggli VL. Detection of silica particles in lung tissue by polarizing light microscopy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:242–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldsmith S, Kopeloff A. Use of polarized-light microscopy as an aid in the diagnosis of silicosis. N Engl J Med. 1961;265:233–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196108032650507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franco G, Massola A. Non-occupational pneumoconiosis at high altitude villages in central Ladakh. Br J Ind Med. 1992;49:452–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]